Gary Gallant

Author

Gary Gallant

Affiliation

Cape Breton University

Abstract

The international COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, which closed schools and university classes around the world, hastened the necessity to be able to offer online learning opportunities for students. Many universities already have online course offerings. High Schools have also begun to embrace e-learning, offering a selection of courses online (see Nova Scotia Virtual Schools (NSVS…, n.d.)). The pressing need, however, was to convert existing face-to-face, bricks-and-mortar courses to a fully online environment. It is accepted that an effective e-learning environment will combine elements of behaviourist, cognitivist and constructivist learning theories. It is also accepted that each of these learning theories is enhanced using cooperative learning approaches, be they synchronous or asynchronous. Many educators already offer hybrid courses containing both offline and online components, often including collaborative elements. For the purposes of this writing, the focus will be on online collaborative learning tools, such as Moodle or Google Apps for Education (GAfE). These can be used either to enhance a hybrid learning environment or, in the context of the current international crisis, to offer courses fully online.

Keywords

online learning, learning theory, online collaborative learning, community of inquiry, google apps for education, g suite

Overview

Collaborative Learning Approaches and the Integration of Collaborative Learning Tools (09:48)

Collaborative Learning Approaches and the Integration of Collaborative Learning Tools (09:48)

Introduction

Teaching in the public school system in Nova Scotia, Canada, is likely similar to teaching in most school systems in North America: Teachers are provided with a curriculum document complete with outcomes which must be taught within a particular timeframe – often within a semester or within an academic school year. Some courses have prescribed textbooks and other assigned resources. The aim is for units and lessons to be designed such that they will cover the prescribed outcomes and also be engaging and memorable learning opportunities for students. As with any human undertaking, some teachers are better instructional designers and more effective at implementation than others. It must be acknowledged that there are myriad individual, cultural and other social considerations that are known to affect student learning, which will not be addressed in this writing. That said, there is a base of educational theory and knowledge which should make up the underpinnings of any effective instructional design, whether that instruction be off- or online. Thus, prior to addressing collaborative approaches in online education, we will first briefly examine the role of three traditional educational theories – behavioural, cognitive and constructivist theory – in online learning environments.

Literature Review

Brief Overview of Educational Theory in Online Learning

In A Blended Learning Approach to Course Design and Implementation, Hoic-Bozic, Mornar, and Boticki (2009) state that “High-quality learning environments in general, and especially high-quality online learning environments, should be based on multiple theories of learning” (p.21). Three such theories are addressed below:

Behavioural Theory

Behavioural Theory receives, perhaps, the least print related to online learning. However, Hoic-Bozic et al. (2009) state that, even online, “Students require approval and support, which should be provided as soon as possible” (p.20). In A design framework for online learning environments, Sanjaya Mishra (2002) also suggests the “use of embedded self-assessment questions as interactive activities in the learning materials” (p.495) as one example of an online approach to incorporating behavioural theory.

Cognitivism Theory

Cognitivism theory, as described by Linda Harasim in her book Learning Theory and Online Technologies, contends that “learning is easier if new subject matter is compared to existing knowledge and is structured or representational” (2017, p.51). People will often use the analogy of the mind as a computer, processing information, to describe this theory. It certainly makes sense that one would activate prior knowledge and at times remediate pre-requisite skills in order to progress toward achievement of the learning objective. Any online learning design would also need to achieve this.

Constructivist Theory

Constructivist theory is “the most widely accepted model of learning in education today” (Hoic-Bozic et al., 2009, p.21). Fernando and Malikar support this notion in their work Constructivist Teaching/Learning Theory and Participatory Teaching Methods (2017), which states that it “advocates a participatory approach in which students actively participate in the learning process…knowledge is not passively received but actively built up” (p.110). Heather Smith, in Using Instructional Design to Implement Constructivist E-Learning, states:

Course developers can use the principles of instructional design to systematically and consciously embed constructivist learning projects in a web-based course. Activities like discussion forums, WebQuests, and jigsaw grouping all foster the student-teacher and student-student relationships that engage learners in an online environment. (Smith, 2017)

Notice that many of the proposed constructivist activities are collaborative in nature. In fact, a collaborative approach can be used to enhance activities related to each of the above learning theories.

What are Collaborative Learning Approaches?

Most often, discussions about collaborative learning and its advantages in both off- and online environments begin with the idea that knowledge building is somehow achieved through interaction with others. This idea is often attributed to Russian Psychologist Lev Vygotsky’s who stated many years ago in his book Thought and Language (originally published in 1934) that “Learners are moved forward through stages of cognitive development through socially mediated situations” (as cited in Hirtle, 1996).

In their article Collaborative Learning: A Sourcebook for Higher Education, Smith and MacGregor reflect on this idea stating:

Collaborative learning produces intellectual synergy of many minds coming to bear on a problem, and the social stimulation of mutual engagement in a common endeavor. This mutual exploration, meaning-making, and feedback often leads to better understanding on the part of students, and to the creation of new understandings for all of us. (Smith & MacGregor, 1992)

There seems to be a substantial body of research and evidence available to support these claims which suggests that collaborative learning is an essential component to quality learning, some which will be addressed shortly. In light of this evidence, however, it becomes pivotally important that collaborative learning approaches be applied to the design of any computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) environments.

Two particular collaborative learning approaches I wish to explore further are Linda Harasim’s work on Online Collaborative Learning (OCL) and Garrison, Anderson and Archer’s work on the Community of Inquiry (CoI) model.

Online Collaborative Learning

In describing OCL, Harasim says in her book Learning Theory and Online Technologies (2017):

OCL theory provides a model of learning in which students are encouraged and supported to work together to create knowledge: to invent, to explore ways to innovate, and, by so doing, to seek the conceptual knowledge needed to solve problems rather than recite what they think is the right answer. (as cited in Bates, 2019, p.170)

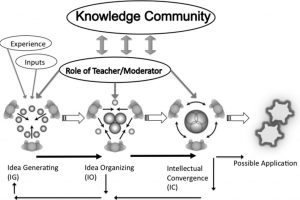

Figure 1: Linda Harasim’s Online Collaborative Learning Model: Pedagogy of Group Discussion (2017) (Image source : https://opentextbc.ca/teachinginadigitalage/wp-content/uploads/sites/29/2014/11/Harasim-Figure-6.3.jpg)

Harasim presents three key phases for constructing knowledge in OCL: idea generating, idea organizing, and intellectual convergence (see Appendix, Figure A). Online learners need to be able to brainstorm ideas, analyse and discuss them and reach a level of intellectual synthesis, understanding and consensus usually through some joint piece of work or assignment (as cited in Bates, 2019, p.170).

paper, that will allow learners to interact in this way. However, as Tony Bates emphasises in his book Teaching in a Digital Age – Second Edition (2019), the teacher’s role is still vital to the success of online collaborative learning “not only in facilitating the process and providing appropriate resources and learner activities that encourage this kind of learning, but also, as a representative of a knowledge community or subject domain, in ensuring that the core concepts, practices, standards and principles [are] integrated” (p.171).

Community of Inquiry

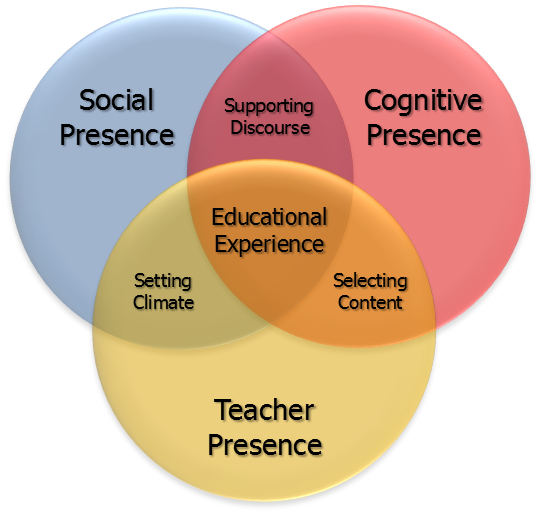

A Community of Inquiry (CoI) is “a group of individuals who collaboratively engage in purposeful critical discourse and reflection to construct personal meaning and confirm mutual understanding” (Bates, 2019, p.172). The CoI model, as described by Garrison, Anderson and Archer in Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education (1999), contends that “learning occurs within the Community through the interaction of three core elements … cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence” (p.3). In her article Designing a Community of Inquiry in Online Courses, Holly Fiock (2020) presents a comprehensive table of instructional activities (p.141) for online instructors which can be implemented to support learning in the CoI model.

Figure 2: Garrison, Anderson and Archer’s Community of Inquiry Model: Communication Medium (1999)

Generally speaking, strategies for incorporating cognitive presence in course design might include having students self-select topics and share resources within the topic being taught and facilitating critical analysis discussions (Fiock, 2020, p.139). Social presence can be established not only by creating collaborative projects, problem solving tasks and small group discussions but also by establishing group cohesion early on through open communication, personal profiles, photos, welcome messages, student profiles, limiting class size, structured learning activities, and activities in which students can incorporate feelings and personal experiences (p.139). With respect to teaching presence, teachers can establish this by providing scaffolding on how the course structure helps the learners, creating mini lectures, embedding personal insight in course material, facilitating discourse, reviewing student comments and moving discussions forward, checking for accurate student understanding and giving detailed feedback to the learner as the content expert (p.140). Generally, with all three core elements, the teacher plays a key role by setting climate, selecting content and supporting discourse (see Appendix, Figure B).

While there are many similarities with both the OCL and CoI models, the most important take away is that both models establish the importance of using collaborative learning approaches in education, with emphasis on their particular application in online education.

Applications

How can Technology be Used to Support Collaborative Learning Approaches?

There is research that indicates, with respect to development of higher-order thinking skills, that online environments are as powerful as, or more so, than campus-based classes (Resta & Laferrièrre, 2007, p.70). The collaborative nature of these environments would certainly have impact. The ability for online platforms to facilitate both synchronous and asynchronous communication would be a benefit related to this.

it has been argued that asynchronous communication allows for more time to reflect on a contribution and refine it than synchronous communication…[However] Synchronous communication tools such as web‐videoconferencing allow for more direct social interaction and feedback among learners and teachers, which may leave less time for reflection, but do allow for direct correction of misconceptions, and may lead to higher levels of learner engagement. (Giesbers et al., 2014)

It should be noted that, even in online environments that are entirely asynchronous, a strong teacher presence, as indicated in the CoI model, can ensure a positive collaborative learning experience for students. There are many online platforms or tools that can be used to effectively implement an online collaborative learning approach.

Online Collaborative Learning Tools

Popular online learning platforms include but are certainly not limited to Moodle, Edmodo, Canvas, and Google Apps for Education. Moodle is used for many online courses at universities and also in many grade school hybrid classrooms in Nova Scotia, Canada, and around the world. Likely, each platform has its own merits. However, for the purposes of this writing, the focus will be on a platform widely available to students and teachers globally that can be used to deliver courses online – that is, Google Apps for Education, or GAfE (Google for Education, n.d.).

What is GAfE?

Google Apps for Education (GAfE), sometimes referred to as G Suite for Education, is an integrated, cloud-based communication, collaboration and creation tool. All created content can be easily shared with others. Because it is cloud-based, students and teachers can collaborate synchronously and asynchronously from any internet device. With the prevalence of portable technologies in society, such as smart phones, tablets or laptops, this becomes a convenient and cost-effective manner for many school districts to implement a powerful online collaborative learning tool.

GAfE in Support of Collaborative Learning Approaches

With a single login, students and teachers have access to a large number of Google applications including the following:

Google Classroom

Google Classroom generally acts as the main organizational platform and primary communicative point of contact with students. It is in this space where a teacher could post short lecture videos or other course content for students to view and review asynchronously at their own convenience and pace, increasing cognitive presence, in support of the CoI model. They can also create and post collaborative activities, communicate with students, creating social presence, in support of the CoI model. A teacher could also gather information via surveys and questionnaires using Google Forms. Also, assignments can be created and posted in Google Classroom with the ability to give descriptive feedback directly on the submitted work, including a grade, creating teacher presence, again in support of the CoI model. The collaborative aspects of Google Classroom are also, clearly, in line with the OCL model as well.

Google provides a tutorial video to show how to set up Google Classroom and use it to set up classes, create and organize content and give feedback on assignments.

Classroom 101 (01:50)

Classroom 101 (01:50)

Google Docs, Sheets, Slides

These applications allow students and teachers to collaborate synchronously and asynchronously on documents, spreadsheets, and presentations. This supports Harasim’s OCL model by creating opportunity for idea generating and organizing, along with the synthesis of a product or consensus understanding.

Google Sites

Google sites is an easy-to-use web-building tool that allows enables teachers to create websites, perhaps for hosting course curriculum. It is also a creative platform that would allow students to collaborate to create, organize and present content, in support of both OCL and CoI models.

Google Groups

Google Groups can be created and used to allow for organized, threaded discussions exploring and expanding upon course content, promoting communication, conversation and collaboration resulting in deeper understanding, in support of both OCL and CoI models.

Google Hangouts

Using Google Hangouts, students and teachers could have live synchronous sessions where they could collaborate, engage in discussions or conduct debates, creating teacher and social presence in support of the CoI model.

Google Forms

Here a teacher can create forms, quizzes or surveys which can be shared on Google Classroom. Google Forms automatically collects, compiles and analyzes responses. A teacher could post surveys and questionnaires using Google Forms before, during and/or after activities to gather formative information and promote deeper interaction with course material, promoting cognitive and teacher presence, in support of the CoI model.

Gmail

With GAfE, secure email accounts can be created for all students and teachers. This is yet another collaboration tool for teachers and students, enabling secure communication from any online device, in support of both OCL and CoI models.

Google Drive

With Google Drive, students and teachers have access to a large storage space where they can organize assignments, documents, or class curriculum securely and access them from any device. All content stored here is easily shareable as well, in support of both OCL and CoI models.

Google Jamboard

Google Jamboard acts as an interactive smartboard, where teacher and/or groups of students can collaborate on a virtual whiteboard to create sketches or brainstorm ideas, again, in support of both OCL and CoI models.

Privacy, Copyright and Digital Accessibility & Access Privacy

Google’s policies and procedures related to Privacy & Terms can be viewed at https://policies.google.com/privacy.

While privacy settings can be adjusted within particular products, they can also be manages using the Google Product Policy Guide (available at https://policies.google.com/technologies/product-privacy).

More privacy information related specifically to G Suite for Education, which includes the ability to choose a region where data is stored, can be found at https://support.google.com/a/topic/7558840?hl=en&ref_topic=7556782

Copyright

Instructional designers and practitioners must continue to obey copyright laws when using and posting instructional materials. Materials related to Copyright Law and Fair Dealings Guidelines can be downloaded from the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC) Web site: www.cmec.ca/copyrightinfo.

Digital Accessibility & Access

Google has many products and features for designers and users to support digital accessibility. More information is available at https://www.google.ca/accessibility/.

There may be issues with access to particular applications in some jurisdictions, depending on decisions made by system managers. For example, Google Hangouts – a video teleconferencing application – is currently disabled for students in the Conseil Scolaire Acadien Provincial (CSAP), in Nova Scotia, Canada.

Conclusions

As educators across the country and around the world hasten to develop online course structures, it is important to note that effective design of online learning is firmly grounded in traditional behaviourist, cognitivist and constructivist learning theories. Collaborative learning approaches such as Harasim’s Online Collaborative Learning model and Garrison, Anderson and Archer’s Community of Inquiry model have been demonstrated to be advantageous for students’ cognitive development. There are many online platforms, including Google Apps for Education, which can be used to build courses that support these OCL and CoI models. Within Google Apps for Education and with Google Classroom, the creative potential for an instructional designer to build an effective, engaging and collaborative online course is quite limitless. This GAfE product is an extensive, cost-effective and easily accessible collaborative learning tool for any educator interested in transitioning to an online learning environment.

References

Bates, A.W. (2019). Teaching in a Digital Age – Second Edition. Vancouver, B.C.: Tony Bates Associates Ltd. Retrieved from https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/teachinginadigitalagev2/

Fernando, S., & Marikar, F. (2017). Constructivist Teaching/Learning Theory and Participatory Teaching Methods. 110-122. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5430/jct.v6n1p110

Fiock, H. (2020). Designing a Community of Inquiry in Online Courses. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 21(1), 134-152. doi: https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v20i5.3985

Garrison, D., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999). Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. Retrieved from https://auspace.athabascau.ca/bitstream/handle/2149/739/?sequence=1

Giesbers, B., Rienties, B., Tempelaar, D. & Gijselaers, W. (2014). A dynamic analysis of the interplay between asynchronous and synchronous communication in online learning: The impact of motivation. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 30(1), 30-50.

Google for Education. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://edu.google.com/

Google for Education (2019, January 8). Classroom 101. [YouTube video]. Available from https://youtu.be/DeOVe2YV2Io

Harasim, L. M. (2017). Learning theory and online technologies (Second ed.). New York: Routledge

Hirtle, J. S. P. (1996). Coming to Terms: Social Constructivism. The English Journal, 85(1), 91-92. doi: 10.2307/821136

Hoic-Bozic, N., Mornar, V. & Boticki, I. (February 2009). A Blended Learning Approach to Course Design and Implementation [PDF File]. Transactions on Education 52(1), Retrieved from https://esanderslearningtheories.weebly.com/uploads/2/5/6/4/25641196/hoic-bozic___blended_learning_approach_to_course_design_and_implementation.pdf

Mishra, S. (2002). A design framework for online learning environments. British Journal of Educational Technology, 33(4), 493-496. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ezproxy.cbu.ca/doi/pdf/10.1111/1467-8535.00285

NSVS Launchpad. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://nsvs.ednet.ns.ca/launchpad/launchpad37/mod/page/view.php?id=11251

Resta, P., & Laferrière, T. (2007). Technology in Support of Collaborative Learning. Educational Psychology Review, 19(1), 65–83. doi: 10.1007/s10648-007-9042-7

Smith, B.L., MacGregor J. (1992). Collaborative Learning: A Sourcebook for Higher Education. University Park, PA: National Center on Postsecondary Teaching, Learning and Assessment (NCTLA). 9-22. Retrieved from https://www.evergreen.edu/sites/default/files/facultydevelopment/docs/WhatisCollaborativeLearning.pdf

Smith, H. (2017). Using Instructional Design to Implement Constructivist E-Learning. In Desmarais P., & Fuller, M. (Eds.), Learning Theory and Educational Technology. Idaho: Boise State University. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/a/boisestate.edu/edtech504/

Tomar, D. (2018, January 31). Synchronous Learning vs. Asynchronous Learning in Online Education. Retrieved from https://thebestschools.org/magazine/synchronous-vs-asynchronous-education/