9

Betsy Hesser and Hannah Stalter

Introduction

In 1995, the independently filmed documentary “When Billy Broke his Head” won the Sundance Film Festival’s Freedom of Expression award. In it, Billy Golfus, creator of the film and survivor of a traumatic brain injury, documents his experience living with a disability. He details his struggle with social security, with finding employment, and with consistent patronization and belittlement by an able-bodied society. He reveals his battle with mental health problems and suicidality. Golfus’ casual narrative style and witty humor make the harsh reality he is exposing almost palpable. In raw and honest interviews, Golfus reveals the lived experiences of others with disabilities; the blind, quadriplegic, developmentally delayed, among others. He tears down romantic stereotypes. Nothing is sugar-coated. In the film, Golfus states: “Like almost everyone, I thought disabled people were supposed to act tragic and brave, or cute and inspirational, but these people weren’t sticking to the script (Golfus & Simpson, 1995).”

Billy Golfus’ reference to the “script” reflects phenomena of human memory that cognitive psychologists refer to as schemas, or webs of integrated, semantic memory that comprise our knowledge of how the world works (Baddeley, Eysenck, & Anderson, 2020). “Like most people,” Golfus had a knowledge system that expected people with disabilities to behave in a certain way: as tragic heroes, or as cute, comedic sources of inspiration. Schemas are internal representations of the world informed by our cultural context. They are built from the integration of episodic memories, they form the basis of our belief systems, and they direct our future behavior (Wang, Q. & Ross, M., 2007).

Somehow, as a culture, we have created knowledge-webs that link disability to disadvantage, to lesser ability (inherent in the term “dis-able”), and to subhuman qualities. Disability studies researcher Fiona Kumari Campbell echoes this in her definition of ableism, as “a network of beliefs, processes and practices that produces a particular kind of self and body (the corporeal standard) that is projected as the perfect, species-typical and therefore essential and fully human (Campbell, F. K., 2008).” What Campbell describes here is in essence, a biased schema. Thus, in order to understand and combat the issue of ableism, we must understand semanticized memory. We must examine our schemas (i.e., our knowledge-webs); their origin, their makeup, and whether, through difficult processes of re-learning, they can be changed. This series of essays aims to utilize our understanding of memory and the mind, and in doing so, learn how to combat ableism in our thinking and become better, more informed, allies.

Part 1: Cognitive Architecture

Unlike a computer, human minds are not built to be unbiased. Our brains use our life experience to inform our world view, perceptions, and thoughts, and to dictate our decision making. A negative by-product of this unique ability to learn from our past is that we have the potential to become biased beings. While this can help us in many ways, it can also create a culture and society which categorizes certain groups of people as “other” and reinforces systems of oppression. There are many examples of this in our contemporary society, but one which will be discussed throughout this paper is the othering of disabled individuals; more specifically, the formation and reinforcement of “ableism” from the perspective of cognitive psychology.

Although memories might be less reliable than a computer, they are just as capacious, “user friendly,” and far more flexible (Baddeley et al., 2020). As Kleinknecht (2020) says, human brains are built for maximum efficiency, not for accuracy. That is, “we are good at rapidly encoding the context in which an event happens, what happened, when, and where, so as to access when appropriate” as well as being good at noticing and remembering patterns of repeated events which allows us to better understand the world and predict future events (Baddeley et al., 2020). This phenomenon can be explained by Hebb’s Rule which states that, “neurons which fire together, wire together.” The human brain “learns” via neural networks and connections made through experience in our daily lives. From these connections, which according to Hebb are strengthened with each and every use, we make generalizations and assumptions about the world around us which can inform our future predictions, decisions, and reactions.

According to William James, as cited by Kleinknecht (2020), memory is a psycho-physiological phenomenon and recollection of memory and is based on the “law of habit” via associative memory. In other words, the more connections we make from an event to past memories or events, the more likely we are to remember said new information. By using information gathered from our experiences and then translating them into semantic understanding, our minds create systems; otherwise known as “schemas.” These systems (both in the central nervous system and the cognitive system) are shaped by social, political, and cultural systems (Kleinknecht, 2020). This process of learning, in the brain, can be described as “sensitization of cell assemblies via repeated activation” and, in terms of behavior, as “a change in behavior as a result of experience.” As we gain new knowledge from experiences, our behavior, thoughts, and opinions also change and evolve as a result. This is the process by which biases (e.g., ableism) are formed.

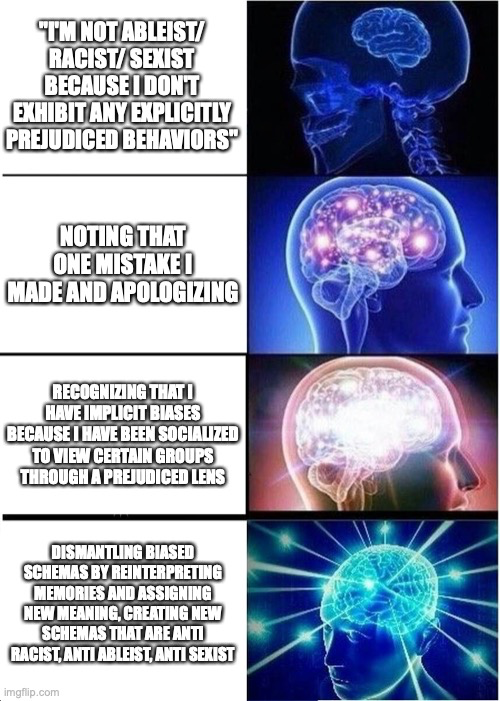

None of us are born sexist, racist, or ableist. Like all elements of culture, these are learned systems, a result of many sensitized neural circuits. Each time the pathways that associate disability with negative stereotypes are activated, the probability that these biased pathways will reactivate in the future increases. For example, multiple episodic memories of disabled comedic side characters in movies, or villains with physical deformities, integrate to create schemas that associated disability with comedy or villainy. With each belittling representation of disability we see, the biased association becomes stronger.

With continued experience, representations of individual events form a foundation for more generalized semantic knowledge about the world (van Kesteren, Brown, & Wagner, 2018). This generalized information, or schemas, are defined as a “structure that people use to organize current knowledge and provide a framework for future understanding” (van Kesteren & Meeter, 2020). Because schemas are informed by our experiences, which are always occurring, they are also thought to be continually adjusting to optimize our understanding of the world around us and to allow prediction of future occurrences. In his TED Talk, The Riddle of Experience versus Memory, Kahneman (2010) discusses the idea of “the experiencing self’ in which he notes that we are always living in two different experiences: in the present and in the remembering past. He also adds that we think of our future as “anticipated memories.” What Kahneman means by this is that all of our perceptions, anticipations, and current experiences are constantly being informed by our past. On the same note, this means that as experiences occur and become past memories, our experiencing self is also changed.

The Issue of Ableism

Ableism is just one example of how this ability to generalize knowledge and project understanding onto the world around us has become maladjusted. As stated by Bermudez (2020), cultures decide which people are desirable and worth investing time and capital into, while others are labeled as disposable (p. 17). In our culture, perceptions of disability have been “produced and circulated through the eugenics model, the medical model, the charity model, and the social model of disability” all of which encourage the oppression and exclusion of disabled people as they all categorize disability as “undesirable, disposable, and in need of cure and pity” (p. 17).

Gappmayer (2020) defines ableism as “a network of beliefs, processes, and practices that produce a particular kind of self and body (the corporeal standard) that is projected as the perfect species-typical and therefore essential and fully human.” And further, defines “disablism” as “a set of conscious or unconscious assumptions and practices that foster the different or unequal treatment of people because of their actual or presumed disabilities.” Society expects people to be capable of walking, deciding what they want to do, and managing their own daily life; and when they are unable to do these in the expected way, we perceive them as being disabled. In terms of cognitive psychology, when people do not fit our schemas of what a “normal” person looks or acts like, we immediately categorize them as “other.” This, in conjunction with the medical model of disability, leads many to associate “other” with illness and the need to be cured or fixed. A New York Times article published in 2004 by Harmon, cites the feelings that a group of autistic people have about the medical model and the portrayal of disabilities such as their own being “in need” of a cure or behavioral corrections. One participant in the interview says, “We don’t have a disease…so we can’t be ‘cured.’ This is just the way we are.”

Even the social model, which opposes the medical model and argues that people are disabled by their environment rather than by their impairment, is limited in the way it “works towards inclusion within the existing social order rather than demanding wide-scale structural change” (Bermudez, 2020, p. 17). Though disability is a socially constructed categorization of human beings, the effects of historical and contemporary social oppression of this group are real and apparent. Systemic discrimination, which is rooted in history, continues to affect a significant amount of the oppression disabled people face (Friedman, 2018, p. 1). For instance, approximately 50% of diabled people experience poverty (p. 2). It is important to remember that although individuals also feel this exclusion on a personal level, the oppression is always socially, culturally, politically, and economically produced (Gappmayer, 2020). Perceptions inform infrastructure, institutional operations, and legislation which creates this multi-dimensional oppression experienced by othered groups.

These problematic models of disability are made widespread through media representation. Media is an integral part of culture and of the formation of ableist schemas, as media content strongly influences our view of the world. Though people with disabilities make up the largest minority group in the United States, many able-bodied people do not have people with disabilities within their social circle, or interact with them regularly. Thus, for a large part of the population, building a concept of disability is limited to the negative stereotypes that permeate our culture’s popular representations of those with ability differences. A common thread is that of the “inspirational disabled,” a seemingly benevolent narrative aimed at creating rosy sentiment surrounding those with differing physiological or cognitive abilities. As noted by Billy Golfus in “When Billy Broke his Head,” such inspiration stories are equally harmful, as they enforce the concept of disability as something to be overcome, combatted, or “cured,” again reflecting a problematic model (Campbell, 2008). Golfus went as far as to explicitly state, in the opening of his film: “this ain’t your average inspirational cripple story.”

Schemas associated with ableism are strong, often constructed via a lifetime of exposure to stereotypes, prejudiced comments, and idealized concepts of what human bodies and minds should look like. They are also not limited to the able-bodied; even Billy Golfus, who experienced the world from the perspective of a disabled person, noted biased schemas within his own thinking toward disability. Despite their ingrained nature, ableist schemas are not fixed. As pointed out by van Kesteren and Meeter (2020), optimal memory is actually quite pliable. We are built to adjust and integrate memories to serve our future needs. This can be both a subconscious process and an active process. Fiona Kumari Campbell (2008) delineates several active means of adjusting schemas. She proposes new ways of thinking about disability, questioning the existence of a true “norm,” stating that the perfect “able-bodied” human is more of a theoretical concept than a reality (Campbell, 2008). It is these kinds of shifts in perspective that will start to dismantle negative schemas surrounding people with physical, cognitive, or developmental differences. Gappmayer (2020) argues that the two main elements that contribute to ableism are the notion of the “normative individual” and the enforcement of a constitutional divide between “human” and “non-human” characteristics. Again, because these notions are socially constructed, this also means that everyday sayings, interactions, and discourses can create difference in both of these regards. However, what is socially constructed, can also be socially deconstructed.

Ableism and Cognitive Psychology

When discussing ableism in the medical field of psychology, it is crucial to remember that data and scientific results are not objective facts, but rather represent one of many possible truths (Gappmayer, 2020). Supposed “truths” such as disabilities being inherently negative or that all disabled people suffer from their disability, and thus are in need of curing or fixing, is not necessarily correct even if some research might imply so. For example, data might state that disabled people are more depressed than non-disabled people, however, this set of data can imply many different “truths” depending on how we conceptualize it. If our schema of disability, which has been informed by our culture and past learning about disabled people, encourages us to believe that disability equates to suffering, then we might infer that disabled individuals are more depressed because of their disability. But this is not necessarily the truth. Harmon’s (2004) NYT article includes a quote which says, “people don’t suffer from Asperger’s [or Autism]…they suffer because they’re depressed from being left out and beat up all the time.” This notion directly correlates with the social model which posits that negative effects that correlate with disability are socially, culturally, and institutionally caused rather than being caused by the disability itself.

It is true that our contemporary understanding, perceptions, and schemas about disability are not only misinformed, but also extremely harmful and oppressive. In our daily actions, we reinforce and reproduce these differences which isolate disabled people from the general population (Gappmayer, 2020 & Friedman, 2018). However, what we do have to our benefit, is the incredible ability of our brains to readily accept new information and adapt our worldview. The flexibility of our brain means that we soak up information from our surroundings and often internalize negative information, stereotypes, and harmful assumptions, but it also means that we can intentionally re-learn and create new understandings if we so choose to.

Memory is used to make everyday decisions, to learn, to accumulate an understanding of the world, and maybe most importantly, to self-improve and evolve (Wang, 2007). Though remembering is a private experience, we can also change our past memories with current actions, experiences, or conversations. Supported by van Kesteren and Meeter (2020) is the thought that the act of “retrieval,” or re-activating neural connections, alters the past memory again, in the present, by updating it with currently learned information. Then, it is reconsolidated into an existing, but updated, schema. This is how we are able to build off of past understandings and to incorporate new information constantly. Knowing that schemas are malleable and adaptive means that we can begin to specifically discuss how we can reshape our brains to incorporate a more disability-friendly outlook.

Discussion

As humans, we are capable of immense learning, understanding, critical thinking, and self-awareness. With that, it is important that we constantly monitor the input that our environment has on our schemas and understanding of the world. It is each of our own responsibilities to carefully select the media we consume, facilitate the associations we make from our environment, and continually educate ourselves and unlearn problematic information. By normalizing the difference that disability is, but actively refusing to associate disability with inherently negative traits, we can become more supportive and effective disability allies. According to the participants in the Ostrove et al. (2019) study, a good ally “must have self-awareness of their own positionality and able-bodied privilege…including not only a sense of how to use that privilege to effect social change but also an acknowledgement of the limited nature of their own knowledge and experience.” Furthermore, “dominant group members must be willing to share resources and power, give up their prejudices and a belief in their own superiority, and be flexible in relation to non-dominant others.” Like memory, unlearning is a continual, lifelong process.

Part 2: Kinds of Memory

Sorting and Mapping Environmental Input

The first of these mechanisms we will explore is working memory. In his 2013 Ted Talk, Peter Doolittle describes working memory as “the part of our consciousness that we are aware of at any given time of day.” Working memory is the information that occupies our focus in the present moment. It allows us to take in information, process it, and integrate it with our past experiences to strengthen our understanding of how the world works. A key aspect of the working memory system is that it has a limited capacity (Baddeley et al., 2020). We operate in an environment that is teeming with information, yet only some of this data makes its way into our focus. To preserve our limited energy resources, our working memory holds only about four units of information at a time (Doolittle, 2013). This limited system has profound effects on our processing of the world. Since we cannot take everything in, some information must take priority while much of it is discarded.

How then, do we determine what information to focus our limited working memory system on? Part of the answer lies in our ability to task-switch. A mechanism within working memory, known as the “Central Executive,” is described by Baddeley et al. (2020), as the central control station which determines where our conscious awareness is focused at any given moment. For example, Baddeley et al. (2020) describes our change of focus while driving a car, from conversation with a passenger to intent focus on driving, as part of this Central Executive function. The central executive operates both deliberately (i.e., consciously), and automatically (i.e., unconsciously). Some of our changes in attention are very intentional, while others are driven by rapid, automatic processing.

Our ability to unconsciously switch our focus, processing certain stimuli while ignoring others, is based on schematic knowledge that we develop through our life experiences. For example, we do not always have to think consciously about where we focus our gaze while driving; it comes automatically because we have had years of practice. This reliance on our schematic knowledge eases our cognitive load and allows us to balance more tasks. Unfortunately, schemas are also the cognitive source of our bias. In examining Ableism, many of the discriminatory behaviors toward people with disabilities arise not from conscious hatred, but from an automatic response based on an ableist schema. To deconstruct ableism then, we will also need to look at the process by which schemas are created.

Knowledge Building

Doolittle (2013), states in his Ted Talk “what we process, we learn.” In other words, any information we actively process in working memory will be more readily available for recall in the future. What Doolittle is describing was the encoding of information from the working memory system into long-term memory. The element of long term memory most significant to the discussion of Ableism is semantic memory, or all of our generalized, stored knowledge. As we process information in working memory, some of it is encoded and attached to webs of existing knowledge, or what we refer to as schemas (Van Kesteren & Meeter, 2020). These schemas give us general rules for how our environment works and how we should function within it.

The development of schemas occurs through what Van Kesteren and Meeter (2020) refer to as a hierarchical memory process. Events we encounter in our daily lives are initially recorded with episodic detail. For example, you might remember this morning’s breakfast as an “event” with a beginning, middle, and end; your memory likely still includes sensory experiences such as tastes and smells. Because our brains are built for efficiency, over time, many of these superficial details are lost, while important knowledge is retained. This happens through consolidation, a process by which important knowledge is extracted from episodic events and linked together to create general knowledge-webs.

The memory of each individual morning meal you have had throughout life is lost because it is unnecessary. However, you have likely consolidated the individual memories of breakfast throughout your life into one general “picture” or understanding of the cultural practice of “breakfast,”and are likely able to recognize certain foods and drinks as being generally associated with that meal. This is schematic knowledge at a rudimentary level. These generalizations of personal past experiences are also known in cognitive psychology as schemas. A “schema,” as proposed by Bartlett (as cited in Baddeley et al., 2020), is a concept used to better explain how our knowledge of the world is structured and influences the way in which new information is stored and subsequently recalled.

Efficiency and the Facilitation of Bias

Dr. Kleinknecht (2020) notes that memory is built for efficiency rather than accuracy. That is, our minds have a limited capacity and limited energy for storing information and it simply can not remember every moment of our lives in accurate, episodic detail. Efficiency allows our brains to “get the job done” and survive in our environments by being able to use generalized knowledge to make predictions, anticipate the future, and respond to situations appropriately. To do this, we transfer the details from our episodic (“declarative”) memory into semantic memory for storage which Baddeley et al. (2020) defines as “a system that is assumed to store accumulative knowledge of the world) (p. 14). In other words, our long-term, stored memory is made up mostly of summarized knowledge gathered from our past experiences.

Van Kesteren & Meeter (2020) also emphasizes that brains are optimized to store information and to quickly discard any irrelevant, non-repetitive details. According to both Van Kesteren & Meeter (2020) and Van Kesteren et al. (2012), new information which is congruent with prior knowledge will be stored to long-term memory first (aiding in the creation and/or maintenance of schemas) while incongruent information will be discarded first. Though this process of efficiency is an evolutionary advantage which allows us to better predict the environment around us, it also promotes the creation and maintenance of negative and or harmful stereotypes about certain groups or populations. Although we are capable of critical thinking, it is not an automatic response to repetitive environmental stimuli. Because we live in a culture that teaches and promotes ableist ideas and thought through everyday stimuli (advertising, movies, infrastructure, etc.), we learn to build our understanding of the world around these same thoughts whether we are conscious of it or not.

What’s more, “when a schema becomes too strong, it can erroneously (mistakenly) associate new experiences” which facilitates the formation of false memories and misconceptions as well as become more likely to disregard memories which “don’t fit” with the existing schema (Van Kesteren & Meeter, 2020). That is, when schemas become ingrained into us at a massive cultural-level, not only do they become resistant to change, but they also become more expansive and more likely to continue to accept new information into said schema to support the idea whether or not it realistically does.

Deconstructing Bias

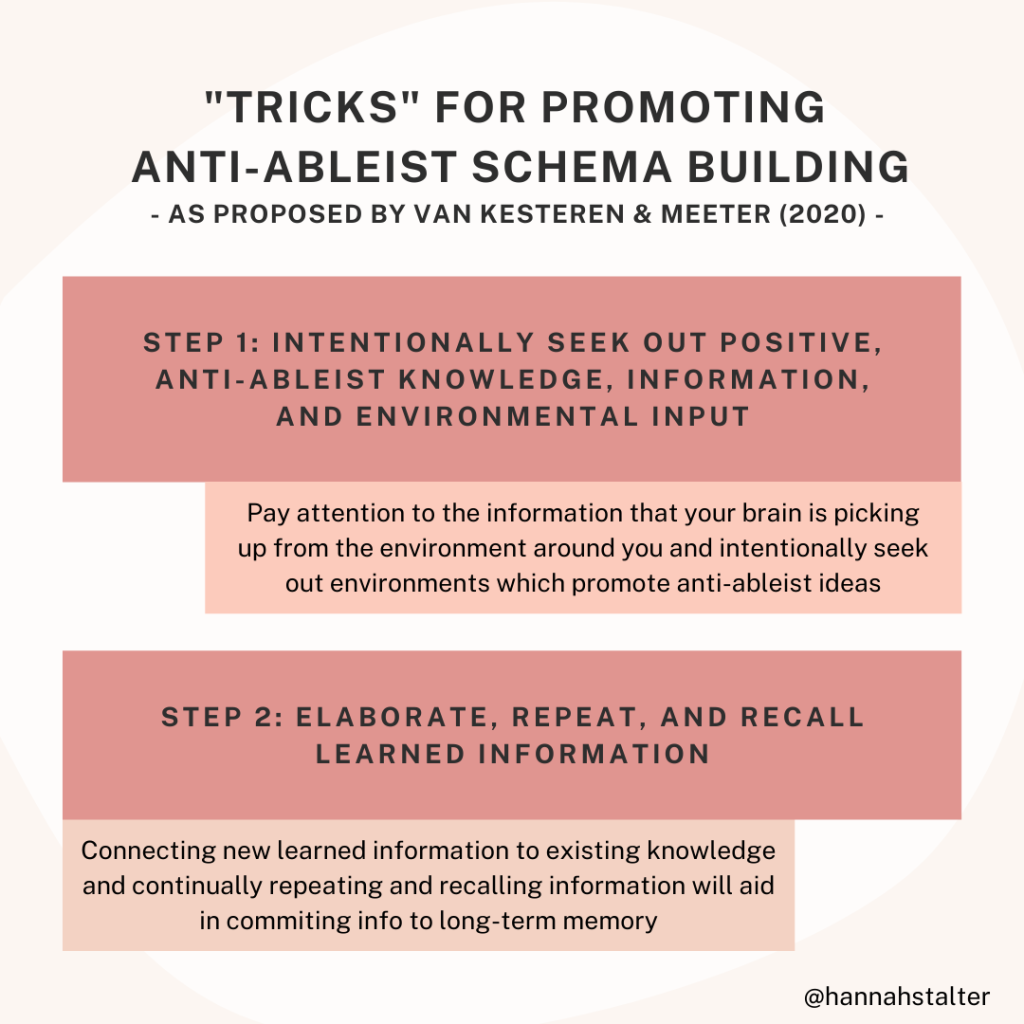

While we might not always be able to control our environment to the point of preventing our minds from taking in ableist notions, there are several ways to prevent and also un-do negative schemas and assumptions that we have built up over a lifetime. Van Kesteren & Meeter (2020) offers many specific ways to manage our memory and facilitate the long-term retention of specific detailed information which can act as a pathway to re-learn our assumptions about disablism and disabled people.

The first step in the process of memory storage is the encoding of environmental stimuli. Some “tricks” offered by Van Kesteren & Meeter (2020) to promote the long-term remembering of detailed information include elaborating on the information (connecting it to existing knowledge or asking yourself questions about it), reactivation of previous memories (integrating information with existing schemas), and making the memory distinct from others (creates less interfering neural pathways to promote easier retrieval of information). An example of each of these in terms of deconstructing our ableist thoughts might include having a conversation with someone about topics of ableism or disablism (elaboration), connecting issues of ableism to past, similar, personal experiences (reactivation of previous memories), or seeking out several mediums of information about ableism such as looking at infographics, reading books, and watching movies about disabled people (distinctiveness).

The second process of memory storage is consolidation (i.e, generalizing memories and creating schemas). This step is arguably the most important for committing new, socially aware, and culturally informed understandings of disabled people to long-term memory and fully unlearning and replacing ableist thoughts. The primary way to do this, as noted by Van Kesteren & Meeter (2020), is through repetition and spacing. As mentioned previously throughout this paper, past experiences are the foundation of our understanding and the more an experience occurs, the more prevalent and ingrained that understanding becomes. Thus, the more an individual intentionally focuses on either unlearning ableist thought and/or intentionally creating positive and informed experiences with disabled people and the more commonly and long-term this occurs, the more that understanding will become the primarily accessed knowledge. In the end, this will result in fewer accidental and unconscious ableist thoughts and actions.

The third and final step to long-term memory creation is the retrieval of information. Information which goes unaccessed in the brain is discarded in the name of efficiency. To prevent this, the more an individual is able to continually access a particular memory and schema, the more likely it will be to maintain storage in the brain. Van Kesteren & Meeter (2020) says that this can be achieved through episodic specificity induction (recalling previously learned information in high episodic detail). This can be done through storytelling, drawing, creating mental imagery, or re-watching movies or shows which trigger the desired memory.

Discussion

Schemas are the foundation of our understanding of the world around us. Unfortunately, schemas are built from our environmental stimuli which we can not always control; especially when understandings or assumptions are culturally pervasive and manifest in subtle and unconscious ways to many of us. And yet, even these unconscious assumptions influence our thoughts, behaviors, and actions which can be harmful to some groups and populations such as the disabled community in the United States. Ableism is a culturally pervasive set of assumptions which can be seen in virtually every area of society. Fortunately, cognitive psychology offers an explanation and solutions for unlearning disabled bias and implementing culturally and socially competent understanding instead. By manipulating our experiences and environmental input and by intentionally learning and remembering positive and anti-ableist information, we can deconstruct our harmful thoughts and create a more positive, supportive, and inclusive culture.

Part 3: Controlling our Memory, Schemas, and Mind

In our examination of ableism, we have discussed the formation of ableist beliefs from a biological perspective as well as the integration of ableist concepts within our schematic knowledge. To further understand and combat ableism, we must also acknowledge the degree to which discriminatory beliefs have roots in our histories and self-concepts. Self-concepts are formed through our interpretation of our own experiences within the context of our cultural and social beliefs. As Kleinknecht (2020) states, our memories of past experiences are precious; they connect us to one another socially, contribute to our identity, and inform our future actions. Autobiographical memory is also highly fallible, rendering it vulnerable to adjustment each time we access it. In this section, we will explore the ways in which autobiographical memory is involved in the formation and enforcing of ableism, and how the flexibility of our self-concept might be used in our fight against such harmful bias.

Autobiographical Memory

Autobiographical memory can be thought of as a system of organization for episodic memory. It is essentially a grand “schema of self.” As we encode episodic elements via the firing of specific neural networks, these become attached to frames (i.e., contexts) through consolidation, creating our larger episodic memory (Baddeley et al., 2020). By habitually accessing and building on certain episodic frames, we establish a “life story” which becomes our autobiographical memory. The narrative form of autobiographical memory is dictated by our cultural context, our language, and the social expectations we operate within. It is reinforced via repeated accessing. Each time we revisit the timeline of our experiences, we enforce certain themes, which form our beliefs about the self (Baddeley et al., 2020).

According to Conway (2001), the function of autobiographical memory is to “ground the self.” Conway suggests that Autobiographical memory applies order and hierarchy to episodic memories, creating a larger frame of reference in which episodic memories can integrate. Conway argues that autobiographical memory is a goal-oriented system which privileges congruence in self-concept. In other words, the present self is directed via autobiographical memory to focus on certain goals that match with the existing, developing narrative (Conway, 2001). If we look at our self concept in terms of narrative, autobiographical memory forms the plot. Kleinchnecht (2020), echoes Conway in her lectures, stating that the purpose of memory is for the future. Autobiographical memory, while seemingly oriented toward the past, is really what guides us in much of our decision making. The organization of episodic memory into a coherent self-narrative allows us to behave in a goal-oriented manner, using episodic memories to mark our progress (e.g., past successes, failures) and continue making steps toward achieving goals.

Memory Across the Lifespan and Our Sense of Self

The formation of autobiographical memory is influenced by both developmental growth (i.e., childhood, adolescence, adulthood), and cultural context. From a developmental perspective, the most important years for autobiographical memory and the development of self-concept seem to be in late adolescence and early adulthood, when many important “firsts” take place, such as graduating college, falling in love, or starting a first job (Baddeley et al., 2020). Early childhood memories tend to be fewer, and often exist without the context of an episodic frame. The reason for this has to do in part with the role of schemas and semantic knowledge in the consolidation of new memories. Van Kesteren et al. (2012) suggest that schemas, or existing networks of neuronal connections, make the processing of new knowledge more efficient. Schemas direct attention and encoding toward relevant information, and offer context for new memories. In early childhood, semantic knowledge is only beginning to develop, thus, fewer schemas are available to assist in the encoding of whole episodic memories. Another factor is the development of language, which is key to memory processing (Baddeley et al., 2020). In later childhood and into adulthood, once some schematic knowledge has been established, and culture, language, and social norms have been ingrained, episodic memories with greater longevity can form. It is these longer-lasting memories, formed during key developmental years in early adulthood, that have a great effect on self-concept and identity development.

Cultural context also plays a key role in determining what episodes become integrated into autobiographical memory and self-concept. Social beliefs, language, and interpersonal norms all influence what memories are retained. For example, there are significant differences in the content of autobiographical memories between East Asian cultures and American culture. In interactions with their children, American parents tend to encourage conversations about personal feelings, and reminisce on past events in terms of what was thought or felt during a given moment (Ross & Wang, 2010). In contrast, Asian parents are more likely to engage children in conversation about how to behave socially and function well within a group such as the family. These differing types of socialization lead to different focuses within autobiographical recall, and consequently, to different ways of identifying the self. People within western cultures tend to look back on singular events and discuss how they influenced them individually, whereas people from East Asian cultures tend to remember group interactions and relational changes as much more important. As Ross and Wang (2010) state: “autobiographical memory is categorically cultural.”

Memory Accuracy and Malleability

Cultural influences on memory have a direct impact on our schema building which then, in turn, have a direct impact on our society and culture. Regardless of the specific nuances of one’s culture, it will have an explicit impact on an individual’s values, beliefs, memory, and their behavior and daily decision making (Ross and Wang, 2010). To be socialized in a culture that “others” disabled bodies and creates systemic, institutional and social barriers against them, it is only expected that these notions carry over into individual perceptions. On a positive note, memories are also extremely malleable and are subject to change throughout the entire lifespan. Conway & Loveday (2015) refer to memories as “transient constructions” that contain many true, but also many inferred, details. The main function of this ability to make inferences, assumptions, and generalizations is to maintain a coherent, confident, and positive self as well as to summarize learned knowledge (so as not to overwhelm the self with too much information). Memories are intended to be inaccurate for an evolutionary purpose, but as noted, this can cause social problems in our societies.

In Schacter’s (1999) extensive exploration of the “seven sins of memory,” various by-products of a malleable and inaccurate memory system are laid out and examined. In this paper, Schacter notes various methods which might influence one’s belief system, either for better or worse, such as: misattribution, suggestibility, bias, and persistence of existing beliefs. These are all examples of how our memories and schemas are influenced by our particular memory system and can act as possible explanations for the root of ableist thinking and beliefs. The first of these, misattribution, is the act of misattributing a piece of information from one place or event, and remembering it from another source. An example of how this might promote biased thinking is through the misattribution of false or misleading information. For instance, one might read a negative, pseudo-scientific “fact” about disabled people on a facebook post, but might instead incorrectly remember it as being from a peer reviewed, academic paper instead. In this case, the individual would be assuming these falsehoods to be fact as a result of misattribution.

The second “sin” of memory mentioned above is suggestibility; the spontaneous occurrence of a false memory when a current situation is conceptually or perceptually similar to a previous one (Schacter, 1999). Another example of this would be through the suggestibility-effects of priming. According to Baddeley et al. (2020), the priming effect (perhaps through the use of leading questions or emotionally charged language) can directly influence a person’s memory of an episodic event. Suggestion can influence memory in several different ways and the language we use to discuss disability can often prime individuals to think negatively about it. When it is suggested by our culture and society that disabiled people are in any way lesser because of their disability, our memory might be unknowingly reattributing or reinforcing negative ideas about disabled people.

Suggestibility then directly influences biased thinking and the persistence of these beliefs. Bias, as defined by Schacter (1999), is the notion that “encoding and retrieval are highly dependent on, and influenced by, preexisting knowledge and beliefs.” Once more, the influence of our culture’s beliefs and values have a direct, and lasting impact on, our own thinking and perceptions of events. Schemas and memory favor “sameness” and will make stronger connections with pre-existing knowledge. That is, our memory is naturally more likely to reinforce existing schemas than it is to create new ones; especially if it is contradictory to what we already believe to be true. Despite efforts to forget knowledge or beliefs, this fallback on existing schemas also reinforces the continual persistence of existing thoughts. As much as one might want to forget or unlearn, that will likely always be easier than creating brand new schemas. However, this does not mean that it is impossible. Schacter also points out that despite these often undesired by-products of having a malleable and influential memory system, it’s important to remember that these are not necessarily flaws in a system, but rather exist because they are in fact evolutionary advantages. That being said, the malleability of our memory and minds also creates opportunity for change and re-learning.

Discussion: Using Cognitive Psychology to Become Anti-Ableist

As discussed, our brains are built for optimization rather than accuracy. That is, we are quick to generalize and summarize new information, but also to quickly discard any irrelevant details. Using our understanding of memory as a suggestible, adaptive, and ever-changing occurrence, we can learn how to best unlearn our ableism and replace our old, pre-existing schemas with new, positive and socially conscious ones. Using cognitive psychology, we can not only become equitable thinkers, but also actively anti-biased and anti-ableist beings.

First, we must attempt to unlearn the negative and harmful assumptions we have, such as with the medical model, which surrounds and deeply stigmatizes disability. Recognizing that disability is merely a socially constructed difference, and not a category that should be used to isolate an entire population, is the first step to normalizing disabled people and preventing harm or reinforcing suffering. As noted in Harmon’s (2004) article, many of the behaviors we try to fix or correct in disabled people are only to ease our own discomfort and not because of any true need for that behavior to require change. In the case of Autism, “some autistic tics, like repetitive rocking and violent outbursts…could be modulated more easily if an effort were made to understand their underlying message, rather than trying to train them away” (as cited in Harmon, 2004). Other traits, such as difficulty with eye contact, understanding humor, or unease with breaking from routine, might not require such huge corrective efforts if others were simply more tolerant of these abnormal behaviors. In this instance, difference is difference and nothing more. Not making eye contact only becomes harmful when we begin to punish those who are unable to do it. Otherwise, it is a completely benign behavior. An example of a difference which exists completely stigma-free in our modern society is left-handedness. Though it might make some activities more difficult (like using a pair of scissors), our society has easily made accommodations (left-handed scissors) and have completely normalized the existence of left-handed people. We acknowledge the difference, but do not act or treat left-handed people any differently. This, as Gappmayer (2020) argues, is exactly how we should go about reconceptualizing disability. Simply, “different;” but nothing more than that. In essence, if we simply refuse to act differently around disabled people, or “refrain from doing,” we will eventually de-stigmatize disability. But to do this, we must unlearn all associated stigma.

The social model argues that we should change society and institutions, such as by adding tools like left-handed scissors, in order to create and establish equality. Theoretically, positive attitudes towards disabled people will occur automatically alongside the removal of difference. While this might be good in theory, and definitely still necessary in many cases, it cannot be our only form of change. The issue with this is that it would require accommodations for every single disabled trait, and additionally, that some accommodations might conflict with other disabled traits (Lim, 2017). For example, adding railings to every sidewalk might benefit the visually impaired, but it would become an obstacle for wheelchair users. Unfortunately, this is an unrealistic method to equality.

So how can we, as individuals and as a society, dismantle ableism? Friedman (2018) says that, “the most prominent intervention is the common in-group identity model, which in recognizing the role of social categorization, uses the positive consequences of in-group membership and recategorization instead of trying to reduce the negatives of outgroup membership” (p. 14). Similar to Gappmayer’s (2020) perspective, we ought to unlearn disability as “othered” and reconceptualize it as a simple difference and variation of human bodies. Friedman (2019) also cites that, in a study conducted of non-disabled people’s perceptions of disabled people, aversive ableism is the most common form of discimination in our culture. And because this is an implicit and internalized form of discimination, it is also the most difficult to correct as it involves the individual unlearning of false generalizations and negative perceptions. In order to do this, we must understand the psychology of memories and learning.

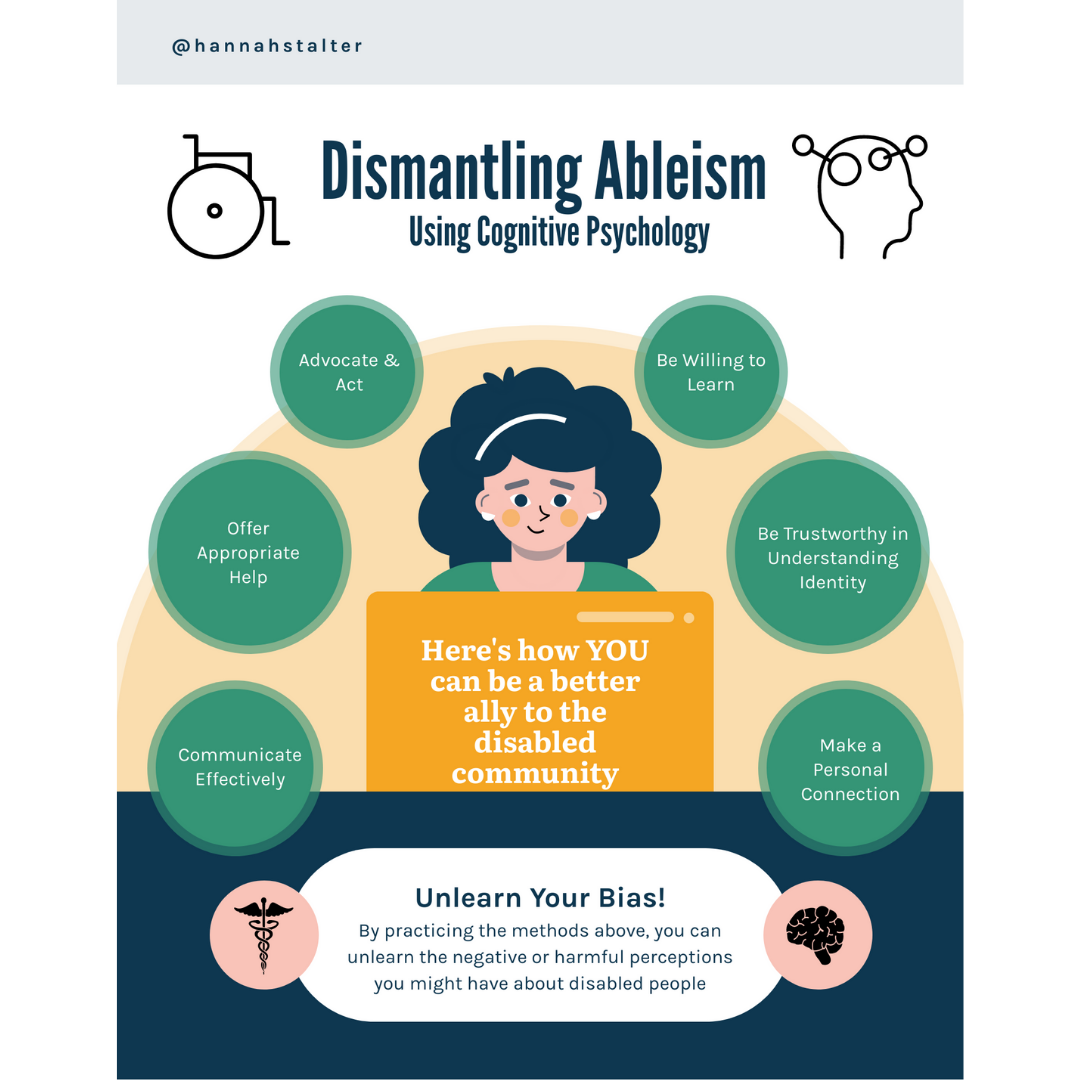

In this paper, we have already established that the learning process happens through experience, and whatsmore, that our perceptions and understanding can change and evolve along with new experiences. That being said, the most optimal way to reconceptualize disability is to destigmatize it in our own daily lives. Or, as Gappmayer says, refrain from treating disabled people differently. This approach is also directly supported by the disabled community. A study by Ostrove, Kornfeld, & Ibrahim (2019) interviewed disabled people and asked what a good disabiled-ally looks like. According to their study, disabled people do not want to be treated in a condescending way, pitied, or ignored. Simply put, they wanted to be treated the same as non-disabled people. Ostrove et al. (2019) also cited six common themes noted by their disabled participants such as: offering help when appropriate (and asking if help is wanted), being trustworthy in understanding identity (understanding that while disability is an important identity; disabled people are multidimensional and more than their disability), taking political action on behalf of the disabled community, being comfortable around disabled people and making intimate, personal connections with them, and being willing to learn.

In conjunction with this data and with the understanding of memory, we argue that the best ways to become a better, more informed, disability-ally are to incorporate disabled people in your life as frequently as possible and to be constantly examining and re-examining your personal beliefs and where your information and suggestibility is coming from. Whether it be making personal connections with disabled people, consuming media with healthy and positive representations of diabled people, or listening to and educating yourself on disabled discourse and voices, the best we can do is continually, and intentionally, unlearn negative associations by replacing them with positive and supportive ones. Eventually, our internalized ableism will dissipate and disabilities will be collectively normalized.

Conclusion: Practical Steps to Becoming Anti-Ableist

Several ideas about memory, mind, and their connection to the social issue of ableism have been discussed throughout this paper. As has been noted, the primary functions of memory encoding, storage, and retrieval are evolutionary in nature and have adapted for optimal storage, to inform behavior, create and maintain a sense of self, and for the ability to make predictions and to translate knowledge from one event to another. Without these innate abilities, our memory would simply be a collection of events and details with little semantic understanding, critical thinking, and would serve no purpose or function to us. Our human ability to create schematic understanding and to use our past to make assumptions about our future is a unique and important one. Though there are negative by-products when these abilities are in the context of a biased culture or society, the flexibility of our mind also leaves space for change. In the case of ableism, we understand that it is difficult to escape the influences of thought from our environment. To begin the difficult task of change, set some simple goals. As with any large undertaking, small, consistent steps are most effective. In her lectures, Kleinchnecht (2020) references an “action continuum,” on which differing levels of allyship are explored. Along the continuum, the first step toward allyship is education. Find books or articles on ability differences, and set a small reading goal. If you feel ready to take another step, consider talking with others about your learning journey. Engaging in these conversations will strengthen the anti-ableist schemas you are cultivating in your own cognition. As you develop in your allyship, you may find and support groups who actively speak against ableism. You may eventually feel equipped to address issues of injustice when you encounter them. No matter where you are in your process of becoming an ally, each step you take is important, necessary, and valuable. Through our daily actions, intentional examination of beliefs, and replacement of old schemas with new, we can become better allies to the disabled population and live an anti-ableist life.

Project Take-Aways

- A better understanding of how to apply our knowledge of psychology to social issues and change

- An understanding of the root causes of biased thought

- A deeper understanding of our personal thoughts and schemas

- Knowing our flexibility and ability to change

References

Baddeley, A., Eysenck, M. W., & Anderson, M. C. (2020) Memory, 3rd edition. Psychology Press, Routledge. New York, NY.

Bermudez, A. (2020). Deconstructing/reconstructing cultures of undesirability: A critical review of #DisabledPeopleAreHot and social media activism. Journal Production Services. University of Toronto. Retrieved September 28, 2020 from https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/

Campbell, F. A. K. (2008). Exploring internalized ableism using critical race theory. Disability and Society, 23(2), 151-162.

Campbell, F. K. (2008). Refusing able (ness): A preliminary conversation about ableism. M/C Journal: A Journal of Media and Culture, 11(3).

Conway, M. A. (2001). Sensory–perceptual episodic memory and its context: Autobiographical memory. Philosophical Transactions. Biological Sciences, 356(1413), 1375–1384. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2001.0940

Conway, M. A. & Loveday, C. (2015). Remembering, imagining, false memories & personal meanings. Consciousness and Cognition, 33, 574-581. DOI: 10.1016/j.concog.2014.12.002

Friedman, C. (2018). Aversive ableism: Modern prejudice towards disabled people. Review of Disability Studies, 14(4). Retrieved September 28, 2020 from https://rdsjournal.org/index.php/journal/article/view/811

Friedman, C. (2019). Mapping ableism: A two-dimensional model of explicit and implicit disability attitudes. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies. Retrieved September 28, 2020 from https://cjds.uwaterloo.ca/index.php/cjds/article/view/509

Gappmayer, G. (2020). Disentangling disablism and ableism: The social norm of being able and its influence on social interactions with people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Occupational Science. DOI: 10.1080/14427591.2020.1814394

Golfus, B. & Simpson, D. (1995) When Billy broke his head… and other tales of wonder.

Harmon, A. (2004, December 20). How about not ‘curing’ us, some autistics are pleading. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/20/health/how-about-not-curing-us-some-autistics-are-pleading.html

Kahneman, D. (2010). The riddle of experience versus memory. [Video]. TED. [insert link]

Kleinknecht, E. (2020). PSY 314: Memory and mind class lectures. [PowerPoint Slides]. Pacific University Moodle.

Lim, C. M. (2017). Reviewing resistances to reconceptualizing disability. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 117(3), 321-331. DOI: 10.1093/arisoc/aox007.

Ostrove, J. M., Kornfeld, M., & Ibrahim, M. (2019). Actors against ableism? Qualities of nondisabled allies from the perspective of people with physical disabilities. Journal of Social Issues, 75(3), 924-942. DOI: 10.1111/josi.12346

Ross, M., & Wang, Q. (2010). Why we remember and what we remember: Culture and autobiographical memory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(4), 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610375555

Schacter, D. L. (1999). The seven sins of memory: Insights from psychology and cognitive neuroscience. American Psychological Association, 54(3), 182-203.

Van Kesteren, M. T. O., Ruiter, D. J., Fernandex, G., & Henson, R. N. (2012). How schema and novelty augment memory formation. Trends in Neuroscience, 35. DOI: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.02.001.

Van Kesteren, M. T. R., Brown, T. I., & Wagner, A. D. (2016). Interactions between memory and new learning: Insights from fMRI mulivoxel pattern analysis. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 10, DOI: 10.3389.fnsys.2016.00046

Van Kesteren, M. T. R. & Meeter, M. (2020). How to optimize knowledge construction in the brain. NPJ Science of Learning, 5. DOI: 10.1038/s41539-020-0064-y.

Wang, Q. & Ross, M. (2007). Culture and Memory. In The Handbook of Cultural Psychology. S. Kitayama and D. Cohen, eds. The Guildford Press, New York & London.