6

Susan Spellman-Cann, Erin Luong, Christina Hendricks, & Verena Roberts

In this chapter we explain and discuss the value of various aspects of social learning in online environments: developing relationships, learning with and from peers, and producing work for authentic audiences. Though developing connections between learners and facilitators may seem more difficult in an online context than in face-to-face classrooms, the affordances of digital tools can still make meaningful connections possible. Another benefit of learning online is the possibility of learners creating works for authentic audiences—for people beyond just the course instructor and their classmates. If they put their work on the open web, it will reach a wider audience of practitioners in that field, or anyone else who is interested, having impacts far beyond the course itself. We discuss a particular connectivist MOOC we participated in as an example of successful engagement of online students in social learning.

Introduction

In the Community of Inquiry model, social presence is “the ability of learners to project their personal characteristics into the community of inquiry, thereby presenting themselves as ‘real people’” (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 1999, p. 89). It also refers to participants’ ability to engage meaningfully in a community, through developing interpersonal relationships that allow them to communicate openly and freely. According to Garrison and Vaughn (2008), students in a community of inquiry must feel free to express themselves openly in a risk-free manner. They must be able to develop the personal relationships necessary to commit to, and pursue intended academic goals and gain a sense of belonging to the community (Chapter 2, para. 15).

A successful community of inquiry is an environment in which participants feel safe expressing their true thoughts and feelings, where they have a sense of social cohesion and they collaborate on shared projects. Social presence also involves expressing emotions: presenting ourselves as “real people” in a community means we are interacting with others on an emotional level as well a cognitive one.

We, the authors of this chapter, have had numerous successful experiences of social presence in online courses, having had the chance to express ourselves and interact with others as “real people,” making lasting connections that are beneficial to all involved. In such courses, we have engaged in social learning: learning with others in this sort of supportive, collaborative community. Social learning activities include developing relationships amongst participants and between participants and instructors, peer learning, and engaging with authentic audiences beyond the course. We explain these activities below and discuss a particular case study as an example of successful social learning: a Connectivist MOOC we all participated in during 2013, called ETMOOC (Educational Technology MOOC).

Social Learning Online: The Importance of Relationships

Bandura has long held the importance of social learning. Bandura’s work on self-efficacy (1989) examined how humans cope, how much energy will be expended and how much time will pass as they change behaviours in order to persevere. Human interaction helps support self-efficacy. Human connection is as important today as it was long ago. “Over the past decade, social media has evolved from being an esoteric jumble of technologies to a set of sites and services that are at the heart of contemporary culture” (Trowler, 2010). Online environments make social connections even more important as instructors do not have the opportunity to meet with their students face to face in a classroom. Online students often feel isolated, which may decrease motivation and increase attrition. When learning occurs entirely through computer-mediated instruction, an important part of the instructor’s role is ensuring the learning environment is “people focused” or humanized (Dupin-Bryant, 2005). So how can instructors humanize online experiences so that each individual gets a rich learning experience allowing for interconnectedness and an interactive, positive learning environment?

Relationships are as important online as they are off. Relationships increase student engagement, which stimulates learning (Trowler, 2010). In their literature review of the factors that have a high impact on student success, Kuh et al. (2008) explain that interactions between peers can positively impact student learning, self-esteem, and persistence. Such beneficial interactions include not only working together on academic projects or participating in class discussions but also engaging with other students socially and in extracurricular activities. It may seem challenging to foster connections between learners in the online context, but rather than using four physical walls as a classroom, the online learning instructor has the opportunity to gather their community in various forms of virtual spaces that can also be effective for developing relationships. Boyd (2014) describes virtual gathering spaces as “networked publics,” which are both “(1) the space constructed through networked technologies and (2) the imagined community that emerges as a result of the intersection of people, technology, and practice” (p. 8). She goes on to say that “as spaces, the networked publics that exist because of social media allow people to gather, connect, hang out, and joke around” (p. 9). This can happen not only within the “space” of the class such as a course website but also in social media, which can take on the role of fostering out-of-class social connections.

Online interactions can be more challenging than those that occur face-to-face, however, because there can be less information to guide them. Students in a face-to-face classroom use body language to convey some aspects of their thoughts and feelings, and to monitor how others react to them. In an online learning environment such immediate feedback is not available, so we must be conscious of the online social presence that we choose to portray. It is important to pay careful attention to what we say and do, and how, especially considering that online interactions may not include communication in the form of body language and tone of voice. Weiss (2000) provides some useful suggestions for trying to replicate such visual and auditory cues in online, text-based interactions such as stating directly when one is making a joke or using emoticons. Still, some of what we convey may be unintentional: “What we convey to others is a matter of what we choose to share in order to make a good impression and also what we unintentionally reveal as a byproduct of who we are and how we react to others” (Boyd, 2014, p. 48).

To help build cohesiveness of a group it is important for instructors/facilitators to monitor the e-tone (mood) of a discussion and model an attitude of acceptance and inquiry. By monitoring the tone of a discussion/twitter/chat, an instructor can gain valuable insight into the dynamics of the group. Instructors/facilitators should be encouraged to model responses that demonstrate respect, tentative language, and curiosity since these qualities project an attitude of acceptance for alternative ideas.

Connections between learners are important, but so are connections between learners and instructors. Authenticity matters, so when an instructor is perceived as a real person who engages with their students and creates a personal connection, students are more likely to learn and enjoy what they are learning (Rourke, Anderson, Garrison & Archer, 2001). Kuh et al. (2006) point to numerous research studies that show the value of student-teacher interaction for student engagement, success, and satisfaction. Both in-class and out-of-class interactions are valuable. In online courses, students often interact with teachers through discussion boards, blog posts and comments, social networks such as Twitter, and more. One important way for instructors to connect with students in an online context is through the use of video: it’s much easier to feel that one is interacting with a human being when one can see and hear them rather than only reading text. So having instructors introduce themselves through a video can be a great way for students to have a better sense of whom they’re working with, in the course. Instructors might also consider sharing some information about their personal lives (such as hobbies outside of the classroom) to facilitate connections. Asking students to create videos to introduce themselves might also be a good thing to try, depending on the context of the course.

Learning from and with Peers

Boud (2001) describes peer learning as “a two-way, reciprocal learning activity. It should be mutually beneficial and involve the sharing of knowledge, ideas and experience between the participants. It can be described as a way of moving beyond independent to interdependent or mutual learning” (p. 3). Boud (2001) also notes several benefits for students of learning with peers, such as learning how to work with others to achieve shared goals, and gaining a better understanding what they do and do not understand through discussing their knowledge and responding to questions or challenges from others (p. 8-9). We can also think of peer-to-peer learning as “peeragogy,” which, according to The Peeragogy Handbook v. 3, is “a flexible framework of techniques for peer learning and peer knowledge production” (Rheingold et al., 2013, p. 9). Whereas “pedagogy” has to do with “the transmission of knowledge from teachers to students, peeragogy describes the way peers produce and utilize knowledge together” (Rheingold et al., 2015, p. 9).

One might think that those with less knowledge would be the ones who mainly benefit from peer learning, but those who are sharing their knowledge with others can do so as well; as many teachers already recognize, a great way to learn something is to try to teach it to others. Peer learning can take many forms, such as formal group projects, assignments requiring students to engage in discussion, or informal, student-led study sessions. Online, peer learning can occur on discussion boards, comments on blog posts, collaborative projects, synchronous audio or video chats, social media, and more.

Peer learning can be particularly useful when it comes to using online tools. Students who are novices at using technology may limit their contributions because they lack confidence in their ability to use the system. It is important that facilitators not take ownership for providing answers to all technical concerns. Rather than solving all issues, facilitators should guide their students towards the correct path (White, 2004). Encouraging students to consult and support their peers helps to provide technical support and develops positive group cohesiveness (Luong, 2006).

Authentic Audiences and Students as Producers

Bass and Elmendorf (n.d.) have a somewhat different definition of social learning than what has been discussed so far. They define what they call “social pedagogies” as “design approaches for teaching and learning that engage students with what we might call an “authentic audience” (other than the teacher), where the representation of knowledge for an audience is absolutely central to the construction of knowledge in a course” (Bass & Elmendorf, n.d.). They emphasize the value of learners making connections to audiences beyond just the teacher, providing information and using their skills to benefit others in and often beyond the class: “Ideally, social pedagogies strive to build a sense of intellectual community within the classroom and frequently connect students to communities outside the classroom” (Bass & Elmendorf, n.d.). In this way, social learning can include students connecting not just with each other and with their instructors, but with the wider public. According to Bruff (2011), “ Social pedagogies provide a way to tap into a set of intrinsic motivations that we often overlook: people’s desire to be part of a community and to share what they know with that community.” Bruff lists several ways to involve students in creating for authentic audiences, such as through contributing to a public blog, curating lists of public web bookmarks, and collaborating on shared documents.

Closely connected to this view of social learning is the “student as producer” educational model, which contrasts with the usual view of students as consumers of knowledge. According to Neary (2014), the student as producer approach emphasizes “the role of students as collaborators with academics in the production and representation of knowledge and meaning” (p. 1). In so doing, it “aims to radically democratize the process of knowledge production” (Neary and Winn, 2009, p. 201). This approach treats learners as producers “within the University,” “of the University and of the curriculum,” and “beyond the University” (student as producer). This, too, involves students not just producing knowledge for their instructors, but for other students and those outside the class as well. Derek Bruff (2013) explicitly makes this link between students as producers and sharing work with authentic audiences, creating knowledge that is of value to others inside and beyond the classroom.

Social learning, then, can include forging connections among students, between students and instructors, and between the classroom (virtual or physical) and the wider online community.

Social Learning in Connectivist MOOCs

Allowing people to truly connect instead of just watching a video and answering questions (as many online courses do) could lead to making online learning a more humanized experience. We see this emphasis on connecting participants in “connectivist” MOOCs, or cMOOCs. Key concepts in connectivist moocs include: sharing, communication, collaboration, building knowledge, social, support/help, variety in learning experience, fun, connection, autonomy, and flexibility (Bates, 2014). These dynamic, learner-centric communities bring participants together under the guidance of facilitators. They help participants focus not only on the topics they are exploring but on the process of gaining the most from each other as members of learning communities.

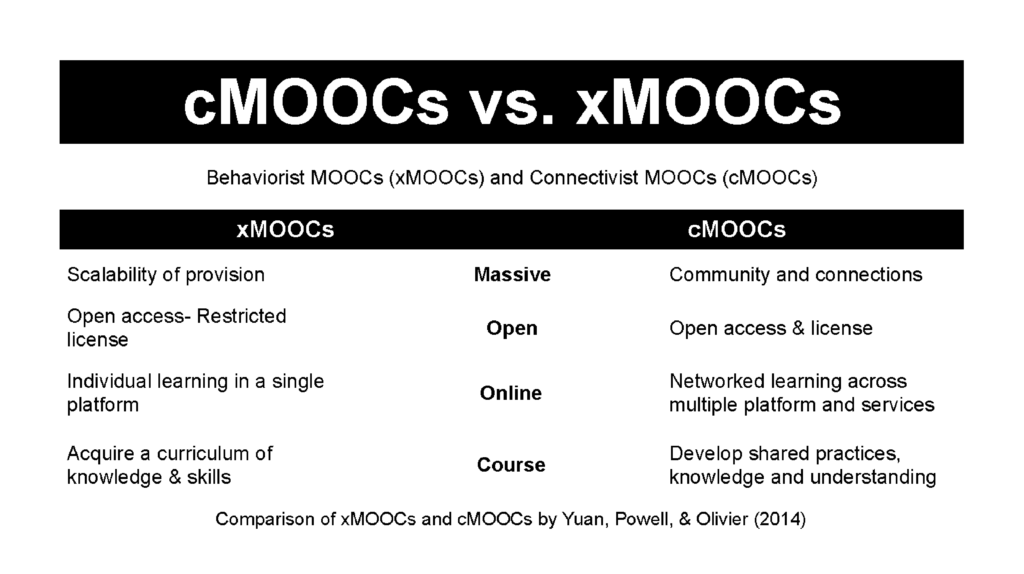

cMOOCs have often been contrasted with “xMOOCs,” which use the model of the teacher as the expert providing content that the students must learn and be tested on (see here for an explanation by Stephen Downes of what the “x” stands for in “xMOOCs”). Yuan, Powell & Oliver (2014) provides a nice overview of the differences between cMOOCs and xMOOCs, and the slide below shows some of these.

Table 1: xMOOCs vs. cMOOCs; This table is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Bates (2014) lists the main features of xMOOCs and cMOOCs, and states that while xMOOCs “primarily use a teaching model focused on the transmission of information” from an expert to students, cMOOCs focus on peer learning:

cMOOCs . . . primarily use a networked approach to learning based on autonomous learners connecting with each other across open and connected social media and sharing knowledge through their own personal contributions. There is no pre-set curriculum and no formal teacher-student relationship, either for delivery of content or for learner support. Participants learn from the contributions of others, from the meta-level knowledge generated through the community, and from self-reflection on their own contributions (Bates, 2014).

It is perhaps more accurate to say that, at least in some cMOOCs, there is a minimal pre-set curriculum. The facilitators offer some resources for reading and watching, but much of the content and curriculum of the course comes through the participants’ own work. What gets discussed, which topics are focused on during various parts of a course is only loosely determined by the facilitators; the participants are welcome to move off in different directions, raise different issues, provide different resources. In that sense, the participants are producers of the curriculum. As Cormier (2008) puts it in his description of the “rhizomatic” model of education, the “community acts as the curriculum”: “In the rhizomatic model of learning, curriculum is not driven by predefined inputs from experts; it is constructed and negotiated in real time by the contributions of those engaged in the learning process.” Further, because cMOOCs often take place on public websites, even people who are not officially participating in the courses can benefit from what participants produce as they co-construct the curriculum.

The “connectivist” part of cMOOCs comes from a learning theory called “connectivism,” with somewhat different versions having been developed by George Siemens and Stephen Downes. According to Siemens (2005), “learning is a process of connecting specialized nodes or information sources,” and so “nurturing and maintaining connections is needed to facilitate continual learning.” We learn by making connections, such as between ideas, between ourselves and sources of information, and between people. Similarly, Downes (2007) says that “[a]t its heart, connectivism is the thesis that knowledge is distributed across a network of connections, and therefore that learning consists of the ability to construct and traverse those networks.”

Connectivist MOOCs, accordingly, strive to foster connections between participants, exposing each to more ideas and resources that they can learn from. These connections can then develop into a Personal Learning Network (PLN) that lasts even after the course has been completed. Such PLNs are maintained through social media, through blog posts and comments, and through synchronous online video or Twitter chats. One may also collaborate with members of one’s PLN on various projects.

Is social learning important? We think so. How important might be debatable to some, however when comparing cMOOC’s to xMOOC’s the authors would much rather a cMOOC anytime.

An Example of Successful Social Learning Online: ETMOOC

The authors of this chapter were involved in a wonderful social learning environment, a cMOOC in 2013 called ETMOOC: Educational Technology Massive Open Online Course. This course used a “students as producers” model of pedagogy: students were encouraged to produce things for authentic audiences outside the class, to contribute to the world of knowledge in a greater way than handing in assignments only to the teacher (Bruff, 2013). We found that instructors who actually worked at developing connections and relationships with others created an environment where participants were willing to connect, learn from each other and continue to collaborate, share resources and maintain a community long after the course had finished. Dr. Alec Couros, the lead instructor for ETMOOC, and his co-conspirators skillfully facilitated ETMOOC in such a way that created meaningful connections among participants, allowing for ongoing learning and growth.

ETMOOC supported the idea of “peeragogy” as described by Rheingold et al. because we learned as much or more from each other as from the facilitators (2013). Though there were specific themes for each week of the course, most of the course content came through participants’ blogs, tweets, video logs, and more as described by Bass and Elmendorf (n.d.). In addition, throughout the course, participants, as well as facilitators shared tips on using different tech tools. See this video by Andrew Petrus for an example of how one of the participants helped others learn how to use tools like Storify and Feedly. The participants in ETMOOC reached out and to support and help others in the community, and continue to do so. It was explicitly stated in ETMOOC and OCLMOOC (another cMOOC developed by ETMOOC alumni in 2014) that everyone is welcome to participate, no matter what their ability/confidence with technology and connected learning. There will be tutorials and support for those who needed them. You are invited to participate at the level that works for you. If you want to jump in right from the start and participate in all of the activities, that is great. If you don’t have the time, or just want to lurk at first, that is fine too (Jessen, 2014).

Allowing, supporting, and encouraging learners to participate at any level creates an environment that most definitely humanizes the online experience. Many in the ETMOOC community continue to support each other, even nearly three years after the course officially ended. We know we can count on each other whenever someone needs help in understanding some technological tool, idea, or resource. Numerous participants have retained connections with each other, even having monthly video hangouts or twitter chats. This type of continuous connected and sustainable learning is what Siemens describes as “Connectivism” (2005). We organize these in our Google Plus community. Because we have developed PLN’s with several members of ETMOOC in them, a number of us have collaborated on later projects, such as designing and facilitating open online courses (OOE13, OCLMOOC), the Open Spokes vlogging group, and this chapter itself! The learning most certainly continues.

What is the real secret to online courses that are designed to work? The authors of this chapter might say “kindness.” ETMOOC co-conspirators certainly modelled kindness. They were always willing to help and encouraged all participants to help each other throughout the MOOC. The Science of Happiness, an xMOOC by EdX, devoted a whole week to the impact of kindness and compassion. Researchers have found that kindness leads to happiness (Dixon, 2011), and maybe that is why so many participants in ETMOOC have remained connected—it increased their happiness. “Being kind and generous leads you to perceive others more positively and more charitably,” writes Lyubomirsky in her book The How of Happiness, and this “fosters a heightened sense of interdependence and cooperation in your social community” (Lyubomirsky, 2010).

In ETMOOC many participants were generous with their time and kind in their actions. They demonstrated compassion in their interactions throughout the MOOC. Kindness was shown in the way that facilitators and participants helped each other by sharing their experience and expertise. Learners build trust through kind actions. Kindness really does matter in online learning. According to Lyubomirsky, as stated in the 2014 EdX course the Science of Happiness, “kindness changes the way we see ourselves: we become pillars of generosity, interconnected to those around us. We start giving people the benefit of the doubt and feel less distressed when we see suffering because we’re doing our little part to help. Kindness also helps us make more friends and become the recipient of others’ kindnesses” (Lyubomirsky, 2010). When we are kind, as was consistently demonstrated in ETMOOC, we make online learning more humanized.

Here are some of the other things that made ETMOOC such a rich social learning experience:

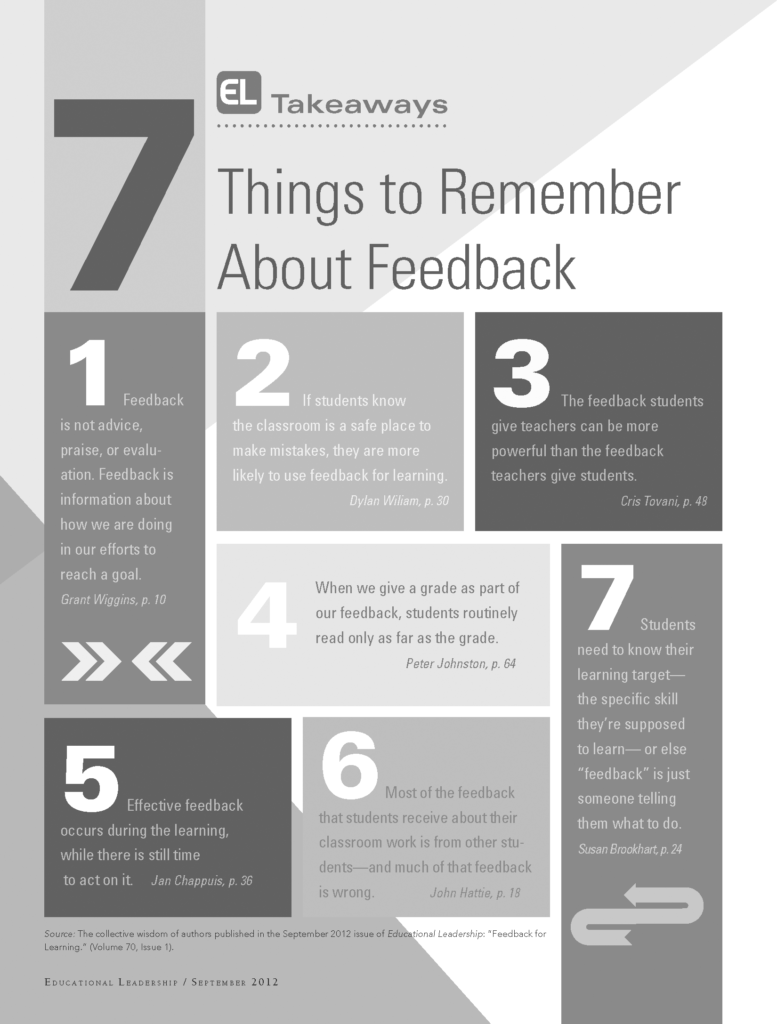

Figure 1: Feedback for Learning; Retrieved from, The collective wisdom of authors published in the September 2012 issue of Educational Leadership: “Feedback for Learning.” (Volume 70, Issue 1).The Collective Wisdom of Authors retrieved from Educational Leadership.

- The ETMOOC community developed participants’ self-efficacy skills: “Self-efficacy reflects confidence in the ability to exert control over one’s own motivation, behavior, and social environment (Carey & Forsyth, n.d.). The community provided a “safe space” such as our Google+ group and the Blackboard Collaborate sessions, where students were encouraged to question, explore, share their successes and their challenges. This “give and take” system allowed all participants to become active members of their learning communities.

- Instructors utilized social media to connect participants and made a concerted effort to connect with participants.

- A collaborative approach was taken throughout the MOOC. We were often asked to help each other with tasks, create alone or together, answer questions of other participants when needed. We were asked to work together, to not feel like we could not help each other. It was ok to help someone else within the MOOC and not wait for the co-conspirators to do it. We too could collaborate and participate with other people in the MOOC.

- Hashtags on twitter (#etmchat and #etmooc) with weekly chats and alternating Google hangouts that still continue to this day.

- A twitter archive.

- A google plus community.

- Participants were asked to blog and comment on blogs; there was a blog hub with 510 blogs in it.

- You could connect with people from all over the world.

- Videos were engaging. “Video trumps text” says Dean Shareski, so having videos that participants want to watch makes a difference.

- Facilitators allowed participants to make mistakes and set a tone that mistakes were opportunities to learn.

- There was minimal power differential between the facilitators and the students. Facilitators were also life-long learners; they both asked and answered questions with and of the participants.

- Access to learning anytime anyplace. Great courses are designed so that you get to choose when and how you learn.

- The ability to access knowledge through networks: ETMOOC encouraged the development of a PLN which created opportunities to learn at an accelerated rate.

- ETMOOC provided learners with connections to amazing teachers like Alan Levine, Dave Cormier, Dean Shareski, Doug Belshaw, Harold Rheingold, Will Richardson, Sue Waters and George Couros to name a few who modelled open and collaborative learning.

- A combination of asynchronous and synchronous activities that allowed participants from various time zones to connect and receive timely feedback on their ideas.

- Blackboard Collaborate sessions led to engaged learning where participants could be in a large space more than a hundred participants could join in and engage in the learning by writing on a whiteboard, answering a question through video or audio participation or dialoguing in a chat room within in the Blackboard session.

Another thing we found very successful in ETMOOC was starting out with a team building activity: we made a video together, the ETMOOC Lip Dub, which allowed participants to play while learning. The facilitators asked participants to create a 15-second video clip, which was then combined into a larger package and shared. The fun of creating the clips and then watching for our work in the final product is something that still brings a smile to our faces.This activity encouraged people to truly connect, and really cemented many a relationship from the beginning. The goals set out by Alec Couros for this video were most certainly met: “Let’s have fun with this! Show some of that joy and exuberance that many of you have shown thus far. I hope that this results in a great bonding experience, more familiarity with community members, and an artefact that helps to represent the experience of #etmooc” (Couros, 2013).

The power of a connectivist MOOC can be transforming, as you can see in this blog post by life-long learner Tina Photakis. Learning in a connected world can lead to a never-ending cycle of learning, says Tina Photakis in her reflective post. As Dave Cormier said when he discussed rhizomatic learning, we are all nodes in a great big growing, organic connection and the learning and creation of knowledge will continue well past ETMOOC.

“In ETMOOC which was by far my favorite MOOC so far, I know for me building trust, a sense of community, having fun, an environment that allowed for mistakes and having facilitators repeat throughout the course that mistakes were okay made a huge difference in my willingness to engage. Having instructors and fellow participants who were not only kind but practiced kindness throughout the course allowed me to flourish in an online environment. I am forever changed in a positive way because of my participation in ETMOOC. I cannot begin to tell you all the skills I have developed technologically and continue to do so, but more importantly, I believe I am a more connected, better person because of this experience. I now collaborate and continue to learn with people worldwide because of the engaging learning environment created by ETMOOC. It created in me a wonder and a passion for online learning, a yearning to make a difference online as well as providing me with an amazing professional learning network that continues to sustain and nourish me to this day “ (Susan Spellman Cann, 2015).

Does social learning matter? If you develop the right kind of community like ETMOOC did it does. The results speak for themselves. Before ETMOOC Susan and Erin did not blog, vlog, tweet, or even know what a Google+ community was. Now both connect and collaborate with educators from around the world. One of the greatest learning opportunities ETMOOC offered participants was the opportunity to develop key digital literacy skills in an authentic, collaborative, connected and supported learning environment.

Here are some other examples of the impact of social learning in ETMOOC:

- ETMOOC the power of people by Donna Miller Fry

- “We all decided to walk through the door of the internet so we could think together” by Julie Balen

- “Our voices mattered” by Glenn Hervieux

- “Love letter to ETMOOC” by Christina Hendricks

- “Unfinal reflection #etmooc” by Sheri Edwards.

In HumanMOOC another cMooc we were involved in, there were several elements that were particularly effective for connecting participants and instructors. One was the use of video; as noted above, this can be a great way to get to know people better online. In HumanMOOC, participants were asked to introduce themselves using video, and also to create sample introductory videos to use in their courses. The participants then gave each other comments on these videos, saying what worked and what could be improved. Christina found it incredibly useful to see sample introduction videos from so many people, to generate ideas for what to do for her own. Here is an example of a great introduction video by Michelle Pacansky Brock.

HumanMOOC also used Flipgrid as an easy way to have discussions through video. The facilitators raised topics for discussion, and participants used the tool to create a short video response. We also tried out VoiceThread, which allows learners to make comments on slides through video, audio, or text. Christina found that through the use of video, she was able to feel more connected to many of the participants in the course. She had interacted with some of them in the past, but only through text; seeing them on video really increased her sense of connection.

Another thing that was quite effective in HumanMOOC was that the facilitators were able to provide a significant amount of feedback on what the participants were doing. Not only were they very present in the discussion boards, but whenever participants submitted work for a badge, they got direct feedback from one of the facilitators. This can help participants feel more of a connection to facilitators, which can translate into a greater sense of engagement with the course. Clearly the larger the course the harder it is to have one-on-one feedback, but when it’s possible it can be very effective in promoting engagement.

HumanMOOC is another great example of making online learning more humanizing.

Conclusion

Though we have described an example of successful social presence and social learning in a MOOC, many of the same techniques can be used in a traditional online course as well. We have greatly benefited from the connections we made with each other, and other participants, in ETMOOC and other open, online courses we have taken. This chapter would not have happened otherwise, for example! Even online courses that are not open to the public can foster peer learning and relationships that last beyond the end of the course.

Social learning can happen purely within a course, or also with a wider audience by opening up parts of the course or some of what students create to the public. Having students produce work that is of value to other students and beyond can increase their engagement in what they’re creating and also its quality. Such open sharing can also lead to surprising and exciting outcomes at times. Alan Levine has gathered a number of videos of people describing the serendipitous outcomes of such sharing, and the connections that can result, here: http://stories.cogdogblog.com/.

Perhaps one of the most exciting aspects of social learning is the unpredictability of what can emerge when we connect with each other; many of us could not have predicted what all we would do together after completing ETMOOC. As Alan Levine says (2013), not everyone will have amazing outcomes from connections like those described in the stories he has gathered, but we will never have them if we don’t connect.

References

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American psychologist, 44(9), 1175.

Bass, R. and Elmendorf, H. (n.d.). Designing for difficulty: Social pedagogies as a framework for course design.

Bates, T. (2014). Comparing xMOOCs and cMOOCs: Philosophy and practice [Blog post]. Online Learning and Distance Education Resources.

Boud, D. (2001). Introduction: Making the move to peer learning. In D. Boud, R. Cohen, & J. Sampson (Eds.), Peer learning in higher education: Learning from and with each other (pp. 1-19). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Boyd, D. (2014). It’s complicated: The social lives of networked teens. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Bruff, D. (2011, November 6). A social network can be a learning network. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Bruff, D. (2013). Students as producers: An introduction [Blog post] http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/2013/09/students-as-producers-an-introduction/

Carey, M.P. & Forsyth, A.D. (n.d.). Teaching tip sheet: Self-efficacy. American Philosophical Association.

Cormier, D. (2008, June 3). Rhizomatic education: Community as curriculum [Blog post] http://davecormier.com/edblog/2008/06/03/rhizomatic-education-community-as-curriculum/

Couros, A. (2013). #etmooc Lipdub – “Don’t Stop Me Now.” https://docs.google.com/document/d/1iW–7ubdFdtewkYhtBTKJzzEXwMBEgrReGewC9wKgVQ/edit?usp=sharing.

Dixon, A. (2011, September 6). Kindness makes you happy . . . and happiness makes you kind. Greater Good: The Science of a Meaningful Life. http://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/kindness_makes_you_happy_and_happiness_makes_you_kind

Downes, S. (2007, February 3). What connectivism is [Blog post] http://halfanhour.blogspot.com.au/2007/02/what-connectivism-is.html

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999). Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2–3), 87–105. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Garrison, D.R. & Vaughn, N.D. (2008). Blended learning in higher education: Framework, principles and guidelines [Kindle version]. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Jessen, R. (2014). About OCLMOOC. https://oclmooc.wordpress.com/about-oclmooc/

Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Buckley, J. A., Bridges, B. K., & Hayek, J. C. (2008). What matters to student success: A review of the literature [Report]. National Postsecondary Education Cooperative.

Levine, A. (2013). Seeking your true stories of open sharing [Blog post] http://cogdogblog.com/2013/01/28/true-stories-open-sharing/

Lyubomirsky, S. (2010) Happiness for a lifetime [Videorecording]. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0EJIaTFfBss.

Morrison, D. (2013, April 22). The Ultimate Student Guide to xMOOCs and cMOOCs. MOOC News and Reviews.

McLeod, S. A. (2011). Bandura – Social Learning Theory.

Neary, M. (2014). Student as producer: Research-engaged teaching frames university-wide curriculum development. Council on Undergraduate Research Quarterly, 35(2), 28–34.

Neary, M., & Winn, J. (2009). The student as producer: reinventing the student experience in higher education. In The Future of Higher Education: Policy, Pedagogy and the Student Experience (pp. 192–210). London, UK: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Petrus, Andrew. (2013). Wading through the MOOC [Videorecording] https://youtu.be/mQs_To50HVE

Rheingold, H. et al. (2015). The Peeragogy Handbook. 3rd Ed. Chicago, IL./Somerville, MA.: PubDomEd/Pierce Press.

Rourke, L., Anderson, T. Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing social presence in asynchronous, text-based computer conferencing. Journal of Distance Education, 14(3), 51-70.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 1(2).

Student as Producer. (n.d.). University of Lincoln Educational Advancement and Development Unit http://edeu.lincoln.ac.uk/student-as-producer/.

Things to Remember About Feedback. (2012) ASCD, Educational Leadership. 70(1)

Trowler, V. (20110). Student engagement literature review [Report]. The Higher Education Academy.

Yuan, L., Powell, S., & Olivier, B. (2014). Beyond MOOCs: Sustainable online learning in institutions. CETIS White Paper.

Weiss, R. E. (2000). Humanizing the online classroom. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2000(84), 47–51.