He Rourou, Volume 1, Issue 1, 67-88, 2021

Iulia Leilua

ABSTRACT

This research was conducted in Auckland, New Zealand between November 2019 and April 2021. It outlines how emerging disruptive technology might help subject matter experts or professionals increase their Māori and Pacific cultural intelligence and disrupt systemic racism.

Bridging Cultural Perspectives looks at how subject matter experts might embed this knowledge so interactions with their Māori and Pacific stakeholders are more empathetic and culturally competent. It also explores the attitudes and behaviours that subject matter experts (SMEs) have that prevent them from becoming culturally competent or empathetic.

Phase 1 of this research identified the cultural intelligence challenges faced by subject matter experts and the types of support they needed. The aim was not only to improve their cultural ways of working but to unpack what systemic racism and unconscious bias at work looked like and how they might address these issues. Phase 2’s focus was to understand the drivers of systemic racism and to plan, execute, complete and evaluate a digital prototype that would disrupt these drivers. The aim was to achieve mutually beneficial outcomes when working with and for Māori and Pacific peoples.

This has resulted in two prototypes – the first is a digital platform for workplaces that uses nudge learning to raise peoples’ cultural intelligence through an organisation’s digital channels and devices. The second is a cultural intelligence academy that uses blended learning to raise the cultural intelligence of subject matter experts. Using systems practice, I also created a cultural intelligence framework and two systems maps that chart the deep structures of systemic racism and the behaviours that underpin them.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic racism impacts many aspects of Māori and Pacific peoples’ lives from health, justice and socio-economic wellbeing to media, business and housing. When organisations engage with Māori and Pacific peoples, cultural intelligence can help to disrupt this systemic racism. Cultural intelligence is the ability to cross boundaries, operate and work effectively in culturally diverse situations (Soon Ang, Linn Van Dyne 2009). This can only happen when people are interested and self-motivated to build relationships and work inclusively with people from other cultures. Structural discrimination occurs when an entire network of rules and practices disadvantages less empowered groups while serving at the same time to advantage the dominant group. (New Zealand Human Rights Commission, 2012). Participation by minorities is “conditional on their subjugating their own values and systems to those of ‘the system’ of the power culture” (p.19).

This project has given me the opportunity to speak candidly about systemic racism, discrimination and their cause and effects. Initially, words such as ‘unconscious bias’ and ‘cognitive bias’ were used to cushion my conversations with subject matter experts so as not to cause offence. That changed after the murder of black Minneapolis man George Floyd by a white police officer in May 2020. The fierce global response to his death and ensuing Black Lives Matters protests meant different conversations about racism were expected. Several of the subject matter experts I interviewed reflected on the social license that the world had been given to talk about structural racism and white privilege. At the same time, in New Zealand there were several moves to address and acknowledge racism. Media outlet Stuff acknowledged it had inflamed race relations through historic bias in its reporting and failing to provide balance and fairness to Māori. It promised to ensure that editorial staff were armed with knowledge of Māori tikanga and language and were committed to genuine diversity. Then in January 2021, the Ministry of Education released a draft new Aotearoa history curriculum for public feedback, which includes a deeper look at Māori history and colonisation. The content will then be taught in schools and kura in 2022 from entry-level in year 1 to year 10. From year 11, when students elect their subjects, it will be optional. As ground-breaking as these initiatives are though, widespread discussion on racism can be forgotten or diluted (Smith et al., 2021). For these reasons, shining a light on continued racism and their impacts on Māori and Pacific peoples is needed. It also means that innovative solutions using emerging disruptive technology are not only timely but important to changing the narrative about Māori and Pacific peoples.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In Phase 1 of this research, I conducted a literature review that focussed on understanding cultural intelligence and theories of achieving this. Cultural Intelligence (CQ) is defined as the ability to cross boundaries and thrive in multiple cultures (Middleton, 2014). Middleton says business teams made up of people from different backgrounds will out-perform those from homogenous teams – but only if they’re led by someone with a high CQ.

Leaders who have CQ don’t just cross the divides, they also build bridges for others to use. That is how they counterbalance the herding instinct that drags everyone back towards homogeneity – the default human preference for talking and working and sticking with ‘people like me’.

Cultural intelligence is about more than bridging national borders and developing your capability to operate globally. It is about crossing all kinds of cultural borders, learning to operate effectively in unfamiliar surroundings and finding a way to break down barriers that may well not be geographical at all. (Middleton, 2014, p.11-13)

In a 2006 report for the Economist Intelligence Unit, 90% of leading executives from sixty-eight countries identified cross-cultural leadership as the top management challenge for the next century. The executives said cultural intelligence was needed for:

· diverse markets

· a multicultural workforce

· attracting and retaining top talent

· profitability and cost savings (Livermore, 2015, p.17).

While many studies show diverse teams lead to greater innovation, Livermore (2015) indicates the benefits of that diversity can be squandered if leaders don’t have the cultural intelligence to ensure that all voices are heard.

In New Zealand, cultural intelligence is described as a critical skill in surviving and thriving in today’s global environment. Thomas and Inkson (2017) write that CQ means being skilled and flexible about understanding a culture, interacting with it to learn more about it and reshaping your thinking when interacting with others. The co-authors assert that cultural intelligence is developed through repetitive experiences over time in which each repetition of the cycle builds on the previous one. It involves both acquiring knowledge and applying that knowledge. Ways of developing cultural intelligence can include formal education and training, experiential learning and immersive experiences such as living and working in a foreign country.

Phase 1 of my research cast a wide net in terms of the literature I reviewed and theories I considered for understanding cultural intelligence and indigenous thinking. Because of this I explored five themes:

1. Cultural intelligence – what is understood by the term “cultural intelligence” both nationally and internationally, why it’s considered an important capability and how this is acquired (Inkson & Thomas, 2017; Livermore, 2015; Middleton, 2014).

2. Indigenous thinking – what is understood by the term “indigenous thinking” both nationally and internationally, and how these can be applied by SMEs (Pihama & Penehira, 2005; Simpson, 2004; Tuhiwai Smith, 1999, 2012; Tuhiwai Smith and & Te Rito, 2006; Yunkaporta, 2020).

3. Barriers to cultural intelligence and indigenous thinking – the barriers to raising cultural intelligence and indigenous thinking and contrasting rational, linear thinking with indigenous circular thinking (Tolich, 2002; Williams, 2008).

4. Systemic racism and unconscious bias – exploring white fragility, implicit race bias and systemic racism and its impact on raising cultural intelligence and understanding of indigenous thinking (Banaji & Greenwald, 2016; Bergner, 2020; Blank et al., 2016; Diangelo, 2018; Kempf, 2020, Torrie et al., 2015).

5. Positive models of cultural intelligence and indigenous thinking – exploring positive models both nationally and internationally of how SMEs could raise their cultural intelligence and indigenous thinking (Arago-Kemp & Hong, 2018; Spiller et al., 2017).

Phase 2 of my Bridging Cultural Perspectives research brought more clarity around understanding institutional racism and the human behaviours that drive it. I looked at other literature to understand prior work done on disrupting systemic racism as well as raising cultural intelligence. Global literature from Saad (2020) explores the elements that make up white supremacy including white privilege, white fragility, tone policing, white silence, white superiority, white exceptionalism, anti-blackness, racial stereotypes, cultural appropriation, white apathy, tokenism, optical allyship and more. Diangelo (2018) discusses what white fragility is, how it’s developed and how it protects racial inequality. Both Saad and Diangelo have chapters in their books which offer practical teaching tools for anti-racism education.

In New Zealand however, I found useful information from a network of Pākehā allies whose anti-racism and pro-Treaty of Waitangi work for social justice I have drawn on in this research:

Kotare Research – a Pākehā NZ organisation dedicated to research and education for social change. Their structural analysis research helped me to understand the workings of powers that drive systemic racism.

The Treaty Resource Centre – a Pākehā NZ organisation that educates New Zealanders about the Treaty of Waitangi. Its examples of white privilege and list of anti-Māori themes informed my systems mapping work. The anti-Māori themes included Pākehā as the norm, ‘One People’, Māori privilege, good Māori/bad Māori, stirrers, Māori violence, ignorance and insensitivity, the Treaty of Waitangi etc.

Network Otautahi – another Pākehā NZ organisation that educates New Zealanders about the Treaty of Waitangi. Its decolonisation posters for tauiwi (non-Māori) led organisations and non-Māori Kiwis clarified the way Pākehā educators teach anti-racism to other Pākehā.

Awea – a Pākehā NZ organisation dedicated to education for social justice. Awea’s resources for working as allies helps Pākehā understand how to support indigenous struggles for equality and anti-racism work in a range of social justice contexts. This includes understanding the term ally, their role as an ally, the qualities for being an ally and challenges and responses.

Groundwork – a Pākehā NZ organisation invested in creating systemic change and addressing systemic injustice. Groundwork offers workshops on the Treaty of Waitangi and organisational change and is led by Jen Margaret whose work on allyship informed my systems mapping.

As well as helping me understand and validate the elements of systemic racism that I included in my systems map, these research sources all offered solutions for disrupting systemic racism – and answering my research questions. Analysing the work of these system disruptors has been valuable for understanding the barriers and cognitive biases that subject matter experts have when raising their Māori and Pacific cultural intelligence. It has also been valuable for understanding the messaging that Pākehā system disrupters use when educating their own about the Treaty of Waitangi and systemic racism.

RESEARCH QUESTIONs

In order to achieve the aims and objectives described above, this research seeks to answer the main question:

How might emerging disruptive technology raise subject matter experts’ (SMEs’) cultural intelligence to disrupt systemic racism in the development of policies, systems practices, cultural engagement and strategies that affect Māori and Pacific peoples?

It also aims to answer the sub-questions:

1. What are the key barriers to subject matter experts raising their cultural intelligence and applying this to disrupt systemic racism in their policies, systems practices, cultural engagement or strategic work with or for Māori and Pacific peoples?

2. How might my findings inform subject matter experts and enable them to incorporate cultural intelligence in a way that disrupts systemic racism into their practice?

METHODOLOGY

Implicit throughout my research was recognition of the values that underpin Māori and Pacific approaches to community, knowledge and learning and teaching. In the field of Māori and Pacific cultural research, this methodology is standard practice. However, when it comes to studying systemic racism, the focus tends to be more on indigenous experiences of racism and colonisation.

This research was conducted using both kaupapa Māori and Pacific frameworks incorporating eight key cultural values as guidance.

Whakapapa

Whakapapa means genealogy, but for me, it also means recognising the diverse ancestral connections of my key stakeholders. In practice it means connecting with subject matter experts in a human-centred way rather than having a one-dimensional view of them as leader or practitioner. This can be done through introductions and reflections.

Tika and Pono

Tika and pono mean having integrity and doing the right thing. In the context of my research, it means behaving ethically and ensuring that my work is peer reviewed and checked for accuracy and authenticity. In practice it means creating a safe space for people to talk to me without judgement. It also means respecting their confidentiality.

Mana Tangata

Mana tangata in my project means empowering people and not denigrating them if they have lack of cultural knowledge. It means creating best practices for them to achieve good outcomes in the future when they work with Māori and Pacific peoples. It also means building their cultural confidence and capacity from a strengths-based approach.

Tautua

Tautua is a Samoa term which talks about leadership through service and humility. In practice it means having respectful relationships and professional behaviours when engaging with key stakeholders. Humility does not mean putting myself down, instead it means putting the needs of my key stakeholders first without making assumptions or judgement.

Manaakitanga

Manaakitanga means caring for people, but it could also mean caring for the information that is shared with me and ensuring it is used respectfully. In practice it means trying to reciprocate where I can by sharing about myself and keeping people updated about my research, even after it is implemented.

Fa’aloalo

Fa’aloalo is another Samoan term which means respect for people. In the context of my research, it means allowing people to define their own space and meet on their terms. As the researcher I will need to be flexible and responsive. In practice it also means acknowledging that peoples’ worldviews and ways of thinking are underpinned by their identities, languages and culture.

Kaitiakitanga

Kaitiakitanga means guardianship and protection. In the context of my research, it means acknowledging the trust that is given to me when key stakeholders share their knowledge. It recognises that with their trust comes expectation that I will create something beneficial using what they’ve shared. Kaitiakitanga for me also means nurturing relationships even after the project has ended.

Wairuatanga

Wairuatanga means spirituality and for me that comes with a Christian lens. In practice it wraps around all the other values like a cloak and expresses aroha to people regardless of their race, religion, gender or political beliefs. It acknowledges that design thinking, communications and technology draw from creativity and talents we were blessed with.

My approach to answering the research question was to use in-depth, qualitative exploration rather than quantitative numerical measurements, although I did conduct a survey with 34 people. A qualitative approach was the most suitable to answering my research question because I needed to contextualise the problem and gather deeper insights behind the causes and effects of racist attitudes and cognitive biases.

In Phase 1, I sought to understand the kinds of barriers that subject matter experts have that stop them from gaining cultural intelligence. In Phase 2, I went deeper into this investigation by mapping behaviours that affect cultural intelligence. I also sought to contextualise the system of racism by mapping it to find leverage points for changing peoples’ racist attitudes and behaviours or cognitive biases. The methods I used included critical thinking, systems thinking, design thinking, agile and theory of change. My aim was to find ways to disrupt systemic racism by providing practical solutions through emerging disruptive technology. This extended to gaining a deep understanding of the needs of subject matter experts and the kinds of cultural content and curriculums that would nudge them towards change. Through this methodology I arrived at several unexpected ideas and the implementation phase required specialised know-how from a team who has technical capacity and a wide network of subject matter experts.

Ensuring Rigour and Reliability

As an indigenous researcher it is not common for someone like me to research white subject matter experts about their biases and how to change their thinking through the use of technology. Despite looking for indigenous research about this topic, most of what I found focused on indigenous experiences of racism and colonisation.

During Phase 2 of this research, I challenged myself to cultivate moral imagination when questioning or analysing Pākehā who hold power. Moral imagination, according to Jacqueline Novogratz, CEO of Acumen Academy, and author of Manifesto for a Moral Revolution, is to have the humility to see the world as it is, and the audacity to imagine what it could be.

It starts by putting yourself in another’s shoes and building solutions from their perspectives. Moral imagination starts with empathy. But it does not end with empathy. Empathy alone risks reinforcing the status quo. Rather, the moral imagination requires immersing, understanding another’s problems, the situation around them, analyzing the system that has implication for those problems and then, importantly, taking action. (Novogratz, 2020, p. 17)

Practicing moral imagination was important for me during this research because of the lived experiences my family and I have had as victims of systemic racism. It also helped me find common ground with subject matter experts and decision makers who knowingly or unknowingly perpetuate systemic racism.

Interviews

To gain insight into the problems and solutions from my research question from a subject matter expert’s perspective, I conducted a series of semi-structured interviews with 13 subject matter experts. They were chosen from private, public, social enterprise and NGO organisations in tier 1-3 management categories and are decision makers, experts and influencers in their fields. These fields included Fintech, Construction, Commercial Communications, Economic Development, Human Resources, Global Research and Co-Design, Business Management and Design Thinking, Website Design, Government Procurement, Government Policy, Digital Inclusion and Digital Strategy. Because of COVID-19 or peoples’ geographic locations, most of the interviews were conducted over Zoom with just two done in person. Interviews were recorded and transcribed with the participants’ permissions.

There were five key questions that interviewees were asked:

1. How they connect with Māori and Pacific stakeholders;

2. The challenges they face with that;

3. Where they go to for Māori or Pacific cultural advice and support;

4. The kind of support they think would be helpful, particularly through the use of emerging disruptive technology;

5. How they would measure the ROI of becoming more culturally competent.

The questions were designed to be empathetic to help interviewees feel safe with sharing their personal and professional perspectives of Māori and Pacific cultural competency. Once the interviews were completed and transcribed, they were analysed to compare the similarities and differences between different interviewees’ experiences. I also conducted desk research, attended relevant webinars and online courses and reviewed presentations from our Tech Futures Lab advisors and guest lecturers.

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

Cognitive Bias and Behavioural Change

Cognitive bias can be used to describe people’s systematic but purportedly flawed patterns of responses to judgment and decision problems (Wilke & Mata, 2012). Some of the common types of cognitive biases include confirmation bias, conjunction fallacy, fundamental attribution error and in-group bias. Understanding biases and the way they can distort thinking was important for Phase 1 of this research because of the causes and effects they have on systemic racism. Unconscious bias or implicit bias is the bias you don’t know you have. It’s about the way your decisions and assessments are shaped by your background, cultural environment and personal experiences. Research shows that people who have very strong negative implicit biases about ethnic minorities consciously consider themselves fair-minded (Banaji & Greenwald, 2013).

Implicit race bias (IRB) has become a popular cultural topic in mainstream media, a popular area of research and debate in social psychology, and the common foundation for diversity training in countless corporate contexts (Kempf, 2020). But while implicit race bias offers a “relatively simple explanation of a very complex thing. It does not call for decolonization, for justice, or for the end of white supremacy” (Kempf, 2020, p.14.)

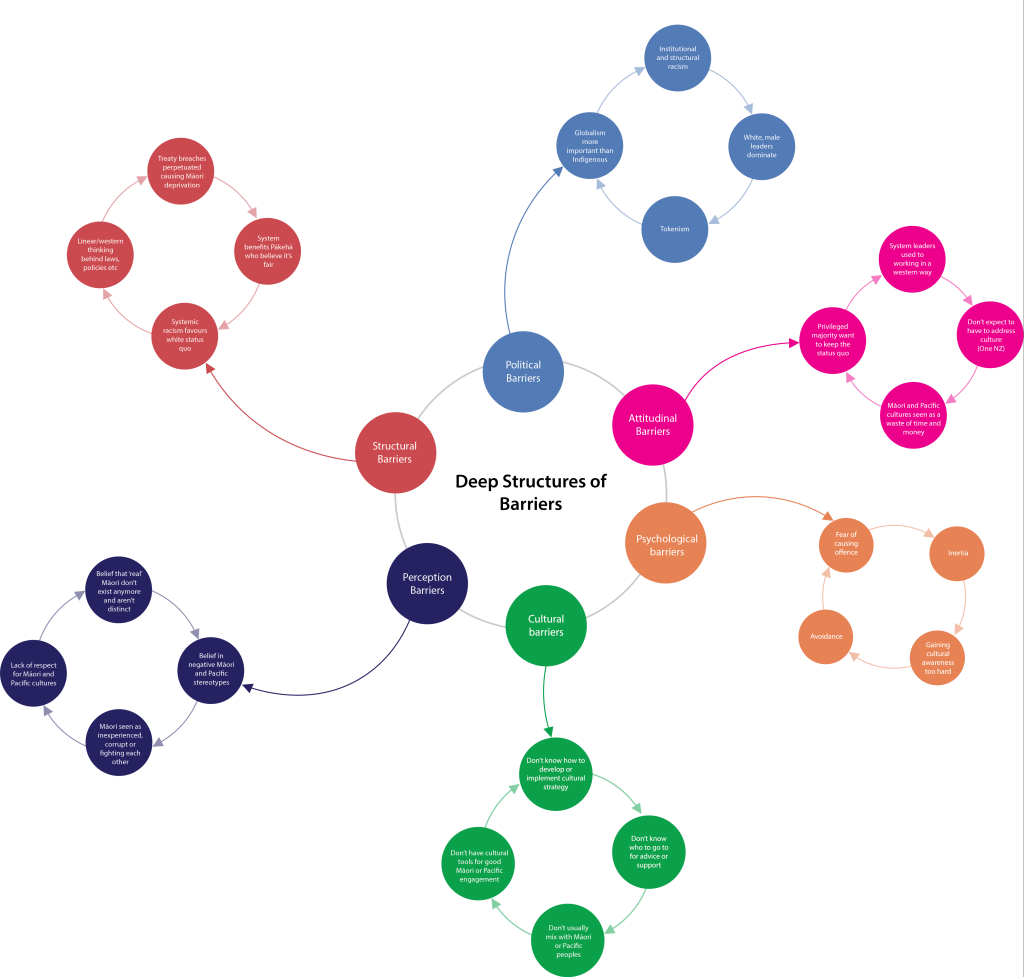

In Phase 2, I used systems mapping and the online software Kumu.io to map the deep structure of psychological, cultural, attitudinal, political, structural and perceptual barriers that subject matters face when it comes to raising their cultural intelligence. I was guided through this process by Acumen Academy’s 11-week Systems Practice programme from January to March 2021. It enabled me to:

· Map a complex system to gain clarity;

· Identify specific points in the system where a big impact can be made;

· Create leverage hypotheses to describe how systemic change might be created;

· Develop a framework for learning and adapting over time as the system changes.

This map is included in the key findings (Figure 1).

The data from the interviews was grouped into six categories of human behaviours: psychological, cultural, attitudinal, political, structural and perception barriers (Usha, 2016).

Disrupting Systemic Racism and Embedding Cultural Intelligence

Systems Practice and Mapping

Researching complex challenges such as how to disrupt systemic racism and raise the cultural intelligence of subject matter experts has required big picture thinking and systems practice in my work.

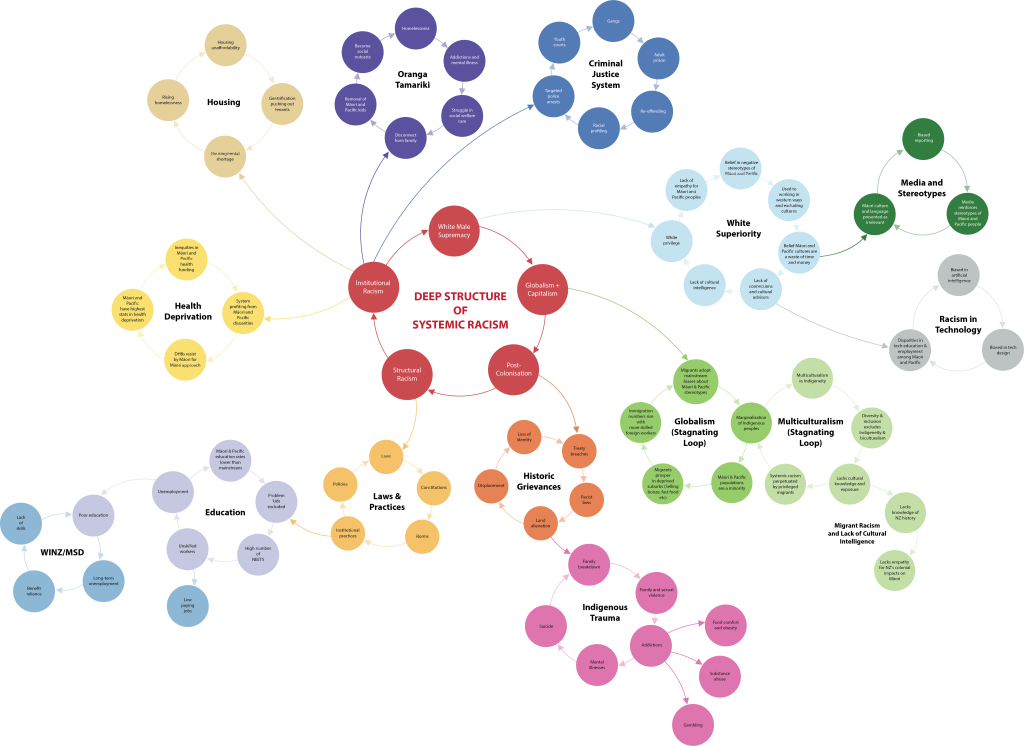

In Phase 2 it has required me to map out the web of interrelations that make up systemic racism and which perpetuate the downstream effects among Māori and Pacific peoples (Figure 2). I have also needed to map the psychological barriers that prevent or inhibit subject matter experts from raising their cultural intelligence. Systems practice helped me identify leverage points for amplifying cultural intelligence among subject matter experts and nudging the system to change itself. Systemic and structural racism in the development of policies, practices, cultural engagement and strategies is not well understood and there is diversity of opinion on how to solve this problem.

Quantitative Research

Although this research was predominantly qualitative, I also conducted a survey called the ‘Bridging Cultural Perspectives Survey’ using Survey Monkey. It was emailed to a range of Chief Executives, Senior Managers, HR Managers and Communications Managers in June 2020 and had 34 respondents. The survey was developed to answer my research questions and consisted of a range of multichoice questions. I decided to focus the questions on challenges engaging with Māori because there are subtle differences between Māori and Pacific cultures that would be hard to incorporate into just one survey. My intention was to run a separate survey related to Pacific peoples at the end of this project. Like the interviews, the survey work provided strategic opportunities to talk to subject matter experts, influencers and professionals that I wouldn’t normally connect with. My association as a Master of Technologies candidate with Tech Futures Lab gave credibility and weight to my work because of TFL’s reputation.

In Phase 1, 13 respondents had filled out my online survey and during Phase 2, another 21 people had answered my questions, bringing the total to 34. Twenty-four of the respondents opted in to receiving insights from my research. My insights report to them will summarise the findings from my research and be tailored around their comments and responses.

Analysis of Interviews

To understand the problems as subject matter experts perceived them, I interviewed 13 Pākehā subject matter experts from various industries including Business Management, Construction, Commercial Communications and Government Procurement. They represented a mix of private, public, social enterprise and NGO organisations from tier 1-3 management categories and brought a wealth of lived experiences to my research.

The research described in this report so far has looked at emerging and disruptive technology and systems practice. It has also focussed on attitudes to systemic racism, cognitive bias and barriers to improving cultural intelligence. But underpinning this was the all-important question: What do subject matter experts say are the cultural intelligence barriers they’re facing? An overview of these barriers can be seen in Figure 1 and described in more detail in the following section.

Psychological Barriers

In the 2015 research report Finding our way: Cultural competence and Pākehā evaluators, researchers assert that despite Pākehā dominance in New Zealand, many are not “fluent” in either the language or the culture of Māori or other ethnic groups. They say when such fluency is lacking, working in any cultural space other than their own is “to be ill-equipped to design and implement evaluations, or to analyse and interpret information that is gathered” (Torrie et al., 2015, p. 56).

Martin Tolich, coined the phrase “Pākehā Paralysis” to describe Pākehā nervousness and tentativeness about participating in research and evaluation with Māori. “Words such as confusing, complex, fraught, and fear of getting it wrong still inhabit conversations with some Pākehā colleagues about working cross-culturally” (Torrie et al., 2015, p. 54).

The common psychological barriers among some of the subject matter experts I interviewed were:

· fear of engaging causing confusion, inaction or inertia.

· not understanding the complexities of Māori social structures.

· not having cultural safety (Williams, 2008) processes in place.

Professor Tolich says one solution for a lack of cultural competency is to acknowledge that this problem is not Māori-centred but a Pākehā problem. “It is Pākehā who are paralysed here: unwilling or unable to think through this political minefield. Cultural safety has the potential to recognise and dissolve the Pākehā paralysis” (Tolich, 2002, p. 168).

Structural Barriers

In 2010, NZ’s State Services Commission’s reported that the high proportion of young people within the Māori, Pacific and Asian populations could be one of the reasons for lack of ethnic diversity in senior management. It said while most public service headquarters were based in Wellington, the largest populations of Māori, Pacific and Asian people were in Auckland. However, these factors alone do not account for overall under-representation. The report says that “for Māori, Pacific and Asian peoples, cultural differences may also come into play, along with direct and indirect discrimination” (Human Rights Commission, 2010, p. 44).

Eleven years later, some of the subject matter experts I interviewed were still grappling with the lack of Māori and Pacific representation in some workplaces and how to address this issue. They said this is because they:

· don’t know how to address the lack of Māori and Pacific representation in the workplace.

· want to be more relevant, welcoming and supportive to recruit more Māori and Pacific peoples but don’t know how.

Attitudinal Barriers

This research report was not only written in the first year of COVID-19 in New Zealand but also the fierce global outrage at the murder of black Minneapolis man George Floyd at the hands of a white police officer. Several of the subject matter experts reflected on the impacts that has had on conversations about structural racism and white privilege in New Zealand.

Many said the dominance of older, Pākehā men across boards and leadership roles in New Zealand held the status quo conditions in place. They said:

· subject matter experts need to unlearn racist behaviours.

· subject matter experts need to call out racism and bias and not be bystanders.

· subject matter experts need to be responsive and keep up with global conversations on racism that others in their industries are having.

They also disagreed with the:

· insistence on Western ways of working and not considering Māori and Pacific wisdom as a benefit.

· lack of indigenous diversity and inclusion.

Perceptual Barriers

Christian feminist and anti-racism worker, Mitzi Nairn, says she’s a proud Pākehā New Zealander. For the past 45 years she has educated other Pākehā New Zealanders about the Treaty of Waitangi and says there is nothing to fear because, “as we are being reminded in this document, the spirit of Te Tiriti is one of wisdom and care for all people.”

For many of the people I interviewed, an important step to cultural understanding was recognising the need to think long term when it comes to engaging with Māori and Pacific stakeholders. Many believed there was a:

. false and distorted perception of the process of colonisation.

· false sense of entitlement.

· need to think long term and adopt patient capital thinking.

Patient capital is needed to create sustainable future solutions for complex problems such as systemic racism. It avoids quick fixes that sees problems being repeated, creating new problems or making things worse through well-intended actions.

Cultural Barriers

The subject matter experts in this research project say lack of Māori and Pacific cultural intelligence means that working in a Western way is seen as the norm. Many felt this needed to change because:

· there is a lack of indigenous diversity and inclusion in the workplace.

· many subject matter experts still work in a monocultural way

· they are unable to facilitate engagement with Māori unless they have a Māori adviser or specialist.

· some subject matter experts place Māori cultural competency responsibilities on ordinary Māori in the workplace

When asked about the type of support they needed to work in a more culturally intelligent way, subject matter experts spoke about training and building their networks.

Political Barriers

Cultural competency depends on good relationships between Pākehā and Māori, however there are dynamics that sit between those who hold power and those who don’t. According to the Human Rights Commission, negative politics can erode fragile relationships and the progress made in policies, partnerships, practices or processes.

The subject matter experts interviewed said that:

· the power dynamics between those who hold power and those who don’t can affect fragile relationships with Māori.

· complex relationships between whānau, hapū and iwi and each other makes it difficult to know how to engage with them.

· there are a myriad of opinions about how to be culturally responsive.

· they need to differentiate between consultation and participation.

· they want to know how to co-design.

It’s not just political barriers from within institutional structures that can affect relationships. Political conflict among whānau, hapū and iwi can also damage relationships if they are perceived as constantly in turmoil. These conditions may exist among Māori because of the downstream effects of systemic racism or the complicated Treaty settlement process.

From analysing the interview data and investigating the barriers, I then looked at the survey feedback for more insights from the subject matter experts.

Analysis of Survey

As well as the interviews, I also received feedback from 34 subject matter experts in my Bridging Cultural Perspectives survey. Thirty-three of the participants were Pākehā and one was Māori. They worked in a range of sectors, most notably in local government (other):

Like the subject matter interviewees, the people I surveyed had similar psychological, cultural, perceptual and structural barriers:

· Fear of causing offence and not having enough budget to engage properly;

· Not knowing how to start the engagement process with Māori;

· The different attitudes to time which meant deadlines weren’t met;

· Unrealistic expectations from Māori about outcomes;

· Unrealistic expectations from participants’ jobs about reaching outcomes.

One participant said that structural racism and conscious and unconscious bias were challenges as was the “colonised view held by some Māori of their own identity and practice.”

Nearly 42% of those surveyed said the challenges they faced when engaging with Māori were having a moderate effect on their productivity or ability to achieve outcomes. However, 23% said the effects were a lot or a great deal.

In many cases the people surveyed said they had internal cultural advisors they could turn to for cultural support. The majority though used personal contacts and reached out to iwi, kaumātua, kuia and whānau for help. One person did not know anyone.

Although nearly half of the survey participants worked for organisations that had internal cultural advisers, there was still an appetite for more cultural learning and resource tools. Many said an online directory of cultural experts and advisers would be useful to call for help.

Similarly, the subject matter experts I interviewed suggested a mix of tools to support their cultural competency needs:

· An online resource site – Māori dictionary links, tips for engaging with manawhenua, high ranking on search engines;

· Virtual reality – learn from the past, create what the future might look like;

· Digital stories – bring Māori and Pacific stories to life that connect to language. Build out resources over time that capture colours and vibrancy;

· A language app – how to pronounce something;

· Podcasts and short videos – use for learning and understanding context of culture;

· Augmented reality on mobile phones – information, shopping, history; smart phones need internet, camera, GPS, software and compass;

· Online learning – cultural intelligence training online;

· An online directory of experts, guides and coaches – trusted advisors who can network and create authentic engagements.

Before COVID-19, people weren’t as willing to use online learning or communication tools, but a year after the pandemic hit, things have changed.

Interviewing and surveying these 46 Pākehā subject matter experts gave me deeper insight into the root causes that prevent them from raising their cultural intelligence. Fear or lack of knowledge about how to engage with Māori was common although many had internal cultural advisors they could refer to.

The inertia from predominantly older Pākehā male leaders who are used to Western ways of working keeps structural, psychological, attitudinal, cultural, perceptual and political barriers in place. The generations who came after them are more likely to have been exposed to Māori and Pacific cultures and are more likely to be receptive to change.

This is in line with important changes in the way that government, corporate and non-profit organisations seek to engage with Māori. The most significant change has been the recognition of the need to move away from one-off consultations to building meaningful and sustainable relationships (Bay of Plenty Regional Council Māori Policy Unit, 2011).

This survey suggests that subject matter experts want cultural intelligence to help them be more productive and successful in their work. The top topics that survey participants said they wanted to learn about were:

1. Building relationships with Māori;

2. Understanding and observing protocols;

3. Understanding Māori customer personas and Māori journey maps;

4. Understanding basic Māori language;

5. Understanding the Treaty of Waitangi.

I found the results overwhelmingly positive especially peoples’ candour. Using the technique of moral imagination also gave me the confidence to speak to them about sensitive issues and allowed them to feel safe and heard.

DISCUSSION AND CHALLENGES

Having looked at the cultural intelligence barriers that subject matter experts face, it was now time to uncover the story of systemic and structural racism and the forces that persist and drive these systems. I needed to look at the deep structures that underpin them.

Structural discrimination is described by New Zealand’s State Services Commission (1997) as occurring “when an entire network of rules and practices disadvantages less empowered groups while serving at the same time to advantage the dominant group” (p. 2).

My own views on the impacts of systemic racism on Māori formed part of a report on racism led by Māori research company Te Atawhai o te Ao. On Waitangi Day 2020, during a visit to Waitangi, I was invited to participate in their digital survey for a research report that was published in March 2021.

Called ‘Whakatika: A Survey of Māori Experiences of Racism’, it found the majority of Māori (93%) felt racism had a daily impact on them. Even more (96%) said that racism was a problem for their wider whānau.

The report defined four levels of racism as articulated in literature that they reviewed – internalised racism, interpersonal racism, institutional and/or systemic racism and societal racism. Systemic racism, as it pertains to my research question, is defined as:

Legislation, policies, practices, material conditions, processes or requirements that maintain and provide avoidable and unfair differences and access to power across ethnic/racial groups. This includes differential treatment and access to quality services in sectors such as education, health care, housing, employment and income as well as living in a clean environment (Smith et al., 2021, p. 16).

Figure 2 highlights the map of systemic racism which helped me to gain clarity on the entities that make up this system. I was also able to identify specific points in the system where big impacts could be made.

· Create leverage hypotheses to describe how systemic change might be created;

· Develop a framework for learning and adapting over time as the system changes.

As well as looking at the systems and the stubborn problems they create both upstream and downstream, I also had to understand the people who make up these systems.

Using insights from the subject matter experts I interviewed and surveyed, I mapped out the complex behavioural and structural elements that enable systemic racism to exist. I also added relevant insights from other publications and research.

As a form of peer review the deep structure of systemic racism map (Figure 2) was shared with three Māori women who work in the tech industry but are also Māori cultural advisors.

All three of the women were not surprised by the complexity of systemic racism. They resonated with the way the deep structure was laid out, and the connections between the loops that were put together. Also, they could see how their lives had been affected by the vicious loops that were plotted.

The question they asked is that, in every situation of systemic racism, where does the power sit and why is that? The participants talked about elements that were missing including digital racism, native language trauma, and white supremacy in the mental health and gender space.

There was concern about the future of work for Māori and Pacific peoples because of the inequitable access to internet connection, public services, public spaces, and job training in provincial and rural areas.

Although the system map was overwhelming for our participants to view (because of their own lived experiences), they appreciated the depth and clarity that the map gave. As a result, we will change our map to add some of their insights e.g. digital racism.

Conclusion and recommendations

Anti-Racism Education and Solutions

Māori have consistently protested about how the Treaty of Waitangi has been violated, but as well as that, from the 1980s, small numbers of Pākehā have always supported Māori.

The Pākehā Treaty workers’ movement emerged in the early 1980s in response to calls from Māori for Pākehā to learn about their responsibilities under the Treaty; Pākehā were challenged to educate their own people about it.

It was to these allies that I turned when considering solutions to systemic racism. Some, like Mitzi Nairn, are still involved 45 years on. It is my intention to build relationships with them after my deadline for this research, as fighting racism is an ongoing process that needs to be done with allies.

Disrupting Systemic Racism with Cultural Intelligence

Now that I had insights from subject matter experts about the barriers they face to increasing their cultural intelligence, and the insights into systemic racism, my attention turned to how we could disrupt system racism through cultural intelligence.

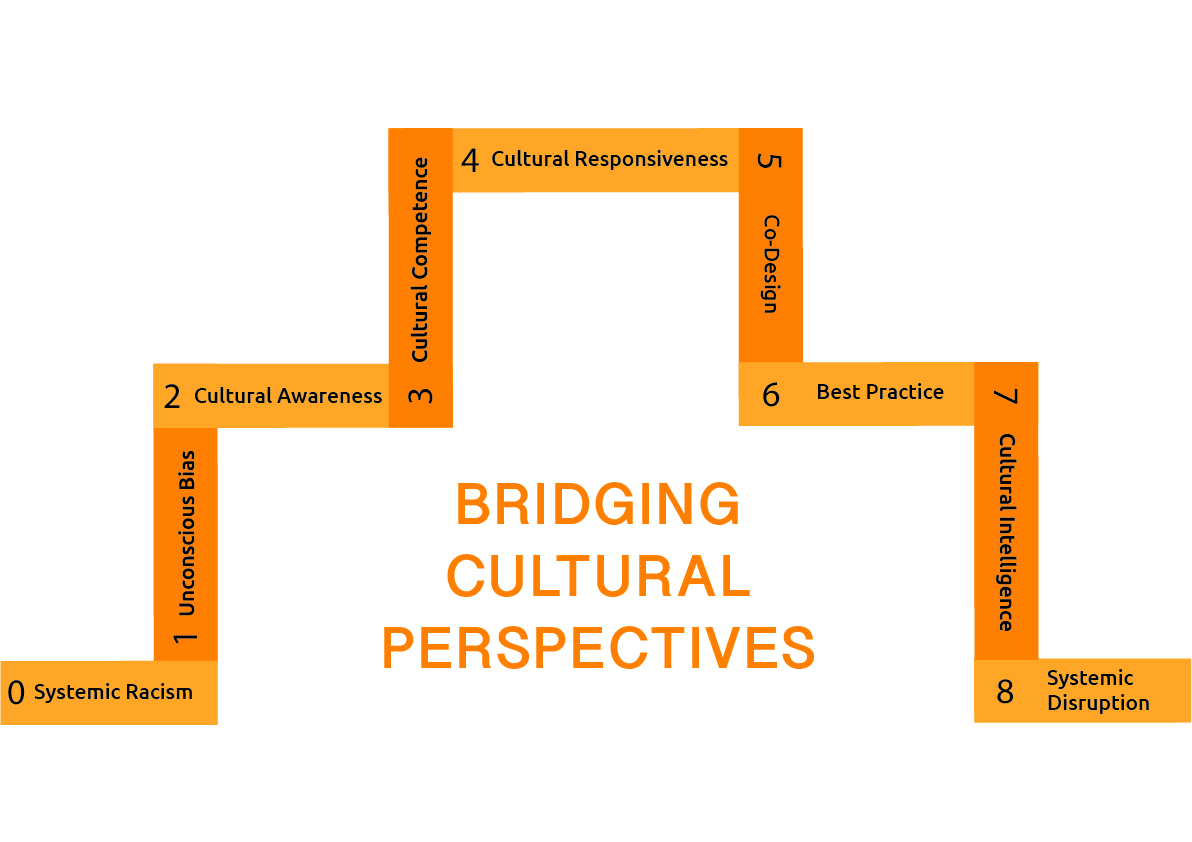

Subject matter experts are at different places on the continuum to becoming culturally intelligent and this can be a lifelong journey. Below is a journey map that I developed to chart the various stages along this CQ (also known in business as cultural quotient) continuum and where people might be at. The steps are built on the original ideas of Arago-Kemp and Hong (2018) who suggest cultural awareness and cultural knowledge are essential in bridging cultural perspectives. Figure 3 outlines the different types of solutions that my subject matter expert interviewees suggested that could be tailored for each step of their journey. The steps are by no means static and elements can be interchangeable.

Step 0: Systemic racism – Anti-racism education.

Step 1: Unconscious bias – Anti-racism and unconscious bias training.

Step 2: Cultural awareness – Treaty training basics.

Step 3: Cultural competency – Treaty training advanced.

Step 4: Cultural responsiveness – Strategic communications and marketing plans.

Step 5: Cultural co-designing – Cultural expert directory.

Step 6: Best practice implementation – Guides for engaging with Māori and Pacific peoples.

Step 7: Cultural intelligence – Cultural intelligence training.

Step 8: Systemic disruption – share insights and strategies with others.

This research aims to create broad and sustained changes so that subject matter experts know how to incorporate cultural intelligence into their work, thereby disrupting systemic racism. One subject matter expert I interviewed said knowing cultural competency wasn’t enough.

Helping them to journey from one end of the continuum isn’t necessarily linear or a one-way journey, but it is a lifelong journey that everyone, not just them, needs to achieve cultural intelligence.

SUMMARY

The key findings outlined in this report provide an insight into the cultural intelligence barriers that subject matter experts face. It also adds insights into the complexities of the environments that they operate in, the vicious loops and areas of stagnation.

It has required the “loose” holding of ideas and the ability to pivot from one idea to another. It has required moral imagination to gain the trust of subject matter experts.

Rather than focusing on the downstream effects of systemic racism on Māori, we have traversed the upstream waters to understand those who hold power there.

The result is there are two prototypes now in the pipeline – both underpinned by systems thinking, critical thinking, design thinking, agile, theories of change, teaching pedagogy, stakeholder journey mapping and kaupapa Māori and Pacific.

REFERENCES

Ang, S., & Van Dyne, L. (2009, 6). Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measureament, and Applications (1st ed.). Routledge.

Arago-Kemp, V., & Hong, B. (2018, 2). Bridging Cultural Perspectives.

Banaji, M., & Greenwald, A. (2013, 8). Blindspot: The Hidden Biases of Good People. Random House USA Inc.

Bay of Plenty Regional Council Māori Policy Unit. (2011, 6). Māori Engagement Guide: Engaging with Māori. http://stats.org.uk/statistical-inference/TverskyKahneman1971.pdf

Blank, A., Houkamau, C., & Kingi, H. (2016, 7). Unconscious Bias and Education: A Comparative Study of Māori and African American Students.

Came, H. and Zander, A. (Eds). (2015). State of the Pākehā Nation: Collected Waitangi Day Speeches and Essays. Whangarei, New Zealand: Network Waitangi Whangarei.

Diangelo, R. (2018, 6). White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard For White People to Talk About Racism (First ed.). Beacon Press.

Inkson, K, & Thomas, D. (2017). Cultural Intelligence [electronic resource]: Surviving and Thriving in the Global Village (Third ed.). Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Kempf, A. (2020). If We Are Going to Talk About Implicit Race Bias, We Need to Talk About Structural Racism. Ontario.

Levac, L., Baikie, G., Hanson, C., Stienstra, D., & Mucina, D. (2018). Learning Across Indigenous and Western Knowledge Systems Intersectionality: Reconciling Social Science Research. Approaches. Ontario.

Livermore, D. (2015). Leading with Cultural Intelligence: The Real Secret to Success.

Margaret, J. (2010). Working as Allies – Challenges and Responses. Retrieved from www.groundwork.org.nz/resources/allies-discussion-starters

McIntosh, P. (1988). White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women’s Studies. MA. www.nationalseedproject.org

McIntosh, P. (1988). White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. https://psychology.umbc.edu/files/2016/10/White-Privilege_McIntosh-1989.pdf

Media and te Tiriti Project, & Te Rōpū Whāriki, M. (2014). Alternatives to Anti-Māori Themes in News Media. https://trc.org.nz/examples-p%C4%81keh%C4%81-privilege

Middleton, J. (2014). Cultural Intelligence: CQ: The Competitive Edge for Leaders Crossing Borders. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Modernising Child Youth and Family Expert Panel. (2016, 4). Expert Panel Final Report: Investing in New Zealand’s Children and their Families. Wellington: Ministry of Social Development.

Network Waitangi Otautahi. (2020, 2). NWO Annual Report 2020. https://nwo.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/NWO-ANNUAL-REPORT-2020-Final.pdf

Network Waitangi Whangarei. (2015). State of the Pākehā Nation. (H. Came, & A. Zander, Eds.) Network Waitangi Whangarei. https://nwwhangarei.wordpress.com

New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs. (2019, 3). The Digital Inclusion Blueprint.

New Zealand Human Rights Commission. (2012). A fair go for all? Addressing structural discrimination in public services. Human Rights Commission. https://www.hrc.co.nz/files/2914/2409/4608/HRC-Structural-Report_final_webV1.pdf

Novogratz, J. (2020, 5). Manifesto for a Moral Revolution. Henry Holt and Co.

Pihama, D., & Penehira, M. (2005, 8). Building Baseline Data on Māori, Whānau Development and Māori Realising Their Potential Literature Review: Facilitating Engagement Final Report.

Saad, L. (2020). Me and White Supremacy: How to Recognise Your Privilege, Combat Racism and Change the World. Quercus.

Safe and Effective Justice (Independent Movement). (2019). Ināia Tonu Nei: Te Pūrongo a te Hui Māori.

Smith, C.-i.-t.-R., Tinirau, D., Rattray-Te Mana, H., Tawaroa, S., Barnes, H., Cormack, D., Te Atawhai o te Ao (Organization). (2021). Whakatika : A Survey of Māori Experiences of Racism. Whanganui.

Smith, L., & Te Rito, J. (2006, 6). Mātauranga Taketake = Traditional Knowledge, Indigenous Indicators of Well-being Perspectives, Practices, Solutions. Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga.

Spiller, C., Craze, G., Dell, K., & Mudford, M. (2017). Kōkiri Whakamua: Māori Management Report. Auckland.

Tolich, M. (2002). Pākehā “paralysis”: Cultural safety for those researching the general population of Aotearoa. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 19, 164–178.

The Independent Working Group on Constitutional Transformation. (2016). The Report of Matike Mai o Aotearoa.

The Ministerial Advisory Committee, Rangihau, J., Manuel, E., Hall, D., Boag, P., Reedy, D., Grant, J. (1988, 9). Pūao te Ata Tū. Wellington. http://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/archive/1988-puaoteatatu.pdf

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (1999). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. University of Otago Press.

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (Second ed.). Distributed in the USA exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan.

Usha, K. (2016). Communication Barriers Journal of English Language and Literature. Journal of English Language and Literature, 3(2), 74–76.

Wilke, A. (2012). Encyclopedia of Human Behavior (Second ed., Vol. 3). (V. Ramachandran, Ed.) Academic Press.

Williams, R. (2008, 5). Cultural Safety – What Does It Mean For Our Work? https://www.utas.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/246943/RevisedCulturalSafetyPaper-pha.pdf

Yunkaporta, T. (2020, 5). Sand Talk – How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World (First ed.). Harper One.

The opinions expressed are those of the paper author(s) and not He Rourou or The Mind Lab.

He Rourou by The Mind Lab is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. [ISSN 2744-7421]