5 Mapping the Terrain: Respecting Different Ways of Knowing

“Diversity in society is a universal fact; how societies respond to diversity is a choice. Pluralism is a positive response to diversity. Pluralism involves taking decisions and actions, as individuals and societies, which are grounded in respect for diversity.

The goal of pluralism is belonging. Building inclusive societies requires both institutional responses (“hardware”) and behavioural change (“software”) to ensure that every person is recognized and feels they belong.”

Purpose

“Mapping the Terrain” is informed by narrative therapy’s deep respect for viewing reality through multiple lenses. It explores the values, voices and power structures that underpin the culture of the learning community. This activity provides a way to dive into understanding the perspectives and cultures in the group and it sends a clear message that everyone, including the facilitators, will be learning from one another.

“Grounded in practice-based evidence, our approach privileges people’s local knowledge with an emphasis on abilities rather than deficits, possibilities rather than limitations and what is strong rather than what is wrong in people.”

– Journal of Systemic Therapies/Narrative and Brief

Learning Objectives

Participants will:

- Listen to different perspectives on the topic being discussed.

- Critically reflect on the way culture impacts communication and values.

Activity Directions

Set-Up: Chairs in a horseshoe with five chairs at the front of the horseshoe for a panel discussion.

- Identify and invite panel members: Before this activity starts, invite four people from diverse backgrounds to be on the panel. Tell them that you will be asking them questions about what support and helping look like in their culture. (Or, you may have a different question depending on the nature of your workshop).

- Design relevant questions: Facilitator designs questions ahead of time that will help the panelists to share their values and perceptions.

- Introduce purpose of panel: Facilitator opens the activity with genuine curiosity about the world views of the panelists. In the case-study below, the facilitators were both Canadian and the participants were from 7 different countries. The facilitator opened with the following statement:

“Over the next few days we are going to be exploring communication skills and different ways of supporting people in distress. However, both of the facilitators are Canadian and were trained in Western modalities. We do not want to impose our world view or make assumptions about what will work in your cultures and communities. We hope that approaches we explore might add something to your tool box of interpersonal skills, but in the end you need to decide if these approaches fit for you and your contexts. With the panelists in front of you, we will explore what helping and support look like in their communities and then we will turn to you, the rest of the group, to find out how their ideas resonated with your own cultures, experiences and values.”

Key Points

- We are your facilitators, but we don’t have all the answers.

- We want to learn from you too and need you to tell us when our approaches don’t work for you.

- Cultural values influence communication patterns and we can explore together if there are some elements that seem universal.

4. Interview panelists: Facilitator asks panelists individual questions about their culture, experiences and values.

Sample Questions:

- What did helping and support look like in your family or community when you were growing up?

- How would you know if someone was distressed or needed emotional support?

- Who do people usually turn to if they are having difficulties?

- How is mental health viewed or treated in your community?

- What is it like for you or your friends to seek help if you need it?

- What is your culture’s history with colonialism and how has that impacted social support?

- How is emotional support different depending on gender and/or sexual orientation?

- Are there any other social, cultural or political dynamics that shape your experience of asking for or receiving emotional support?

- Is there anything else you would like to tell us about your community and how it copes with challenges?

5. Summarize: The facilitator summarizes the themes and find ways for the conversations to weave in and out of each other as opposed to just going down the line with each question.

6. Ask for responses from outsider witnesses: After about 15-20 minutes the facilitator tells the panelists that they can take a rest and they turn to the bigger group to ask which things resonated for them from the panelists discussion. The facilitator continues to paraphrase ideas and feelings.

7. Final reflections from panelists: After 5-10 minutes, the facilitator turns back to the panelists and asks if they have any final thoughts, reflections or things that they would like us to know about their values or culture.

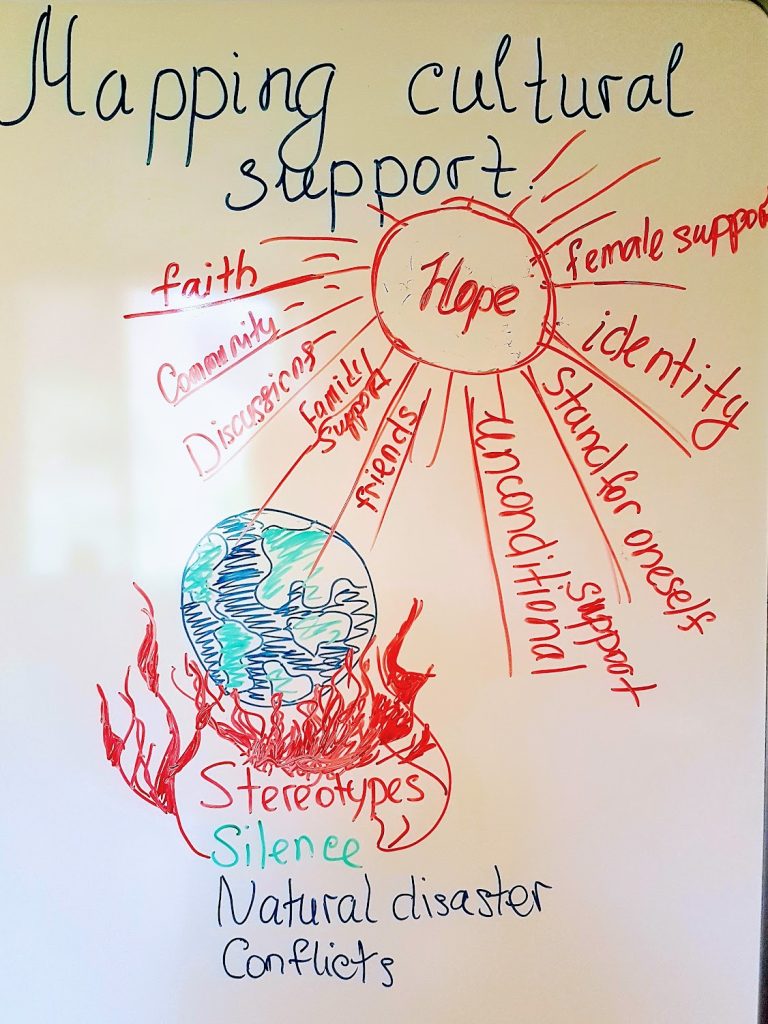

8. Capture the themes: While the facilitator is interviewing the panelists, have two participants or assistants document the responses with graphic facilitation (words and images).

Case Study: Summer Institute, University of Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan

The discussion about support and helping relationships generated rich data and helped us understand the participants in our learning group. Together we learned that:

- Many of our participants came from post-Soviet cultures and some of them had grown up in communities where there was a high degree of secrecy because there was worry that informants could tell the KGB about people’s behaviors or opinions. This still impacts a sense of trust and reaching out for help.

- In Kyrgyzstan, many people turn to nature by returning to their family herding pasture, to restore themselves and heal if there have been physical or emotional challenges.

- Counselling and psychotherapy was relatively uncommon in most communities, schools and universities, so it is not very usual to turn to experts for help.

- Family, elders and religious leaders often played the role of mentors, counsellors and mediators in many communities.

- Some people talked about suicide as being a problem in their communities, but also said that there is often great shame so suicide is hidden and not talked about.

- Some people came from places where there had been many natural disasters and they saw their communities come together with skilled practical and emotional support helping people deal with the catastrophes.

- Psychologists and counsellors in some countries are perceived to be more like doctors who have expert medical knowledge.

- In many communities, including Western ones, men find it harder to talk about mental health or ask for help when needed.

Observation:

“Mapping the Terrain” is a powerful exercise for creating a community of co-learners. Often facilitators have education and privilege that lead participants to undervalue their own innate skills, insights and wisdom. This activity brings to the surface the cultural, social and historical currents that shape the eco-system of the group. As the facilitator respectfully explores the underlying stories and values of participants, they are also modelling an ethos of curiosity, openness and acceptance.

It is important for facilitators to explore their own “social location” and how that positioning impacts their personal assumptions and how they are perceived by participants:

The term social location is often used by facilitators working in the anti-violence sector (Baker et al, 2015; Ontario Association of Interval and Transition Houses, 2018; Simpson, 2009). The concept of social location comes from the field of sociology and describes the groups that people belong to because of their place or position in society. An individual’s social location is a combination of categories, factors, or attributes such as gender, race, age, ability, immigration status, language, sexual orientation, employment, and religion. All of these elements are constantly interacting which makes social location unique to each individual (Ontario Association of Interval and Transition Houses, 2018).