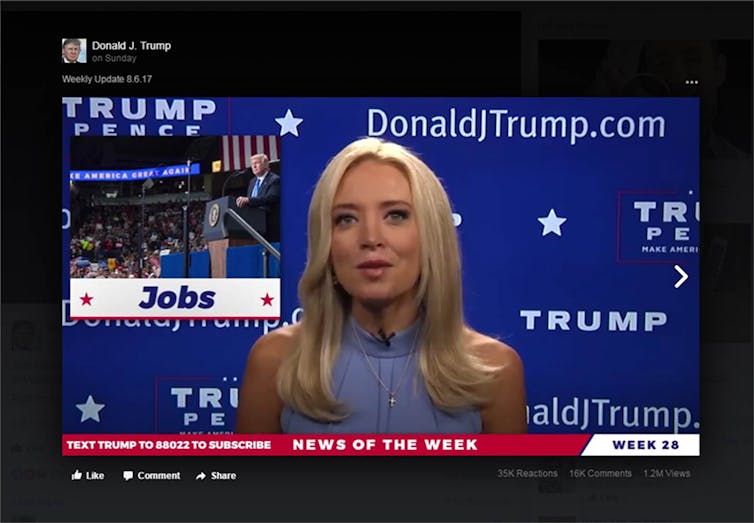

Donald J. Trump/Facebook

John Keane, University of Sydney

This article is part of the Revolutions and Counter Revolutions series, curated by Democracy Futuresas a joint global initiative between the Sydney Democracy Network and The Conversation. The project aims to stimulate fresh thinking about the many challenges facing democracies in the 21st century.

It is also part of an ongoing series from the Post-Truth Initiative, a Strategic Research Excellence Initiative at the University of Sydney.

This essay is much longer than most Conversation articles, so will take some time to read. Enjoy!

We live in an unfinished revolutionary age of communicative abundance. Networked digital machines and information flows are slowly but surely shaping practically every institution in which we live our daily lives.

For the first time in history, thanks to built-in cheap microprocessors, these algorithmic devices and information systems integrate texts, sounds and images in compact, easily storable, reproducible and portable digital form.

Communicative abundance enables messages to be sent and received through multiple user points, in chosen time, real or delayed, within global networks that are affordable and accessible to billions of people.

My book Democracy and Media Decadence probed the contours of this revolution. It showed why new information platforms, robust muckraking and cross-border publics are among the exciting social and political trends of our time. It proposed that the unfinished revolution is dogged by politically threatening contradictions and decadent counter-trends. The drift toward a world of “post-truth” politics is among these troubling trends.

What exactly is meant by the term post-truth? Paradoxically, post-truth is among the most-talked-about yet least-well-defined meme words of our time. Most observers in the English-speaking world cite the 2016 Word of the Year Oxford English Dictionaries entry: post-truth is the public burial of “objective facts” by an avalanche of media “appeals to emotion and personal belief”.

In China and in the Spanish-speaking world, respectively, commonplace talk of hòu zhēnxiāng and posverdad pushes in this direction. The popularity of the German postfaktisch (post-factual) usage captures much the same meaning. Selected as word of the year by the German language society Gesellschaft für deutsche Sprache (GfdS), it refers to the growing tendency of “political and social discussions” to be dominated by “emotions instead of facts”.

The GfdS adds:

Ever greater sections of the population are ready to ignore facts, and even to accept obvious lies willingly. Not the claim to truth, but the expression of the ‘felt truth’ leads to success in the ‘post-factual age’.

Post-truth communication

A catchword that has gone viral so quickly surely deserves careful attention and crisper definition, especially if we are not to be thrown off balance by a global phenomenon that sets out to do precisely that.

We can say that “post-truth” is not simply the opposite of truth, however that is defined; it is more complicated. It is better described as an omnibus term, a word for communication comprising a salmagundi or assemblage of different but interconnected phenomena.

Its troubling potency in public life flows from its hybrid qualities, its combination of different elements in ways that defy expectations and confuse its recipients.

Post-truth has recombinant qualities. For a start, it is a type of communication that includes old-fashioned lying, where speakers say things about themselves and their world that are at odds with impressions and convictions that they harbour in their mind’s eye.

Liars attempt alchemy: when someone tells lies they wilfully say things they “know” not to be true, for effect. An example is when Donald Trump claims there was never a drought in California, or that during his inauguration the weather cleared, when actually light rain fell throughout his address.

Post-truth also includes forms of public discourse commonly called bullshit. It comprises communication that displaces and nullifies concerns about veracity. Bullshit is hot air talk, verbal excrement that lacks nutrient. It is shooting off at the mouth, backed by the presumption that it is acceptable to others in the conversation.

Post-truth depends as well on buffoonery, bits and pieces of colourful communication designed to attract and distract public attention and to interrupt the background noise of conventional politics and public life. The bric-a-brac component of post-truth includes nonsense moments, jokes and boasting. It embraces clever quips, pedantry and wilful exaggerations (like Marine Le Pen’s description of the European Union as “a huge prison”).

There is plenty of rough speech. The contrast with the honey words and smiles of Bill Clinton, Felipe González, Tony Blair and other politicians from yesteryear is striking. The grotesquerie comes in abundance. Geert Wilders specialises in causing trouble, as when he dubs mosques “palaces of hatred”.

Disturbingly, there’s abundant talk of the importance of “truth”, by which is usually meant utterances whose veracity is self-confirming, thus proving that truth can attract rogues. There is dog-whistling. There is plain bad taste, as when a newly elected president enters the Houston Astrodome, crammed with traumatised homeless people who have narrowly survived a hurricane, and says: “Thanks for coming.”

Hair-splitting and wilfully setting things aside are common. The Israeli consul-general in New York, Dani Dayan, does this well, but the genius of evasion is surely Zoltán Kovács, the Orbán government’s spokesman. When subjected to forensic questioning by reporters about Hungary’s imprisonment and brutal maltreatment of refugees and operations by vigilante citizens’ “hunter patrol” border forces, he likes to say:

What you are trying to portray here is non-existent, a gross simplification. Next question.

And that’s that.

Engineered silence

The silencing is not incidental. Post-truth performances feed on their production of silence. They remind us, in the words of Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, that:

… the stupendous reality that is language cannot be understood unless we begin by observing that speech consists above all in silences.

The proponents of post-truth communication relish things unsaid. Their bluff and bluster is designed not only to attract public attention.

It simultaneously hides from public attention things (such as growing inequalities of wealth, the militarisation of democracy and the accelerating death of non-human species) that it doesn’t want others to notice, or that potentially arouse suspicions of the style and substance of post-truth politics.

This engendered silence is not just the aftermath or “leftover” of post-truth communication. Every moment of post-truth communication using words backed by signs and text is actively shaped by what is unsaid, or what is not sayable.

The communicative performances of the post-truth champions are thus the marginalia of silence: mere foam and waves on its deep waters.

That is why the current hyper-concentration of journalists and other public commentators on “breaking news” stories about “fake news”, “alternative facts” and missing “evidence” is so potentially misleading.

Their fetish of breaking news turns them unwittingly into the poodles of post-truth and its silence about things less immediate and less obvious, deeper institutional trends, “slower” events marked by punctuated rhythms.

Vaudeville and gaslighting

Treating post-truth as a species of pugnacious politics dressed in a coat of many colours, as a bricolage of lies, bullshit, buffoonery and silence, helps us grasp its vaudeville quality.

When thought of as a public performance led by a cast of politicians, journalists, public relations agencies, think tanks and other players, post-truth is an updated, state-of-the-art political equivalent of early 20th-century vaudeville performances.

Old-fashioned vaudeville featured strongmen and singers, dancers and drummers, minstrels and magicians, acrobats and athletes, comedians and circus animals. It was a show. Post-truth is equally a show. Directed against conventional styles of performance, it is an orchestrated public spectacle designed to invite and entertain millions of people.

But post-truth is much more than entertainment, or the “art of contrivance” or the “dictatorship of illusion” mediated by the production and passive consumption of commodities.

While the genealogy of post-truth is partly traceable to the world of corporate advertising and market-driven entertainment, it has thoroughly political qualities. In the hands of the powerful, or those bent on climbing the ladders of power over others, the post-truth phenomenon functions as a new weapon of political manipulation.

Post-truth is not only about winning votes, siding with friends, or dealing with political foes. It has more sinister effects. It is a gaslighting exercise.

Wikipedia Commons

Drawn from George Cukor’s award-winning Gaslight, starring Ingrid Bergman and Charles Boyer, the term gaslighting is here defined as a weapon of the will to power. It is the organised effort by public figures to mess with citizens’ identities, to deploy lies, bullshit, buffoonery and silence for the purpose of sowing seeds of doubt and confusion among subjects.

Gaslighting is typically a preferred tactic of narcissistic and aggressive personalities bent on doing whatever it takes to gain and maintain a position of advantage over others.

Their point is to disorient and destabilise people. They want to harness people’s self-doubts, ruin their capacity for seeing the world ironically, destroy their capacity for making judgements, in order to drive them durably into submission.

When (for instance) gaslighters say something, only later to say that they never said such a thing and that they would never have never dreamed of saying such a thing, their aim is gradually to turn citizens into mere playthings of power.

When that happens, the victims of gaslighting no longer trust their own judgements. They buy into the tactics of the manipulator. Not knowing what to believe, they give up, shrug their shoulders and fall by default under the spell of the gaslighter.

Consider the double act of Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte and his former right-hand gaslighter, Ernesto Abella, in the sequence of events triggered by the murder (in November 2016) of Rolando Espinosa, the elected mayor of Albuera, an island community some 575 kilometres from Manila.

When asked by journalists to explain what had happened, Duterte reportedly said:

He was killed in a very [questionable way], but I don’t care. The policemen said he resisted arrest. Then I will stick with the story of the police because [they are] under me.

Espinosa was in fact shot in detention, inside a police cell.

Duterte continued:

I might go down in history as the butcher. It’s up to you.

And then:

Since I have nothing to show, I just use extrajudicial killing. [That’s because] I have no credentials to boast about.

The intended meaning of these utterances (to put things mildly) was oracular, so mystifyingly opaque that they served as the cue for Abella to strut his stuff: to go on air and to say that this or that never happened, that Duterte never said what people heard him say, that Bisaya-speaking Duterte got lost in translation when speaking in Tagalog, to affirm at Malacañang press conferences that his intentions are good and that he is utterly sincere, whereas his enemies are wilful dissemblers, fools and toads.

Abella insisted he provided not “crumbs”, but “meat, deboned”. Armed with his favourite phrases, “let’s just say” and “let’s put it this way”, he described his job as “completing the sentences” of his leader, to “impart his true intentions”.

In this murder case, Abella said, “it is … a matter of the leadership style and the messaging style of the president”. He added:

This is his messaging style to underline his intention. He is serious about it [the drug menace]. However, it’s just meant to underline his seriousness in making sure that nobody is corrupt and involved in criminality.

What makes post-truth different from the past?

The meandering rhetoric is designed to bewitch and beguile, which is why the critics of post-truth are sounding alarms and issuing stern warnings about the dangerous charms of the vaudeville show of political mendacity, nonsense, buffoonery and silence.

They emphasise that political lying and bad manners spiced with talk of “fake news” and “alternative facts” are sinister, a frontal challenge to the basic democratic norms of open and plural communication among citizens.

Complaints against post-truth are often robust, loud and couched in high moral tones. Post-truth is said to be the beginning of the end of politics as we’ve known it in existing democracies.

There is talk of an emergent “post-truth era”. More than a few critics warn that the spread of post-truth is the harbinger of a new “totalitarianism”. Others speak of populist dictatorship or “fascism-lite” government.

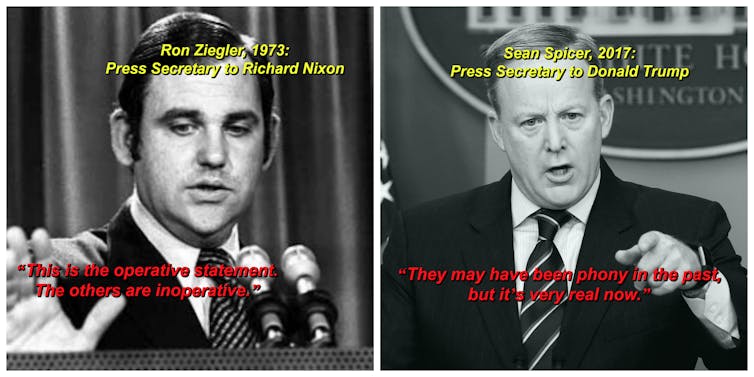

The descriptors are questionable, and display little understanding of the historical originality of the present drift towards government by gaslighting. Politics as the art of evasion, befuddlement and engineered public silence isn’t new. Lying in politics is an ancient art. Think of Plato’s noble lie, or Machiavelli’s recommendation that a successful prince must be “a great pretender and dissembler”, or Harry Truman’s description of Richard Nixon as:

… a no good, lying bastard. He can lie out of both sides of his mouth at the same time, and if he ever caught himself telling the truth, he’d lie just to keep his hand in.

Thomas Cizauskas/flickr

Some things don’t change. Still, there are several things that are unusual about the gaslighting trends of our time. Each is bound up with the unfinished communications revolution.

The digital merging and melding of text, sound and image, the advent of cheap copying and the growing ease of networked information spreading across vast distances in real time are powerful drivers of post-truth decadence.

New techniques and tools of communication are its condition of possibility; they enable its production, rapid circulation and absorption into the body politics of democracies, and well beyond.

Think of photoshopped materials and mashups, web applications and pages that recycle content from more than one source to create a single new service displayed in a single graphical interface. Trump’s first campaign advertisement showed migrants allegedly crossing the Mexican border; in fact, it was an image of migrants crossing from Morocco to Melilla in North Africa.

Then consider impostor news sites (using URLs such as abc.com.co) and fantasy news sites, such as WTOE 5 News, which created the “Pope Francis Shocks World, Endorses Trump for President” story, built using such tools as Clone Zone and NowThis.

Ponder shareable made-up news platforms (Macedonian teenagers making money, Christian fundamentalists peddling the Spirit), meme launch pads (Twitter and Facebook) and parody accounts (The Onion, “America’s Finest News Source”).

There are also the devoted fanzine platforms that specialise in hailing heroes and trolling opponents, the platforms that sit for the first time in the White House press briefing room, platforms such as Gateway Pundit, One American News Network, Newsmax, LifeZette and the Daily Caller.

Some say none of this is new. From the outset, they insist, daily newspapers printed gossip, rumours and lies. Orson Welles proved that radio could produce scams. Television was a state weapon for mass-producing fabricated illusions; and so on.

But the sceptics underestimate the multiple ways in which, in matters of truth and post-truth, the communications revolution is marked by novel dynamics that are producing novel effects.

Most obviously, the digital communications revolution tends to undermine space-time barriers so that the raw material of lies, bullshit, buffoonery and silence produced by gaslighters develops long global legs.

Post-truth spreads; it knows no borders. So, for instance, many Muslims living in countries as far apart as Britain, Pakistan and Indonesia understand that they are among the targets of the project of attacking “fake news” and making America great again.

There’s something else that’s new: post-truth discourse penetrates so deeply into our daily lives that what is commonly called the private sphere ceases to be private. It’s no longer a safe haven or a zone of counter-balance, in the way (say) it functioned as the point of resistance against total power in the age of the typewriter or in George Orwell’s 1984, where Winston was still able to retreat to a corner table to scribble, out of sight of Big Brother.

The colonisation of daily life by the so-called Internet of Things, digital robots that collect and spread information, guarantees that the geographic footprint of post-truth is vast and potentially total.

There’s yet another novelty of our period: the production and diffusion of post-truth communication by populist leaders, political parties and governments. The historical record shows that our times are no exception to the old rule that populism is a recurrent autoimmune disease of democracy.

The present-day political irruption of populism is fuelled by the institutional decay of electoral democracy, combined with growing public dissatisfaction with politicians, political parties and “politics”.

Reinforced by the failure of democratic institutions to respond effectively to anti-democratic challenges such as the growing influence of cross-border corporate power, worsening social inequality and the dark money poisoning of elections, the decadence is proving to be a lavish gift to leaders, parties and governments peddling the mantra of “the sovereign people”.

EU2017EE Estonian Presidency Follow/flickr

Populist figures otherwise as different as Viktor Orbán, Norbert Hofer and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan are oversized vaudeville characters. They are merchants of post-truth, exploiters of trust and confidence artists who take advantage of the communications revolution.

They stir up multimedia excitement by calling for a public revolt by millions of people who feel annoyed, powerless and no longer “held” (D.W. Winnicott) in the arms of society: people who are so frustrated or humiliated that they are willing to lash out in support of demagogues promising them dignity and a better future.

Some people fall for the promises not because they “naturally” crave leaders, or yield to the inherited “fascism in us all”. Among the strangest and most puzzling features of the post-truth phenomenon is the way it attracts people into voluntary servitude because it raises their hopes and expectations of betterment.

Truth is the answer? Don’t believe it

The most surprising long-term effect of communicative abundance and the spread of post-truth is arguably their reinforcement of the modern questioning and rejection of arrogant beliefs in truth.

The possibility that post-truth politics is party to the “farewell to truth” is poorly understood, especially by critics of post-truth, who invariably rally to the cause of what they casually call truth.

Although the term is usually left undefined, their attachment to truth helps explain why many academics, journalists and public commentators typically accuse the “postmodernism” of recent decades of being the unwitting accomplice or active foot servant of post-truth politics.

They are convinced that the “relativism” of the postmodernists unhelpfully adds to the confusion surrounding “truth” based on “evidence” and “facts”. What is now urgently needed, they say, is the recovery of truth.

But what is truth? Truth is the antidote to post-truth, they reply. It is observable. Truth is saying or writing or visualising, somehow depicting things that correspond to “reality”.

The champions of truth understood as adequation sometimes cite the Polish-American mathematician Alfred Tarski, who famously put things this way: the proposition that “snow is white” (“p”) is true if and only if snow is white (“p is true if and only if p”). It’s seeing language as a conveyor belt, as a medium for recording a “reality” that is external to the observer.

Tough versions of the orthodoxy insist that evidence is evidence, reality is real and “brute facts” exist independently of anyone’s attitude toward them.

It’s not only philosophers who speak in this fashion. Journalists, lawyers, more than a few academics, plenty of environmental activists and data scientists are in the truth trade.

Believers in truth, a word that is usually left undefined, they have a habit of supposing that reality is all around them, out there, within arm’s reach or just beyond arm’s length, graspable and catchable through redescription, for instance in the form of data.

Such conceptions of “objectivity” fail to rethink the whole idea of truth as a necessary condition of ridding the world of post-truth decadence. Their failure to cast doubt simultaneously upon both post-truth and truth, to see them as partners rather than as opponents, ignores the need for a new geography and history of truth.

The New York Times

Truth varies through space and time

The geography of truth highlights the spatial dimensions of truth-seeking and attempts to live the truth. What counts as truth varies from place to place.

The French Renaissance writer Montaigne famously said that what is truth on one side of the Pyrenees is falsehood on the other side. Foucault repeats the point in his account of the birth of truth-telling (le dire vrai) within clinics and prisons.

Scholarly studies of the way cities (Escuela de Salamanca, Chicago School of Economics, Copenhagen School) have shaped what counts as knowledge push in the same direction.

The geography of truth equally matters within any given society, at any given time. The Pitjantjatjara peoples of central Australia still today use a family of terms like mula and mula-mulani and mulapa to refer to a “true story” that is inscribed with both connotations of “a long time” and calls for agreement between story tellers and listeners.

When Pitjantjatjara peoples speak of truth, they understand they are engaged in efforts to convince others of the rightness of their tradition. They recognise what mainstream white society usually forgets: that truth and trust are twins.

A new geography of truth would also note that there are spaces of life that either have little or nothing to do with truth, or where references to truth are simply out of place (Bertolt Brecht once remarked that if someone stood up in front of a group of strikers and said 2+2=4 they would no doubt be jeered), or where telling the truth has dangerous consequences, as when a Rohingya father lies to a Myanmar army patrol hunting women to rape by telling them on his doorstep he has no daughters.

What counts as truth varies not only through space but also through time. Truth has a controversial history; truth has never straightforwardly been truth. There is a history of truth that shows that what counts as truth varies through time, but also (the corollary) that what is today taken as truth has not always been so.

Ancient Greek understandings of truth as aletheia, a difficult word variously translated as “disclosure” or “un-concealedness”, are evidently different than Christian understandings of “the way and the truth and the life” (John 14:6) and the imperative to tell the truth, shame the devil.

The early modern European period was marked by bitter struggles over the meaning of religious “truth”, calls for religious toleration and the deployment, by believers in truth, of such tactics of deception as occultism, the Catholic doctrine of mental reservation and Protestant casuistry.

The public controversies about truth among Christians encompassed Luther’s explosive, influential attack on popery as the sole interpreter of scripture in An Open Letter to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation Concerning the Reform of the Christian Estate (1520). They extended to Lessing’s recommendation that we should thank God that we don’t know the truth (“Sage jeder, was ihm Wahrheit dünkt, und die Wahrheit selbst sei Gott empfohlen” [“Let each person say what s/he deems truth, and let truth itself be commended unto God”]); and Tocqueville’s observation that the modern democratic revolution powerfully calls into question so-called public truths about the “natural” inferiority of slaves and women.

Democracy doubts both post-truth and ‘the truth’

The public sense that truth claims are contestable and mutable interpretations is undoubtedly bolstered by the multi-media communications revolution, and by the advent of new forms of monitory democracy featuring a plethora of mediated platforms where power is publicly interrogated and chastened.

Monitory democracy promotes the growth of public spaces where uncertainty, doubt, scepticism, irony and modesty in the face of arbitrary power are nurtured.

Wittgenstein’s recommendation that saying “I know” should be banned so that people would be required to say “I believe I know” makes good sense under these conditions. We could say that post-truth politics is the dark and messy side of an unfinished quantum shift in support of the pluralisation of people’s lived perceptions of the world.

Yes, talk of truth is not disappearing, or dead. Just as unbelievers continue to say “Lord help us” and “Jesus Christ”, and despite Copernicus people still speak of the setting sun, so the language of truth lives on in people’s lives.

Yet nowadays tropes like “We hold these truths to be self-evident” arouse public suspicions. The truth is out that truth has many faces.

What counts as “truthful information” is less and less understood by wise citizens as “hard facts” or as indisputable “evidence” or as chunks of “reality” to be mined from television and radio programs, or from newspapers, digital platforms and “expert” authorities.

In the age of communicative abundance and monitory democracy, “reality” is multiple and mutable. “Reality”, including the lies and buffoonery and other forms of gaslighting peddled by the powerful, comes to be understood as always “reported reality”, as “reality” produced by some for others – in other words, as messages that are shaped and reshaped and reshaped again in the process of transmission and reception.

This disenchantment of truth has everything to do with democracy. Considered as a universal norm liberated from metaphysical foundations, as a whole way of life committed to the defence of complex equality, freedom and difference, democracy in monitory form is the guardian of a plurality of lived interpretations of life.

The radical originality of monitory democracy is its defiant insistence that peoples’ lives are never simply given, that all things human are built on the shifting sands of space-time, and that no person or group, no matter how much “truth” or power they presently enjoy or want to claim, can be trusted permanently, in any given context, to govern other people’s lives.

Democracy is thus the best human weapon so far invented for guarding against the “illusions of certainty” and breaking up truth-camouflaged monopolies of power, wherever they operate. Democracy is not a True and Right norm. Just the reverse: the norm of monitory democracy is aware of its own and others’ limits, knows that it doesn’t know everything, and understands that democracy has no meta-historical guarantees. That is why it does not suffer truth-telling dogmatists and fools gladly.

Democracy is a living reminder that truths are never self-evident, and that what counts as truth is a matter of interpretation. Recognising that in political life “truth has a despotic character”, democracy stands for a world beyond truth and post-truth.

This is not because all women and men are “naturally” created equal. Rather, it’s because democracy supposes that no man or woman is good enough to claim they know the truth and to rule permanently over their fellows and the earthly habitats in which they dwell.

You can read other articles in the series here.

The theme of truth, post-truth and the unfinished communications revolution is further explored in a recently published thepaper.cn interview, The Revival of Truth Isn’t the Remedy for Post-Truth (available only in Chinese).![]()

John Keane, Professor of Politics, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.