5 Indigenizing Design for Online Learning in Indigenous Teacher Education

Johanna Sam; Jan Hare; Cynthia Nicol; and LeAnne Petherick

How do you bring Indigenous knowledges into learning management systems (LMS)? How do you weave Indigenous perspectives in the course design while using a LMS that can be seen as dominant/Eurocentric? Indigenous Teacher Education Programs (ITEPs) play a critical role in preparing Indigenous teacher candidates (ITCs) to serve Indigenous learners, schools, and communities. While ITEPs may allow Indigenous students to remain in their communities for their teacher education programming, ITEPs are generally part of mainstream teacher education. Critiques of teacher education have established how classrooms operate as colonized spaces (Cote-Meek, 2014). As a result, dominant/Eurocentric theories and practices of teacher education curriculum tend to marginalize ITCs’ knowledge and experience in coursework (Brayboy & Maughn, 2009). ITEPs need to innovate to create distinctive curriculum and pedagogies that prepare ITCs for blended classrooms (e.g., online and in person teaching) and Indigenous communities (Hare, 2021).

As Indigenous and ally teacher educators and scholars, we come together to promote an Indigenizing design approach for teacher education curriculum that centers Indigenous perspectives, histories, worldviews, and pedagogies in online learning environments in respectful and productive ways. Central to our work is validating ITCs’ experiences as legitimate knowledge sources in coursework.

While there is growing scholarship that describes ITCs learning from Indigenous knowledges (Brayboy & Maughan, 2009; Garcia & Shirley, 2013; Whitinui, Rodriguez de France, & McIvor, 2018), we situate our collaborative curriculum design process within new multi-modalities that bring Indigenous knowledges and pedagogies into online learning spaces. We share pedagogical principles guiding Indigenization of a set of courses that are part of the curriculum in the professional certification year of the Bachelor of Education program for ITCs in NITEP – the Faculty of Education’s Indigenous Teacher Education Program at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in western Canada. We offer personal and professional insights on the application of these principles, highlighting the Indigenizing design process, providing examples of how Indigenous knowledges and pedagogies operate within and beyond the digital boundaries of synchronous and asynchronous coursework, and reflections on student engagement and learning.

In line with Indigenous protocols to knowledge, we situate ourselves in relationship to the matters on which we write. We are a collective of scholar-educators who work in a large teacher education program in western Canada. Two of us are Indigenous. Johanna is a proud citizen of Tŝilhqot’in Nation in north-central British Columbia. Johanna’s research and teaching takes a strength-based approach for exploring digital spaces and wellbeing among youth and Indigenous communities. Jan is an Anishinaabekwe from the M’Chigeeng First Nation in northern Ontario. Her teaching and research are concerned with how Indigenous and ally teachers respond to Indigenous knowledges and pedagogies in their classroom practices. In her role as Director of NITEP, she has sought to transform mainstream teacher education programming to be more responsive to ITCs. LeAnne is a fourth-generation settler scholar with Scottish and English heritage, who grew up on the traditional Lands of the Anishinabewki, Mississauga, and Wendake-Niowentsio. Her teaching and research are grounded in social justice issues in Physical Education, Health Education, Sport and Teacher Education. She is committed to social justice issues as a strategy for shifting the dialogue, practice, and experience of people through human movement practice. Cynthia is a seventh-generation settler Canadian of German and English ancestry raised on the Ktunaxa (Kootenay) territory in southern British Columbia and learned to teach mathematics on Haida Gwaii in BC’s Pacific northwest coast. Cynthia’s research and teaching focuses on working with communities and teachers bringing together mathematics, community, culture, and place.

Indigenizing Learning Design

For us, Indigenizing design is not about replacing the Eurocentric curriculum of teacher education with Indigenous content. Rather, it is about embedding Indigenous perspectives and histories across critical dimensions of course design that includes objectives, learning activities, assessments, and pedagogies to form a “plan for learning” (Thijs & van den Akker, 2009). It is a process that is responsive to local lands, languages, traditions, and knowledges where ITCs live and learn. It reflects a commitment to naturalizing Indigenous ways of knowing within learning design. Pete, Schneider, and O’Reilly (2013) suggest Indigenizing is about resistance to the colonizing tendency to erase Indigenous people and the persistence of Indigenous ways of knowing. Grafton and Melancon (2020) explain Indigenization as “a process of resurgence, a recentring of precolonial and colonial ways of knowing and being that never ceased to exist despite colonial structures and process and their attempts to assimilation and erasure” (p. 142). Our Indigenizing frame of reference focuses on online teaching and learning that is inclusive of Indigenous knowledges and pedagogies in ways that empower ITCs and the school and communities they serve.

Digital environments are not neutral spaces, nor should they be considered landless (Geartner, 2016). Morford and Ansloos (2021) tell us that “with the rise of computer-based technology, settler colonialism has seeped into the cyber-realm. The Internet has become another space and place where the violence and normalization of colonization are perpetuated” (p. 295). While efforts to represent Indigenous knowledges in online spaces risks appropriation, misrepresentation, or commodification, Wemigwans (2018) believes in the transformative potential of Indigenous knowledges in digital spaces to contribute to Indigenous healing and resurgence when Indigenous communities control information that is generated and shared online. Similarly, Article 14 of the United Nations of Declaration of Rights for Indigenous Peoples, indicates that “Indigenous peoples have the right to establish and control their educational systems.” With respect to providing education in a manner appropriate to Indigenous teaching and learning, we focus on the ways Indigenous knowledges and pedagogies can be organized, mediated, and practiced within and beyond the online learning space to promoteIndigenous values in virtual environments (de Haan, 2018).

Indigenous Teacher Education: A Context for Digital Design

NITEP is a well-established Indigenous teacher education program that prepares ITCs for education roles in classrooms, schools, and communities. It offers community-based programming in remote, First Nations, and rural areas of the province of British Columbia, Canada, allowing ITCs to remain at a local field center for the first 3 to 4 years of the program before transitioning to UBC’s Vancouver urban campus to complete their professional certification year of their 5-year concurrent Bachelor of Education degree. This move to campus results in student attrition and impacts on program completion due to family and community commitments, financial barriers, and cultural priorities experienced by ITCs. Review of research suggests that students prefer community-based approaches to teacher education, whereby they can become certified teachers without having to leave their home communities and territories (Whitinui, Rodriguez de France, & McIvor, 2018). In addition, flexible delivery modes, that include online learning, can increase access, participation, and successful completion of coursework for ITCs.

With support from the federal government ministry, Indigenous Services Canada, NITEP engaged in an Indigenizing approach to redesign a set of required courses in the teacher education program to an online delivery mode. These courses were designed and taught by Indigenous and non-Indigenous teacher educators. While these courses were redesigned for a group of 15 ITCs at a NITEP regional field center in northern British Columbia, they are intended for on-going delivery with other NITEP field centers and within the on-campus teacher education program. Those involved in the revisioning of courses were committed to Indigenous education and met regularly over two years to discuss design strategies and principles across varied content areas. Instructors of the courses also met regularly as a collective to support one another in teaching their courses, sharing and appraising resources, activities, and content and generating questions concerning cultural knowledge and local context of ITCs. Though learning through online modes may not have been the primary choice for ITCs, and neither were the courses intended to be fully delivered in digital spaces, the global pandemic necessitated conditions for synchronous and asynchronous instruction.

Pedagogical Principles for Indigenizing Design

To guide the development of online instruction and learning environments for ITCs, we formulated a set of pedagogical principles for Indigenizing design. We draw on both scholarship and experience to define the following four pedagogical principles:

Indigenous knowledge frameworks

Given the rich and diverse ways Indigenous knowledges are understood, it was helpful for instructors to utilize Indigenous knowledge frameworks to assist ITCs in applying Indigenous theory or concepts to their teaching practices. Within an Indigenous knowledge framework, “there are many ways by which knowledge can be organized…including taxonomy, ceremony, art, and ritual” (Varghese & Crawford, 2021, p. 10). Indigenous worldviews are expressed within these frameworks and knowledge, concepts, or values are then classified, integrated, or structured to provide an understanding of the world around us. Indigenous knowledge frameworks in their conceptual or visual representations demonstrate the sophistication of Indigenous knowledge systems, which often face challenges of validity in their application to academic disciplines. There are a growing number of Indigenous knowledge frameworks that assist with meaningful engagement of Indigenous theories and research (e.g., see Archibald, 2008; Kirkness & Barnhard, 1991; Styres, 2017; Wemigwans, 2018) and can be applied to instructional design.

Localization

Though Indigenizing design is attentive to the diversity in languages, cultures, and practices among Indigenous groups, there are common elements that were considered in adapting the mainstream teacher education curriculum to local contexts. For example, there are common values and pedagogies among Indigenous people that include oral tradition, intergenerational approaches, land and experiential learning, and relationality and interconnectedness. Indigenous scholarship assisted instructors to be inclusive of the broader values and pedagogies for Indigenizing, drawing on Indigenous scholars, educators, authors, or artists to contribute a broad range of Indigenous perspectives in the course design. However, responding to local contexts required instructors to consult and collaborate with local community members, knowledge keepers, and students. Co-author Johanna was from the local territory and provided guidance to the instructors. In some instances, ITCs were hired to support some aspects of local course development, given their prior experience with curriculum development.

Engaging Indigenous Elders, knowledge keepers, and community members in Indigenizing course design resulted in richer and fulsome experiences for both students and instructors. Local stories, knowledge of land markers, histories of place, languages, and interactions of students with community, family, and practicing educators amplified the local aspects in the instructional design. This required instructors to consider local protocols, which are systematic rules of acquiring and utilizing Indigenous knowledges in the course. For instance, cultural protocols may include how Indigenous knowledges and oral traditions are shared in social, political, educational, and cultural ways. While many of the instructors were sensitive to Indigenous protocols, community and students assisted instructors with this element of design.

Multimodalities

In the online space, instructors were able to apply a range of multimodal forms including audio, images, texts, or videos. For instance, digital storytelling is an important mode of expression and pedagogy for Indigenous people and communities to restore, generate, document, and archive their own histories, truths, and contemporary realities (Sam, Schmeisser, & Hare, 2021). Stories in digital forms have been described as “living breath” connecting learners to their ancestors, homelands, languages, teachings, and future generations (Manuelito, 2015). Multimodality in course design enabled ITCs to share historical and contemporary cultural visual expressions, listen and create podcasts, take part in traditional knowledge activities, such as drumming, songs, rattle making, preparing traditional foods, learning about traditional plants and medicines, and listening to and observing Elders and community members who took part as online guests. Instructors drew on digital tools, learning platforms, and social media to create opportunities for ITCs to utilize the growing number of cultural and language apps and LMS platforms as modes of digital sovereignty.

Design for relationship

Relationality configures strongly within Indigenous worldviews. This includes relationships to one another, to family, community, ancestors, and to land and place. Instructors placed significance on fostering and sustaining these relationships as a pedagogical principle. Despite being geographically dispersed, online learning can still create opportunities for holistic connections among learners. Reedy (2019) found a focus on design, creation, and facilitation of online spaces that prioritizes the relational nature of learning appealed to Indigenous students. This also involved relationships with instructors, where a strong instructor presence enhanced Indigenous students’ feelings of connection, especially when the, “teacher exhibited Indigenous cultural awareness, such as taking flexible approaches to assessment time frames to enable students to balance their studies with their family and cultural obligations” (p. 141). Reedy suggests that when designing for Indigenous students, educators ensure ample opportunities for all students to make interpersonal connections and provide purposeful tools, spaces, and pedagogies to facilitate these interactions.

For instructors, an Indigenizing approach to online learning also emphasized relationships to the land. Place-based conceptualizations within digital spaces can occur through different mediums, such as messaging apps, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tik Tok, or YouTube. Morford and Ansloos (2021) analyze social media environments to examine Indigenous conceptions of land in these spaces. With a focus on Twitter, these authors surmise that “tweets become a way of digitally rematriating settler occupied lands, asserting and reclaiming them as Indigenous land imbued with Indigenous spirituality, knowledges, and relationality” (p. 297). Online learning offers possibilities for ITCs to connect with lands and territories for instructional design. These spaces are living spaces where land- and place-based relationships can be developed for students.

Indigenizing Design Exemplars

Indigenous voices in educational psychology and special education courses

The developmental literature in educational psychology often focuses on individual differences (Adams et al. 2015). Further, the field of educational psychology continues to use standardized tests and diagnostic assessment, which can be entrenched in cultural bias (Skiba, Knesting, & Bush, 2002). As such, four Educational Psychology and Special Education (EPSE) courses were re-designed with emphasis on the pedagogical principles of localizing Indigenous perspectives and digital multimodalities. The curriculum design aimed to shift the focus towards a strength-based perspective to emphasize Indigenous voices, knowledges, and traditions in regards to human development, learning assessment, and cultivating supportive school environments. The exemplar presents Indigenous voices in multimodal resources within LMS to shift from the dominant/Eurocentric individual perspective to the inclusion of Elders and knowledge keepers’ voices that express a “cultivation of collective well-being” (Adams et al. 2015, p. 221). The curriculum development gathered Indigenous voices in EPSE courses, which are shared in this exemplar.

To localize the curriculum, I (Johanna) started by consulting with faculty course coordinators, Indigenous community partners, and educational technology instructional designers. From these consultations, I established themed modules for the course. Multimodal activities within a LMS modules were asynchronous, engaging ITCs in critical reflections, peer discussions, and digital storytelling projects. ITCs were critical of the LMS in their consideration of content development when interviewing Knowledge Keepers and functions of LMS to deliver Indigenous digital resource repositories. LMS played the role of content delivery (e.g., course administration, learning resources, peer assessment) and a tool used to communicate in an online environment (e.g., announcements, messages, discussion forms). Two ITCs were hired to support local engagement with community members in the creation of digital multimodal resources. We collaborated together to interview Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and educators from the Tŝilhqot’in Nation and Nuxalk territories to create multimodal resources for the courses. The result was five short length videos that enhanced Indigenous voices in the learning design.

The ITCs and I co-developed an interview guide for the filming projects. ITCs identified individuals to interview in their respective communities. Elders and Knowledge Keepers provided their consent and permission to be interviewed. Questions posed to Elders focused on, what does it mean to live a healthy (good) life? Questions for teachers and school principals focused on, how do you create a strong community? Knowledge Keepers were asked, how does storytelling or songs shape teaching and learning?

Selected quotes from each interview are included to convey localization of Indigenous voices in the multimodal resources for the EPSE curriculum. Topics discussed in the interviews related to social and emotional development as well as cultivating supportive school and classroom environments. A Nuxalk Elder spoke about the importance of sacred knowledges.

There are medicines that have to be developed in different ways that I was taught. And also, what I was taught is that some of the medicines we only share with very, very chosen people that will carry on the ways of the medicines with strict confidence.

– E.V.Sun-Hwrna Schooner, Nuxalk Elder

In the next quote, an Indigenous school administrator who lives in the Nuxalk territory provided guidance to ITCs on how to cultivate positive relationships with students. She was asked, how do you build positive relationships with students?

Building relationships, your consistency. Your consistency of your attendance. Of them knowing you’re here for the long haul. I would say recognizing emotions. Really, really talking through and validating to make sure kids understand that you know what they are going through and it’s okay to have these big emotions. It’s definitely a long-term thing. I would say like some of the relationships I have built with kids it took years to get that close. Now, they’re comfortable walking in my door and that’s good!

– Desireé Danielson, Vice Principal Acwsalcta School

Then, a Tŝilhqot’in educator shared about the importance of building a sense of family among students, teachers, school administration, and staff for a supportive school environment. He was asked, what makes a strong learning community?

A strong community at school, first of all, you have to pretty much develop a family setting where the students come to school and feel comfortable and get along with everyone. Not to have a stress-related environment. You pretty much have to get along with everyone, staff, parents, and children. The idea is to bring back the family sense, so that when they go to school, they are comfortable in that setting. And also, you want to achieve something that they look forward to on a daily basis, so that’s what you want to develop over time. By doing this, you have to communicate with them.

– Grant Alphonse, Tŝilhqot’in Nation

Then, a Tŝilhqot’in Elder spoke about the role of grief and loss among young people. She states the importance of cultural protocols in social and emotional wellness when experiencing the stages of grief. She was asked, what stories do you know about living a good life?

I realized a lot of the young people don’t know the protocol at all. That sorta really sticks out. And being a widow, hardly nobody knows the different stages they go through. Like with some of the Elders or with somebody that’s been sick a long time and you know it’s okay, but if they die suddenly that’s when it’s more devastating. That’s what I notice, you go through a lot of stages. On top of that, when you’re a widow, you got to follow your protocol. And with grief and dealing with everything, it’s a really tough year. But a lot of what I notice is that a lot of young people come to me and ask, “how are you dealing with it?” And I tell them the different stage I am at.

– Agnes Alphonse, Tŝilhqot’in Elder

Interviews with Elders and educators conducted by ITCs assisted with the Indigenizing EPSE curriculum by engaging in local Indigenous stories, cultures, and practices. ITCs adhered to cultural protocols during the interview process. The curriculum development for the four EPSE courses enhanced Indigenous voices in a series of local community interviews to form multimodal resources that included video, audio, and text. These multimodal resources promoted relationship building among ITCs during their EPSE coursework via ongoing reflections and dialogue with peers based on the teachings presented in the interviews.

Mathematics on the land: Listening to the land and living rhythms

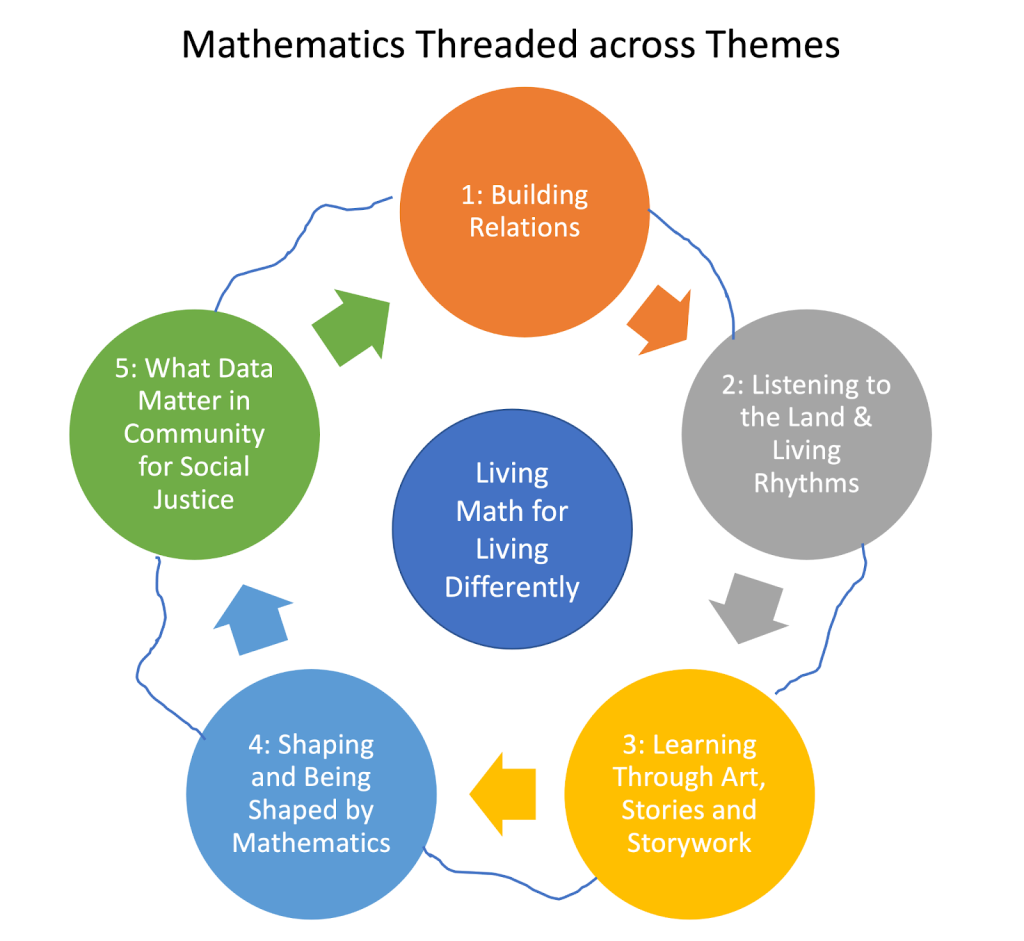

“Run Bella Run! Today is Math!” Our mathematics curriculum and pedagogy course began with one ITC voicing the sentiments of others when she posted her experience and relationship with math in this 6-word poem. Bella’s experiences, like many, describe mathematics as a subject to be feared, only done in math class, and disconnected from personal, cultural, and everyday lives. This isn’t surprising because, as Bishop (1990) argues, mathematics is a “secret weapon of cultural imperialism” considered as “one of the most powerful weapons in the imposition of Western culture” (p. 51). Indigenizing mathematics education and designing curriculum for ITCs required engaging with Indigenous design principles of relationality, Indigenous frameworks, localization, and multimodalities. Drawing upon Indigenous scholars and writers the course was rooted in five themes that focused on the importance of relationship, land, community, culture, and story (Archibald, 2008; Armstrong, 1998; Cajete, 2004; Coulthard, 2010; Ghostkeeper in Surkan, 2018; Kimmerer, 2013; Salmon, 2017; Simpson, 2017; Styres, 2017; Wagamese, 2019) with mathematics threaded across the themes (see fig. 1).

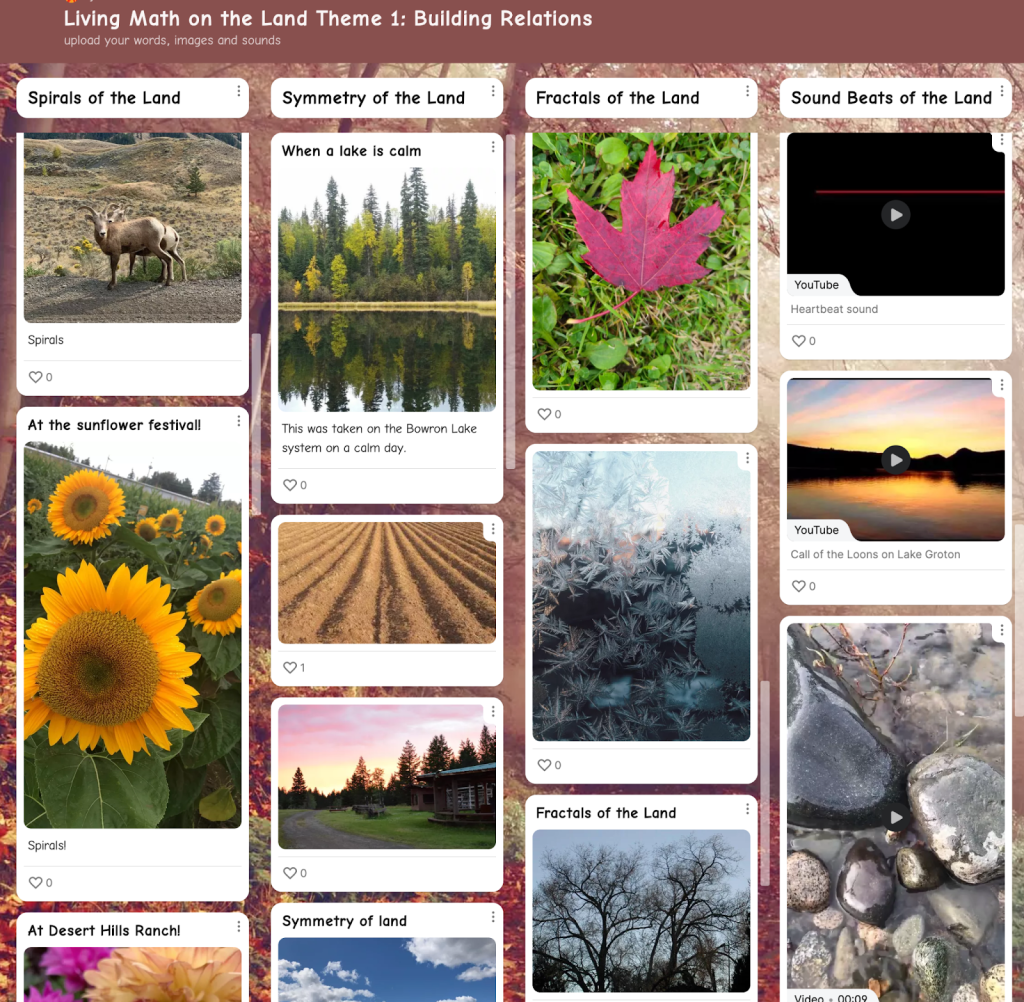

As mathematics is often an emotional and sometimes traumatic experience for many, we began the course (re)building and (re)storying relations with mathematics through shared stories of mathematical experiences and math-walks on the land. ITCs collected and posted images and sounds of mathematical patterns and rhythms they noticed around them outside, on the land, and in their homes. We pushed the boundaries of what counted as mathematical by collecting images of symmetries, fractals, spirals, and sounds in both the human-built and more-than-human worlds. We posted our findings to the course Padlet (Fig. 2) to (re)story mathematical relations and to encourage ITCs in (re)membering (Styres, 2017) that listening to the land and its patterns can bring us together even across geographic locations. Focusing on local relationships but shared and distributed digitally allowed us to explore mathematics within our own contexts and notice pattern connections: the spiral of a spider’s web in one ITC’s image was connected mathematically to the spiral in a mountain goat’s horns, the spirals in cauliflower, and to pine needle weaving of others’ images. We began building relationships with each other, our communities, and mathematics through ITCs’ shared knowledges, experiences, noticings, and stories.

For ITCs the task opened-up opportunities to acknowledge how we live mathematical actions such as noticing and studying patterns visually, orally, and with our bodies. We became each other’s teachers through sharing stories that centered Indigenous pedagogies and mathematical conversations/inquiry while at the same time decentering mathematics’ power to define who can do mathematics and who is seen successful. A series of weekly math-walks kept this relational thread alive. A math-walk noticing what comes in 2s, 3s, 4s, or 5s had one student offer how blackberry bush leaves grow in clusters of 5 sparking curiosity of others to examine berry bushes in their areas. Does this occur for all berry bushes, or just black berries, or just black berries in your area? What else grows in 5s? Another math-walk connected to ITCs’ previous contributions to developing educational resources for a digital storytelling project (Sam, Schmeisser, & Hare, 2021). This math-walk invited ITCs to explore the possible trading and economic practices along a 450 km exchange corridor known as the Nuxalk-Carrier Grease Trail, through mountain passes, forests and open meadows where westcoast ooligan fish grease was traded for blankets and tools. This math-walk offered possibilities to explore Indigenous wealth distribution, circular economies, and trading practices. A further math-walk on noticing pathways, both human and non-human, resulted in students sharing mathematical patterns of animal trails found on their mountain hikes and in gardens. Okanagan poet and scholar Jeannette Armstrong (1998) writes of the lifeforce of land that “holds all knowledge of life and death and is a constant teacher…the land constantly speaks. It is constantly communicating” (p. 176). For Armstrong land is a source of language and story. A goal of this course was to support ITCs in re-imagining mathematics as part of that story.

Stories formed a strong relational thread through the course with Ojibwe author Richard Wagamese (2019) writing that “it all begins with story” (p. 32). The course involved ITCs in exploring mathematics through story and building on the potential of story to connect mathematics and community. Stó:lō scholar Jo-ann Archibald Q’um Q’um Xiiem writes about the power of story for educating not only the mind, but also the spirit, body, and heart in her book Indigenous Storywork. ITCs were invited to inspire mathematical curiosity through experienced and embodied connections to community, specifically through story in digital, oral, and written modes. We drew upon Archibald’s (2008) Indigenous storywork principles of respect, reverence, reciprocity, and responsibility in preparing to select and design a mathematics lesson with story, to become, using Archibald’s words, “storywork-ready” (Indigenousstorywork.com). The principles of responsibility and reciprocity were particularly useful in considering stories with mathematics that could be specifically connected to, and give back to, community. Students worked in teams forming digital relationships facilitating collaborative lesson design across geographic areas.

Not all groups chose stories connected to land or culture, and no group chose oral stories. Some for example chose popular North American children’s stories such as American writer Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar where the mathematical connections were more explicit and the story perhaps more familiar and readily available during pandemic restrictions. Others chose stories by Indigenous authors including Dene writer Richard van Camp’s book What’s the Most Beautiful Thing You Know About Horses? Or Sakaw Cree writer Dale Auger’s Mwâkwa Listens to the Loon in which one ITC engaged her students in discussions of Water Beings fishing to provide food for Elders and families. One group drew upon a local cultural resource, Coyote’s Food Medicine written by Elders of Northern Secwepemc territory to design and try out lessons around mathematical patterns of seasons, gathering food, and cooking with family members within their COVID bubbles. This land-based mathematics education course brought us together in digital spaces to explore and be inspired by the study of patterns in our own land-based contexts. This provided opportunities for us to (re)story relationships with the land and mathematics, to experience the land mathematically, and to learn to live mathematics differently.

Centering land in physical and health education

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that “all peoples contribute to the diversity and richness of civilizations and cultures” (p. 2) and calls for an urgent need to reaffirm the fundamental importance of Indigenous self-determination. The call for Indigenous self-determination can be applied to Physical and Health Education (PHE), which emphasizes a lifelong approach to wellness. However, fostering Indigenous self-determination in PHE is not straightforward as there are both convergences and tensions between Indigenous and Western paradigms. For example, with its emphasis on embodied and experiential education, PHE aligns well with some of the core principles of an Indigenous paradigm (Styres, 2017; Simpson, 2014). At the same time, however, PHE has its roots in Euro-Western assumptions about movement as a decidedly individual and human-centered engagement. This individualized and anthropocentric framing is inconsistent with an Indigenous paradigm, which situates self-in-relation (Graveline, 1998) to human, more-than-human, Land, and spiritual relationships. Thus, when envisioning a course in PHE as a possible site for affirming Indigenous physical activity and health practices, the task was to attend to both the convergences and tensions at play. In doing so, Indigenous knowledges, ways of being and ITC’s experiences in PHE were centered as a pathway for cultivating different experiences for children in elementary physical and health education, which became the overarching framework for the pedagogical principles, course development, and course administration.

The learning management system enabled ITCs to gather and share their stories in (re)visioning a PHE curriculum that centered Indigenous knowledges and pedagogical principles. This was facilitated through drawing upon Mohawk scholar, Sandra Styres’ (2017) circular, four directional approach to Land-based education, the course moved through the following phases:

- (Re) Centring Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Being in Physical and Health Education

- (Re) Membering Indigenous Values of Relationships: Land, People, and Place

- (Re) Generating Knowledge Systems through Activities, Sport, and Everyday Life

- (Re) Actualizing Movement and Place-Based Knowledge Systems for Health

Both the four phases and the circular approach provided a framework that illuminated and centered the notion of self-in-relation to the knowledges, experiences, and communities, thus weaving together aspects of locality, which became the foundation of wellbeing for the course. Such an approach means that everyone in the course shared in a pedagogy that drew upon the momentum of the circle in a pendular fashion, constantly moving between phases as necessary, as opposed to a linear progression that centers pre-determined learning outcomes.

By foregrounding the experiential, kinesthetic, and affective relationships people have with local places, human movement and wellbeing, the cultural- and place-based specificity of Styres’ approach created a space online for ITCs to build a connection between traditional and contemporary practices of Indigenous wellbeing centered around their own experiences, histories, and local knowledges. In so doing, the modalities used in the digital space created a pathway to advance a sense of reciprocal relationality (Wilson, 2012) whereby the ITCs knowledge and experience shaped the course. To this end, the course specifically allowed for emergent opportunities among ITCs to identify and share the interwoven connections with Land, culture, tradition, community, physical activity, health and wellbeing.

To give a few examples, in phase one, (Re) Centring Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Being in Physical and Health Education, ITCs were invited to share an artefact that was meaningful to them that reflected their connections with physical activity, health, wellbeing, culture, tradition, or community. During the first synchronous class, ITCs shared their artefact with the larger group, and this spontaneously generated additional sharing, where participants used the chat space to offer up a number of other related resources, such as photos, videos, and maps. In so doing, the online platform became a generative and lively space where story, place, values, and experiences proliferated in unanticipated, student-centered and holistic directions. In the second phase, (Re) Membering Indigenous Values and Relationships, a pivotal moment for relational understanding emerged. ITCs were asked to share their favorite flavor of ice cream. Almost instantly gooseberry ice cream, which was referred to as “Indian ice cream,” was mentioned. The mention of Indian ice cream generated considerable excitement as ITCs voluntarily and enthusiastically shared their experiences with gooseberry ice cream. As an outsider unfamiliar with Indian ice cream, the ITCs exercised their insider knowledge, explaining to me the social, cultural, and place-based significance this particular food had for them. The class dialogue that ensued involved people sharing stories ranging from the physical activity necessary to locate, pick and preserve the berries, prepare the ice cream, all the way to sharing the desert with family and friends. It was clear that the experiential aspects of gooseberry picking were then layered with meanings about the ice cream’s texture, taste, and use. As stories were verbally shared images popped up in the chat room, photographs of berries and family were offered, links were made to YouTube, and maps of where to locate bushes were identified. Using stories and technology it quickly became apparent that every ITC in the course had a relationship with gooseberry ice cream. As a settler scholar I was both excited and fascinated by the details relayed and I remarked about how each person in the course had a relationship with this food. It was at this time, that one of the ITCs said, “of course LeAnne, it’s Indian ice cream!” I share this example to illuminate how creating online spaces where the experiences and knowledges of ITCs can be shared can lead to an environment where ITCs bring themselves into the curriculum. Although there are no guarantees with this approach, in the case study I share, this resulted in an Indigenous-centered pedagogical environment that foregrounded physical activity, health and wellbeing as experienced and determined by those in the class, not as predetermined curricular outcomes. Intentionally following Styres’ design allowed for a (re)membering of the values shared within Indigenous communities that focus on relationships, history, kinship, and community physical activity, health and wellbeing while also fostering a (re)membering that enabled pedagogical self-determination to emerge.

Conclusion

While the three Indigenizing design case exemplars are quite specific, the pedagogical principles have widespread relevance for LMS design. Indigenous knowledge frameworks guided the LMS design of the mathematics on the land as well as centering land in PHE. All the Indigenous LMS design exemplars were rooted in localization. Each course was attentive to local land, stories, languages, and traditions. Engaging members of Indigenous communities ensured that their aspirations were embedded in LMS design (Ole, 2014). Multimodalities included different interactive asynchronous activities in each Indigenizing LMS design exemplar; for instance, ITCs reported their math-walks with images and text. They also engaged in multimodal resources with video interviews and reflections on a LMS platform. The LMS design for relationships was enhanced by synchronous learning with a consistent instructor presence to foster a sense of connectedness and build relationships.

Reflections on student experiences

The Indigenizing design exemplar for Educational Psychology and Special Education (EPSE) describes part of the curriculum development for a hybrid approach. Although consultation with community partners was a starting point for this work, the inclusion of Indigenous voices in EPSE courses brought together a course instructor, educational technology designers, Indigenous teacher candidates (ITCs), and Indigenous Knowledge Keepers. The ITCs with the mentorship of the course instructor produced several interviews with Indigenous Elders and school educators. Their multimedia interviews weaved together culture and developmental perspectives. Synchronous classroom discussions and asynchronous reflections were used to engage ITCs after listening to the interviews. Yet, multimodal resources sometimes hindered the experience of some ITCs due to limited broadband internet and/or no connectivity. The multimodal resources were a catalyst for further changes in EPSE courses. It has led to discussions among faculty members about the Indigenizing design of graduate level EPSE curriculum. Through discussions with faculty, there has been an emphasis on disrupting Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) resources widely used in curriculum. That is, along with the Indigenizing of teacher education curriculum, there are discussions about how to decolonize online learning spaces. We encourage other educators to consider how to disrupt taken for granted LMS practices as a way of decolonizing education. Indigenizing design for digital mathematics education offered opportunities for ITCs to experience their communities, land, and cultural practices through a study of patterns. Building relationships and drawing upon story to explore mathematics created unexpected synergies. For example, one ITC wrote that connecting math, story, and land practices opened up possibilities to “incorporate some local Tŝilhqot’in language into the story and include local Elders to come and speak about their hunting protocols.” The study of mathematics moved toward being seen as connected rather than separated from cultural practices and the land. Our goal was for ITCs to experience mathematics for living differently, to (re)story relationships with mathematics that could, in turn, support ITCs in building caring relationships with their own students, grounded in the local, and connected to land. For some ITCs this is affirmed in learning of their own students’ experiences, where ITCs saw students noticing and creating patterns on the land and heard students claim, “their favorite part of the lessons were the land-based math lessons!”

Within the PHE Indigenous course design, the organization, structure, and pedagogical approach foregrounded opportunities for ITCs to share their cultural awareness while weaving in their vision and values for a holistic approach to physical activity and health. By creating the context for the emergence of strong relationship development both within the course and with community and by centering Land and Indigenous knowledge and ways of being, the course designed offered ITCs opportunities to build confidence in sharing their approach to wellness and its larger connection to self-determination.

Indigenizing pedagogy in online learning is an ongoing process. As these courses are being delivered in other NITEP field centers in different regions, there will be a need to be responsive to local Indigenous worldviews, histories, land and place. This iterative process reflects a commitment to Indigenizing within learning design. The revisioning of these courses may offer new ways that empower ITCs, schools, and communities.

Final thoughts

Indigenizing learning design for online learning assists ITCs in connecting with each other, their communities, and their lands and languages. We were deliberate that ITCs experience cultural knowledge and practices in new modalities they might not otherwise experience that includes digital stories, songs, language, or visual expressions. “Many cultural practices – at one time requiring an embodied presence – adapt to this contemporary reality” (de Haan, 2018, p. 14). As with Sam, Schmeisser, and Hare (2021), our design exemplars foster the pride among ITCs that is experienced when their storied traditions are narrated through audio, video, and multimodal forms. Space, voice, and agency are given to Indigenous people when their knowledges are upheld in digital forms. While the digital space is not a replacement for the experiential pedagogies that occur in physical and material worlds, we suggest alongside Morford and Ansloos (2021) that new relationships can be formed with land through online experiences. Digital environments serve to repatriate land, languages, and traditions (Wemigwans, 2018). The possibilities for honoring Indigenous knowledges and pedagogies in the digital space point us to the need for protocols guided by Indigenous ethics (Morford & Ansloos, 2021). This learning design approach through Indigenization is not only an inclusive approach. While our approach takes up equity and social justice, an Indigenizing design approach is an assertion of Indigenous digital sovereignty.

References

Adams, G., Dobles, I., Gómez, L. H., Kurtiş, T. & Molina, L. E. (2015). Decolonizing psychological science: Introduction to the special thematic section. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 3(1), 213–238. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v3i1.564

Archibald, J. Q. Q. X. (2008). Indigenous storywork: Educating the heart, mind, body, and spirit. UBS Press.

Armstrong, J. C. (1998). Land speaking. In S. Ortiz (Ed.), Speaking for the generations: Native writers on writing (pp. 174–195). University of Arizona Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv27jsm69.11

Auger, D. (2006). Mwâkwa talks to the loon: A cree story for children. Heritage House Pub.

Bishop, A. J. (1990). Western mathematics: the secret weapon of cultural imperialism. Race & Class, 32(2), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/030639689003200204

Brayboy, B. M. J. & Maughan, E. (2009). Indigenous knowledges and the story of the bean. Harvard Educational Review, 79(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.1.l0u6435086352229

Cajete, G. (2004). Philosophy of native science. In A. Waters (Ed.), American Indian Thought (pp. 45–57). Blackwell Publishing.

Cajete, G. (2015). Indigenous community: Rekindling the teachings of the seventh fire. Living Justice Press.

Camp, R. V. (1998). What’s the most beautiful thing you know about horses? Children’s Book Press.

Carle, E. (1994). The very hungry caterpillar. Philomel Books.

Castagno, A. E. (2012). “They prepared me to be a teacher, but not a culturally responsive Navajo teacher for Navajo kids”: A tribal critical race theory analysis of an Indigenous teacher preparation program. Journal of American Indian Education, 51(1), 3–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43608618

Cote-Meek, S. (2014). Colonized classrooms: Racism, trauma and resistance in post-secondary education. Fernwood Publishing.

Coulthard, G. (2010). Place against empire: Understanding Indigenous anti-colonialism. Affinities: A Journal of Radical Theory, Culture, and Action, 4(2), 79–83.

Gaertner, D. (2015). Indigenous in cyberspace: CyberPowWow, God’s Lake Narrows, and the contours of online Indigenous territory. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 39(4), 55–78. https://doi.org/10.17953/aicrj.39.4.gaertner

Garcia, J. & Shirley, V. (2013). Performing decolonization: Lessons learned from Indigenous youth, teachers and leaders’ engagement with critical Indigenous pedagogy. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 28(2).

Grafton, E. & Melançon, J. (2020). The dynamics of decolonization and indigenization in an era of academic “reconciliation.” In Sheila Cote-Meek & T. Moeke-Pickering (Eds.), Decolonizing and indigenising education in Canada (pp. 135–154). Canadian Scholars.

Graveline, F. J. (1998). Circle works: Transforming eurocentric consciousness. Fernwood Publishing.

Haan, K. de. (2018). Indigenous territory in cyberspace: Exploring the cultural and metaphysical consequences of territory beyond materiality. The Ethnograph, 13, 14.

Hare, J. (2021). Trickster comes to teacher education. In G. Li, J. Anderson, J. Hare & M. McTavish (Eds.), Superdiversity and Teacher Education (pp. 36–51). Routledge.

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Milkweed Editions.

Kirkness, Verna. J. & Barnhardt, R. (1991). First Nations and higher education: The four r’s- respect, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility. Journal of American Indian Education, 30(3), 1–15.

Manuelito, B. K. . (2015). Creating space for an Indigenous approach to digital storytelling: “Living breath” of survivance within an Anishinaabe community in northern Michigan [Doctor dissertation, Antioch University]. https://aura.antioch.edu/etds/212

Morford, A. C. & Ansloos, J. (2021). Indigenous sovereignty in digital territory: a qualitative study on land-based relations with #NativeTwitter. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 17(2), 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/11771801211019097

Ole, K. B. R. (2014). E-learning principles and practices in the context of Indigenous peoples: A comparative study.

Pete, S., Schneider, B. & O’Reilly, K. (n.d.). Decolonizing our practice: Indigenizing our teaching. First Nations Perspectives, 5(1), 99–115.

Reedy, A. K. (2019). Rethinking online learning design to enhance the experiences of Indigenous higher education students. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(6), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5561

Salmón, E. (2017). No word. In G. van Horn & J. Hausdoerffer (Eds.), Wildness: Relations of people and place (pp. 24–32). University of Chicago Press.

Sam, J., Schmeisser, C. & Hare, J. (2021). Grease trail storytelling project: Creating Indigenous digital pathways. KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.18357/kula.149

Simpson, L. (2014). Land as pedagogy. Nishaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization, Indigeneity, Education and Society, 3(3), 1–25.

Simpson, L. (2017). As we have always done: Indigenous freedom through radical resistance. University of Minnesota Press.

Skiba, R. J., Knesting, K. & Bush, L. D. (2002). Culturally competent assessment: More than nonbiased eests. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 11(1), 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1014767511894

Styres, S. (2017). Pathways for remembering and recognizing Indigenous thought in education: Philosophies of Iethi’nihsténha Ohwentsia’kékha (Land). University of Toronto Press.

Surkan, J. (2018). Conversations: Elmer Ghostkeeper. The Métis Architect. https://metisarchitect.com/2018/06/04/conversations-elmer-ghostkeeper/

Thijs, A. & Akker, J. V. D. (2009). Curriculum in development. Netherlands Institute for Curriculum Development.

Varghese, J. & Crawford, S. S. (2021). A cultural framework for Indigenous, local, and science knowledge systems in ecology and natural resource management. Ecological Monographs, 91(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1431

Wagamese, R. (2019). One drum: Stories and ceremonies for a planet. Douglas and McIntyre.

Wemigwans, J. (2018). A digital bundle: Protecting and promoting Indigenous knowledge online. University of Regina Press.

Whitinui, P., France, C. R. de & McIvor, O. (Eds.). (2018). Promising practices in Indigenous teacher education. Springer Singapore.

William, J., DeRose, C. & Camille, C. (2018). Coyote’s food medicines. Doctors of BC. https://www.fnha.ca/WellnessSite/WellnessDocuments/Coyotes-Food-Medicines.pdf

Wilson, S. (2012). Research is Ceremony. Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Publishing.