8 Sharing Instructional Design

Collaboration and community with the past, present, and future

Mary Klann; Logan Gorkov; and Rossel-Joyce Garcia

Author Introductions

We collaborated on the writing of this piece, but have also maintained our own distinct voices in the notes. Throughout the piece, readers will find footnotes labeled with our names to indicate authorship. These notes are a nod to the social annotation that was a large part of the course we’ll discuss in detail in the article below.

Mary Klann: I am an adjunct professor of history at UC San Diego, San Diego Miramar College, and Cuyamaca College. I received my PhD in US History from UCSD in 2017. My research and teaching interests include Native American History, Women’s History, and Digital History. I love teaching, especially teaching online.

Logan Gorkov: I graduated from UC San Diego in Spring of 2021 with a Bachelor of Arts in History and Studio Arts. My research interests include Indigenous History, LGBTQ+ History, and decolonization movements. I have a love-hate relationship with academia, but I do believe that everyone should have access to and control over their own education.

Rossel-Joyce Garcia: I am a class of 2021 graduate from UC San Diego, where I received degrees in Ethnic Studies (B.A) and History (B.A.) My research interest is K-12 education in the United States, focusing primarily on the entanglements of neoliberalism, race, ethnicity, and class in education.

Introduction

In the article that follows, we make an argument for sharing the responsibility of instructional design with all members of the classroom. Our case study is our class, Digital History and Memory, (nicknamed “DigHist”) which took place at University of California, San Diego from January 2021-March 2021. Throughout the course we learned about the power of collaboration and community building between all members of the classroom in shaping course design and outcomes.

Our DigHist course set out to explore the relationship between digital technology and historical research, writing, and memory. During the first four weeks of the 10-week quarter, we collaboratively analyzed existing digital history projects, especially those created by university students, such as the Race and Oral History Project at UCSD.[1] For the next six weeks, smaller groups of students analyzed selections from a digitized collection of 21 different student newspapers (a total of 675 digitized items) available from the UCSD Library Digital Collections. We were lucky to receive an introduction to the collection from Heather Smedberg of the UCSD Special Collections and Archives.[2] We ended the course with a collaborative proposal for a future digital history project featuring the student newspaper collection.

Our essay below will explore a few important things about the class structure and modality. There were 32 student participants, and one instructor. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, our class was conducted online and asynchronously. We did not have synchronous meetings, communicating instead using tools for social annotation (Hypothesis), collaborative discussion (Padlet, Google Docs), and peer feedback (sharing in progress work via Padlet and a class WordPress blog). The class assignments were also ungraded. For our course, ungrading was characterized by a combination of instructor and peer feedback and students’ “declarations” of their finished work. After finishing annotations, assignments, and/or providing feedback to peers, students submitted their declarations to Canvas, which automatically calculated their point totals.[3] Instructor feedback was still given for assignments, and academic integrity regarding the declarations matching up with the amount of work completed was considered, but the instructor trusted students to make decisions about how they engaged with the course.[4][5][6]

Looking to the Past, Looking to the Future

At the end of our DigHist course in March 2021, students wrote brief letters to future students with advice on how to approach the course. Many of the letters touched upon the value of creativity, exploration, risk-taking, and freedom in the course, with specific mentions of the ungrading policy, collaborative learning environment, and lack of fixed deadlines. One comment highlighted a particular aspect of the course’s design: “Take advantage of the ‘structurelessness’ of the class and learn all that you can!” The class wasn’t unstructured in the sense that students had complete autonomy over the subject of the digital history project (the sources we used were part of a specific digitized collection), but in many important ways it was “structureless.”[7] Primarily, we didn’t set out to end with a completed digital resource. We would end with a proposal that could be taken up, edited and revised, even rejected, by future students. Looking back, the open-ended “work-in-progress” design of the course might have helped to establish unexpected layers of community.

The first layer of community was our class, the 33 participants, including the instructor, who shared reflections and analysis of existing digital history resources, examined the primary sources, and built the final proposal. We will go in-depth on this topic in later sections of this article, but it is worth mentioning that this was not a typical classroom where private work was submitted by students for private feedback from the instructor. Every aspect of the course was open to collaboration, and the weight of instructor feedback was not necessarily greater than that of fellow students. Everyone brought a unique perspective based on the individual research done, and connections were made organically between different students’ work and how it might fit into the bigger picture.

The second layer was the greater UCSD campus history and community, as the primary sources, student newspapers, prompted many participants to look critically at our own experiences on campus, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and learning together in digital space. The community we formed was with each other, but also with the students of the past, who shared many of the same traditions, protests and fights with administration, global awareness, and desire to change the campus for the better. In their final reflection, one student wrote, “I learned so much about UCSD’s past from reading through the newspapers, and I had no idea that UCSD had so many student publications and editorials in the past!” The same student emphasized the value of examining digital history (which, as our class found, could mean anything from the methods used to store and catalog the sources to the ways that visitors interacted with those sources), especially because “we are living in the age of technology.” COVID-19 only made our experiences of the “age of technology” more acute.[8]

The last layer was more future-oriented. Since we designed something that was meant to be implemented, revised, and edited by future students, we were communicating with groups who we hadn’t yet met, who would be experiencing the course in a different political and social moment in time. Additionally, many students asked for ways to follow up with the project, to engage in the future as a participant. Many of us looked towards the future (either as instructor, student, or alumni) with a desire to see how the project progressed.[9]

Ungrading: An Opportunity for Growth and Discovering Genuine Interest

Ungrading in this course was significant to the experience.[10] Ungrading especially contributed to community building, because there was no competition involved. Students collaborated without the worry of a group project where the grade depends on if everyone does their fair share, but also without the pressure of having to do the entire project right on the first go. Students were able to take risks and still gain valuable feedback, rather than get the grade but gain very little growth.[11] In their letters to future students, one student connected ungrading to the creative process: “you can take risks knowing that you will be academically safe even if you later decide it wasn’t the right direction!”[12] The safe route was not necessary, and in this class where the students depended on each other as much or more than they did on the instructor, there was always available feedback in the path to a project proposal rather than the judgment of worth that comes with a grade.

Another aspect of ungrading in the success of our project proposal—and hopefully future project[13]—was the element of being able to pursue information based on the group’s interests. We worked from a set primary source base, the student newspapers. But, the class chose which specific issues to focus on within that set of primary sources. It is unlikely we would have seen the same impact if the overarching project theme had been unilaterally “assigned” by the professor. The project itself remains open-ended for future groups of students depending on the sources that interest them the most. In this sense, ungrading represented freedom for each student to fully devote their research time to elements of the sources that interested them. The letters to future students reflect this. One student wrote that ungrading “made doing the work of reading and engaging with [the student newspapers] much more enjoyable and I was able to put them into conversation with things I already knew and had concurrently been learning in other classes.” Students were drawn to the sources they had connections to, where they felt they had something important to add, and that made the final proposal all the more meaningful and compelling.

Understanding Digital Literacy/History in the Context of COVID-19

As we reflected on the course and began to write this piece, a question emerged about the context of COVID and its impact on our instructional design: Is this a class that could have been taught the way it was or been as successful as it was if it weren’t for the approximately 9 months of practice we already had learning online?

This question has a different answer depending on each individual participant’s perspective. One of the first questions we considered as a class was what was digital literacy? If we are able to navigate the internet with ease, are we digitally literate? Some students asserted that they were, as one annotated in the margins of the American Historical Association’s definition of digital literacy (American Historical Association, n.d.): “I definitely would consider myself digitally literate, especially in the last year when practically my whole life has been based on online meetings, assignments, and maintaining friendships remotely.” However, others expressed fear and trepidation around the idea of “digital literacy,” and still others acknowledged there were some areas of the internet and certain tools that they continued to learn more about. Multiple students also noted that they might assume a level of digital literacy because “a lot of us grew up using technology everyday,” and many “often assume since they grew up with technology, that they know absolutely everything about it.”

Regardless of where students fell on the scale of digital literacy, the reality was that most, if not all, students surely had some experiences with technology over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, as classes shifted to remote learning. As a result, there seemed to be more of an organic use of the digital space in this class compared to a pre-pandemic in-person class that used the same digital tools.[14] In the latter, students may have never had to worry much about digital literacy and may also have had ample opportunity to learn and engage with class material outside of digital spaces, such as in the physical classroom. However, in this class, students were required to step into these digital spaces alone, just as they had been required to in the previous nine months. Since this class was only offered online, unlike a class offered in-person, there were no alternative spaces of learning. If students desired to partake in the class, whether it be because they needed the class for a general education requirement or because they genuinely wanted to learn about digital history, there was really no other option but to step into the online “classroom.”[15] The product of these circumstances was a class of students that seemed to embrace (some fully willing, some reluctant, and some in-between) the digital nature of the class.[16][17]

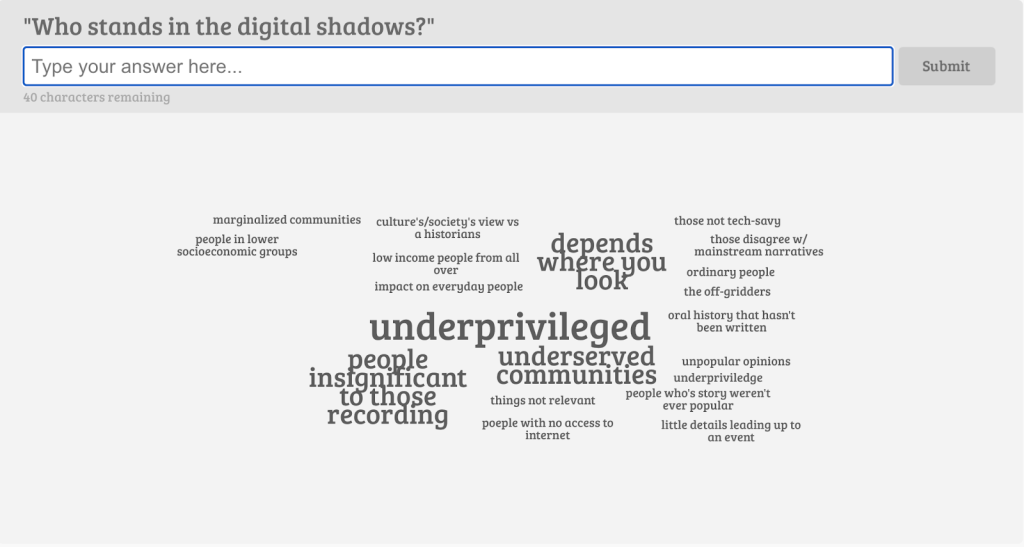

However, as we worked out during the first few weeks of the course, access to digital literacy and engagement with digitized archives of historical material is contingent on the social, cultural, racial, and/or economic spaces we occupy. In her 2016 article in the American Historical Review, historian Lara Putnam, questioning the tendency of more and more historians to engage with digitized primary sources, wrote, “There is a real world out there. The totality of sentences that have ended up in print in no way corresponds to the proportions of past human life. Who stands in the digital shadows (Putnam, 2016)?” The class generated a revealing word cloud[18] in response to Putnam’s question, highlighting the role of the historian/researcher in framing what is relevant and important, and the ways that class, race, and/or gender identity impact how historical actors’ experiences are remembered and recorded.

As a whole, the annotations of our readings in the first three weeks of the course revealed our willingness to critically engage with all the contradictions of digital history, questioning how digital sources and tools shaped our learning, and the processes of preserving and analyzing diverse histories. In an opinion-based poll we answered during our second week, the class was given a choice of two options.[19] Did digital history have more potential to expose and document voices from underserved and underheard communities? Or, did it have more potential to leave certain historical actors in the “digital shadows”? The results were revealing: 80% of respondents voted for the first option, that the benefits outweighed the potential pitfalls of digital history. However, many people were torn. One student elaborated, “I think I am more pessimistic when it comes to digital history just because in the last year, I have seen so much of the news focused on the wrong aspects of events, ignoring the bigger picture that would have resulted from genuinely knowing the opinions of those in the ‘digital shadows.’” Issues of equal internet access and other lived experiences made this question especially thorny. Other students explained that “If the community is criminally under-heard there’s a lot of good-intentioned people willing to use the internet to help make their voices heard;” and “many people have found community through the internet due to not being able to find it where they live in real life (whether it be due to location, lack of representation, etc.).”

The question of the role and potential of digital history for exposing and documenting underheard communities is even further complicated by the ways in which social science research has often been violent and extractive in these communities. Western academia has long upheld a dichotomy of researcher and subject, where the researcher is the primary producer of knowledge about the subject and the primary benefactor of the produced knowledge. In this understanding, the researcher holds the power—and the institutional means—to decide what will or will not be said about the subject. The possibility of this dichotomy certainly remains in the realm of digital history (and it is up to us as researchers to wrestle with what it means to be an ethical researcher), but at the same time, the possibility to depart from it arises. With the internet, and the practice of digital history, it is possible for ordinary people[20] to assume the role of knowledge producer through creating and sharing digital content. In this model, ordinary people, who may have otherwise been the subject about which knowledge was produced, decide how they want to be known without the same level of institutional barriers they might come across at, for example, the university. However, this model assumes that all ordinary people have access to the digital world, which is not the reality. Even if people do have access to the digital world, the question might then shift to who will be listened to. Websites like Wikipedia where anyone can add or remove information have long been discredited by academics.[21][22] What does it mean for these kinds of websites to be discredited when these websites are where ordinary people go to share digital knowledge (Rosenzweig, 2006)? This concept can even be applied to our digital history class, in which one participant was a professor of the university and the other 32 were all students enrolled in the university. Is our project worth looking at simply because it was constructed and executed within the parameters of UCSD? Would it still be worth looking at if it was done outside of the university or outside of any other research institution?[23]

It was worth digging into these complicated issues before we started building our own digital history resource. Without understanding the methodological and practical complexities of digital history, we wouldn’t have been able to fully engage with the digitized primary sources we worked with in the second half of the class. Discussing some of the theoretical questions behind digital history helped us to understand what was behind the choices we made in our final proposal. It also helped to critically engage with other aspects of our lives that we lived online, which, during this time, was practically all of it. Moreover, discussing issues of access to digital archives and whose voices are remembered and preserved prompted us to think more critically about access to digital technology in the online classroom, and how we envisioned making our proposed digital history resource accessible.

Building a Humanized Online Classroom

In their letter to future DigHist students, one student wrote:

“I think one thing that is encouraged a lot in this class is collaboration. We have to read over each other’s work and posts all the time. Personally I think this is pretty helpful, it lets me see what’s interesting to other people as well as what the common themes in what we’re studying are. I think the purpose of digital history is all about communicating experiences and viewpoints.”

The elements of instructional design that this student highlighted—collaborative reading, peer feedback, working together to identify common themes—corresponded well with their view of the subject matter of the course, digital history. During the first few weeks of the course, we analyzed and critiqued a selection of existing digital history projects, interrogating digital history methods such as tagging and non-linear pathways of reading. As a group, we collaboratively annotated different digital history sites using Hypothesis. Additionally, the instructor posed questions in the annotations to be answered via poll or word cloud. Students then checked in on a weekly Padlet where they could see the results of the polls and word clouds and offer their thoughts on the conversation as it evolved. As we discussed digital methods together, we established the basic goals for our own digital history resource: collaboration, frequent feedback, and consideration of the widest possible audience.

The course was heavily collaborative, but also prompted each individual to independently engage with the material, drawing out their own research interests. In addition to social annotation, students each conducted individual research on a set of student newspapers and shared that research through in-progress “project journals,” documents shared through Padlet, and as shorter posts on the course’s WordPress blog. As another student wrote in their letter:

“Focus on what you find interesting when doing research. Be selective with your time and what you want to look for. There is a lot of information that you are going to have to look through and it makes it so much easier to be selective on what you want to look at. This class does a good job about giving you that freedom, but it also forces you to choose. Be selective; pick the things that are interesting to you.”

Providing opportunities for individual choice and autonomy were critical, not antithetical, to the success of a heavily collaborative class. An excerpt from another letter to future students explains why: “You will be surprised your other classmates will be responsive and helpful! Be organized, provide pictures, and show your thoughts from your writing! Let them hear your voice!”

This student, as well as many other students in the class, boldly voiced their thoughts through their own work, but also in response to their classmates. One reason for this may have been that the considerably flexible timetable of the class (with the primary restriction being the quarter system) allowed students the time to process and edit their thoughts at their own pace. Once students formed their thoughts, they could share them with the class when they were ready as opposed to having to read something, immediately respond on a discussion board, and then continue the discussion in class the next day, all before they had a chance to fully absorb the material. Another reason students may have so willingly shared their thoughts is simply because they had the space to. Unlike a class taught in-person where they might have to compete to speak with a more outspoken student or where they might be sitting in the back of a 300-student lecture hall (out of reach from the professor), our online “classroom” offered students virtually unlimited space to share their thoughts freely, as they pleased.[24]

Something very specific to the internet may also have encouraged people to express themselves: the sense of anonymity. Though we tend to think of online anonymity as a bad thing, as something that enables some to discriminate against others in public without repercussion, anonymity provided a sense of safety in our course. As mentioned, there was no fear of having to compete with the more outspoken student, because everyone began on a relatively level playing field in digital space. We were, of course, not completely anonymous.[25] We knew each other’s full names, which isn’t nearly as likely in an in-person class, but there is something to be said about posting something to the discussion board while alone in your own space versus feeling the 300 pairs of eyes turn towards you answering a question in a large lecture hall. We maintained the professionalism expected in the classroom, but the feedback went far beyond the expectations of “post once, reply twice” discussion methods.[26][27]

Would this course design work as well in a face-to-face classroom? Is online pedagogy critical to this course’s design? In order to fully answer this question, we need to return to Putnam’s conception of the “digital shadows,” and our critical engagement with the idea of how digitally “literate” each class participant is. In many ways, this question can’t be answered without fully understanding the context of COVID-19 and each participant’s (whether student or instructor) experience with remote teaching and learning.

Issues of access during the pandemic became very prevalent—and although things like laptops could be supplied temporarily by the school, a stable internet connection and a nearby timezone could not. Having no live portions to this class made it much more possible for everyone to fully participate, rather than having recordings of discussions that could be watched, but could hardly be added to in a meaningful way. For the full 10 weeks, students had access to every piece of work (not including declarations and personal reflections) created by other students. A student could post at any hour, and their voice would still matter and be a part of the discussion—there was never a point at which the discussions were “over” until the quarter was over.[28]

It is essential to consider how and why relationships are built and sustained, regardless of the modality. Some elements of the course design—for example, an unfinished final product, and ungrading—could be applied to either a fully online or fully in-person course, or something in between. For our class, which occurred in the context of COVID-19, the asynchronous online modality facilitated essential elements that helped make the class successful: collaboration, feedback, and individual agency.

A critical question we asked was how did we build a cohesive project without ever having a face-to-face or live online meeting? Many of the points already brought up speak to this, such as the space and time to boldly voice thoughts. Although students worked individually on assignments, they also had time to read and respond to what others had written. Students built on the feedback given by other students and the instructor, and the feedback they provided to others. A strong sense of communal tone was acquired, whether we were aware of it or not, and then continued to build. There was also time to absorb the feedback received and incorporate it into the next assignment, where the process started again, establishing trust in the students that is not typical for project-based classes.[29] Students could depend on each other, rather than immediately going to the professor when they were feeling stuck.[30]

Building Community through Historical Student Newspapers

We never met face-to-face and had only one optional online meeting in our course. However, there was a valuable sense of community that grew over the course of the ten-week quarter. One of the ways that we built that community was through collaborative analysis of the digitized collection of historical UCSD student newspapers. Students kept “project journals” reflecting on a set of chosen newspapers, which they turned into the class twice during the quarter. Students also posted to our WordPress blog with essays about specific themes and issues that arose from the newspapers and posted to “thematic reflection” Padlets with ideas for our future digital history project, including format, purpose, and, as a repeat theme within digital history, access.

One theme that emerged from the analysis of student newspapers was campus traditions and community activities, many of which are still practiced on campus today. Many students read issues of Revellations, a student publication created “by the students and for the students of Revelle College,” one of UCSD’s seven colleges, between the mid-1970s and mid-1990s. The campus traditions described in the issues of Revellations from the 1980s and 1990s sparked thoughts about the power of nostalgia and community, especially in the context of COVID-19, when so many of us were away from campus. Final course reflections also touched on the significance of examining campus traditions through the newspapers. One student reflected, “Traditions are so important towards preserving a campus community. Maintaining those events are crucial to involving other students and giving them an opportunity they really wouldn’t get anywhere else.” They ended their reflection with a message for future students: “Get involved, participate, protest, do everything you can to be an active member of your Triton community.”

As we thought about the best way to showcase the student newspapers in a future digital history project, members of the class expressed their sense of belonging in the UCSD community, something they shared with both the authors of the student newspapers and future visitors to the project. Reading, analyzing, and thinking through ways to showcase the student newspapers in a future digital history project encouraged students to think of themselves as both current UCSD students and future alumni.[31] In their final course reflection, one student wrote, “Learning about…the student newspapers was awesome. I wish I’d known about them sooner because there are a lot of past insights held within them. I think it is also very cool that not only do you get to learn about history, but you get to do it from an alumni’s perspective and it kind of hits home harder.” Another student reflected, “I learned that our campus has a long history of students writing newspapers, and am glad to be a part of the reason why the tradition will continue.”[32] In these quotes, there is both a reference to the past and a look towards the future, as students thought through ways to make these digitized items more accessible for other students and alumni to interact with them. In our final proposal, students suggested tools that would change the visitor experience of reading a static PDF to interacting with the newspapers, including timelines, polls, links to current campus resources, comments, and ways to submit suggestions for newspaper articles to add.

Similarities in the issues that were raised in historical student newspapers prompted students to both discover and reflect on the continuation of those issues today. For example, radical student groups of the 1970s voiced discontent over the disconnect between administration and students (UCSD Student Newspapers, 1972a, 1972b, 1973). In a comment on one of Logan’s posts, one student noted that this “is still an issue that goes on at UCSD today with many of the organizations on campus.” Rossel’s analysis of the relationship between research on campus and the Department of Defense covered in one campus newspaper, The Indicator, taught other students about this long-standing connection (UCSD Student Newspapers, 1968). “I never fully understood how intertwined they were,” one student commented. “I feel as if just as many students don’t fully recognize the history of our campus.” Another comment on Rossel’s analysis read, “It’s not something that gets a lot of mainstream attention despite how many students would probably be upset about it.”[33]

In addition to the “letters to future students,” we ended our proposal with a list of questions for past students who had worked on the newspapers, in the hopes of one day coordinating with alumni when the project is ready to launch. Many of those questions asked alumni to reflect on their experience of the UCSD campus community. For example, “Do you feel you made a truly significant contribution to either the campus or society in general during your time at UCSD?”; “Do you think UCSD has responded appropriately to the demands you’ve made in the past?”; and “Since we found your writings so interesting for the time period, did you ever feel that way when looking back at those before you?” Since the newspapers were vehicles for former students’ expressions of political protest, identity formation, and campus traditions, reading and analyzing them allowed DigHist students to engage with alumni as both historical actors and members of the broader university community.

There was something significant about how analyzing the ways in which the experiences of past UCSD students opened up opportunities for current students to discuss their relationship to the campus community. One student wrote an analysis of a series of issues of Revellations from the late 1980s-mid 1990s where they engaged with one of UCSD’s more unfortunate nicknames, “UC Socially Dead.” In an article from the October 8, 1990 issue of the student publication, then-freshman student Jack Sharp wrote about the three “personalities” found among UCSD students: the “Tensies,” whose “stress levels reach stratospheric heights every day,” causing “any bio-feedback machine within miles,” to “suddenly and inexplicably explode;” the “Partimaniacs,” who “attempt to fit their classes in between parties and hangovers;” and finally the “Stressies,” who could be “typically described as blurry streaks of panic running through the Plaza (USCD Student Newspapers, 1990).” These classifications resonated with other DigHist students.[34] In their writing about Sharp’s article, the student author noted, “After scrolling through the UCSD SubReddit every day for the past two years, it seems like almost everyone would be categorized into Tensies or Stressies, with so many posts highlighting a noticeable decline in mental health, social interaction, and connection to the campus community while attending college here.” However, instead of focusing on stress and tension as the main takeaways from the past, they also urged other students to reconnect with campus traditions and other students. Instead of “UC Socially Dead,” we should be “UC Socially Determined.” One student commented, “I found your post not only inspiring and motivating, but it gets me so excited to be back on campus!” Another wrote, “Reading your post made me excited to go back to school and take advantage of the opportunities presented!” Reading about past students’ experiences allowed current students to reflect on their own.[35][36] The digital format of both the DigHist course and the collection of student newspapers lent itself to this kind of reflection, as class members visited and revisited the historical sources and the feedback of their peers asynchronously. It was easy to see how some of the tools and methods our class used to collaborate and maintain connection could be employed in a future digital history project.

Sharing Instructional Design

During the COVID-19 turn to remote learning, everyone, including students, took on the challenge of instructional design. The “structurelessness” of the DigHist course encouraged students (and the instructor) to be intentional about how—and why—each participant interacted with the material and with others in the class. This kind of agency can be uncomfortable and challenging and demands that all participants—including the instructor!—take risks.

In the mid-quarter reflections (seen only by the instructor and individual student), students provided positive feedback about ungrading and flexible deadlines, emphasizing how learners were able to “take charge of knowledge,” in this class. However, there was also plenty of “digital discomfort” in the early reflections. As Kristin Allukian, Allison Duque, and Alexander Cendrowski wrote in their article on digital discomfort within the Suffrage Postcard Project, “The pedagogical framework of the project asks team members, through digital decentering, to challenge their willingness to invest in the research field, methodology, and co-researchers; to challenge power structures and dynamics inherent to almost any project; and perhaps most importantly, to challenge their sense of intellectual autonomy (or lack thereof)” (Allukian et al., 2020).[37] The digital discomfort that surfaced in the mid-quarter reflections related to the open-endedness of the final project, unfamiliarity with some of the tools that were new to some (Hypothesis, WordPress, and Padlet), and uncertainty with the flexibility of course deadlines. In other words, discomfort can arise when learners have more control over their own learning.[38] In response to the reflections, the instructor adjusted some of the formatting for distributing feedback, including creating places (a Google Jamboard and a Padlet) for feedback that applied to the collective work of the class, rather than for individual students. Sharing collective feedback was done intentionally as a way to reinforce the value of sharing in-progress work, but also as a way of transparently communicating how feedback was developed.[39]

Decentering traditional classroom power dynamics by encouraging collaboration, sharing work in progress, ungrading, and embracing a final project that wasn’t fully defined, helped to make the class more meaningful for all involved. The main idea behind the course was simply to generate ideas. There were no rules completely set in stone. The only things students were given for certain were the digitized archive of student newspapers and the use of the WordPress blog, Hypothesis annotations, and shared online discussion spaces. Understandably, that amount of freedom can be extremely disconcerting because the course was unlike many others students had previously taken. We were working towards a goal that we set, as a class, not one that had been set in advance by the instructor, the department, or the university. In one student’s final reflection, they wrote, “I was hesitant to learn something new at first, but I am glad I did. This class was a lot of fun, especially learning while being an active participant.” Sharing power was intentional instructional design, something that requires time for everyone to feel comfortable taking risks and establishing trust between participants. That trust turned into genuine interest and care about the direction of the project. Several students asked in their final reflections, despite the end of the class, “How can we keep track of this project?”

A course can not be fully “designed” before it begins. Every set of students has different needs and goals for their classes. Instructors (and instructional designers) need to take those needs and goals into account, sharing the responsibilities and power of course design between instructors, students, and staff (including archivists and librarians) before and during the course. If we want to hold students accountable for pursuing their education, then we also need to trust their input and form a collaborative learning structure beneficial to students first.

References

Allukian, K., Duque, A. & Cendrowski, A. (2020). Decentering digital discomfort. Hybrid Pedagogy. https://hybridpedagogy.org/digital-discomfort/

Association, A. H. (n.d.). The career diversity five skills: Digital literacy. https://www.historians.org/jobs-and-professional-development/career-resources/five-skills/digital-literacy

Putnam, L. (2016). The transnational and the text-searchable: Digitized sources and the shadows they cast. The American Historical Review, 121(2), 377–402. https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/121.2.377

Rosenzweig, R. (2006). Can history be open source? Wikipedia and the future of the past. Journal of American History, 93(1), 117–146. https://doi.org/10.2307/4486062

UCSD Student Newspapers. (1968). The Indicator. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego. https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb11956213

UCSD Student Newspapers. (1972a). Black Voices. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego. https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb55983863

UCSD Student Newspapers. (1972b). Lumumba Zapata. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego. https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb2905731p

UCSD Student Newspapers. (1973). Nine. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego. https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb8635959n

UCSD Student Newspapers. (1990). Revellations. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego. https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb90113897

- The Race and Oral History Project is the result of the oral history research conducted by members of UCSD’s Race and Oral History in San Diego course. Students in the course worked with community partners, organizations devoted to themes such as migration, settler colonialism, and militarism to document the history of race in San Diego. ↵

- Mary Klann (MK): Heather Smedberg, Harold Colson, and Cristela Garcia-Spitz at the UCSD Library provided essential guidance and support before the class started and as the course progressed. ↵

- MK: Credit for the language and format for “declarations” goes to Laura Gibbs, former online educator at University of Oklahoma, who has generously shared many ideas with me this past year. ↵

- Rossel-Joyce Garcia (RJG): This was the first ungraded class I have experienced. Despite students not being graded, the participation levels in this class were similar, if not greater than, participation levels in the other classes I’ve taken at UCSD. ↵

- Logan Gorkov (LG): Other professors I had encountered online during the pandemic have also taken a more "hands off" approach, where there were little or no synchronous lectures. However, one such professor gave no instruction novel to the course, he instead used pre-pandemic recordings of the class, where discussion between the professor and students could not be heard (apart from the professor's contextless answer). Feedback given on assignments was minimal—I received a total of 7 words between the midterm and final papers, and that is the extent of my interaction with that professor. ↵

- MK: I started ungrading all of the courses I teach (at UCSD and other colleges) in Fall 2020. The quality of students’ work and effort has been the same, if not better, than courses I have taught with traditional grading methods. I’m never going back to traditional grading. ↵

- MK: Before the course began, I envisioned ending our quarter with a finished digital project. It was only after talking to the archivists and librarians at UCSD that I fully understood the magnitude of all that would entail. I decided to adopt a more open-ended approach to the “end” of the course. Our final project was defined further as the quarter progressed, and we began to identify key themes as a group. The class contributed to a shared Google document where everyone contributed answers to questions that had been generated over the course of the quarter. I am teaching the course again in Spring 2022, and the new group of students and I will build off this Google document. ↵

- MK: I had already been trained to teach online pre-COVID, through training provided by the San Diego Community College District. I love teaching online. However, I knew that many students in the course had not taken online courses outside of remote learning during COVID and did not have the same feelings about online learning. I found all the learners in this class to be incredibly willing to critique and engage with digital technology and how it shapes historical research. ↵

- LG: This was the first time I was interested in continuing to hear about a project after my time in a particular class ended. If I hadn't actively participated in classes, I would know the blame for that was on me, but this is the first and only time during my academic career where I felt like I was doing something that made an impact on a future other than my own! ↵

- MK: I owe my understanding of ungrading to several educators who have written about their methodologies, especially (but not limited to): Gibbs, L. (March 15, 2019). Getting rid of grades. OU Digital Teaching. http://oudigitools.blogspot.com/2019/03/getting-rid-of-grades-book-chapter.html; Kohn, A. (2018). Punished by rewards: The trouble with gold stars, incentive plans, A’s, praise, and other bribes (25th Anniversary Edition). Mariner Book.; Sackstein, S. (2020). Shifting the grading mindset. In S. Blum (Ed.) Ungrading: Why rating students undermines learning (and what to do instead) (pp. 74-81). West Virginia University Press.; and Stommel, J. (March 11, 2018). How to ungrade. https://www.jessestommel.com/how-to-ungrade/. ↵

- LG: In college, I personally became so obsessed with grades that if finals were available to be picked up after grading I never went out of my way to do it. The grade I got in the class was all that mattered, and I could already see that online. Improvement didn’t matter—and it did not feel like improvement was valued between courses regardless. Every professor has such distinct expectations that frequently do not even line up with what is taught in the required core writing courses. A paper was not about becoming an active participant in my learning and research, but to say what a professor wanted to hear. That isn’t to say I never looked at feedback—but the majority of feedback I received from professors (or their graders) was so baffling that I only learned how to write my next paper for that same person. I truly feel like I built on a unique writing skill here, not because I was writing to please Mary Klann, and not because I was writing another discussion board post, but because of the novel method of the blog posts and genuine care into this project—and us as students, having potential to Make (with a capital “M”) something that mattered, not just demonstrate what we have learned, or rather, how we have learned to appeal to a professor. ↵

- RJG: One of my biggest takeaways from the DigHist class was finding what my non-essay writing voice sounded like, and one of the primary reasons I was able to do that is because of the ungrading policy. I had the freedom to play around with my writing without worrying about what would happen to my grade! In the end, I had written some things that I didn't really like, but I also wrote some things that I absolutely loved, and in the process, I learned a lot about my writing style. ↵

- MK: Our class was listed as a “special topics” class in US History. As an adjunct, my employment at UCSD and the other colleges where I teach is precarious. However, I hope to someday offer this course as a permanent course with its own course number, so future students (and alumni) may participate in this project. My goal is to continue to offer the course (at least partially) online. ↵

- RJG: In the majority of classes I took pre-pandemic, the primary digital platform used was Canvas. One of the most common uses of the platform was for students to create original discussion posts and respond to other students’ posts. In my experience, this use of the platform has often resulted in bare-minimum discussion posts and responses that felt forced. Even if students got little to nothing out of it, they were able to depend on future in-person classes to interact with the material. ↵

- MK: As an instructor, this tension is something I really tried to keep in mind as the course progressed. My goal with this course (and with all the courses I teach) is to try to cultivate a space for joy in learning, whatever that may look like for each student. ↵

- RJG: I was one of the students who was quite willing to embrace this! One of the things I missed most when switching to online learning is the in-person discussions that were common in many history classes at UCSD. Since there was no way for me to get this face-to-face interaction in class during the pandemic, especially because our class was completely asynchronous, I was eager to accept the digital “classroom” and whatever opportunities it had for interaction with my classmates. ↵

- LG: I was in-between initially. I had taken face-to-face classes with Professor Klann before, and so I was familiar with her digital tools, but hadn’t really experienced them as a primary method of communicating with others. Despite having been in 9 months of online classes already, I had yet to experience a sense of community in my classes (even those that did have live meetings), and so I came in skeptical. However, by the time we got to working on the student newspapers, I was excited to see feedback from my classmates in a way that I hadn’t experienced before. ↵

- For this class, word cloud questions were administered via Answer Garden, a free word cloud generator. https://answergarden.ch/. ↵

- In this class, opinion-based poll questions were administered via Slido. https://www.sli.do/. ↵

- "Ordinary people" is used to refer to people outside of research institutions. ↵

- RJG: I remember until my sophomore year of college, teachers have told me to avoid using websites that end in .com and .org when sorting through the internet. I was always told to use Google Scholar or websites that ended in .edu, as they were thought to be more credible. ↵

- LG: There are so many instructors out there that are still afraid of internet resources (like Wikipedia) rather than teaching us how to critically engage with them. The conversation never seems to go beyond “not everything on the internet is true.” ↵

- LG: Here’s my personal struggle with academia—I want to do research, and I want to be “qualified” to do research, but I don’t see academia as a place to do that without being extremely, impossibly selective about where I go and what structures I buy into. ↵

- MK: To me, peer feedback was an essential part of the course. One of the ways I tried to communicate its significance was by giving ample time for feedback. Students usually had a full week to read and respond to their classmates’ blog posts and project journals, without any extra reading or activities attached to that week. Additionally, the class also contributed to two “Thematic Reflection Padlets” throughout the quarter. These were shared spaces where the group worked together to identify connections and cohesive elements in everyone’s individual research. As the quarter progressed, the themes of the digital project began to emerge in the connections that participants were making with each others’ work. ↵

- MK: There were opportunities for students to be anonymous in certain aspects of the class, namely in the annotations of course readings via Hypothesis. We used Hypothesis outside of our Learning Management System (Canvas), which meant that students could choose their own usernames. Some chose pseudonyms for this format. However, in other aspects of the course, like the WordPress blog, our full names were visible. Our WordPress blog was available through the university, so each participant’s username was linked to their UCSD account. ↵

- LG: This is where the merit of a “post once, reply twice” seems relevant, if only it wasn’t meant to be something that just proved you were alive and paying just enough attention to your online course. But our Padlets asked us to reply to other people and did not necessarily put a limit on it, but I feel like we got good engagement regardless! ↵

- RJG: I think a huge part of this was also that Dr. Klann gave us flexibility in our posts and responses. A big thing for me was that there were no word counts imposed on us, so I was able to focus on the quality of my posts and responses (which sometimes still ended up being quite lengthy). I also loved that we were allowed to respond in GIFs and emojis because it seemed to make things feel a little more personal, like in-person classes, and not robotic. ↵

- MK: And here we are continuing these conversations after the quarter’s end! ↵

- MK: I saw this trust build as the instructor. I also tried my best to communicate my sense of trust in everyone by sharing my feedback about in-progress work openly. Since the course was ungraded, my feedback was never meant to justify why I had subtracted points from a particular assignment. I always tried to frame my feedback around things that stood out to me as exciting or useful for the class discussion and questions that could encourage further thinking about a particular topic. I also left feedback in “public,” responding to annotations, posting to the Padlet, posting comments to the WordPress blog, or creating my own public Padlets or Google Jamboards with my observations about themes that had come up for particular assignments. ↵

- LG: And I personally never felt "stuck" because of the instruction, but rather creatively I wasn't sure where to go next. It was extremely helpful to see what questions were asked of me before and what questions were being asked in general to hone in on what we were doing as a class. And again—I wasn't doing this out of some sense of "oh we want to make sure this is cohesive!" but about following the lines of thought that I found interesting. Sometimes my next post would come out of what I didn't see other students talking about yet. ↵

- LG: It felt like we would be taking the place of the students we were reading about. One day, future students will look at our digital history project, and build on it using the project itself as a primary source. Who knows what that will look like? Will it be alongside student newspapers written today? How will they understand digital literacy and access? It surprised me that this made me feel hopeful to think about myself as a part of UCSD’s past—something for future students to interact with and maybe understand us. It’s a connection with the campus that is not focused on networking and job-finding, but about understanding the moments in history we study. ↵

- RJG: I love that we have this space to document our thoughts! There is space for past, present, and future students (and also anyone who comes across the website) to interact with one another, and I think that’s something unique that you can’t always get outside of the internet. It feels like we are no longer only presenting a one-dimensional history where the past is the past, but it feels like now there is also an ongoing student narrative, where we are all in dialogue with one another in these digital spaces! ↵

- LG: I am not surprised that the typical class at UCSD doesn’t utilize the student newspapers—there's a vested interest in not learning the history of UCSD if it isn't pretty or convenient for the administration to change. All we have left of George Winne Jr. (who self-immolated in protest of the Vietnam War) is a very minimal memorial. New and pretty buildings sell, more resources for marginalized groups do not—even if they’re being begged for. ↵

- MK: As an instructor, the resonance of these categorizations in today’s student population seems like such essential knowledge. I definitely did not assume that all UCSD students were “Partimaniacs,” but I’m not sure how much I would have understood the (enduring) meaning behind “Tensies” and “Stressies” before introducing ungrading into my courses and inviting students to share what they thought about how grades have shaped their educational experiences. As a former UCSD graduate student, I was (and perhaps still am) a “Tensie,” but it was helpful to hear how close to home these labels hit for others. ↵

- LG: I think I became really frustrated with the administration in a way I wasn’t before, with the student newspapers teaching me that the on-campus problems I was already frustrated about were not new, and the administration still chose to do very little about it. I felt more community with those who were angry with the administration, but also, due to being unable to disconnect administration from the university, couldn’t help but wonder what my schooling could have been like had problems from the 70s been solved in the 70s, rather than continuing on for the next generation to deal with. That isn’t to say no progress has been made, but after reading the student newspapers, I’m hesitant to give any credit to the administration. ↵

- RJG: I think that depending on each students’ positionality, the newspapers were received in many different ways. For me personally, as someone who was involved with campus organizations and even part of a department (Ethnic Studies) that was born out of student organizing on our campus and on other university campuses, these newspapers did not necessarily change the way I understood my own experiences as a student. Rather, they pushed me to consider how things have, or haven’t changed, as I related the content of the newspapers to the contemporary moment. It also allowed me to take a step back and question the more technical side of these newspapers. ↵

- The Suffrage Postcard Project can be accessed at https://thesuffragepostcardproject.omeka.net/about. ↵

- RJG: I think that this discomfort also has to do with all the unlearning that had to occur for some students. Based on my experiences, open-ended finals and flexible course deadlines were rare at UCSD, so perhaps a lot of students had to forget (or unlearn) about the structured finals and harsh deadlines that they were so used to. Additionally, the majority of the professors at UCSD opt to use Canvas as the primary digital space for their classes, so I think part of the discomfort also came from branching away from Canvas, which was overly familiar to many students. ↵

- MK: I had found a lot of benefits in sharing feedback for individual assignments in “public” (commenting on Padlet posts) because I could reference students’ peer feedback in my comments and bring others into a larger conversation. But collective feedback also allowed me to share what I was thinking about the work that everyone was contributing to the course through their individual contributions. I also shared the links to the Padlet/Jamboard before I had finished all of my comments. It was feedback, in process, of in-process work. In previous courses, I had purposefully hidden all grades/comments until I had finished responding to everyone. Since the class was ungraded, there was much more flexibility (and much less anxiety) for me in terms of how I distributed feedback. I was also much more excited to read and respond to student work since I wasn’t required to detract any points or assign a letter grade. ↵