PART III: Cognition and Coping

7

Cognition Behind Emotional Intelligence- A Learning Enhancement Program

Kira Dolan; Haley Mullen; and Mariana Paredes-Luna

Cognition Behind Emotional Intelligence: A Learning Enhancement Program

Emotional intelligence is explained as the capacity to be aware of, control, and express one’s emotions, and to handle interpersonal relationships judiciously and empathetically. It aids in our ability to recognize, label, and interpret one’s emotions, while simultaneously helps us to self-motivate and create positive social interactions. This plays a role in almost every situation we will encounter in our lives. With an absence or lack of emotional intelligence, we are likely to see a prevalence of mental illnesses such as major depressive disorder, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and substance abuse (Hertel, Schütz, & Lammers, 2009). In order to examine the development of emotional intelligence, one must analyze the cognition surrounding basic emotional development. Emotional regulation is vital in emotional intelligence as well as our ability to remain resilient, motivated, and committed to our goals. Through a learning enhancement wise intervention program, we hope to improve the part of the brain involved in emotional intelligence in hopes of creating stronger neural connections and an increase in overall emotional intelligence.

Currently, there are two scientific approaches to understanding emotional intelligence. The ability model views emotional intelligence as a standard intelligence and argues that the construct meets traditional criteria for a type of intelligence and should be measured as such (Brackett, 2011; Mayer & Salovey, 1997). This approach views emotional intelligence through an area of psychological research known as cognition and affect. This examines how cognitive and emotional processes interact to enhance thinking. The second evolution of thought involves the study of intelligence in relation to personality traits and competencies such as optimism, self-esteem, and emotional self-efficiency (Brackett, 2011), known as mixed models. While there is some debate about the ideal model to measure emotional intelligence, our learning program will focus on the cognitive processes in an effort to analyze and further develop emotional intelligence.

Cognition Defined

Cognition, as defined by Goldstein is the “mental processes, such as perception, attention, and memory, which is what the mind creates” (2019). In a sense, the mind is a system that creates representations of the world and enables us to act to achieve our goals. Other mental functions include memory, emotions, language, decision making, thinking, and reasoning. The term Cognitive Psychology was coined in 1967 by Psychologist Ulrich Neisser where he described it as the “study of mental processes, which include determining characteristics and properties of the mind and how it operates” (Goldstein, 2019).

On a scientific level, cognition starts within the structure of the brain. Spanish physiologist Ramon y Cajal studied Golgi stains and the brain tissue of young animals to discover that the nerve net was not continuous but instead made up of individual building blocks called neurons. This discovery created the foundation for the neuron doctrine, which can be summed up as “the idea that individual cells transmit signals in the nervous system, and that these cells are not continuous with other cells as proposed by nerve net theory” (Goldstein, 2019). The neuron is made up of the cell body which is the metabolic center of the cell. The cell body has dendrites that branch out and receive signals from the other neurons. On the other end of the cell body, there is an axon (nerve fiber) which is a long process that transmits signals to other neurons.

Cajal also discovered additional facts about neurons including that there is a small gap between the end of the axon and the dendrites of another neuron called a synapse. He also discovered that “neurons are not connected indiscriminately to other neurons but form connections only to specific neurons. This forms groups of interconnected neurons, which together form neural circuits (Goldstein, 2019). In addition to neurons in the brain, some neurons are specialized to pick up information from the environment, such as the neurons in the eye, ear, and skin called receptors. This radical idea that individual neurons communicate with other neurons in neural circuits was a monumental leap forward in understanding how the nervous system operates in the body.

The Process Behind Emotions

In reference to the neurological processes of emotional intelligence, emotions are processed in the amygdala, which is an almond-shaped, bilateral structure that connects to the medial temporal lobe of the brain. This key structure acts as a “smoke detector” that processes aversive information then sends signals to the hypothalamus which triggers “fight or flight” responses in the body. However, recent studies have found that the “amygdala is activated by emotionally arousing stimuli, regardless of whether they are pleasant or unpleasant” (Weymar & Schwabe, 2016). Further evidence has been found in studies using reward-learning, episodic memory encoding, pleasant scene or face perception, or mental imagery of pleasant experiences.

On a biological level, the bundles of the nuclei within the amygdala are activated when they receive input from various sources such as the cortex, thalamus, or hippocampus and in turn project to regions in the brain that mediates different forms of cognitive functions (e.g., vigilance, attention, and memory) to facilitate survival actions (Weymar & Schwabe, 2016). According to discrete emotion theory, primary emotions can be sorted by their specific psychophysiological pattern and defines emotions by two parameters: their valence (pleasant to unpleasant or positive to negative) and their intensity, also defined as arousal (calm to excited) (Bonnett et al., 2015). Overall, the amygdala plays an important role in the limbic system when detecting emotionally arousing stimuli in the environment.

The physical source of emotional intelligence originates in the communication between your “emotional and rational brains.” The pathway for emotional intelligence starts in the brain, at the spinal cord and must travel to the frontal cortex before you can think rationally about your experience (Bradberry, 2014). However, first, they travel through the limbic system, the place where emotions are generated. This helps to explain our emotional reactions to events before our “rational mind” can engage. Emotional intelligence requires effective communication between the logical and emotional centers of the brain. Experience-dependent plasticity is the term used to describe the brain’s ability to change depending on your experience (Goldstein, 2019). As your brain learns new skills, new neural connections are created and reinforced through consistent exposure. The change is gradual, as your brain cells develop new connections to speed the efficiency of new skills. Using strategies to increase your emotional intelligence allows these neurons between the rational and emotional centers of your brain to branch out and reach to other cells (Bradberry, 2014).

Perception

Perception plays a vital role in our everyday life. It is built on a foundation of information from the environment but also involves prior knowledge and expectations (Goldstein, 2019). It is not only about seeing what is around us but how our experiences and senses tie together to create cognition and bottom-up processing. In early psychology, Helmholtz brought up the theory that ambiguous neural signals are recognized via inferences. About 30 years later, the Gestalt School of Thought came up with the theory of perception being an organized inference and not a simple addition of senses that we encounter. This can occur in two different ways; top-down and bottom-up processes. Bottom-up occurs when the retina sends signals to the PVC in the occipital lobe, which activates the feature detectors and phase-sequencing occurs. Top-down is when phase-sequencing creates spreading activation and the recognition of the object is recalled. These also play a role in auditory perception and the way we break up sound or tell when one word in a conversation ends and the next one begins known as speech segmentation (Goldstein, 2019).

Perception is also pertinent to our emotional development. It is argued that infants form mental representations, or schemas, for the faces that they encounter in their everyday lives and are more likely to be afraid of people whose appearance is not easily assimilated into those existing schemas (Shaffer, 2008). Most infants are seen to react positively to strangers until they form their first emotional attachment, and then become apprehensive shortly thereafter. We typically see this peak at around 8-10 months of age. All of these emotional development milestones and theories are crucial when understanding emotional intelligence.

Attention

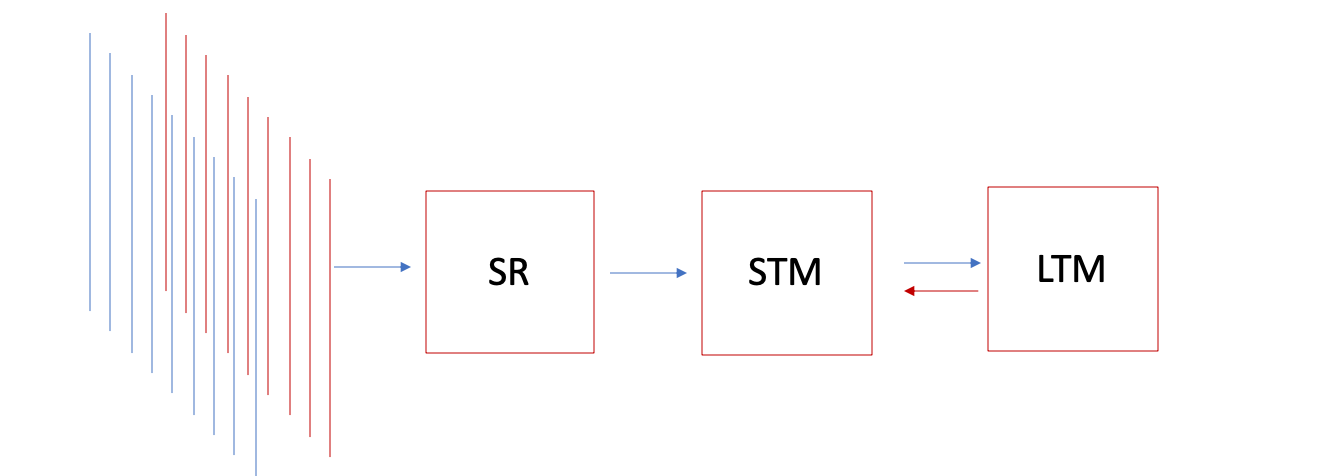

Attention is defined as the ability to focus on specific stimuli or locations and the mechanism that determines where we put our energy. It enables coordinated reactions to evoke stimuli in the environment; examples include threat detection and self-regulation. Today’s theory of attention includes the way in which sensory memory enters our brain and then travels to our short-term memory. If the information is important, it will travel to our long-term memory storage where it can be retrieved and moved back to our short-term memory when needed. Apart from environmental stimuli (stimulus salience), attention is also determined by higher level top-down processing such as scene schemas.

Attention can also be defined by neurology. Neuroimaging research has revealed that there are neural networks for attention associated with different functions (Goldstein, 2019). The ventral attention network controls attention based on salience and the dorsal attention network, which controls attention based on top-down processing. In relation to emotional intelligence, where one puts their attention can influence how one perceives the scene and the emotions that come with them. Top-down processing can be used as a tool for selective attention and to enhance emotional intelligence.

Types of Memory

Memory is the process involved in retaining, retrieving, and using information about stimuli, images, events, ideas, and skills after the original information is no longer present. Five different types of memory are sensory, short-term, episodic, semantic, and procedural. Sensory memory is the place where our brain receives all incoming bits of information for only seconds at a time. Meanwhile, short-term memory (STM) is the brain space where our control processes are operated on a selection of information that is taken from our sensory memory. Unlike sensory memory, these several pieces of information can be held for 15-20 seconds before disappearing from the mind or making its way to long-term memory; mentioned later in this paper. For example, if you remember what you have just read, that last sentence is now in your short-term memory. Even though information is lost relatively fast in the STM there is a limit to how many items of information can be held at once. Estimates of how many items can be held in STM range from four to nine (Goldstein, 2019).

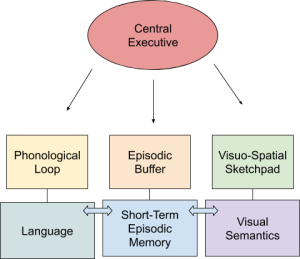

Along with STM there comes another type of memory known as working memory. Working memory is a storage system in the brain for temporary information and where manipulation of information occurs. We manipulate information that is more complex such as comprehension, learning, and reasoning (Goldstein, 2019). These three sections of information are what make working memory and short-term memory different from the other. However, both play a part in memory and remembering short-term and temporary items given to us such as numbers and words as researcher Baddeley would soon bring to light in an experiment. During his studies he found that his participants were able to remember a series of numbers while also reading. Baddeley took this into the conclusion that we are able to do two things at once in the working memory, which meant that we had a number of components that function separately; the phonological loop, visuospatial sketchpad and central executive.

The phonological loop is where language is held and is brought into perspective in three different phenomena such as the similarity effect. This is where the confusion of letters or words that sound similar are found (Goldstein, 2019). This was found by R. Conrad (1964) by flashing a series of letters onto a screen and having participants describe the letters they saw. He found that the participants misidentified the “target letter” with other letters that had a similar sound such as Z, S, and X. The second phenomena is the word length effect that occurs when given a list of words that are better remembered when short rather than long. Researchers concluded this was because longer words take longer to pronounce and rehearse during a recall. The last phenomena is called articulatory suppression that is described as the repetition of a word or sound. This action has been found to reduce memory as speaking interferes with the rehearsal of the word or sounds. The visuospatial sketch pad is the part that handles visual and spatial information brought in, Therefore, this section is part of the visual imagery that is the creation of visual images in the mind and gives a visual stimulus to help the long-term memory retrieve memory.

Another section of the short-term memory is the central executive that makes the working memory “work” or referred to as the attention controller (Baddeley, 1996). The mission of the central executive is to help store the information given and coordinate how and where it is used in the other loops; phonological and visuospatial. This part of the memory is the place in which we tie together the phonological and visuospatial parts of memory in order to coordinate essential functions in specific tasks. This determines how your attention is split in between two tasks and how it is switched between the two.

In contrast to short-term or working memory, which only lasts for about 15-20 seconds, Long-term memory (LTM) is the stage of the memory model where informative knowledge is held indefinitely. Long-term memory consists of two processes: encoding (the process of acquiring information and transferring it to LTM) and retrieval (bringing information into consciousness by transferring it from LTM to working memory) (Goldstein, 2019). There are several mechanisms of encoding that assist in transferring information into LTM, which include maintenance rehearsal and elaborative rehearsal. Maintenance rehearsal is when you hold a piece of information in your mind and repeat it over and over. This type of rehearsal results in little or no encoding which is why the information is not remembered later and thus it is not an effective way of transferring information into LTM. On the other hand, elaborative rehearsal is when you take the same information but apply meaning to it or make a connection to another subject in order to remember it more effectively. Overall, this method is a better way to establish long-term memories.

Information Processing

According to the levels of processing theory, memory depends on how information is encoded or programmed into the mind. In fact, this theory elaborates that “shallow processing is not as effective as deep elaborative processing” based on an experiment by Craik and Tulving in 1972 (Goldstein, 2019). This concept relates to the types of rehearsal above where shallow processing involves little attention to meaning and deep processing involves close attention and elaborative rehearsal that focuses on the meaning of an item and its relationship to the world around it. Several studies have shown that encoding influences retrieval based on research that examines the effect of “(1) forming visual images, (2) linking words to yourself, (3) generating information (the generation effect), (4) organizing information, (5) relating words to survival value, and (6) practicing retrieval (the retrieval practice effect or the testing effect)” (Goldstein, 2019). Overall, these tactics have been proven to increase retrieval from long-term memory.

In addition to those tactics, there are five specific memory principles that can be applied to studying to aid the encoding of information. These are (1) elaborate, (2) generate and test, (3) organize, (4) take breaks, and (5) avoid “illusions of learning.” Elaboration is a process that helps to transfer the material being read into LTM by thinking about the content and giving it meaning by relating it to previous knowledge. Generate and test and organize are exactly what they sound like, coming up with information, sorting it in your mind, and testing yourself over and over. In addition, taking breaks also helps to improve memory, known as the spacing effect. Also, it has been proven that sleeping soon after studying can improve a process called consolidation (Goldstein, 2019). Lastly, it is important to avoid misconceptions about specific study techniques which may appear to be more effective than they actually are.

Consolidation

Going further into consolidation as mentioned above, consolidation can be defined as the “process that transforms new memories from a fragile state, in which they can be disrupted, to a more permanent state, in which they are resistant to disruption” (Goldstein, 2019). Of the two types of consolidation, synaptic and systems, incorporating systems consolidation is a better fit for our learning program. Systems consolidation is the wiring of networks in the cortex that requires the looping in of the MTL (Medial Temporal Lobe), which involves the reorganization of neural connections and it takes place over a longer time span than synaptic consolidation. This process is enabled by long term potentiation, a persistent strengthening of synapses that produce a long-lasting increase in signal transmission between two neurons, which takes place in the hippocampus.

Visual Imagery

Earlier you read about the working memory model and how it shows us that a large part of our cognitive resources are put towards visual-spatial processing. With this in mind, then, it is not surprising that visualization can have a strong impact on our ability to recall information from our long-term memory with the use of pictures. In this section we present a couple of methods that use visual techniques that will help items of information store into the long-term memory by visual-spatial processing. The first is called the method of loci which is defined as a method in which things to be remembered are placed at different locations in a mental image of a spatial layout (Goldstein, 2019). By placing things in locations you have a greater chance of retrieving memories. So, how do we use this? In terms of memory and our emotional intelligence program, we can use images to help the participants keep a stronger image of a proper emotional response along with a stronger recall. By seeing the images repeatedly this would help the emotions and situations get to the long-term memory and will hopefully allow for a shorter recall time. By teaching to visualize these emotions in another physical space they will have a greater recall and perform the corrected response.

Another method that was mentioned is called the pegword technique. This is similar to the method of loci, except instead of visualizing items in different locations, they will associate those items with words. In the case of our program it would be associating words with specific emotional responses. This could be the greater option in our program as far as visualization as having a trigger word or “calming” word is easier to implement than having them recall different locations for an attachment with emotions. This can be done by rhyming the words with the desired cue as well as pairing the word with things to be remembered around it such as your own image/representation of the word. Both of these methods could be used for the younger participants to give them a more fun sense of learning and remembering the methods behind our program.

Emotional Intelligence and Achievement

While the cognitive basics of emotional intelligence give us a better grasp of its functioning, the significance of emotional intelligence can be seen through past and recent research. A number of studies have examined the impact of emotional intelligence on academic performance. Its impact can be seen with grade school children all the way through college. A developmental study conducted by Izard et al. (2001) found that five-year- old preschoolers’ emotional knowledge predicted third-grade teachers’ ratings of academic competencies (e.g., arithmetic skills, reading skills, the motivation to succeed). Halberstadt & Hall (1980) reviewed 22 studies (5 of which included adult populations) of nonverbal sensitivity (including emotional perception) and found a small but significant positive relationship between the ability to identify nonverbal expressions and cognitive ability assessed by standard tests and school performance. Emotional intelligence has also been negatively associated with maladaptive lifestyle choices. Lower Mayer–Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) scores measuring emotional intelligence among male college students were related to higher levels of drug and alcohol use as well as stealing and fighting (Brackett et al., 2004; Mayer et al., 2004). The purpose of our learning program is to increase emotional intelligence to enhance understanding, labeling, expressing and regulating emotions. In turn, we expect this to improve one’s social relationships, aid in decision making, and overall improve one’s way of life.

Wise Intervention

According to Gregory M. Walton at Stanford University, a wise intervention is a method of removing the obstacles that prevent people from flourishing, which depends on a precise understanding of an underlying psychological process and the individual’s psychological reality (2014). The aim of a wise intervention is to “simply alter a specific way in which people think or feel in the normal course of their lives to help them flourish” (Walton, 2014). When creating a wise intervention, researchers need to identify an aspect of people’s psychology that harms their life outcomes and work to alter this negative process. Thus, wise interventions must be psychologically precise and focus on a specific, well-founded psychological theory. This precision allows researchers to create a tool that can bring real change to a specific psychological process in a real-world setting. Once the psychological theory is established, the next step is to create a brief intervention that will alter self-reinforcing processes and thus improve people’s circumstances.

More specific examples that relate to our program are under the wise interventions that capitalize on the need to understand as they focused mainly on the self, other and personal and social interactions. One of the example studies mentioned talks about how people instigate negative feelings or states to worry. In this study, they examined that by teaching college students that the physiological arousal that occurs while taking a test is the body being ready to accomplish something important and not a failure, it can raise GRE performance for up to 3 months after. By teaching the individual a new way to change their beliefs about their own emotions then helps them to perceive situations in a different way that can be a more beneficial outcome.

A second study that was helpful focused on the self, oneself and selves in general. This study is similar to our study in terms of focusing on the individual involved and their actions rather than others around them. It is emphasized that changing how people make sense of their self-identity can lead people to behave accordingly, which is achieved by a technique known as direct labeling. The children in this study that were told by a teacher and principal that they were “litter conscious” were less likely to litter than the other children who were not told. This meant that those who had earned a title had internalized it. This is similar to our program by changing the view of self and giving them more of a motivation to reach desired goals and change their views on their own behaviors.

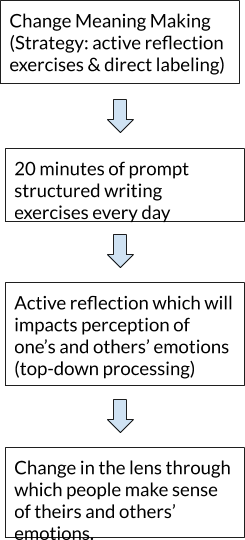

Active reflection exercises have been shown to help people reframe their experiences, often through writing. Through these exercises, participants are asked to write in open-ended ways in response to structured prompts that help to reinterpret events and situations on their own. A study conducted by J.W. Pennebaker (1997) (Mayers, Roberts, & Barasade, 2008) focused on asking people to write about negative experiences. This allows people to think more clearly and find resolutions or positive meanings in them to improve functioning. However, this is just one type of reflection exercise. Other studies have focused on value-affirmation exercises that aim to mitigate the psychological threat by reconnecting people with core personal values (Mayers et al., 2008). We hope to create a meaningful difference in the person’s attention and attention processing. Through active reflection exercises, participants will be prompted to think deeply about daily experiences in hopes of changing their perception of daily occurrences.

While these studies are helpful when examining emotional intelligence, a more holistic wise intervention would include a mixture of active reflection exercises and direct labeling. Through this specific intervention, participants would be able to organize daily events in hopes of encouraging reflection on emotional-related occurrences. Through the process of direct labeling, we will be using prompting with leading questions. Leading questions assume an idea and encourage people to elaborate on its significance. This allows the participant to interpret events on their own, however, it continues to keep a goal in mind. As a result, we expect to see an increase in understanding of both theirs and others’ emotions. The logic model below helps to better understand this process.

Training Program

The aim of any wise intervention or learning enhancement program is to improve daily living. As we have noted, emotional intelligence is a crucial part of everyday life and through past and present research, we know that emotional intelligence can be learned and developed. It is reasonable to conclude that the most effective way to enhance emotional intelligence is through daily reflective exercises. For someone seeking to improve their emotional intelligence, we suggest daily reflective writing exercises that focus on their daily in-person interactions. This should include observations of others’ reactions and emotions, one’s reactions to others, and an examination of how one’s actions will affect others. These exercises could include leading questions such as, “Put yourself in their place, how would you feel in their shoes?,” “How could a specific interaction be handled differently in order to avoid hurting your friend/coworker/family member’s feelings?” This allows for further understanding of person-to-person interactions. From here, direct labeling can be beneficial in specifically labeling what emotions arise in specific situations, how others react, as well as labeling how your actions impact others. Through consistent reflective writing exercises, we hope to improve emotional intelligence and in turn, one’s daily life.

On a cognitive level, we must implement visual and semantic details to start the bottom-up process and begin the sequencing processing of the stimuli that are used. Semantic regularities are important to use in this training as we are trying to increase cognition that is relative to understanding and expressing emotions. The use of semantic regularities are important in this program as they are characteristics associated with the functions carried out in different types of scenes (Goldstein, 2019). This is a beneficial tool to use, as giving more inputs or stimuli that relate to the same object can be advantageous because there are now more than one stimuli that will start the top-down processing once those neurons have fired together numerous times. This relates to our program as we are trying to enhance the expression of emotions and reactions for those with a lack of emotional development. In order to use visual and semantic regularities effectively for enhancing emotional intelligence, one can show scenes or examples of proper expressions of emotion and reactions in certain situations that may happen frequently. This will allow for the person to use visual cues to label specific emotions and through consistent reflective writing exercises, they will be able to recall how to properly react.

With studies that support the theory behind visual or sketchnoting techniques, the implications of visual details would be ideal for this program. In one study presented, Kleinknect presents us with data that shows the average correct answers from students who used visualization, sketchnoting, and listening to recall a set of words. The visualization recall data showed the average correct answers as 11.58, sketchnoting was 11.62 and listening was 9.77 of 15 total questions. This data supports Sunni Brown’s claims that “doodling” or visualization and sketchnoting help to affect memory by increasing retention, creative problem solving and deep information processing (Brown, 2011). With this in mind, using visual details in our learning program is important to help participants better retain the information they are being presented within the program. This is another input, or “route in,” we can implement for clients to encode learning information. This can be used as a way of giving examples of the desired emotional reaction in situations that relate to the participant or their family.

Our program focuses on enhancing the understanding, labeling, expressing and regulating emotions. The person-centric example, in particular, is about helping individuals with initial poor qualities such as a lack of skills or poor character and training the way they focus on their own behaviors and others’ personal interactions as well. Therefore, this ties closely with our program in terms of the desired outcomes. Wise interventions have been shown to increase minority students’ success, decrease the rate of child abuse with at-risk mothers, increased voter turnout, along with many other significant impacts. With our learning enhancement program, we aim to broaden its impact and improve emotional recognition and the ability to use this information to guide thinking and behavior and improve overall emotional intelligence. This social-cognition approach can be a simple, yet powerful tool to improve the lives of many.

Along with the help of this wise intervention program we will be able to help readers get a better understanding of not only what cognition is and how it works, along with the concepts that go along with it. This includes focusing on attention, perception, the process behind emotions, information processing and different types of memory. By giving background information and examples on specific topics such as emotions and information processing we help to lead into different areas of cognition that helps readers understand why this program is efficient and holds potential to increase knowledge of emotional intelligence. Overall, this guide can be helpful in many ways with emotional intelligence being just one of the benefits to this program.

References

Bonnet, L., Comte, A., Tatu, L., Millot, J.-L., Moulin, T., & Bustos, E. M. D. (2015). The role of the amygdala in the perception of positive emotions: an “intensity detector.” Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 9. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00178

Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., & Salovey, P. (2011). Emotional intelligence: Implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 88-103.

Bradberry, T. (2014, October 8). Emotional Intelligence – EQ. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/travisbradberry/2014/01/09/emotionalintelligence/#6019daf11ac0

Ciarrochi, J., Deane, F. P., & Anderson, S. (2002). Emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between stress and mental health. Personality and individual differences, 32(2), 197-209.

Goldstein, E. B. (2019). Cognitive Psychology: Connecting Mind, Research and Everyday Experience, 5th edition. Boston, MA. Cengage

Hertel, J., Schütz, A., & Lammers, C.-H. (2009). Emotional intelligence and mental disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(9), pp. 942-954.

Mayer, J. D., Perkins, D. M., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (2001). Emotional intelligence and giftedness. Roeper review, 23(3), 131-137.

Mayer, J. D., Roberts, R. D., & Barsade, S. G. (2008). Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 59, 507-536.

Salovey, P., & Grewal, D. (2005). The science of emotional intelligence. Current directions in psychological science, 14(6), 281-285.

Shaffer, D. R. (2008). Social and personality development. Vancouver: Crane Library at the University of British Columbia.

Weymar, M., & Schwabe, L. (2016). Amygdala and emotion: The bright side of it. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 10. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00224