3

While definitions of fiction often emphasize its fabricated nature as opposed to historical or other “factual” genres, most readers understand that truth can arise from fiction in its own special way. Think of your favorite short story or novel—what does it reveal to you about yourself? How does it illuminate the human condition? While stories can convey a variety of “truths,” which to some extent depend on each reader’s identity and experience, we still seek in these narratives connections with characters and other readers.

Up through the first part of the twentieth century, scholars often referred to these connections as “universal truths.” This term refers to experiences, feelings, and insights that are common to all people. Yet, events of the 1950s and 1960s raised questions about whether any experience was truly universal. With the Civil Rights Movement came the understanding that people’s experiences can vary wildly due to factors such as gender, class, ethnicity, and culture. Much to the surprise of many scholars (the vast majority of whom were, at the time, white, middle class, and male), not everyone could completely identify with Mark Twain’s young protagonist Huckleberry Finn.

For example, because of rigid social codes and physical risks unique to U.S. women, a young American female reader might not have the option of experiencing a physical journey like Huck’s. In fact, it might be difficult for her even to imagine taking such a trip down the Mississippi River, since there is little to no evidence in history of a woman ever having done so. Even Huck’s friend Jim, an escaped slave, is vulnerable in ways that Huck is not, as the two travel together. Readers of color might identify less with Huck’s circumstances and more with Jim’s. Even so, most readers can connect with Huck’s inner conflict as he struggles between his obligation to follow the social rules taught to him as absolute morals and his own conscience, which tells him that Jim should not be subjected to slavery.

As you form your perspective on a story and then develop that perspective in an essay, your own readers will still seek an insight that is relevant to them. Thus, while we must be sensitive to the differences among individuals’ experiences as we form an argument about a short story or novel, it is still important to forward a case based on common ground between our readers and ourselves. Consider the difference between these two assertions:

- To mature as a moral creature, Huck must separate himself from society for a time and explore the world beyond his own narrow-minded hamlet.

- Huck’s journey away from his own narrow-minded hamlet and its teachings enables his moral maturation.

Note the first assertion’s implication that if one cannot leave one’s hamlet and separate him or herself from his or her restrictive environment, one cannot mature morally. A reader who cannot take such a journey because of economic or social factors (such as having to stay at home and care for a child or work to support a family) might respond to such a pronouncement by (a) feeling condemned to stunted personal growth and inferiority, as a person excluded from this experience, or (b) becoming defensive at such a claim. On the other hand, the second assertion will likely ring true both for those who can take the journey and those who cannot. It does not suggest that the only way of achieving moral growth is to take a physical journey like Huck’s. Thus, even considering the sometimes stark differences among readers’ lives, if interpretation of literature is handled well, it can reveal our common experiences.

As a place where we can connect with one another as well as learn about ourselves, fiction indeed offers us a special brand of truth. Although history and philosophy pursue these goals as well, fiction is a narrative that is not bound to either historical events or scientific facts. The writer takes liberties with a fictional story, using his imagination to craft a plot that achieves the desired effect and meaning.

The term narrative refers to the sequence of events in a story, often suggesting a cause and effect relationship among these events. A term that captures this concept more specifically, plot is defined as the sequence of events that develops the conflict and shapes the story. Rather than tell everything that might possibly happen to a character in certain circumstances, the writer carefully selects the details that will develop the plot, the characters, and the story’s themes and messages. The writer engages in character development in order to develop the plot and the meaning of the story, paying special attention to the protagonist, or main character. In a conventional story, the protagonist grows and/or changes as a result of having to negotiate the story’s central conflict. A character might be developed through exposition, in which the narrator simply tells us about this person. But more often, the character is developed through dialogue, point of view, and description of this person’s expressions and actions.

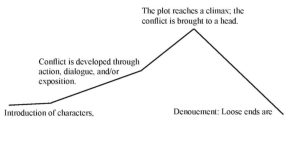

The traditional shape of a story is based on common conventions of Greek drama, as noted. With setting, situation, and conflict. tied up, often the conflict is resolved.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, ORIGINAL and REMIXED

- Chapter 5 from Writing and Literature: Composition as Inquiry, Learning, Thinking, and Communication (2018) by Tanya Long Bennett at https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/15 License: CC BY: Attribution

- Composition and Literature (2021)-License: CC BY: Attribution