7 Building a Framework

Critical pedagogy in action

Mary Mathis Burnett

For instructional designers, the work can sometimes feel like a series of cleanup steps to better position the course content for learners or to ease the burden of instructors. Caught in powerful systems of grading, academic integrity, and institutional hierarchy, we can find ourselves focused on consistency and efficiency rather than supporting learning as the primary goal. As an instructional designer in higher education, I am certainly guilty of missing opportunities to advocate for students in order to meet a deadline or institutional expectation, so I started asking myself what would happen if we allow the mess instead? What if we transformed our thinking into imagining the possibilities of pedagogy instead of reshaping and repurposing what already is? This question underwrote my goal of improving the equity, accessibility, inclusivity, and quality of instruction for online courses by enhancing the overall approachability and encouraging the broad application of critical pedagogy by faculty and instructional designers.

Critical pedagogy works to stop the ongoing damage done within the systems already at play by empowering all participants to bring about the necessary social changes they see are needed. It causes us to examine the context of the classroom, the perspectives included, excluded, and prioritized, the assumptions active in the room, and the power and authority of the people and systems within the classroom and institution (Freire, 1985). In higher education, where professional teaching practice is commonly ignored or undervalued, it is potentially unfair to ask faculty to apply critical pedagogy without support. In the interest of fostering more empowering pedagogy and instructional design, I worked to create support in the form of the Application Framework for Critical Pedagogy (AFCP).

As part of my doctoral journey, I designed a research study that would both examine the process of creation for a critical pedagogy framework and to describe the framework itself as created. In this chapter, I will discuss my research by describing the background and theory, the process of creation, the framework itself, and conclude with implications to the fields of teaching and instructional design.

Background and Theory

As a concept, pedagogy has taken various forms over many centuries, having been used in ancient Greece to describe the nurturing of the whole person independent from the teaching of content (Smith, 2019) and defined simply as, “the art, occupation, or practice of teaching,” as in the Oxford English Dictionary (2020). This leaves much room to debate, disagree, practice, theorize, and apply a personal style (Smith, 2019). My training as an instructional designer centered around content, strategies, and grades, and so did my pedagogy. Encountering critical pedagogy and actor-network theory highlighted distinct gaps in a pedagogy like mine. Tending to those gaps fundamentally changed my pedagogical perspective, so my approach now requires an acknowledgement of the whole person, their agency and full humanity, their learning goals, and their ability to interact well in the world where they will encounter similar power dynamics. This acknowledgement is a step toward expanding the traditional boundaries of higher education which can be oppressive to the natural freedoms of students while also a step toward undermining the ties of higher education to the status quo.

Critical pedagogy suggests that we cannot ignore the ways we uphold white supremacy and nationalism, heteronormativity, and the patriarchy, while actor-network theory suggests that we cannot ignore the ways we establish truth and knowledge when they disenfranchise or dismiss individuals. We owe it to students to model paths to solutions, and we must involve students in the process of their own education, even if they are uncomfortable with that. I argue that critical pedagogy and actor-network theory are able to do just that and that they work together symbiotically to accomplish it.

Paulo Freire (1985), who is widely credited with founding critical pedagogy, insisted there is no neutral stance related to the freeing of the oppressed. He wrote that absolving ourselves of the responsibility to act in the conflict between the powerful and the oppressed is not neutral but an act on the side of the powerful (Freire, 1985). Without sound pedagogy, teaching becomes transactional. Technologists become investigators. Teachers become judges and enforcers. Retention and completion become synonymous with quality. Along the way, the significance of student learning is reduced, and we end up justifying Freire’s concerns, particularly when it comes to minoritized students.

By the time they enter college, students understand textbooks as authority, professors as experts in the best cases (Law, 2009) and as judges of their competence in the worst, grades as the arbiters of success or failure or self-worth (Crocker, 2002), and that they must learn the right things to say or write to prove their worthiness for the grade (Illich, 1970). We are all conditioned by a system that elevates and honors knowledge without questioning how it came to be or whether it is possible for the system to operate another way. Critical pedagogy encourages us to question the status quo, looking critically at the way things are and who has the power, as opposed to the transactional model which inspires students to passively receive information.

We continue to see damage done by the white, cis-heteropatriarchy and by unchecked dominant culture on those who are oppressed and marginalized (Shah, N.D.). We watch, in real time, the destruction of voting rights for minoritized Americans, the carceral violence perpetrated and perpetuated against Black and African Americans while white owners of legal marijuana dispensaries make record profits, the overvaluation of power, aggression, and greed while belittling empathy and foresight, and the overrepresentation of white men in academia, politics, and government while the voices of women and minoritized individuals are suppressed (Leao, 2019; Rahman, 2021). Unless consciously disrupted, this status quo and the damage done by the systems are manifested in the classroom. We can see this clearly in higher education degree granting numbers wherein, “if black and Hispanic graduates earned each degree type at the same rate as their white peers, more than 1 million more would have earned a bachelor’s degree” between 2013 and 2015 (Libassi, 2018, para. 3).

The system of American higher education has become heavily commodified, seeking continuous enrollment growth and promoting graduation rates as the primary measure of success. Technology to prevent cheating and surveil students controls the market and underscores the dominant culture of grades and power over humans and learning. Sean Michael Morris (2021) discussed societal acculturation to grades and what it means for students: that they attend college to succeed rather than to learn and that success is determined by grades. The power and authority of grades can overwhelm even the most well-intended teaching approach, especially when instructors across the industry have little or no pedagogical training. Ann Beck (2005) writes that schools also participate in the perpetuation of power relationships by legitimizing knowledge and practice that serve the interests of the dominant group and that critical pedagogy offers the means to equalize the classroom environment such that students can practice active citizenship, confronting and resisting the ways textbooks and discourses sustain social inequalities and injustices.

If we are to examine and challenge the power and authority in the classroom, we must also investigate the rest of our pedagogy including who holds power in each of the relationships involved. In transactional classrooms, power is necessarily in the hands of the educator and unreachable by students. It is more than the educators’ power we must be aware of, though, as entire groups of people are marginalized and oppressed by the larger dominant culture. The classroom is not, nor are students, isolated from these social powers and oppressions, and educators must either uphold or upend them. Critical pedagogy wants educators to determine for themselves the future of their pedagogy.

Similarly, actor-network theory (ANT) makes three specific arguments:

- Knowledge is not “coherent, transcendent, generalisable, unproblematic, or inherently powerful” (Fenwick and Edwards, 2014, p. 47),

- The object or agent is not separate from the idea of it and can be realized in multiple forms, and

- Knowledge and truth are not inherent properties but are, instead, ascribed by a network through a process (Latour, 1988; Fountain, 1999; Law, 2009; Fenwick and Edwards, 2014; Sarauw, 2016). In higher education where content matters most, ANT would question why, how, and who? Where faculty wield power over students, ANT would want to know why, how, and who?

Where ANT focuses its attention, however, is not on the knowledge itself but on agency and power, mechanisms to authorize knowledge, distribution within the network, and its purpose and effect. Fenwick and Edwards (2016) note that higher education tends to place high importance on knowledge committees, quantifiable standards, competition, and outcomes which creates and activates different assumptions than might be found outside of higher education about what knowledge is legitimate (p. 44). We find trouble in failing to realize the difference between a material or knowledge object held in different perspectives and one that manifests differently in different contexts. This idea left me with two questions: What if we let our differences coexist? What if differences were not reconciled with what we each experience but accepted as they are?

Granovetter (1973, 1983) focused on the usefulness of weak network ties that are sometimes disregarded in research in favor of much stronger relationship ties; however, he also argued that strong ties are not actually a strength for an organization. Because of the high level of similarity implied by their strength, they tend to limit the experience and exposure of individuals (Granovetter, 1983; Kezar, 2014; Liu et al., 2017). Weak ties, on the other hand, bring diversity of thought and experience by increasing access to varied information. While strength of connection is important for network cohesion, it can undermine a network’s ability to change and make progress and limit an individual’s cognitive flexibility if not bolstered by weak ties (Granovetter, 1983).

Citing two ethnographic studies by Stack (1974) and Lomnitz (1977), Granovetter (1983) highlights the necessity of strong ties for poor, marginalized, and insecure populations. They have fewer alternatives in the form of weak ties, relying on their close relationships for survival in times of food and housing insecurity, while the wealthy are privileged to be able to explore their weak ties to transform their worlds without concern for their survival. As the network strengthens its ties and minimizes its weak ties, it also reduces its ability to access information born outside of the network (Granovetter, 1973; Granovetter, 1983; Kezar, 2014; Liu et al., 2017), and therefore, the status quo is reinforced.

Critical pedagogy stands in the margins demanding an end to oppression, asking to be deployed on behalf of the oppressed rather than simply asking the oppressors to change. It promotes reminding marginalized persons of the power they already have, so they are able to speak in their voices and stand for themselves. Freire called for engaged praxis rather than limiting ourselves to theoretical rhetoric, and that is where this study begins. Alongside critical pedagogy, social network theory examines all players involved in a given group, connections to each other and the outside world, and the flow of knowledge, power, and material, while actor-network theory equalizes power and examines all players, their complex social lives and experiences, and the way knowledge is accepted and power given.

Creating the Framework

As an instructional designer in a large, public, research university, I work with around 430 faculty across Watts College of Public Service and Community Solutions, many of whom teach online and face-to-face. My purpose in setting up this project was to improve the pedagogical experience of faculty and instructional designers in the college. With access to training resources and support but no requirement to participate, faculty engagement is low across the board. Gardiner (2005) wrote about this as a pervasive higher education problem.

“Higher education continues its longstanding custom of investing little in the preparation of its teachers for their work as educators…Where faculty and staff professional development programs exist, more often than not they are weak, participation in them is voluntary, and they are given only desultory moral and financial support by senior administrators” (Gardiner, 2005, p. 12).

Courses in this college place a priority on traditional lectures, papers, and presentations and generally lack critical pedagogical application. We aimed both to challenge faculty to move beyond papers and presentations and to improve the use of critical pedagogy in online courses.

Applying tenets of critical pedagogy, actor-network theory (ANT), and social network theory (SNT), I was interested in how such a framework would be created, identifying the social, cultural, environmental, and relational factors which influence the process, and encouraging broader use of critical pedagogy. I also hoped to examine and understand the nature of power and privilege at work in the college and to create a leveling effect whereby all voices could have equal priority. It was in the active, intentional deployment of equitable practices where critical pedagogy and actor-network theory complemented each other, in two main ways: 1) ANT joined critical pedagogy to explicitly apply equal priority to the voices involved, and 2) ANT connected with social network theory to review, explore, and describe the social and relational influences involved in creating the Application Framework for Critical Pedagogy (AFCP).

I used Participatory Action Research (PAR) as the foundation for the project which asserts that mutual understanding and collaboration lay the path toward new knowledge and allow the researchers and participants to share ownership of the research project and determinations of its success or failure (Grant et al., 2008, p. 590). Influenced early by Freire’s idea of conscientization, PAR came to represent the empowerment of marginalized people rather than using an outsider as savior, the idea that they are able to design action based on their own critical analysis (Coughlin and Brydon-Miller, 2014), and the aims to support their ability to do so (Grant et al., 2008). The principles of critical pedagogy and participatory action research suggest that student-, faculty-, and staff-stakeholders must be included in processes that will affect them, and actor-network theory provides the means to make those efforts successful.

The first step for us was to gather information from the community members which included students, faculty, and staff across the college. We needed to understand how familiar they were with critical pedagogy, how comfortable they were with the language and application of critical pedagogy, whether their comfort level changed depending on whether they were teaching face-to-face or online, and what they actually wanted from the classroom. Given the subjective nature of critical pedagogy and the personal nature of pedagogy in general, the priorities of the community members were at the top of the list of things any framework should provide. I used an online survey to retrieve those answers and followed the survey with interviews of those who volunteered. I was able to put together a diverse team representing each of the four schools in the college: School of Social Work, School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, School of Public Affairs, and School of Community Resources and Development.

I created a Slack workspace so those on the team could connect via online chat to focus their list of priorities so we had an agreed upon starting point. The Slack workspace was set up to neutralize many of the known power dynamics by operating in small, anonymized groups so the discussion could move forward without their knowledge of each other’s gender, race, tenure status, or status as faculty, staff, or student. I’m including the discussion of Slack, despite that it did not go well for this team, because I believe anonymizing interactions at some point in the process of creating a framework like this is important to mitigate the current power and social dynamics if possible. Because the Slack discussions yielded so little information, I had the team rank the importance of characteristics of critical pedagogy that I pulled from the early interviews and survey data.

During the active creation process, the committee defined evaluation, the practice of critical pedagogy, the expectations and layout of the framework, and the way the framework would be evaluated and implemented. The committee was composed of 12 individuals, including myself, from all four schools in the college as faculty and staff. Notably, students were missing from these discussions, though two students had participated in the interviews and three others completed the survey. While the hope had been to have students involved throughout the build sessions so they could carry their own message, the addition of actor-network theory created a path for me to ensure their thoughts were represented in the build sessions after they stopped participating. Additionally, four of the faculty and staff present in the meetings also identified as students and were able to bring their experiences into the discussions, while others included feedback and information they had received from students in their courses.

Early on, it became clear that a simple visual framework or checklist would not accomplish what we had set out to create. Folks in the meetings shared the ways they work, characteristics of effective tools, and how they would or would not be able to use this framework as we discussed the language and purpose of the tool. In addition, the build team focused heavily on the priorities, outcomes, and structure of the tool and decided to employ a question-based format to encourage reviewers to decide for themselves how well the course applied critical pedagogy. This would also allow for professional growth through the process and provide scaffolded support for those faculty who need basic pedagogical training and those who might apply more advanced pedagogies. The framework needed to be somewhat self-contained, shareable, offer results on a continuum along with resources to match, require and encourage critical self-reflection on the part of the faculty, and not let them “off the hook” by allowing them to feel exempt from the equity, ethics, and social justice issues at hand.

The Application Framework for Critical Pedagogy

Considering all of the expressed needs, I built the Application Framework for Critical Pedagogy using Twine, an online browser-based system designed for interactive story-telling. The tool uses a primarily text structure, is open-source, and available to anyone with internet access. Twine includes rich support resources and is useful even for those with no technical expertise or background. This tool allowed me to build solutions quickly and to create a branched decision-making functionality where users could determine their own starting and ending points.

After an initial pass at creating the framework based on the discussion from the first build meeting, I brought it to the committee for feedback. There was general approval for the format, layout, structure, and direction, but there was much discussion about particular word choices made for certain sections of the framework. The word power, for instance, garnered some specific attention during the discussion.

P2: Is anyone concerned with faculty looking at the word student power and frowning? I only say that because I think we need to empower, right? I don’t want someone to- those that aren’t invested in this process, we need to capture, and I don’t want them to get the wrong idea of what the goal is here. It isn’t for the student to take power over the class. It’s to empower them to feel engaged.

P1: The term I use in my class is; you take ownership of your learning. You take ownership of your project. I could definitely, [Participant 2], you’re in [School of Criminology and Criminal Justice] like me, us [criminal justice] folks don’t like anything that’s going to- the power thing won’t go well with the majority of our faculty.

Participant 9 also cautioned the group against contributing unexpectedly to the marginalization of already marginalized students.

So there’s been cases where, you know, we have used peer evaluations as part of the scoring. And, you know, we will take the workgroup and have them evaluate each other. So I do agree that peer evaluations and peer feedback is critical in this shared power environment and it’s a great learning tool. However, I’ve seen that marginalization has occurred in those situations as well, to further oppress or marginalize those that are [already] marginalized, so that…was [an] unexpected consequence. I think, I know that was my blind spot, but so how we weight that is important.

The final build session began with an overview of the final draft of the framework, displayed in Figures 1-5, for review by participants. More than anything else, this session involved tying up some of the loose ends such as deciding how we would pilot test the final framework and what adjustments to the structure or function were necessary. After the discussion of the word power in the second, I replaced it with the word autonomy to accommodate the group’s feelings about the implied construct of power. Power dynamics being an essential part of any critical pedagogy review, the discussion was important to frame the concept in an appropriate way for a diverse group of faculty. Interestingly, those who expressed an initial reaction to the word power were unbothered by autonomy, but those unbothered by power reacted strongly to autonomy.

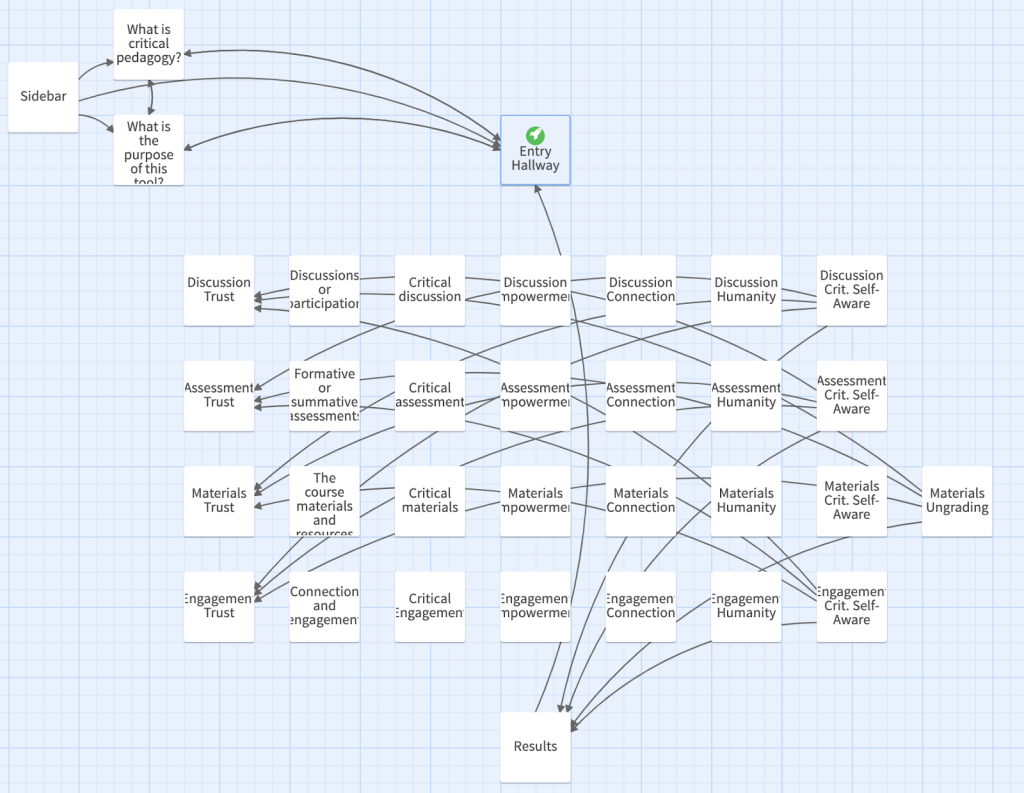

Figure 1 shows the overall structure of the framework which had become more streamlined and focused since the first draft. It includes the various pathways a reviewer might take in the process, including a sidebar with helpful information about critical pedagogy and the tool itself in addition to the review paths selected by the reviewer. The build team decided on four common categories in use with online courses (i.e. Discussions, Assessments, Materials, and Engagement) and seven characteristics of critical pedagogy with which to review courses (i.e. Trust Building, Critical Thinking, Empowerment, Connection, Human Experience, Critical Self-Awareness, and Ungrading [only for the Materials category]). The results page processes the decisions made by the reviewers to provide resources that may assist in improving the application of critical pedagogy for the specific course reviewed.

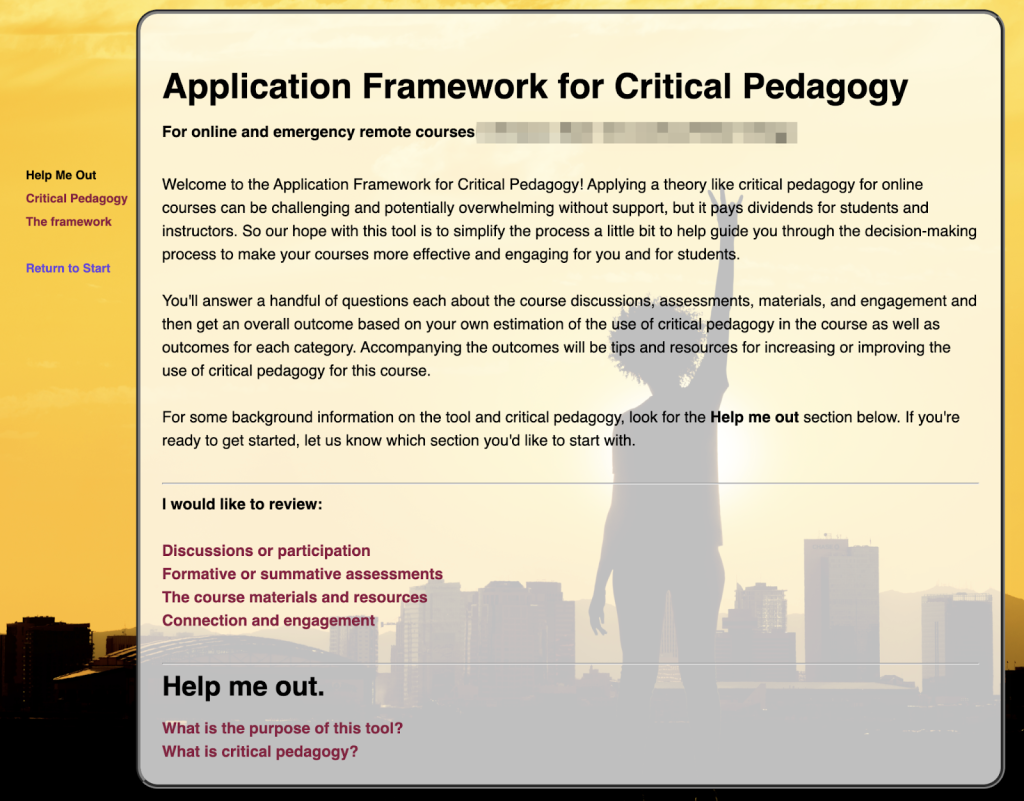

Figure 2 shows the initial landing page for reviewers which operates as a welcome, an introduction, and the navigational starting point for each section of the framework. From here, reviewers determine their own needs and navigate accordingly to find help, critical pedagogy resources, and sections for review.

Figure 3 shows the What Is the Purpose of this Tool? page. This page offers a brief description of the tool, its intention and design, the same critical pedagogy resources section as on the starting page, and a return to the starting page from which reviewers are able to navigate.

Figure 4 shows the What is Critical Pedagogy? page which houses a handful of curated video resources which focus on different aspects and perspectives of critical pedagogy to provide context for reviewers who are unfamiliar with the theory.

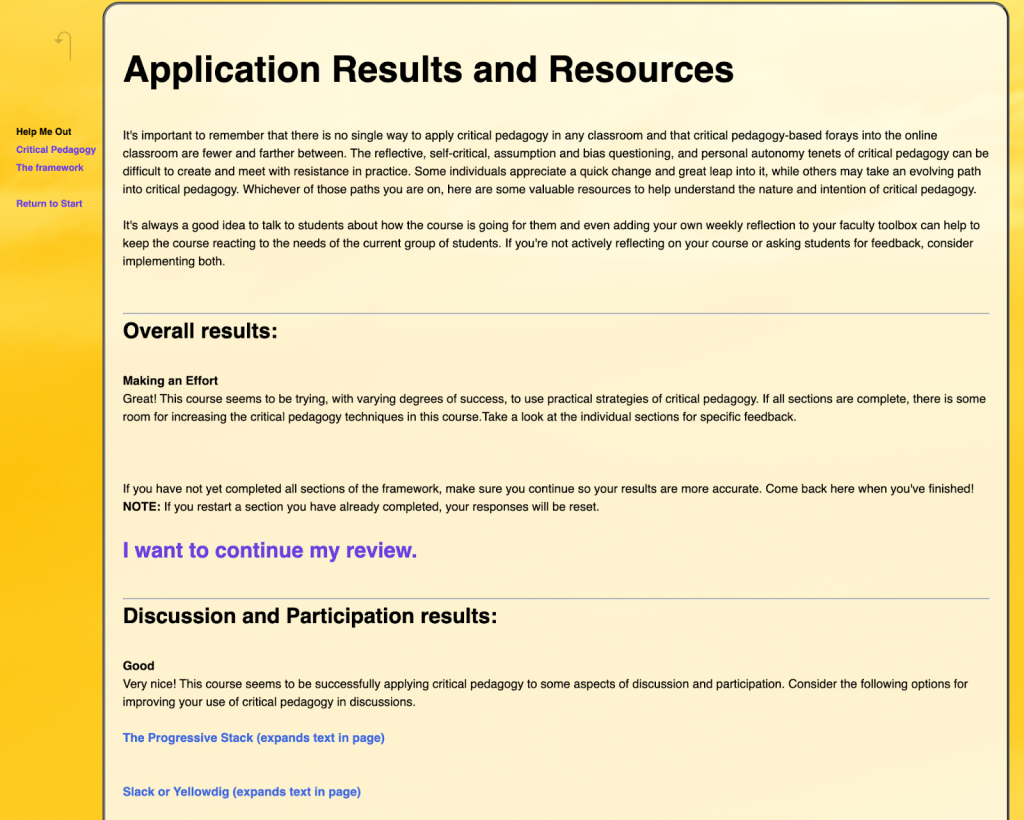

Figure 5 shows an example of the Results page, in this case having calculated only the Discussion and Participation section. Reviewers have the opportunity to decide to continue their review of the remaining sections or to explore the resources offered in the discussion results.

With any luck, the AFCP will have no final state, but in its final form for our project, the framework asks reviewers for their own assessment of a course’s use of each characteristic of critical pedagogy within four categories: discussions, assessments, materials, and engagement. The AFCP does not offer scores but does use the reviewers’ answers to estimate the course’s success in applying critical pedagogy (i.e. Exemplary, Making an Effort, Missing the Mark, and Not Trying). Based on that estimation, it offers resources for the user to apply or adapt for their own purposes, leading with the philosophy of critical pedagogy rather than a prescriptive to-do list. It bears pointing out that the rating system here may be akin to grading, because we were working within the limitations of Twine, my experience with Twine, and dissertation time constraints. In future iterations, I hope to find a better way to match appropriate resources with reviewers’ answers.

We had eight Watts College community members who did not participate in the build sessions to pilot test the framework. After using the AFCP to determine how well a course applied critical pedagogy, these participants completed an online survey to report their results and impressions. Here, I was looking for whether they agreed with the framework results and what they thought of the overall experience. Participants’ reported their experience with the framework with questions about their familiarity with critical pedagogy, aptness of the framework’s structure and content, likelihood of applying critical pedagogy in the future, accuracy of results, and ease of use.

This version of the Application Framework for Critical Pedagogy does meet many of the expressed needs of the committee with its flexible and self-directed function, offer of basic critical pedagogy and other recommended resources, and language encouraging users to challenge themselves, their thinking, and the status quo. The AFCP does not yet meet every need expressed by the participants; however, with the flexibility of format, it could easily have additional pedagogical resources installed, a more visually diverse interface, and the ability to be used in more discrete and nuanced ways.

Implications for Instructional Design and Pedagogy

As instructional designers, we can exercise some influence over the direction a course takes and the practices necessary to run it well, and that influence can vary by institution, program, course, and even faculty member. Part of the instructional designer’s job is to ensure the instructional soundness of a course which requires an eye on the student and faculty experiences, pedagogical choices, programmatic and course-level outcomes and priorities, and technology functionality. The AFCP (https://critpedframework.com) can be a tool for instructional designers to use as part of their quality assurance process or as a teaching tool for faculty with whom they work.

One of the stated requirements for the AFCP was to promote good pedagogy more generally, so instructional designers can use the framework to proactively identify principles and practices of pedagogy that could be applied to individual courses in addition to promoting the ideals of critical pedagogy. The framework is designed as a thinking tool which can promote the type of critical thinking about courses that the courses themselves are wont to produce.

While the framework has not been distilled to simply good practice pedagogy, one of the primary goals was to allow for faculty to evolve into the use of critical pedagogy. In practice, critical pedagogy requires a certain readiness to self-reflect in a critical way, so asking a new faculty member with no pedagogical training to do this from the beginning is unfair both to the instructor and to their students. To encourage professional growth, the committee curated resources to meet faculty wherever they are in their journey. Because the framework is designed as a reflection and thinking tool, it can also be used as an opportunity for faculty to hear feedback they might otherwise have rejected.

This project connected a team of people from diverse backgrounds and sometimes opposing perspectives to distill the principles and practices of critical pedagogy into an accessible format without avoiding or reveling in its political foundation. Research for the framework also continues with an expanded audience outside the university. The AFCP is a step toward change for those faculty and instructional designers who want to participate in social changes but may not know where to begin in their own context. In this functional framework, at least, we have provided an accessible means for folks to encounter critical pedagogy, a meaningful mechanism to evaluate performance, and an opportunity to enhance learning by exposing power dynamics and encouraging self-reflection and self-advocacy. Future researchers, faculty, staff, and students are encouraged to use both the process and tool for their own contexts and purposes.

References

Beer, S. (2001). What is cybernetics? [Address]. Kybernetes 31(2). doi: 10.1108/03684920210417283. https://web.archive.org/web/20160426001835/http://www.nickgreen.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk/beerWhatisCybernetics.pdf

Berger, D. (2021, January 11). The multiple layers of the carceral state. Black Perspectives. https://www.aaihs.org/the-multiple-layers-of-the-carceral-state/

Caldwell, J. (1970, April 29). Proceedings from American Council Fellows closing seminar: The role of higher education in social change [keynote]. Raleigh, NC. https://soh.omeka.chass.ncsu.edu/items/show/33094

Coghlan, D., & Brydon-Miller, M. (2014). Participatory action research. The SAGE encyclopedia of action research (Vols. 1-2). Sage Publications Ltd. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446294406

Crocker, J. (2002). The cost of seeking self-esteem. Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 597-615.

Dewey, J. (1925). Experience and nature. George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

Fenwick, T. & Edwards, R. (2014). Networks of knowledge, matters of learning, and criticality in higher education. Higher Education, 67, 35-50.

Fountain, R.M. (1999). Socio-scientific issues viz actor network theory. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 31(3), 339-358.

Gamoran, A. (2018, May 18). The future of higher education is social impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_future_of_higher_education_is_social_impact

Gardiner, L.F. (2005). Transforming the environment for learning: A crisis of quality. In S. Chadwick-Blossey (Ed.), To improve the academy: Resources for faculty, instructional and organizational development (Vol.23). Anker Publishing Company. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download;jsessionid=C20901408F7B921A8C094ACCB7022D13?doi=10.1.1.520.680&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Ginder, S. (2014). Enrollment in distance education courses, by state: Fall 2012. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2014023

Giroux, H.A. (2017). Critical theory and educational practice. In Darder, A., Torres, R.D., Baltadano, M.P. (eds.) The critical pedagogy reader, (3rd ed.). (31-55). Routledge.

Granovetter, M.S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380.

Granovetter, M.S. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociological Theory, 1, 201-233.

Grant, J., Nelson, G. & Mitchell, T. (2008). Negotiating the challenges of participatory action research: relationships, power, participation, change and credibility. In Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. The SAGE handbook of action research (pp. 588-601). Sage Publications Ltd. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781848607934

Greene, M. (2007). Countering indifference – The role of the arts. https://maxinegreene.org/uploads/library/countering_i.pdf

Heath, C., Hindmarsh, J., & Luff, P. (2010). Video in qualitative research. Sage Publications, Inc. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781526435385

Hidebrand, David (2018, November 1). John Dewey. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/dewey/

Illich, I. (1970). Deschooling society [Kindle for iPhone version]. KKien Publishing International.

Kemmis, S. (2008). Critical theory and participatory action research. In Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. The SAGE handbook of action research (pp. 121-138). Sage Publications Ltd. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781848607934

Kezar, A. (2014). Higher education change and social networks: A review of research. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(1), 91-125.

Kim, J. (2019). The conversation about scaling high-quality/low-cost graduate online education. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/technology-and-learning/conversation-about-scaling-high-qualitylow-cost-graduate-online

Latour, B. (1988). Science in action. Harvard University Press.

Law, J. (2009). Actor network theory and material semiotics. In B.S. Turner (ed.), Blackwell companions to sociology: The new blackwell companion to social theory. (pp. 141-158). Wiley-Blackwell.

Leão, G. (2019, August 20). Understanding the rage of white male supremacy: An interview with Lisa Wade, PhD. WMC Women Under Siege. https://womensmediacenter.com/women-under-siege/understanding-the-rage-of-white-male-supremacy-an-interview-with-lisa-wade-phd

Libassi, C.J. (2018, May 23). The neglected college race gap: Racial disparities among college completers. American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/neglected-college-race-gap-racial-disparities-among-college-completers/

Liu, W., Sidhu, A., Beacom, A.M., & Valente, T.W. (2017). Social network theory. In Rossler, P. (ed.) The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316250457_Social_Network_Theory

Mathis Burnett, M. (2020). Building a framework: Critical pedagogy in action research [Doctoral dissertation, Arizona State University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Morris, S.M. (2021, June 9). When we talk about grades, we are talking about people [keynote presentation]. #RealCollege Virtual Journey, Philadelphia, PA. https://www.seanmichaelmorris.com/when-we-talk-about-grading-we-are-talking-about-people/

Narayanan, A. [random_walker]. (2019, October 11). My university just announced that it’s dumping Blackboard, and there was much rejoicing. Why is Blackboard universally reviled? There’s a standard story of why “enterprise software” sucks. If you’ll bear with me, I think this is best appreciated by talking about… baby clothes! [Twitter moment]. https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1182635589604171776.html

Pedagogy, n. (2020). Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.oed.com/viewdictionaryentry/Entry/139520

Rahmud, M. (2021, March 8). We are all victims of a patriarchal society: Some just suffer more than others. Cordaid. https://www.cordaid.org/en/news/we-are-all-victims-of-a-patriarchal-society/

Sarauw, L.L. (2016). Co-creating higher education reform with actor-network theory: Experiences from involving a variety of actors in the processes of knowledge creation. Theory and Methods in Higher Education Research, 2, 177-198.

Smith, M.K. (2019). What is pedagogy?. The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. https://infed.org/mobi/what-is-pedagogy/

Swantz, M. (2008). Participatory action research as practice. In Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. The SAGE handbook of action research (pp. 31-48). Sage Publications Ltd https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781848607934

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2018). Fast facts: Distance learning. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=80

Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical investigations. Basil Blackwell Ltd.