1

Whitney Kilgore, The University of North Texas

Robin Bartoletti, The University of North Texas Health Science Center

Maha Al Freih, George Mason University

Originally published in the 2015 European MOOC Stakeholder Summit conference proceedings and republished with permission from the 2015 eMOOCS conference committee.

Abstract

In the Fall of 2013 “The Human Element: An essential online course component” was facilitated on the Canvas Open Network. Lessons the authors learned upon reflection about design, pedagogy, and research led to the second iteration: “Humanizing Online Instruction: Building a Community of Inquiry (CoI)” a 4-week Micro-MOOC made available Spring 2015. These professional development courses were designed for instructors who teach online and hybrid courses and wish to improve their online teaching practice. The courses introduced participants to the CoI framework. Participants in these networked learning experiences actively explored emerging technologies and developed digital assets that they could employ in their own online teaching practice. In this paper, the designers and instructors share experiences and lessons learned and describe efforts taken to design, develop, and evaluate the second offering of this MOOC.

Multi-Institutional Professional Development for Faculty

Increased demand for online learning options coupled with a fast evolution of technology and pedagogy necessitates an equal growth in the quality and quantity of online facilitation training for faculty to ensure effective online educational experiences (Ganza, 2012). Many online educators are using technologies that they have yet to explore in the face-to-face classroom. While advanced online and computer technologies are gradually decreasing the barriers of traditional professional development programs, instructional designers are still faced with the challenge of designing online venues for professional development based on sound design principles that take advantage of the strengths of the online medium. Using a MOOC for Professional Development allows for participants from multiple institutions and teaching across many disciplines to participate in a course together. Traditional professional development models that have existed on higher education campuses have not typically been multi-institutional.

Building a Faculty Community of Inquiry

MOOCs utilize a digital ecosystem that allows learners to self-organize around a topic of common interest. In “Humanizing Online Instruction,” a networked community of practice is created that encourages the sharing of teaching practices through blogging, tweeting, status updates, etc. Leveraging an online delivery system (Canvas.net from Instructure) for professional development reduces the participation barrier for online educators, creates a student experience from which they can explore and reflect, and develops a cross-institutional community of practice (Anderson, 2011). It is the transparent sharing and the reflecting component of the course that allows the learners to experience the power of social presence, which drives the cognitive element. Ganza (2012) states, “Reflection is the key ingredient of effective professional development” (p. 31). Based upon the model defined by Couros (2009), the facilitators will promote learning experiences that are open, collaborative, reflective, transparent, and social.

Previous Experience/ Lessons learned

The authors have developed numerous Micro-MOOCs (4-week format) since 2011. All of these courses were focused on providing professional development to educators. The strengths of these courses, as stated by the learners, have been the connections between the individual participants and between the participants and the facilitators that last beyond the actual course. This sentiment is aligned with the findings from Kop (2011) who said that the closer the ties evidenced between the people, the higher the level of presence and the higher the level of engagement in the course activities.

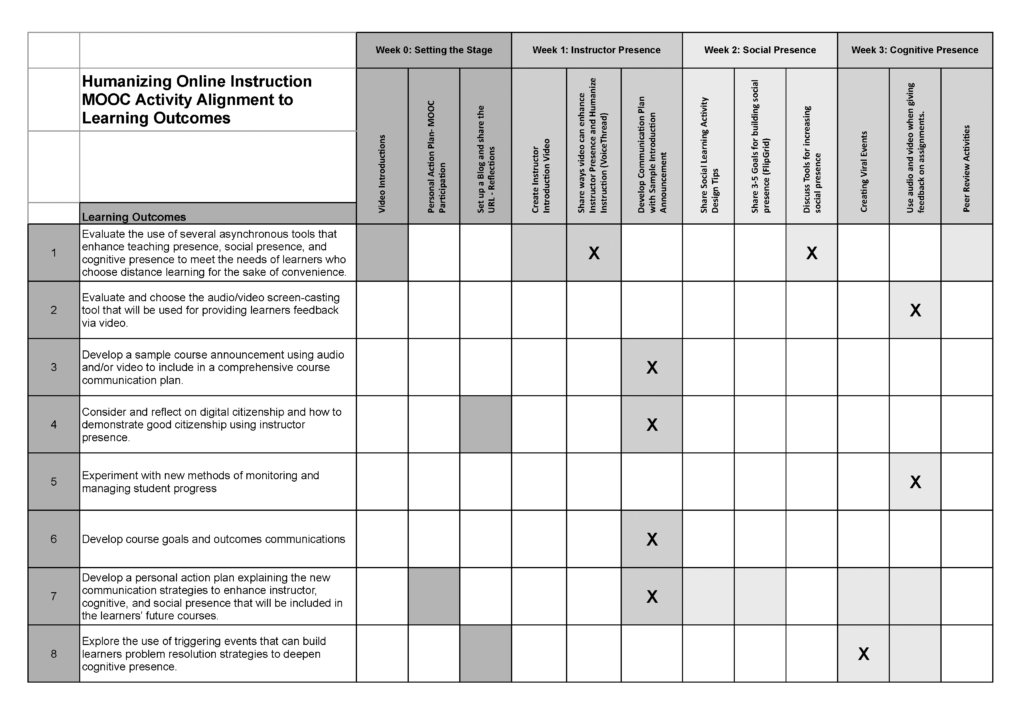

Each weekly module in the course contains annotated research and activities related to specific elements of the CoI framework (i.e. instructor, social, and cognitive presence). Building the course upon the foundation of the CoI grounded the course’s application-based activities in theory. The course began with an orientation week (Week 0) where learners prepare for the subsequent weeks by creating a blog and a twitter account if they did not yet have one, introduce themselves using video on the discussion board, and attending or watching the recorded session “Humanizing your online course” by Michelle Pacansky-Brock. The second week of the course focused on instructor (teaching) presence and the CoI in online education. Week three was centered on social presence, and the final week of the course was related to cognitive presence.

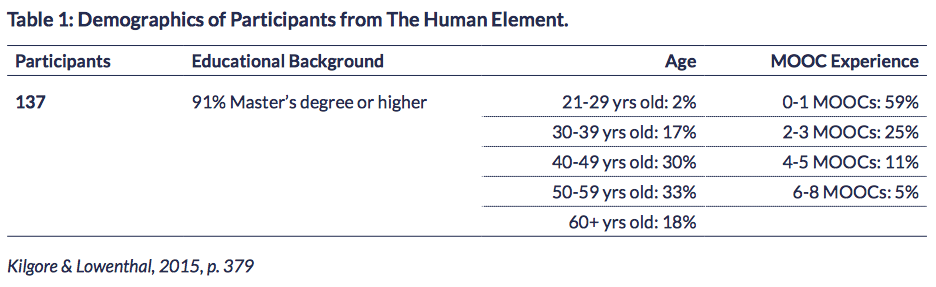

“The Human Element: An Essential Online Course Component” was taught in the Fall of 2013 on the Canvas Open Network (canvas.net). While 697 registered for the course, the course designers define participation as learners who are active in the course between the dates that the course was available online. 137 participants completed the rst survey in the course making them active course participants (Kilgore & Lowenthal, 2015). Of the 137 course participants, 50 completed the first assignment, 49 developed individualized communication goals for their own online teaching and 30 completed the course in its entirety. This means this MOOC had a 22% completion rate.

When designing “The Human Element,” the designers did not have a good sense of the potential audience for the course or their experiences and were truly designing for the unknown learner. In the course re-design, the designers used the demographics from the previous participants to inform their understanding of the potential audience. The demographic information below was collected during the first week of the course (see Table 1).

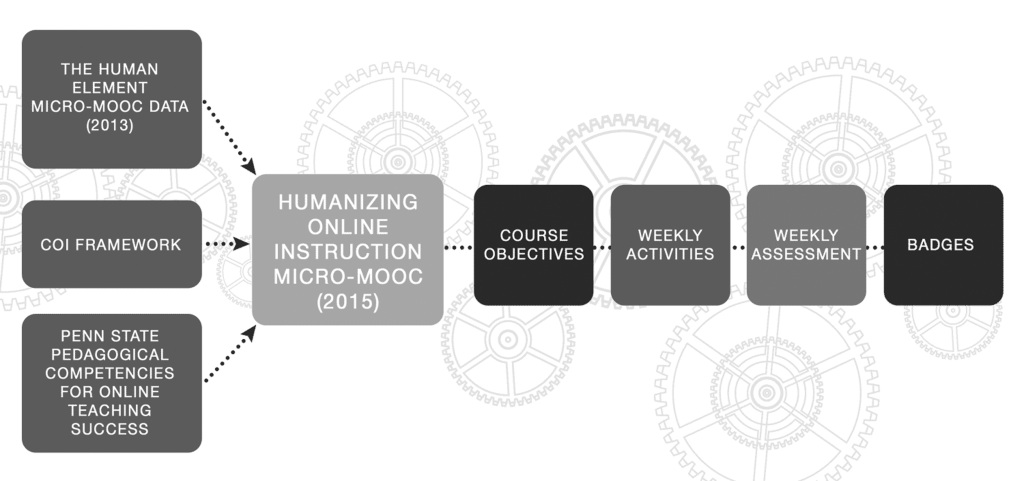

In follow-up interviews six months after the completion of the course, the participants highlight the importance of effective pedagogy, mention attempting new ways to humanize courses they design and teach, and maintain connections to people from the course. Participants shared how effective it was to learn about humanizing instruction while participating as a student. Some participants also shared negative experiences and feedback and this information was utilized in determining the approaches that could make this learning experience richer in another iteration. The comments from participants included: “I’ll admit to being a little anxious about using video in my online classes. I haven’t done it yet, but I might. One of the joys of online teaching is not having to worry about my appearance.” “Tech scares me. I don’t have a camera on my computer.”, “At one university I teach for, we record our lectures, the problem is that the field I am in changes and updating recorded lectures is a big pain.” “Sorry, can’t get the VoiceThread to record my voice for some reason – still troubleshooting.” These comments point to technical issues, varying technical proficiencies, a lack of desire to leverage recording technologies in online teaching, and issues related to content that is continually changing (Kilgore & Lowenthal, 2015). Figure 1 below is a visual representation of the redesign of the course based upon the experience of teaching the course in 2013.

Figure 1: The redesign of the HumanMOOC

Pedagogical Competencies for Online Teaching Success

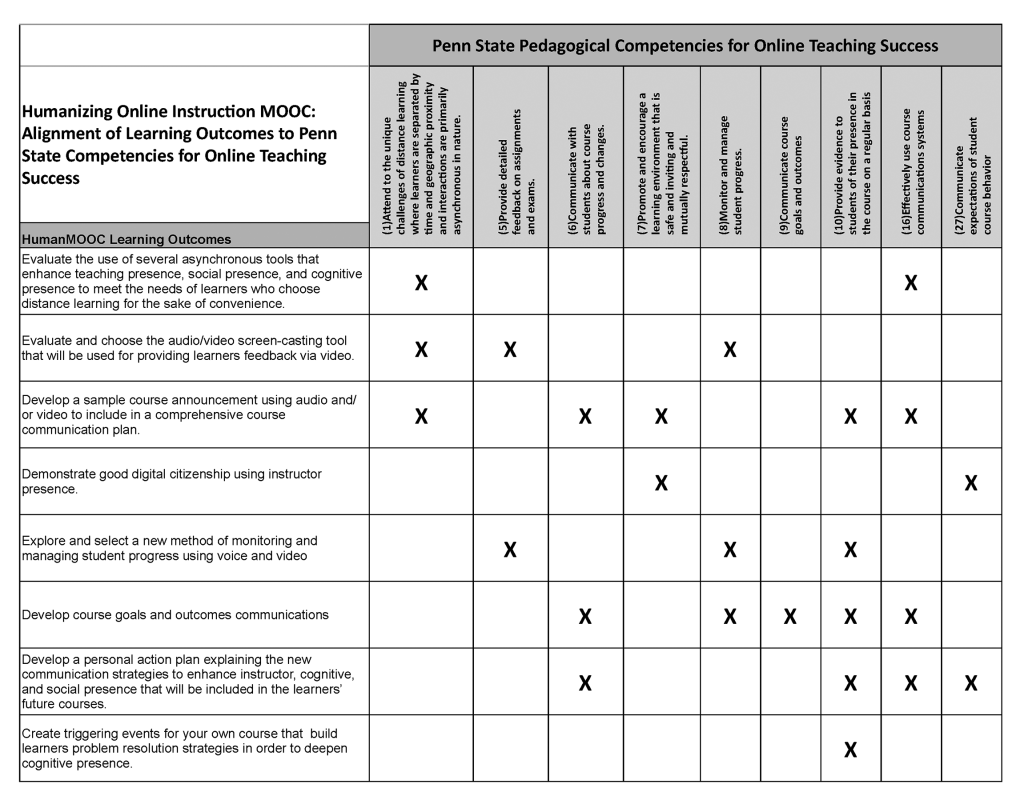

In an effort to ensure that the redesigned course would be pedagogically beneficial for faculty who teach online, the competencies for online teaching success defined by Penn State were reviewed. The Humanizing Online Instruction MOOC addresses nine of the 27 Penn State competencies. (1) Attending to the unique challenges of distance learning where learners are separated by time and geographic proximity and interactions are primarily asynchronous in nature. (2) Provision of detailed feedback on assignments and exams. (3) Communication with students about course progress and changes. (4) Promotion and encouragement of a learning environment that is safe, inviting, and mutually respectful. (5) Monitoring and management of student progress. (6) Communication of course goals and outcomes. (7) Provision of evidence to students of their presence in the course on a regular basis. (8) Effective use of course communication systems. And (9) Communication of expectations of student course behavior (Ragan, Bigatel, Kennan, & Dillon, 2012). The course learning objectives are thoughtfully crafted and aligned with these pedagogical competencies for online teaching (see Table 2).

Learning, Achievement, and Badges

Each weekly module contains authentic assessments that allowed for evaluation of learning, includes a variety of engagement opportunities including a few Google Hangouts that participants can watch live or later, and requires task completion to earn the badges for instructor presence, social presence, cognitive presence, and the CoI badge. Each week of the MOOC is designed as a stand-alone module in which participants can earn individual badges for completing specific tasks for that week (example; in week one the activities are focused on instructor presence, so the completion of the required assignments earn the participant the instructor presence badge). Those learners who elect to complete all course assignments will be eligible to earn a course completion badge known as the Community of Inquiry badge. The participants will demonstrate an understanding of the CoI, reflect on their own teaching practices, and develop an action plan to implement methods to increase teaching, social and cognitive presence in their future courses. The design of the authentic assessments ensures that learners have a strong foundation in the community of inquiry as well as ways that they can apply the principles in a very practical manner in their own teaching right away.

Table 2: Mapping Course Objectives to the Penn State Competencies

This image is best viewed online at: https://humanmooc.pressbooks.com

Activity Alignment to Learning Outcomes

Using a similar method, the learning outcomes and learning activities were reviewed for alignment. Prior to the awarding of the course badge, the designers determined through the alignment process the tasks that demonstrate the competencies that are necessary to receive each of the badges. It was discovered that many of the learning activities align to multiple standards as seen in Table 3.

Table 3: Alignment of Activities to Learning Outcomes

This image is best viewed online at: https://humanmooc.pressbooks.com

Course Design Evaluation

Prior to learners entering the newly revised course for the first time, it will undergo an extensive review. There are three steps to the formative evaluation cycle. First, the instructors who will co-facilitate the course will review and edit one module each. Next, the entire course will undergo a full review using the Continuing and Professional Education (CPE) MOOC rubric designed by Quality Matters in conjunction with EQUFEL and the Gates Foundation. The Humanizing Online Instruction MOOC reviewers are from Australia, the U.K., and the U.S. and are all qualified learning designers (master’s degree or higher in instructional design) with a minimum of 10 years of design experience. One reviewer is a certified Master Reviewer for Quality Matters and will oversee the training of the volunteer reviewers and lead the review process. After this review cycle is complete, the course will again be edited based on the feedback from the review team. These edits will ensure the course contains all of the remaining standards of the Quality Matters rubric that may have been missed in the previous development and editing process. And finally, the Canvas Network Instructional Design team will review the course before it is made available to learners.

Research Plans for the Humanizing Online Instruction MOOC

Due to the concerns raised regarding technology proficiency, the Online Learning Readiness Scale (Hung, Chou, Chen, & Own, 2010) and Stages of Adoption of Technology instrument (Christensen & Knezek, 1999) will be administered in week one of the new iteration of the course. The data from these instruments will allow us to identify participants who may require additional resources and support with technology tools during the course. Furthermore, the relatively low retention rate of MOOC participants has been a central criticism in the popular discourse. In these discussions, retention is commonly defined as the fraction of individuals who enroll in a MOOC and successfully finish a course to the standards specified by the instructor (Koller, Ng, Do, & Chen, 2013). However, the varying and shifting learners’ intentions for participating in MOOCs calls for new metrics that go above and beyond the traditional benchmarks of certification, grades, and completion in order to understand what actually happens in a MOOC (Bayne & Ross, 2014; Ho et al., 2014). In our attempt to understand persistence in MOOCs that captures these varying motivations, we will employ different data sources such as micro-analytic measures (DiBenedetto & Zimmerman, 2010) and trace log data to examine whether specific self-regulated learning process relates to participants persistence in achieving the individual goals they set for themselves during the first week of the course.

References

Allen, I.E., & Seaman, J. (2011). Sizing the opportunity, the quality and extent of online education in the United States, 2002 and 2003. Babson Survey Research Group. Retrieved from http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/sizing-the-opportunity.pdf

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2011). Going the Distance, Online Education in the United States. Quahog Research Group. Retrieved from http://www.babson.edu/Academics/centers/blank- center/global-research/Documents/going-the-distance.pdf

Anderson, M. (2011). Crowdsourcing higher education: A design proposal for distributed learning. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 7, 576-590.

Bayne, S., & Ross, J. (2014). The pedagogy of the Massive Open Online Course (MOOC): The UK view (Research Report). United Kingdom: The Higher Education Academy. Retrieved from http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/resources/detail/elt/the_pedagogy_of_the_MOOC_UK_view

Couros, A. (2009). Open, connected, social implications for educational design. Campus-Wide Information Systems, 26(3), 232-239.

Cristensen, R., & Knezek, G. (1999). Stages of adoption for technology in education. Computers in NZ Schools, 11, 25-29.

DiBenedetto, M. K., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2010). Differences in self-regulation processes among students studying science: A Microanalytic investigation. The International Journal of Educational and Psychological Assessment, 5.

Ganza, W. J. (2012). The impact of online professional development on online teaching in higher education (Doctoral dissertation, University of North Florida). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/345

Ho, A. D., Reich, J., Nesterko, S., Seaton, D. T., Mullaney, T., Waldo, J., & Chuang, I. (2014). HarvardX and MITx: The rst year of open online courses (HarvardX and MITx Working Paper No. 1). Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=2381263 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2381263

Hung, M., Chou, C., Chen, C., & Own, Z. (2010). Learner readiness for online learning: Scale development and student perceptions. Computers & Education, 55, 1080-1090.

Kilgore, W., & Lowenthal, P. R. (2015). The Human Element MOOC: An experiment in social presence. In R. D. Wright (Ed.), Student-teacher interaction in online learning environments (pp. 373-391). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Koller, D., Ng, D., Do, C., & Chen, Z. (June 3, 2013). Retention and intention in massive open online courses: In depth. Educause Review. Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/retention-and-intention-massive-open-online-courses- depth-0

Kop, R. (2011) The challenges to connectivist learning on open online networks: Learning experiences during a massive open online course. The International Review Of Research In Open And Distance Learning, 12(3).

Macleod, H., Haywood, J., Woodgate, A, & Sinclair, C. (2014) Designing for the unknown learner. EMOOCs 2014 European MOOC Stakeholders Summit, Experience Track 245-248.

Ragan, L.C., Bigatel, P.M., Kennan, S.S.,& Dillon, J.M (2012). From research to practice: Towards the development of an integrated and comprehensive faculty development program. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 16(5), 71-86.