Domain VI: Implement and Evaluate Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Change Processes

CC16 Microlevel Change

Engage in culturally responsive and socially just change processes at the microlevel (i.e., individuals, couples, and families) in collaboration with clients.

Recommended Reading

Collins, S. (2018). Culturally responsive and socially just change processes:

Implementing and evaluating micro, meso, and macrolevel interventions. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 689–725). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Core Competency 16 of the CRSJ counselling model (Collins, 2018) addresses microlevel interventions in which the focus of change is on the individual client, the couple, or the family. Even when it is most appropriate for learners to collaborate with clients to co-construct change processes at the microlevel, a contextualized and systemic lens on intervention is essential (Winslade, 2018). Each microlevel intervention below supports cultural responsivity and takes into account the lived experiences of marginalization, othering, cultural oppression, and other forms of social injustice that clients may encounter. Both the direction for and the process of implementing change occur in collaboration with the client. The list of microlevel interventions below is certainly not exhaustive; rather, it emerged through my own research and my review of case studies related to multicultural counselling and social justice. I encourage learners to continually expand their repertoire of change processes to support CRSJ counselling practices.

The first few microlevel change strategies focus on pragmatic supports, often positioned outside the scope of practice of counsellors; however, addressing these social determinants of health is often essential with clients who face multiple marginalization (Rimke, 2016). Then I introduce a number of interventions that draw on feminist and Indigenous practices to collaborate with clients to critically analyze these social determinants of health through consciousness-raising, deconstruction, or decolonization. The narrative therapy processes of storying and re-storying support clients’ reconstruction of cultural identities and relationalities. With Indigenous clients, integration of Indigenous practices may enhance identity reconstruction. The next cluster of change processes calls forth the ways in which clients continue to successfully navigate their lives and care for their own needs, even in the face of sociocultural oppression and reminds learners of the need for a deep commitment to affirming diversity and social justice in practice. Clients with multiple, intersecting, nondominant identities may also benefit from support in reconciling conflicting values, cultural identities, and sociocultural contexts.

CRSJ Counselling Key Concepts

The activities in this chapter are designed to support competency development related to the key concepts listed below. Click on the concepts in the table and you will be taken to the related activities, exercises, learning resources, or discussion prompts.

Affirmative Practice

Communicating affirmation moment-by-moment (Self-study or partner activity)

Consider the conversations below between counsellor and client below. Draw on the skills of critical thinking, cognitive complexity, reflective practice, and cultural humility to critique these interactions from an affirmative practice perspective (Singh & Dickey, 2017). These conversations go in entirely different directions based primarily on the assumptions and values positioning of each counsellor.

Conversational microaggressions are subtle, commonplace, and often insidious violations of a person’s dignity, intentional or unintentional. They can be incredibly harmful to clients when they are part of counselling conversations. In the first video the counsellor responds in ways that do not affirm the dignity of the client, potentially negatively affecting their health and well-being. In Part II below the counsellor engages in affirmative practice with the client. Affirmative practice involves actively validating client’s cultural identities and challenging all forms of cultural oppression. In this video the counsellor demonstrates respect for the client’s perspectives and inherent worth through culturally responsive language.

Once you have carefully reviewed these two counsellor–client dialogues, write a list of 4–5 questions or statements that you might use in your initial conversations with new clients to communicate an affirmative practice stance. If this seems too abstract, you might want to envision a client with whom taking an affirmative stance would be particularly difficult and make the questions or statements specific to them. How might you adjust your approach if you were working with a child? What adaptations might be necessary to communicate these messages when working with someone with a cognitive disability? Next, create a checklist of other contextual factors (e.g., the counselling environment, the intake process, the accessibility or range of services) that you might want to consider before you even meet a client, because they can also communicate messages about cultural safety. You may want to debrief this activity with a peer to see what they identified as examples of non-affirmative and affirmative practices.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#affirmation]

Decolonizing

Building change processes based on a decolonizing praxis (Self-study)

Consider the definition of decoloning praxis by Hellson (2015, para. 3) of the WAVAW Rape Crisis Centre: “Decolonization is unlearning Colonization . . . it’s changing the conversation from ‘us and them’ to ‘we’.” Then watch the video created by this organization to demonstrate how a decolonizing approach can be integrated into all forms of service delivery with Indigenous peoples. This decolonizing anti-violence approach to survivors of sexual violence supports Indigenous clients to access services and resources in ways that are meaningful to them, demonstrate respect for dignity, and draw on community connections. As you watch the video, make a list of principles or practices that support decolonization.

Consider the organization where you currently work (or imagine the context of your future counselling practice). Apply your list of decolonizing practices or principles to this context. Be as specific and practical as you can to bring this concept to life and to reinforce your learning.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#decolonizingpraxis]

Honouring Indigenous culture and spirituality (Class discussion)

Many of the principles for working with Indigenous peoples are drawn from their unique values and worldview, which are grounded in Indigenous spirituality.

- For non-Indigenous participants, examine critically how you might extricate yourselves from the oppressive legacies of your own cultures and spirituality or religions to create space to fully honour Indigenous cultural and spirituality in our counselling practices? How might you sensitize yourselves to the continued processes colonization in counselling and psychology practice so that you can interrupt ongoing psycholonization of Indigenous clients?

- For Indigenous participants, in what ways do you see colonization expressed through the presenting concerns of your clients? What healing principles or practices, either traditional or Western, are most helpful in raising consciousness about the lingering effects of colonization with your clients?

Be very specific in identifying potential examples of psycholonization carried forward by uncritical examination of worldviews and suggest ways these could be addressed and/or alternative assumptions or practices brought to the fore. Together, generate a set of draft principles that you might use in your own practices.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#honouringspirituality]

Deconstruction

The process of deconstruction is common to feminist and narrative traditions. Included in the broad umbrella of deconstruction are gender role analysis, power analysis, and class analysis, for example.

Applying gender role analysis to the intersections of gender and ability (Class discussion)

Before engaging in the class discussion, review the steps in the feminist practice of gender role analysis (adapted from Worell and Remer, 2003).

- Elucidate messages received through gender role socialization.

- Analyze critically the positive and negative consequences of these gendered narratives.

- Reflect on the degree to which these messages have been internalized.

- Select actively from those gendered messages, the ones the client wants to maintain or discard.

- Co-construct change processes to facilitate these preferred outcomes.

Then, reflect critically on the vignette below.

Anna is a professional athlete competing in events on both the national and international level. She presents as bright, articulate, and confident. She changed the focus of her athletic endeavors following a serious ski accident eight years ago, in which she broke her back and lost the use of her legs. She now competes as a snow boarder in paraplegic events.

She talks comfortably about her accident and the process of rebuilding her life. She has lots of social supports and resources. She has been completing her graduate education in health studies, while training rigorously for upcoming sporting events.

When you ask what has brought her to the counselling session, she hesitates and then explains that she is struggling to get back into dating. She has a lot of positive relationships with male friends, but even if she is interested in something more, things never seem to move in that direction. She seems to have become “one of the boys,” which she enjoys, but this is not enough. Before her accident, she had no difficulty in this area, and always had a boyfriend or a number of guys that she was dating casually.

Anna notes that most of her current social relationships revolve around sports, and the athletes involved in the paraplegic games are predominantly men. She does have a few close female friends who are very supportive, but she has not talked with them in depth about her concerns.

Work together as a class to apply the principles of gender role analysis to your discussion, based on the following prompts:

- In what ways might the gendering of professional sports and of women with disabilities come into play in this scenario?

- How might the intersections of gender and ability be playing out in Anna’s lived experiences?

- What broader sociocultural discourses related to gender and ability might you consider exploring with Anna?

- What types of gendered assumptions might you need to attend to so that you don’t bring them forward into your relationship with Anna?

- How might this analysis of gender support Anna in moving forward with her goals?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#genderability]

Applying power analysis to the intersections of age and religion (Partner activity)

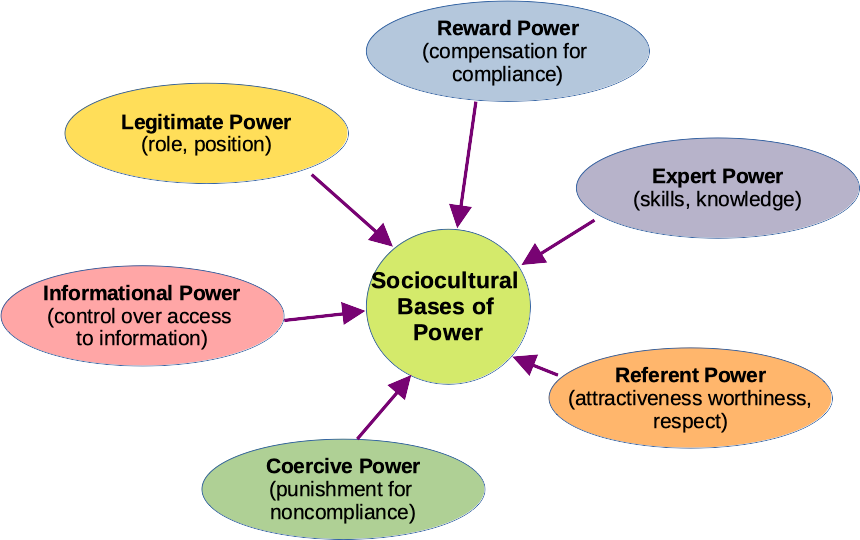

To begin talking with clients about power, it is helpful to understand the different types of power, which are most often tied to the work of French and Raven (1959) and Raven (1965), first introduced in CC5. Consider the brief descriptions provided below.

Now, let’s apply our understanding of power to a client scenario. Each person should make up a story that demonstrates how power might play out for Sarah. Be creative and extend this story in any direction you like.

Sarah is 79 years old. She lives on her own with three cats in a small bungalow in the inner city. Sarah’s husband died three years ago. Both of their parents narrowly escaped the Holocaust in Germany. They never had any children.

Share your stories with each other, and apply the following steps in power analysis, adapted from Worell and Remer (2003).

- Engage the client in critical analysis of the nature and basis of power.

- Examine together differential access to various types of power, including the influence of cultural identities/relationalities and social location.

- Encourage deconstruction of the ways in which sociocultural narratives, social norms, experiences of cultural oppression, and intersections of various *isms have influenced the client’s access to, and internalization of, messages related to the use of power.

- Engage in a cost-benefit analysis to empower client agency in self-selecting personal power strategies they want to either to foster or eliminate.

Reflect critically on how the differences in your stories impacted the application of power analysis. Step back to consider how your own position of power within the client–counsellor relationship may have influenced the direction of your stories or the process of your analysis.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#agereligion]

Empowerment/Self-Empowerment

Visualization: Kicking Down the Mirror (Partner activity)

[Contributed by Gina Wong]

This activity is something you can do with a partner, suggest to a client, or imagine for yourself. Identify a judgment or criticism you or others are feeling in the moment and follow these visualization steps:

- Describe a context in which you experience that judgement or criticism.

- Visualize the details of that situation. What do you anticipate from others? What do you experience in the moment?

- Invite the judgment or criticism into full awareness including mind, body, and emotions.

- Imagine that you are standing in front of a full-length mirror and picture the negative, bad self you reflected in the eyes of your critics. Let yourself feel the judgment or criticism in the moment.

- Use your full force to kick and smash the mirror with your legs (you may actually want to stand up and physically kick down the metaphorical mirror).

- Watch the glass explode and see the judgement and self-criticism shatter and fall away.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#visualization]

Empowerment for Self-Advocacy

One of the core principles of CRSJ counselling is to adopt a contextualized, systemic lens to assess the locus of control or responsibilty for the challenges that clients face (i.e., the source of the challenge) and locus of change (i.e., most effective starting point for change). In some cases, the best course of action is to support clients to change those contexts of their lives at the micro (i.e., individuals, couples, families), meso (i.e., schools, organizations, or communities), and sometimes even at the macro levels (i.e., broader social, economic, or political systems). I have adapted the steps in the empowerment for self-advocacy strategy from the American Counselling Association: Advocacy Competencies by Lewis and colleagues (2003) below, adjusting the language to reflect the CRSJ counselling model.

- Work together with the client to assess their strengths, competencies, and resources.

- Engage in constructive collaboration with the client to identify challenges or barriers resulting from systemic or internalized oppression.

- Co-construct a thick description of the systemic factors that affect the client, most typically at the micro or meso levels.

- Support the client to identify their preferred futures and to co-construct goals.

- Educate the client in self-advocacy skills.

- Co-construct self-advocacy action plans with the client.

Consider the following client story.

Karen works in an office building on the outskirts of the downtown core. She is often required to work late, and finds herself walking home in the dark on nearly deserted streets. Recently, she has encountered a number of people asking for money or calling to her from doorways. There is no easy access to transit, and it is quicker to walk home. However, she is finding it increasingly stressful to be alone on the streets at night.

She does not have the same experience in the early mornings, but her request to shift her hours of work was denied by her immediate supervisor. She has adopted a few new strategies (e.g., carrying a flashlight, talking to her partner on the phone, taking different routes), but she is still uneasy. She is also reading in the local news more about the challenges faced by the unhoused and those living in poverty in the downtown core. She realizes that the pandemic has increased the barriers to resources many people face.

Based on this scenario come up with two potential change agendas at the contextual level that might fit for Karen’s challenge. Then identify several self-advocacy skills that you might introduce to empower Karen to effect change in one or more contexts or systems.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#selfadvocacy]

Externalizing

Drawing and interviewing the problem (Self-study)

[Contributed by Gina Wong]

I often use an externalizing technique from narrative therapy to shift clients’ understanding and relationship with the problem. I invite the client to first draw and then interview the problem. When working with a client, emphasize that there is no right or wrong way to do it. Nor is there any judgement on the quality of the drawing. The idea is to remove as much stress related to perfectionism from around this activity as possible. Let the client know that their drawing could include abstract or more concrete representations and that it is completely up to them. Follow these steps to try out the activity yourself:

- Gather a few pieces of blank paper (in case you wish to draw more than one picture or want to start over). Provide crayons, markers, color pencils, and watercolour paint and brushes so there are options for various media.

- Get in touch with the problem you are experiencing. Attend to your feelings. Close your eyes and tune into your body.

- Create an image of the problem (If you are doing this with a client, stay quiet so that the client can focus on drawing. It may help to play some very soft, relaxing music if a client would benefit from this addition.)

- Once you have finished the drawing, choose a title for it. (For example, clients have chosen titles such as “Doom” or “Crazy Brain” or “Black Abyss.”)

- Prop the drawing onto a third chair so that you can see the image.

- Then interview [insert name of the drawing] and answer as if you are speaking for [insert name of drawing]. Some questions may not have answers and are used for reflection. Here is a list of common interview questions that may facilitate shifts in your experience and relationship with the problem:

- [Name of drawing], what is the first and smallest sign that you are present in [client]?

- [Name], when did you first enter [client’s] life?

- [Name], were there small seedlings of you even earlier in [client’s] life?

- [Name], in what ways do you serve [client]?

- [Name], in what contexts are you most likely to come to the forefront in [client’s] life?

- [Name], are there things that happen that decrease your presence in [client’s] life?

- [Name], are there things that happen that increase your presence in [client’s] life?

- [Name], what cultural discourses, images, or stories bolster your power in [client’s] life?

- [Name], what would happen to [client] if you disappeared?

Externalizing questions such as these treat the problem outside of the client rather than as an internal flaw. It can stimulate conversations about the problem in creative ways that provide novel insight to client’s experiences.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#drawingtheproblem]

Negotiating Multiple Nondominant Identities

Meet Nathi, a first-generation immigrant from central Africa. She and her husband, Chimaobi, immigrated to Canada through the support of a Christian NGO that helps believers facing persecution in war-torn countries migrate to Canada. Nathi is an extrovert. She immediately makes friends in both her cultural community and among the women she works with at the hair salon in town. She has become part of a women’s group attached to a liberal Christian church that is addressing poverty and homelessness in the area.

Nathi has blossomed in this new environment and is discovering strengths and skills she didn’t realize she possessed. However, as she moves away from more traditional and culturally defined gender roles, Chimaobi has noticed, and this is creating tension in their relationship. He has become verbally abusive and aggressive in trying to prevent her from participating in these activities. As she finds herself increasingly alienated from her new friends and colleagues as a result, she slips into depression, has difficulty sleeping, and starts to experience panic attacks. She is torn between the expectations of her cultural and traditional faith practices and her experiences and opportunities in this new world.

How might you go about helping Nathi to resolve her ambivalence and navigate the tensions between old and new worlds? In a situation where there is potential abuse or violence, most counsellors would not see the couple together, at least initially, so assume you are working alone with Nathi at this point. Critique the practices you come up with and those of your peers carefully in terms of cultural responsivity and social justice (noting any potential tensions between these foundation principles).

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#tensions]

Pragmatic Support

As we shift the lens for defining client presenting concerns and envisioning change processes to include the contexts of clients lives, we are faced with the need to think outside the box in terms of our professional identity and roles as counsellors. Consider the story of Jason below.

Jason has just turned 18. At a time when many of his friends are celebrating their rite of passage into more independence and freedom, Jason suddenly finds himself staring ahead at a mountain of obstacles just to survive on a day-to-day basis. Jason has just completed high school where he was actively involved on the student council, was one of the popular guys, and excelled academically. He has been accepted into several universities locally and away from home. However, on his 18th birthday, he is considered an adult, and he loses access to almost all of the services that have helped him thrive as a young person with a disability. At high school, he has had an aide with him full-time, and a disability services van picks him up in the morning and takes him home at night. He has had access to a physiotherapist within the school who works with him one period per day. As he watches his friends prepare themselves for the adult world and set their sights on colleges and universities across the country, the reality of his much narrower options begins to sink in. His parents both work in the service industry; they put in long hours to make sure that he and his able-bodied brother have what they need. However, it has been government funding for youth with disabilities that has made it possible for him to attend the local high school with his friends. Now that funding will no longer exist. His dad has also recently become quite ill with emphysema, and it is unclear whether he will be able to continue working. Jason has come to you ostensibly for career and life counselling as part of the transition supports services at the school. However, it is clear from the moment he enters the room that this is not the Jason you are used to; instead he appears deflated, stressed, and noncommunicative. He saw a guy in a wheelchair living on the street on the way to school this morning, and he is suddenly convinced that this is his destiny.

Consider how your role as school counsellor might be influenced by embracing pragmatic support and responsiveness to basic subsistence needs within your repertoire of change strategies. Alternatively, consider how you might be optimally helpful to Jason if you decide not to embrace these broader systems level interventions. In either case, how might you actively engage and empower Jason as a co-collaborator in the change process?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#destiny]

Storying and Re-Storying

Choose a significant event or time period in your life, for example, your graduate school experiences. Take a moment to story this experience. Be as creative as you like, choosing an image, metaphor, fable, or other means to express your experience. Attend to the influences of personal history, cultural identities, family, community, social location, and larger social systems in shaping the narrative of how you came to this place in your life. What is the moral of the story, at least to this point in the journey?

Once you are satisfied with your story, rewrite that narrative. Place yourself in the position of the hero(ine) of the story, or choose another way to shift perspective on the story, without changing the basic story line. What is the moral of this new narrative? Reflect on the implications this new narrative has in terms of your thoughts, beliefs, and emotions. How might the new story influence actions you take in the future?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#mystory]

The fluidity of my story (Partner Activity)

[Adapted from Paré (2013)]

Listen to this short clip from the Ted Talk by Chimamanda Adichie entitled “The danger of a single story.” If you are interested in the full TED talk, you can find it here.

© TED Talks (2009, October 7)

How does this perspective shift how you might potentially look at your clients’ stories? How does it shift your view of your own stories?

Consider some significant aspect of your own life story (perhaps drawing on the My story activity above). Without too much reflection, name each section of the story using the Restorying template (MS Word version). An example is provided below. Be honest with yourself about how you have typically viewed this story as you have looked back over your life.

| Story | Re-storying the past |

Re-storying the present |

Re-storying the future |

|

| Past | Rebellion | Resistance | ||

| Present | Compliance | Finding myself | ||

| Future | Other-directed | Self-directed |

Then generate some alternatives to that narrative, beginning first with Re-storying the past by altering the way in which you name the past. Take some time to engage in a process of deconstruction of your lived experience with your partner to support the process of re-storying. Attend carefully to the sociocultural messages that have shaped the way in which you have themed your story to date. How might you reframe the past? Once you have completed this first step, record how this reshapes the present and the future of this story. Repeat this process with Re-storying the present and Re-storying the future.

Discuss the implications of working with client stories. Consider how you might apply this process of re-storying with your clients.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#fluidstory]

Strengths and Resiliency

Honouring strength, resilience, and courage (Self-study)

[Contributed by Karen Cook]

Watch the YouTube video, Our Lives – The Boy Who Will Never Grow Old.

© Real Stories, n.d.

The video provides insights about young adults living with life-limiting conditions. As you watch the video, notice their strength, resilience, and courage. Within the first 3–5 you should be able to articulate some of the qualities you observe. Pay careful attention to your reactions and feelings to lives lived with profound and progressive disabilities.

Consider the implications for how you approach work with young adults with life-limiting conditions or other clients for whom you may not automatically be inclined to adopt a focus on strengths and resiliency. What limitations in yourself (attitudes, knowledge, skills) do you discover as you reflect critically on what you bring as the observer and listener to these stories.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#honouringstrength]

Social Support

Self-inquiry activity: Enhancing your discernment (Self-study)

[Contributed by Melissa Jay]

Although we are capable of immense personal growth on our own, it is important to have people who can help us celebrate our growth! This exercise is meant to support you in identifying and discerning who those people are, in your precious life.

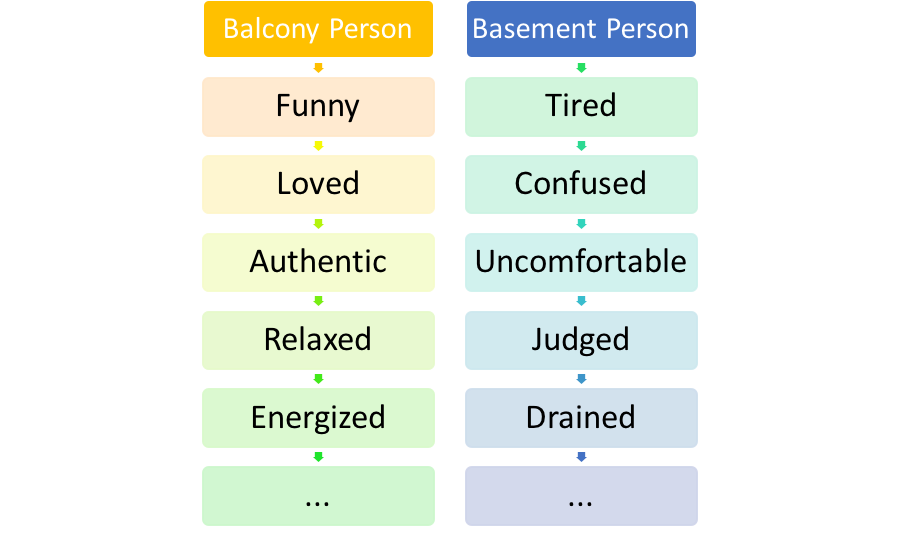

Balcony People

Take a moment to consider the people in your life who light you up. Those are your balcony people. These are people who are there in the good times and bad, and most importantly, they are the ones who remind you of your personal strengths, when you forget.

Basement People

Next, take a moment to consider the people in your life who tend to bring you down. Those are your basement people. They are the ones who will meet you when you are feeling down and out, and they will keep you there. They may also be the ones who question your dreams and abilities.

Exercise

Draw a line down the middle of a piece of paper. On the left side, put the name or initial of a balcony person in your life. On the right side, put the name or initial of a basement person in your life. Now, focusing on one person at a time, close your eyes and tap into how you feel when you are with that person. Open your eyes and list 5–10 words that describe how you feel when you are interacting with your balcony. Then do the same for your basement person.

Take a moment to reflect on these list and to consider the implications for building a network of effective social support. Consider also your own influence on significant others in your life. Finally, how might you ensure that you are a balcony person for every client you work with.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#discernment]

References

Collins, S. (2018). Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology. Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

French, J., & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. Univeristy of Michigan, Institute for Social Research.

Hellson, C. (2015, Oct. 14). A look into decolonizing praxis. Women Against Violence Against Women. http://www.wavaw.ca/a-look-into-decolonizing-praxis/

Lewis, J. A., Arnold, M. S., House, R., & Toporek, R. L. (2003). Advocacy competencies. American Counselling Association. https://www.counseling.org/Resources/Competencies/Advocacy_Competencies.pdf

Paré, D. A. (2013b). The practice of collaborative counseling & psychotherapy: Developing skills in culturally mindful helping. Sage

Raven, B. H. (1965). Social influence and power. In D. Steiner & M. Fishbein (Eds.), Current Studies in Social Psychology (pp. 371–82), Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Rimke, H. (2016). Introduction – Mental and emotional distress as a social justice issue: Beyond psychocentrism. Studies in Social Justice, 10, 4-17. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v10i1.1407

Singh, A. A., & Dickey, L. M. (2017). Introduction. In A. Singh & L. M. Dickey (Eds.). Affirmative counseling and psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming clients (pp. 3-18). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14957-001

Winslade, J. (2018). Counseling and social justice: What are we working for? In C. Audet & D. Paré (Eds.) Social justice and counseling: Discourse in practice (pp. 16-28). Routledge.