Unit 3: Adventure and The Hero’s Journey

Theseus and the Minotaur

adapted from Favorite Greek Myths by Lilian Stoughton Hyde, $\ccpd$

Theseus and his mother Aethra lived at the bottom of a great mountain, at a place called Troezen. One day, long before the earliest time that Theseus could remember, Aegeus, the father of Theseus, took Aethra out in the forest near the mountain side. There he lifted a huge rock and buried underneath it his sword and sandals. Then rolling the rock back into its place, he told Aethra that when Theseus was strong enough to lift this rock, she might let him take the sword and sandals and go to his father in Athens. This was the last that Aethra had ever seen of Aegeus, but she knew that he was the king of Attica and sat on the throne in the beautiful city of Athens.

At last the time came when Theseus had reached a man’s full strength and could lift the great rock. Then taking the sword and the sandals from under it, he secured the sword at his side, put the sandals on his feet, and was soon ready to set out for Athens.

At that time the country between Troezen and Athens was wild and rocky, and behind many of the rocks lurked giants and robbers, ready to jump out and attack lonely travelers; but by sea, the way was much safer. Aethra’s father, who was getting old and weak, thought that Theseus had better go by sea, but Theseus said, ” No! Do I not hold my father’s good sword? I will go by land, and if I meet with any adventures, so much the better.” So Theseus said goodbye to his mother and his grandfather and began his journey by land.

He had not gone far among the wild rocks near Troezen before he was attacked by robbers and giants, but none of them could defeat Theseus and his father’s sword. One giant named Sinis would bend down the tops of two pine trees, tie travelers to the trees, and then let them spring back again, splitting the traveler in two, catapulting them across the land. Not far away lived another robber, Procrustes, who used to pretend to entertain strangers at his hotel of sorts. If they were too tall for his bed, he would cut off their heads or their feet; if they were too short for it, he would stretch them to fit it. Procrustes, too, was killed by Theseus. Afterward, other robbers and giants met the same fate.

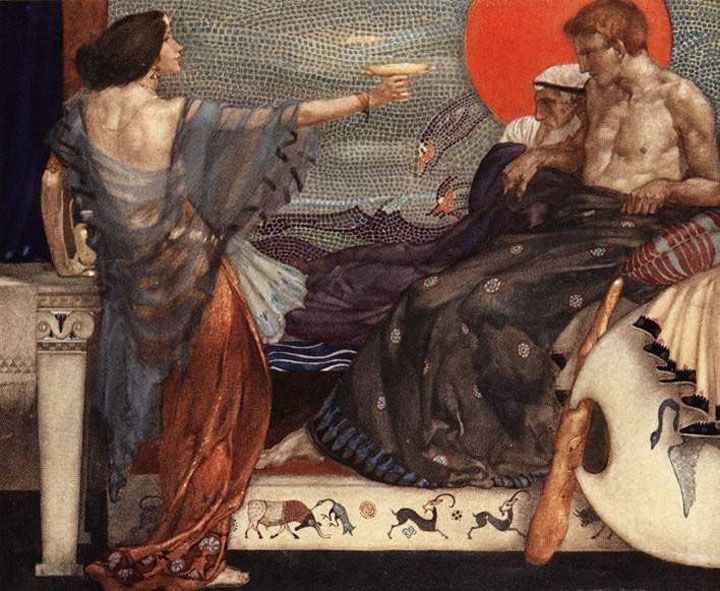

By the time that Theseus reached Athens, he was well known in that city; for the people all along the way had been eager to spread the news of what he had done. In fact, only one man in all Athens knew nothing of his coming, and that man was his own father, Aegeus, the king. At this time Medea, a beautiful woman and a famous sorceress, was living in the king’s palace. As she had a son whom she wished to place on the throne after King Aegeus was gone, perhaps it was natural that she should be sorry to have Theseus come to Athens. But this perfectly natural feeling of Medea’s led to a very evil act. By means of her knowledge of poisonous herbs, she mixed a very potent potion, which would cause instant death to anyone who drank of it. Then, telling King Aegeus that the young stranger was a traitor, and had plotted to murder him, she convinced him to hand this cup to Theseus when he presented himself at the throne. With no thought that it could contain poison, Theseus innocently raised the fatal cup to his lips, intending to drink to the king. Just then Aegeus noticed the sword Theseus carried, and he knew by the carving on its ivory hilt that the so-called traitor was his own son. Instantly, he struck the cup from the hand of Theseus, and welcomed the young man as a father should welcome his son.

When Medea saw that her evil scheme had failed, and that Theseus was recognized by his father, she was frightened. She did not dare to plan any further mischief to Theseus but used all her magic to get herself safely away. First, she made a thick mist rise from the river. Then, in the sudden darkness and confusion caused by the mist, she called her winged dragons, jumped into her chariot, and was soon far away from Athens, where she never dared to return.

The people lost no time in telling the king all the brave deeds that Theseus had performed on his way from Troezen. The king was so well pleased with what he heard, and so glad to have his son come to Athens, that he announced the city would have three days of public rejoicing and feasting. However, in the middle of all this celebration, a messenger came to tell King Aegeus that the collectors of the tribute had arrived from Crete. A long time before, the oldest son of King Minos of Crete had been murdered in Athens. To avenge the death of the prince, King Minos brought a great army against Athens, and required the Athenians to pay him a tribute every ninth year, of seven young men and seven young women, chosen from among the noble families of Athens.

It was rumored that the children of the tribute, as these young men and women were called, were destined to be the meals of the Minotaur, a bloodthirsty and brutal creature, with the body of a man and the head of a bull, which King Minos kept in a labyrinth near his palace. No one who entered the labyrinth had ever been known to come out again. The cruel tribute had been paid twice already, and now the Athenians must pay it for the third time.

Theseus at once was determined to kill the monstrous Minotaur, and so make an end of the tribute. Although King Aegeus tried to persuade him not to do so, he offered himself, before the lots were drawn, as one of the seven young men. This pleased the Athenians and made Theseus very popular. On the day appointed, the six other young men and the seven young women were chosen at random, and everything was made ready for sailing. When starting out on such a sad voyage, it seemed fitting that the ship which carried the children of the tribute should have black sails. This had been done on the two former occasions when the tribute had been paid. Now that there was some hope of a happy outcome of the voyage, King Aegeus gave Theseus a white sail, which he told him to raise instead of the black one, if he happens to succeed in killing the Minotaur, and leaves out on the homeward voyage, safe and well. The aged king then said his goodbyes, telling Theseus, “From the top of that rock I shall watch every day for your return.” Then the black-sailed ship passed slowly out of the dock. The young people that it carried were very sad, for they never expected to see the sunny shores of Greece again, at least none of them but Theseus. He was as cheerful and as full of courage as when he set out for Athens with his father’s sword hanging at his side.

The Slaying of the Minotaur

When the children of the tribute arrived at Crete, Theseus informed King Minos that he meant to kill the Minotaur. King Minos told the prince that if he could perform this task, he and all his friends might go free and that nothing more should ever be said about the tribute. The truth is, this horrible Minotaur was not at all a pleasant pet to keep, for there was always the possibility that he might get out of the labyrinth and do never-ending damage. Therefore, King Minos would really have been very glad to get rid of the Minotaur. Nevertheless, he was so hard-hearted that he would not permit Theseus to go armed to meet the monster; hence there was very little hope of the hero’s success.

That night the young Athenians were thrown into a dungeon under the palace of King Minos, one of them being destined for the Minotaur’s breakfast in the morning. Directly over this dungeon were the rooms of the two daughters of King Minos, Ariadne and Phaedra. As the two sisters stood on the wall, enjoying the moonlight, they heard the complaining of the prisoners. “What a pity it is,” said Ariadne, “that these youths will become food for the Minotaur. I pity young Prince Theseus most of all, because he is so brave. If you are willing, we should help him to slay the Minotaur.” Phaedra was as eager as Ariadne to help the young prince. So the two made a plan that they thought might succeed. They waited until all the king’s household were asleep, then tiptoed softly to the dungeon, and opened the door.

Worn out with lethargy and anxiety, all the prisoners but Theseus had fallen asleep. Theseus, however, was wide awake. Ariadne gestured to him to come out. Then she and Phaedra took him to the place where the famous labyrinth stood. Its white marble walls looked very high and strong in the moonlight. The night was very still, except for the sound of the waves crashing on the shore, and Theseus could clearly hear the heavy breathing of the sleeping Minotaur. “This is the best time to attack the creature; do not wait until morning,” Ariadne whispered, and Theseus knew that she was right. “The Minotaur’s den is in the very heart of the labyrinth,” Ariadne continued. “The sound of his breathing will show you in what direction you must go. Here is a sword, and here is a clew of yarn, by means of which, after you have killed the monster, you can find your way back.”

With these words, she handed him the sword, and the clew of yarn, of which she kept one end in her own hand, then opened for him a door leading to a secret passage into the labyrinth. Theseus, holding the sword in one hand and the string of yarn in the other, entered the labyrinth. The interior as all cut up into narrow paths, bordered by high walls. So many of these paths ended in a blank wall that Theseus often had to retrace his steps. There never was another labyrinth half so complicated as this one, which was made by the famous Daedalus. It was made as winding and confusing as the Maeander River in Phrygia. Back and forth, in and out, Theseus went; he could hear the heavy breathing more and more clearly and knew that he was getting closer to the center, where the monster he was seeking lived. Meanwhile, Ariadne and Phaedra stood at the gate, Ariadne holding her end of the yarn. They waited a long time—they could not tell how long. The moon set behind the hills and left only the light of the stars. Then they heard a great roar that shook the strong walls of the labyrinth. After this everything was still again. It was hard for Ariadne to wait, now, for she did not know whether Theseus might be lying dead inside, or, if he had not been killed by the Minotaur, might have dropped the yarn in the fight, and so be lost in the maze of paths.

At last, she felt the string of yarn tighten, and in a moment more out Theseus came, saying that he had killed the Minotaur. Fortunately, the boat that had brought Theseus and his companions to Crete was still lying on the shore. This made it possible to escape from King Minos before daylight. The sleeping youths in the dungeon were quickly woken up, the little ship was launched, and all were soon ready to set out for Athens. Before going on board, Theseus asked the daughters of King Minos to come with all of them back to Athens with him. “Your father, the king, will be angry,” said he, “when he knows how you have assisted me. This will be the best way to escape his fury.” Having good reason to fear the cruelty of King Minos, the two princesses accepted this invitation.

On their way to Athens, the young people stopped at the island of Naxos. Here, the young men, exhausted from hard rowing and greatly in need of rest, pulled the boat up on the shore, where the whole company set up a camp on the rocks for the night. Very early the next morning they set sail and started off again, but Ariadne, being fast asleep on a rock, was left behind.

When this poor princess awoke, she could hardly believe that Theseus had really meant to desert her. However, there was the boat dancing on the waves, almost out of sight. She watched it until she could no longer look off on the bright water because of the tears in her eyes, and then she heard strange music, a sound of tambourines and pipes, a lyre, and the clash of cymbals. She turned to look toward the woods behind her, from which the sounds came, and saw a chariot drawn by two panthers. In the chariot sat Bacchus, the god of wine, wearing a spotted deer-skin and a crown of cool ivy-leaves. He was surrounded by a merry, dancing crowd of nymphs and satyrs. When Bacchus heard Ariadne’s story, he said: “Theseus should certainly have taken you to Athens, and considering all you did to help him, he ought, at the very least, to have made you a queen. But never mind, you shall have a better crown than any he could have given you. With these words, the god placed a crown of nine bright stars on Ariadne’s head. After this, he persuaded the other gods to take her up into the sky, among themselves. There, in the northern sky, her crown still shines.

With all his courage Theseus must have been a very forgetful young man, for he not only left Ariadne on the island, but he forgot to raise the white sail on the homeward voyage, as he had promised to do, if all went well. Thus, it happened that the ship came back to Athens with the ominous black sail flying. Poor old King Aegeus, watching from the rock, saw the black sail, and thinking that his son was dead, threw himself into the sea and drowned. The waters in which he threw himself into is now known as the Aegean Sea. So when the children of the tribute arrived safe in the harbor after such a hazardous journey, there was mourning instead of rejoicing. After Theseus was made king, he brought his mother, Aethra, to Athens, and took good care of her for the rest of her life. He ruled wisely and was kind to the poor and the unfortunate.

|

|

Comprehension Questions

Answer the following questions according to the story.

- What kinds of trouble did Theseus meet on his way to Athens?

- What did Procrustes do to travelers he met?

- What did Medea do to try to get rid of Theseus, and why did she want to get rid of him?

- What is the tribute Athenians must pay and why?

- How do they decide who must be given as a sacrifice?

- What color is the sail on the boat that they are on? Why?

- What color sail does King Aegeus give Theseus? Why?

- How does King Minos feel about the Minotaur?

- Who helps Theseus get to the Minotaur and how do they help him?

- What two very forgetful things does Theseus do, and what are the consequences?

Vocabulary and Critical Thinking Questions

Answer the following questions. Compare your answers with a partner.

- Why do you think King Aegeus left his sword and sandals under a heavy rock?

- How would you describe Theseus’ personality?

- We get the word “procrustean” from this story. What does it mean, and in what situations could it be used?

- This story mentions that the Minotaur’s labyrinth is as winding as the Maeander River in Phyrgia (in modern day Turkey). We get the word “meander” in English from this river. Use a dictionary to find the meaning of the word and use it in a sentence.

- We get the word “clue” from this reading, with the original word coming from a clew of yarn. What does “clue” mean, and how does it relate to the story?

- There is an idiom related to this story: “Take the bull by the horns.” Use a dictionary to find out what it means and describe a situation where you “took the bull by the horns.”

- In paragraph 4, what does it mean that “Afterward other robbers and giants met the same fate”?

- In paragraph 15, what does it mean that Ariadne was “fast asleep” on a rock?

CEFR Level: CEF Level B2