Domain V: Collaborate with Clients to Apply a Contextualized, Systemic Lens to Case Conceptualization

CC14 Case Conceptualization

Position client presenting concerns and counselling goals within the context of culture and social location.

Recommended Reading

Collins, S. (2018). Collaborative case conceptualization: Applying a contextualized, systemic lens. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 572–601). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Core Competency 14 of the CRSJ counselling model (Collins, 2018) emphasizes that cultural identities and social locations can have a significant influence on how clients view their problems and their preferred outcomes. The CRSJ counselling model draws on various epistemological and theoretical lenses to support an approach to practice intended to foster holistic and multifaceted case conceptualization. The intent is to respect and appreciate diverse views of health and healing, including those of the learner (Bemak & Chung, 2017). It is also important to assess clients’ personal theories of change and preferred outcomes or futures to ensure that both counselling goals and change processes are congruent and meaningful within their worldviews (Arthur & Collins, 2015). A counsellor superimposing their own lens on what is either possible or preferable, even inadvertently, may be experienced as cultural oppression by their client. It may also result in missing critical information from the contexts and systems in which clients function. These broader systems are often a significant part of the problem and a logical focus of intervention. Central to the CRSJ counselling model is the application of a contextualized, systemic, and social justice lens to case conceptualization to assess actively the locus of control of client presenting concerns (Ratts & Pedersen, 2014).

CRSJ Counselling Key Concepts

The activities in this chapter are designed to support competency development related to the key concepts listed below. Click on the concepts in the table and you will be taken to the related activities, exercises, learning resources, or discussion prompts.

|

Collaboration on Goals/Processes

On-target, off-target goals and processes (Partner or small group activity)

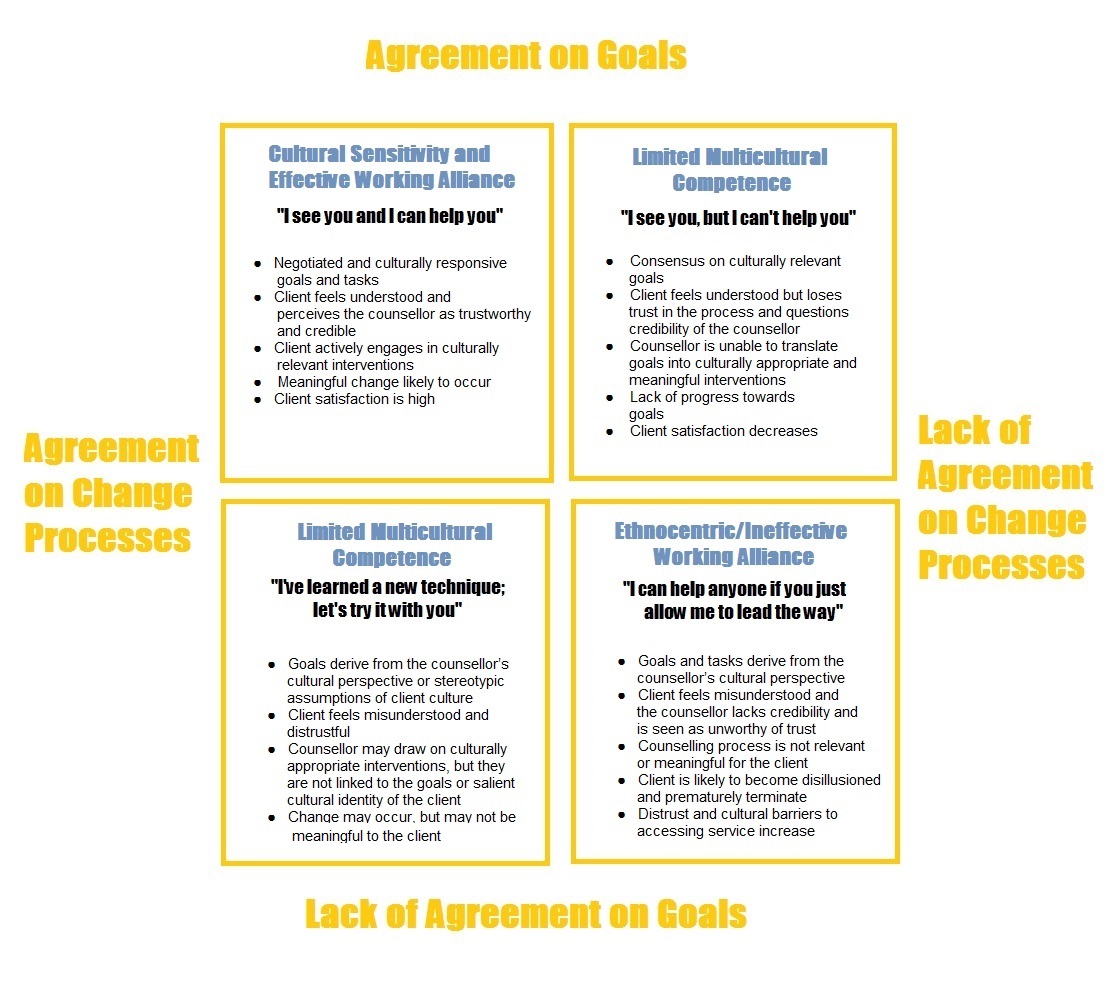

An effective working alliance requires that counsellors and clients collaborate on the goals of counselling and the change processes to reach those goals. Failure to do so can result in goals and processes that are not culturally responsive and, in some cases, reflect an imposition of values that reflect social inequities. To reflect on how collaboration on the goals and processes of counselling is positioned within the CRSJ counselling model, consider the figure below, which provides an explication of potential mismatches when the counsellor and client(s) don’t align on the goals and processes of counselling. For easier viewing on smaller screens, right click on the image and open it in a new tab.

Consider the following mismatches.

- On-target goals, off-target processes

- Off-target goals, on-target processes

- Off-target goals, off-target processes

Individually, come up with a client scenario to illustrate each of these situations. Then, work together to compare your scenarios for common themes or divergent perspectives. Reflect on the potential effects of these mismatches on both clients and counsellors. Finally, identify three principles or practices related to building a culturally sensitive and socially just relationship with clients that might prevent these mismatches from occurring in the first place; that is, support on-target goals and on-target change processes.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc14/#ontarget]

Co-constructing goals by leading from behind (Class discussion)

Ultimately, it is the client’s preferred outcomes that are prioritized through the counsellor‒client collaboration on goals and change processes. However, this may not be as simple as asking clients what they want. The process of working towards shared understanding and agreement on counselling goals often requires skillful, compassionate, and culturally responsive work on the part of the counsellor to guide the collaborative process and define goals that are a good fit for the client and which are appropriate to our professional practice values and standards. Consider one or the other of the following scenarios:

Joe comes to counselling because he is court-mandated to attend anger management sessions. He has a history of aggressive behaviour towards female partners and, most recently, pulled a knife on his current commonlaw partner. Joe’s first question is what he has to do to get the court off of his back. He responds to your questions with yes/no answers wherever possible and is watching the clock for most of the session. You can sense your frustration building as Joe continues to deflect responsibility for his actions. He holds firm to the belief that his partner provokes him and is, at least, equally responsible for the mess his is now in.

Fatima is feeling stress about her upcoming marriage to a man selected for her by her parents. She has not met him. He will be arriving in Canada within the next month, and they are to be married shortly thereafter. She is pleased with the selection that her parents have made for her. So, at first, it is difficult to tell what it is that is causing Fatima’s distress. She tells you that she had a injury as a young girl, and she is worried that it might affect her new husband’s acceptance of her. She has no visible disfigurement. However, she is insistent that she needs your help to find a doctor to help her. It is not until the second session that she reveals that her older brother came to her bed regularly starting when she was 7 until she turned 15. She wants to find a doctor to “sew her back up,” so that her “sins” are not visible to her husband. Otherwise, she will bring shame on the whole family.

Critique the principles, techniques, or relational strategies that might help you work with either Joe’s preferred outcome of getting the court off of his back or Fatima’s desire to erase evidence of her sexual abuse while moving toward counselling goals that reflect active collaboration between counsellor and client, respect for client worldview and values, and your professional practice values and ethics.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc14/#coconstructinggoals]

Conceptualizing Client Lived Experiences

Please take a moment to view the video below in which I share some of my thinking related to this domain in the CRSJ counselling model. I have been considering critically the language commonly used in counselling practice, and I have moved away from case conceptualization terminology in favour of conceptualizing client lived experiences. I explain some of my shifts in language use in this video.

As you move through your day, as a student, a counsellor, an instructor, or a supervisor, pause to reflect on the language you are using or encountering in your educational or professional circles. How might this language and the particular lenses from which it derives affect the ways in which you are thinking about, and making sense of, your clients’ lived experiences?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc14/#conceptualizingframework]

Conceptualizing client lived experiences: Applying a CRSJ lens (Self-study)

Consider the story of Anika (introduced below) from the perspective of the bio–psycho–social–cultural–systemic framework on conceptualizing client lived experiences. As you listen to Anika’s story, write down as many questions as you to guide your inquiry into their lived experiences. Attend to how these curiosities may support your work together to co-construct a shared understanding of the challenges Anika faces.

In this next video I replay Anika’s story, pausing periodically to share my own reflections and to introduce areas of cultural inquiry that might support me in more fully understanding Anika’s experience. Notice how the questions I pose move beyond the traditional bio–psycho–social model of case conceptualization to embrace the cultural and systemic influences on Anika’s story.

How might the CRSJ counselling model enhance client–counsellor co-construction of understanding of client challenges as a foundation for envisioning preferred futures and coming to agreement on change processes that are inclusive of cultural and systemic dimensions of client lives?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc14/#CRSJconceptualizing]

Contextualized/Systemic Lens

Watch the following short YouTube video.

Reflect on the ways in which Aamer Rahman applies a contextualized/systemic lens to frame his understanding of reverse racism. Engage in a dialogue with your peers focusing on

- the implications of this systemic perspective on racism for recognizing and negotiating power and privilege within the client–counsellor relationship and

- the necessity of assuming a contextualized/systemic lens at all points in the counselling process.

What are the challenges in holding this lens? What are the potential risks of not embracing this positioning?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc14/#reverseracism]

Positioning trauma in context: Complex post-traumatic stress

To a large degree, trauma and its effects have been interpreted through a eurowestern individualist lens, meaning that the focus is on specific traumatic incidents experienced by particular individuals. To appreciate the difference between post-traumatic stress (PTS) and complex post-traumatic stress (complex PTS), you must apply a systemic and contextualized lens. Watch the first 3:22 minutes of the video below as an introduction to complex PTS.

Then reflect on the following questions:

- Attending to current events, how might you apply a contextualized/systemic lens to better understand the lived experiences of persons or peoples experiencing colonial or political violence and other forms of systemic oppression?

- How might positioning the impacts of trauma from within this systemic lens support different approaches to addressing trauma and and its impacts at the cultural or community levels?

- What are the implications of complex PTS for working with individual clients who may be impacted by these broader cultural, community, and systemic forms of violence and oppression?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc14/#cpts]

Cultural Appropriation–Cultural Appreciation

Watch the YouTube video by Rosanna Deerchild from the CBC radio show, Unreserved.

© CBC, Unreserved radio Indigenous, n.d.

As you reflect on this video, which speaks to appreciation and respect for cultural artifacts, think about how much more important it is for counsellors to avoid appropriation of cultural and spiritual rituals, practices, knowledge, and worldviews. Revisit the concept of psycholonization , and reflect critically on how you can translate these cautions about cultural appropriation into 2–3 basic principles that will help you discern how to be responsive to client cultural contexts and identities without engaging in psycholonization or cultural appropriation.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc14/#whatisyours]

Indigenous methods of healing are gaining popularity in professional and public domains. The use of indigenous healing approaches within counselling is one of those challenging ethical and cultural sensitivity areas that does not have clear boundaries. It is important to consider multiple factors and to engage in complex ethical decision-making before drawing on these practices in your own work.

Engage in a debate about this issue. If your last name starts with A‒M, you must argue against the use of these practices by non-Indigenous counsellors; if your name starts with N‒Z, you must argue for the use of these practices by non-Indigenous counsellors. Please be very specific about the how, why, and with whom of their use in your arguments.

Toward the end of the discussion, please share your own personal and professional positioning on this issue, drawing on key points in the discussion.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc14/#useofhealingpractices]

Indigenous Views of Health and Healing

[Adapted from the contribution by Art Blue, Wes Darou, and Carlos Ruano]

This learning activity invites you to apply your learning about Indigenous peoples to the counselling process, in particular the process of developing cultural understanding of indigenous views of health and wellness. Invent an imaginary First Nations, Inuit, or Métis couple. Conduct the necessary research to support your ideas, and to avoid unfounded stereotypes. Attempt a degree of rich detail to describe the physical aspects of their life, such as geographical location, their home, family composition, and day-to-day activities. Write a three-paragraph short story about them, attending in particular to what a healthy life might look like for them. Then complete the Indigenous Views of health template (MS Word version) to extend your understanding in way that would support culturally responsive goal setting.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc14/#createastory]

Views of Health and Healing

One of the foundational skills in counselling is the ability to listen actively, attentively, and patiently to our clients. However, there is a natural tendency in our listening to apply our own culture-centric lens to what and how we hear client stories. Listening across cultures requires an openness to receiving meaning from clients in ways to which we may not be accustomed. In many cultures, people express their emotional distress in what might be seen, through a Eurocentric lens, as indirect ways. For them, however, the communication is clear, and the problem is with the listener. Consider the following client stories. Place yourself in the room with these clients, and attend to your emotional and cognitive reactions. If you do not hold an individualist worldview, listen for what resonates for you and attend to cultural differences and similarities.

This is your first session with Andrei. He immigrated to Canada from Moldova three years ago, with his wife and three small children. As a young man, he spent six months in the United States, living with a Moldovan family, to learn English. He is still most comfortable speaking Romanian, but does not require an interpreter. Andrei is telling you a story about his job. He is having difficulty fitting in with his work team. One day he woke up and Pacala offered to go to work with him to charm his colleagues. At lunch Pacala told a few jokes and poked fun at himself, but his colleagues still kept him at a distance. The next day, Fat Frumos was sitting at the end of his bed when he woke up. Andrei smiled anticipating a better day. Fat Frumos sat beside him during his weekly meeting with his supervisor and poured on the charm, telling stories of his latest conquest, a particularly hostile dragon. Andrei turns with a look of disheartenment and says, I’ve always counted on Pacala and Fat Frumos. Now even they have let me down.

Himari is a recent university graduate, who is a second generation immigrant from Japan. You have been working with her for a number of months doing career counselling. She has just announced that she was the successful candidate for an engineering position in a company at which she really wants to work. You are delighted for her and immediately leap up to do a happy dance. Himari smiles but remains quiet, calm, and almost solemn. You immediately adjust your affect to mirror hers, sitting back down and looking at her seriously. She seems surprised and asks you why you are no longer happy for her.

Serwa is a middle-aged, female refugee from Ghana. In her first session, she explains, using an interpreter, that she has been in constant pain since she left Ghana three months ago. She has a very stiff neck and describes a lack of sensation and weakness in her hands. As the interpreter communicates this to you, Serwa goes limp in the chair with her neck falling forward and her arms hanging at her sides. You respond with alarm; however, she quickly returns to normal and looks at you expectantly. You ask a few questions, through the interpreter, about her transition to Canada, her social support network, and her level of acculturative stress. After listening to Serwa for a few moments, the interpreter says that Serwa’s teenage daughter also has similar symptoms, although they only started a few weeks ago. Serwa is grateful to you and wonders if she can bring her to the next appointment with you, the doctor.

Depending on your own cultural heritage, you may be more or less familiear or bewildered by these stories. Attend to your reactions and consider carefully both what you might choose for your immediate, in-the-moment responses to these clients and what between-session research and consultation might best prepare you to provide culturally responsive services.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc14/#listening]

References

Arthur, N., & Collins, S. (2015). Culture-infused Counselling and Psychotherapy. In L. Martin, B. Shepard, & R. Lehr (Eds.), Canadian counselling and psychotherapy experience: Ethics-based issues and cases (pp. 277-303). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Bemak, F., & Chung, R. C. (2017). Refugee trauma: Culturally responsive counseling interventions. Journal of Counseling and Development, 95(3), 299. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12144

Collins, S. (2018). Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology. Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Ratts, M. J., & Pedersen, P. B. (2014). Preface. In M. J. Ratts & P. B. Pedersen (Eds.), Counseling for multiculturalism and social justice: Integration, theory, and application (4th ed., pp. ix-xiii). American Counseling Association.