He Rourou, Volume 1, Issue 1, 49-66, 2021

Tim McVicar

Abstract

This project employed an iterative research approach to examine the effects of a critical pedagogy of place (Milne, 2016; Gordon, 2018; Gruenewald, 2013; Penetito, 2018) on Pākehā learners in a Level 1 English class in Northland, New Zealand. The project tracked Pākehā learners’ engagement and achievement outcomes and examined if there were notable shifts in their perspectives about Māori inequality in Northland as a result of the project.

The project results showed that a critical pedagogy of place was initially confronting for Pākehā learners, and participants displayed low engagement in the project’s early stages. However, by the end of the project, Pākehā learners began to articulate more nuanced and constructive understandings of the effects of the Northern wars, colonisation, institutional discrimination, and inequality faced by Māori. A marked increase in engagement was evidenced, and final assessment results in the standard were notably high.

A critical pedagogy of place, in this sense, was ‘consciousness-raising.’ Participants’ formal writing outputs, as well as small group interviews at the project’s conclusion, showed increased empathy to Māori concerns within their communities. These positive outcomes depict how schools can legitimise and offer safe spaces to analyse challenging aspects of New Zealand’s past and present.

Introduction

This project analysed the inclusion of a critical pedagogy of place (Gordon, 2018; Gruenewald, 2013; Milne, 2016; Penetito, 2018) to teaching and learning within the context of an NCEA Level 1 English class at a Northland Public High School. The project involved implementing a five-week teaching unit that explored the Northern Land Wars, particularly the battles of Kororāreka and Ruapekapeka, as platforms for investigations into imperial motivations, colonial legacies, iwi (tribe) and hapū (sub-tribe) responses to these wars and the impact such histories have on cultural identity presently. The project tracked Pākehā (New Zealander of European descent) learners’ engagement and assessment results and examined if the content provoked dispositional changes in their understandings. AS90053, 1.5 Produce Formal Writing is the aligned assessment standard.

The school where the study was undertaken recognises the centrality of the bicultural dynamic in community and school life in Northland and instructs teachers to “actively nurture te reo Māori (Māori language) including local dialect te reo o Ngāpuhi, tikanga (Māori customary practices, values and behaviours) and our bicultural heritage.” School kaumātua (elders), whānau (families), senior leaders, teachers and learners agree that the school needs to develop authentic learning environments for Māori learners. Like many mainstream schools in New Zealand, the school seeks insight from Māori-medium education pathways which continue to deliver exceptional results for many Māori learners because progressive pedagogies such as critical pedagogy can thrive in such an ethnically homogeneous environment. Indeed, it is often research and experiences in these contexts that inform national policy about what works and what does not for Māori learners, even though the majority of Māori learners remain in mainstream settings. Yet, this is perhaps where contemporary critical pedagogy in New Zealand falls short: it empowers minority voices to challenge social injustices in society but without engagement, exposure and critical reflection from members of the dominant culture themselves. Surprisingly, little research on how such pedagogies would work within mainstream bicultural schools in New Zealand has been undertaken. Potentially, the large number of learners from the dominant culture complicates the introduction of critical pedagogies, and it is this potential complication that this project seeks to examine.

Within Te Tai Tokerau (Northland) English departments, authenticating indigenous perspectives necessitates implementing content and curriculum that faithfully reflects and incorporates Te Tai Tokerau Māori worldviews, histories and knowledge. The English curriculum at the school where the project was undertaken may be enriched if its teachers develop units that foster critical approaches and encourage learners to question and challenge ideologies, beliefs, and value systems that dominate within a society and perpetuate injustices and inequalities. This could involve the localisation of social justice themes through the study of texts embedded in and about the places that learners are from. This would ensure that the learner is at the centre of their learning and encourage them to consider the social-cultural and political forces that impinge on their lives, not indirectly but directly.

Exposing Pākehā learners to such content supports those from the dominant culture to engage with and respond to non-dominant perspectives. Learners rather naturally avoid addressing subjects that may force reflections on their place in society. In my teaching experience, this is the same for Māori learners as it is for Pākehā. While non-Māori learners tend to have a surface understanding of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, they often remain unaware of the contested and complex interactions between Māori and Māori, Māori and the Settler Government, and Pākehā and Māori. Yet, learners cannot understand the lingering effects of systemic inequality without exploring the impacts of colonisation on indigenous Māori. As O’Malley (2019) states, “Any discussion of contemporary Māori poverty that fails to acknowledge the long history of invasion, dispossession and confiscation is missing a vital part of the story” (para. 8). While this can be confronting for Pākehā learners, such knowledge and the empathy it produces is becoming increasingly essential.

Literature Review

David Gruenewald (2003) has linked the theoretical strands of critical pedagogy and place-based education. Understanding his synthesis and its relevance to English classrooms at the Northland school necessitates an overview of the two discourses.

Critical Pedagogy

Developed by Paolo Freire (1972), a critical pedagogy of education places the raising of learners’ critical understanding at the heart of education. The goal of education, Freire – and later theorists such as bell hooks (1994), Ira Shor (1992), and Henry Giroux (2011) – asserts, is not simply the transfer of knowledge to support learners’ economic opportunities, instead, the goal of education is to raise learners’ critical consciousness through an understanding of the social-political forces at play within societies so that the learner, the learning environment and society as a whole can be transformed. As an influential theorist, Peter McLaren states:

Critical pedagogy is a way of thinking about, negotiating, and transforming the relationship among classroom teaching, the production of knowledge, the institutional structure of the school, and the social and material relations of the wider community, society, and nation-state. (McLaren, 1998, p. 45)

The need to transform education, and through it, broader society is fundamental to critical pedagogy. Theorists contend that in many countries, the dominant social-political power structures are the products of an ongoing colonial-capitalist framework that normalised control over indigenous populations and embedded the racial-cultural superiority of the colonisers. Disrupting the global monoculture of neoliberal economics and decolonising the institutions that perpetuate cultural narratives that concentrate power and privilege within a dominant group and exclude nondominant voices, worldviews, or alternatives is at the heart of critical pedagogy (Gruenewald, 2013). The aim is to critique, disrupt and remove the social, political, economic and cultural norms that ‘oppress’ non-dominant groups so that societies become more equitable.

Place-Based Education

The other important strand is place-based education (PBE). A key component of PBE is the application of learning to real-life situations. PBE contends that a school’s location is a springboard. However, questions remain over a perceived disconnect between the mediated and constructed experience of school education and the embodied immersive experience of the learners’ real lives. PBE often has an overt environmental concern, and like critical pedagogy, PBE is a reaction to globalisation and the neo-liberal economic homogenisation of contemporary schooling and culture. The effect is “social disintegration occurs as basic connections to the land fray and communities become less resilient and less able to deal with the dislocations that globalization and ecological deterioration bring about. A community’s health— human and more-than-human—suffers” (Sobel, 2004, p. 3).

A Critical Pedagogy of Place

Gruenewald believes that as independent discourses, both critical pedagogy and place-based education have shortcomings. He contends that PBE tends to focus on the ecological dimension of place without a necessary focus on the social relationships that make up physical spaces. On the other hand, critical pedagogy often “betrays a sweeping disinterest in the fact that human culture has been, is, and always will be nested in ecological systems” (Gruenewald, 2013, p. 3). Without grounding in particular places, critical pedagogies remain too focused on the macro-level of society and general forces of oppression than to those attuned to the immediate environments that learners live in:

Place, in other words, foregrounds a narrative of local and regional politics that is attuned to the particularities of where people actually live, and that is connected to global development trends that impact local places… Place-based pedagogies are needed so that the education of citizens might have some direct bearing on the wellbeing of the social and ecological places people actually inhabit. (Gruenewald, 2003, p.3)

Bowers (2008) provided an important amendment to Gruenewald’s earlier position. He argues that Gruenewald ignores the cultural commons shared between people from different ethnicities within a place. Different cultural groups within a place have often reached a cultural consensus and share cultural legacies. He believes that not everything needs to be decolonised and transformed. Not all change is positive, and some knowledge should be preserved:

Gruenewald does not acknowledge that conserving involves, among other things, an awareness of the ecological importance of the many forms of intergenerational knowledge, skills and patterns of interdependence and support that can also be understood as traditions. (Bowers, 2008, p. 328)

According to Bowers, rehabilitation and decolonisation must work together for the betterment of all members of a society and construct an authentic critical pedagogy of place where thick descriptions (Geertz, 1973) of cultural places and histories can lead to greater empathy, consensus and awareness of other cultural groups that make up spaces. Unlike critical pedagogy, it allows individuals and groups to construct their own narratives about the world they live in and how they are affected by it. Thus, a reformed critical pedagogy of place aims to “(a) identify, recover, and create material spaces and places that teach us how to live well in our total environments (reinhabitation); and (b) identify and change ways of thinking that injure and exploit other people and places (decolonization)” (Gruenewald, 2003, p. 9).

As a general philosophical framework, a critical pedagogy of place that promotes rehabilitation, decolonisation and equality is relevant to the bicultural context of this study. Significantly, it avoids an exclusivist focus on decolonising education and de-legitimising the lived experiences of non-Māori groups. Rather it supports the recovery of shared histories and encourages learners to appreciate the complexity and legitimacy of their own culture.

Applying a Critical Pedagogy of Place

Critical pedagogy and place-based education have been explored within educational spaces in New Zealand. Ann Milne (2013; 2016) has explored how critical pedagogy can address shortcomings in the New Zealand schooling system. She (2016) claims that the neo-liberal capitalist framework has negatively impacted education systems and created a push for globalised sameness. As a result, indigenous learners remain alienated because their norms and values are different from the dominant culture. Milne contends that mainstream schools in New Zealand are, in fact, “whitestream schools”. She believes schools project value judgements about whose knowledge counts in a system that “damages Māori and Pacific learners” (Milne, 2013, p. 4). Milne uses the metaphor of a colouring book to describe the experience of Māori and Pasifika learners within mainstream schools. This colouring book is not blank but is ubiquitously white. To enter such schools, Māori and Pasifika learners are required to leave their identities at the door. Thus, “Not only is the background uniformly white, the lines on the page dictate where the colour is allowed to go” (Milne, 2013, p. 1). In such an educational context, it is obvious why Pākehā learners are more successful. She champions a critical curriculum that empowers Māori and Pasifika learners to contest the forces that marginalise them.

If we are serious about providing authentic spaces in our schools for indigenous and minority ethnic groups, we have to ask the hard questions about the purpose of schools, whose knowledge counts, who decides on literacy and numeracy as the primary indicator of achievement and success? We have to name racism, prejudice, stereotyping, deficit thinking, policy and decision-making, power, curriculum, funding, community, school structure, timetabling, choice, equity instead of equality, enrolment procedures, disciplinary processes, poverty, and social justice. We have to eliminate these white spaces and mitigate the damage they have caused (Milne, 2016, p. 4).

Milne’s research is an important critique of the New Zealand education system. She highlights the need for the decolonisation of schools if there is any chance of educational equity. However, questions remain: Milne, like many critical theorists before her, does not present a framework for how decolonisation can occur within whitestream schools themselves – nor does she present ways to navigate this decolonisation so that members of the dominant culture can navigate it and remain supportive. Instead, her solution is a panacea to the problem by promoting a differentiated curriculum for Māori and Pacific learners and, by extension, the assumption that indigenous/minority learners need separate schools. Milne faces the criticism expressed by Bowers that rehabilitation is as vital as decolonisation:

[A teacher should not] set out to decolonize or emancipate students from the intergenerational knowledge and skills that the critical pedagogy theorist has relegated to the realm of silence or has prejudged as backward. (Bowers, 2008, p. 332)

Certainly, within the context of an English classroom with a bicultural composition of its learners, Milne’s critical pedagogy would struggle to gain traction. Such contexts are complex and necessitate continual negotiations and empathy between learners and whānau from dominant and indigenous cultures. As Bowers points out, thick descriptions of such a learning space would highlight the organic overlapping of identities within larger ethnic identities. While her approach can help shape the critical questions asked, a more nuanced approach is needed.

Wally Penetito (2008) may provide such an approach. Penetito provides an important element missing in Milne’s writings. He articulates a perspective that more closely fits a critical pedagogy of place adapted for the English classroom. He contends that the principles and practices of place-based education should be adopted by all compulsory schools in New Zealand. PBE is not just for non-Pākehā learners but has relevance to all learners. Echoing a critical perspective, Penetito notes that PBE should investigate questions that are often ignored or disregarded because of the normative educational focus on what works for the mainstream and a subsidiary focus on how indigenous schools compare to the mainstream. Indeed, Milne’s approach can be read as an example of the latter, while Penetito’s PBE strives for the establishment of critical consciousness in all New Zealand learners. Penetito contends that PBE is not an indigenous alternative, rather it satisfies “indigenous people’s aspirations as a priority, but in every case, the objectives and strategies recommended are of benefit to everyone” (Penetito, 2008, p. 6). Like Milne, he sees the need for an education that reacts against the homogenisation of culture and detachment from place through globalising economic forces. He notes that you have to get people to think about changing something: the invisible needs to be made visible. As Gruenewald, Milne, and others above have noted, one way to make something visible is to subtract or interrupt it.

One of the most important characteristics of Penetito’s PBE is the expectation of its enriching nature, which is in contrast to the often-confrontational modus operandi of critical pedagogy. Penetito hopes that learners develop a love of and a sense of responsibility for the places they inhabit, regardless of ethnicity. PBE attempts to instil an awareness in learners about how people have and continue to respond to the places that the learner resides. Following Gruenewald’s critical pedagogy of place, as amended by Bowers, it is as much about the rehabilitation of identities as it is about their decolonisation. PBE is relevant to all learners because it strives to answer two fundamental questions: “What is this place?” and “What is our relationship to it?” (Penetito, 2008. p. 5)

Penetito’s framework encourages curriculums within English departments that motivate learners to explore and reflect on the places and histories that shape them. Penetito documents how a critical pedagogy of place could be adopted throughout mainstream schools. The next important step is to see how such a framework plays out at the chalkface.

Research Questions and Aims

The guiding research question for this project was: How does a critical pedagogy of place-based approach to teaching English affect assessment outcomes and lead to dispositional changes in Pākehā learners?

The aim was to see how learners from a class of primarily Pākehā learners engaged with and reflected on critical perspectives about Māori-Pākehā relationships in New Zealand. Sub questions included:

- How is Pākehā engagement affected by an English Unit focussed on the critical questions about power, race, inequality and privilege in New Zealand?

- Does a critical pedagogy of place change learners’ perception of Pākehā/Māori relations?

- Is there any quantitative influence – negative or positive – on assessment results for Pākehā learners when bicultural identity is examined through the lens of a critical pedagogy of place?

Participants

Data for this project were derived from 20 participants from a co-educational Level 1 English class in a Northland High School. According to Kamar learner records: seven participants were female; 13 were male. Five learners were Māori (four female, one male) of Ngāpuhi descent. One male learner was of Korean descent, while another male learner was of mixed Pākehā-Japanese descent.

The remainder of the participants were of Pākehā descent; most were male (ten males; three females). The class was intentionally chosen because of the high level of Pākehā learners in the class.

Methodology: Action Research

The methodology employed for the collection and analysis of data is action research. This spiral of inquiry methodology frames how data has been collected and analysed. Crucially, action research binds teaching and research to the location and people involved in analysis, a perspective supported by a critical pedagogy of place.

Action research is an evidence-based approach developed to overcome artificial distinctions between pure research and pure practise (action). Action research sees practice and research as intimately linked (Ferrance, 2000). Researchers are often practitioners themselves, who address and seek to resolve issues and challenges they experience in their context (Ferrance, 2000). A focus on practice in situ is the theoretical backbone of the action research process of inquiry. Action research readily aligns with a critical pedagogy of place as both aim to transform the classroom space.

An integral feature of action research is that researchers are expected to engage in self-reflective inquiry to strengthen learner outcomes and maximise social justice within their sphere of influence (Ferrance, 2000). Thus, action research aligns with a critical pedagogy of place because it is a reflective undertaking that involves experimentation with different content and classroom procedures, reflection on success and challenges, and the cyclic refining of practice in the pursuit of educational achievement and equality for learners.

Because action research encourages analysis of my responses and reflections as part of the inquiry process, it places my narrative experiences within the interpretation of data, authenticating the learning journey that I shared with my learners. This project is one cycle of inquiry amongst many more to follow as I develop as an authentically biculturally responsive practitioner. Importantly, this project is not intended as a standalone piece of research. To be meaningful for my practice and learners, it necessitates multiple iterations and spirals of inquiry to produce the best results for learners.

The project began in week 6 of term 2, 2020; a week after school reopened due to COVID-19. The course ran for five weeks, with time given in the sixth week for learners to finalise their writings. At the beginning of the project, before any content was delivered, learners were given an anonymous survey to complete – this tracked their pre-exposure perspectives and understanding. In the second week, as part of content study on implicit bias and institutional discrimination, participants completed an Implicit Association (IA) test). This was used as platform to address the complexity of how bias works and to prompt reactions in relation to their own potential bias. After three more weeks of content delivery and classroom activities, learners began to write up their own research papers for submission as part of the assessment in week 11 of the term. Final small-group discussion occurred in week 12, after the completion of the course.

Data Collection and Analysis

The sample size of this project is small. This fact, combined with the target research questions, meant that data collection and analysis was mixed involving both quantitative and qualitative analysis. Because I tracked dispositional changes, I have compared and contrasted data sets from the beginning of the project and those at the end of the project. Information was gathered from participants via the following:

- anonymous response to a Google Form;

- small-group interviews;

- reflective writings on class content;

- formal writing outputs.

The combination of anonymous, reflective, peer-mediated, and formal responses provided a solid foundation to answer the research question. The range of data collection tools was intentional because what learners stated in a given context was influenced by who can hear/read what they say. As expected, participants gave different answers depending on context and tool. For example, formal writing outputs were developed over time, in contrast to other data tools which encourage spontaneous answers.

The study did not track individual learners. This was because participants were told perception survey responses were anonymous and so that individuals felt safe to offer their opinions. Furthermore, the research questions only required analysis of responses about participants’ ethnicity. Accordingly, participants’ responses are analysed according to ethnic identity only.

Survey and interview questions were intentionally open-ended, encouraging learners to respond to them as they interpreted them. Indeed, the interpretative nature of survey questions provided interesting results in themselves. For example, several learners interpreted “place” to refer to the house and immediate neighbourhood rather than a wider geographical area. Often these interpretations were as important as the answer to the question itself.

The small sample size made considerations of quantitative changes in perspectives less meaningful. However, with data sets compiled by ethnic groups, it was possible to make general comparisons based on shifts in what proportion of the class responded in a given way. Where possible, data was categorised in relation to similar ideas/themes. To mitigate bias in the data analysis, a project collaborator supported the coding of responses. A positive response was given if the respondent gave an empathetic answer to a question and a negative for a dismissive response.

Formal writing outputs were submitted as part of an assessment from which the learners would receive four NCEA credits. The formal writing output was an opinion piece on the question: Equality in New Zealand: Fact or Fiction? This output provided significant data because it allowed learners to write a considered response to the themes covered in the unit.

Discussion groups were composed of learners who usually sit together as this offered a comfortable setting for ideas to be expressed. These discussions captured learners’ statements amongst their peer group and encouraged extended discussion and reflection on target questions. Questions targeted perceptions of course content and if this knowledge had changed their perceptions about social inequality in New Zealand. Another tool that I used was a journal of my reflections during the project. Action research and critical pedagogy highlight that the researcher is part of what is being researched. To this end, reflecting on and modifying the project was integral to providing detailed evidence to answer research questions.

Findings: ‘Consciousness-Raising’ Results?

To provide the most robust data set to analyse the research question, I will compare and contrast “formative” participant data and statements with “summative” participant responses at the end of the project as overviewed in the data collection and analysis section.

Formative Findings

Learner Perception Survey

A learner perception survey was created specifically for this project and titled The Identity Survey. This was completed by participants before the introduction of the content on day one of term three. The survey encouraged participants to respond to nine open-ended questions about ethnicity, ancestry, the New Zealand land wars, Māori culture and perceived ethnic privileges and inequality in New Zealand.

Participants were advised that their responses would be anonymous but may be read in a public space or by the school’s new principal. I emphasised that the results could be shared publicly to encourage participants not to give answers they perceive I as the researcher and their teacher would want and also to consider the language they used to express themselves.

For clarity in analysis, while individual expressions in such a small pool of participants should not be seen as necessarily indicative of general group perceptions, meaningful data can be extracted if participants are grouped and analysed as ‘Pākehā’ (21 participants), and ‘Māori/Māori-Pākehā.’ (seven participants) Analysis of gender is beyond the scope of this initial survey.

Due to space constraints, I will only discuss two questions though these are not representative. For example, both Pākehā and Māori gave nuanced answers about their own family histories and the relevance of ethnicity to identity. Below I focus on questions that drew the most confronting responses. Two questions targeted perceptions of discrimination and privilege based on the participant’s ethnicity. Two Māori participants stated they were unsure —the remaining five perceived discrimination against Māori. Only one Māori participant stated that Māori have some privileges. Māori perceptions of disadvantages included: “Automatically being portrayed as a criminal, hard to get jobs when they see you have a Māori name” and “People believe we are all the same people and we are all bad.”

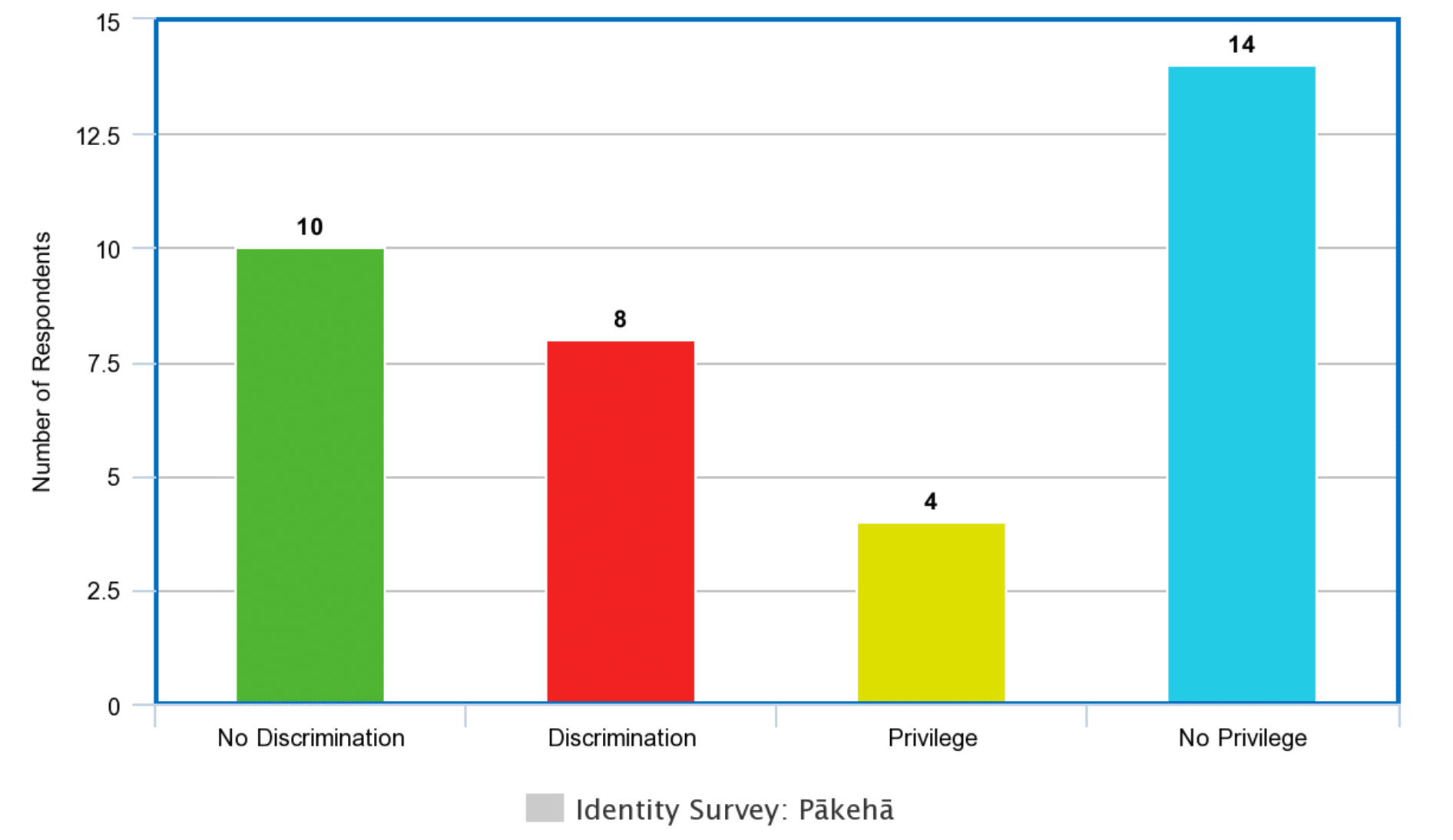

As Figure 1 depicts, Pākehā respondents were split relatively evenly on whether they believed they faced discrimination based on ethnicity. Examples of discrimination for Pākehā included “Maori-only teams and courses” and the expectation to “Work hard and get jobs and pay tax while they [Māori] just sit in OT [occupational therapy] living off the dole smoking dope.” The survey highlighted that most Pākehā participants do not believe that Pākehā have privileges over other ethnic groups. Rejecting privilege, two participants responded: “Everyone is equal.” Participants that thought they had privilege stated: “I probably do have some privileges since I’m white and not homeless and all that”, and another “We are treated better by the police.” Two respondents answered “probably” without further detail.

The question “Who was involved in the NZ Wars and what were they about?” drew varied responses. Four Pākehā and two Māori respondents stated that they did not know. Māori that provided answers noted that Māori tribes and colonial forces fought over land. One said that the wars “Were all about claiming land but ultimately came to an agreement to live in peace together.”

Most Pākehā similarly noted the wars were between the Colonial Government and Māori, and some identified that they involved land disputes, without reference to the Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Responses by Pākehā included: “our ancestors”; “New Zealanders and the British over land” and “The British Government and the Māoris”. Two Pākehā respondents expressed overtly negative statements that referred to the superiority of British force/culture over Māori. These statements will not be repeated here, but it is essential in the context of this project that it is noted that such perceptions exist in the participants and that they are willing to write these down without reflection on a wider audience. Significantly, most learners have already spent two years at the school, and this dispositional mindset in some of the students has yet to be addressed. While it is clear that these perspectives are not supported by the ethos of the school, it highlights that more needs to be done to challenge such views.

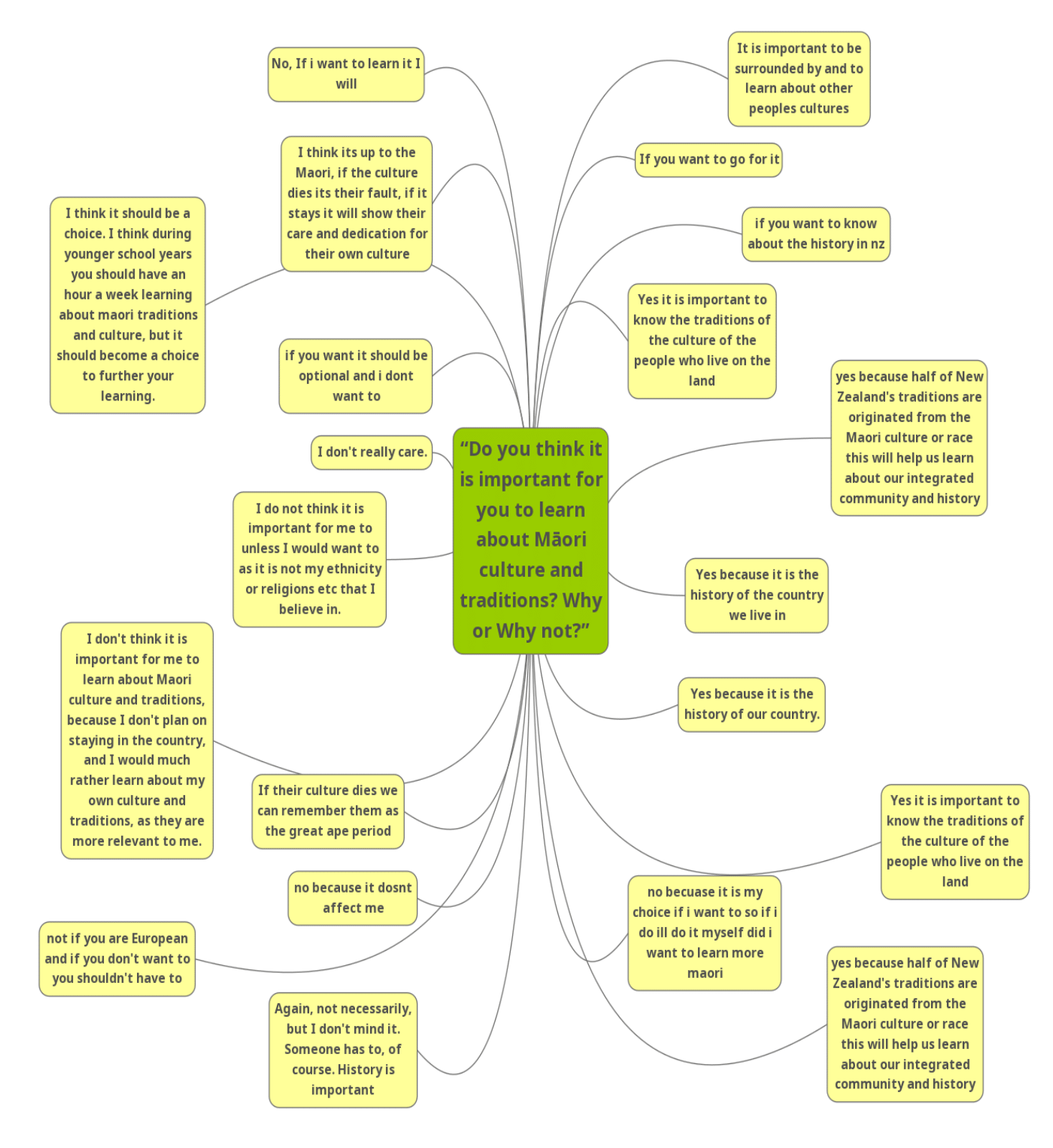

Participants were also asked “Do you think it is important for you to learn about Māori culture and traditions? Why or Why not?” Māori respondents were unanimously in support. Reasons given included to ensure cultural survival, because it is a part of their identity and to understand New Zealand history: “Yes, as a citizen of New Zealand I believe it is important to learn about the culture of my country”; “Because it is a New Zealand culture and everyone in New Zealand should know about Māori!!!!! Because that is this country’s NATIVE CULTURE and the culture and traditions DIED because of this fucked up white system.” Pākehā responses are displayed in Figure 2 and note a split between participants about the relevance of learning about Māori culture. Like a few Māori participants, some appear to have interpreted the question to refer to whether learning about Māori culture should be compulsory in schools. Again, the results highlight that some believe it is not relevant to those who see it as very important. Furthermore, some responses were overtly racist.

Implicit Association Test Response

The second formative activity used a critical pedagogical approach by getting learners to take Harvard University’s race-based Implicit Association Test (IAT) (Greenwald et al., 1998) to explore their own implicit beliefs and attitudes. The IAT tracks automatic associations between concepts (African American children/European children) and evaluations (good/ bad). The test tracks if participants display a disparity between explicitly stated associations and associations they may hold subconsciously. According to the test, the quicker a participant’s responses, the more likely an association between a concept and an evaluation is. Responses are scored ‘no preference’, ‘slight’, ‘moderate’ or ‘strong’. Unlike the survey, this response would not be anonymous. Before taking the test, a discussion was held in class about the test, what it tracks and potential issues with the test’s design.

An analysis of the responses provides some valuable data. All learners present in the class completed the test and the written response sheet. All learners answered correctly to the control question, which required them to define what an implicit bias was. Learners were then asked to comment on their results from the IAT. Sharing their results was optional, and some abstained. The two learners of Asian descent noted that no preference was recorded between African American children over European children. Two Pākehā learners recorded a preference for African American children. One Pākehā noted a strong preference for European children and found it unsurprising. Of the two Māori learners that provided comments: one reported a slight bias towards European children, and the other that the test said they had no preference.

Several Pākehā learners were alarmed with their results which showed a slight to moderate automatic preference for European American children compared to African American children: “It kind of surprised me because I don’t think I prefer anyone” and “I slightly prefer white people, I think that this happened because I was delayed when categorising black people because I wanted to categorise them correctly.” Many blamed the test itself: “I don’t understand how the test actually proves an implicit bias when the test is based on pressing keys.” It was clear from the test that some Pākehā participants felt confronted by their test results and challenged the validity of the findings.

Summative Findings

Assessment results

While enhanced social justice awareness is difficult to track, assessment results are not. The project answers the sub-question about assessment outcomes for Pākehā learners engaged in a critical pedagogy of place. All 20 participants achieved formal writing credits for the assessment. Six participants produced writing at Excellence level; another seven at Merit and six at Achieved. Results for female Māori participants showed stability with previous results with two Merits and two Achieved. The one Māori male participant received his first Merit in the class. Like Māori females, the assessment results for Pākehā females were strong, with two Excellence responses and one Merit and consistent with previous assessments’ results.

The most significant increase in achievement results was for Pākehā males, evidenced by a comparison of results for a relatively comparable assessment “1.11 Close Viewing”. Four learners received the same grade for both assessments. Two received a lower grade for formal writing than for Close Viewing. However, one of the results was an anomaly; the learner was marked down because of a sentence structuring error that restricted them from receiving higher marks despite strong content. For five participants, their results improved, with three learners moving from a Merit in Close Viewing to an Excellence grade for Formal Writing. Two other participants went from an Achieved in their Close Viewing essay to a Merit in their formal writing. All learners who focused on ethnicity – bar one with a sentence structuring issue – received the same or higher grades in the previous assessment.

These results are significant. They answer one of the project’s key research questions. They show quite clearly in the accessible currency of assessment results that members from a society’s dominant culture and gender are not adversely affected academically when compelled to examine the structures of privilege and historical forces that account for their status in society. For some participants, their results improved through independent research and reflection. It is also significant that only one Pākehā male participant used the opportunity to counter a defence of males concerning the gender pay gap. Pākehā that felt uncomfortable and/or disinterested in the topic, did not suffer academically due to the Unit focus.

Formal Writing Outputs

All learners submitted persuasive writing pieces and passed the assessment. All wrote on topics of discrimination and inequality in New Zealand. The guiding question that participants were given as an essay prompt was: “Equality in New Zealand: Fact or Fiction?” Learners needed to choose one area where equality/inequality may be present to focus their writing. While issues between ethnicities in New Zealand were the basis of the course as demanded by a critical pedagogy of place, learners could make their own choices about the topics they wrote on.

In line with the literature on the efficacy of critical pedagogy for indigenous learners (Milne etc.), all Māori participants (four female, one male) wrote about the evidence for, causes of and solutions to Māori inequality in New Zealand. Seven non-Māori male participants also chose to write on this issue, with three Pākehā self-selecting an examination of pre-Treaty relations in New Zealand.

Following a trend I have seen in a previous class where I have trialled critical pedagogy, Pākehā female participants (n=3) were the least likely to write about ethnic issues. Pākehā female social justice focuses included the gender pay gap, abortion legalisation and discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community. In contrast, for Māori females, ethnic issues appear to dominate gender concerns even if they are closely interrelated. As with males from the dominant cultural group, Pākehā females’ examinations of the effects of their own culture on others is challenging. Another reason was possibly that the course did not present a strong female Pākehā voice on the issue, compared to the many Pākehā male voices who wrote and presented texts.

The remaining participants chose not to examine ethnic and cultural inequality directly. One male Pākehā learner wrote a piece arguing that the gender pay gap is not a significant issue and not an example of inequality between men and women. He was the only participant to write a defensive piece of writing. Another participant examined economic inequality in New Zealand, focusing on population growth, wage rates and house prices. Learners used evidence for this inequality from numerous statistical sources, as compiled in a news article. It was notable that when discussing the causes for these inequalities, all Pākehā learners referred to structural/institutional discrimination/racism as a leading cause of Māori inequality. One learner referred to the marginalising strategy of the early settler government.

While participants were adept at finding and evaluating evidence, presenting solutions to the problem proved more difficult, and two found the solutions they researched as implausible. Of the seven Pākehā learners that addressed Māori social disadvantage, all noted it was a significant problem; five were optimistic that it could be reduced in the future, while two were sceptical it could be resolved in the short term because of generational inequalities and discrimination. Two participants referred to the need for greater equity for Māori, a topic covered in class, while two learners argued that equity is not going to overcome prejudice and that it may cause a backlash by Pākehā, who see it as unfair. One participant referred to the need to teach tolerance to young people.

The three learners who examined relationships before and after the Treaty relied on evidence from “NZ history” and “Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand”. One learner’s thesis statement was “I strongly believe that the relationship was positive at the arrival of Pākehā and then turned negative once the Pākehā tried to evolve New Zealand.” Two respondents noted that the relationship was poor and worsened because of the Treaty. All three believed the relationship between Māori and Pākehā is still problematic and that solutions are required, such as compensation for land. One participant, who self-identified as making racist comments in the initial survey, argued that while there is a clear social disadvantage for Māori, he believes that there is too much focus on supporting Māori over other people in New Zealand.

Small-Group Discussions

In the first week of term 4, interviews were conducted with two small groups of Pākehā participants. They were asked to reflect on the project content, what they learned, their assessment results and whether or not they have a greater understanding of inequalities in New Zealand. Because I expected that some participants would dominate the discussions, I encouraged them to write down their answers before the discussion. This was to prime them and ensure that participants’ answers were not swayed as a result of the opinions of others. The participants’ responses confirmed the positions they had developed in their formal writing. One participant stated that his perspective had changed because he “did not know the reason for the bad relationship between Māori and Pākehā was because of the past actions of Pākehā.” The remaining Pākehā males agreed with him, with one noting, “I definitely have a better understanding of the problems this country faces.” However, one participant was an outlier. He insisted that his perspective did not change because “everything was done for a reason” and that it “should remain a choice for learners whether or not to learn about Māori culture.”

The three Pākehā females were specifically asked why they chose not to focus on ethnicity. One participant noted that there had already been a lot of focus on race in English throughout the year, and she wanted to do something different. Another participant said she chose her topic because it was something that she is extremely passionate about as she is a member of the LGBTQ+ community and directly affected by social discrimination. None of the participants in the small-group discussions noted any discomfort with the topic. However, it must be recalled that there was some discomfort in the larger participant pool.

Analysis of Summative Findings

The summative data for most Pākehā males, especially in relation to their formative data, show that a critical pedagogy of place achieves its social justice aspirations of raising consciousness and encouraging a greater understanding of significant social-political issues in their society. Assessment results remain strong, and the depth in which the learners engaged with their chosen topics shows the efficacy of critical pedagogy. The depth of analysis and independent research that the learners undertook highlights that the participants believed that the theme and topics were meaningful to them and deserved investigation. As the writings of one participant highlight, this investigation process is not easy. Bowers (2008) reminds us Pākehā need not reject their own cultural identities and histories to acknowledge that inequality is a problem that needs to be addressed in their society. By adapting the theoretical framework outlined by Penetito to suit a bicultural English classroom in a mainstream school, the research showed that members of the dominant culture can directly address issues of power and privilege within their communities and not become alienated as a result. A critical pedagogy of place therefore meaningful and relevant to all New Zealand learners.

Further analysis and research are required to investigate how female Pākehā can be encouraged to explore this topic and for those who feel confronted by the topic to be guided through their initial strong reactions into a place where they are comfortable to address the topic, hopefully resulting in a reduction of ILPs and greater uptake of learners willing to participate.

Limitations of Study and Next Steps

Iterations of this teaching unit would include changes. Future teaching units would be much more collaborative and run concurrently or with support from other departments in the school. This could consist of the curriculum standard of formal writing aligning with an assessment standard in another department to broaden the scope of the learning. Broadening the diversity of voices heard in the literature presented to the learners would also significantly strengthen content delivery. In a subsequent iteration, it would be useful to expose the learners directly to the writings of Ann Milne and others.

Feedback from colleagues suggests that Year 12/13 classes may be better suited for such a unit because of the dispositional maturity the topic requires. This is debatable, the project highlighted that many Pākehā Year 11 learners become cognizant of the topic’s relevance by the end of the unit. Furthermore, junior English has recently developed a unit on inclusivity that could scaffold learners toward the themes of the senior school unit. The unit content was stripped back significantly due to the unexpectedly limited knowledge of the learners about the New Zealand Wars and even the Treaty. A greater understanding of these issues in junior school would allow for more nuanced content exposure.

The safety of Māori learners within the classroom requires more focus. Comments made by some Pākehā learners could be quite offensive and greater safeguards are needed. It was also notable that Māori learners were also less likely to speak up in mixed-ethnicity audiences. Some Pākehā whānau had questions about the project, and in the future, I would begin with direct correspondence to whānau to explain the relevance of the unit to their child and their place in 21st-century New Zealand. This communication would highlight that learners are not taught ideological or political positions but rather supported in their own inquiries into the subject. Learners remain free to opt-out and begin ILPs at any time if disengagement and or extended discomfort are experienced.

Lastly, an authentic critical pedagogy of place necessitates experiences outside of the classroom walls. In a COVID-free world, a field trip to Kororāreka, Ōhaeawai, Ruapekapeka and/or Rangihoua would be a necessary experience, as would visits to local marae. The project would benefit from including direct discussions with Māori such as representatives from Ngati-Hine and experts rather than mediated experiences through texts. It would be interesting to trial the experience with a different assessment outcome other than formal writing. Both Māori and Pākehā learners reacted best to skits, satire and humour rather than to didactic historical documentaries. Indeed, while the subject matter is serious and significant, greater uptake and engagement would be achieved through more diverse content and assessment options.

Conclusion

This project explored the academic and dispositional effects on non-Māori learners of an English curriculum unit modelled on a critical pedagogy of place in a bicultural school in Northland. The unit encouraged learners from a dominant culture to research, reflect and consider solutions to evidenced inequalities for Māori. The motivation for this project was the increasing popularity of critically conscious and responsive pedagogy in New Zealand which is proving highly effective for Māori and Pasifika learners in ethnically homogenous schools. In schools of mixed ethnicities of Pākehā and Māori learners, the effects of such a programme are likely to be more complicated, as there are aspects of Pākehā learners’ culture that are being exposed to criticism.

The project’s primary objective was to track the assessment results and dispositional change in Pākehā learners’ understanding of Māori grievances and the socio-economic situation in contemporary New Zealand society. However, the project also highlighted that both Māori and Pākehā young learners had limited knowledge of their country and region’s history and the sociocultural context that has shaped it. The analysis of various written, visual and spoken texts on the issues exposed learners to perspectives and research they may not encounter in their everyday lives and communities. This resulted in a small but significant change in the perspectives of a target group of Pākehā learners. Some of them displayed quite considerable awareness by the end of the course, even though they were initially apathetic. Furthermore, with various degrees of success, the unit encouraged all learners to go beyond the surface of ethnic issues in their communities and address reasons and solutions for these. The results support the theoretical perspectives of Bowers (2008), and especially Penitito (2008), that a critical pedagogy of place can be meaningful to learners from the dominant culture provided that they explore the critical topic in a non-confrontational manner.

The methodological backbone of the project was a critical pedagogy of place, combined with the interactive approach of action research, which resulted in research and teaching occurring concurrently and the implementation of changes, some crucial, as the project developed. By locating myself in the research, I presented my own confusion and anxiety to my learners as normal and evidence of a shared learning experience.

The project has highlighted the potential for a critical pedagogy of place within the English curriculum to explore themes and topics at the heart of real-world concerns in Northland societies. The project depicted a way that schools can legitimise, support, provide the tools, and the safe space to analyse challenging aspects of New Zealand’s past and present. Having this analysis in school may depoliticise the discussion. It is hoped that there is the potential for developing greater tolerance and respect between ethnic groups in Aotearoa by doing so.

References

Belich, J. (1986) The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict. Auckland. University Press.

Bowers, C.A. (2008) Why a Critical Pedagogy of Place is an Oxymoron. Environmental Education Research. 14(3), pp. 325-33.

Education Council New Zealand–Matatū Aotearoa (2011). Tātaiako: Cultural competencies for teachers of Māori learners. Ministry of Education.

Ferrance, E. (2000) Themes in Education: Action Research. Providence, RI Northeast and Islands Regional Educational Laboratory.

Geertz, C. (1973) The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books.

Giroux H. (2011) Education and the Crisis of Public Values: Challenging the Assault on Teachers, Students, & Public Education. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Gordon, J. (2018) Critical Pedagogy in a Māori-Medium Setting. Te Kaharoa, 11(1).

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Vol. 74, Issue 6, pp. 1464–1480). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464

Gruenewald, D. (2003) The Best of Both Worlds: A Critical Pedagogy of Place. Educational Researcher 32 (4) pp. 3-12.

hooks, b. (1994) Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge.

McLaren, P. (1995) Critical Pedagogy and Predatory Culture, Oppositional Politics in a Postmodern Era. London: Routledge.

Milne, B.A. (2013) Colouring in the White Spaces: Reclaiming Cultural Identity in Whitestream Schools (Thesis, Doctor of Philosophy (PhD)). The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/10289/7868

Milne, B.A. (2016) Where am I in my School’s White Spaces? Social Justice for the Learners We Marginalise. Middle Grades Review. Social Justice: For Whom? 1(3).

O’Malley, V. (2015) Historical Amnesia over New Zealand’s Own Wars, The Dominion Post, http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/comment/67944795/Historical-amnesia-over-New-Zealands-own-wars

O’Malley, V. (2019) The New Zealand Wars: Nga Pakanga o Aotearoa. Wellington, Bridget Williams Books.

Penetito, W. (2008) Place-based Education: Catering for Curriculum, Culture, and Community. New Zealand Annual Review of Education, 18 pp. 5-29.

Shor, I. (1992) Empowering Education: Critical Teaching for Social Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sobel, D. (2004) Place-Based Education: Connecting Classrooms and Communities. Great Barrington, Massachusetts: Orion Society.

The opinions expressed are those of the paper author(s) and not He Rourou or The Mind Lab.

He Rourou by The Mind Lab is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. [ISSN 2744-7421]