In this Chapter

Now that you’ve learned the specific details about argument and rhetoric, it’s time to synthesize what you’ve learned–or put this information all together–so you can apply your new knowledge to the specific context of college-level writing.

Let’s return to Burke’s parlor once more to see exactly what that means.

Imagine that you’ve walked into a crowded room. Everyone there is already in conversation, and they all seem to be talking about the topic of music. You listen for a few minutes and start picking up on themes in that larger conversation. One theme is the discussion about who is the greatest musical artist of all time.

If you join a group of your friends, people with whom you already share common interests or common understandings, your conversation will go in one direction.

But what if you happen to join a group where you don’t know anyone? Because you now understand that all communication happens in a specific rhetorical situation, you decide to listen for a few minutes before speaking. As you listen, you realize that most of the people in this specific circle are experts: they’re music journalists or professors of music or even musicians themselves.

You don’t necessarily have this expertise.

Maybe you know a little about music. Maybe you know what you like. Maybe you don’t particularly care about or know much about music. Whatever the case, the group turns to you and waits for you to speak. They want to hear what you think about the topic. You know instinctively that a general opinion won’t earn you any respect in this particular situation.

Audience of Writing in College

Writing in a college course is a little like joining this group of experts. The primary audience for the writing you will do for your college classes (your professors) are experts in the topic you’ll be writing about. They have specific training and expectations about what counts as an academic argument. They expect student writers will learn about the topic at hand and demonstrate the breadth and depth of their learning in their essays and other writing tasks. They aren’t interested in uninformed opinions. But they also believe in their students’ abilities. They believe that students can and should take part in the on-going conversations of their discipline.

Context of Writing in College

The context for the writing you will do in college is the specific course you are taking. This course will be part of a larger discipline, or subject, with its own values and rules. Unlike the group of your friends talking about music on the other side of the parlor, the conversations you’ll be joining in your college courses require you to address topics in a particular way. They require you to meet the expected conventions of academic writing.

Purpose of Writing in College

The purpose for academic writing is also higher stakes than simply talking things over with a group of friends. Students write in college courses to demonstrate mastery of knowledge or skills, but they do so primarily to earn credit toward post-secondary degrees and credentials. In college courses, simply writing something isn’t enough. Hard work also isn’t enough. The essays and the work students do for their courses has to meet the requirements of the course. In college, students cannot earn credit or a credential for effort.

While each discipline or class will have it’s own specific requirements, but students who want to be successful in college-level courses in general will learn meet the basic conventions of academic writing. Let’s take a moment to review those features.

Features of Academic Writing: A Review

Let’s return back to a few of the statements about the features of academic writing you read in the first chapter.

Features of Academic Writing

Academic writing addresses specific contexts.

Academic writing is argumentative.

Academic writing is rhetorical.

Academic is well sourced.

Academic writing is focused and structured.

Academic writing is formal and unbiased.

Academic writing is clear and correct.

Academic writing, then, values writing that is argumentative and clear. Academic writing should be directed to a specific context and meet the needs of that rhetorical situation. Writing you do for academic contexts should be focused and structured, formal and unbiased. Clear and correct. Perhaps most of all, academic arguments must also be well sourced.

As we discussed in the first chapter, well sourced means that the sources used to support an argument are authoritative, relevant, and appropriate. But how can you know if you’re picking the right type of sources or sources that are appropriate for the situation at hand?

Students can be sure they are selecting the best sources for their writing by applying their knowledge of argument and rhetoric to the texts they are reading.

Reading Critically

Reading critically does not simply mean being moved, affected, informed, influenced, and persuaded by a piece of writing. It refers to analyzing and understanding the overall composition of the writing as well as how the writing has achieved its effect on the audience.

Let’s return back to the crowded room and the on-going conversation about who is the greatest musical artist of all time. You take a few minutes to listen to the various voices in the conversation. Some seem louder than others. Some provide emotional appeals, while others provide facts and statistics to back up their claims. Still others are charismatic and feel convincing, even if they don’t seem to offer any real evidence for their beliefs.

Which voices should you listen to? Which voices should you use to build your own argument?

Reading a text critically for its authority, relevance, and appropriateness to the situation can help you be sure that you’re selecting the best possible evidence.

Critical reading requires you to consider many different aspects of a writer’s work. Do not just consider what the text says. Also think about what effect the author intends to produce in a reader or what effect the text has had on you as the reader. For example, does the author want to persuade, inspire, provoke humor, or simply inform the audience? Look at the process through which the writer achieves (or does not achieve) the desired effect and which rhetorical strategies are used. If you disagree with a text, what is the point of contention? If you agree with it, how do you think you can expand or build upon the argument put forth?

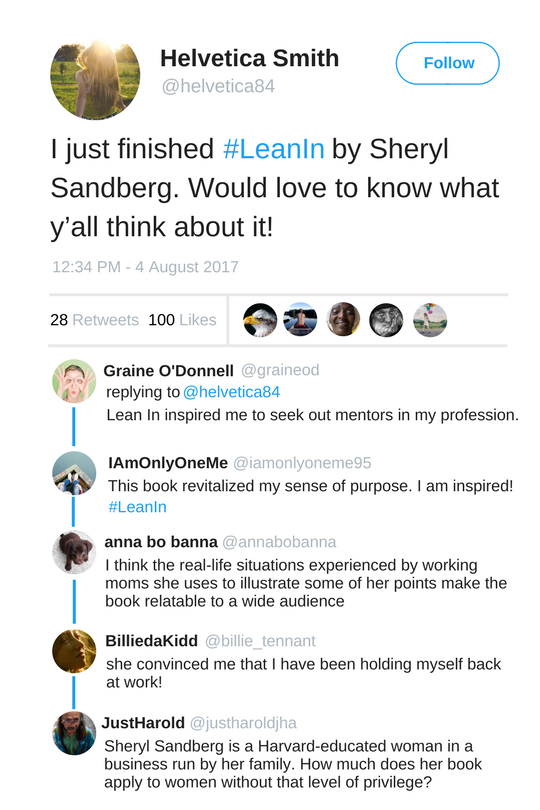

Consider the example below. Which of the following tweets below are critical and which are uncritical?

Why do we read critically?

Critical reading has many uses. If applied to a work of literature, for example, it can become the foundation for a detailed textual analysis. With scholarly articles, critical reading can help you evaluate their potential reliability as future sources.

Finding an error in someone else’s argument can be the entry point that you need to make a worthy argument of your own. The final tweet above illustrates this. By thinking critically about who the author Sheryl Sandburg is, this reader draws attention to a weakness in Sandburg’s book. If Sandburg is herself highly privileged, how could she possibly speak to women without that sense of privileged? Reading Lean In without thinking critically or analyzing its rhetorical argument might lead to simply accepting everything on the page as true or accurate. But by thinking critically the user @JustHarold draws attention to a problem with Sandburg’s argument and provides a place to enter the conversation.

Critical reading is required for academic writing. Practicing the skill of critical reading takes time and effort, but through practice you can hone your own argumentation skills. Critical reading requires a writer to think carefully about which strategies are effective for making arguments, and especially in this age of social media and instant publication where information is so easy to obtain, thinking carefully about what information we use or present is an absolute necessity.

How to Read Critically

Reading does not come naturally. It is not an instinct that you were born with — rather, it is a cultural development that began 6,000 years ago when humans began to use symbols to represent ideas. The process of reading is learned through instruction and recruits brain mechanisms that evolved for other purposes.

In other words, you weren’t born to read. Reading is a learned skill that relies on interaction nature, nurture, and culture. It is a cognitive tool that is developed through learning and practice. So what reading strategies are already in your toolbox? What strategies can you add to your toolbox to become a more efficient and effective college reader?

Initial Questions

One of the best ways to practice critical reading is to ask questions.

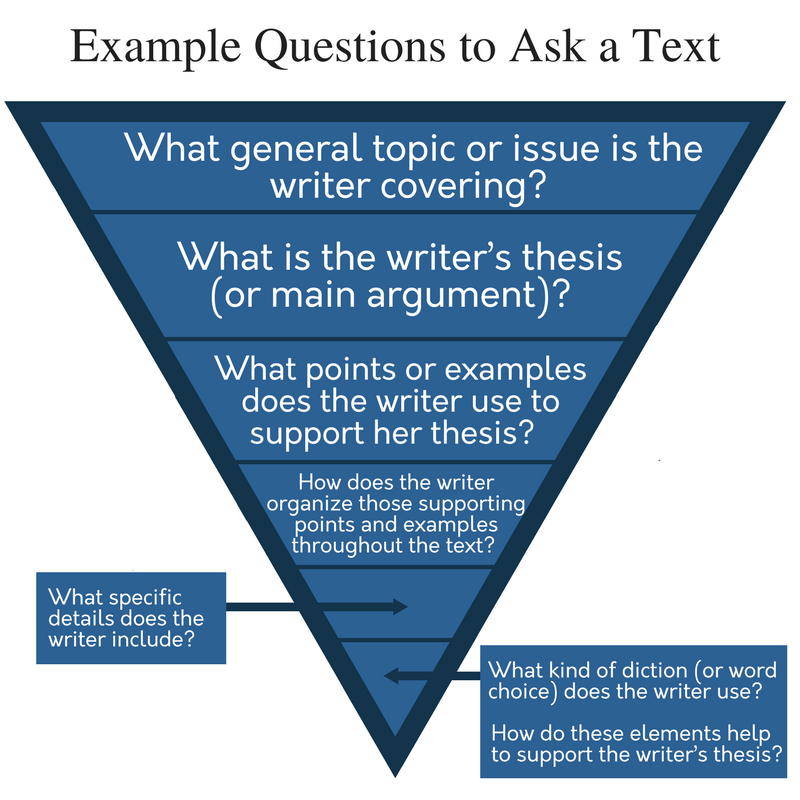

Inquiry-based learning, which is based on asking questions, is often the basis for writing and research at the college level. Specific questions generated about the text can guide your critical reading process and help you when writing a formal analysis.

When reading critically, you should begin with broad questions and then work towards more specific questions.

In order to develop good questions before reading a text, you will want to think about your purpose for reading.

- Why did your professor assign the particular text or research project?

- How does the text connect to topics you have been discussing in class or to other assigned readings?

For example, during the first unit of this course, you will be reading articles from a book titled Bad Ideas About Writing. These articles will cover topics about First-Year Composition, Academic Writing, Standardized Grammar, and the Five Paragraph Essay.

Why would your professor assign articles on these topics? It is likely that your professor wants you to read a variety of perspectives on the topic of academic writing so that you can begin to “listen” to other voices before deciding on your own opinions and arguments. In that case, you’ll want to ask a question such as, What is the author’s view on the topic? How does this view align with or differ from other views.

Perhaps, you are reading these articles in preparation of writing your own argumentative essay. It’s likely that your professor wants students to see how other authors have crafted their arguments. In that case, a good question might be, How does the article or author introduce other people’s views on this topic and how can that help me in my own writing?

Questions For Further Inquiry

In addition to asking questions of the text and author to determine the authority, relevance, and appropriateness of a text, you will want to think beyond the text to the larger conversation.

- What does this argument tell you about the larger topic?

- How does the writer address the ongoing conversation?

Thinking beyond the text at hand to the larger conversation is a crucial step in the process of academic writing.

For example, as you read the texts about First Year Composition and Academic Writing, you should think about how this topic relates to other, related issues. Questions for further inquiry might be “How do academic standards affect underprivileged students?” or “How does the amount of information online affect students’ ability to figure out what sources are good sources?” or “How could high school teachers prepare student writers without the five-paragraph essay?”

The answer to a question such as “What types of essays does First Year Composition require?” could be easily found with a quick google search. This closed type of question closes the door to inquiry, because it leads to established facts rather than to a space where a student could make their own argument.

To develop questions for inquiry consider asking these types of questions:

- Where are there holes or gaps in the logic or evidence in this text?

- What else would you like to know about this topic beyond this text?

- How are other authors writing about this topic?

- Where are the disagreements between texts?

Reading Recursively

As you practice the active reading skills you will need for success in college-level writing, it is important to understand that reading is a recursive, rather than linear, activity. This can be a difficult concept to accept for students who might have done very little reading in high school.

In college courses, it is rare that you will read a text in college once, straight through from beginning to end. Especially as students encounter more complex and sophisticated resources, they may find that they need to read a sentence or paragraph several times to understand it.

Plan on reading a text more than once: first for general understanding, and then to analyze and synthesize the material. Reading actively and recursively is the secret to becoming an effective reader.

- First Reading – Focus on the literal meaning of the text. What is the author “saying”? Annotate the text or take notes to keep track of the thesis and key points. Use strategies for unfamiliar vocabulary.

- Second Reading – Focus on “how” the author is communicating. What literary or rhetorical techniques does the author use? Pretend you are having a conversation with the author. What questions do you have? Are there any gaps in the narrative, evidence, or conclusions?

- Further Readings – Are you ready to join in the academic conversation? What additional questions do you have to further guide you inquiry into this topic? How does the text relate to other readings, class discussions, or “real world” situations? Here are a few questions to consider:

- What ideas/passages did you find most/least interesting?

- What did you learn from the reading that you did not know before?

- Did the author succeed in changing your view on the topic? Why or why not?

- What elements of the text did you connect with the most?

- What problems do you have with the text?

Final Thoughts

Few students are excited to learn that college will require more attention and engagement to more difficult readings. But one thing to keep in mind is, like any skill, critical reading does get easier, faster, and more efficient with practice. The more a student consciously attempts to analyze and read texts critically, the better they become at the skill.

Reflect on Your Reading

- What type of reading were you required to do in classes before this one? How much time do you typically take to make sure that you understand a text before citing it or using it in an essay?

- How does this discussion of critical reading change your perception of what might be expected of you in your college-level classes? Did anything surprise you?

Portions of this chapter are remixed from: “Critical Reading” by Elizabeth Browning; Karen Kyger; and Cate Bombick