7 Access Alone Isn’t Enough

Understanding and closing the college digital divide

Benjamin D. Remillard

If we are going to learn from our teaching and learning experiences during the pandemic, we have to understand the socio-economic forces behind the digital divide and how it will continue to affect our classrooms in the coming decades. This chapter will show that despite the tenacity of these issues, we can begin to implement holistic digital pedagogies at the classroom level that recognize, assess, and address the opportunity gaps our students face. While we may not have the power from the confines of our lecture halls to overthrow the systems that lead to these inequalities, we can narrow some of those divides by taking small, learner-centered steps toward making technology more accessible and impactful for our students.

America’s Digital Divide

To better understand the root of the issues we see at the college level, we must understand how various gaps begin when students are still enrolled in primary and secondary school. These trends are easy to track using standardized tests, where wealthy students consistently outscore their peers in lower income brackets (Zumbrun, 2014). University of Connecticut researchers have shown that when it comes to the online research and comprehension gap between the richest and poorest students, by the time those students get to middle school there is already a year’s worth of learning differences separating those groups (Braverman, 2016). Students of color are especially hard hit by this economic divide (Dixon-Román et al., 2013). When it comes to specific skills like reading and math, a 2016 report in the New York Times noted that, “Children in the school districts with the highest concentrations of poverty score an average of more than four grade levels below children in the richest districts,” disproportionately affecting students of color (Rich et al., 2016). These disparities grow as students age.

This all relates to what sociologist Robert K. Merton coined the Matthew Effect, the basic principle of which is that the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. A similar principle applies to technology. Lloyd Morrisett, a founder of the Children’s Television Workshop, first coined the term “digital divide” in 1996 “to describe the chasm that purportedly separates information technology (IT) haves from have-nots,” where the gap between them creates inequality (Eubanks, 2011). As Neil Selwyn argues, technology reinforces the Matthew Effect’s impact on the digital divide (cited in Braverman, 2016). Here is where gaps will develop, where “high-achieving” students build on previously developed knowledge and skills while the “lower-achieving” students potentially flounder due to lack of access, lack of education, or a combination of both. Focusing on achievement alone, however, misses the bigger issue.

Educators are shifting away from understanding these divisions as “achievements gaps” by understanding them instead as “opportunity gaps.” Through the former lens, the differences in educational outcomes between students and school districts are often attributed to deficient work ethics, lack of “grit,” etc. The latter lens, however, encourages us to understand the inequitable access to educational tools and experiences marginalized students face. This shift in terminology takes the onus off the students by focusing instead on the unbalanced systems that discriminate against those students in the first place (Mooney, 2018). Simply increasing access to technology, however, will not solve for these opportunity gaps.

Increased Access to the Internet ≠ Equitable Access to Opportunities

A 2013 report by the U.S. Census Bureau noted that smartphones were reducing the internet-use-gap between different racial and ethnic groups. This trend had been building for a few years when, during the last quarter of 2010, smartphones outsold PCs for the first time (Smart Phones Outsell PCs For The First Time, 2011). This has served as a cost-effective crutch in education. As noted by NPR in 2016, a quarter of low-income families with school-aged children had, “only a mobile device for internet access. Among families living below the poverty level the proportion rises to a third. And it’s highest at 41% among immigrant Hispanic families in particular” (Selyukh, 2016). This begs the question: how can you complete all your school assignments with just a smartphone, especially if it’s not a high-quality smartphone?

There is a concern in many low-income school districts that if you require students to complete homework online or require them to use specific computer programs, not all of their students have adequate access to that technology at home. Prior to the pandemic roughly 17% of primary and secondary school students in the US did not have access to computers at home, and 18% did not have access to at-home broadband internet (with expense being cited as the main reason for a third of those) (Associated Press, 2019). As is often studied, this divide is most apparent when examining access between rural and urban residents. In 2018, for instance, roughly 51.6% of rural US residents had 250/25 megabits per second internet access, while 94% of urban residents had the same (Lai & Widmar, 2021). Even in urban spaces though there can be a serious divide between the digital haves and have-nots. A recent paper argues that digital divide can at least be partially attributed to 20th century housing policies where, “the exclusionary property ownership and residential segregation technologies developed by administrators of the HOLC [Home Owners’ Loan Corporation] and the FHA [Federal Housing Administration]” contribute to “current differences in students’ geographies of opportunity as they relate to broadband access” (Skinner, et. al. 2021)[1].

As more attention has been paid to what has increasingly been referred to as digital redlining, so too has more evidence of it and its effects have been brought to light. As an example, a 2017 analysis of FCC data regarding AT&T’s digital infrastructure plans “strongly suggest [that AT&T] has systematically discriminated against lower-income Cleveland neighborhoods in its deployment of home internet and video technologies” for over a decade. This includes the company’s decision to withhold fiber-enhanced broadband from “most Cleveland neighborhoods with high poverty rates.” This had a double effect whereby residents in those lower-income neighborhoods were not allowed to apply for AT&T’s “Access” discount rate program because they lacked the minimum download speed required for the program. This then required those residents to rely more heavily on expensive (and slower) mobile broadband (Stanton, 2017). Such disparities, especially in areas with scant preexisting digital infrastructure and/or competition between service providers, limit students’ opportunities while reinforcing the digital divide (Lai & Widmar, 2021).

From a college educator’s perspective, we see this struggle perhaps most often among our commuter and community college students who don’t always have 24/7 access to wi-fi like what is available for students living in residence halls. As noted by NPR, if low-income students do not have wi-fi at home, or if they are on a metered plan, they are going to run into roadblocks (Selyukh, 2016). Even if those students can access a coffee shop or public library where they can use free wi-fi and maybe even a cheap printer, those places eventually close, shutting off access to those needed resources. Despite increased access to the internet and mobile technologies, then, the historically rooted gaps in accessibility continue to separate our students (Cortez, 2017).

While access to online services and digital technology improved during the first year of the pandemic as schools and governments scrambled to ensure continued learning, the fact remains that millions of students remained without reliable access to computers and/or wi-fi (Richars et al., 2021). How schools dealt with that transition varied, again, along socio-economic and racial lines.[2] While we can probably guess what impact this will have, the pandemic’s long-term effects on education may not be fully understood for years to come. As educators, we can’t solve these systemic issues on our own. We can, however, avoid perpetuating these inequities by creating meaningful learning experiences for our students that address these preexisting opportunity gaps and the resulting disparity in skills.

The Importance of Digital Literacy in a Digitally Divided Age

In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire asked, how do you create a learning environment that does not simply educate, but empower learners? One of Freire’s most important contributions is the notion that education should not be a top-down, sage-on-a-stage approach where we simply lecture at our students about various topics—otherwise known as the banking system of knowledge—because they need to meet government or university standards/learning outcomes. In high school or college-level classes, this is like making them learn how to use Excel, or a research database, or how to read a scientific article, without helping them understand how elements of those experiences are applicable in other parts of their lives. Freire instead endorsed the empowerment of students by working with them through an educational experience rooted in dialogue, by creating a system that works to their benefit (Freire, 1970).

This process will look different when taking into consideration the needs of different students, educators, and institutions. To borrow from a different writer while keeping in this vein, Sumun L. Pendakur advocates for educators to adopt, “a reflective, identity-conscious framework that grapples with the hegemonic nature of power” both in and outside of our particular universities. As Pendakur suggests, we need to become “empowerment agents” who better support students on the margins and their particular needs (Pendakur, 2016). It is on us as educators, then, to understand how opportunity gaps affect our students, to identify what gaps need bridging, and then to give them the tools necessary to create the desired changes they wish to see in their lives based on their own decisions, input, and professional and personal interests.

Many colleges have implemented 1:1 laptop, computer, or iPad programs to remedy any gaps they see in their technical offerings, by making sure all students have access to the technology they need (EdTech Staff, 2021). But we often forget that we still need to teach students how to best use those devices if those tools are going to make a difference in their lives and education; access alone isn’t enough if they are going to use those devices to play games or watch Netflix (Eubanks, 2011).[3] This increase in accessibility also means little if faculty are not being trained or incentivized to incorporate these tools into their curricula.[4] As Sean Michael Morris has suggested, when we consider what critical instruction design looks like, “digital tools, strategies, and best practices are a red herring in digital learning” instead of asking “What tool will we need?,” we need to instead ask, “What behaviors will need to be in place?” (Seam Michael Morris, 2018b).

To begin, we need to be clearer about how students do and don’t use technology, especially at the college level, where we often assume students are more capable and technologically savvy than they actually are (Braverman, 2016). We often talk about students being on their phones in the middle of our classes, whether it’s on TikTok, fantasy football, a mobile game, etc. What this shows is that they are mobily literate, which is “the ability to navigate, interpret information from, contribute information to, and communicate through the mobile internet, including an ability to orient oneself in the space of the internet of things (where information from real-world objects is integrated into the net) and augmented reality (where web-based information is overlaid on the real world)” (Hockly et al., 2014). That is, students who use their phones a lot are good at using their phones.

Having a good phone, though, rarely helps students when it comes to learning the higher-level digital skills we expect them to develop for college—whether it be writing a report and formatting it using a word processor, doing digital research, pulling/analyzing/synthesizing information from a variety of sources or source types, or collaborating with their peers on more innovative technology to create websites, blogs, podcasts, etc. On their end, students sometimes take for granted what they encounter on their phones, not always understanding or examining through a critical lens how—as Safiya U. Noble and Ruha Benjamin have studied—the internet amplifies hatred, racism, and sexism (Noble, 2016). Mobile literacy, then, does not by itself help students learn. These students are only going to have the skills necessary to succeed at the college level if steps are taken to widen their perspectives on and use of technology in various forms. This all ties into another type of literacy.

Information literacy focuses on, “the ability to locate, access, evaluate, and use information that cuts across all disciplines, all learning environments, and all levels of education” (Standards, 2000). This is something we often dwell on in academia, especially as it relates to things like finding articles and books for projects, or the analysis of those resources. Reflecting on my own college experience a little over a decade ago, I don’t even need a full hand to count the few teachers who took time out of their lecture schedules to walk us over to the library, to go over how to do research on the college’s databases, how to use the school archives, etc. I can’t emphasize enough just how important those rare building-block experiences were for me as a History major. When we talk about information literacy though, and when we talk about the importance of technology in our lives, those skills and learning opportunities are essential not just for Liberal Arts majors, but for all our students.

Regardless of our individual disciplines, we as educators need to create systems that create more equitable learning environments for our students. Stanley Aronowitz noted that literacy (writ-large) for Freire, “was not a means to prepare students for the world of subordinated labor or ‘careers,’ but a preparation for a self-managed life (2009, cited in Giroux, 2010).” bell hooks, building on Freire, similarly argued that education is “about the practice of freedom,” creating classroom environments in the process where, “students are often presented with new paradigms and are being asked to shift their ways of thinking to consider new perspectives,” especially those related to class, race, and gender (hooks, 1994). Educating students today should similarly adopt and encourage new technology frameworks and mindsets by simultaneously demonstrating to our students the opportunities in these systems, as well as the malleability and danger in these systems, and how inequitable digital opportunities can harm them and others. This sort of critical digital pedagogy, in combination with providing students with the tools they need to close preexisting digital opportunity gaps, can give students an education they can carry over into the rest of their lives. This is where a third type of literacy comes into play.

Digital literacy is about more than just the skills we want students to develop—it’s the application of those skills and knowing when and how to incorporate them into people’s everyday lives. Maha Bali argues that digital literacy focuses on the when, why, who, and for whom you use these skills and tools. These are the deeper, more critical questions we have to get students thinking about if we really want them to excel with digital technology and online mediums. After we know they’re comfortable with those tools it’s connecting to questions like, “When would you use Twitter instead of a more private forum? Why would you use it for advocacy? Who puts themselves at risk when they do so?” (Bali, 2016). The point is to go beyond the academic application of those tools and get to a point where that technology can affect change in their personal and professional lives.

To put it another way, this knowledge (not just information, but the application of that information) has to change how our students interact with the world around them (Chetty et al., 2018). It does not matter, for instance, if your university offers four different workshops on how to use a specific program like Word, Photoshop, or Excel; probably every educator has stories of offering opportunities that students didn’t attend or find valuable. What matters is helping students close opportunity gaps by demonstrating how those digital services have real-world uses. Using the example of Excel—students won’t care about learning how to write formulas and set-up tables if they’re just elements to a core curriculum class they need to pass to graduate. What they will care about, though, is learning how to use those techniques to calculate their college loans and interest rates, or using those techniques to create a budget so they can afford to study abroad, or how to keep track of expenses and proceeds from a Greek-life fundraiser, etc. Or, maybe that tool can be used to help a student who lives in an apartment off campus—or who has a family, or who struggles with their money, etc.—make a budget and forecast their expenses over time so that they can become financially independent.

This more holistic investment in our students has to be rooted in dialogue and a desire to help our students grow based on their needs. This aligns with bell hooks’s call to action (building on the words of Tich Nhat Hanh) regarding the importance of “practice in conjunction with contemplation,” where education should call “on students to be active participants, to link awareness with practice” (hooks, 1994). It is only once we get to know our students that we can help them apply the tools, skills, and knowledge at our shared disposal. For those students on the margins, we can work together to buck the institutions and systems that let this digital divide grow, where they can find a whole swath of new applications for various technologies and become more independent, life-long learners. What that interaction and focus looks like will be different depending on your discipline, but there are some basic approaches we can all take.

Teaching Strategies for Closing the Digital Divide

There’s a lot we can do to help our students close the digital divide. But before we can dive into metacognition, various literacies and learning exercises, low-stakes assessments, or advanced semester-long projects, we need to assess for the basics: what do students already know/don’t know how to do? In the same way that we wouldn’t start a History course on World War II with the Battle of Stalingrad, or begin a Physics class with Newton’s Third Law of Motion without also going over the First and Second, we also shouldn’t start off our semesters by expecting students to complete assignments or act in digitally responsible ways that they don’t have any context for or experience with. I’m referring, first off, to the skills that should have been (and probably were) covered during their first-year student orientation.

Anyone who has ever taught at a university can tell you about the student who never responded to their emails, inevitably leading to struggles and even conflict toward the end of the semester. Assessing whether students are accessing their email or their online class portal by having them complete beginning-of-the-semester checklists or ungraded quizzes, for instance, can establish an important baseline for the rest of the semester, helping us create better interventions and learning opportunities as they arise rather than after it’s too late. These sorts of exercises are valuable both for first-year students still acclimating themselves to college or for upperclassmen who never developed the habit of checking their email. In either case it’s a red flag that there may be some other gaps in their knowledge that need to be addressed.

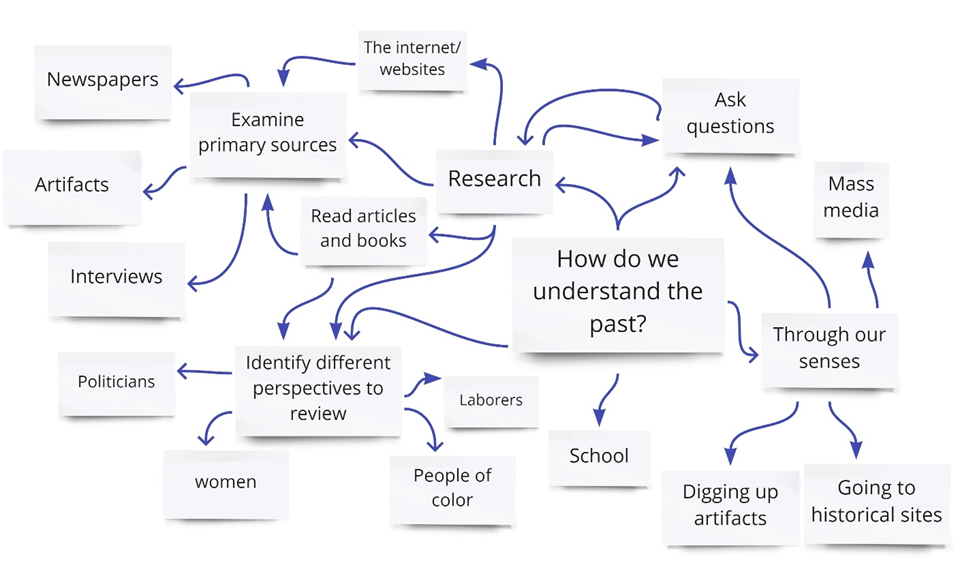

From there we can move on to assessing their literacy and research or discipline-specific skills. Similar to the above, we can keep the emphasis here on making these ungraded or low-stakes assessments, where the focus is on improving student skills and helping them grow rather than on potentially punishing them with low grades. It could start as an open-ended question or a low-stakes homework assignment, where you ask them, “How do you determine whether a source is reliable or not?” More helpful, though, is if they complete more interactive exercises like concept maps, where they draw in the center of a paper the central idea, like “How do we understand the past?” or, if you are working toward a specific assignment, “How do you complete a research paper?”

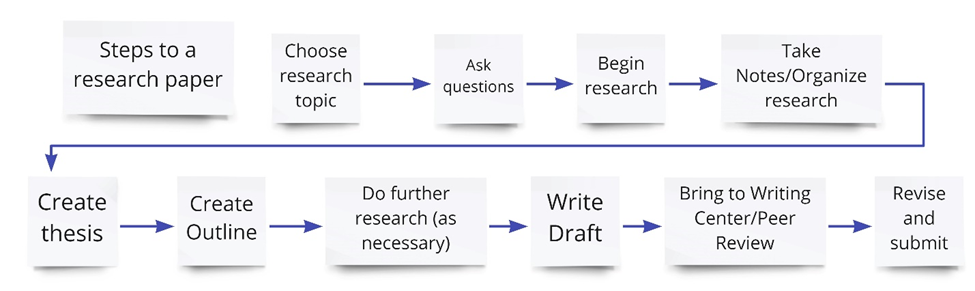

If you have an assignment in mind, like a research paper, from that central point they can expand out into the various elements they might need to complete the assignment, like finding and evaluating sources, taking notes, synthesizing information, writing a rough draft, etc. Given the emphasis on dialogue earlier, such an exercise can then be workshopped with the full class, where you compile their answers together on the board in a more comprehensive map. From there you can determine whether they have a sense for what you want them to do, allowing you to provide further exercises like sequence chains, where you can string those various elements of a research project into an order they can follow.

Individual-turned-group exercises like these can stimulate further conversations both in and out of class. In the example of a research paper, when a student notes the need to gather sources, you can push them further (perhaps even with the help of a school research librarian)—what is an acceptable resource for a research paper? Depending on your discipline, is an article for a peer-reviewed academic journal or news organization expected? What about .edu or .gov webpages? Does recency of the piece matter?

Maybe this can stimulate a deeper conversation about the biases in specific search engines, their manipulability, the harmful ways they can collect data, and the pros and cons of using them compared to, for instance, a college library database.[5] Perhaps this leads to an exploration into how even college databases can be problematic, where restrictive acceptable use policies lead to a different form of digital redlining that disproportionately affects community college students (Gilliard & Culik, 2016). All of these topics are important entry points for getting students to think more broadly about digital literacy, accessibility, and the impact all these things have on their and others’ lives.

Many Composition and First Year Seminar teachers are already accustomed to getting students to think more metacognitively while training them to do work across different genres, helping them understand the wide reach and applicability of their writing while using educational tools in new ways. Why can’t every class do that, especially if what we want them to do is still academically rigorous, or mimics what professionals in our fields are doing out in the “real world,” outside of just writing papers for niche audiences? As an historian I can look at how many professionals are creating blogs, engaging with audiences on Twitter, doing podcasts or vlogs, creating pop-up museums in the middle of cities or campuses—all of which can become engaging assessments and content to dive into with my students while acclimating them to the wider uses of the technology at their fingertips.

The important part here is shifting those assignments and curriculum so that students are going beyond passive consumption of media/content. Without naming names, we can probably all think of “innovative” tools textbook publishers provide to help assess student learning, like ready-made online quizzes. These tools, though, usually just amount to extra layers of digital surveillance, where students check-off boxes in an online portal and the scores are reported to the instructor with metrics measuring accuracy, depth of comprehension, time on task, etc. While these sorts of tools may encourage a banking model of education, they do not engage with our students or help them become more independent learners.

If we are going to use technology to help our students learn, and to help them close digital opportunity gaps, we have to go about it in a way that encourages them to engage with their work and become active producers of knowledge, where they can think more critically about their work, the mediums through which they operate, and the wider contexts for their work (Bensen, 2015). This can and should tie into the higher end of Bloom’s Taxonomy (and Freire’s disdain for the banking method in education), of going beyond just standardized tests and assignments by instead making students assess, synthesize, and create new works that are informed by their own experiences, interests, and skills.

Take the discussion forum, a tired medium designed as much to measure online or hybrid-class attendance as it is about class participation (Morris & Stommel, 2018). The standard model asks students to post an initial post early in the week and then follow it up with one or two response posts of a shorter length later in the week. Despite our attempts to avoid vapid agreement and repetition of ideas, these forums rarely simulate the discussions that would happen in face-to-face classes. As such, they usually reinforce being rewarded for meeting the bare minimum (citing x-number of sources, writing at least z-number of words, etc.).

We can and should reshape online discussions by encouraging students to stretch their creative thinking muscles and by designing these assignments to mirror online and social media forums they likely interact with on a daily basis—though in a more thoughtful way. One idea I experimented with at the outset of the pandemic was having students finish each of their initial discussion posts with a question to their online classmates. The question could relate to the specific sources I asked them to read, the topics of the week, or even bigger-picture questions that analyzed course themes. As part of their response post each student was required to address a peer’s question. The production of and answering of these questions generated more critical thinking and reference back to that week’s primary and secondary sources (and lecture videos) than what I am used to seeing. These question-and-answer sections also provided me with more opportunities to address confusion around specific topics, to connect to the works of other historians, and to make the forums feel more like a place where ideas were exchanged rather than just act as a chance for me to grade attendance.

Another strategy I’ve incorporated to make this assignment more interactive has been to ask students, as part of their initial response, to connect some of that week’s readings to a relevant current event. Part of this requirement asks that they find a reliable news source and link to it in our online forums. In an anthropology class that could involve an article examining the effects of climate change on coastal communities. In a history class it can take the shape of connecting debates during the Constitutional Convention to debates today around the size and scope of the federal government. In a politics or sociology class the options are probably limitless given how tuned-in those courses are to current events. The point is to regularly assess and build on students’ online information literacy skills, making them find, evaluate, and relay reliable information while connecting to that week’s lesson in insightful and engaging ways.

The table below includes just a few other interchangeable examples to show the sorts of learner-centered digital and hybrid assignments that can stimulate creativity, critical thinking, and life-long digital literacy skills while still meeting the sorts of learning goals and outcomes our universities stress. Each of these provides opportunities for student choice, encouraging them to pick topics that drive their interest and perhaps the paths they want to pursue after college. If properly emphasized, our digital and hybrid assignments can provide students with an appreciation for a variety of new skills and outlooks, where the internet, its forums, tools, archives, etc., all become something useful and potentially life-changing, rather than act as “trillions of lines of code” no better than “flotsam” scattered across the web (Morris, 2018a).

| Putting Theory into Practice | Science/ Math | History | English | Anthropology | Sociology | Political Science |

| Assignment | Create a textbook with experiments for middle/high schoolers | Record a song about historical figures (as a satire, a rap battle, a ballad, etc.) | Create a blog for your semester’s worth of work | Develop a podcast episode on a course topic | Create an online questionnaire for a sociological study | Establish a digital archive/ exhibit of presidential tweets on a topic |

| Digital Skills Developed | Digital design/ editing/ publishing | Record/edit video/music on popular online forums | Web design/editing | Incorporate audio from interviews, edit into a presentation | Web design, online promotion techniques, data analysis | Social media analysis, data retrieval, web design |

| Course Objectives Reached | Create/solve average to complex scientific/ mathematic problems | Demonstrate understanding of competing historical viewpoints | Curate semester’s work into a portfolio, demonstrating semester-long writing development | Incorporate ethnographic fieldwork into a presentation | Create research study accessible to a large test population | Identify/ compile government information on perspectives and topics |

And to be sure, this responsibility doesn’t need to fall just on the teacher’s shoulders alone. Multiple studies exist that emphasize the role of librarians in digital and information literacy training. That kind of partnership can help reduce some of the sage-on-a-stage mentality in our classrooms. The research points to the notion that if students receive information and digital literacy training in a more collaborative manner, and if they are receiving those lessons from different parts of your institution, they might benefit more from those opportunities while bringing them all up to a similar baseline (Bensen, 2015).

Likewise, IT department trainings are another wonderful set of opportunities for collaboration. Having attended many of them over the years I know firsthand how thorough and attentive those staff members can be when it comes to helping our campuses better understand the tools at our disposal. As teachers we can support those endeavors with more than lip service by including those opportunities into our own lessons, by having guest speakers, by offering our own how-to lessons and materials, or even by providing class waivers if a student needs to attend a workshop. The infrastructure to support our students is already at our finger-tips—we just need to put it to use.

Conclusion

We don’t need students to rely on Microsoft Word to create scholarly projects; we don’t need to live and die by PowerPoint presentations; we don’t have to settle for some of our students graduating with the same general skills (or lack thereof) they entered our classes with. As Ruha Benjamin suggests, we need to learn from the experiences of the Coronavirus pandemic’s effect on education, and that “without a deep engagement with critical digital pedagogy, as individuals and institutions, we will almost certainly drag outmoded ways of thinking and doing things with us” (Benjamin, 2020). By expanding how we think about digital skills and classrooms, and by providing students with the opportunities to nurture skills and mindsets they can use for the rest of their lives, we can do a tremendous amount of good in at least starting to close digital opportunity gaps and the digital divide.

References

American Library Association (2000). ACRL standards: Information literacy competency standards for higher education. College & Research Libraries News, 61(3), 207-215. https://crln.acrl.org/index.php/crlnews/article/view/19242/22395

Associated Press (2011, February 8). Smart phones outsell PCs for the first time. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/smart-phones-outsell-pcs-for-the-first-time-7330519/

Associated Press (2019). Homework gap’ shows millions of students lack home internet. NBS News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/homework-gap-shows-millions-students-lack-home-internet-n1015716

Bali, M. (2016). Digital skills and digital literacy: Knowing the difference and teaching both. Literacy Today, 4(33), 25.

Benjamin, R. (2020). Foreword. In J. Stommel, C. Friend & S. M. Morris (Eds.), Critical digital pedagogy: A collection.

Bensen, E. (2015). Multimodal composing across disciplines: Examining community college professors’ perceptions of twenty-first century literacy practices [Doctoral Dissertation, Old Dominion University]. ODU Digital Commons. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds/5/

Braverman, B. (2016). The Digital Divide: How income inequality is affecting literacy instruction, and what all educators can do to help close the gap. Literacy Today, 33(4).

Chetty, K., Qigui, L., Gcora, N., Josie, J., Wenwei, L. & Fang, C. (2018). Bridging the digital divide: measuring digital literacy. Economics, 12(1), 20180023. https://doi.org/10.5018/economics-ejournal.ja.2018-23

Cortez, M. B. (2017). 21st-Century classroom technology use is on the rise. EdTech Magazine. https://edtechmagazine.com/k12/article/2017/09/classroom-tech-use-rise-infographic

Dixon-RomÁN, E. J., Everson, H. T. & Mcardle, J. J. (2013). Race, poverty and SAT scores: Modeling the influences of family income on black and white high school students’ SAT performance. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 115(4), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811311500406

EdTech Staff. (2021). The checklist: Bridging the digital literacy gap. EdTech Magazine. https://edtechmagazine.com/higher/article/2021/03/checklist-bridging-digital-literacy-gap

Eubanks, V. (2011). Digital dead end: Fighting for social justice in the information age. The MIT Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). Continuum.

Gilliard, C. & Culik, H. (2016). Filtering content is often done with good intent, but filtering can also create equity and privacy issues. Common Sense Education. https://www.commonsense.org/education/articles/digital-redlining-access-and-privacy

Giroux, H. (2010). Rethinking education as the practice of freedom, Paulo Freire and the promise of critical pedagogy. Policy Futures in Education, 8(6), 715-721. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2304/pfie.2010.8.6.715

Hockly, N., Dudeney, G. & Pegrum, M. (2014). Digital literacies. Routledge.

hooks, bell. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Lai, J. & Widmar, N. O. (2021). Revisiting the digital divide in the COVID‐19 era. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43(1), 458–464. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13104

Mooney, T. (2018). Why we say “opportunity gap” instead of “achievement gap.” Teach for America. https://www.teachforamerica.org/one-day/top-issues/why-we-say-opportunity-gap-instead-of-achievement-gap

Morris, Sean Michael. (2018a). Courses, composition, hybridity. In Sean Michael Morris & J. Stommel (Eds.), An urgency of teachers. Hybrid Pedagogy.

Morris, Sean Michael. (2018b). Critical instructional design. In Sean Michael Morris & J. Stommel (Eds.), An urgency of teachers. Hybrid Pedagogy.

Morris, Sean Michael & Stommel, J. (2018). The discussion forum is dead; Long live the discussion forum. In Sean Michael Morris & J. Stommel (Eds.), An urgency of teachers. Hybrid Pedagogy.

Noble, S. U. (2016). A future for Intersectional black feminist technology studies. The Scholar & Feminist Online, 13.3-14.1. https://sfonline.barnard.edu/traversing-technologies/safiya-umoja-noble-a-future-for-intersectional-black-feminist-technology-studies/0/

Pendakur, S. L. (2016). Empowerment agents: Developing staff and faculty to support students at the margins. In S. R. Harper & V. Pendakur (Eds.), Closing the Opportunity Gap: Identity-Conscious Strategies for Retention and Student Success. Stylus Publishing.

Rich, M., Cox, A. & Bloch, M. (2016, April 29). Money, race and success: How your school district compares. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/04/29/upshot/money-race-and-success-how-your-school-district-compares.html

Richars, E., Aspergen, E. & Mansfield, and E. (2021, February 4). A year into the pandemic, thousands of students still can’t get reliable WiFi for school. The digital divide remains worse than ever. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2021/02/04/covid-online-school-broadband-internet-laptops/3930744001/

Selyukh, A. (2016, February 6). How limited internet access can subtract from kids’ education. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/02/06/465587073/how-limited-internet-access-can-subtract-from-kids-education

Skinner, Benjamin, Hazel Levy, and Taylor Burtch. (2021). Digital redlining: the relevance of 20th century housing policy to 21st century broadband access and education. (EdWorkingPaper: 21-471). https://doi.org/10.26300/q9av-9c93

Stanton, L. (2017). NDIA, CYC accuse AT&T of “digital redlining” in low-income cleveland neighborhoods (Telecommunications Reports).

Zumbrun, J. (2014, October 7). SAT scores and income inequality: how wealthier kids rank higher. The Wall Street Journal.

- The authors proceed to note that “While some racial/ethnic groups and those with higher household incomes have greater broadband access overall, we find that otherwise demographically similar persons with the same ISP options may nevertheless have different likelihoods of in-home broadband access due to neighborhood characteristics that are correlated with New Deal-era housing policy,” and that, “As our results show, even persons from the same racial, ethnic, or income group had different likelihoods of broadband access in connection with the historical rating of their neighborhood,” 25, 27. ↵

- For early analysis of those trends, see Emma Dorn, Bryan Hancock, Jimmy Sarakatsannis, and Ellen Viruleg, “COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: The hurt could last a lifetime,” June 1, 2020. ↵

- The Netflix example comes from my own anecdotal experiences in and out of the classroom. ↵

- For an example of an institutionally required faculty training, see Craig Guillot, "Bridging the Technology Gap in Higher Ed," March 10, 2021. ↵

- See Noble, Algorithms of Oppression, as well as Sarah Berry, “Your Complete List of 200+ SEO Ranking Factors,” WebFX (June 2, 2021), https://www.webfx.com/blog/internet/seo-ranking-factors/ ↵