In This Chapter

Academic writers use sources as evidence to support the debatable claims that they make. Strong writers know that they need to evaluate the sources they use.

As we’ll discuss later this semester, simply finding sources about your topic won’t be enough for college-level academic writing. Students will need to analyze sources for their relevance, correctness, authority, and appropriateness.

Think about the conversation from the previous chapter about the greatest musical artist of all time. To make your argument, you would want to draw on authoritative sources and real, verifiable facts, rather than, say, what your mom’s friend Quincy told you one time when you were younger. It’s not that Quincy is necessarily wrong. It’s more that the other people in the conversation won’t have any idea who Quincy is or why they should believe him.

But what if Quincy is really legendary producer Quincy Jones? Does that change the validity of your supporting evidence?

What if Quincy is just some guy your mom knows from her days working at the local supermarket in college? Does that change the validity of your supporting evidence?

Hopefully, you said yes to both of those above situations.

Understanding that Quincy Jones is likely a better source to quote than Quincy Smith when it comes to supporting claims about the greatness of a musician means that you already understand an essential part of every argument: meeting the rhetorical situation.

Before we look more closely at how the rhetorical situation can help students be stronger academic writers, let’s first look at what rhetoric is.

What is Rhetoric?

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. In Ancient Greece, Aristotle wrote that rhetoric was the ability to observe and use all of the available means of persuasion for a specific time, place, and purpose.

Whether you’re composing texts to your friends or writing an essay for a history class, you are using writing to communicate. Every time you tap out a text, you are making choices (whether consciously or not) about how you will address your audience to best succeed in whatever purpose you might intend. With each message you send or paper you write, you are engaging in the use of rhetoric.

Think about the conversation about the greatest musician of all time. No matter which artist you pick, you need good supporting evidence. But not all evidence works for all situations. You certainly wouldn’t want to say the first thing you think of. You wouldn’t even want to say the first thing you google.

Depending on the other people in the discussion, you will want to select the evidence that would work best to support your arguments for that audience and in that situation.

For example, if the people in the conversation are all classically trained musicians who are virtuosos on their instruments or who play in the local symphony, it’s likely that an artists popularity and record sales won’t sway them to agree with your argument. You would want to select evidence that carefully aligns with your audience’s values and beliefs. You would probably want to demonstrate your chosen artist’s expertise and talent instead. You might want to cite other classical artists who have said positive things about your chosen artist. If your artist doesn’t play an instrument, you might want to show how rapping or singing is an equally important art form. Your mom’s friend, even if he’s Quincy Jones, might not make an impact on your audience.

Addressing your reasons and evidence to the audience and situation would help you make a successful argument. Doing so means that you are meeting the rhetorical situation.

What is the Rhetorical Situation?

Parts of the Rhetorical Situation

Each instance of communication has the following parts:

- Speaker/Writer: Produces the communication

- Audience: Receives the communication

- Message: Information being communicated

- Purpose: Reason for or goal of the communication

- Context: Specific situation or limitations of the communication

- Exigence: The urgent need for the communication to happen

- Genre: The form the communication takes

The term “rhetorical situation” refers to the circumstances that bring communication–including written texts–into existence. The concept reminds us that writing is a social activity, produced by people in particular situations for particular goals. It helps individuals understand that, because writing is highly situated and responds to specific human needs in a particular time and place, texts should be produced and interpreted with these needs and contexts in mind.

As a writer, thinking carefully about the situations in which you find yourself writing can lead you to produce more meaningful texts that are appropriate for the situation by being responsive to the needs, values, and expectations of your audience. This is true whether writing a workplace e-mail or completing a college writing assignment.

Elements of Any Rhetorical Situation

Speaker/Writer

The writer (also termed the “rhetor”) is the individual, group, or organization who authors a text. Every writer brings a frame of reference to the rhetorical situation that affects how and what they say about a subject. Their frame of reference is influenced by their experiences, values, and needs: race and ethnicity, gender and education, geography and institutional affiliations to name a few.

Audience

The audience includes the individuals the writer engages with the text. Most often there is an intended, or target, audience for the text. Audiences encounter and in some way use the text based on their own experiences, values, and needs that may or may not align with the writer’s.

Message (or Subject)

The subject refers to the issue at hand, the major topics the writer, text, and audience address.

Purpose

The purpose is what the writer and the text aim to do. To think rhetorically about purpose is to think both about what motivated writers to write and what the goals of their texts are. These goals may originate from a personal place, but they are shared when writers engage audiences through writing.

Context & Constraints

The context refers to other direct and indirect social, cultural, geographic, political, and institutional factors that likely influence the writer, text, and audience in a particular situation.

Exigence

The exigence refers to the perceived need for the text, an urgent imperfection a writer identifies and then responds to through writing. To think rhetorically about exigence is to think about what writers and texts respond to through writing. As the previous chapter suggests, however, sometimes the exigence can be interpreted as giving rise to the entire rhetorical situation.

Genre

Often considered a type of constraint, the genre refers to the type or form of text the writer produces. Some texts are more appropriate than others in a given situation, and a writer’s successful use of genre depends on how well they meet, and sometimes challenge, the genre conventions.

Visualizing the Rhetorical Situation

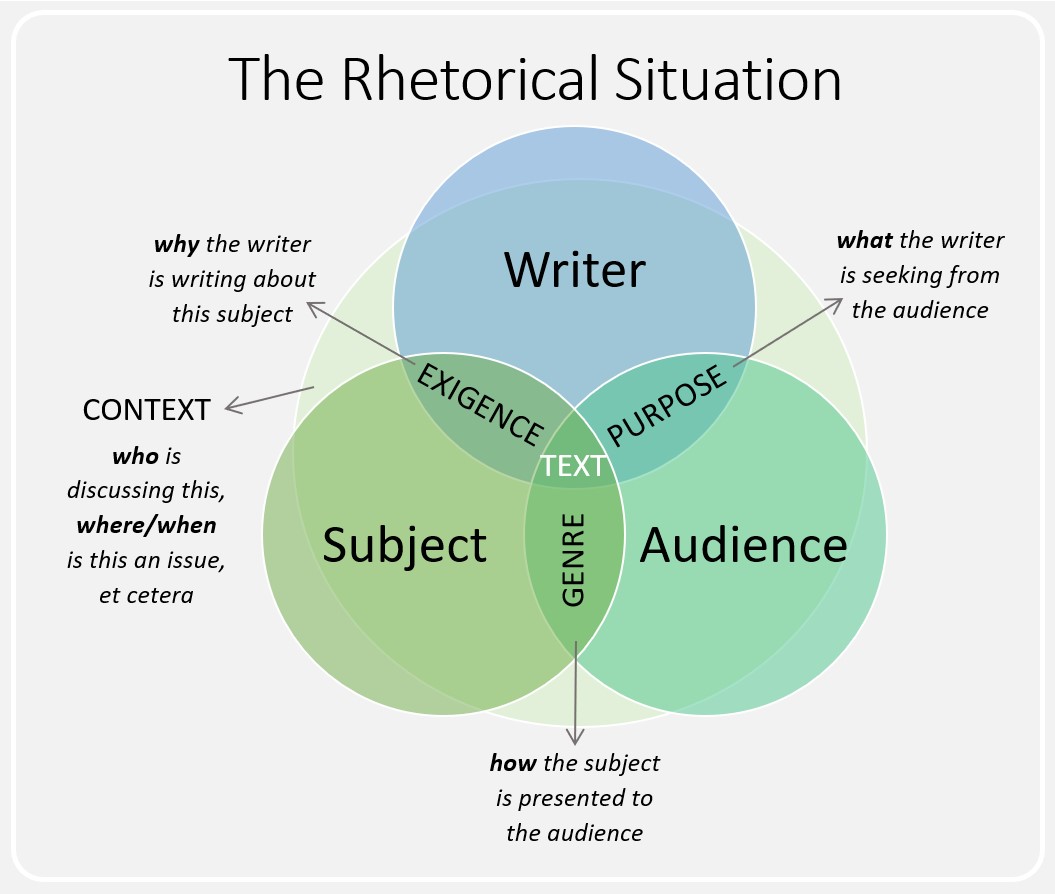

This image shows how the various elements of the Rhetorical Situation interact.

If you look closely, you should notice that the text is positioned where all of the various elements overlap.