2

Carli Feist; Brittany Krechter; and Nina Nova

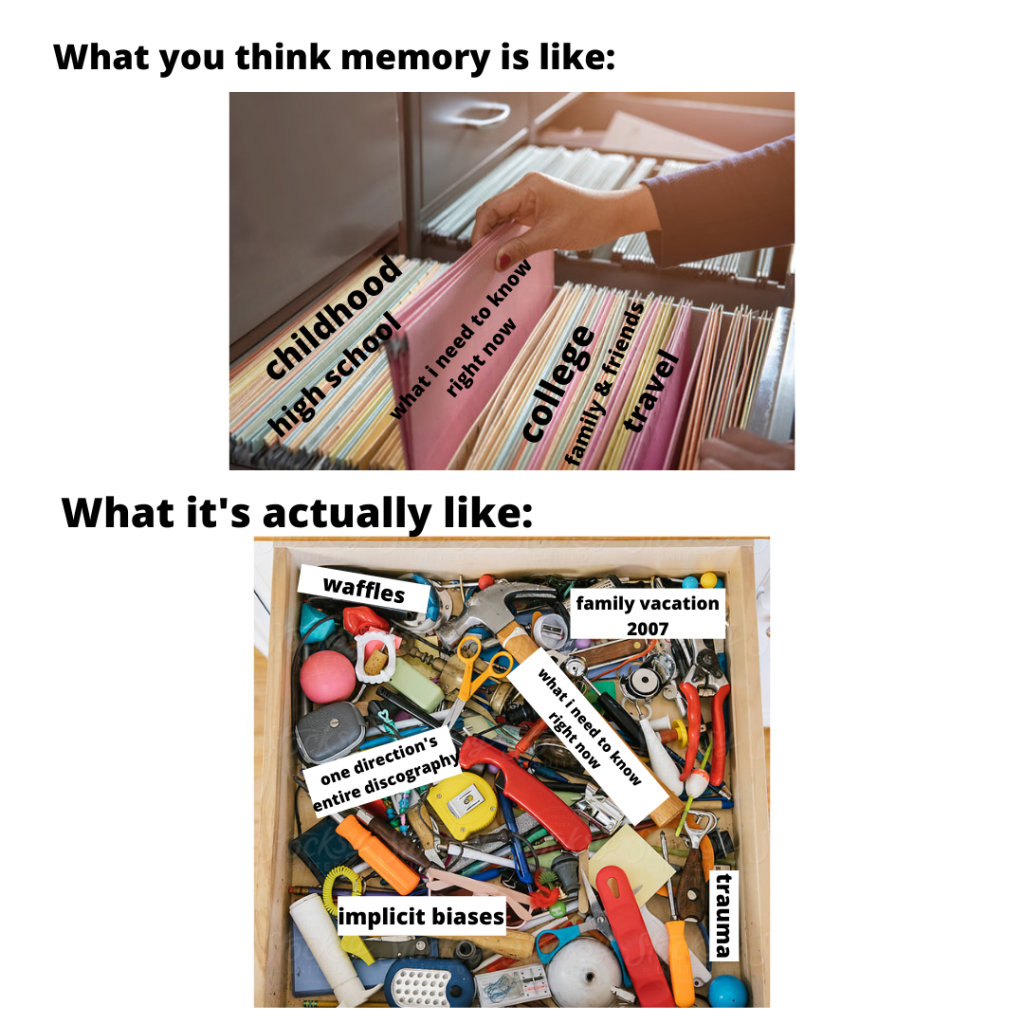

The working systems of our minds are often compared to computers with regard to the ability to encode, store, and retrieve memories readily. Although there are some aspects of the mind that may be similar to the way computers function, these processes pertaining to memory are completely unique to the human mind and do not relate to the features of a computer. This idea plays a massive role in our ability to forget, which, as William James stated, is just as important as remembering (Week 4 Lecture). If our minds were in fact like a computer, it would be much more difficult to forget, and, although most people view forgetting as a negative aspect of the mind, it is one of the essential ways in which we are able to learn new habits and behaviors. Now more than ever, it is crucial that we put our imperfect minds to work in an attempt to eliminate social issues such as racism. Racism and oppression have been prevalent in the United States for over 400 years, and although people argue that things have improved, the fact that these issues still exist show that there has not been drastic enough change. The reason for this has to do with people being content with being “non-racist.” However, the most important part of eliminating racism is becoming “anti-racist.” In order to do so, we must use what we know about the mind to learn new behaviors in actively speaking out against racism. Knowing what memory is and how it works, appreciating that memories formed in the brain are indeed changeable, and understanding the difference and balance between universal and cultural relativities of the mind are principal notions in the process of eradicating racism.

The overall function of the memory system is to help humans survive and thrive in their environments, which includes the ability to adapt. This ability to adapt is essential in the fight against racism in an attempt to unlearn racist habits and beliefs and relearn what it means to be accepting of all human beings. Baddeley et al. explain, “We are good at remembering patterns of repeating events, a skill that helps us understand the world using this understanding to strip away redundant information and using the core meaning for future planning” (2020). This process makes our minds extremely flexible and gives us the ability to access a certain event from the past to use when it is appropriate in the future. The preconceived notion that once a memory is formed in the brain it does not have the ability to change is false. Memories formed do have the ability to change, and just because they have been “stored” does not mean that they are permanent. The malleability of our minds is what gives humans the ability to unbind themselves from their initial biases, hold a capacity of awareness of these biases and their dangers, and take action to adjust thought patterns and respond in a less biased fashion in the future.

Starting at the cellular level, memories are simply surges of electrochemical signals firing from neuron to neuron in the brain. These action potentials increase their likelihood of firing again with each occurrence; strengthening neural connections and creating more efficient ways of getting to the same end result (Baddeley et al., 2020). This end result could take the form of recollection of past experiences, the connection of old knowledge to new, or some combination of the two. These neural networks that do the hard work of encoding, the translation of environmental information into meaningful memories, exist within a greater system of interconnected parts. The different lobes of the brain and their specific structures all make up the individual pieces necessary for the overall functionality of the cognitive system, which allows us to make and store memories. The most important brain areas involved in memory are the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex (Baddeley et al., 2020). While they do slightly different things, the hippocampus deals primarily with long-term memory consolidation and the prefrontal cortex help retrieve those memories, they work together to give us a feeling of knowing and an understanding of our past experiences (Baddeley et al., 2020). These structures, combined with the functioning of the rest of the cortex, are what make up the cognitive system that allows us to remember what we know and learn new information.

Biologically, the memory system works very similarly in all human beings; however, cultural relativities make an immense impact as to what individuals do with these memories and how they are perceived within their respective environments. Neurologically, information processing and memory formation are universal. The anatomy of the brain from person to person is the same, with the same location of lobes, cortexes, etc., and each brain requires energy to function. The process of retrieving episodic memories involves “the reinstatement or reconstruction of information encoded in memory” (van Kesteren, Brown, & Wagner, 2016). It is the selection of what and what not to “keep” in our cell assemblies where cultural relativities are a great influence. Different cultural values can create a lens through which environmental stimuli are taken in. For example, western cultures place significant importance on the concept of individualism. Because of this, when prompted to recall autobiographical memories, members of this society are more likely to describe personal lived experiences that center on the self (Wang & Ross, 2007). This is contrasted by the function of memory for members of eastern and Asian cultures, who shy away from self-centeredness in favor of family connections and social expectations (Wang & Ross, 2007). These examples point to the idea that, despite all humans having the anatomical structures required for it, memory is not always universal.

In the same way that culture and environment shape our memories, the way that we experience events can influence in what context we remember them. In his TED talk, Daniel Kahneman describes the relationship between the experiencing self and the remembering self. The experiencing self operates in the moment and quickly takes in information from the environment without giving much attention to analyzing or evaluating the memory that is being created (Daniel Kahneman, 2010). The remembering self decides how you feel about the memories that have been created and subsequently makes decisions in the present based on them (Daniel Kahneman, 2010). These two “selves” have a lot to do with how our memory can, in some ways, be fallible. Kahneman describes a situation in which someone listens to a beautiful piece of music that they truly enjoy, but at the end of the music a loud screeching noise is heard and the listener now believes that the experience has been ruined. This is because they are operating from the perspective of the remembering self, which ignores the entire portion of the experience that was good. From this example, we can see that not all memories occurred exactly in the way our experiencing self went through them. Our memories get skewed through the perspective of our remembering self. This is important information to be aware of when thinking critically about our past experiences. Oftentimes, we create negative memories based on one defining moment instead of looking at the entire experience objectively.

This preconceived notion that once a memory is formed in the brain it does not have the ability to change is false. Memories formed do have the ability to change, and just because they have been “stored” does not mean that they are permanent. The goal to overcome false beliefs and misconceptions is to “create robust schemas that are . . . strong enough to help to remember and predict, but also malleable enough to avoid such undesirable side effects” (van Kesteren & Meeter, 2020). This is an idea from the article “How to optimize knowledge construction in the brain” that is essential in the process of becoming an anti-racist. With this in mind, we can consider ways in which ideas of racism or prejudice can work its way into someone’s scope of knowledge. An individual who has lived through hardship and oppression, especially an individual of color, would likely have completely different ideas and beliefs regarding the issues of racism. Someone who has lived their lives unaffected by the color of their own skin wouldn’t have developed the breadth of schemas related to racism compared to someone who has.

While there are people who express genuine hatred, many people who have yet to embrace the mindset of being “anti-racist” are simply acting upon their underdeveloped schemas and implicit biases. The frames and schemas we develop throughout our lives and during childhood often provide an integral framework for our behavior and belief systems as adults, but that doesn’t mean we are stuck with them. While it can be difficult to recognize when our ideas don’t align with our morality, and increasingly more so to alter them, it is nevertheless important to expand our understanding of others and their experiences. Learning habits of self-reflection and exercising empathy in all situations are great ways to start the process of being anti-racist. When considering the metacognitive self-regulation cycle, it is useful to engage in forethought or planning, performance, and reflection. In this context, forethought can be attributed to identifying your own morals or questions you have about racism and bias. Performance is the subsequent action you take on those morals and the conversations you have to get those questions answered. Reflection is then the process of thinking about what else there is to learn, what positive or negative aspects did you encounter in those conversations, and how you can alter your thoughts and behaviors in the future. This cognitive process is extremely helpful in adopting the anti-racist mindset.

There is so much that has yet to be discovered about the mind and memory systems. What we do know about its flow of information across the cortexes is the ability to adapt and change when exposed to new situations. Knowing what it takes to form new habits and behaviors, we can truly reflect on any racist beliefs we previously held, either explicit or implicit, and work passionately to form new behaviors toward racism to become anti-racist. If we do not continue to challenge our minds to get rid of these behaviors and substitute them with ways to become anti-racist, these biases will still exist in our minds and be available for retrieval at any given time. Ibram X. Kendi explains, “But there is no neutrality in the racism struggle. . . One either allows racial inequalities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an antiracist. The claim of ‘not racist’ neutrality is a mask for racism” (2019). Kendi is exactly right, and this holds true for what happens neurologically as well. If we do not continually speak out against racism and challenge any underlying racist beliefs we might have, then these behaviors will not change and there will not be opportunities for new cell assemblies to form and be repeated to create schemas. With the human mind being as complex as it is, it is vital to understand how it works, the adaptability of the mind, and the aspects of the mind that are universal and those that are cultural, and use this knowledge to actively encourage, inform, and show others what it means to be anti-racist.

The Structure of Human Memory and its Impact on Racial Bias

The human memory system is one of particular strengths and abilities. It manages to sort through and assign meaning to every encounter, thought, and stimulus of our daily lives, all the while allowing for purposeful social interaction and necessary problem-solving. This unique capability of the human cognitive system is reflective of its need for efficiency and functionality. As the field of cognitive psychology progresses, we are constantly learning new ways that our minds internalize and manipulate information, and what the best practices are for maximizing our learning. Additionally, modern research has shed light on sociocultural issues of race and bias, which had previously been omitted from much of cognitive psychology discourse. Bias, just like all internalized representations of our world, is inevitable. Lived experiences and cultural context are contributing factors to the formation of biases, and concepts of cognitive psychology offer strategies for addressing bias to better reflect our morality and desires for the future of not only ourselves but the rest of society. These strategies cannot be understood, however, without knowing the context of our memory systems and how they work to create internal copies of our external world.

In order for our minds to perform and take on the sheer volume of the environmental input that we receive, humans must be able to store information and manipulate that information in a way that benefits the memory. The reason why this does not always work is that there are huge limitations when it comes to how much we can actually store and manipulate. This is known as cognitive capacity. Cognitive capacity is the balance between holding information in the mind and being able to manipulate that information to form ways of remembering and knowing. Although humans possess a limited amount of space and energy to do this, there are key functional ways to work around these limits. There are certain ways that individuals can improve their memory span, but in order to do so, one must know where the points of improvement are. Once this is determined, we are able to create exercises that potentially have a meaningful transfer to the mind. Peter Doolittle’s main point in his TED Talk on working memory was based on this idea. He described that our ability to leverage the working space that we have matters more than the actual memory span we hold. Once we know how to leverage this working space, we can attempt to consciously manipulate and fix any biases held within the mind.

Giving the mind different ways to store and manipulate the information provided to us by the environment will be advantageous to an individual’s cognitive capacity, and learning science gives us the tools to do so. Because there is a conscious effort involved in implementing the different strategies of learning science, we can use this same idea in working to eliminate everyday biases. Effort and repetition are required for effective learning to take place, and this will be crucial in the process of noticing one’s biases toward a targeted or minority group and being able to consciously form new ways of thinking. Once we are able to create a new and specialized schema that excludes the specific bias that originally held its own space in the mind, we must use strategies to increase the likelihood that these less-biased patterns of thinking will continue to be retrieved. Since we cannot manually go into our mind and pick out the thoughts that shouldn’t belong there, we have to rewrite our thoughts, and then use the strategies from learning science, such as retrieval practice, spaced practice, and dual coding to make sure these newly stored and manipulated thoughts are the ones that will be at the forefront of our minds.

There are different types of processes that play a role in how we represent our experiences and build on our knowledge and expectations. Additionally, these processes can contribute to the formation of biases in our minds, as our cognitive system is not always accurate. Two of these processes include episodic and semantic memory. Episodic memory allows us to have a feeling of reliving. It refers to our capacity to recollect specific events and use this information retained for what is called “mental time travel” (Baddeley et al., 2020). The process of forming episodic memories is reliant on the capacity to encode and then retrieve these specific events, and in order to do so in an effective manner, it is important that the material be meaningful and well-organized (Baddeley et al., 2020). Endel Tulving explains that increasing the ability to access these specific types of information will enable conscious shifts in our awareness of what we have done and what we know, which will play a role in what humans must do in order to notice, think about, and fix racial biases. Episodic memory can be thought of as a system, with specific pieces of episodic memories being episodic elements, that exist within a conceptual frame (Conway, 2009). Semantic memory is the other process that allows us to represent our experiences and build on our knowledge, and this is the process that gives humans a feeling of knowing. This feeling stems from finding the commonalities about the world and everything in it from related episodes. Therefore, continuing to expose ourselves to information that makes us consciously aware of the dangerous biases we hold will be necessary in order to relearn ways to eliminate these biases.

Considering the process of creating schemas, people are built through their surroundings growing up. Whether it be positive or negative, it shapes who we are now. For example,

Through the years I have noticed the world is full of people with strong biases towards one another. However, the world seems to only focus on the dominant population and their biases towards people of color, which quickly turns into racism in our society. The people act as if minority groups are the ones to create the problem and so building a bias against them is easy. Well, what society doesn’t notice is how minority groups are taught to be biased towards dominant groups also.

Picture this, you are a black woman with chocolate brown skin with crazy untenable curly black hair. You are getting up for school just to realize that being yourself isn’t what the people around you want. With those thoughts going through your mind you begin to get dressed. Putting on an average sweater because that is what everyone else is wearing, putting on the minimal amount of makeup because that is what you see the other girls wearing. Now you look down at the hair tie and hair straightener, which do you choose? Because society doesn’t accept your crazy afro hair. Choosing to throw it up in a slicked-back bun you move on to the next steps of slowly hating the fact that you are a woman of color. Do you know what the next step is? Looking in the mirror to make sure you look “presentable.” Looking yourself up and down finally stopping to look yourself in the eyes. Do you know what you see? You see all the wonder. You wonder about what it would be like for people to accept you for who you are. You wonder about what it would be like to wear what you want and just to be proud of who you are, a black woman. Then finally you wonder why. Why do you feel like you need to hide and pretend to be something you clearly aren’t. As you make your way to your front door you take a deep breath before walking out. Then bam! There it is, the reason you feel like this every morning, the woman that makes you feel this way. The woman that took everything that made you who you are and turned you into her and her daughters. Every day it was something new, “You should wear your hair like this. You should dress a little more like this. It would be so cute. You should read this book. I think you will really like it.” it takes you years to realize that she turned you into her, a white woman. She made you dress like her version of what was right, she made you think like her and all the white women around you, but most importantly she made you forget who you are and your cultural roots. Now guess where that leaves you? A woman with identity issues. You, a black woman no longer knows the power behind it. You don’t understand what it means to be a woman of color with such a strong history because a white woman said “ in order to fit in you should act more like the women around you,” well guess what they were all white women/girls. Now, because a white woman has made you feel down all your life, you’ve now created a bias towards a majority of the dominant population.

We all have biases within us, whether it be from an experience growing up or created through topics read on social media. The main point is we all have biases. So, what is it exactly that is happening in our minds that creates them?

The human cognitive system allows for the understanding of our external world, the creation of our internal representations, and the subsequent manipulation of those internalized ideas. This is what creates and maintains thoughts, beliefs, and memories of our life and knowledge about the world. However, our minds are designed for efficiency, thus there is room for error. Specifically, our minds are wired to create biases. We are constantly observing and taking note of every aspect of our lived experience, including what is presented to us by society, and while this process of schematization is evolutionarily helpful in many ways, it can lead to unintended consequences.

Through the process of schematization, our minds create sets of associations for everything in our world. Objects, characteristics, and emotions, positive and negative, are all interconnected in our internal web of associations. At any given moment, our working memory system can access this web through the episodic buffer, which allows us to draw on our previous experience to understand what is happening in the present (Baddeley et al., 2020). This is an efficient and helpful process; it gives us a feeling of awareness and allows us to navigate through daily life. However, because this process is often occurring below the surface of our conscious awareness, it can create associations that don’t necessarily reflect our sense of self. In a workshop about implicit bias, Professor Matthew Hunsinger said that “our mind mirrors our environment,” regardless if it is helpful, accurate, or valid. So when we watch a movie where all the main characters are white, and the antagonist “thugs” are people of color, our minds take stock of that. And when our cultural systems and standards of things like beauty or professionalism favor white people, our minds make those associations as well. An example that Professor Hunsinger used was if we get mugged and the person who attacked us was black, regardless of how we can consciously recognize that their race was unrelated to the crime, our mind will subconsciously associate those feelings of fear and danger with the experience and, therefore, with the characteristics of the person who mugged us. We create these associations without even realizing that we do, and it happens all the time. In fact, cognitive scientists like Laura Shulz argue that these associations start during early childhood, within our neural connections, through a process known formally as the Bayesian inference process. So if this process of inference and association is hard wired into our minds, what do we do when we need to change?

The first step to fixing our internal biases is recognizing that we all have them. Because of how our cognitive systems work, it’s pretty much impossible not to. The next step is taking some time to think critically about which biases we have and how they affect our behavior. Being conscious of our thoughts, specifically, those that are biased, when they appear and being able to identify them as inaccurate can help us to take back control of the associative nature of our mind. Sometimes we have to turn off autopilot and make conscious and effortful decisions to rewire our associations. When your automatic thought is negative, meet it with a positive one and, over time, that automatic thought will change to better fit your attitudes. After all, these associations that our mind creates are the product of cell assemblies in the cortex firing again and again. But that doesn’t mean we are stuck with them. The mind is efficient, yes, but it is also remarkably plastic and can undergo significant changes.

Understanding the systems associated with human memory is important in order to not only recognize specific biases held against target racial groups but to actively do something in order to change and eliminate these biases. We live in a world that provides an environment that unknowingly encourages racial biases, which results in people of color being so uncomfortable in their own skin that they are not able to be their authentic self for fear of judgment, disapproval, and ostracism by the majority. Our minds are structured in a way that allows these biases to happen automatically, but it is also structured in a way that gives us the ability to put an end to them. Recognizing episodic and semantic processes as ways of representing the information we take in from the surrounding environment, understanding how to reverse our bias-creating cognitive systems, and learning how our minds sort through the information we are given are all essential steps in allowing ourselves the opportunity to unlearn racial biases. The first step to changing the world we live in is changing our internal copies of it to better serve us and the people in our lives.

The Power of Memory Formation and Recall in the Fight Against Racism

The human mind is tested and challenged throughout every second of our lives. The mind is constantly absorbing information from the environment, processing it, and determining the appropriate next steps by activating a specific behavior, emotion, or feeling to help individuals respond to an original stimulus. Our minds are constantly in action no matter what situation we are in, and these environments are essential in the formation of our thought processes. Unfortunately, humans are surrounded by racial biases in almost any environment, making our minds more susceptible to absorbing information that could potentially cause harm to those around us if we are not aware of it. Although our minds are not perfect and cannot filter out biased information, they are extremely malleable. Understanding the processes that our minds utilize to form new information into memories and how these thought processes are then retrieved is essential to be able to make progress toward creating less subjective memory systems and aim to have our memory systems open and welcoming to differences.

First, to be able to understand the workings of the memory system it is vital to understand how the formation of schemas contributes to the associations we make from past experiences to our current thought patterns and behaviors. Schemas are the mind’s way of organizing information into integrated clusters that allows us to sort through our knowledge of the world around us. Schemas are useful because they allow us to draw inferences, make predictions for the immediate future, and adapt to changing environmental conditions (Baddeley et al., 2020). Being exposed to multiple experiences with commonalities and therefore creating neural assemblies that repeatedly fire is the way in which schemas are built. Upon further evaluation of schemas, Ghosh and Gilboa (2015) provide that schemas possess four “necessary and sufficient features” including associative structure, basis in multiple episodes, lack of unit detail, and adaptability (Baddeley et al., 2020). These four different features suggest that schemas consist of interconnected units, have information integrated from several similar events, consist of variability between the related events, and can adapt as they are updated when provided with new information (Ghosh and Gilboa, 2015). Understanding the structure and function of schemas helps us to be aware of the abilities we have as humans to form new schemas that do not involve racial biases. When we are exposed to environments that involve any form of racism, it is our job to be aware of the implications behind the message being portrayed and purposefully create thought processes that avoid these racial connotations. Bringing our unconscious biases that were formed by our surroundings to awareness will prevent us from acting in a way that is discriminating and harmful to our fellow human beings.

One of the most important aspects of memory to be aware of is its fallibility. Even though we have the ability to recreate these images in our heads that represent past experiences, these representations more than likely contain false information, no matter how accurate they may seem. Martin Conway and Catherine Loveday explain the importance of recognizing that memories are mental constructions, they are not reconstructions (2015). The representations of past experiences that humans create can hold an amount of accuracy, but our minds are unable to reconstruct events in a way that depicts them literally. Conway and Loveday explain that “. . . although they may to some degree accurately represent the past they are time-compressed and contain many details that are inferred, consciously and non-consciously, at the time of their construction” (2015). This idea explains that all memories are false to a certain extent because they do not replicate our past lived experiences exactly as they happened.

Conway and Loveday explain memory accuracy as having two dimensions: correspondence and coherence. Correspondence refers to a memory representation that is true to the event, therefore it corresponds strongly to a previous experience and coherence refers to a representation that is true to the self, therefore is coherent with other memory representations and self-concepts (Conway & Loveday, 2015). Although it may seem like a flaw in our memory systems to not remember every detail of our lived experiences, it is important to understand that a perfect memory is not the end goal. The human memory system functions the way that it does so that we can create personal meaning from our lived experiences and use these meanings to “make sense of the world and operate on it adaptively” (Conway & Loveday, 2015).

One of the most important ways humans have used their memory to adapt to their environment and simultaneously create a space for themselves within that environment is through autobiographical memory. Autobiographical memory is the accumulation of knowledge surrounding personally relevant events and information (Baddeley et al., 2020). Through episodic memories, we can build a framework of who we are, who we used to be, and who we see ourselves as in the future. Through semantic memories, we can attribute certain facts and knowledge about our world to our self-concept and use that knowledge to aid in our survival, physically and emotionally. Autobiographical memories serve a very important purpose in our lives. Not only do they help us remember what to do when we lock ourselves out of our car, but they allow us to connect with other people in social environments (Baddeley et al., 2020). Reminiscing about the past with friends and family is a huge part of social interaction and helps develop strong relationships. Additionally, telling stories about exciting or interesting events from the past can help you to relate with someone you’ve just met. From an evolutionary standpoint, these social connections are important for making allies and having someone you can rely on when survival is being tested. In the modern world, however, when evolutionary goals aren’t as important, our autobiographical memories help us to maintain relationships and understand ourselves as independent individuals.

Culture is an important influence on our autobiographical self, as it often mediates how we remember events and how we view ourselves as part of a collective group. Culture is created by the people within it through rituals, customs, traditions, and stories. None of these things would be possible without the capabilities of our memory systems. In this way, autobiographical memory serves a collective purpose, in addition to its individual function, and helps to perpetuate cultural values and beliefs. One way we can see this is through cultural differences between Eastern and Western cultures. Accessibility, or ease of recollection, of autobiographical memories, specifically early childhood memories, is easier for Western individuals, likely due to the emphasis on individuality and the cultural importance of having a strong sense of identity (Ross & Wang, 2010). Conversely, “East Asian cultures foster a relational view of the self that focuses on an individual’s interconnectedness with others and place within a network of relationships” (Ross & Wang, 2010). These cultural differences may provide a different structure for autobiographical memory and self-concept but ultimately serve the same function. Our memories are shaped by the place we live, the language we use, and the people we interact with. And all of these aspects contribute to the lifelong development of our individual self.

As we progress through life, we create an account of experiences that ultimately define who we are. These episodic moments are organized into autobiographical schemas that increase in content and efficiency as we age. This is how we form our life narrative, a collection of emotionally charged, personally important, and culturally relevant events or pieces of information that give us a sense of who we are and how we got there (Baddeley et al., 2020). These events often include things like marriage, going to college, and family vacations. But they can also include things that are charged with negative emotion, like the death of a parent or childhood abuse. All of these memories seem to accumulate to form our identity and give us somewhat of an explanation for who we are. It is in this way that we see how important autobiographical memory is for normal functioning. Without a collection of memories from our life, we can lose that sense of self. This is common for amnesia or dementia patients; if you can’t remember or recognize the important events and people in your life, you can’t maintain your representation of who you are (Baddeley et al., 2020). This representational self is the basis of autobiographical memory and gives us the ability to relate to others and think introspectively. It also guides our behavior in ways we sometimes fail to recognize and can sometimes create conflict between ourselves and others.

Naturally, people aren’t always accepting of new information, especially if the information provided is contrary to beliefs or ideas that are an integral part of their identity or requires changes in their actions. All a person needs to do in order to broaden their knowledge about the importance of racism is to step in the direction of growth. The best way to connect with others is to have more of an understanding of structural racism, meaning how the policies, practices, and protocols include white people and exclude people of color. Over the years we have learned multiple different ways to exclude individuals in social settings, even if it was done without meaning to. In our everyday actions, we tend to exclude individuals because of the information we have encoded throughout our lives. We create biases and when a person fits said bias we tend to forget all about them. When taking into consideration racism, society created an ideology about how it is meant to downgrade people of color, and so excluding people became a part of our history. These socially constructed ideas about race and people of color have a direct influence on how we form our schemas and association networks, which is why it is important to recognize socially charged influences in order to challenge our previously encoded schemas.

According to Schacter (1999),

Transience-forgetting over time- can occur even when an event or fact is initially well encoded and remembered immediately and can occur even when we deliberately search memory in all attempts to recall a specific event or fact. However, a good deal of forgetting likely occurs because insufficient attention is devoted to a stimulus at the time of encoding or retrieval or because attended information is processed superficially.

We know how to treat others, but because we forget or ignore our teachings of how-to, we create “isms” in the world. This is why a personal commitment to growth is the most important step a person can take in order to change their ways of thinking about others. In order to prevent transience from perpetuating implicit bias and racism, here’s what we must do: we as people need to reflect back on what we’ve heard someone say, affirm what they say that could promote equity and inclusion, bridge with a question that makes the other person think about a different perspective, to help them see at a deeper level. Through Schacter, we understand people eventually choose to forget or naturally forget what we learn over the years. Therefore, in order for one to showcase growth, we need to understand how others think.

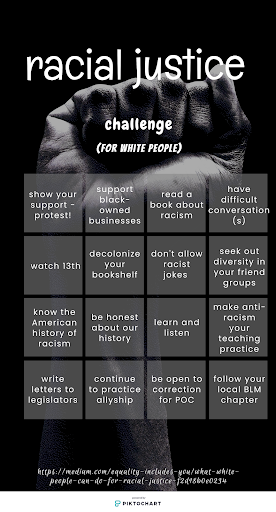

At a cultural level, we have different jobs to do. People of color have had to do too much for too long, to “fit in” to a culture that does not respect diversity and is not uniformly inclusive, whereas White people haven’t had to think at all about their privilege. Many people of color have to conform to the dominant culture (whiteness) in order to fit into society. Many conform through perfectionism, people of color are needing to remind themselves mistakes are okay and they don’t have to be the best, it is okay to ask for feedback, especially in a lesson about justice, paternalism, they know the people who have power seem to be those who have been “in charge” longer. Those who are in a higher position than they force people of color to be silent. People of color are trying very hard to use their voice and let others know they do have something to offer in experience and conversation. When a member of the dominant culture says “I don’t see color,” it is just as much a slap in the face as saying “racism doesn’t exist.” It is less of forgetting what we have learned in schools and through parental teachings and more of having avoidant thoughts. Many individuals choose to avoid the obvious problem, racism, as to not be responsible for their actions or to be forthcoming of their peer’s actions. One can’t improve their growth if they are refusing to even acknowledge racism even exists. This needs to change: people of color deserve a rest and White people need to start committing to changing their schemas and their actions.

How to change:

-

- Identify your personal morals and beliefs

- Engage in Self-Reflection

- Exercise empathy

- Identify one’s biases and their potential impact on others

- Broaden one’s viewpoint and educate others

- Step in the direction of growth

- Understand how your own self-concept affects your thoughts, feelings, and behaviors

- Be aware of how these thoughts, feelings, and behaviors affect systems, policies, and most importantly – the human beings around you

The overall process of becoming aware of our internal thought processes and coming to terms with the fact that they might not be what we had originally anticipated is crucial in the attempt to better understand our self-concepts that form our autobiographical memories. Utilizing what we now know about our self memory systems to change our schemas if they are at any level of threat to other human beings is not an automatic process. It will take time, but if one is willing to put in the effort to shift their focus to an anti-racist mindset we can continue to spread the other of this process so that others have the resources to change their biased thought patterns as well. As Conway and Loveday advise, as humans we must challenge ourselves to focus on correspondence more than coherence in our everyday lives. If we do this, our schemas will be modified to more accurately reflect the realities of people of color. Emmanuel Acho, former NFL linebacker and current social justice advocate stated, “Proximity breeds care and distance breeds fear . . . there is not enough proximity between people who don’t look like each other. . . there’s a lack of care or lack of empathy, and there’s a heightened amount of fear” (2020). When we use the opportunity to step in the direction of growth, we listen to others and hear their experiences. We immerse ourselves in diverse environments and we don’t disregard a single thought, feeling, or behavior that a person of color has experienced due to the injustices they have faced. When we seek proximity, we seek care. We allow ourselves to truly see the stressors that people of color have had to face day in and day out, and we will be better equipped to start making positive changes in ourselves and in our society.

About the Authors

Brittany Krechter. I am a 21-year-old Pacific University Undergraduate student majoring in Psychology with a minor in Anthropology. Taking Memory and Mind (PSY 314) and creating this project has had an incredible and unexpected impact on my thoughts and feelings about cognition, memory, and racism. I never would have imagined that this class would have had such an influence on my personal life, as it has helped me recognize my own internal biases and given me the tools to engage in anti-racism. My hope is that this collection of papers can be an informative and inspirational resource for others to do the same.

Nina Nova. I am a 21-year-old Pacific University undergraduate student majoring in Psychology with a minor in Health and Wellbeing. Having the opportunity to take Memory and Mind and working on this project has really helped me grow as a person and strengthen my awareness of others around me. I now understand I have my own personal biases I need to work on, and how to educate others on theirs. I feel more connected to my internal thoughts and being sure to take into consideration how others have an untold story that makes them the way they are and how to productively listen to them.

Carli Feist. I am a 21-year-old Pacific University undergraduate student majoring in Psychology in hopes of becoming an Occupational Therapist. I have been grateful to study Psychology and be exposed to the different aspects of human psychological processes, but taking Memory and Mind opened my eyes to so much more. Utilizing the working memory system in order to become more anti-racist, anti-ableist, and anti-sexist has allowed me to grow in so many areas not only in academia but in life in general. I am going to use the knowledge and awareness gained from this class to spread knowledge and awareness to others, in hopes of making a change in their thought processes and help others resurface unconscious biases and restructure thought processes to become more accepting and inclusive.

References

Acho, E. (2020). A conversation with the police – Uncomfortable conversations with a black man Ep. 9. Youtube. doi: www.youtube.com/watch?v=pM-HpZQWKT4.

Baddeley, A., Eysenck, M. W., & Anderson, M. C. (2020). Memory (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Daniel Kahneman. (2010, March 2). The riddle of experience vs. memory [Video]. TED Talks. https://www.ted.com/talks/daniel_kahneman_the_riddle_of_experience_vs_memory?language=en

Conway, M. A. (2009). Episodic memories. Neuropsychologia, 47, 2305–2313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.02.003

Conway, M. A., & Loveday, C. (2015). Remembering, imagining, false memories, & personal meanings. Consciousness and Cognition, 33, 574-581. Doi: dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.con.cog.2014.12.002.

Doolittle, P. (2013). How your “working memory” makes sense of the world [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/peter_doolittle_how_your_working_memory_makes_sense_of_the_world?

Hunsinger, M. (2020, October 29). Implicit Bias Workshop [Zoom Presentation]. Pacific University.

Kleinknecht, E. (2020). Neuroscience Foundations PowerPoint, Week 4.

Ross, M. & Wang, Q. (2010). Why we remember and what we remember: Culture and autobiographical memory. Perspectives in Psychological Science, 5, 401-409. Doi: 10.1177/1745691610375555.

Schacter, D. L. (1999). The seven sins of memory: Insights from psychology and cognitive neuroscience. American Psychologist, 54(3), 182.

van Kesteren, M. T. R., Brown, T. I., & Wagner, A. D. (2016). Interactions between memory and new learning: Insights from fMRI multivoxel pattern analysis. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 10, doi: 10.3389.fnsys.2016.00046.

van Kesteren, M. T. R. & Meeter, M. (2020). How to optimize knowledge construction in the brain. NPJ Science of Learning, 5; doi: 10.1038/s41539-020-0064-y.

Wang, Q. & Ross, M. (2007). Culture and Memory. In The Handbook of Cultural Psychology. S. Kitayama and D. Cohen, eds. The Guildford Press, New York & London.