He Rourou, Volume 1, Issue 1, 17-31, 2021

Jeska Martin

Abstract

Students in 2020 experienced unprecedented levels of anxiety and stress as a result of the global COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic affected not only students’ experiences of academic achievement in their first year of NCEA assessments, but also their wellbeing. This action research project, which was conducted with 23 female Pasifika Year 11 students, looked at the drivers of stress and anxiety in students, and investigated methods of minimising and managing these stressors. Another focus was the impact confidence has on agency and expectations of achievement in Level 1 NCEA. Data was collected through student voice, using small-group talanoa, one-on-one conversations, surveys, and conversations with staff.

My research findings indicate that students are not aware of the prevalence, nor normalcy, of anxiety and stress experienced by people in daily life. Conversations are presented confirming that students struggle to know how to manage achievement-related anxiety or cope in a learning environment when it becomes overwhelming. This work finds that students would appreciate teachers and adults being more transparent and vulnerable about their own anxieties, and that teacher practice would improve in turn. It suggests that classrooms that serve as safe spaces for mutual sharing about anxiety allow for the sharing and construction of healthy methods for dealing with achievement-related anxiety.

Introduction

This research began as a personal journey to build the confidence of Level 1 NCEA (National Certificate of Educational Achievement) Science students by scaffolding the breakdown of NCEA-style questions. The aim was, through creative activities designed around the specific language of NCEA, to improve the confidence of students thus giving them a better chance of success in Year 11 Science and therefore a future in science, technology, engineering, and/or mathematics (STEM). A lack of confidence is one of the most significant contributing factors for failure in Science (Cheema & Skultety, 2017). My initial hope was that by building the confidence of my students through these activities, more Pasifika students would continue taking Science at years 12 and 13, and even choose a STEM pathway when they leave school. There is a discrepancy in the number of Māori and Pasifika women in science in Aotearoa (Karmoka & Whittington, 2017), and I hoped to explore whether a lack of confidence during secondary school is a motivator for this.

Due to the effects of COVID-19, my project evolved to suit the needs of my students. It became clear, after returning from the second lockdown in Auckland, that my students needed support in a different way. They were still equally (if not more so) worried about their end of year exams, but for different reasons. My students were still lacking confidence, but what I also learned from them was that their worries were the result of time management, standards being cut due to time and so achieving fewer credits, and an inability to work from home due to a lack of a working device or internet access. Many students had to prioritise looking after younger family members during their “remote learning” time, with an example of several students studying overnight when the house was quiet, the computer free, or the internet accessible.

As the focus of what my students wanted to discuss with each other and with me shifted, I had a choice – would I stay on track with my initial project design, or would I be true to action research, and follow student voice and the needs of my participants? I chose the latter. As a result of this, the reasoning behind my research evolved and the method of data collection was revised. The overall motivation remained the same, but the focus shifted to unpacking the stress and anxiety students were experiencing that was impacting their confidence, and finding ways to manage and overcome those feelings.

Literature Review

The Impact of NCEA Assessment

The type of assessment has an impact on the type and level of anxiety experienced by students (Hipkins et al., 2016). I have observed that students find preparing for assessments (tests, exams, written assignments) more stressful than completing the assessment itself. The move from School Certificate to the New Zealand Curriculum was made to allow for vocational subjects (such as music, drama, woodwork, etc.) to be assessed and qualifications obtained in these areas. The move to NCEA has increased the number of students leaving with qualifications, and has become a more flexible and inclusive model of assessment. Despite this, NCEA still receives a lot of criticism (Hipkins, 2005; Hipkins et al., 2016). While traditional forms of examination do still exist, NCEA has been at the forefront of new and improved forms of assessment by allowing multiple assessments throughout the school year, rather than leaving all examinations until November. However, prior and alternative forms of assessment often result in higher levels of anxiety and stress, and there is some critique that by spreading assessment throughout the year (Hipkins et al., 2016), it is possible that we are building student anxiety throughout every day of a student’s existence at school. The way in which NCEA assessments have been changed has been a positive move, but is far from perfect. While a critique on the NCEA curriculum deserves its own thesis, it is important to consider this impact on student stress and anxiety when attempting to lessen these experiences in students.

The Impact of COVID-19 on Confidence

Confidence and self-efficacy are two similar terms with slightly different meanings. Bandura (1997) states that confidence is a colloquial term that refers to how much someone believes in themself, while self-efficacy refers to the belief in how agentic one can be, and how successful one will be in their chosen endeavour. While confidence and self-efficacy cannot be used interchangeably, for the sake of this research, I decided to look at both. The primary reason for this is that, as this research was done with 15-16-year-olds, confidence is a term they are more familiar with and a term that is more relatable, and therefore the term that was used in discussions with students. However, in many aspects, self-efficacy was technically more appropriate.

I have seen firsthand students lose their confidence when they cannot answer or complete the work they are given, and it proves a massive barrier to their learning. I can recount hundreds of examples where students can perfectly explain answers to me in person, but when given the same question written down, they fumble and lose confidence. My personal experiences from 2019 were the initial influence for exploring confidence through research; however, it was the unprecedented 2020 global pandemic, and the student responses to this pandemic, that caused this research to flow and change in the way that it did. My conversations with students showed that they were less confident in upcoming assessments than in 2019 as a result of COVID-19 and its impact on in-classroom learning compared to remote learning.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused large amounts of stress for secondary school students. According to the Health Promotion Agency (HPA, 2020), the COVID-19 lockdown period showed that youth in Aotearoa were disproportionately impacted by distressing events such as this, the Christchurch mosque shooting in 2019, and the 2011 Christchurch earthquakes. Katherine Liberty, a retired associate professor in child health, stated that the number of traumatic events, alongside their severity and duration, is a strong predictor for onset of psychological issues in adults (Graham-McLay, 2020). She stated that those that grew up in Christchurch during the series of earthquakes in 2010/2011 were five times more likely to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, including those who were in utero during those events. Secondly, Connolly (2013) states that existing inequalities, both educational and systemic, were expanded during the 2010 Christchurch earthquake disaster. Following the Christchurch 2010/2011 earthquakes, gaps in learning in students were widened as a result. Furthermore, when analysing the results of students who did NCEA in 2011, Connolly identified that there were greater discrepancies in achievement in the students who attended a low decile school when compared to results from 2009 (prior to major earthquakes in Christchurch). Additionally, distressing events such as the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing stressors and inequities (HPA, 2020). Many youth were reported to be worried about living in unsafe homes, and research has consistently shown that young people are particularly vulnerable to mental illnesses, and experiencing a traumatic event, such as COVID-19, can trigger the onset of genetically predisposed mental illness (HPA, 2020).

Project Aim and Questions

My Project Question was: How does stress and anxiety towards achievement as a result of COVID-19 impact confidence and self-efficacy leading up to NCEA examinations?

The sub-questions were:

- What does confidence look like in secondary school students?

- How does confidence affect students entering external examinations?

- What does anxiety look like in secondary school students?

- How does anxiety affect students entering exams?

- What strategies can be implemented to alleviate and manage stress and anxiety in school?

Methodology

Action Research

Action research was chosen to utilise a collaborative and interactive research project that works closely with the students (participants). The research was highly collaborative, and action research recognises the position of the researcher as being an active participant rather than an at-the-front leader (Bishop, 1999; Walker et al., 2001). In this way, action research is closely aligned with the idea of ako (reciprocal learning). Ozanne and Anderson (2010) comment that action research allows both researcher and participant to have a voice; a method widely encouraged in indigenous methodologies.

Project Design

This research was completed at an all-girls’ decile 3 secondary school in central Auckland, which has a predominantly Māori and Pasifika community, and this project took place exclusively with Pasifika students. Ethnic communities in New Zealand, including Māori and Pasifika students, regularly suffer great inequity and marginalisation due to Euro-colonially traditional learning in Aotearoa (Milne, 2016). Tomlins-Jahnke (2007) describes a mainstream school as one which privileges Western/Euro-centric education and traditions; similarly, Anne Milne (2016), finds the term mainstream to be an offensive term, and one which is judgemental and detrimental to Māori and Pasifika learners that do not excel in these environments. From my experience, most secondary schools (Kura Kaupapa Māori and designated character schools excluded) are structured around a Euro-colonially traditional learning curriculum, particularly designed in the early 2000s, but based on a structure from much earlier. Maurie Abraham, Principal of Hobsonville Point Secondary School, said that “secondary school students today are the first time travellers – they leave their house in 2020, arrive at school in the 80s, and when they leave they return to 2020” (personal communication, September 25, 2020).

The main form of data collection was through talanoa. Talanoa loosely translates to “talk” or “speak”, and refers to a Pacific method of sharing ideas in a relaxed environment (Lemanu, 2014). Most data was collected through small-group talanoa (rather than whole class), one-on-one conversations, and anonymous Google forms.

As a result of COVID-19, the data collection and therefore phases of action research were altered. Originally starting as large iterations taking several weeks, each phase evolved into smaller iterations and shorter time frames. Table 1 outlines the updated methodology and phases that occurred. Due to the lack of research time, phases two and three no longer occurred repeatedly and concurrently.

| Who does it involve? | What does it involve? | How will data be collected? | Research Question | |

| Phase One

(1 week) |

The participants and researcher | Establish the needs of the participants due to the impact of the pandemic | Classroom activities designed by researcher/small group discussions | Sub-Qs 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Phase Two

(2-3 weeks) |

The researcher and class volunteers | Collection baseline data, develop tutor time “activities” | Observations of participants, small group discussions, one-on-one discussions | Sub-Qs 2, 4, 5 |

| Phase Three

(2-3 weeks) |

Small selection of participants

School counsellor and Year 11 Dean |

Implement use of diary

Interviews |

Small group discussions, one-on-one discussions, anonymous survey

Voice recording/written transcription/email |

Sub-Q 5

Sub-Qs 1, 2, 3, 4 |

Summary of Action

Phase One – Establishing the Needs

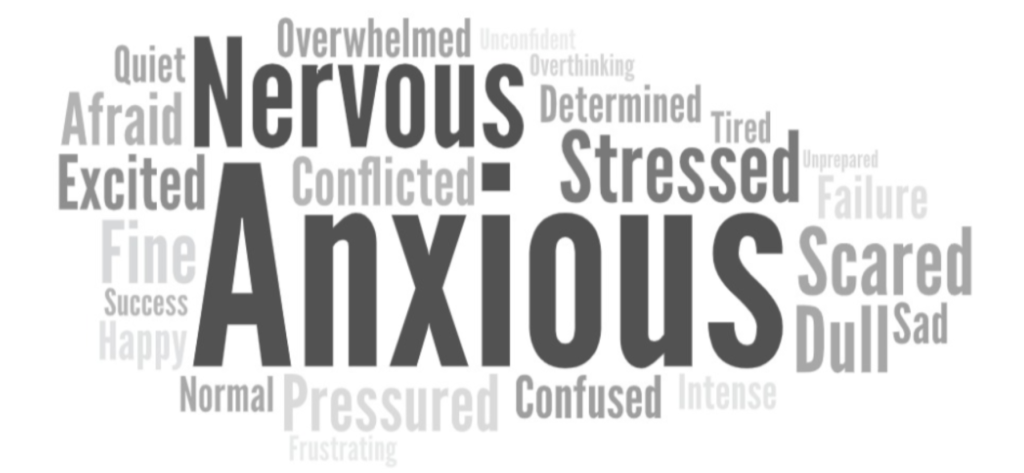

When we first returned to school post-lockdown, I asked my students “How do the upcoming NCEA exams make you feel?”, and students wrote down the key words that came to mind on a piece of paper (Figure 1). The students were not given a list to work from, although I gave examples to clarify the activity (“For example, you might write down worried because you are worried about your exams, or you might write down prepared because that’s how you feel.”).

The second and final class activity in this phase involved using the Blob Tree. The Blob Tree, designed by Pip Wilson and Ian Long (1980) shows images of “Blobs” that are neither male nor female, human nor non-human, and can be used to pinpoint feelings in a certain moment in time. In the image, the Blobs are standing, sitting, and falling off a tree. The Blob Tree can be used with young children or elderly and is a way for people to open up about their feelings without having to use words. I first asked the students to look at each of the Blobs and identify one or a couple of Blobs that they related to when thinking about their exam preparation and write that number down. I then asked them to write one sentence trying to explain why they felt they related to that particular Blob.

The below are comments from students about where they would place themselves on the Blob Tree, and why:

“Number 1 – I feel like I’m behind trying to catch up and everything is going fast.”

“Number 5 – I have no motivation to do anything. I can’t wait for this year to end.”

“Number 14 – I used to feel on track for everything but now everything is overwhelming and I’m behind.”

“Number 19 – I study but I fall asleep and I know I have to wake up and study again.”

“Number 21 – I feel like I’m watching everyone pass while I struggle.”

The Blob Tree website states “Without words, the Blobs can be interpreted in a hundred different ways. There is no right and wrong about the Blobs. […] The selection of a Blob is a snap-shot of how that person is feeling at that very moment” (Wilson & Long, 1980). I had used the Blob Tree previously with adults and had found the outcomes to be both thought-provoking and amusing. However, I did not expect such honest and open responses from my students about their feelings. While I am not trying to give any meaning to these comments made by students, it was these responses to the Blob Tree that made me pause; I did not expect so many of my students to feel worried, stressed, and overwhelmed about their end of year exams.

Both the word cloud and Blob Tree activities were implemented in July, after the first lockdown in Auckland. These responses were the data that impacted me and made me think; the data that caused me to change the direction of my project. Having learned that students were caught up in their own stress and anxiety, my research changed from helping my students gain confidence through creative literacy activities, to helping my students with their feelings about themselves and their upcoming exams. I knew that if I wanted my students to feel more confident in their abilities, I needed to first help them identify their stressors and what was causing them to feel anxious and nervous and follow the direction that my students (my participants and collaborators) needed the most. The next time I saw my students, I asked them what they thought, and what they wanted to do; I reiterated my original plan to break down NCEA questions and make them more manageable, and mentioned that I had been thinking about looking at the worries they were feeling about their external examinations. I was met with excitement, enthusiasm, but most importantly, relief; I could see in my students’ faces a slight weight lift from their shoulders.

Unfortunately, shortly after the first phase of my research, Auckland went into a second lockdown in August 2020, and we returned to learning remotely. This shook a lot of the students, especially the immediacy of the second lockdown. Despite this, students seemed to cope better than I had anticipated, and I learned that it was because we had done it before and came through the other side. When we returned to school, we discussed their (now even greater) worries about exams; however, their concerns were now not just about exams, but about their achievement in general. To achieve Level 1 NCEA, students must attain a certain number of credits, and many students aim to be endorsed with Merit or Excellence. Most teachers decided to cut down on the number of standards they were to cover in class, so that they could focus on getting the remaining standards achieved well, rather than attempt to rush through the original number of standards and have poor results. This caused many students stress because now they had fewer “chances” to achieve (there were fewer credits they could achieve in total, so it was more important that they achieve all of the remaining standards). This was reflected through a conversation I had with the school counsellor, who said:

There has been a significant increase in the number of students who are feeling overwhelmed, doubting their ability to achieve, and are concerned about their future. For many of the students I have worked with, the cloud of worry has affected their ability or confidence to stay engaged in their learning, to actually return to school, or to complete assessments to their usual standard.

Seeing the stress that my students were feeling, and hearing the school counsellor confirm their worries, I knew that I wanted to try and minimise the stress that my students were experiencing after hearing every teacher, every day, talk about how important it is to stay focused and study hard.

Phase Two – “You Time”

One thing I implemented to try and reduce my students’ stress while at school was to adapt tutor time, which is usually used for relaying notices, catching up on schoolwork, or studying, into “You Time” – free time that students could use in whichever way was most beneficial to them. I tried a couple of small iterations of this early on, so that I could use student responses to guide my next steps. By changing tutor time to become “You Time”, I hoped students could do whatever they needed at that time, on that day. Previously (between lockdowns), when I tried to engage students during tutor time with activities such as quizzes, making flash cards, or re-teaching challenging concepts, it was rare to get more than 50% involvement; by allowing students to choose their activity, the students were more engaged in the activity of their choosing. This changed daily depending on each student’s needs, but included activities such as relaxing on their devices, chatting with their peers, catching up on assignments, preparing for tests, researching future career choices and requirements, and sometimes taking a nap. This time was often quiet with students working individually or in small groups. I found that the students who needed to be catching up on work were doing this – there were students doing Mathematics practice, working on an English assignment, or making flash cards. The following are excerpts from conversations with students, and responses from an anonymous survey.

“I like [You Time] because I just get to ‘chill’ with my friends, & it gives us a break from all the work we did in the previous periods.”

“Tutor time is the only time where I can relax. I usually use our breaks to revise and maybe finish homework for other classes.”

“It is nice to have a break from having continually done work the whole day.”

“I think having free time is good for us to just catch up on other work. Especially next term with exams coming up, I think it would be really helpful if everyone could have that time.”

This began as a trial activity, to see if I could notice any changes in my students when they came to tutor time. Many students began to ask “Miss, are we doing anything in tutor time?”, and were always happy to hear it was “You Time”. During the second week, I noticed that opening up tutor time was having a positive impact on student wellbeing; my students were coming to tutor time happier, and many were choosing to stay in the same space during lunch time as well. To me, this meant that tutor time had become a safe space, which I hoped meant that they could relax here, but continue to turn up to their classes energised and ready to learn.

Phase Three – “Diary Day”

Another change I implemented to reduce the stress and anxiety identified by the students was to introduce “Diary Day” during tutor time on a Monday. Students were each given a small notebook which they could use however they wanted, though guidance was provided. The students were ensured these diaries were completely private. I often suggested that students use one page to write down anything that was making them stressed or worried, and on the next page write down all the little things they can do to overcome some of those tasks. The following are excerpts from conversations with students, and responses from an anonymous survey.

“Using the diary helps me to keep track of my learning.”

“I like having a dedicated space to write all my worries down.”

“Knowing that no one else would read what I was writing or judge me for what I was worrying about was really nice.”

“I like that I am able to write all my stressful school assignments down and know that I can plan for them.”

“I like that I can express my feelings in this little notebook. It’s refreshing and a stress relief writing about my to-do’s for the week & what’s stressing me out. I like seeing those things on paper and realising what I have to work on.”

“I like using my journal because sometimes the things I write down on paper help me identify what things I should stop worrying about or should focus on getting better at.”

All students who responded to the survey shared positive statements about their diary. When reflecting on these comments, I was pleased to see that they were getting something useful and positive out of the diaries – be it to organise and plan, or a way to express their feelings. I was glad that my students had a place to write their worries down and know they wouldn’t feel judged for what they were writing. A conversation with the school counsellor highlighted this as something many students are lacking. “Many of the students I have been supporting have kept their anxiety to themselves at home, as talking about their stress, showing vulnerability, or asking for help is not something that is encouraged or they feel comfortable doing.”

After about two weeks, it became normal that tutor time could be for whatever was needed. Students were happy entering the room, and the class was a lot less disruptive. It wasn’t until one day when a senior colleague walked through my classroom and acknowledged that students weren’t studying that I realised something: what was happening in my classroom was a break away from the norm. I was “taking a risk” by allowing my students “free time” instead of organising revision activities or ensuring every student was studying. Below is an excerpt from my own journal after this encounter.

Today a senior colleague walked through my class during tutor time, and said to my students, “Why aren’t you studying? Don’t you have exams in three weeks? You know you have a Science teacher here who will happily help you with your Science revision!” I could see that my students were taken aback, and felt guilty. One student even asked “Miss, why did she tell us off for not studying when you said it was okay?”

This event made me particularly uncomfortable, but it was not until a later reflection that I realised why this was. My students had finally become comfortable, after two major disruptions due to COVID-19, and it was important to me that my students kept that sense of comfort in my class during these unprecedented times. It is part of my duty as tutor teacher of the Pacific Health Science Academy to provide extra Science support during tutor time – this may come in the form of recapping content taught in class, giving tutorials, or providing resources to prepare for exams. At the time, my role as tutor teacher in the Pacific Health Science Academy made me feel guilty for not providing that Science support, but as I pondered over the coming days and weeks, I realised that I was still supporting my students; in fact, I was supporting them in the way they needed the most.

Perhaps most importantly, in terms of my change in thinking, was something a student said to me one day, after I was sharing how I was also stressed because of the circumstances; I had to plan lessons, complete marking, write assignments, and respond to emails, as well as everyday household chores. I was describing how everyone experiences stress, and how stress can be a good thing, until it becomes too much and impacts your daily life. The student said to me:

“Most adults or teachers don’t talk to us when they are feeling stressed, so I didn’t know that it’s normal.”

This was met with nods and noises of agreement from other students. To me, this is one of the most integral findings of my whole research; to learn that students and youth do not know how common it is to experience stress in daily life. While I will argue that experiencing major stressors every day is not normal, it is expected that in life every individual will experience some kind of regular stress as well as some major stressors.

Discussion of Findings

Anxiety and Stress

When considering stress and anxiety in students, we must also consider that both are expected and normal in students, and people in general. Lisa Damour (2019) claims that anxiety and stress are normal, and essential for human growth and development; however, there are both “healthy” and “unhealthy” states of stress and anxiety. She states that healthy forms of stress can occur when an individual takes on new challenges or does something that feels uncomfortable and threatening. By continually doing things that challenge us, we gradually build our capacity to tolerate stress. This explains why most adults are more adept at handling stressful situations compared to children and teenagers.

Damour (2019) also mentions that stress can be divided into three distinct categories: chronic stress, life events, and daily hassles. Students in 2020 are often experiencing all three kinds of stress, and often at the same time. Their daily hassles may include chores, and looking after younger family members; upcoming NCEA internal and external examinations come under life events; and the global pandemic COVID-19 can be suitably classified as a chronic stress. It is unsurprising that students and children are feeling more stress than usual in these unprecedented times. Furthermore, Damour indicates that the number of daily stressors an individual must overcome has a significant impact on how well a person can cope with a major stressor. Through conversations with Pasifika students, I am well aware of the wealth of responsibilities that they are expected to fulfil outside of their education. We can therefore infer that these extra responsibilities may have impacted their ability to cope with the immediacy of the pandemic.

Most of what children learn about stress and responses to stress comes from seeing how adults in their life manage stressors (Damour, 2019), and so I come back to this quote by a student:

“Most adults or teachers don’t talk to us when they are feeling stressed so we didn’t know that it’s normal.”

As an adult and teacher I try to protect my students from having to undergo unnecessary anxiety and stress. This may be by not fully sharing the worries I have when it comes to their achievement or number of credits attained, sheltering students from the words I have heard from other teachers, or by not (at least trying to not) displaying my own stress and anxiety when I am with them in the classroom. I make a particular effort not to bring my personal difficulties to my students and instead try to always bring my best self. As a result of this, this version of me is what they always see; an adult who is put together, organised, and confident – a person that I am not! I am riddled with anxieties and stress, often disorganised, and rarely confident in myself, especially when presenting “in front of a crowd”, but I put these aside when I walk in the door so that my students can see someone who they expect to see as a teacher. Reflecting on the statement by a student above on knowing that it is normal to experience anxiety and stress, I wonder; should adults and other role-models for children be more open about their lives when it comes to stress and other problems they are experiencing? Opening up about these struggles makes one more vulnerable, which is not always a position one wants to be in as a teacher; however, I argue that sharing these thoughts and feelings with our students, when appropriate, is a valuable life lesson. I wonder if, by sharing these experiences with students, we not only become more “human” but also more relatable, and if we are more relatable, we are able to have better relationships, and therefore be able to teach and help our students to learn and achieve more successfully. As a teacher I rely on using relational leadership, and by building those relationships with my students first, I become a better teacher and therefore my students are more successful learners.

Lastly, Damour (2019) states that barriers and hurdles only make us stronger if we can overcome them, and Morony et al. (2012) state that students regularly avoid stressors due to the negative experience. Thus, how are students able to grow and build their stress capacity? I have seen, at least within the context of my own school, that teachers often “coddle” students over the line of achievement so that they can achieve their credits. Whether this “coddling” is done for the benefit of the student, or benefit of the teacher and their end of year data, is sometimes questionable. Firstly, this is a strong disadvantage of using NCEA as a measure of achievement especially considering that missing one key word can be the difference between achieving and not achieving (Hipkins et al., 2016); however, this is a discussion too large in the context of this research. Secondly, this “coddling” of students does not help students in terms of overcoming a challenge. If we are constantly helping to ensure students achieve, we are actually disadvantaging our students by not allowing them the challenge to overcome this obstacle, this daily stressor, on their own, so that they can build up their “stress capacity” and continue to overcome more and more challenging stressors as they reach adulthood and are burdened with more responsibility. This is a point of contention in my school environment, and one that at this stage I do not know the answer to; however, I will now be thinking much more carefully when helping or advising my students. From now on, I will try to lead more often by providing help, but not by providing answers.

Student Wellbeing

It is concerning to me that students are experiencing stress and anxiety in several different areas of their life, exacerbated by COVID-19 – there is stress at home, at school due to assessment, in friendships, at work, and in extracurricular activities. In many young people, quality of life is greatly influenced by happiness, enjoyment, and a sense of wellbeing at school (De Róiste et al., 2012), and when this is missing, students are likely to feel sad and depressed. I believe this is what is happening with my students, and most students, this year, which was confirmed in a conversation with the school counsellor:

There has been a significant increase in the number of students who are feeling overwhelmed, doubting their ability to achieve, and are concerned about their future. For many of the students I have worked with, the cloud of worry has affected their ability or confidence to stay engaged in their learning, to actually return to school, or to complete assessments to their usual standard.

I posit that if a student is experiencing this amount of stress, which is affecting their happiness and enjoyment not only at school but of life in general, that the wellbeing and quality of life of students must also be on the decline. Both Oakley-Browne et al. (2006) and Gibson et al. (2017) claim that Pasifika youth are twice as likely to suffer from serious mental health diagnoses (including anxiety and depression) than the rest of the population. It should also be considered that Pasifika youth are less likely to be diagnosed with any mental health conditions (HPA, 2020). The Year 11 Dean noted a change in student wellbeing this year, as quoted below.

In students (and staff) the little moments that trigger big explosions are on the rise. We are trying to “keep the small things small” [and] I think that is becoming more difficult, both in terms of relationships between students, between staff and students and also in terms of how students talk to themselves. I see this as a sign of stress… It is almost as though once we have addressed the low level of credits and put plans into place to catch them up, they then break down in tears and tell me other stuff about how they are feeling.

The Dean also noted a change in the behaviour of staff as a result of added stress from COVID-19, and that it was affecting relationships between staff and students which, according to relational leadership, is the key to being a good leader and therefore a successful teacher. The school counsellor also noted the effect of staff stress on students’ wellbeing.

Some students were really affected by their teacher’s response. Particularly after the first lockdown, many students said they felt so overwhelmed by the emails teachers bombarded them with that they didn’t know where to start or how they could possibly meet the teachers’ perceived endless demands.

To me, this all comes back to finding the fine line between modelling life stress as an adult and teacher by being vulnerable and sharing successful and beneficial coping mechanisms, whilst also remaining professional and demonstrating positive leadership.

Confidence

The students/participants who were involved in this research are primarily a very agentic group; these students voluntarily complete work during tutor time, and are rarely (if ever) in “trouble” with other teachers. They had to apply to be part of the Pacific Health Science Academy, producing an essay and handing in an application form before the due date. These things, as well as knowing the students personally, leads me to believe they have average if not high levels of agency. The question I now ask is, do the students know this, and does their agency (or self-efficacy) affect their confidence in themselves? When I asked the Year 11 Dean about confidence in students this year, she said:

“[There are] more students who feel that they will not be able to achieve [this year].”

This could indicate that students are more anxious this year as a result of COVID-19, the decreased in-school learning time, and the reduction in assessment opportunities. Furthermore, when talking about the implications of COVID-19 and its effect on confidence in Year 11 students, the Year 11 Dean said:

My concern is that some [poor] habits may have formed. In many ways, NCEA Level 1 is where we set the patterns and habits for Level 2 and 3 which are far more important. That is why it is important that students learn about planning their time, keeping to deadlines, and going to the externals even if they have already passed the course.

Reinforcing some of these effective study skills during tutor time by providing diaries where students wrote their stressors and plans to overcome or reduce these, and hearing about the importance of developing study skills from the Year 11 Dean, gave me hope that I was providing my students with some lifelong strengths. This comment also reinforces that, as teachers and educators, while we know Year 11 is useful, (particularly at this secondary school where it is the students’ first experience of exams), in the scheme of things, the following two years are of a greater importance, both in terms of the number of credits and achieving NCEA, but also in terms of further education. Despite this, it is also important for educators to recognise that the stress and anxiety experienced by students at Level 1 is just as real and formidable as those experiencing the same feelings at Level 2 and 3.

I do, however, wonder about the students who did not have regular access to devices and the internet and therefore struggled with an online learning environment. According to the school counsellor:

[Students are] absolutely less confident because this experience has been so foreign to them, and had such an impact on their usual routine and way of learning that they’ve found it hard to be hopeful or feel that they have it together. […] In addition to the usual stressor of having to adjust to remote learning, many of our students had to juggle huge family responsibilities and try and muddle their way through their learning with massively limited resources e.g. no laptop or wifi or sharing a device. The inequity that I saw as a result of COVID, experienced by many [of our] students, only served to heighten their stress and distress.

This comment confirms a link between a lack of confidence in students and the stress experienced by students, which was further exacerbated by remote learning and the challenges this presented.

There have not been many large-scale studies looking at confidence in education (Morony et al., 2012). I theorise that this is in part due to the difficult nature of measuring confidence, particularly as it cannot be universally defined or put upon a scale. When I considered confidence in terms of my participants, I looked at the language they were using with their peers when discussing upcoming assessments. I did not hear any students openly admitting they “felt confident”; however, students were not shy to say that they had studied the best they could and “hoped” they would do well, which I inferred to mean they felt partially or fully confident. Other students often said they were “scared” or “worried” about an assessment, which I inferred to mean they were feeling unconfident. Interestingly, Morony et al. (2012) found that, despite boys and girls achieving similarly, girls rated their confidence (in achieving in mathematics) and self-efficacy much lower, and anxiety much higher, than their male counterparts.

Conclusion

It is too early at this point to conclude from this research that a causal relationship exists between helping students recognise their anxieties and seeing positive outcomes for their wellbeing (and therefore achievement); however, comments from students have suggested that using a diary or journal to plan, prepare, and identify potential stressors has helped them feel more in control. Further conversations with students have prompted the idea that adults need to be more open in terms of when they are experiencing stress, and what methods and strategies they use to manage and overcome these stressors, so that students can learn and continue to grow as people.

Action research and inquiry-based research were key methodologies to this project’s success, as it not only allowed for quick changes to be made in implementation, but meant that student voice was the predominant leader with respect to the direction of this project. I learned that, by taking a risk in shifting away from “the norm”, I provided students with a dedicated time to relax, destress, and then show up to their next class with a positive attitude towards learning.

As a teacher, I have learned that there is a need for me to exhibit vulnerability in order to be a more effective educator, particularly when modelling positive wellbeing practices for my young female Pasifika students. Moreover, this project has shown me that participating in being vulnerable as a practitioner allowed me to discover unexpected learnings about the enormous stress that students experience in order to achieve – even (and especially) when academic achievement is not a student’s top priority.

References

Anderson, D. L., & Graham, A. P. (2016). Improving student wellbeing: having a say at school. School Effectiveness and School Improvement 27(3), 348-336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2015.1084336

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W. H. Freeman.

Black, P. (2001). Report to the Qualifications Development Group, Ministry of Education, New Zealand, on the proposals for development of the National Certificate of Educational Achievement. London: School of Education, King’s College, London. Report commissioned by the Ministry of Education.

Bishop, R. (1999). Kaupapa Maori research: An indigenous approach to creating knowledge. Robertson, N. (Ed). Maori and psychology: Research and practice. Proceedings of a symposium sponsored by the Maori & Psychology Research Unit, Department of Psychology, University of Waikato, Hamilton, Thursday 26th August 1999 (pp.1-6).

Cheema, J. R., & Skultety, L. S. (2017). Self-efficacy and literacy: a paired difference approach to estimation of over-/under-confidence in mathematics and science-related tasks. An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology, 37, 652-665. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2015.1127329

Connolly, M. J. (2013). The impacts of the Canterbury earthquakes on educational inequalities and achievement in Christchurch secondary schools (Master’s Thesis). University of Canterbury, Canterbury, New Zealand.

Damour, L. (2019). Under Pressure: Confronting the Epidemic of Stress and Anxiety in Girls. New York: Ballantine Books.

De Róiste, A., Kelly, C., Molcho, M., Gavin, A., & Gabhainn, S. N. (2012). Is school participation good for children? Associations with health and wellbeing. Health Education, 112(2), 88-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09654281211203394

Freeman, C., Nairns, K., Gollop, M. (2015). Disaster impact and recovery: what children and young people can tell us. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 10(2), 103-115. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2015.1066400

Gibson, K., Abraham, Q., Asher, I., Black, R., Turner, N., Wait-oki, W., and McMillan, N. (2017). Child poverty and mental health: A literature re-view (Commissioned for New Zealand Psychological Society and Child Poverty Action Group).

Graham-McLay, C. (2020, May 30). “’There’s a huge amount of anxiety’: New Zealand wrestles with back-to-school virus blues; Researchers are urging mental health strategies for students after Covid-19, devastating earthquakes and a deadly terrorist attack. How will the Covid-19 generation cope with the fallout?” The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/global/2020/may/30/theres-a-huge-amount-of-anxiety-new-zealand-wrestles-with-back-to-school-virus-blues

Griggs, M. S., Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Merritt, E. G., & Patton, C. L., (2013). The responsive classroom approach and fifth-grade students’ math and science anxiety and self-efficacy. School Psychology Quarterly, 28(4), 360-373

Health Promotion Agency. (2020). Mental Distress and Discrimination in Aotearoa New Zealand. https://www.hpa.org.nz/sites/default/files/Mental%20distress%20and%20discrimination%20in%20Aotearoa%20New%20Zealand%20-%20report.pdf

Health Promotion Agency. (2020). Post-lockdown survey – the impact on health risk behaviours. https://www.hpa.org.nz/research-library/research-publications/post-lockdown-survey-the-impact-on-health-risk-behaviours

Health Promotion Agency. (2020). Rapid Evidence and Policy Brief: COVID-19 Youth Recovery Plan 2020-2022. https://www.hpa.org.nz/research-library/research-publications/rapid-evidence-and-policy-brief-covid-19-youth-recovery-plan-2020-2022

Hipkins, R. (2005). The NCEA in the Context of the Knowledge Society and National Policy Expectations. New Zealand Annual Review of Education, 14, 27-38.

Hipkins, R., Johnston, M., & Sheehan, M. (2016). NCEA in Context. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 53, 143-145.

Lemanu, T. (2014). Creating the ‘talanoa’ conversation is all it takes. Pasifika Education. Obtained from: http://blog.core-ed.org/files/2014/12/talanoa-diag.png

Morony, S., Kleitman., S., Lee, Y. P., & Stankov, L. (2012). Predicting achievement: Confidence vs self-efficacy, anxiety, and self-concept in Confucian and European countries. International Journal of Educational Research, 58, 79-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2012.11.002

National Research Council. (1996). National science education standards. Washington, DC: National Academic Press

New Zealand Qualifications Authority. (n.d.) History of NCEA. Retrieved 6 October, 2020, from https://www.nzqa.govt.nz/ncea/understanding-ncea/history-of-ncea/

Oakley-Browne, M., Wells, J., & Scott, K. (2006). Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey. Ministry of Health: Wellington. Retrieved from https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/te-rau-hinengaro-new-zealand-mental-health-survey

Tomlins-Jahnke, H. (2007). The place of cultural standards in indigenous education. In American Education Research Association Annual Conference. Chicago, IL.

Wilson, P., & Long, I. (1980). What Are The Blobs? A Feelosophy. Retrieved 30 September, 2020, from https://www.blobtree.com

The opinions expressed are those of the paper author(s) and not He Rourou or The Mind Lab.

He Rourou by The Mind Lab is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. [ISSN 2744-7421]