2

Professional communication in written form requires skill and expertise. From text messages to reports, how you represent yourself with the written word counts. Writing in an online environment requires tact, skill, and an awareness that what you write may be there forever. From memos to letters, from business proposals to press releases, your written business communication represents you and your company: your goal is to make it clear, concise, and professional.

Text, e-mail, and netiquette

Text messages and e-mails are part of our communication landscape, and skilled business communicators consider them a valuable tool to connect. Netiquette refers to etiquette, or protocols and norms for communication, on the Internet.

Texting

Whatever digital device you use, written communication in the form of brief messages, or texting, has become a common way to connect. It is useful for short exchanges, and is a convenient way to stay connected with others when talking on the phone would be cumbersome. Texting is not useful for long or complicated messages, and careful consideration should be given to the audience. Although texting will not be used in this class as a form of professional communication, you should be aware of several of the principles that should guide your writing in this context.

When texting, always consider your audience and your company, and choose words, terms, or abbreviations that will deliver your message appropriately and effectively.

Tips for effective business texting

- Know your recipient; “? % dsct” may be an understandable way to ask a close associate what the proper discount is to offer a certain customer, but if you are writing a text to your boss, it might be wiser to write, “what % discount does Murray get on $1K order?”

- Anticipate unintentional misinterpretation. Texting often uses symbols and codes to represent thoughts, ideas, and emotions. Given the complexity of communication, and the useful but limited tool of texting, be aware of its limitation and prevent misinterpretation with brief messages.

- Contacting someone too frequently can border on harassment. Texting is a tool. Use it when appropriate but don’t abuse it.

- Don’t text and drive. Research shows that the likelihood of an accident increases dramatically if the driver is texting behind the wheel. [1] Being in an accident while conducting company business would reflect poorly on your judgment as well as on your employer.

E-mail is familiar to most students and workers. It may be used like text, or synchronous chat, and it can be delivered to a cell phone. In business, it has largely replaced print hard copy letters for external (outside the company) correspondence, and in many cases, it has taken the place of memos for internal (within the company) communication.[2] E-mail can be very useful for messages that have slightly more content than a text message, but it is still best used for fairly brief messages. Many businesses use automated e-mails to acknowledge communications from the public, or to remind associates that periodic reports or payments are due. You may also be assigned to “populate” a form e-mail in which standard paragraphs are used but you choose from a menu of sentences to make the wording suitable for a particular transaction.

E-mails may be informal in personal contexts, but business communication requires attention to detail, awareness that your e-mail reflects you and your company, and a professional tone so that it may be forwarded to any third party if needed. E-mail often serves to exchange information within organizations. Although e-mail may have an informal feel, remember that when used for business, it needs to convey professionalism and respect. Never write or send anything that you wouldn’t want read in public or in front of your company president.

Tips for effective business e-mails

As with all writing, professional communications require attention to the specific writing context, and it may surprise you that even elements of form can indicate a writer’s strong understanding of audience and purpose. The principles explained here apply to the educational context as well; use them when communicating with your instructors and classroom peers.

- Open with a proper salutation. Proper salutations demonstrate respect and avoid mix-ups in case a message is accidentally sent to the wrong recipient. For example, use a salutation like “Dear Ms. X” (external) or “Hi Barry” (internal).

- Include a clear, brief, and specific subject line. This helps the recipient understand the essence of the message. For example, “Proposal attached” or “Your question of 10/25.”

- Close with a signature. Identify yourself by creating a signature block that automatically contains your name and business contact information.

- Avoid abbreviations. An e-mail is not a text message, and the audience may not find your wit cause to ROTFLOL (roll on the floor laughing out loud).

- Be brief. Omit unnecessary words.

- Use a good format. Divide your message into brief paragraphs for ease of reading. A good e-mail should get to the point and conclude in three small paragraphs or less.

- Reread, revise, and review. Catch and correct spelling and grammar mistakes before you press “send.” It will take more time and effort to undo the problems caused by a hasty, poorly written e-mail than to get it right the first time.

- Reply promptly. Watch out for an emotional response—never reply in anger—but make a habit of replying to all e-mails within twenty-four hours, even if only to say that you will provide the requested information in forty-eight or seventy-two hours.

- Use “Reply All” sparingly. Do not send your reply to everyone who received the initial e-mail unless your message absolutely needs to be read by the entire group.

- Avoid using all caps. Capital letters are used on the Internet to communicate emphatic emotion or yelling and are considered rude.

- Test links. If you include a link, test it to make sure it is working.

- E-mail ahead of time if you are going to attach large files (audio and visual files are often quite large) to prevent exceeding the recipient’s mailbox limit or triggering the spam filter.

- Give feedback or follow up. If you don’t get a response in twenty-four hours, e-mail or call. Spam filters may have intercepted your message, so your recipient may never have received it.

Figure 1 shows a sample email that demonstrates the principles listed above.

Figure 1. Sample email

From: Steve Jobs <sjobs@apple.com> To: Human Resources Division <hr@apple.com> Date: September 12, 2015 Subject: Safe Zone Training Dear Colleagues: Please consider signing up for the next available Safe Zone workshop offered by the College. As you know, our department is working toward increasing the number of Safe Zone volunteers in our area, and I hope several of you may be available for the next workshop scheduled for Friday, October 9. For more information on the Safe Zone program, please visit http://www.cocc.edu/multicultural/safe-zone-training/ Please let me know if you will attend. Steve Jobs |

Netiquette

We create personal pages, post messages, and interact via online technologies as a normal part of our careers, but how we conduct ourselves can leave a lasting image, literally. The photograph you posted on your Facebook page or Twitter feed may have been seen by your potential employer, or that nasty remark in a post may come back to haunt you later.

Following several guidelines for online postings, as detailed below, can help you avoid embarrassment later.

Know your context

- Introduce yourself.

- Avoid assumptions about your readers. Remember that culture influences communication style and practices.

- Familiarize yourself with policies on Acceptable Use of IT Resources at your organization. (COCC’s acceptable use policy can be found here: http://www.cocc.edu/its/computer-labs/acceptable-use-of-information-technology-resources/ )

Remember the human

- Remember there is a person behind the words. Ask for clarification before making judgement.

- Check your tone before you publish.

- Respond to people using their names.

- Remember that culture and even gender can play a part in how people communicate.

- Remain authentic and expect the same of others.

- Remember that people may not reply immediately. People participate in different ways, some just by reading the communication rather than jumping into it.

- Avoid jokes and sarcasm; they often don’t translate well to the online environment.

Recognize that text is permanent

- Be judicious. What you say online is difficult to retract later.

- Consider your responsibility to the group and to the working environment.

- Agree on ground rules for text communication (formal or informal; seek clarification whenever needed, etc) if you are working collaboratively.

Avoid flaming: research before you react

- Accept and forgive mistakes.

- Consider your responsibility to the group and to the working environment.

- Seek clarification before reacting.

- Ask your supervisor for guidance.*

Respect privacy and original ideas

- Quote the original author if you are responding to a specific point made by someone else.

- Ask the author of an email for permission before forwarding the communication.

* Sometimes, online behavior can appear so disrespectful and even hostile that it requires attention and follow up. In this case, let your supervisor know right away so that the right resources

can be called upon

to help.

Memorandums and letters

Memos

A memo (or memorandum, meaning “reminder”) is normally used for communicating policies, procedures, or related official business within an organization. It is often written from a one-to-all perspective (like mass communication), broadcasting a message to an audience, rather than a one-on-one, interpersonal communication. It may also be used to update a team on activities for a given project, or to inform a specific group within a company of an event, action, or observance.

Memo purpose

A memo’s purpose is often to inform, but it occasionally includes an element of persuasion or a call to action. All organizations have informal and formal communication networks. The unofficial, informal communication network within an organization is often called the grapevine, and it is often characterized by rumor, gossip, and innuendo. On the grapevine, one person may hear that someone else is going to be laid off and start passing the news around. Rumors change and transform as they are passed from person to person, and before you know it, the word is that they are shutting down your entire department.

One effective way to address informal, unofficial speculation is to spell out clearly for all employees what is going on with a particular issue. If budget cuts are a concern, then it may be wise to send a memo explaining the changes that are imminent. If a company wants employees to take action, they may also issue a memorandum. For example, on February 13, 2009, upper management at the Panasonic Corporation issued a declaration that all employees should buy at least $1,600 worth of Panasonic products. The company president noted that if everyone supported the company with purchases, it would benefit all.[3]

While memos do not normally include a call to action that requires personal spending, they often represent the business or organization’s interests. They may also include statements that align business and employee interest, and underscore common ground and benefit.

Memo format

A memo has a header that clearly indicates who sent it and who the intended recipients are. Pay particular attention to the title of the individual(s) in this section. Date and subject lines are also present, followed by a message that contains a declaration, a discussion, and a summary.

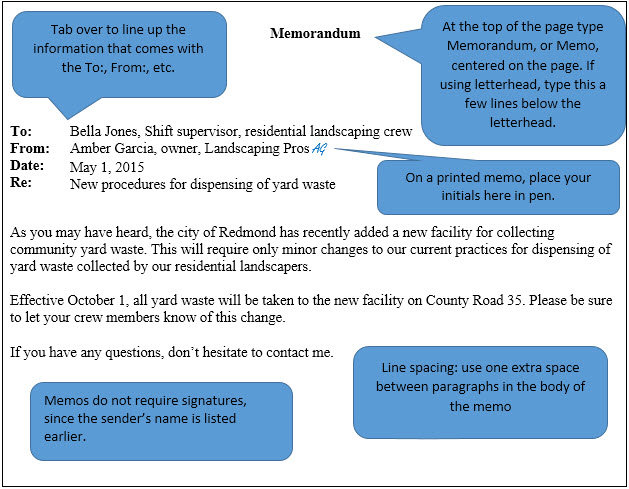

In a standard writing format, we might expect to see an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. All these are present in a memo, and each part has a clear purpose. The declaration in the opening uses a declarative sentence to announce the main topic. The discussion elaborates or lists major points associated with the topic, and the conclusion serves as a summary. Figure 2 provides a sample memo using the format explained above.

Figure 2. Sample memo (click image for an accessible PDF)

Five tips for effective business memos

Audience orientation

Always consider the audience and their needs when preparing a memo. An acronym or abbreviation that is known to management may not be known by all the employees of the organization, and if the memo is to be posted and distributed within the organization, the goal is clear and concise communication at all levels with no ambiguity.

Professional, formal tone

Memos are often announcements, and the person sending the memo speaks for a part or all of the organization. While it may contain a request for feedback, the announcement itself is linear, from the organization to the employees. The memo may have legal standing as it often reflects policies or procedures, and may reference an existing or new policy in the employee manual, for example.

Subject emphasis

The subject is normally declared in the subject line and should be clear and concise. If the memo is announcing the observance of a holiday, for example, the specific holiday should be named in the subject line—for example, use “Thanksgiving weekend schedule” rather than “holiday observance.”

Direct format

Some written business communication allows for a choice between direct and indirect formats, but memorandums are always direct. The purpose is clearly announced.

Objectivity

Memos are a place for just the facts, and should have an objective tone without personal bias, preference, or interest on display. Avoid subjectivity.

Letters

Letters are brief messages sent to recipients that are often outside the organization. They are often printed on letterhead paper, and represent the business or organization in one or two pages. Shorter messages may include e-mails or memos, either hard copy or electronic, while reports tend to be three or more pages in length. While e-mail and text messages may be used more frequently today, the effective business letter remains a common form of written communication. It can serve to introduce you to a potential employer, announce a product or service, or even serve to communicate feelings and emotions. We’ll examine the basic outline of a letter and then focus on specific products or writing assignments.

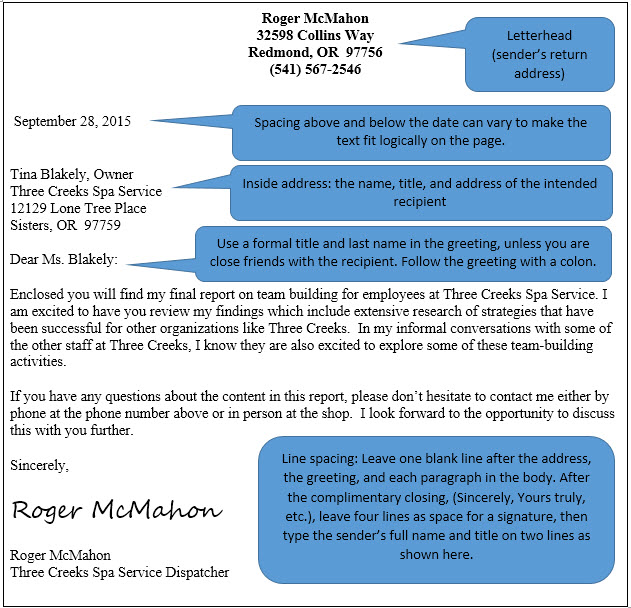

All writing assignments have expectations in terms of language and format. The audience or readers may have their own ideas of what constitutes a specific type of letter, and your organization may have its own format and requirements. This chapter outlines common elements across letters, and attention should be directed to the expectations associated with your particular writing assignment. There are many types of letters, and many adaptations in terms of form and content, but in this chapter, we discuss the fifteen elements of a traditional block-style letter. Letters may serve to introduce your skills and qualifications to prospective employers, deliver important or specific information, or serve as documentation of an event or decision. Figure 3 demonstrates a cover letter that might introduce a technical report to its recipient.

Figure 3. Sample cover letter (click image for an accessible PDF)

Strategies for effective letters

Remember that a letter has five main areas:

- The heading, which names the recipient, often including address and date

- The introduction, which establishes the purpose

- The body, which articulates the message

- The conclusion, which restates the main point and may include a call to action

- The signature line, which sometimes includes the contact information

Always remember that letters represent you and your company in your absence. In order to communicate effectively and project a positive image, remember that

- your language should be clear, concise, specific, and respectful;

- each word should contribute to your purpose;

- each paragraph should focus on one idea;

- the parts of the letter should form a complete message;

- the letter should be free of errors.

Letters with specific purposes

Cover letters. When you send a report or some other document to your supervisor, send it with a cover letter that briefly explains the purpose of the report and your major findings. Although your supervisor may have authorized the project and received periodic updates from you, s/he probably has many other employees and projects going and would benefit from a reminder about your work.

Letters of inquiry. You may want to request information about a company or organization such as whether they anticipate job openings in the near future or whether they fund grant proposals from non-profit groups. In this case, you would send a letter of inquiry, asking for additional information. As with most business letters, keep your request brief, introducing yourself in the opening paragraph and then clearly stating your purpose and/or request in the second paragraph. If you need very specific information, consider placing your requests in list form for clarity. Conclude in a friendly way that shows appreciation for the help you will receive.

Job application letters. Whether responding to job announcements online or on paper, you are likely to write a job application letter introducing yourself and your skills to a potential employer. This letter often sets a first impression of you, so demonstrate professionalism in your format, language use, and proofreading of your work. Depending on the type of job you are seeking, application letters will vary in length and content. In business, letters are typically no more than one page and simply highlight skills and qualifications that appear in an accompanying resume. In education, letters are typically more fully developed and contain a more detailed discussion of the applicant’s experience and how that experience can benefit the institution. These letters provide information that is not necessarily evident in an enclosed resume or curriculum vitae.

Follow-up letters. Any time you have made a request of someone, write a follow-up letter expressing your appreciation for the time your letter-recipient has taken to respond to your needs or consider your job application. If you have had a job interview, the follow-up letter thanking the interviewer for his/her time is especially important for demonstrating your professionalism and attention to detail.

Letters within the professional context may take on many other purposes, but these four types of letters are some of the most common that you will encounter. For additional examples of professional letters, take a look at the sample letters provided by David McMurrey in his online textbook on technical writing: https://www.prismnet.com/~hcexres/textbook/models.html

Chapter Attribution Information

This chapter was derived from the following sources.

- Online Technical Writing by David McMurrey – CC: BY 4.0

- Professional Writing by Saylor Academy – CC: BY 3.0

- Communicating Online: Netiquette by UBC Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology – CC: BY-SA 4.0

- Houston Chronicle. (2009, September 23). Deadly distraction: Texting while driving, twice as risky as drunk driving, should be banned. Houston Chronicle (3 STAR R.O. ed.), p. B8. Retrieved from http://www.chron.com/opinion/editorials/article/Deadly-distraction-Texting-while-driving-should-1592397.php↵

- Guffey, M. (2008). Essentials of business communication (7th ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson/Wadsworth. ↵

- Lewis, L. (2009, February 13). Panasonic orders staff to buy £1,000 in products. Retrieved from http://business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/markets/japan/article5723942.ece↵