PART I: Cognition and Learning

2

A New Look at Learning Styles: How to Wisely Apply Encoding Variability to Education

Bradley Altomare; Christopher Chuckas; and Robert Gordon

As a student, there are always moments in learning that stand out more than others. Whether it be a certain activity, a certain teaching style, or a certain fact from a random class in high school, certain aspects stick better, and majority of the time, the reasoning behind that is unknown to the individual. For most people, it is rather simple to memorize lyrics of a song, memorize a playbook for a game that week or the route from home to work. Whatever it may be, these aspects of life seem to be easier to remember than a subject for an exam. Why is this? It is not because the material is more difficult or less intriguing to most, it comes down to the fact that the standard form of teaching (that revolves around unoriginal and basic learning styles) doesn’t create the most optimal success when students are involved in encoding information. Encoding is the process of acquiring information and transferring it into memory. This psychological concept is not only one of the main principles in a student’s everyday life, but it is also one of the most difficult concepts to grasp, and the correlation between successful encoding variability and teaching methods has become a new foundation in teaching.

Cognitive learning styles come down to an individual’s information processing habits, each style offers its specific pathways for remembering and retaining an experience. Ultimately, cognition describes a person’s routine mode for perceiving, thinking, remembering, or even problem-solving. There is a popular notion of learning styles that the best way to learn is different from person to person based on the three basic learning styles which are categorized as visual, auditory, and kinesthetic. Learners who prefer to engage their visual systems best absorb information when they can see the material being presented. They often associate certain subjects, ideas, and tasks with images, videos, or any other visual stimulus. Learners who prefer to engage their auditory systems retain information through listening and speaking. To fully comprehend certain stimuli, these learners prefer to hear information, verbally repeat them, or think in terms of acronyms using a language shortcut to remember certain details. Learners prefering to engage their kinesthetic system requires that they manipulate or touch material to learn. They often find success in making models or interacting with the environment to naturally discover information that can be stored as an experience related to the stimulus. Following the pop-culture ideas of “learning styles”, teachers are often encouraged to find ways to get their students more engaged in learning, thus producing better results.

Does this sound familiar to you? Well, as the cognitive science perspective would have it, that is an incorrect notion. Cognitively, the standardized VAK-learning styles have backed students into a corner of unproductive motor learning systems. With Visual, Auditory and Kinesthetic learning being the main three elements of identifiable learning, teachers (and others who are in charge of influencing learning) have unintentionally grouped individuals into one sensory motor learning style, which according to modern Cognitive Science, eliminates the motivation and confidence to learn in a multitude of ways thus hindering the learner rather than benefiting them.

With the different learning styles come different ways one can apply and use them. A student who prefers visual learning over auditory is going to have different techniques and things to help them learn. One of these techniques we’ve learned about that engages different parts of your brain and helps learners who prefer to engage their visual systems is sketchnoting. Sketchnoting is an alternative way of taking notes that engages the occipital lobe of your brain. This is a really helpful strategy for learners who want to incorporate visual details into their studying routine because they can associate icons and images to the material rather than just words. This allows you to utilize your Psy-i-con alongside your Lexicon when learning. Psy-i-con is your mental dictionary of images and Lexicon is the mental dictionary of words and the meaning behind them. Sketchnoting takes advantage of both of them and utilizes the whole brain, which makes it that much more ideal.

With that being said visualization is very important with learning and memorizing. We need to take advantage and use images to help our memory. Creating and using images can help comprehension and enhance encoding retrieval. When words are consciously used to create mental images, understanding is facilitated. Consequently, people who utilize visualization have an advanced ability to understand, learn, and remember. Processing information using your visuospatial sketchpad and visual semantics can help store information in your long term memory. This can all be utilized in learning.

Then with the other two modes, auditory and kinesthetic, there are many ways to apply them to your learning. Somebody who associates more with auditory learning will prefer to have someone go over it with them and they’ll usually like to read things out loud. Then with learners who prefer to engage their kinesthetic system, you’ll find them going through the whole physical process of things. How learners who prefer their visual systems may resort to sketching, learners who prefer to engage their kinesthetic system will look for things in the real world they can use as tools to apply their learning, and with preference of auditory engagement, they may prefer recordings, collaborative dialogue, or even online lectures.

There are plenty of ways to incorporate the other modalities into a singular lesson plan. For the purpose of keeping the classroom engaged and ready to learn, utilizing all modalities gives you an opportunity to “keep the class on their toes”. A simple way to include each modality could be through organizing your lessons strategically, such as showing a historic film then asking the class to reenact the film, using auditory skills to interpret and vocalize the information, while using visual and kinesthetic measures to recreate and organize the film cognitively. A lot of incorporations can be seen as “real-life applications”, like teaching kids how to measure, which can be done in a variety of scenarios like cooking, building, and arts, implying that all of these measures can be taught using the physical act (kinesthetic), making it a group project where communication is prevalent to include auditory, while also using visual representations such as a cook book, pictures, etc., in order to facilitate the lesson’s attractiveness and memorization. The fact of the matter is we all learn in similar ways no matter the preference, and the best way to maximize how and what we learn is to have our study practices be congruent with our testing practices. This is a key principle of encoding variability and encoding specificity. On top of that, it is important that students dictate that when encoding not only do they want to match study to test, but when studying you want to blend sensory modalities as well.

Cognition is our ability to process information through perception, it is our active thoughts and sensations about the stimulus that form and take up storage ready for retrieval. Information processing is an approach to the mind that psychologists have created which traces the sequences of mental operations involved in the mind. This approach allowed scientists to ask questions and frame their answers in different ways, transitioning researchers to wanting to understand how well the mind can deal with incoming information (Goldstein p. 15, 2013).

When psychology was shifting to behaviorism there was a view from which psychology should be considered an objective science since we can study behavior without reference to mental processes because we can interpret or document actions in regards to retention and active cognition. This led to many examinations of cognitions throughout the field bringing upon concepts such as classical and operant conditioning which examined how people create links to multiple stimuli and associate two unrelated stimuli with each other.

In the 1950s however, scientists gravitated towards the idea that cognition wasn’t exactly based on behavior, but that humans can only interact with the real world through interconnecting, complex systems that process stimulation like sensory input. The modern study of cognition is of these systems and the ways they process information from the inputs of a stimulus. The processing of the mind includes not only the initial structuring and perception of the input but also the storage for later retrieval. The main paradigm for cognitive psychology has been the information processing approach, observing and analyzing the mental processes involved in perceiving and handling information using mental processes such as encoding, storage, retrieval.

We know our brain does this through the use of technology in a process called brain imaging. There are a few ways we can visually determine that the brain functions in such a manner. We can use fMRI’s (Functional magnetic resonance imaging) to measure brain activity by detecting changes associated with blood flow to see the different functions and firing of the brain’s cortices. We can also use a PET scan (positron emission tomography) which reveals how tissues and organs are functioning through a radioactive drug tracer to show this activity in real-time. One of the ways cognition is examined scientifically is deriving the question of, “How can nerve impulses stand for different qualities?” (Neurons create and transmit information about what we experience and know, which is done through nerve impulses in the brain in reaction to stimulus). There are many situations in our everyday life that allow our neural networks to work and fire together.

When learning how to drive at a young age, the streetlight is one of the first cognitive stimuli we can understand and react to. This is due to the use of feature detectors allowing our neurons to specifically code each color to the action of driving (E.G., Green = GO, Yellow = Yield, Red = Stop). So how does our brain establish the memory of such a task? Memory is one of the most difficult concepts to fathom in terms of cognitive neuroscience, but it is also one of the staples in understanding learning styles. Memory in basic terms of neuroscience is the re-creation or reconstruction of past experiences by the firing of neurons. Memory encoding is the acquisition and storage of stimulus or experiences. Memory goes hand in hand with how we learn and allows us to appreciate how our senses, perceptions and actions can become memories. The brain comes with what is understood as a neurological starter set, that we are wired to remember so our experiences can be coded into our brain based on our experiences. This is just like processing information when it comes to learning.

Experience dependency is the actual connections that occur as we experience specific environmental energy, while sensory codes refer to how neurons represent various characteristics of the environment. Each section of the brain has specific functions (i.e the Fusiform face area, Extrastriate body area, Parahippocampal place area or cortices such as the occipital lobe controls vision), yet every individual’s brain is wired slightly different based on the plasticity of their brain, which is when the structure of our brain changes with experience (Goldstein 2015, p.34, 42). Every person has a similar occipital lobe, which houses the the ventral stream (visual-perception pathway) which is mainly responsible for recognition and discrimination of visual shapes and objects.

Each person has a similar temporal lobe, which contains the dorsal stream ( visual-action pathway) which has been primarily associated with visually guided reaching and grasping based on a moment-to-moment analysis. However, with experience-dependent plasticity, every person’s brain is structured a little differently based on their personal experience. Memory is an interconnected, complex, and extensive storage space that works together like a web. Neural networking refers to the idea that we have this “web” of neural changes in the brain that underlie cognition and perception in which a large number of simple hypothetical neural units are connected to one another, meaning that information is entirely interconnected, but has individual pathways for access. It comes down to the neurological underpinnings of spreading activation and encoding variability. This is why with our specific topic of learning styles you can really see how a learning situation can be enhanced when multiple sensory systems are stimulated, because they engage the learner in many different ways, as well as creating the maximum amount of representation in the brain, leading to more effective learning.

On the surface, it may be hard to find the connection between perception and the different modes of learning, but that’s because we use perception without even knowing. Our brain is hardwired to just naturally do it, then experience is what adjusts it to each individual. With that being said, we first have to establish everybody perceives things differently and this will affect everybody’s learning differently. For example, people may see or notice different things when a teacher is going over the lesson. A learner who prefers to engage their auditory system isn’t going to pay as much attention to imagery or diagrams as much as a learner who prefers to engage their visual system would. This due to a habit that students develop when being categorized as a specific learner. Someone who prefers to listening, will display less attention to visual details. Although, this doesn’t provide disadvantages with different learners because of the way each of our brains is wired. We all have the base starter kit to be able to do anything we need, just some have more experience and comfortability than others in certain regions, and a large reason is that the categories young learners are assigned to.

The connection between the visual aspect of learning and perception is crucial. From being able to tell things apart, label what’s more prevalent, or just identifying what’s what we use perception in every aspect of life and learning. This then ties in with the other modes. Kinesthetic is very hands-on so maneuvering objects has a lot to do with perception. The textbook labels it as the interaction of perception and action. They provide an example of a cup on a table with “obstacles” around it. You use perception to reach around the obstacles and only grab the cup without knocking anything else over. Anything we do with our hands and feet involves perceiving what to do. In the brain, this takes place in the dorsal and ventral pathway, which is also known as the “What”(Ventral) and “Where” pathways (Dorsal). The what pathway is the one that controls the perception and the where pathway controls the action of one doing it. In everything we do we’re constantly learning new things no matter what mode of learning it is, they all use perception in different, crucial ways. On top of the pathways in our brain that tell us where and what things are and how to navigate with them, our brain contains mirror neurons which allow us to associate things even if we ourselves are not doing the action. For example, mirror neurons would respond to both seeing someone else grab a pencil and write as well as when that person physically picks up the pencil and writes themselves. These mirror neurons were one of the largest discoveries in cognitive psychology that also opened up a world of understaining in our brains “code”.

“Multiple Codes” are a base for our brain and cognition, it’s taking everything we learn and blending it all to make sure we aren’t missing any aspects. In learning, it’s inevitable to use auditory, visual, and kinesthetic learning all at once. For example, if you went on YouTube and watched a “How To” video, you will be engaging in all three modes throughout the video, you’d be visually learning by watching them act, you’d hear their instructions as they go on activating your auditory mode, and lastly if your following along with the action and doing the actual process you’re learning through the kinesthetic mode. This is all due to the multiple codes we have that we can take in more than one thing at a time. Without this, we wouldn’t be able to function properly as humans and the learning process would be up to three times the time it takes to learn with them. In the context of learning, it is important to stimulate multiple routes in the brain because the more routes that are utilized the richer the experience in understanding the knowledge.

In terms of the three optimal learning styles, having a vast level of analysis is extremely important for students. Levels of analysis can refer to the idea that a topic can be studied in several different ways with each approach contributing its dimension to the understanding (Goldstein 2015, p.26). An example of this in terms of the classroom can be found in most science courses today. Having auditory and visual learning in the classroom, While having hands-on kinesthetic learning in a lab on the same subject creates vast utilization of multiple pathways.

In terms of Cognitive Psychology, attention is defined as the ability to focus on specific stimuli or locations (Goldstein 2015, p.95), from an evolutionary angle, attention is an adaptation that enhances reproductive fitness because it allows an increase in reproductive fitness because of the gain in survival. Attention makes perception possible which guides action which enables coordinated reactions to evocative stimuli in the environment. The theory around why attention is such a big part of the evolution of psychology is that attention is the mechanism that determines where we put our energy.

Another important aspect of information retention is working memory, which is defined in the world of Cognitive Psychology as a “limited-capacity system for temporary storage and manipulation of information for complex tasks such as comprehension, learning, and reasoning (Goldstein 2015, p.143). On the other side of the memory spectrum, long term memory is a memory mechanism that can hold a large amount of information for a long period of time, long term memory is also one of the stages in the model of memory (Goldstein 2015, p.162).

These processes go hand in hand with individuals and their learning styles. Attention is so important when it comes to learning. With that being said, if you can match the styles to the individual one’s chances of paying more attention and storing information increases. If the student is more engaged they will pay more attention and be less susceptible to mind wandering. Since, attention is where we put our energy, we want it to be used in the most efficient way possible when it comes to learning.

With working memory, we are constantly manipulating information and learning new things. The way we manipulate this information and temporarily store it can be a factor in how successful we may learn. Information we don’t prioritize and pay much attention to is not going to last long in our memory, thus proving why taking advantage of multiple styles of learning at once and encoding variability are important for maximizing our learning. Then what information we take in successfully we can store it in our long term memory. All of these processes can be put to use whether it’s in the classroom, sports, or anywhere else one may be learning.

One aspect of the human brain that is incredibly convenient is our ability of neuroplasticity. We know that with the right stimulation, your brain can form new neural pathways, alter existing connections, and adapt and react to new and unexpected stimuli in a variety of ways. Aspects of cognition such as attention, long term memory, and working memory can all be improved. An area such as attention can see growth with a few changes such as meditating (focus on stimulus), and avoiding multitasking (e.g., homework and twitter), which will help clear up valuable working space necessary to comprehend and remember the material you’re working on. Another idea for improving attention could be to challenge the brain by working through harder topics and provoking an explanation that establishes a new, or remodels an old pathway.

The Wise intervention is an approach to certain problems that involve basic theory and research. Though the Wise Intervention idea originated in a social psychology context, the main principle of it applies just as much in all the subfields of psychology. This approach takes working hypotheses people draw about themselves, other people, and social situations and then finds how different meanings social and cultural contexts can have. These interventions also see how changing meanings of these views and situations can affect people. This also measures how change can affect and alter people’s lives. There’s so many other benefits to a Wise intervention that include social reform, meaning-making, and objective changes in situations or individuals. The overall purpose of having this intervention is to provide a comprehensive review and organization of a psychologically informed approach to understand and change human behavior.

The definition of “Wise interventions” are interventions that focus on the meanings and inferences people draw about themselves, other people, or a situation they are in and use precise, theory and research based techniques to alter these meanings (p. 618). These interventions are considered “psychologically wise”. The term “wise” in this sense means something different than it typically does. By “wise” they do not mean “good” or “superior” or that other approaches are “bad” or “unwise”, just that you take these lessons away from the studies.

With this comes five principles that characterize these interventions and change meanings. The first principle is that wise interventions alter specific ways people make sense of themselves or social situations. They are not general sayings like, “Be nice to them!” or “Just be positive!” They address specific psychological questions people have. Such questions often arise from sociocultural contexts. The reading gives an example of in school, students who face negative stereotypes and underrepresentation can wonder whether “people like me” can belong (p. 619). The second is that subjective meanings do not work in a “vacuum”, but within complex systems. They will improve outcomes only when other aspects of the system necessary for improvement are in place. Thus, removing a psychological obstacle to learning in a setting that does not offer opportunities to learn will not help (p. 619). The third principle is changing meanings to become more self sustaining.

When meanings are detrimental, such as critical feedback of the self or of social relationships, people can think and act in ways that become self-fulfilling (p. 620). Fourth, as with any attempt to change behavior in applied settings, wise interventions should be tested rigorously, with randomized field experiments. Development typically starts small, often in laboratory research, with the goal to clarify key meanings, their nature, consequences, and to further one’s psychological wisdom (p. 622). The fifth and last principle is to test interventions at each step. For not only ethical reasons, but scientific it is vital to follow these measures (p. 622).

Then three basic motives that guide meaning making and have been central to psychologically wise interventions are the need to understand, the need for self integrity, and the need to belong. Specifically, we need techniques that capitalize on these motivations that will end up changing meanings. After these motives are established, you can then organize them into different families based on what their motives are. A distinct difference you’ll find in these wise interventions, is comparing them with their approach and goal of social reform. Whether it’s looking to change the qualities of situations or people you can put them into the different “families”. Psychologically wise interventions do not address the objective qualities of either people or situations. Instead, they assume that subjective meaning making. It looks at how people make sense of themselves and social situations. Then how it can prevent people from taking advantage of opportunities for improvement already available to them. When it comes to the context of learning, pop-culture is providing learners with a sense of belonging due to suggesting that we each have a central learning style which dictates our possibilities for success. This framework created by pop culture sets people up to think about learning in only one way. Unfortunately, cognitive science does not support the idea that individuals differ in such a way.

In recent years, there has been an emergence of these new interventions. These interventions are everyday experiences. They aim to alter a way someone thinks or feels about these experiences to improve their life. For example, holding your temper in an argument or just something simple like encouraging your children. All of these different situations can be looked at and improved. One of the main things to do prior to performing these, is to make sure to ask yourself, “What is the psychological process at hand?”

Along with wise interventions, there come “Do’s” and “Don’ts” that you want to make sure you build your intervention around. In order for it to be considered a wise intervention, the situation or self reform must be wise to the population and context in at least three ways. First, a wise intervention will only be effective if the process it targets matters in the setting at hand. For example, if people with high self esteem are always accepting compliments, interventions that address self-esteem will not improve their relationships (p. 79). Second, wise interventions will be effective only if they change the targeted psychological process. To be maximally effective in different contexts, interventions may need to be adapted and changed. A way to view it is illustrating the message in a local setting, along with using exercises that drive home key ideas. The third stipulation you need to make sure of is that wise intervention will affect long-term outcomes only if they alter the critical recursive processes. For example, brief value-affirmation interventions delivered early in the school year can prevent downward cycles of psychological threat and poor performance among ethnic minorities (p. 80). So before you attempt at these wise interventions you have to make sure you can apply these “Do’s” and “Don’ts” in order for it to be successful.

When thinking about a Wise Intervention that is most similar to our project, we wanted to use one that expanded learning (preferably students) using a unique strategy or action, or a Wise Intervention that took a standard of learning and discipline that was actually negative towards student learning. It is important to understand the negatives of a discipline learning style like D.A.R.E, so we can emphasise the positives as opposed to interventions and teaching styles. Majority of students that have gone through the basic public school system have heard of systems like D.A.R.E. and other scared straight programs. D.A.R.E., which stands for Drug Abuse Resistance Education, has a mission to work with students across the United States and “[give] kids the skills they need to avoid involvement in drugs, gangs, and violence” (About D.A.R.E., 2020). The conclusion is that D.A.R.E. programs are actually ineffective, and can turn out to be harmful.

So, how could D.A.R.E. programs help teach us what could be effective in learning programs, the answer is changing the mindset intervention. The entire idea of programs like D.A.R.E. are surrounded by negative connotation and amotivational thinking for young and developed minds. “People constantly try new ways to motivate children or to change adults’ behavior (e.g., encouraging smokers to quit). The question is not whether to deliver psychological interventions but how to do it well— effectively and responsibly” (Walton, G. M., & Wilson, T. D, 2018). Ways of making the program “effective and responsible” come from the lessons and motives being installed. In D.A.R.E’s example their messages of “Kids, don’t to drugs” is not effective in their learning behavior, it is the same as telling a 3rd grade math student that they are “a natural at math”, all that does is burn the motivation of the student because it is telling them their skillset is fixed. With this amotivational psychological persuasion, D.A.R.E. programs will never have success on young psychological minds. However, if D.A.R.E. programs use open minded thinking and alternative behaviors for young kids to admire and follow, D.A.R.E. programs will find that their students are motivated and will have more success.

An example of growth mind-set interventions that is most like our work is the “Growth mind-set of intelligence” intervention (Blackwell, L. A., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S, 2007). In this intervention, eighth-grade students learned in their classroom workshops that “intelligence is malleable and can grow like a muscle with hard work and help from others”, as well as learning about “ the relationship between brain regions and brain functions” (Blackwell, L. A., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S, 2007). With such an influential topic for such a young classroom, it is extremely important that students have a growth mind-set and “interpret academic challenges as opportunities to learn, not as evidence of fixed inability, and respond by trying harder, not by giving up”(Blackwell, L. A., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S, 2007). This is what worked the most in terms of our project. We emphasise that having different learning styles is not to “box” students into a certain category of learning, but allow them to understand that these different aspects of learning can help them and their ability to learn. For example, telling a student that they are “better visual learners” doesn’t just interpret positive visual learning for the student, but it also tells that student that they are not very good kinesthetic learners, which puts them into an amotivational style of learning, like D.A.R.E. programs. As a result of this intervention, “the control group [in the 8th grade classroom] continued to show a decline in math grades, whereas the treatment group showed a rebound (Blackwell, L. A., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S, 2007).

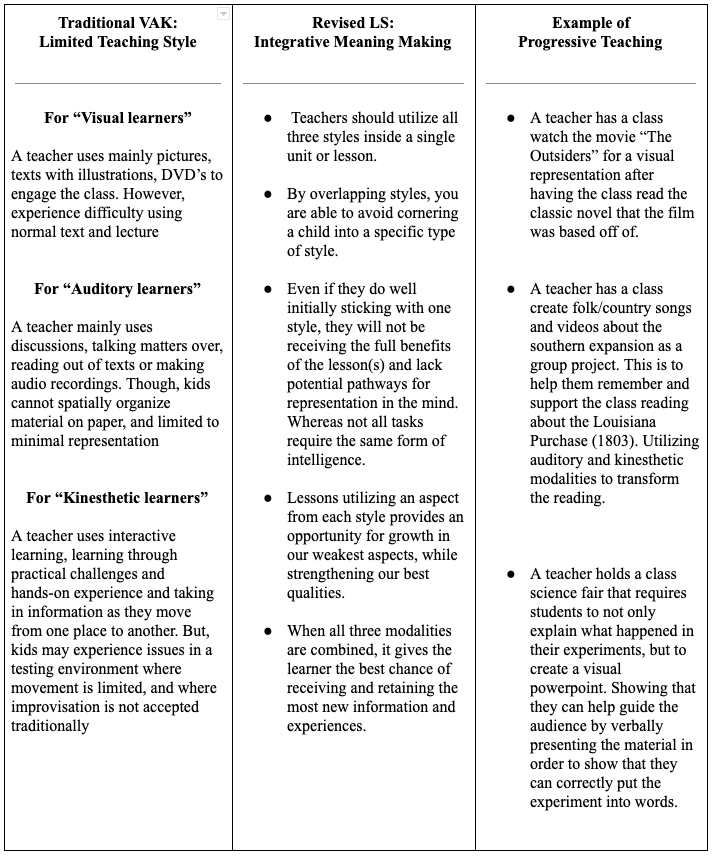

As a teacher, understanding how to portray affective cognitive learning is very important and can be extremely detrimental if taught wrongly. As we learn from programs such as D.A.R.E, negative connotations and single categorical teaching creates the learning amotivational, which in retrospect does not allow the “learning muscle to develop”. As shown with the “Growth mind-set of intelligence” intervention, it is extremely important to create a learning environment that allows all three froms of VAK learning styles to be implemented, without influencing one or the other, This is demonstrated in our Wise intervention below as a “combined progressive teaching style” which accumulates everything we learned about what was wrong with standard teaching programs , and what was positive about teaching programs like growth mind-set of intelligence. This allowed us to understand how to effectively teach via learning styles, as well as how to train the correct “muscles” when it comes to learning.