In This Chapter:

Many college courses require students to locate and use secondary sources in a research paper. Educators assign research papers because they require you to find your own sources, confront conflicting evidence, and blend diverse information and ideas—all skills required in any professional leadership role. This chapter will review some of the basic guidelines for understanding and finding outside sources.

Types of Sources

There are three types of sources: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary (reference).

Primary Sources:

Primary sources are documents, images or artifacts that provide firsthand testimony or direct evidence concerning an historical topic under research investigation. Primary sources are original documents created or experienced contemporaneously with the event being researched. Primary sources enable researchers to get as close as possible to what actually happened during an historical event or time period.

Secondary Sources:

Secondary sources are works that analyze, assess or interpret an historical event, era, or phenomenon, generally utilizing primary sources to do so. Secondary sources often offer a review or a critique. Secondary sources can include books, journal articles, speeches, reviews, research reports, and more. Generally speaking, secondary sources are written well after the events that are being researched.

Tertiary (Reference) Sources:

Tertiary sources are sources that identify and locate primary and secondary sources. These can include bibliographies, indexes, abstracts, encyclopedias, and other reference resources; available in multiple formats, i.e. some are online, others only in print. It is important to note that these categories, i.e. secondary and tertiary, are not mutually exclusive. A single item may be primary or secondary (or even tertiary) depending on your research topic and the use you make of that item.

Levels of Source Authority

Why is it that even the most informative Wikipedia articles are still often considered illegitimate? What are good sources to use instead?

Above all, follow your professor’s guidelines for choosing sources. They may have requirements for a certain number of articles, books, or websites you should include in your paper. Be sure to familiarize yourself with your professor’s requirements before beginning your research.

The table below summarizes types of secondary sources in four tiers. All sources have their legitimate uses, but the top-tier ones are considered the most credible for academic work.

Figure 6.1 Source Authority Table

|

Tier |

Type |

Content |

Uses |

How to find them |

|

1 |

Peer-reviewed academic publications |

Rigorous research and analysis |

Provide strong evidence for claims and references to other high-quality sources |

Academic article databases from the library’s website |

|

2 |

Reports, articles, and books from credible non-academic sources |

Well researched and even-handed descriptions of an event or state of the world |

Initial research on events or trends not yet analyzed in the academic literature; may reference important Tier 1 sources |

Websites of relevant government/nonprofit agencies or academic article databases from the library’s website |

|

3 |

Short pieces from newspapers or credible websites |

Simple reporting of events, research findings, or policy changes |

Often point to useful Tier 2 or Tier 1 sources, may provide a factoid or two not found anywhere else |

Strategic Google searches or article databases including newspapers and magazines |

|

4 |

Agenda-driven or uncertain pieces |

Mostly opinion, varying in thoughtfulness and credibility |

May represent a particular position within a debate; more often provide keywords and clues about higher quality sources |

Non-specific Google searches |

Tier 1: Peer-Reviewed Academic Publications

Sources from the mainstream academic literature include books and scholarly articles. Academic books generally fall into three categories: (1) textbooks written with students in mind, (2) academic books which give an extended report on a large research project, and (3) edited volumes in which each chapter is authored by different people.

Scholarly articles appear in academic journals, which are published multiple times a year to share the latest research findings with scholars in the field. They’re usually sponsored by an academic society. To be published, these articles and books had to earn favorable anonymous evaluations by qualified scholars. Who are the experts writing, reviewing, and editing these scholarly publications? Your professors. We describe this process below. Learning how to read and use these sources is a fundamental part of being a college student.

Tier 2: Reports, articles, and books from credible non-academic sources

Some events and trends are too recent to appear in Tier 1 sources. Also, Tier 1 sources tend to be highly specific, and sometimes you need a more general perspective on a topic. Thus, Tier 2 sources can provide quality information that is more accessible to non-academics.

There are three main categories:

Official Reports from Government Agencies or International Institutions: these institutions generally have research departments staffed with qualified experts who seek to provide rigorous, even-handed information to decision-makers.

Feature articles from major newspapers and magazines like The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, London Times, or The Economist are based on original reporting by experienced journalists (not press releases) and are typically 1500+ words in length.

Books from non-academic presses that cite their sources, often written by journalists.

All three of these sources are generally well researched descriptions of an event or state of the world, undertaken by credentialed experts who generally seek to be even-handed. It is still up to you to judge their credibility. Your instructors, librarians, or writing center consultants can advise you on which sources in this category have the most credibility.

Tier 3. Short pieces from periodicals or credible websites

A step below the well-developed reports and feature articles that make up Tier 2 are the shorter articles that one finds in newspapers and magazines or credible websites.

How short is a short news article? Usually, they’re just a couple paragraphs or less, and they’re often reporting on just one thing: an event, an interesting research finding, or a policy change. They don’t take extensive research and analysis to write, and many just summarize a press release written and distributed by an organization or business. They may describe corporate mergers, newly discovered diet-health links, or important school-funding legislation.

You may want to cite Tier 3 sources in your paper if they provide an important factoid or two that isn’t provided by a higher-tier piece, but if the Tier 3 article describes a particular study or academic expert, your best bet is to find the journal article or book it is reporting on and use that Tier 1 source instead. Sometimes you can find the original journal article by putting the author’s name into a library database.

What counts as a credible website in this tier? You may need some guidance from instructors or librarians, but you can learn a lot by examining the person or organization providing the information (look for an “About” link on the website). For example, if the organization is clearly agenda-driven or not up-front about its aims and/or funding sources, then it definitely isn’t a source you want to cite as a neutral authority. Also look for signs of expertise. A tidbit about a medical research finding written by someone with a science background carries more weight than the same topic written by a policy analyst. These sources are sometimes uncertain, which is all the more reason to follow the trail to a Tier 1 or Tier 2 source whenever possible. The better the source, the more supported your paper will be.

Tip

It doesn’t matter how well supported or well written your paper is if you don’t cite your sources! A citing mistake or a failure to cite could lead to a failing grade on the paper or in the class.

Tier 4. Agenda-driven or pieces from unknown sources

This tier is essentially everything else.

These types of sources—especially Wikipedia—can be helpful in identifying interesting topics, positions within a debate, keywords to search, and, sometimes, higher-tier sources on the topic. They often play a critically important role in the early part of the research process, but they generally aren’t (and shouldn’t be) cited in the final paper.

Tip

Try to locate a mixture of different source types for your assignments. Some of your sources can be more popular, like Tier 3 websites or encyclopedia articles, but you should also try to find at least a few Tier 1 or Tier 2 articles from journals or reputable magazines/newspapers.

Scholarly or Academic Sources

Most of the Tier 1 sources available are academic articles, also called scholarly articles, scholarly papers, journal articles, academic papers, or peer-reviewed articles. They all mean the same thing: a paper published in an academic journal after being scrutinized anonymously and judged to be sound by other experts in the specific field.

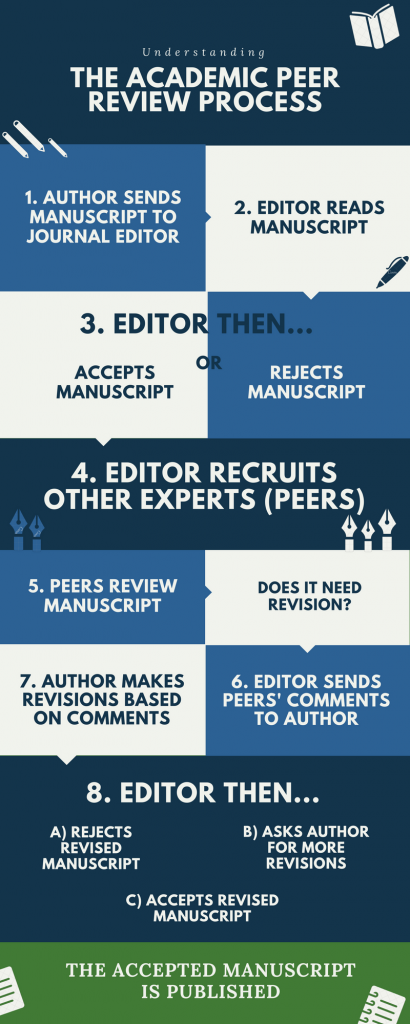

Academic articles are essentially reports that scholars write to their peers—present and future—about what they’ve done in their research, what they’ve found, and why they think it’s important. Scholarly journals and books from academic presses use a peer-review process to decide which articles merit publication. The whole process, outlined below, can easily take a year or more!

Figure 6.2 Understanding the Academic Peer Review Process

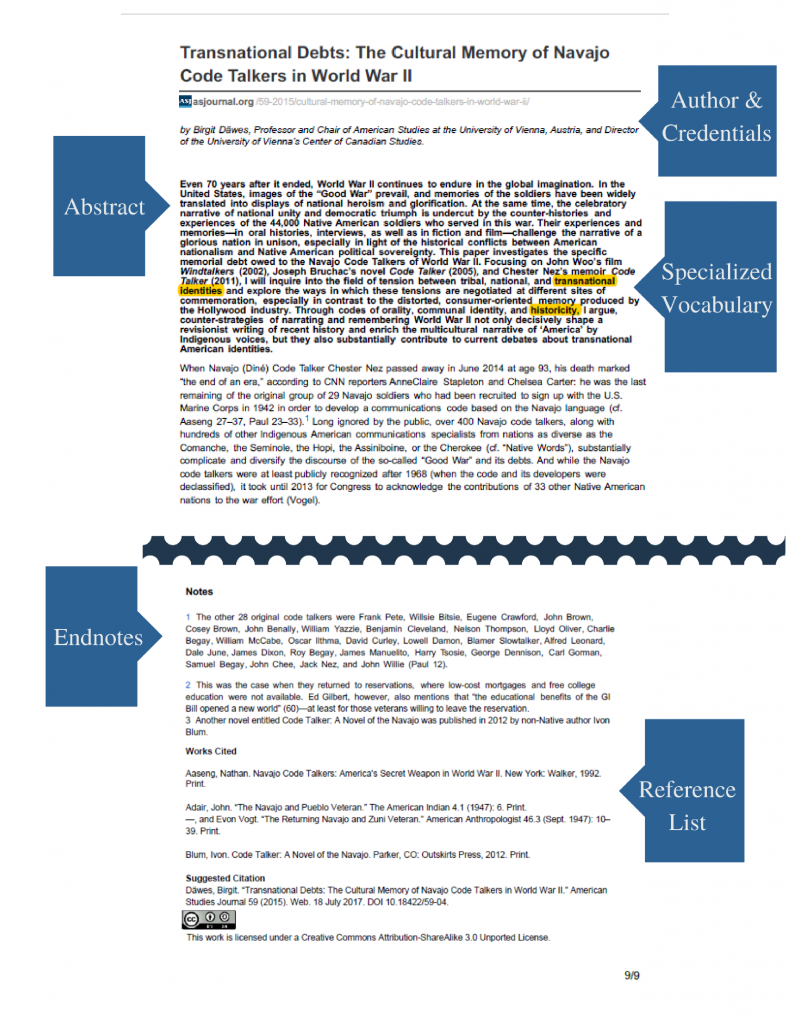

When you are trying to determine if a source is scholarly, look for the following characteristics:

- Structure: The full text article often begins with an abstract or summary containing the main points of the article. It may also be broken down into sections like “Methods,” “Results,” and “Discussion.”

- Authors: Authors’ names are listed with credentials/degrees and places of employment, which are often universities or research institutions.The authors are experts in the field.

- Audience: The article uses advanced vocabulary or specialized language intended for other scholars in the field, not for the average reader.

- Length: Scholarly articles are often, but not always, longer than the popular articles found in general interest magazines like Time, Newsweek, National Geographic, etc. Articles are longer because it takes more content to explore topics in depth.

- Bibliography or Reference List: Scholarly articles include footnotes, endnotes or parenthetical in-text notes referring to items in a bibliography or reference list. Bibliographies are important to find the original source of an idea or quotation.

Figure 6.3 Example Scholarly Source

Tip

Scholarly sources, like academic journal articles, are the most complex and authoritative sources that a writer can use when writing an academic essay. However, because these articles are intended for an audience of peers within specific disciplines, not all scholarly articles are appropriate for FYC students. Some peer reviewed articles will depend on highly specific scientific or statistical knowledge.

Using Academic Sources requires students to take the time and make the effort to read them carefully and completely.

Don’t attempt to use or cite from a source unless you are willing and able to take the time to read through and understand it. A key signal that a student is misrepresenting a sources is when they cite from academic articles that only a very advanced researcher would be able to understand. Doing so does not increase your authority to write or the essay’s effectiveness.

Creating a Research Strategy

Now that you know what to look for, how should you go about finding academic sources? Having a plan in place before you start searching will lead you to the best sources.

Research Questions

Many students want to start searching using a broad topic or even their specific thesis statement. If you start with too broad of a topic, your search results list will overwhelm you. Imagine having to sort through thousands of sources to try to find ones to use in your paper. That’s what happens when your topic is too broad; your information will also be too broad.

Starting with your thesis statement usually means you have already formed an opinion about the topic. What happens if the research doesn’t agree with your thesis? Instead of closing yourself off to one side of the story, it’s better to develop a research question that you would like the research to help you answer about your topic.

Steps for Developing a Research Question

Step 1: Pick a topic (or consider the one assigned to you).

Step 2: Write a narrower/smaller topic that is related to the first.

Step 3: List some potential questions that could logically be asked in relation to the narrow topic.

Step 4: Pick the question in which you are most interested.

Step 5: Modify that question as needed so that it is more focused.

Example:

General Topic: Cars

Narrow Topic: Self Driving Cars

Research Question: Are self-driving cars safer than those driven by people?

Keywords & Search Terms

Starting with a research question helps you figure out precisely what you’re looking for. Unlike using Google, library databases require the use of keywords to search. Once you have your research question, you’ll need the most effective set of search terms – starting from main concepts and then identifying related terms. These keywords will become your search terms, and you’ll use them in library databases to find sources.

Identify the keywords in your research question by selecting nouns important to the meaning of your question and leaving out words that don’t help the search, such as adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and, usually, verbs. Nouns that you would use to tag your research question so you could find it later are likely to be its main concepts.

Example: How are birds affected by wind turbines?

The keywords are birds and wind turbines. Avoid terms like affect and effect as search terms, even when you’re looking for studies that report effects or effectiveness.These terms are common and contain many synonyms, so including them as search terms can limit your results.

Example: What lesson plans are available for teaching fractions?

The keywords are lesson plans and fractions. Stick to what’s necessary. For instance, don’t include: children—nothing in the research question suggests the lesson plans are for children; teaching—teaching isn’t necessary because lesson plans imply teaching; available—available is not necessary.

Keywords can improve your searching in all different kinds of databases and search engines. Try using keywords instead of entire sentences when you search Google and see how your search results improve.

For each keyword, list alternative terms, including synonyms, singular and plural forms of the words, and words that have other associations with the main concept. Sometimes synonyms, plurals, and singulars aren’t enough. Also consider associations with other words and concepts. For instance, it might help, when looking for information on the common cold, to include the term virus—because a type of virus causes the common cold.

Once you have keywords and alternate terms, you are prepared to start searching for sources in library search engines called databases.

Example:

Research Question: Are self-driving cars safe?

Keywords: Self driving cars, safety

Alternate terms: autonomous vehicles, Google Cars, Waymo project, Tesla, accidents, driver protection, security, crashes

Finding Credible Sources

There are two main methods of finding sources: library research and general internet research. A later chapter will cover the specific needs of the research you do using the internet with search engines such as Google or websites like Wikipedia. An easier way to find credible sources is through your college library, especially using online databases.

Library Sources

Every college library subscribes to a collection of databases (search engines) for credible, academic sources. Research done through these paid, subscription-based databases can usually be considered reliable, authoritative, and appropriate for your college level courses. While you will have to make sure the particular source is appropriate for the specific writing assignment, you usually do not have to check sources you find through databases for reliability or correctness.

Databases range from general to very specific. Some general purpose databases include the most prominent journals in many disciplines, while others are specific to a particular discipline. Prince George’s Community College includes a database list of more than a hundred database options. You can search for a database by subject categories, or you can use the alphabetical list of databases.

Internet Resources

Because literally anyone can publish anything on the internet, sources that you find through general internet research much be checked for reliability, correctness, and source authority. While there are excellent resources available in the general internet, especially through professional or government organizations, most of the best and most reliable sources you find online will be behind a paywall. You can usually find these same sources through your college’s library, since they will have subscriptions to most of the most popular and important publications.

Every source found from a general internet search, such as through Google, must be evaluated for reliability and accuracy. See the later chapter on the C.R.A.A.P. Test for more specific information.

Tip

If you can’t find the sources you need, visit the Reference Desk, use the “Chat with a Librarian” feature, or set up an appointment for one-on-one help from a librarian. You can find the library’s hours and contact information on the PGCC Library Website. The Campus Writing Center tutors can also provide research help.

Additional Links

Scholarly Source Annotation, (http://libguides.radford.edu/scholarly) Radford University

CC-Licensed Content, Shared Previously

Choosing & Using Sources: A Guide to Academic Research. Cheryl Lowry, ed., CC-BY.

Writing in College: From Competence to Excellence. Amy Guptill, CC BY-NC-SA.

Image Credits

Figure 6.1 “Source Type Table,” Writing in College: From Competence to Excellence, by Amy Guptill, Open SUNY, CC-BY-SA-NC.

Figure 6.2 “Understanding the Academic Peer Review Process,” Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0.

Figure 6.3 “Example Scholarly Source”, Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-BY-SA, derivative image from “Transnational Debts: The Cultural Memory of Navajo Code Talkers in World War II” in American Studies Journal, by Birgit Dawes, American Studies Journal, CC-BY-SA.