Unit 2: Hades and the Underworld

Before You Read

Discuss the following questions with a classmate.

- What is knowledge?

- How do people learn?

- What is real, and what is fake, and how do you know?

Vocabulary Building

Find the word in the paragraph given. Use the synonyms and definition to help. (Definitions from Merriam-Webster Learner’s Dictionary.)

- P2: not ignorant or narrow in thinking (adj.) ______________________________________________

- P2: to burn very brightly and intensely (v.) _______________________________________________

- P2: a doll that is moved by putting your hand inside it or by pulling strings or wires that are attached to it (n.) (2 options) ____________________________________________________________

- P7: freed (adj.) _________________________________________________________________________

- P7: to force (someone) to do something (v.) ______________________________________________

- P7: unable to understand something clearly or to think clearly: confused (adj.) _____________

- P8: a place that provides shelter or protection (n.) _______________________________________

- P8: feeling doubt about doing something: not willing to do something (adv.) _______________

- P9: to think deeply or carefully about (something) (v.) ____________________________________

Story: Plato’s Allegory of the Cave

by ancient Greek Philosopher Plato in his book Republic, written around 380 BCE

Introduction from Victor Moeller’s book Introduction to College Philosophy, pg 84:

The son of a wealthy and noble family, Plato (427-347 B.C.) was preparing for a career in politics when the trial and eventual execution of Socrates (399 B.C.) changed the course of his life. He abandoned his political career and turned to philosophy, opening a school on the outskirts of Athens dedicated to the Socratic search for wisdom. Plato’s school, then known as the Academy, was the first university in western history and operated from 387 B.C. until A.D. 529, when it was closed by Justinian.

Unlike his mentor Socrates, Plato was both a writer and a teacher. His writings are in the form of dialogues, with Socrates as the principal speaker. In the Allegory of the Cave, Plato described symbolically the predicament in which mankind finds itself and proposes a way of salvation. The Allegory presents, in brief form, most of Plato’s major philosophical assumptions: his belief that the world revealed by our senses is not the real world but only a poor copy of it, and that the real world can only be apprehended intellectually; his idea that knowledge cannot be transferred from teacher to student, but rather that education consists in directing student’s minds toward what is real and important and allowing them to apprehend it for themselves; his faith that the universe ultimately is good; his conviction that enlightened individuals have an obligation to the rest of society, and that a good society must be one in which the truly wise (the Philosopher-King) are the rulers.

The Allegory of the Cave can be found in Book VII of Plato’s best-known work, The Republic, a lengthy dialogue on the nature of justice. Often regarded as a utopian blueprint, The Republic is dedicated to a discussion of the education required of a Philosopher-King.

Translated by Benjamin Jowett in 1871, adapted by Charity Davenport, $\ccbysa$

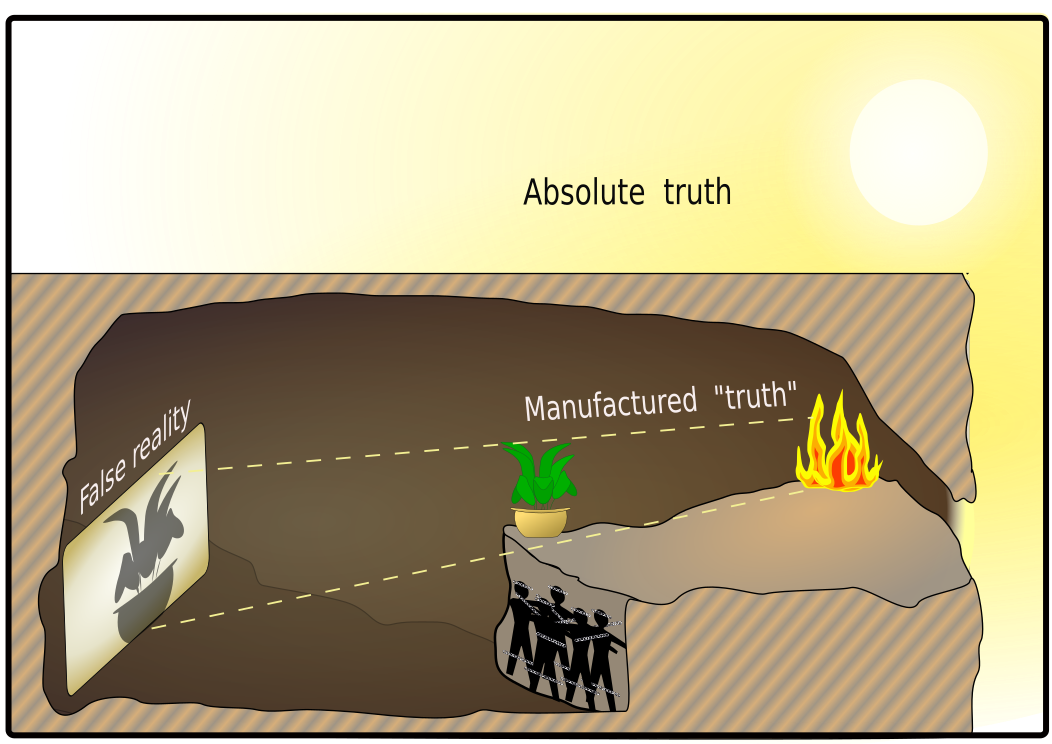

Socrates: And now, I said, let me show in an allegory how far our nature is enlightened or unenlightened: Imagine this–human beings living in a underground cave which has a mouth open towards the light and reaching all along the cave; here they have been from their childhood, and have their legs and necks chained so that they cannot move, and can only see what is in front of them, being prevented by the chains from turning around their heads. Above and behind them a fire is blazing at a distance, and between the fire and the prisoners there is a raised way, and you will see, if you look, a low wall built along the way, like the screen which marionette players have in front of them, over which they show the puppets.

Glaucon: I see.

Socrates: The low wall and the moving figures of which the shadows are seen on the opposite wall of the cave. And do you see, men passing along the wall carrying all sorts of things, and statues and figures of animals made of wood and stone and various materials, which appear over the wall? Some of them are talking, others silent.

Glaucon: You have shown me a strange image, and they are strange prisoners.

Socrates: Not much different from ourselves, and they see only their own shadows, or the shadows of one another, which the fire throws on the opposite wall of the cave?

Glaucon: True, how could they see anything but the shadows if they were never allowed to move their heads?

Socrates: And of the objects which are being carried in like manner they would only see the shadows?

Glaucon: Yes.

Socrates: And if they were able to converse with one another, would they not suppose that they were naming what was actually before them?

Glaucon: Very true.

Socrates: The prisoners would mistake the shadows for reality. And suppose further that the prison had an echo which came from the other side, would they not be sure to think when one of the passers-by spoke that the voice which they heard came from the passing shadow?

Glaucus: No question.

Socrates: To them, I say, the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images.

Glaucon: That is certain.

Socrates:And now look again, and see what will naturally follow if the prisoners are released and enlightened of their error. At first, when any of them is liberated and compelled suddenly to stand up and turn his neck round and walk and look towards the light, he will suffer sharp pains; the glare will distress him, and he will be unable to see the realities of which in his former state he had seen the shadows; and then imagine someone saying to him that what he saw before was an illusion, but that now, when he is approaching nearer the outside of the cave, and his eye is turned towards more real existence, he has a clearer vision,—what will be his reply? And when released, they would still persist in maintaining the superior truth of the shadows. And you may further imagine that his instructor is pointing to the objects as they pass and requiring him to name them,—will he not be perplexed? Will he not think that the shadows which he formerly saw are truer than the objects which are now shown to him?

Glaucon: Far truer.

Socrates: And if he is compelled to look straight at the light, will he not have a pain in his eyes which will make him turn away to take refuge in the objects of vision which he can see, and which he will conceive to be in reality clearer than the things which are now being shown to him?

Glaucon: True.

Socrates: When dragged upwards, they would be dazzled by excess of light. And suppose once more, that he is reluctantly dragged up a steep and rugged ascent, and held fast until he is forced into the presence of the sun itself, is he not likely to be pained and irritated? When he approaches the light his eyes will be dazzled, and he will not be able to see anything at all of what are now called realities.

Glaucon: Not all in a moment.

Socrates: He will need to grow accustomed to the sight of the upper world. And first he will see the shadows best, next the reflections of men and other objects in the water, and then the objects themselves; then he will gaze upon the light of the moon and the stars and the twinkling heaven; and he will see the sky and the stars by night better than the sun or the light of the sun by day?

Glaucon: Certainly.

Socrates: Last of all he will be able to see the sun, and not mere reflections of him in the water, but he will see him in his own proper place, and not in another; and he will contemplate him as he is.

Glaucon: Certainly.

Socrates: He will then proceed to argue that this is the Sun that gives the season and the years, and is the guardian of all that is in the visible world, and is the reason all things which he and his fellows have experienced are shadows?

Glaucon: Clearly, he would first see the sun and then reason about it.

Socrates: They would then pity their old companions left in the cave. And when he remembered his old prison, and what is known of the cave and his fellow-prisoners, do you not suppose that he would feel fortunate that he has changed and pity them?

Glaucon: Certainly.

Socrates: And if there were a contest, and he had to compete in measuring the shadows with the prisoners who had never left the cave, while his sight was still weak, and before his eyes had become steady (and the time which would be needed to acquire this new habit of sight might be very considerable), would anyone of them believe him? Men would say of him that up he went and down he came back without his eyes; and that it was better not even to think of leaving; and if any one tried to free another and lead him up to the light, let them only catch the offender, and they would put him to death.

Glaucon: No question.

Socrates: The prison is the world of sight, the light of the fire is the sun. This entire allegory, I said, you may now apply, dear Glaucon, to the previous argument; the prison-house is the world of sight, the light of the fire is the sun, and you will not misunderstand me if you interpret the journey upwards to be the ascent of the soul into the intellectual world according to my poor belief which I have expressed—whether rightly or wrongly God only knows. But, whether true or false, my opinion is that in the world of knowledge the idea of good appears last of all, and is seen only with an effort; and, when seen is also inferred to be the universal author of all things beautiful and right, parent of light in this visible world, and the immediate source of reason and truth in the intellectual; and that this is the power upon which he who would act rationally either in public or private life must have his eye fixed.

Glaucon: I agree, as far as I am able to understand you.

Socrates: But then, if I am right, certain professors of education must be wrong when they say that they can put knowledge into the soul which was not there before, like sight into blind eyes.

Glaucon: They absolutely say this.

Socrates: Our argument shows that the power and capacity of learning exists in the soul already; and that just as the eye was unable to turn from darkness to light without the whole body, so too the instrument of knowledge can only by the movement of the whole soul be turned from the world of becoming into that of being, and learn by degrees to endure the sight of being, and of the brightest and best of being, or in other words, of knowledge.

Glaucon: Very true.

Socrates: And must there not be some way which will effect conversion in the easiest and quickest manner; not implanting the capacity of sight, for that exists already, but has been turned in the wrong direction, and is looking away from the truth?

Glaucon: Yes, he said, such a way must be assumed.

CEFR Level: B1

Comprehension Questions

Answer the questions below according to the reading using your own words. Make a note of where you found the answer in your reading.

- Describe the situation of the prisoners in the cave.

- Why can the prisoners only see what is in front of them?

- How do the prisoners respond to being chained?

- What happened to the prisoners as people carried tall statues across the fire-lit curtains?

- How does the sunlight affect the prisoners’ eyes after being exposed to the darkness for a long time?

- What are the two causes of blindness mentioned in the allegory?

- When the prisoner returned to the cave to tell others what he had seen and heard, what was the others’ attitude?

- What does the sun represent?

- What does Socrates say is the way that teachers should teach?

Critical Thinking Questions

Answer the following questions. Compare your answers with a partner.

- Summarize Plato’s analysis of his allegory. (You may need this for your writing assignment.)

- What can be implied about the process of getting accustomed to the light?

- Do you agree that being in a prison for a long time will affect the prisoners’ behavior, so they will be more likely to act strangely? Explain why or why not.

- Why do the other prisoners consider the first prisoner to have been ruined by venturing outside?

- Compare the feelings of prisoners before and after being in prison.

- Do you agree with Plato’s idea of education? Are you responsible for your own learning? What are three things you can do to be a better learner?

Vocabulary from the Stories

There are no exact words that come from this story, but there are a lot of interesting words and phrase related to the story. Answer the questions below and discuss your answers with a classmate.

- Educate: According to the Oxford Dictionary, the word educate comes from Origin Late Middle English from the “Latin educat- ‘led out’, from the verb educare, related to educere ‘lead out’.” How might the origin of this word be related to Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave”?

- What does the phrase “ignorance is bliss” mean, and how is it related to the story?

- What does the phrase “fear of the unknown” mean, and how does it relate to the story?

- What does the idiom “living under a rock” mean, and how is it related to the story?

- What does the phrase “the truth hurts” mean, and how does it relate to the story?

- What does the idiom “see the light” mean, and how is it related to the story?

- What does the idiom “the light at the end of the tunnel” mean, and how does it relate to the story?