8

Kendra Grant

Abstract

This chapter explores how rapidly changing and ubiquitous technologies, including mobile devices, free online tools, social networks and instant connectivity, have fundamentally changed the ways people interact, socialize and learn. However, new technology too often reinforces old methodologies. Rather than act as a tool for instruction or a vehicle for delivery, technology can serve as a catalyst for change. In this chapter, video, through both its familiarity and DIY potential, will act as this catalyst. Viewing and applying video in a very different way requires a series of lenses to examine practice, presence and production. The first lens frames technology’s use and encourages change. The RAT Model – replication, amplification and transformation (Hughes, Thomas, & Scarber, 2008) – guides the application and use of technology to help transform instructional practice. The second lens examines the Community of Inquiry model (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000) created by the intersection of cognitive, teaching and social presence. This chapter explores how video can help create collaborative environments for deep learning by supporting each presence. The third lens explores design presence: a combination of production, accessibility, and aesthetic principles that help ensure a quality product (video) that supports social, cognitive, and teaching presence. Together, the three lenses take video, an often transmissionist tool, and examine it to help change pedagogical practices to support a positive learner experience (LX).

Keywords: video, community of inquiry, online learning, social presence, teaching presence, cognitive presence, design presence, connectivism, replication, amplification, transformation, accessibility, learner experience (LX).

The Transformational Use of Video in Online Learning

Rapidly changing and ubiquitous technologies, including mobile devices, free online tools, social networks and instant connectivity, have fundamentally changed the ways people interact, socialize and learn (Casares, Dickson, Hannigan, Hinton, & Phelps, n.d.; Milrad & Spikol, 2007). A recent University UK (2012) report noted that access to, adoption of and attitudes toward the application of technology in online learning in higher education continues to grow and evolve. However, the acceptance and use of technology is often limited to administrative and management improvements (University UK, 2015; Brown & Johnson, 2015). A systemic shift in pedagogy from the “content + discussion + assignment model” (Janssens-Bevernage, 2015) has yet to happen. An NMC Horizon Report noted that “rewarding teachers for innovative and effective pedagogy [is] a wicked challenge — one that is impossible to define, let alone solve. Many institutions provide more incentives for research over exemplary teaching” (Brown & Johnson, 2015, p. 1).

Changes Impacting Online Learning: Affordance, Connectivity, and Attitudes

Distance learning, in existence since the first correspondence course was offered in 1728, has experienced exponential growth at the beginning of this century due in large part to the creation of online technologies such as learning management systems (LMS), cloud storage and file sharing sites (Miller, 2014). Unfortunately, this technology mainly serves to support administrative tasks, making current practices more efficient but doing little to change pedagogical practice (Bates & Sangra, 2011; Siemens & Tittenberger, 2009). Massive open online courses (MOOCs) offered both inside and outside universities are a good example of how MOOCs leverage technology to effectively scale online course distribution to thousands, even tens of thousands, of participants but fail to take advantage of the ability of technology to create connected communities or design interactive learning opportunities (Holton, 2012). The results are low student engagement and very low completion rates (MOOC Research Initiative, 2014).

Along with the rapid development of these formal uses of technology for learning came the growing ability to informally network, share, and learn (Brown & Johnson, 2015; Collin, Rahilly, Richardson, & Third, 2011). At the same time, the availability of sophisticated do-it-yourself (DIY) video, photography, and publishing tools led to an explosion of readily available open content and put consumption, curation, creation, and choice into the learners’ hands (Siemens & Tittenberger, 2009; Sinclair, McClaren, & Griffin, 2006). Moreover, with the recent advent of smartphones and high-speed data access, learners can now share, create and learn anywhere, anytime, on any device (Contact North, 2016; Irvine, Code, & Richards, 2013; Milrad & Spikol, 2007). Where the former tools often served to replicate existing practices, these new tools have the potential to disrupt previous norms (Brown & Johnson, 2015; Casares et al., n.d.; Christensen, Horn, & Johnson, 2008).

Together, these changes have fundamentally shifted learners’ expectations and needs (Casares et al., n.d.; Irvine et al., 2013). Today’s learners seek a “high touch,” personalized learning experience that includes less formal and more social interactions and environments, “humanized” instructors, and options and choice in resources and learning materials (Siemens & Tittenberger, 2009; Sinclair et al., 2006). Unfortunately, though there are pockets of exciting innovation (Brown & Johnson, 2015; Fullan & Donnelly, 2014), most online learning represents a lateral shift in content and methodology involving transmissionist rather than participatory instruction (Barab, Merrill, & Thomas, 2001; Irvine et al., 2013).

The course I’m taking has longer videos (6-20 minutes) of the instructor mumbling as he draws over and over on ever increasingly confusing PowerPoint slides. Basically, the course is taught as if I was sitting in a class watching an instructor draw on a PowerPoint — the fact that it’s running in a web browser and can provide a different method of teaching seems to be lost on the instructor (Holton, 2012).

Technology’s role in education is generally that of a tool; it tends to replicate existing practice rather than act as a change agent to transform it (Puentedura, 2013). The use of cumbersome, “locked-down” LMSs reinforce traditional top-down instruction in direct opposition to the demand for more open, flexible, interactive, and informal learning environments (Bass, 2012; Bates & Sangra, 2011). At the same time, students still require guidance, direction, and feedback (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000; Ke, 2010) within a collaborative community focused on deep learning. As Garrison (2007) noted, “Interaction and discourse plays a key role in higher-order learning but not without structure (design) and leadership (facilitation and direction)” (p. 7). This dichotomy of wants and needs challenges us to re-examine current instructional methods and technology use and re-imagine and redesign online learning.

Video: A Vehicle, an Influencer, and a Catalyst

Video is one ubiquitous technological tool and medium at our disposal. Both familiar and excitingly new, video is an excellent catalyst for change. When intentionally designed, produced, and curated, video amplifies what works and helps transform current practice to better address the unique expectations, abilities, and needs of today’s learners. Like other more recent technologies, some predicted that moving pictures would revolutionize learning from video’s inception.

“Books,” declared the inventor with decision, “will soon be obsolete in the public schools. Scholars will be instructed through the eye. It is possible to teach every branch of human knowledge with the motion picture. Our school system will be completely changed inside of ten years” (Thomas Edison as cited in O’Toole, n.d.).

Edison’s prediction fell short. Video is just one of many examples of how new technology has been used to maintain or replicate existing practice. Video’s potential for change wasted. While it is easier than ever to personally create, upload, and share videos, it still remains a mainly transmissionist medium, at best augmenting current methodologies. In Siemens and Tittenberger’s Handbook of Emerging Technologies for Learning (2009) the authors recognized that media such as video is both a vehicle to deliver instruction and an influencer of the ways learners represent and process information (p. 21). However, Siemens and Tittenberger’s (2009) recommendation to, extend the use of lectures by “…enabling learners to view missed (or not fully understood) lectures at their convenience” (p. 46), is more augmentation than transformation. This simple improvement inserts video into the existing structure of online learning without considering what new tasks, processes or strategies the technology supports that were before inconceivable (Puentedura, 2013, 5:35 sec.).

With this question, a third role for video emerges: that of catalyst or change agent. As Pea (1985) noted, technology, when used in different ways for different purposes, has the potential to restructure or reorganize how we think, process, and learn. Rather than just replacing or amplifying the process, instruction or content, catalysts “…open up new possibilities of thought and action,” and the technology “…becomes an indispensable instrument of mentality and not merely a tool” (Pea, 1985, p. 175).

Three Lenses to Examine and Transform the Use of Video in Online Learning

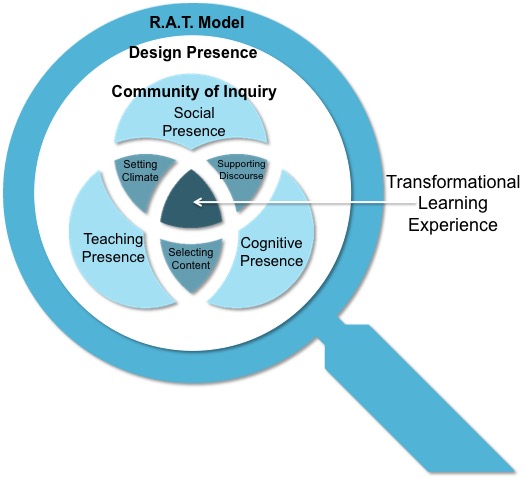

Supporting the transformation of video in learning requires a series of lenses to examine the intentional use of video as a catalyst. Figure 1 represents the three lenses that aid in this transformational process:

- The replicate, amplify & transform (RAT) model (Hughes, Thomas and Scarber, 2008) is used as an assessment framework to support the transformation of instructional practice.

- The community of inquiry (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 2000) is created by the intersection of cognitive, teaching and social presence and is used to create collaborative environments for deep learning.

- The design presence is a combination of production, accessibility and aesthetic principles that help ensure a quality product (video) and support a positive learner experience (LX).

Figure 1. Three lenses to examine the transformative process of technology in course design & delivery

Figure 1. Three lenses to examine the transformative process of technology in course design & delivery

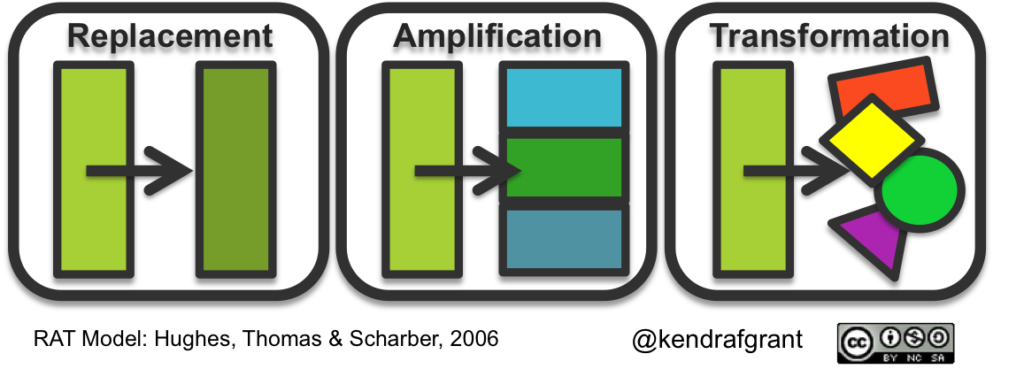

Replication, amplification, transformation (RAT). The RAT framework (Hughes et al., 2008) is a useful guide when examining technology’s purpose within a learning context. This simple 3-part model acts as a lens to help frame the role of video in online course development by focusing on three actions: replacement, amplification and transformation. Beyond using new technology to do old things, the RAT model challenges us to consider what is now possible that was previously inconceivable (Puentedura, 2013).

Figure 2. Replacement, Amplification & Transformation Model

Figure 2. Replacement, Amplification & Transformation Model

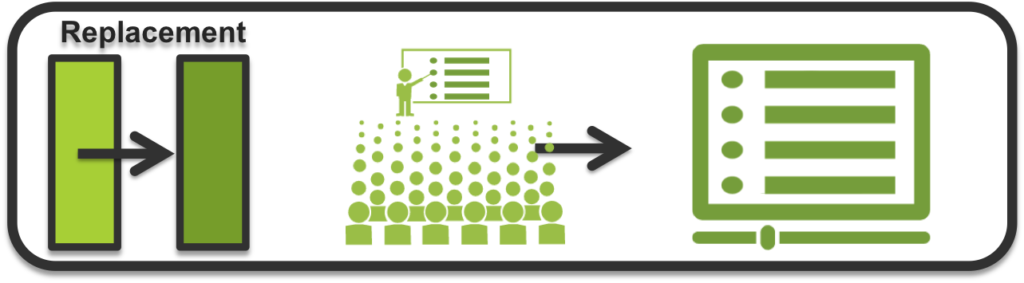

The first level is replacement. At this level, there is no change in teaching and learning, only lateral movement as content slides from one medium to the next. For example, presentation slides may be transferred to video, or a lecture may be videotaped. At the replacement level, no consideration is given to how the technology might change the instructional process, the learning outcomes or the students’ learning or roles (Hughes et al., 2006).

Figure 3. Replacement – Live lecture becomes video lecture

Figure 3. Replacement – Live lecture becomes video lecture

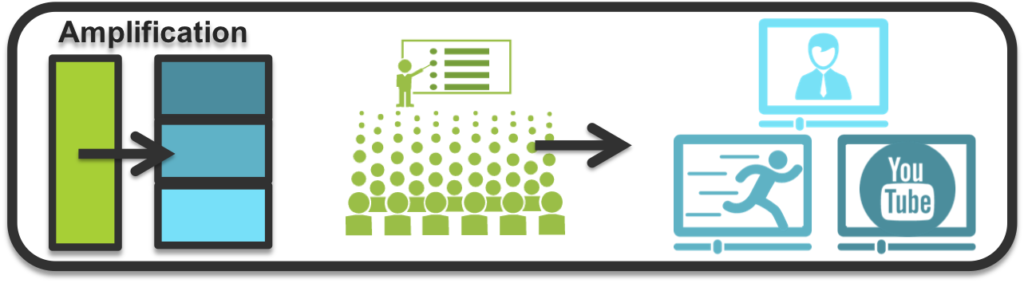

The second level is amplification. At this level, technology increases efficiency and productivity with minimal change to teaching practice, student learning, or curriculum goals. Often, the process is made more efficient or effective through a “first-order change” where only surface features are affected. For example, combining several types of video – e.g., talking head, animation, YouTube content – can make a video more engaging for the learner. At the amplification level, the bells and whistles of the technology are embraced, but a change in instructional practice has yet to occur.

Figure 4. Amplification – Lecture enhanced with a variety of video formats

Many of the innovations, particularly those that provide online content and learning materials, use basic pedagogy – most often in the form of introducing concepts by video instruction and following up with a series of progression exercises and tests. Other digital innovations are simply tools that allow teachers to do the same age-old practices but in a digital format. While these innovations may be an incremental improvement such that there are less cost, minor classroom efficiency and general modernization, they do not, by themselves, change the pedagogical practice of the teachers or the schools (Fullan & Donnelly, 2013, p. 25).

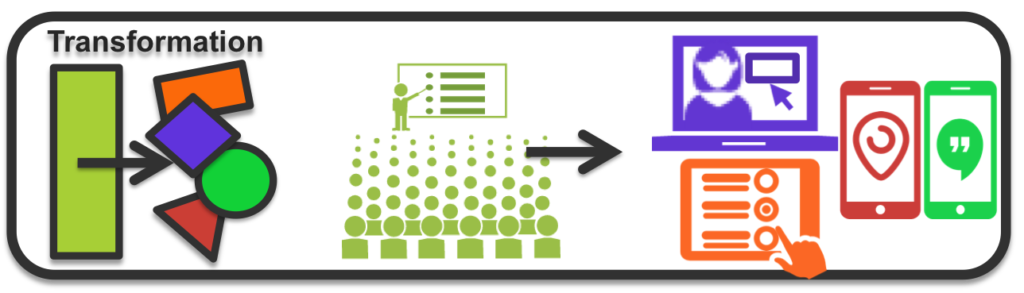

Figure 5. Transformation – Interactive, personalized learning experiences

Figure 5. Transformation – Interactive, personalized learning experiences

The final stage is transformation. At this level, the technology allows for forms of instruction and learning that were previously unimaginable (Puentedura, 2013). For example, video chat supports and builds collaborative communities, interactive video personalizes learning through options and choice, and DIY tools (e.g., screen capture or quick cell phone videos) provide immediacy and the “human” touch so important to online learning.

While no level of the RAT model is “bad,” the goal is to move towards transformation. The RAT model encourages us to think through our reasons for using a given form of technology, in this case, video, and examine why we are using it the way we are and how we might use it differently. This high-level view acts as a frame of reference as we design for deep learning within a community of inquiry.

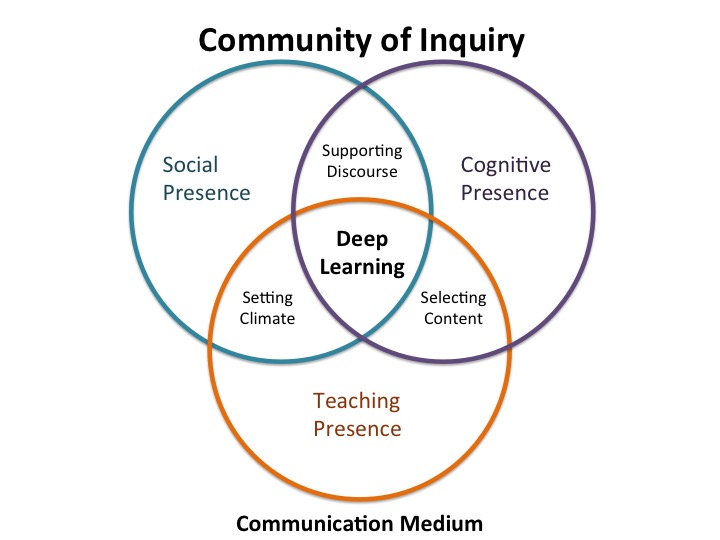

Community of Inquiry

The community of inquiry (CoI) theoretical framework (Garrison et al., 2000) “…represents a process of creating a deep and meaningful (collaborative-constructivist) learning experience through the development of three interdependent elements – social, cognitive, and teaching presence” (Community of Inquiry Model, n.d., para. 2). This second lens closely examines video’s function in helping to establish and build the three presences that promote deep engagement, learning, and commitment to learning. “Reaching beyond transmission of information and establishing a collaborative community of inquiry is essential if students are to make any sense of the often incomprehensible avalanche of information characterizing much of the educational process and society today.” (Garrison et al., 2010, p. 95)

Figure 6. Community of inquiry model (Koole, 2013)

Social Presence

Social presence is “the ability of participants in a community of inquiry to project themselves socially and emotionally, as ‘real’ people (i.e., their full personality), through the medium of communication being used” (Garrison et al., 2000, p. 94). Given the ease of video creation, video is an excellent communication tool for online instruction that can help build social presence. Instructor-created video can “fill the communication gap and closely simulate the presence experience in face-to-face classrooms” (Stoerger, 2012, p. 168). A short introductory video, in which the presenter briefly shares his or her bio and personal information, helps to quickly establish instructor presence and sets the conversational tone of the course (Scollins-Mantha, 2008). This brief introduction to the instructor’s personality encourages students to form a social connection with the instructor (Borup, West, & Graham, 2012; Stoerger, 2013).

Humour is an important aspect of social presence that helps decrease social distance and acts “…like an invitation to start a conversation” (Gorham & Christophel as cited in Garrison et al., 2000, p. 100). However, not everyone is a comedian. Failed attempts at humour can be avoided through the inclusion of humorous sayings, images, or cartoons. Humour, when connected to key ideas or course concepts (see Figure 7), promotes critical thinking and supports cognitive presence as it builds social presence through laughter (Scollins-Mantha, 2008).

Figure 7. Get more blisters to win more debates (Hagy, 2016)

Beyond the creation of social video, the inclusion of additional short videos, such as a website tour, course overview, weekly check-in or personal feedback, helps to reduce participant confusion and sense of aloneness by clarifying tasks and deadlines, supporting learning and providing options to connect (Borup et al., 2012; Stoerger, 2013). Videos also give the instructor an opportunity to share his or her thoughts and reflections, outline expectations, model desired communication and sharing behaviours, and frame his or her role as collaborator and guide (Scollins-Mantha, 2008).

Teaching Presence

Teaching Presence “…is the design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes (Anderson, Rourke, Garrison, & Archer, as cited in Community of Inquiry Model, para. 4). The use of short 1-2 minute videos throughout the course is an excellent way of communicating beyond text-based posts and builds teaching presence. Often more clear and concise than a formally typed response, video can be used to answer questions in detail or to post thoughts, reflections, or comments directly to the class or to individual participants. Online screen capture tools, such as Screenr (Articulate, 2016) and Screencast-O-Matic (Screencast-O-Matic, 2016), are ideal for quick explanatory or instructional videos, and a self-recorded phone video is an easy way to respond quickly to students. Responding by video helps build students’ sense of instructor immediacy, an effective tool that supports both social and teaching presence (Jones, Kolloff, & Kolloff as cited in Stoerger, 2013).

The inclusion of video chats and webinars is an additional way to build teaching presence (Garrison et al., 2000). These virtual face-to-face meet-ups are opportunities to encourage more informal discussion where individual questions can be answered. Additional communication tools such as polls, sidebar chats and share features further support participation and engagement. Google Hangouts (Google, 2016a) and Skype (Microsoft, 2016) limit the number of video participants and are best suited for small group meetings or virtual office hours where students drop in to ask a question and discuss ideas. Hangouts on Air (Google, 2016b) and other webinar tools like Adobe Connect (Adobe, 2016) and GoToWebinar (Citrix, 2016) allow for larger numbers of participants and have built-in recording options. These video check-ins provide “the instructor with an opportunity to clarify misunderstandings, address questions that surfaced during the week, and present related materials that could supplement the students’ understanding” (Stoerger, 2013, p. 170). With webinar type meet-ups, however, exercise caution. Unless planned to be shorter and more conversational, webinars often replicate lengthy one-way lectures. The use of the chat feature, enabling the microphone for questions or the creation of a Twitter backchannel using a unique hashtag provides authentic opportunities to converse. The Twitter conversation, summarized using a tool such as Storify, and the webinar video can then be shared as an asynchronous resource.

Streaming video tools also help build teaching presence. Free video streaming apps such as Meerkat (Life on Air, 2016) and Periscope (Twitter, 2016) allow anyone to broadcast live to the world. Students can join via the app or on social media. The apps can be used to share an event, experiment, interview, or guest speaker on location in real-time. Students can respond by adding their questions and thoughts to the recording. The instructor can “acknowledge or even respond to these comments out loud on the live broadcast to encourage engagement and make the experience feel like more of a two-way conversation” (Webb, 2015, p. 1). These broadcasts are then saved for asynchronous viewing for those who could not attend.

Cognitive Presence

Cognitive Presence “is the extent to which learners are able to construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse” (Community of Inquiry, n.d, para. 5). Video is often used as a unidirectional medium with information flowing from the expert or instructor to the learner. To move from transmission of content to construction of knowledge, tools such as Voice Thread (VoiceThread, 2016) support asynchronous conversation in a multimedia format. After the instructor uploads a short video presentation, learners use a variety of media to comment, respond, and reflect. This format, when designed with open-ended questions, serves as a springboard for lively discussion and further inquiry. When used in reverse, with the instructor providing feedback and support to student uploads, both cognitive and social presence is enhanced (Borup et al., 2012).

The Horizon Report (2015) notes that flipped classrooms are on the horizon for higher education. In the current construct of a flipped classroom, learners view a video before class and use class time to apply what they learned. This represents amplification since current practice is enhanced not transformed. An instructor can “double flip” the classroom by providing access to lectures after students explore, investigate, determine their own questions and build their own conceptual understanding. First, present students “with a challenge and then [have them] learn what they need to know to address the challenge” (Bass, 2012). After students view the lecture, they can identify, analyze, and share their faulty thinking to determine gaps and decide on the next steps in their learning.

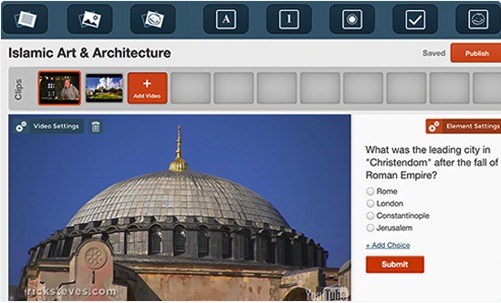

Interactive video is another form of video with the potential to transform learning. These tools create a web experience within the medium of video. As with all new technology, the tendency to replicate practice is always present. With a tool such as Zaption (Zaption, 2016), instructors can include pop-up problem-based and open-ended questions to encourage analysis and inquiry rather than fact-based and lower order comprehension questions to test recall. As of September 30th, 2016 Zaption was acquired by Workday. An alternate site to Zaption is Vizia. See Figure 8 for an example.

Figure 8. Example of lower order thinking and replication of practice using new technology (Zaption)

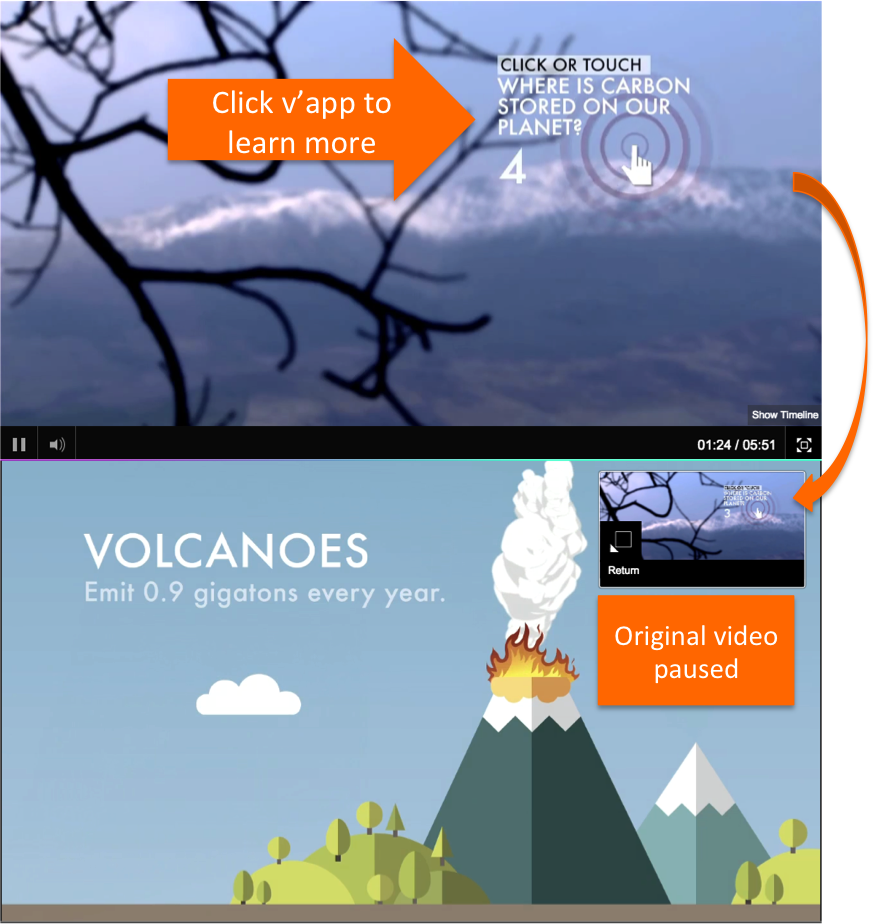

TouchCast (TouchCast, 2016) is a slightly different tool that provides the video creator with the ability to personalize learning through the use of video apps (v’apps) embedded in the video. V’apps, such as links, polls, checklists, Google docs, maps, video and links, customize the learning experience by providing options and choice. The learner can choose whether or not to click or tap the v’app as it appears in the video. If a viewer chooses to access the v’app, he or she then investigates, learns more, watches another video, takes a poll, answers a question or reflects on the topic, all while remaining in the original paused video (Figure 9). This rich interactive learning experience allows the learner to choose when and how deeply to engage in learning. “By adding interactivity, you turn a passive activity into an active one. You deepen your learners’ engagement—and create opportunities to go deeper into the content” (Articulate, 2014, p. 11).

Figure 9. Video apps (v’app) inside TouchCast deepen and extend learning though exploration and choice (BBC, 2015).

Video has the potential to transform learning when its use expands beyond content delivery. As noted, video supports deep learning within a community of inquiry when intentionally designed to build social, teaching, and cognitive presence. However, video’s role in the construction of online presence can be greatly reduced when a fourth and equally vital presence, digital presence, is missing.

Design Presence

Design presence is an intentional process that combines the technical aspects of production with accessibility and aesthetic principles. Design presence builds online presence and reduces friction, a term associated with web design and defined as “anything that prevents a user from reaching a goal” (Cao, 2015, para. 1). Given its importance, it is interesting to note that design presence was rarely considered or applied until recently.

While it’s well understood that good curriculum design is foremost, and we know a lot about learning from research in the field of education…it’s not yet on many people’s radar how critical visual and multimedia design are to success. Despite the fact that there’s plenty of evidence for its influence…the front-end can still fall victim to old school prejudices that the visual design is mere decoration or not a serious contributor to the experience (Peters, 2011, p. 1).

Design presence acts as both glue, cementing the other three presences together, and oil, reducing the friction that causes learners to disengage and disconnect when their learning experiences do not match their needs. Design presence is vital in online learning. When the course interface – layout, navigation, interactions (Peters, 2011) – and materials, images, video, print (Schaffhauser, 2015) – are designed with production, aesthetic, and accessibility principles in mind, the learning experience is greatly enhanced. Without design presence, even the most transformative instructional experience can be lost.

When all four presences are intentionally planned and implemented, it helps ensure a good user experience or, as Vander Ark (2014) refers to it, learner experience (LX). It is easy to recognize when something is poorly designed. It may be difficult to pinpoint the exact design flaw, but we know our experience is less than optimal. This is especially true with video. While video helps establish, direct and maintain a CoI, poorly produced video interferes with cognition, communication, or engagement and quickly leads to a negative LX.

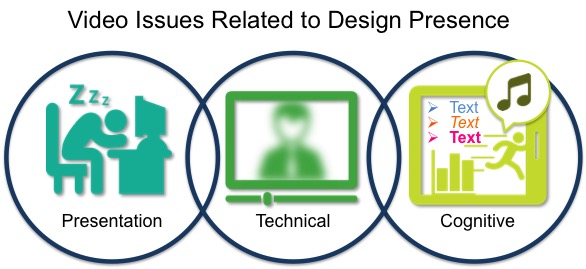

Video production issues that interfere with learning. There are three issues related to the production of video that impede design presence: presentation, technical and cognitive issues (Figure 10). Learners rarely watch or retain information from a poorly produced video, and any number of issues can be the cause (Clark & Mayer, 2011; Dirksen, 2015). While video does not need to be professionally created (students viewed instructors who personally produced videos as more authentic and human; Stoerger, 2013), a video with a mumbling presenter, grainy video or poor editing is often difficult to watch or finish.

Figure 10. Three video production issues that interfere with engagement and learning

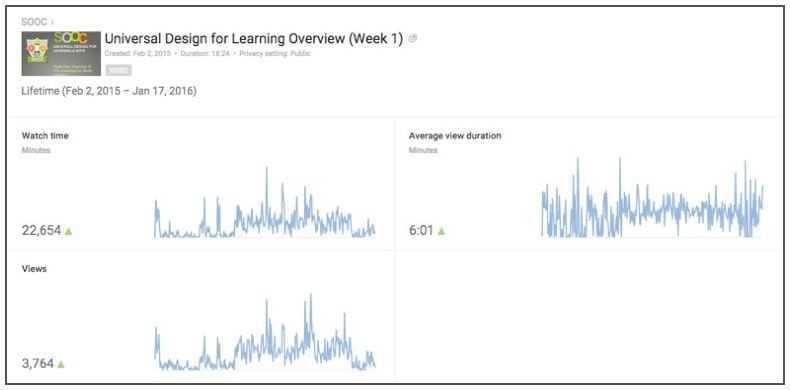

Presentation issues. Before correcting video problems, it is important to determine if videos are watched and for how long. The only production issue may be video length. If videos are stored within an LMS or on a YouTube channel, viewing analytics are available that provide data related to the number of views and, more importantly, how long the video was viewed (Figure 11). In one study (Camp, 2013), half the viewers were gone at the 60-second mark. While these statistics reflect all aspects of video viewing including entertainment, viewing time emphasizes the need for brevity. Learners prefer short, concise videos with a personal feel (Guo, Kim, & Rubin, 2014). One can continue to create hour-long videos, but duration may contribute to viewer disengagement; courses that rely on long videos may lead students to disengage from the course as a whole (Holton, 2012; Stoerger, 2013).

Figure 11. Example of viewing analytics for YouTube Video

Analyzing and addressing presentation issues is a quick and easy way to improve design presence. Issues such as mumbling or rambling, a presenter’s movement or behaviours, the ubiquitous “flying” cursor in how-to videos or scribbling over a slide detract from the video’s intended purpose (Clark & Mayer, 2011). When creating video, it is important to consider it a performance that will, when finished, become a permanent learning object, living forever online. As such, the creation of a script before filming is essential. This is standard practice in video production and is crucial to the creation of a quality product. Scripts help eliminate delivery problems such as long pauses, repetition, and rambling. While beginning with a script may feel counterintuitive, it is important to note that even the most informal of professional videos are scripted (Wistia, 2015). It can also be very helpful, if somewhat counterintuitive, to record the script before filming the video. Recording the audio first helps ensure the voiceover is smooth and natural without the pauses, repetitions, or errors that commonly occur when one’s focus is divided between speaking and interacting with the computer while filming (Wistia, 2015). Reading from a script need not be formal or stiff. A relaxed informal conversation is preferred, supporting both social and cognitive presences (Borup et al., 2012).

Therefore, using conversational style in a multimedia presentation conveys to the learners the idea that they should work hard to understand what their conversational partner (in this case, the course narrator) is saying to them. In short, expressing information in conversational style can be a way to prime appropriate cognitive processing in the learner (Clark & Mayer, 2011, p. 184).

Once complete, an audio file then acts as a guide during video production, helping eliminate erratic movements, scribbling on slides, and other visual problems that often occur when audio and video are produced together (Wistia, 2015).

Technical issues. The second issue focuses on capturing high-quality audio and video and eliminating post-production errors. In the video Choices (Barrett, 2010), the professor shares insights into her personal and professional choices. It is heartfelt but there are many issues with production and post-production, including blurry images, unclear audio, and out of sync narration and images. The viewer has to extend great effort to attend to, finish, or learn from the video.

Avoiding technical issues requires careful attention to the environment and equipment (Wistia, 2015). Problems such as improper lighting, microphone feedback or static, background noise, an unsteady video cam or blurry images all impact the quality of the final product. When learners focus on extraneous features, it interferes with the processing of important information (Clark & Mayer, 2011) as well as engagement with the instructor (Bondareva, Meesters, & Bouwhuis, n.d.). A quick video test to identify any technical problems is a good first step.

Post-production, intended to clean up production errors such as audio static or narrator mistakes, can also add issues when poorly executed. Editing programs, such as iMovie (Apple, 2016), Camtasia (TechSmith, 2016), ScreenFlow (Telestream, 2016), and YouTube (Google, 2016c), offer many editing options, including syncing audio and video, editing video length, adding music, adding callouts or transitions, using the Chroma key (green screen) and uploading the finished product. Learning to edit takes time and commitment but provides a layer of polish to personally created videos that help to remove friction from the viewing experience.

Cognitive issues. Clark and Mayer’s (2011) book, E-Learning and the Science of Instruction, explores six principles based on the cognitive theory of multimedia learning. They focus on research-based instructional methods that reduce cognitive load and support the “mental processes [that] transform information received by the eyes and ears into knowledge and skills in human memory” (Clark & Mayer, 2001, p. 39). Clark and Mayer challenge the assumption that media-rich courses are automatically mind-rich. They examine how the use and placement of multimedia elements either support or reduce learning. While not all of their suggestions are applicable to video, their work highlights the need to use text, images, audio, and animation with understanding and the intent to optimize learning.

Rather than using words on their own, the multimedia principle suggests using words (printed text or narration) and graphics (both static drawings, charts, graphs, maps, or photos and dynamic animation or video; Clark & Mayer, 2011, p. 67). In video production, this means eliminating bulleted presentations, such as narrated PowerPoint slides. In place of bulleted presentations, Clark and Mayer suggest the inclusion of purposeful graphics and animations that support the ideas and concepts explored through the narration.

Related to this, the coherence principle addresses the extraneous use of images and sounds. Put simply, avoid eye and ear candy (Clark, 2013). Only include images necessary for understanding and supported by the narration, and only cautiously include music. Music that fades away as the narration begins captures attention, but continuous music throughout a narrated video is distracting and overloads working memory (Clark & Mayer, 2011, p. 153).

The redundancy principle asserts that the use of audio or text is better than the use of audio and text when explaining on-screen graphics. The redundancy effect occurs when the combination of a visual with text and repetitive narration overwhelms working memory. Clark and Mayer (2011) suggest there are special situations where on-screen text is permissible, such as when students are learning English or they have learning disabilities (p. 141). However, this principle should be ignored when it comes to the addition of closed captioning.

Accessibility. Creating a learning environment, task or resource that is inaccessible, difficult to access or requires requests to accommodate creates unnecessary barriers for learners (Dalton, Grant, & Pérez, 2015). No technology, resource or medium is perfect. It is important to be aware of personal preference for certain forms such as text as well as built-in barriers that exist in all forms including video. While video is an excellent medium for learning, it too may be inaccessible to some. Where possible, provide learners with multiple access options (Meyer, Rose, & Gordon, 2013). Within video, this includes the addition of closed captioning and access to video transcripts. Subtitles (to support English language learners [ELL]) and Described Video (DV) are important options, although these may require professional support to create.

Research shows the inclusion of closed captions and subtitles support comprehension and engagement in students with learning disabilities and ELL (Evmenova, 2008). Beyond students with learning differences and in contrast to Clark & Mayer’s (2011) work, Gernsbacher (2015) noted in her review of over 100 research studies that captions improve comprehension, memory, and attention for everyone. Like most aspects of the Universal Design for Learning (Rose, Meyer, & Gordon, 2013), a framework that addresses learner variability from the outset is essential for some but beneficial for all (Gernsbacher, 2015).

Similarly, faculty and administrators in higher education are unlikely to be aware of the benefits of captions for university students, despite the fact that captions perfectly illustrate the fundamental principle of Universal Design. Like curb cuts and elevators, captions were initially developed for persons with disabilities, and, like curb cuts and elevators, captions benefit persons with and without disabilities (Gernsbacher, 2015, p. 198).

Generating closed captions, especially with the creation of a script, is a simple “copy, paste, sync” process inside a tool such as YouTube. While some organizations rely on automatically generated captions, such as those available on YouTube, it is not recommended. The unfortunate results of automatic captions are seen all too often (Figure 12).

Figure 13. Examples of automatic closed captioning

Aesthetic principles. “Good design is about effective communication, not decoration at the expense of legibility” (Friedman, 2010, para. 32). Although the tools to create content are readily available and relatively simple to use, skill and planning are required to create aesthetically pleasing materials. As more and more instructors create their own materials, the need to understand the elements of good design is essential to maximizing learning (Schaffhauser, 2015). Poorly designed resources and materials can easily mar an instructionally well-designed course (Peters, 2011; Schaffhauser, 2015). When designing any learning experience or resource, it is always important to ask the question: “Will [my students] learn something in spite of the way this was designed or because of it?” (Peters, 2011, para. 12).

Not all videos require strict adherence to aesthetic principles. Quickly created explanatory and check-in videos with attention to production and accessibility are often sufficient when expediency is required. However, videos that include visual elements such as images, diagrams, graphs, text, or animation require a focus on aesthetics. Given that most instructors are not designers, the application of basic design principles helps create a pleasing design that also supports learning.

The arrangement of video elements is essential for a beautiful and effective layout that also supports cognition. Careful alignment and spacing of images and text provide an organized and pleasing visual structure that supports understanding (Clark & Mayer, 2001, p. 91). Meanwhile, the use of white or empty space around images and text emphasizes important information (Clark & Mayer, 2011, p. 173) and makes the text easier to read.

Simplicity in design is recommended. A white background with the inclusion of a small logo (placed consistently in the same location) is enough to brand a video while eliminating distracting designs and images that must be unnecessarily processed by the learner (Clark & Mayer, 2011, p. 173). The same is true for fonts. While it may be tempting to include an unusual or unique font, the use of a basic font type such as Helvetica, Courier, Arial, or Verdana is easier to read and still pleasing to the eye, especially for students with learning disabilities or those with vision problems (Marshall, 2013). Choice of text can even affect motivation, one study found that “if directions are presented in a font that is deemed more difficult to read, such as Times New Roman…the task will be viewed as being difficult, taking a long time to complete and perhaps, not even worth trying” (Song & Schwarz as cited in George, 2010a, para. 8).

As noted earlier, images greatly increase learner understanding if used correctly. If an image is unrelated to the content or purely decorative, it can be confusing; the brain tries to process and associate the image with other available contextual elements to make meaning (Clark & Mayer, 2011, p. 131). Pictures also elicit an emotional response and, when used effectively, support memory and engagement, but grainy or poor quality images can generate a negative response (Gutierrez, 2014). When choosing images and photos, determine if they are necessary, then ensure they are high quality and evoke the intended emotions.

As with all elements, color can either support or distract the learner. The influence of color on mood and decision-making is well documented. Research has noted that decisions (to buy, to watch) are largely based on color choice (WebpageFX, n.d.). Choosing two colors from a personal or institute logo is a simple way to determine a color scheme. The use of a dark text color is preferred as dark text provides contrast (dark text on a light background) which is both visually appealing and more accessible to those with dyslexia, low vision, or colorblindness (George, 2010b). The inclusion of a third color (either from the logo or a complementary color from the opposite side of the color wheel) can be used to highlight or signal key points for the learner (Clark & Mayer, 2011, p. 40).

The visual design of a video is important for a variety of reasons. It is not just an enhancement of content or a decoration. As noted throughout this chapter, a video that looks and sounds professional reduces friction. The background, logo and images, font and colors, chosen can add or detract from the video’s intended use, reduces social, teaching, and cognitive presence. In addition, aesthetically pleasing videos set the standard for a course, acting as an exemplar for the quality and commitment expected from students when they create and share their own projects, papers, and videos.

Conclusion

We live in the spur of the moment, in the kingdom of “micro-moments” (Google, n.d.). How people access information, connect with others and learn has fundamentally and irrevocably changed. Today’s online learner expects a more informal, interactive, and social experience while also requiring opportunities to collaboratively construct deep understanding. This is a challenge in a skim and scan world where the focus is fleeting and memory is often held on a device. For the most part, higher education has struggled to address the changing needs of learners and take advantage of the ability affordance of new technology to transform current practice. In this chapter, we explored how one familiar technology, video, acts as a vehicle, influencer and, most importantly, a catalyst to implement the required changes.

Most online environments continue to rely on the transmission of knowledge through video lecture, replicating and reinforcing existing practices and ignoring the multimedia savvy learner. This generation of learners expects the inclusion of multimedia but not in the form of lecture (Bart, 2011). Regardless of a presenter’s skills, online learners rarely find long talking-head or text-heavy recorded slide presentations engaging. As such, while video lectures still have a role in online learning, video offers much more than the means to transmit content. Video can open up a realm of possible constructivist activities that engage the learner, deepen the learning, and support a robust CoI.

To promote this process, a three-part lens should be used to examine and frame the use of video. The first lens is the RAT model which encourages progressively more constructivist, hands-on, and minds-on learning enabled by technology. Rather than replicate or incrementally improve what was done before, the RAT model focuses on change. Video, rather than remain a vehicle for content delivery or even an influencer of cognitive processes, can become a catalyst for change in pedagogy, roles, and learner agency.

The second lens focuses on the development of a community of inquiry. The CoI model acknowledges that social, teaching, and cognitive presence are needed for learners to flourish online. Video plays many roles in the development of a community of inquiry. Video can build social presence by presenting the personal side of the instructor. It supports teaching presence by promoting ongoing conversation and personalized feedback. It also strengthens cognitive presence when used in innovative ways beyond the traditional lecture. When applied across all three presences, video moves teaching and learning into the transformational level of the RAT model.

The final lens is design presence. Digital presence is achieved through attention to production, aesthetics, and accessibility with the intent to guide, support, and improve learning. Design presence is not just superficial enhancement; it is a vital component of a frictionless LX that successfully supports social, teaching, and cognitive engagement.

Video is not new, but the ability of individuals to create, re-purpose, and share video effortlessly and with everyone, is. As video continues to evolve through the addition of virtual and immersive video environments, three-dimensional capabilities and augmented reality, the focus needs to remain on how these tools can challenge us to embrace change and create learning environments that meet the needs of all learners. With the proper commitment, attention, and innovation, video and other technology can transform the education landscape.

References

Adobe. (2016). Adobe Connect. [Online software]. Retrieved from http://www.adobe.com/products/adobeconnect.html

Anderson, T., & Dron, J. (2011). Three generations of distance education pedagogy. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning,12(3), 80-97.

Apple. (2016). iMovie (Version 2.2.1) [Mobile application software]. Retrieved from https://itunes.apple.com/ca/app/imovie/id377298193?mt=8

Archibald, D. (2013). An online resource to foster cognitive presence. In Z. Akyol & R. Garrison (Eds.), Educational communities of inquiry: Theoretical framework, research, and practice (pp. 168-196; Google Books version). Retrieved from https://books.google.com

Ark, T. V. (2014, December 27). It’s time to invest in learning design [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://gettingsmart.com/2014/12/time-invest-learning-design/

Articulate. (2016). Screenr [Online software]. Retrieved from https://www.screenr.com/

Articulate. (2014). The secret to creating great elearning videos [PDF version]. Retrieved from http://www.articulate.com

Barab, S. A., Merrill, H., & Thomas, M. K. (2001). Online learning: From information dissemination to fostering collaboration. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 12(1), 105-143. Retrieved from https://sashabarab.org/

Barrett, H. (2010, July 27). Choices [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CHMUwdUCXiM

Bart, M. (2011, November 16). The five R’s of engaging millennial students [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-and-learning/the-five-rs-of-engaging-millennial-students/

Bates, A. W., & Sangrà, A. (2011). Managing technology in higher education: Strategies for transforming teaching and learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

BBC (Producer). (2015). Bitesize masterclass No. 2 [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/taster/projects/bitesize-geography

Bass, R. (March 21, 2012). Disrupting ourselves: The problem of learning in higher education [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://er.educause.edu/articles/2012/3/disrupting-ourselves-the-problem-of-learning-in-higher-education

Belmudez, B., & Möller, S. (2013). Audiovisual quality integration for interactive communications. EURASIP Journal on Audio, Speech, and Music Processing, 2013(24), 1-23. doi:10.1186/1687-4722-2013-24

Bondareva, Y., Meesters, L., & Bouwhuis, D. (2006). Eye contact as a determinant of social presence in video communication. In M. Nael (Chair), Multimodal, multi-device, context dependent systems, services and applications. Symposium conducted at the meeting of Human Factors in Telecommunication, Sophia-Antipolis, France. Retrieved from http://www.hft.org/HFT06/paper06/37_Bondareva.pdf

Borup, J., West, R. E., & Graham, C. R. (2012). Improving online social presence through asynchronous video. The Internet and Higher Education, 15(3), 195-203. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.11.001

Brecht, H. D. (2012). Learning from online video lectures. Journal of Information Technology Education: Innovations in Practice, 11, 227-250. Retrieved from http://www.informingscience.org/Journals/JITEIIP/Overview

Brown, M., & Johnson, L. (2015). NMC horizon report: 2015 higher education edition. Retrieved from https://www.uakron.edu/dotAsset/dd1dfebe-b663-486b-908c-51bd704fb7ac.pdf

Camp, N. (2013, May 8). Online video attention span – How long should a video production be? [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.thevideoeffect.tv/2013/05/08/online-video-attention-span-how-long-should-a-video-production-be/

Canva. (n.d.). Graphic design tutorials. Retrieved from https://designschool.canva.com/tutorials/

Cao, J. (2015, March 8). How to reduce friction with good design [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://thenextweb.com/dd/2015/03/08/how-to-reduce-friction-with-good-design/

Casares, J., Dickson, D., Hannigan, T., Hinton, J., & Phelps, A. (n.d.). The future of teaching and learning in higher education (Version 13). Retrieved from Rochester Institute of Technology website https://www.rit.edu/provost/sites/rit.edu.provost/files/future_of_teaching_and_learning_reportv13.pdf

Christensen, C. M., Horn, M. B., & Johnson, C. W. (2008). Disrupting class: How disruptive innovation will change the way the world learns. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Citrix. (2016). GoToWebinar [Online software]. Retrieved from http://www.gotomeeting.com/webinar

Clark, D. (2013, January 17). Mayer & Clark – 10 Brilliant design rules for e-learning [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://donaldclarkplanb.blogspot.ca/2013/01/mayer-clark-10-brilliant-design-rules.html

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2011). E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Community of Inquiry. (n.d.). CoI model. Retrieved from https://coi.athabascau.ca/coi-model/

Collin, P., Rahilly, K., Richardson, I., & Third, A. (2011) The benefits of social networking services: A literature review. Retrieved from Western Sydney University website: http://www.uws.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/476337/The-Benefits-of-Social-Networking-Services.pdf

Dalton, E., Grant, K., & Perez, L. (2015). Improving the MOOC: Developing the short (and supportive) open online course model. In M. Chitiyo, G. Prater, L. Aylward, G. Chitiyo, P. Haria, & E. Dalton (Eds.), New Dimensions Toward Education, Advocacy and Collaboration: Proceedings of the 14th Biennial Conference of the International Association of Special Education (pp. 58-60).

Dirksen, J. (2015). Design for how people learn (2nd ed.). Berkeley, CA: New Riders.

Edge Studio. (2015). Script timer – Words to time calculator. Retrieved from http://www.edgestudio.com/production/words-to-time-calculator

Evmenova, A. (2008). Lights! Camera! Captions!: The effects of picture and/or word captioning adaptations, alternative narration, and interactive features on video comprehension by students with intellectual disabilities. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://kihd.gmu.edu/

Friedman, V. (2010, May 4). The current state of web design: Trends 2010 [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2010/05/web-design-trends-2010/

Fullan, M., & Donnelly, K. (2013). Alive in the swamp, assessing digital innovations in education. London, England: Nesta.

Gardner, K., & Aleksejuniene, J. (2011). PowerPoint and learning theories: Reaching out to the millennials. Transformative Dialogues: Teaching & Learning Journal, 5(1), 1-11. Retrieved from https://www.kpu.ca/td

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61-72. Retrieved from http://onlinelearningconsortium.org/read/journals/

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. doi:10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

George, A. (2010a, May 04). ELearning & mLearning: In fonts we trust [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://iconlogic.blogs.com/weblog/2010/05/elearning-in-fonts-we-trust.html

George, A. (2010b, June 21). ELearning & mLearning: Using color in learning, part II [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://iconlogic.blogs.com/weblog/2010/06/elearning-mlearning-using-color-in-learning-part-ii.html

Gernsbacher, M. A. (2015). Video captions benefit everyone. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2, 195-202. doi:10.1177/2372732215602130

Google. (2016a). Google Hangouts [Mobile application software]. Retrieved from https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.google.android.talk&hl=en

Google. (2016b). Hangouts on Air [Online software]. Retrieved from https://plus.google.com/

Google. (2016c). YouTube [Online software]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/

Google. (n.d.). Micro- moments. Retrieved January, 2016, from https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/micromoments/intro.html

Grant, K. (2015, October 31). Closed captioning [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xfzKPXnAZ3k

Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014). How video production affects student engagement. Proceedings of the First ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale Conference – L@S ’14, 41-50. doi:10.1145/2556325.2566239

Gutierrez, K. (2014, July 8). Studies confirm the power of visuals in elearning [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://info.shiftelearning.com/blog/bid/350326/Studies-Confirm-the-Power-of-Visuals-in-eLearning

Hagy, J. (2016, January 8). Get more blisters to win more debates [Image]. Retrieved from http://thisisindexed.com/2016/01/get-more-blisters-to-win-more-debates/

Holton, D. (2012, May 5). What’s the “problem” with MOOCs [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://edtechdev.wordpress.com/2012/05/04/whats-the-problem-with-moocs/

Hughes, J., Thomas, R. & Scharber, C. (2006). Assessing technology integration: The RAT – replacement, amplification, and transformation – framework. In C. Crawford, R. Carlsen, K. McFerrin, J. Price, R. Weber & D. Willis (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2006 (pp. 1616-1620). Chesapeake, VA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Irvine, V., Code, J., & Richards, L. (2013). Realigning higher education for the 21st-century learner through multi-access learning. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(2), 172-186. Retrieved from http://jolt.merlot.org/

Janssens-Bevernage, A. (2015, December 30). Musings on completing a PBL MOOC about PBL (problem-based learning) [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://dynamind-elearning.com/2015/12/musings-on-completing-a-pbl-mooc-about-pbl-problem-based-learning/

Ke, F. (2010). Examining online teaching, cognitive, and social presence for adult students. Computers & Education, 55, 808-820. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2010.03.013

Kirschner, P. A. (2002). Cognitive load theory: Implications of cognitive load theory on the design of learning. Learning and Instruction, 12, 1-10. doi:10.1016/S0959-4752(01)00014-7

Koole, M. (2013, February 13). The community of inquiry model comprised of three overlapping circles representing social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence [Image]. Retrieved from https://coi.athabascau.ca/coi-model/coi_model_small/

Life on Air. (2016). Meerkat [Mobile application software].

Marshall, A. (2013, August 22). Good fonts for dyslexia – An experimental study [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://blog.dyslexia.com/good-fonts-for-dyslexia-an-experimental-study/

Meyer, A., Rose, D., & Gordon, D. (2013). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice [Electronic version]. Retrieved from http://udltheorypractice.cast.org/login

Microsoft. (2016). Skype [Online software]. Retrieved from http://www.skype.com/en/

Miller, G. (2014, November 10). History of distance learning. Retrieved from http://www.worldwidelearn.com/education-articles/history-of-distance-learning.html

Milrad, M., & Spikol, D. (2007). Anytime, anywhere learning supported by smart phones: Experiences and results from the MUSIS Project. Educational Technology & Society, 10(4), 62-70. Retrieved from http://www.ifets.info/

MOOC Research Initiative. (2014). Grantee final reports. Retrieved from http://www.moocresearch.com/reports

Morrison, D. (2012, January 16). What is online presence? [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://onlinelearninginsights.wordpress.com/2012/01/16/what-is-online-presence/

Oblinger, D., & Verville, A. (1999). Information technology as a change agent. Educom Review, 34(1). Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/search/apachesolr_search?filters=tid:33160

O’Toole, G. (2012, February 15). Books will soon be obsolete in the schools. Retrieved from http://quoteinvestigator.com/2012/02/15/books-obsolete/

Paul, A. M. (2014, August 20). Informal education: What students are learning outside the classroom. Hechinger Report. Retrieved from http://hechingerreport.org/informal-education-students-learning-outside-classroom/

Pea, R. D. (1985). Beyond amplification: Using the computer to reorganise mental functioning. Educational Psychologist, 20(4), 167-182.

Peters, D. (2011). Say hello to learning interface design [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://uxmag.com/articles/say-hello-to-learning-interface-design

Puentedura, R. R. (2013, January 07). Technology in education: A brief introduction [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rMazGEAiZ9c

Schaffhauser, D. (2015, November). 8 best practices for moving courses online [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://campustechnology.com/Articles/2015/02/11/8-Best-Practices-for-Moving-Courses-Online.aspx?Page=1

Scollins-Mantha, B. (2008). Cultivating social presence in the online learning classroom: A literature review with recommendations for practice. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning, 5(3), 2. Retrieved from http://www.itdl.org

Siemens, G., & Tittenberger, P. (2009). Handbook of emerging technologies for learning. Retrieved from http://elearnspace.org/Articles/HETL.pdf

Sinclair, G., McClaren, M., & Griffin, M. (2006). E-Learning and beyond (Discussion Paper). Retrieved from https://app.box.com/shared/8cfx5cfbpi

Screencast-O-Matic [Online software]. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.screenr.com/

Stoerger, S. G. (2013). Using video to foster presence in an online course. In E. G. Smyth & J. X. Volker (Eds.), Enhancing instruction with visual media: Utilizing video and lecture capture (pp. 166-176). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

TechSmith. (2016). Camtasia [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://www.techsmith.com/camtasia.html

Telestream. (2016). ScreenFlow (Version 5.0.2) [Computer software]. Retrieved from http://www.telestream.net/screenflow/overview.htm

TouchCast. (2016). TouchCast (Version 1.4) [Mobile Application software]. Retrieved from https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/touchcast/id603258418

Twitter. (2016). Periscope [Mobile application software]. Retrieved from https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=tv.periscope.android

Universities UK. (2015). Futures for higher education: Analysing trends. Retrieved from http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Pages/futures-for-higher-education.aspx

VoiceThread. (2016). VoiceThread [Online software]. Retrieved from http://www.skype.com/en/

Webb, J. (2015, April 9). 5 quick tips for using Periscope, Twitter’s live video streaming app [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/periscope-app-live-broadcasting-tips

WebpageFX. (n.d.). The hidden meanings behind famous logo colors [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.webpagefx.com/logo-colors/

Wistia (Producer). (2015). Wistia library [Video database]. Retrieved from http://wistia.com/library

Zaption. (2016). Zaption [Online software].