4 Compassionate Learning Design as a Critical Approach to Instructional Design

Daniela Gachago; Maha Bali; and Nicola Pallitt

COVID-19 has forced a global emergency pivot to online learning, which has led to increased demand on both educators and learners, with a major impact on workloads, research careers, and mental health. Across the globe, academics complain of burnout, exhaustion, and lack of self-care. This has heightened the concern around the well-being of learners and staff (Czerniewicz et al, 2020; Imad, 2021) and has led to an increase in interest in approaches to teaching and learning that recognise the importance of care and compassion, such as humanising pedagogies (Pacansky-Brock, 2020); pedagogies of care (Bali, 2020) or trauma-informed approaches to pedagogy (Imad, 2021; SAMHSA, 2014; Costa, 2020).

Educators drawing on these approaches are concerned with their learners and their socio-emotional wellbeing. They see learning as happening when we learn in communities and when we feel we belong. Here the learning environment and the way we facilitate learning and community become as important as the course content. As Borkoski (2019) argues, “There is consensus in the literature about the benefits of a student’s sense of belonging. Researchers suggest that higher levels of belonging lead to increases in GPA, academic achievement, and motivation”

Designers often hear about “empathy”, “care”, “compassion”, “inclusive design”, and “trauma-informed” as part of their professional work. However, there is also a lack of consensus around the meanings thereof, or how accounting for them influences their learning design processes and outcomes. This contribution offers a critical engagement with these concepts, examining the relationships between these and their use in design models and approaches. We provide an alternative model that positions empathy and compassion along a continuum with design considerations that recognise and work with the power relationships between educators and learners to create opportunities for learner agency, participation, and empowerment. Our model draws from affect theory and is informed by perspectives on empathy, care, and compassion but is also underpinned by a social justice agenda. It involves choices and considerations that instructional designers or learning designers and educators make in their relationships with learners following a continuum of design approaches that exemplify the level of learner participation by designing to, for, with, by, and as learners (adapted from Wehipeihana, 2013).

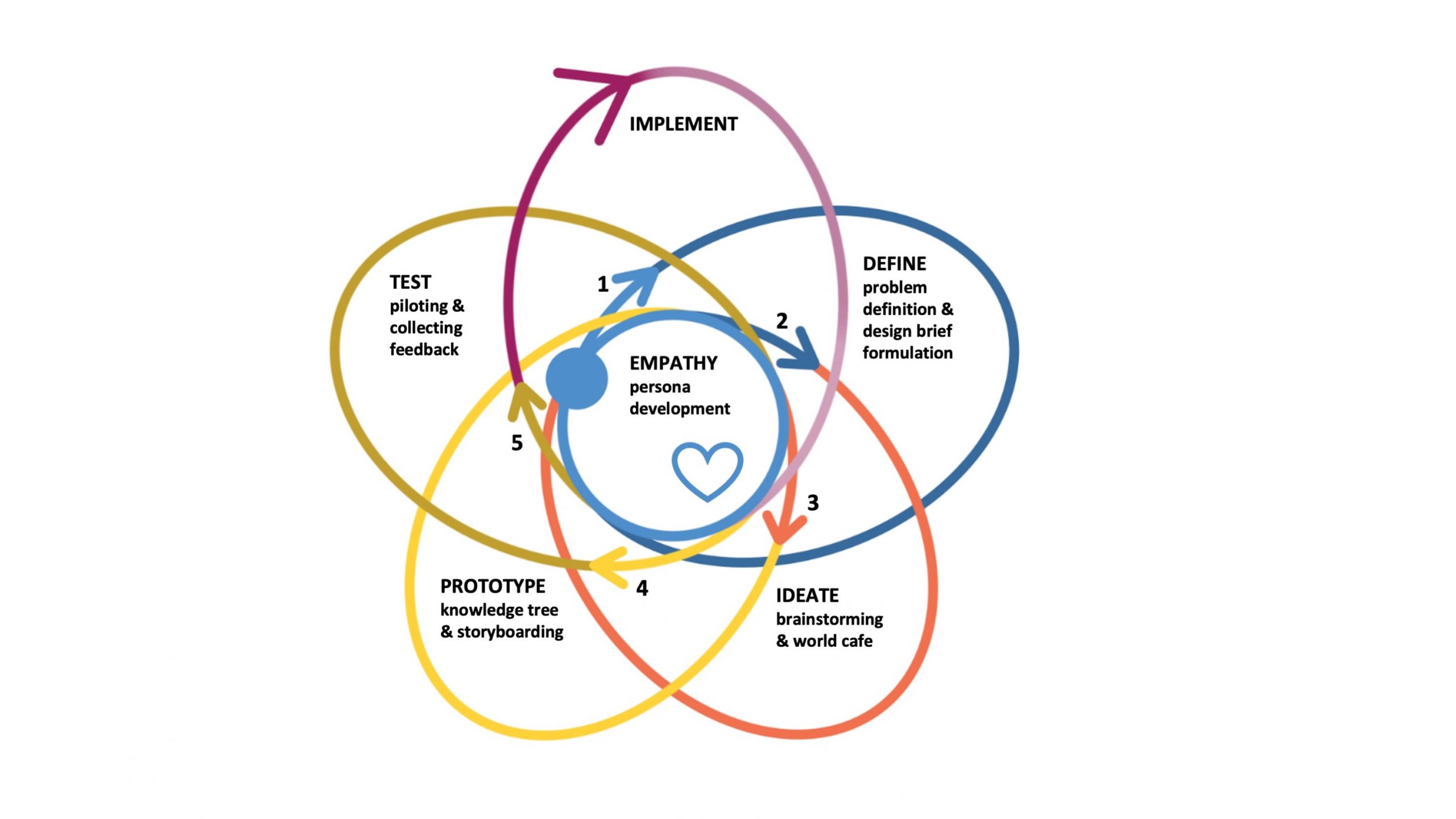

In previous work (see for example Gachago et al, 2021), we have expanded the traditional instructional/learning design approach by integrating principles and activities from the design thinking literature to develop a learning design model that would put empathy at the centre of all design decisions.

Design thinking traditionally starts with developing a “persona”, which is a user archetype, visually represented, that helps to focus a design activity on a particular individual or user, in a specific context (Anvari & Richards, 2018; Van Zyl & De la Harpe, 2014). In this activity, participants are asked to imagine one typical learner in their class (this can be a real learner or a fictitious learner made up of many of the learners they have encountered in their teaching practice) and to describe this learner in detail (including demographic details, educational history, professional career, motivation, strengths, challenges and the like). It is important to give this person a name and to make them as authentic as possible. We use flip chart paper and whiteboard markers and participants present this persona to the rest of the group. Sometimes lecturers express their discomfort about “stereotyping” or “labelling” learners. We take care to address these concerns in a sensitive and empathetic manner (see Van Zyl & De la Harpe, 2014). The persona flip charts are pinned to the wall, serving as a constant reminder of the people we are designing with and for throughout the different stages of the learning design process. These personas can represent current learners and their challenges but also future learners, or graduate personas representing learners who have completed their course/qualification. This is a useful activity to unpack how graduate attributes can be integrated across curricula. However, we have also felt increasingly frustrated by two factors that seem to be implicit in learning design models drawing from design thinking.

- The assumptions about who learners are (as exemplified by the traditional persona activity, that many of our design processes start with), and designing a priori based on that, rather than in response to who the actual learners turn out to be, and how to create designs responsive to those different learners (and learners that might change with each iteration of a course)

- The use of empathy interviews and personas also does not question positionality or biases of the designers themselves when they conduct and interpret interviews and create and design for personas. Again, the choice of whom to interview, how to interpret this data, and how this impacts the development of personas is not impartial and is not the same as designing “with” the actual learners.

In this contribution, we are exploring what it would mean to replace empathy with compassion, which we see as more concerned with equity and justice, following educators writing about affect in the classroom such as Megan Boler (1999), and Michalinos Zembylas (2008; 2011). These authors argue that feeling empathy for the other is not enough, as it creates both distance (Boler, 1999) and a superficial understanding of difference (Zembylas, 2008). Rather, these authors call for a more critical engagement across difference, one that recognises the need to engage with difference both on a personal but also systemic level, emphasising a collective responsibility for the other, that motivates action. Elizabeth Segal (2007) defines this as going beyond the feeling-for or feeling-with an individual towards understanding the social and political structures of our society. This then is much more than “putting oneself in the other’s shoes,” but assumes responsibility for one’s own role in somebody else’s story. It creates urgency for practice, for action. This move from empathy to compassion is not an easy process and not always possible within contexts constrained by institutional requirements and limited resources.

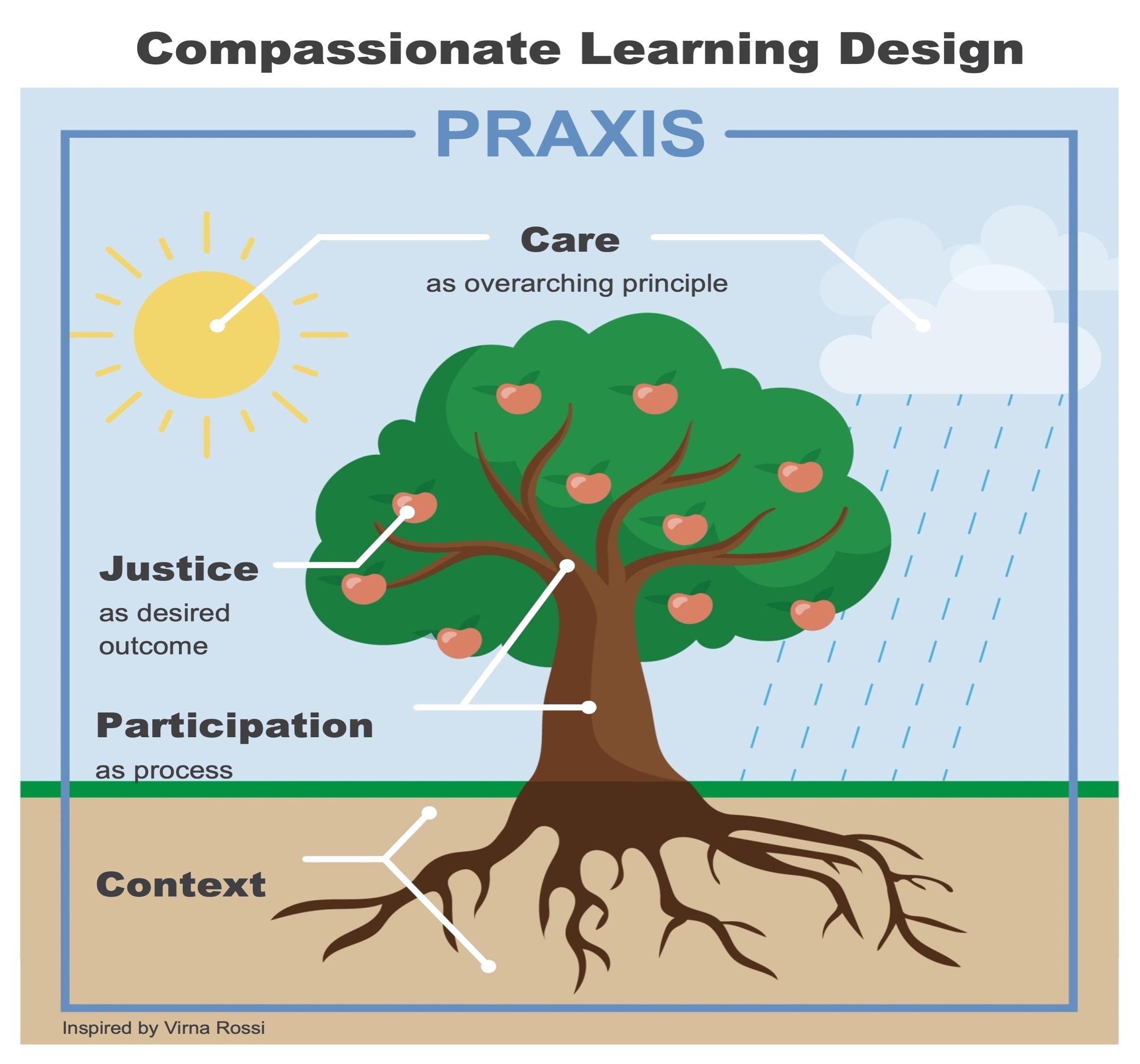

We define compassion within the context of learning design along four dimensions: a desire to create more participative spaces, a recognition of power and positionality and how this affects our ability to participate, and finally a centreing of affect in the learning process. These three dimensions should then lead to a fourth dimension: the commitment to act towards more socially just learning design approaches, what we term praxis leaning on Paulo Freire’s work, who argues that we need both “reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it” (1970, p. 51).

In this chapter, we will first introduce the four dimensions that constitute our compassionate learning design model. The model is based on a desire for more participation, an understanding of positionality and power dynamics in the classroom, the importance of affect, and how care and our mutual responsibility for each other lead to action. We then provide examples of how these principles could work together in practice. We use the terms “educator” and “learners” in a sector agnostic way, inclusive of school and post-school teaching and learning settings. Drawing on notions of teaching as a design science (Laurillard, 2012) we also use the term “designers” to refer to educators and Instructional or Learning Designers.

Towards Compassionate Learning Design: The Praxis of Participation, Justice, and Care

How does this work on empathy and compassion in the classroom relate to our work in learning design? In particular in traumatic times as we have experienced over the last two years? We are deeply concerned with designing for social justice, and we see compassion as coming from a place of care, a sense of justice, a desire to empower through increased participation levels of learners, and a compulsion to act collectively to recognise and act upon the emotional and mental health challenges and social need within our community in a reciprocal manner. However, we are also acutely aware that we live in highly unequal contexts and that power dynamics rule our classrooms, our relationships with other educators and with learners, and the relationships of learners among each other. As Sarah Sentiles (2017) states, quoting Judith Butler: “We are bound by what differentiates us as unique and irreplaceable and by our responsibility to others we don’t understand. As Butler writes, ‘Your story is never my story.’ What’s required is staying in relationship, even when we can find no common ground. Especially when we can find no common ground” (para. 7). This is why Zembylas’ or Boler’s writings on compassion when listening to stories of trauma, while they write from different contexts (teacher education in Cyprus and Canada), are so useful for us to think through what compassionate learning design would look like.

Recognising that we are different from our learners, and they may be different from each other is an important starting point, as Sarah Sentiles (2017) reminds us: “The challenge is to learn to live with, and protect, what we can’t understand” (para. 6) It therefore seems essential not to assume that educators can fully know what learners want or need: “In the caring approach, we would prefer to advise: do unto others as they would have done unto them” (Noddings, 2012). Applied to education, we could say, “Do unto students as THEY would have done unto THEM” (Bali, 2021). But what does it mean to do to learners as they would want done unto them? How do we know what learners want done unto them, recognising our own positionality as educators in interpreting what learners need and how their needs might be addressed, and recognising the power dynamics among learners themselves?

We are influenced by several scholars who write on this. Firstly, Nancy Fraser (2005) developed the term “parity of participation”, ensuring that everyone has equal power of decision-making when they come to the table. It means that “all the relevant social actors […] participate as peers in social life” with an emphasis on the process involved “in fair and open processes of deliberation” (Fraser, 2005, p. 87). However, Fraser recognises that social injustice can occur across three dimensions: economic (access to resources), cultural (recognition), and political (representation). All three of these must be addressed in order for parity of participation to occur. Participation of “those who are intersectionally disadvantaged” is essential, along with recognition of their culture, “to ensure a more equitable distribution of design’s benefits and burdens; fair and meaningful participation in design decisions; and recognition of community-based design traditions, knowledge, and practices” (Costanza-Chock, 2018). However:

Our choices are deeply shaped by the structure of opportunities available to us so that a disadvantaged group comes to accept its status within the hierarchy as correct even when it involves a denial of opportunities… In turn, our agency and well-being are diminished rather than enhanced… Unequal social and political circumstances (both in matters of redistribution and recognition) lead to unequal chances and unequal capacities to choose. (Walker & Unterhalter, 2007, p. 6)

Therefore, simply creating a participatory space and inviting marginalised groups is unlikely to magically create equity, due to historical internalised and institutional oppressions. In order to achieve socially just participation, we must recognise that “justice needs care because justice requires the empathy of care in order to generate its principles” (White & Tronto, 2004, p. 427, citing Okin, 1990). We must also recognise variability in individuals’ capacities: “the notion that one model of care will work for everyone is absurd…humans vary in their abilities to give and receive care” (White & Tronto, 2004, p. 450). If we strive towards democratic care, we need to place ourselves in the positions of both caregivers and receivers:

[D]emocratic care requires switching perspectives and not just thinking about what we want. We need also to look at care from the standpoint of care-receivers, who will have different ideas about what kind of care they want or need to receive… In a “caring-with” democracy, we can set a goal of structuring institutions and practices so that each person’s individual preferences can be honored. (Tronto, 2015, p. 34)

Therefore our understanding of compassionate learning design has four dimensions:

- The desire to increase agency and participation of learners in their own learning process – PARTICIPATION

- An understanding of power and history and how that affects our ability to participate: our positionality and intersectionality and how they influence our critical pedagogy – JUSTICE

- A recognition of importance of affect and how that impacts learning: humanising, caring, and trauma-informed pedagogies – CARE

- The aforementioned dimensions resulting in a commitment to act, to take responsibility and move towards more socially just learning design – PRAXIS

Figure 2 shows the relationship between care as overarching principle, participation (parity) as process, and justice as a desired (even if never reached) goal—with praxis as the result of these intersecting elements.

Compassionate Learning Design as Participation, Justice, Care, and Praxis

Participation

“[R]adical pedagogy must insist that everyone’s presence is acknowledged…There must be an ongoing recognition that everyone influences the classroom dynamic, that everyone contributes” (bell hooks, 2014).

Humanising pedagogies draw from Paolo Freire (1970) and other critical pedagogues who describes humanising pedagogy as a revolutionary approach to teaching and learning that “ceases to be an instrument by which teachers can manipulate learner, but rather expresses the consciousness of the students themselves” (p. 51). Challenging the “banking system” of education, Freire advocates for learning that is based on problem-posing learning, dialogue, embodied learning, and democratic access to information to allow for transformative education. All of this needs the inclusion of learners in decision-making processes to create the space for dialogue and democrative education.

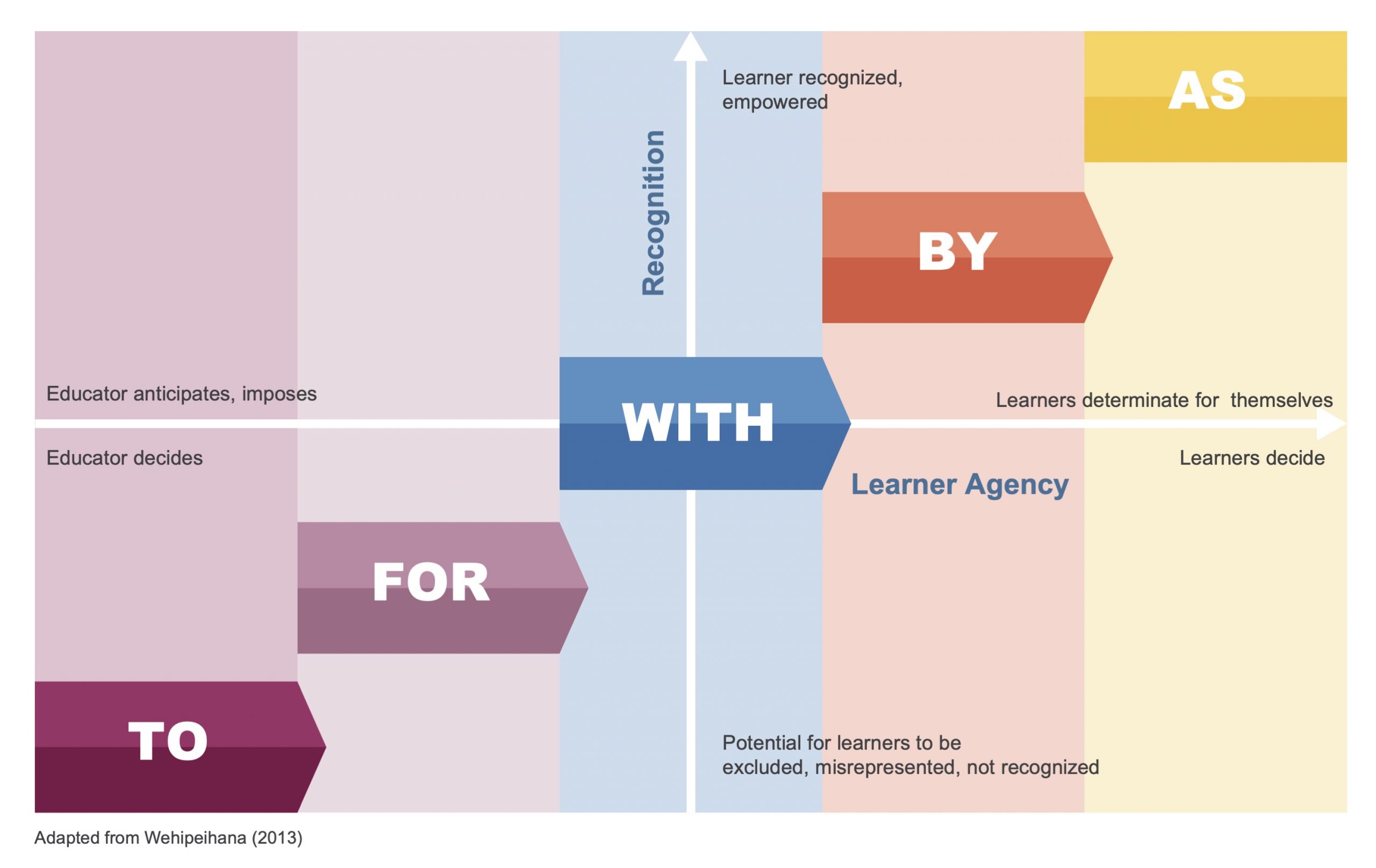

Wehipeihana’s (2013) model of Indigenous evaluation can be helpful in showing different approaches to participation. Her model is about Western evaluation with Indigenous groups, and the levels of doing so involve:

- TO: evaluation done TO indigenous group, Western experts know best, and this is the most harmful form of evaluation

- FOR: evaluation done FOR Indigenous groups but by Westerners, which is benevolent but patronizing

- WITH: done together but probably with Western ways of doing things. This is the first step towards participation

- BY: done by and led by Indigenous groups (representation) but possibly still using world views of the West or need to explain ways of doing things—i.e. bringing participants to a table where the table is already set

- AS: led by Indigenous people and also complete autonomy to do so with their worldview and not having to justify—i.e. participants design their own table

Inspired by this model, we adapt it to compassionate learning design: we replace the Westerner/Indigenous groups with Educator/Learners and start from a place of benevolence where the educator wishes to act empathetically, and moves towards learner participation where compassion lives. These different levels refer to their process of deciding how to do so. We work with considering the needs and interests of actual learners rather than fictitious personas, since personas can become “objectified assumptions [which] then guide product development to fit stereotyped but unvalidated user needs” (Costanza-Chock, 2018). We ask how our design decisions impact on who/what is included and excluded? We move along two axes of increasing learner agency (political representation and parity of participation as in Fraser’s work) in order to enhance learner empowerment and recognition (the cultural dimension of Fraser’s work). Our adapted model would be represented by Figure 3 and described as follows:

- TO: educator knows and anticipates what learners need and offers one solution they believe will alleviate suffering or enable learners to learn best. This comes from a place of care but does not involve learner participation; it assumes educator’s knowledge and expertise. More than anything, the educator prioritises the needs: they decide if the need for inclusion is paramount, or the need for economic security, or the need for something else, and because the educator has their own identity and positionality, they may not be fully aware of the spectrum of needs of learners, and which ones are a priority to tackle; they may make decisions about solutions that do not suit every learner.

- FOR: educator knows and anticipates what learners need, perhaps after asking them what they need via survey or asking in class, perhaps offering two solutions to choose from, thought of by the teacher independently without consulting with learners; it assumes educator has expertise. It is slightly better than the above because it involves some level of learner input, but again, the input from learners has to fit the boxes the educator has prioritised as important, and has decided can be open to some level of learner input, to the degree that the educator allows: learners make choices among options offered by the educator.

- WITH: educator and learners discuss needs and come up with a range of solutions together, but facilitated by the educator, probably within some institutionally-imposed restrictions. It involves nurturing learner agency, while maintaining overall power of setting parameters of negotiation in the hands of the educator. This can open the space for learners to bring in diverse needs and priorities not previously known to the educator, and to suggest strategies for addressing them not necessarily within the educator’s existing arsenal of possible solutions.

- BY: learners organise themselves (with light facilitation perhaps) to discuss their needs, suggest a range of solutions, usually coming up with solutions similar to ones used by facilitators in the past, and need approval of the educator in the end in order for their solutions to be “accepted” within the institution for a degree or a grade or accreditation.

- AS: learners organise themselves without constraints of facilitator or institution, and do not need to justify their worldview, approach or choices in the end. This is learner self-determination. This could occur within an educational institution in some extra-curricular experiences or in community engagement projects, or outside of formal education altogether.

The following dimensions are present throughout the process, and reflective praxis around these considerations helps to enable moving from educator-led to learner-generated and from empathetic to more compassionate learning designs. There may be institutional constraints on an educator’s ability to move towards more participatory levels in their practice, but it is important to enact as much empathy/compassion as possible within those constraints and to recognise the limitations within each level, while striving towards finding opportunities to enrich participation in areas where there is freedom to do so. Educators can also try to resist and advocate on an institutional level and form allyships for changing institutional policies and practices that go against caring, empathetic approaches, such as rigid grading policies.

Justice

Even as we move across these levels of self-determination of learners, we need to consider the unequal distribution of power between educators and learners and amongst learners themselves. We also need to question, to what extent, within formal educational contexts governed by institutional policies and external accreditation requirements, educators and learners can subvert and resist directives that reproduce injustice and reduce learner autonomy, as well as how historical constraints and oppressions have been internalised by some, and may influence their capacity to envision or express radical options. Moreover, as academic developers (or learning designers) supporting educators, we need to think of how encouraging and advocating for a compassionate design influences our process of working with educators who have different positionalities and teaching philosophies?

Is the role of the critical instructional/learning designer to advocate for particular pedagogical approaches based on their own values? Is their role to support educators implementing their own teaching philosophies? What if the educator’s teaching philosophy and approach goes against the values of compassionate design, if care and social justice are not at the forefront of their minds? What if they have internalised beliefs that compassion goes against rigour, or what if institutions discourage compassionate approaches? As bell hooks reminds us, “Teachers who care, who serve their students, are usually at odds with the environments wherein we teach” (bell hooks, 2003, p. 91).

In practice, this may mean that, for example, we find the following scenarios:

An educator in a university may not have control over learning outcomes as they are predetermined by their department, but they can for example work “with” learners to decide on a range of assessments that can be used to meet those outcomes, and the rubrics may be created “by” learners working together. Underlying this praxis should be values of compassion and social justice, such that learners working together strive towards equitable processes and outcomes for each other and not just for their own parochial interests or ones they naturally empathise with based on their intersectional identities and past experiences.

In another situation, an educator teaching a graduate course may have freedom to co-create learning outcomes “with” learners, possibly having different groups of learners having different outcomes, and have learners work independently to develop their own individual assessments and assessment criteria (“as”), with feedback from the class community, but without requiring educator approval.

In both of these models, the educators’ own positionality and intersectional identities and experiences of learners need to be considered, as any collaborative negotiation among learners is not inherently equitable, and learners unused to making choices and decisions are not necessarily well-prepared to participate in empowering ways (EquityXDesign, 2016). Sarah Sentiles writes: “The challenge is to learn to live with, and protect, what we can’t understand… For the theorist Judith Butler, the ethical surfaces not when we think we know the most about each other, but when we have the courage to recognize the limits of what we know. Like Levinas, she proposes an ethical system based on difference, on relationships with others unlike you” (2017).

Activities that could be included in learning design processes that would allow educators and learners to reflect on their positionality are, for example, co-creating empathy maps and persona activities, not only for learners but also educators. If one maps the actual, not imagined, learner personas and educator personas, one might be able to see where overlaps are but also where gaps in understanding could occur. Other examples are Meta-Empathy Maps, which consider not only individual circumstances, but also institutional and structural conditions, that either include or exclude learners (EquityXDesign, 2016). Enriching these design activities with storytelling spaces allows for lived experience to surface and for a deepening of relationships between educators and learners and learners among themselves. Also raising awareness of the challenges of working across differences in co-design spaces is important and there are useful guidelines for working with and across hierarchies. In general, creating spaces for pause, for meta reflection, for preparing and supporting collaboration alongside the collaboration itself is recommended if one desires to create spaces that are truly participatory (see for example Ngoasheng et al, 2019 or Bradshaw, 2017).

Care

“To teach in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of our students is essential if we are to provide the necessary conditions where learning can most deeply and intimately begin” (bell hooks, 2014).

Over the last year, approaches to teaching and learning that centre care and concerns for learners’ well being have gained traction. Michelle Pacansky-Brock (2020) for example developed four principles for a humanising online pedagogy, that prioritises and serves connection and a feeling of belonging, “the connective tissue between students, engagement, and rigor” (ibid, p. 2):

- Trust: As educators, it is our responsibility to intentionally cultivate learner trust, and one way to do it is by practising “selective vulnerability” (Hammond, 2014 cited in Pacansky-Brock, 2020) in the online communities we build with our learners. As examples she mentions choosing to share aspects of our life that portray us as a real person—telling stories about a personal struggle we worked through or recording a video while cooking dinner or walking our dog.

- Presence involves intentional efforts to construct our authentic self through brief, imperfect videos to ensure our learners know we are in this journey with them (Costa, 2020). Verbal and nonverbal cues add context to our communications, which is particularly important to support culturally diverse learners.

- Awareness is achieved by learning about who our learners are and how we can support them.

- Empathy requires us to slow down, see things through our learners’ eyes without judgement, be flexible, and support them towards their goals.

In similar fashion, Maha Bali (2020) advocates for a pedagogy of care, which allows us to get to know our learners and our learners to get to know us. This means making ourselves vulnerable, modelling sharing, so our learners become comfortable to share with us. As bell hooks suggests “empowerment cannot happen if we refuse to be vulnerable while encouraging learners to take risks.” Bali calls this a hospitable environment, where everyone is given the space to choose whether and how to share. She also emphasises the importance of empathy with learners, while understanding and recognising that one can never fully understand what the other is going through. In Bali’s model, educators enact relational care (Noddings, 2012) at various levels: At the course design/planning level, in habitual practices in the classroom, in the ways they respond to learners in the class environment, and finally, in their one-on-one interactions with learners. Crucial to this notion is combining both equity and care (Bali & Zamora, 2020; Bali & Zamora, 2022a), manifesting in “democratic care” (Tronto, 2015), “parity of participation” (Fraser, 2005) and/or “Intentionally Equitable Hospitality (Bali et al, 2019; Bali & Zamora, 2022b). Some elements of this need to occur at an institutional level, or else the burden of affective care will fall on a few individuals, and the care will be selective and only ameliorative, rather than systemic or transformative. Short-term examples of institutional care can be seen in the establishment of “meeting free weeks” or institutional leave days for all employees (including academics and support staff). An example with more longer-term impacts of this in practice is how the University of Michigan Dearborn helped resist the use of remote proctoring technologies that reproduce inequalities and increase learner anxiety (see Silverman et al, 2021). They recognized that asking all educators to change their exams into alternative assessments would be a heavy burden of labor hours, and so they hired human graders to help grade these more complex assessments, instead of asking educators to accept the additional workload. Another example (see Bali & Zamora, 2022a) would be institutional support for learners with disabilities, where an allyship between a center for disability services, IT accessibility support, and teaching faculty exists so that individual educators did not have to scramble to find solutions for teaching learners with hearing or visual disabilities on a case by case basis.

Trauma-informed approaches to pedagogy have been used in higher education by educators with neuroscience and trauma and resilience training such as Mays Imad (2021, 2020) and Karen Costa (2020). Both draw on the Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) definition of trauma and its six principles that guide a trauma-informed approach: safety, trustworthiness and transparency, peer support, collaboration and mutuality, empowerment and choice; and cultural, historical and gender issues. SAMHSA (2014) defines trauma as “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.”

Mays Imad (2020) brings the notion of trauma into a Higher Education space and argues that trauma-informed pedagogy involves awareness of learners’ past and present experiences, and how this impacts their well-being and ability to learn. Imad suggests that learning cannot happen when learners are dealing with trauma. She shows, from neuroscience research, how emotions influence learning. Therefore there needs to be space within the learning experience to engage and reflect on emotions. It is only “when our nervous system is calm, [that] we are able to engage socially, be productive, and process new information in order to continue to learn and grow—and to feel we are living meaningful and fulfilled lives” (p.2). She argues that in times of COVID-19, making space for engaging with trauma was particularly important, as both learners and staff experienced trauma, primary or secondary, which happens when learners and teachers witness each others’ trauma and transfer trauma to others. Experiences of trauma include sickness and loss of family and friends, loss of employment, or “just” the experience of month-long isolation and loss of contact.

From our experience, before the pandemic, educators in general saw concerns around mental health and learner well-being not necessarily as integral to their own classroom practice, but rather as something to be “outsourced” to the university counselling centre and something they had little control over—they neither felt that their classrooms were spaces that could contribute to learners’ anxiety or depression, nor as spaces that could help promote wellbeing of learners without necessarily becoming counselling or therapy sessions.

With the pandemic we started seeing more educators recognise trauma (our own and that of our learners) as part of their classroom practice and the recognition that how they design learning matters in terms of how to respond to this trauma, to ensure that learners feel safe, empowered and connected. We recognize that some disciplines lend themselves to more space for engaging emotions. However, checking in with learners about how they feel each day, being attuned to how we assign them work and how it makes them feel, and discussing how they feel when working on a difficult project are all practices that can happen in any course or any discipline. Educators can redesign their courses in ways that better enable learners to heal and succeed with the support of their community despite the trauma they experience.

Trauma-informed approaches aim at reducing uncertainty to foster a sense of safety, level communication to help forge trust, reaffirm or re-establish goals to create meaning, make intentional connections to cultivate community, and centre well-being and care. The word “trauma” has been used in a more collective sense as well in the pandemic context as a shared traumatic experience, given diverse positionalities we know that individuals have been affected differently.

Commitment to praxis (reflection and action)

Once these three dimensions (participation, justice, and care) are in place, we believe that the fourth dimension comes to play, i.e. where educators can commit to action, in our case to a more socially just learning design. Table 1 integrates Weihipehana’s participation model with our elements of compassion learning design, to allow us to think through the various stages of participation, justice, and care. We are thinking through important questions or design considerations, such as who is the individual (or group) making key decisions, who has final approval power, what kind of conditions are conducive to this level, and examples for that level of participation and how justice and care would appear in each of them. This is thinking-in-process and we would appreciate feedback and further development by readers.

| PARTICIPATION | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TO | FOR | WITH | BY | AS | |

| Who takes decisions? | Educator takes design decisions based on anticipation / experiences from previous learners / courses (ie through a persona activity) | Educator takes decisions based on what is known from preliminary knowledge from actual learners (ie through surveys / focus groups)) | Educator and learner take decisions together, facilitated by educator who sets constraints what possible (ie in a co-design process) | Learners take decisions with participation by lecturer, but are in charge, lecturer sets some constraints (student as partners) | Learners take decisions, process led by learners, educators not necessarily involved/do not approve (student-led designs) |

| Approval | Educator | Educator and Learners |

Educator and Learners |

Learners and Educator |

Learners |

| Conditions | Educator constrained by institutional requirements, such as set curricula, accreditation requirements, unified assessments etc. | Educator constrained by institutional requirements, such as set curricula, accreditation requirements, unified assessments etc but educator has some agency in terms of setting teaching and learning activities, assessments etc. | Certain amount of flexibility and agency for educator to set parameters, such as learning objectives, curricula, T&L activities, assessments | High level of flexibility and agency for educator to set parameters, such as learning objectives, curricula, T&L activities, assessments | Complete freedom, learning happens outside institutional constraints |

| JUSTICE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TO | FOR | WITH | BY | AS |

| Little reflection on power and hierarchies | Some reflection as educator responds to learners’ feedback. | Reflection on power and hierarchies and how this affects collaboration between educator and learners is critical. Need for a parallel process to reflect on how power affects on participation. | Reflection on power and hierarchies and how this affects collaboration between educator and learners is critical. Need for a parallel process to reflect on how power affects on participation | Focus on reflection on how power dynamics affect relationships between learners themselves. Educator’s role is to lay the foundations for this but not be involved in the actual decisions |

| CARE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TO | FOR | WITH | BY | AS |

| Educator decides what learners may need and anticipates ways to care | Educator surveys learners, and this informs options the educator offers learners | Educator and learners openly discuss care needs and rights, and options | Learners drive the process to establish and implement strategies for care, educators approves, experiences of trauma integrated into curriculum | Learners establish strategies for caring for each other, experiences of trauma become the curriculum |

| PRAXIS (EXAMPLES) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TO | FOR | WITH | BY | AS |

| Multisection mathematics course, unified assessments/ curriculum, but educator takes account of of previous learner’ struggles/needs and creates flexible deadlines and culturally relevant examples and authentic assessments (all educator pre-defined) | Multisection business course, but educator has some leeway over assessments but not learning outcomes. Surveys learners at the beginning of the semester and selects options of assessment based on learner interests and needs. Educator pre-defines different options and negotiates some deadlines and such with learners. | Elective course where educator has freedom over learning outcomes and assessments Educator always in negotiation with learners over learning outcomes and assessments BUT educator sets the “rules for engagement”, facilitates the discussion, and makes final decisions. Educator can negotiate grading criteria and grades with learners, but ultimately holds power over final grades | Co-curricular community-based learning course with an educator as “advisor” but learners lead in terms of where to go, what to do, how to do it. Learners decide on grading criteria, but an educator still officially sets a grade | Extracurricular activity, completely learner-led

Community engagement / Adult Education settings. Educators not involved in assigning a “grade” at all |

Table 1: Participation levels across Weihipehana’s (2013) model adapted for compassionate learning design

Conclusion

Compassionate learning design involves reflection of and attention to who makes choices in teaching and learning and the implications thereof. We argue that considering the intersecting dimensions of participation, justice, care, and praxis provides a helpful approach to learning design that is both compassionate and critical. In addition to contextual factors that constrain participation levels, designing for learner positionalities is a practice that educators, IDs/LDs, and co-designers of learning opportunities often do not fully understand. Also better understanding one’s own positionality and how this drives particular designs over others is important. When designing in times of uncertainty and flexibility, we believe that educators and learners need to be conscious of intentionality and agility around cultivating compassion. We encourage readers to see this as a developmental and social process that is forever changing as you collaborate with fellow educators, IDs/LDs, and learners and grow your praxis over time.

References

Anvari, F., & Richards, D. (2018). Personas with knowledge and cognitive process : tools for teaching conceptual design. Twenty-Second Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Proceedings. 43. Japan: PACIS. https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2018/43

Bali, M. (2021). Do unto students as they would have done unto them. Times Higher Education Campus. Retrieved March 29, 2022 from https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/do-unto-students-they-would-have-done-them

Bali, M. (2020). Pedagogy of care: COVID-19 edition. Reflecting Allowed. Retrieved March 29, 2022 from https://blog.mahabali.me/educational-technology-2/pedagogy-of-care-covid-19-edition/

Bali, M., Caines, A., Hogues, R., Dewaard, H. & Christian, F. (2019). Intentionally equitable hospitality in hybrid video dialogue: The context of virtually connecting. eLearn Magazine. Retrieved March 29, 2022 from https://elearnmag.acm.org/archive.cfm?aid=3331173

Bali, M., & Zamora, M. (2020). Equitable emergence: Telling the story of #EquityUnbound in the open. #OpenEd20 Plenary. Retrieved March 29, 2022 from http://youtu.be/NEeZvM6_8UE

Bali, M. & Zamora, M. (2022) .The Equity-Care matrix: Theory and practice. Italian Journal of Educational Technology. https://ijet.itd.cnr.it/article/view/1241

Bali, M. & Zamora, M. (2022). Intentionally equitable hospitality as critical instructional design. In M. Burtis, S. Jhangiani, & J Quinn (Eds.), Designing for care. Hybrid Pedagogy. https://designingforcare.pressbooks.com/chapter/intentionally-equitable-hospitality-as-critical-instructional-design/

Boler, M. (1999). Feeling power: Emotions and education. New York: Routledge.

Borkoski, (2019). Cultivating belonging. Equity & Access PreK-12. Retrieved July 14, 2022 from https://www.ace-ed.org/cultivating-belonging/#:~:text=Who%20does%20it%20benefit%3F,Walton%20%26%20Carr%2C%202012.

Bradshaw, A. C. (2017). Critical pedagogy and educational technology. In A. D. Benson, R. Joseph & J.L Moore (Eds), Culture, Learning and Technology (pp. 8-27). New York: Routledge.

Costa, K. (2020). Trauma-Aware teaching checklist. 100 faculty. Retrieved March 29, 2022 from https://bit.ly/traumachecklist

Costanza-Chock, S. (2018). Design justice: towards an intersectional feminist framework for design theory and practice. Proceedings of the Design Research Society. Limerick: DRS. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3189696

Czerniewicz, L., Agherdien, N., Badenhorst, J., Belluigi, D., Chili, M., Villiers, M. de, Felix, A., Gachago, D., Ivala, E., Kramm, N., Madiba, M., Mistri, G., Mgqwashu, E., Pallitt, N., Prinsloo, P., Solomon, K., Strydom, S., Swanepoel, M., Waghid, F., & Wissing, G. (2020). A wake-up call : Equity , inequality and COVID-19 emergency remote teaching and learning. Postdigital Science and Education, 2(3), 946–967. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42438-020-00187-4?fbclid=IwAR3dWEIwpRz4r7ox3izGoj64g1Flee6eJT0IDOQg42MuPkl1R7211mc7Y0M

EquityXDesign (2016). Racism and inequity are products of design. They can be redesigned. Medium. Retrieved March 29, 2022 from https://medium.com/equity-design/racism-and-inequity-are-products-of-design-they-can-be-redesigned-12188363cc6a

Fraser, N. (2005). Reframing Justice in a globalized world. New Left Review, 36 (Nov/Dec). Retrieved March 29, 2022 from https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii36/articles/nancy-fraser-reframing-justice-in-a-globalizing-world

Freire, P. (1970/2005). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group.

hooks, b. (2003). Teaching community: A pedagogy of hope. New York: Routledge.

hooks, b. (2014). Teaching to transgress. New York: Routledge.

Imad, M. (2021). Transcending adversity: Trauma-Informed educational development. To Improve the Academy, 39(3). Retrieved March 29, 2022 from https://quod.lib.umich.edu/t/tia/17063888.0039.301?view=text;rgn=main

Imad, M (2020). Leveraging the neuroscience of now. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved March 29, 2022 from https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2020/06/03/seven-recommendations-helping-students-thrive-times-trauma

Gachago, D., Van Zyl, I. & Waghid, F. (2021). More than delivery: Designing blended learning spaces with and for academic staff. In Sosibo, L. & Ivala, E. (Eds.), Transforming learning spaces (pp. 132-146). Vernon Press.

Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a design science: Building pedagogical patterns for learning and technology. Routledge.

Ngoasheng, A., Cupido, X., Oyekola, S., Gachago, D., Mpofu, A., & Mbekela, Y. (2019). Advancing democratic values in higher education through open curriculum co-creation: Towards an epistemology of uncertainty. In L. Quinn (Ed), Reimaging curricula: spaces for disruption, p.324-44. African Sun Media. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198294719.001.0001

Noddings, N. (2012). The language of care ethics. Knowledge Quest, 40(5), 52-56.

Pacansky-Brock, M. (2020). How and why to humanize your online course. Retrieved March 29, 2022 from https://brocansky.com/humanizing/infographic2

Segal, E. (2007). Social empathy: A tool to address the contradiction of working but still poor. Families in Society, 88 (3), 333–37.

Sentiles, S. (2017). We’re going to need more than empathy: We have to get radical with the idea of the other. LitHub. Retrieved March 29, 2022 from https://lithub.com/were-going-to-need-more-than-empathy/

Silverman, S., Caines, A, Casey, C., Garcia de Hurtado, B., Riviere, J., Sintjago, A., & Vecchiola, C. (2021). What happens when you close the door on remote proctoring? Moving toward authentic assessments with a people-centered approach. To Improve the Academy, 39(3). https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0039.308

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. (HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884). US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved March 29, 2022 from https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

Tronto, J. C. (2015). Who cares?: How to reshape a democratic politics. Cornell University Press.

van Zyl, I. & de la Harpe, R. (2014) . Mobile application design for health intermediaries. Considerations for information access and use. BIOSTEC 2014: Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies, 5, 323–328. https://doi.org/10.5220/0004800803230328

Walker, M., & Unterhalter, E. (2007). Amartya Sen’s capability approach and social justice in education. Palgrave Macmillan.

Wehipeihana, N. (2013). A vision for indigenous evaluation [Keynote conference presentation]. Australasian Evaluation Society Conference, Brisbane, Australia. https://youtu.be/H6LXD3RjqLU

White, J. A., & Tronto, J.C. (2004). Political practices of care: Needs and rights. Ratio Juris, 17(4), 425-453.

Zembylas, M. (2008). Engaging with issues of cultural diversity and discrimination through critical emotional reflexivity in online learning. Adult Education, 59 (1), 61–82. http://adlawrence.blogs.wm.edu/files/2011/03/cultural_diversity_emotional_reflex.pdf

—. (2011). The politics of trauma in education. Palgrave Macmillan.