Trudy McCarthy

Author

Trudy A. McCarthy

Affiliation

Memorial University of Newfoundland in association with Cape Breton University / Graduate Student

Abstract

This document addresses the need for Canadian K-12 educators to take a step back and ensure they are referencing both a model of ID and learning theory as they navigate a rapid transition to online learning during the 2020 COVID – 19 crises. Although the first instinct of many educators is to provide curricular based assignments and assessments as quickly as possible, it is not the best course of action under the immense pressures of social distancing and a transition, without warning, to online learning. Therefore, it is within a teacher’s best interest to use ID, in a modified form, to guide their choices in creating a safe and caring learning environment online for their students. Thus, the purpose of this document is to familiarize educators with the Dick and Carey model of ID and encourage its use, from a Constructionist learning perspective, to utilize gamification as a strategy for the rapid implementation of global K-12 online learning, to ease the pressures of the COVID – 19 crises.

Keywords

Instructional Design, Dick and Carey Model, Constructivist, Constructionist, Learning Theory, K-12, Online Instruction, Technology, Gamification, COVID – 19

Overview

Canadian K-12 Educators: A rapid transition to online learning during COVID -19 (03:07)

Canadian K-12 Educators: A rapid transition to online learning during COVID -19 (03:07)

Introduction

As 2020 enters the end of its third month, the world is confronting a reality never faced by modern society; a pandemic, COVID – 19, that is uncontrollable, even with modern medicine. Daily, countries are closing their borders, and people are dying by the hundreds, communities are distancing themselves and imposing mandatory quarantines using non-compliance laws, as businesses close with only essential services remaining open. Also, to further the efforts of social distancing, the Canadian K-12 education system has decided to close and mandate, within two weeks, a rapid transition to online learning, which has become a tremendous undertaking in the creation of Instructional Design (ID).

When facing a limited time frame, like the current Canadian K-12 education system is, educators need to take pause and reference both a model of ID and learning theory as they navigate a rapid transition to online learning. Even though there is not enough time to follow the steps required by ID models, their principals, combined with learning theory, can inform design choices and align online instruction with teacher philosophies. Therefore, the focus of this document will be to familiarize educators with the Dick and Carey model of ID and encourage its use, from a Constructionist learning perspective, to utilize gamification as a strategy for the rapid implementation of global K-12 online learning.

Literature Review

According to Snow (2020), the creation and implementation of ID, under ‘normal’ circumstances, is a lengthy process consisting of many participants working together through multiple stages of development (What ID is Not). Nevertheless, the rapid shift to online learning, caused by COVID – 19, that Canadian K-12 Educators are currently facing, is far from ‘normal.’ However, as stated by Patricia, Slagter, McDonald, and Hirumi, (2018) “an instructional design (ID) model, in its most rudimentary form, is a tool for designers to logically engage in producing solutions to instructional problems (p.126).” Thus, ID models, such as the Dick and Carey Model, are still useful tools for assisting K-12 educators in their efforts to create online content for their students. In addition to the use of ID, it is prudent for educators to use the principals of learning theory, for example, Constructionist Learning Theory, to inform the creation of online content, like gamification of curricular outcomes.

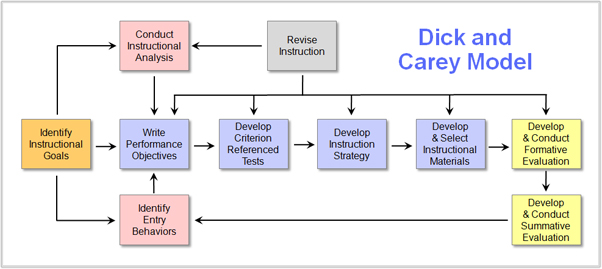

Dick and Carey Instructional Design

According to Kurt (2017), “the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT) defines instructional design as the theory and practice of design, development, utilization, management, and evaluation of processes and resources for learning (para.1).” In keeping with its definition, Patricia, Slagter, McDonald, and Hirumi (2018) assert there are numerous ID models available for educator’s use, aimed towards various modes of instruction (p.126). However, to keep suggestions simple during a time of uncertainty, this document will focus primarily on the Dick and Carey Model of ID (Figure 1) for inspiration and guidance in creating K-12 online learning content.

Figure 1: The Dick and Carey Model of Instructional Design

Even though, in the words of Obizoba (2015), the Dick and Carey Model of Instructional Design uses a comprehensive nine-step system and procedural process to provide strategies for creating course instructions (p. 41)”, it is possible for teachers to condense the steps as a reference in times of crisis, such as COVID – 19. Obizoba (2015), states that the nine steps of the Dick and Carey Model are to:

- identify instructional goals

- conduct instructional analysis

- identify entry-level behaviors

- write performance objectives

- develop criterion-referenced test items

- develop instructional strategy

- develop and select instructional materials

- design and conduct formative evaluation

- revise instruction (p.42)

When perusing an optimal outcome for ID in online learning, educators are advised not to condense or skip steps in the completion of Dick and Cary’s Model. However, it becomes unavoidable during events like COVID – 19, which have forced Canada’s K-12 educational system online without notice.

Skipping specific areas of the Dick and Carey model, for K-12 educators, like conduct instructional analysis and identity entry-level behaviours, would go unnoticed according to Patricia, Slagter, McDonald, and Hirumi, (2018) because:

Teachers do not systematically analyze learner characteristics, let alone stakeholders such as administrators, other educators, or families. This is not to say K-12 teachers do not generate insights about their students’ (or others’) needs, just that they do so in ways very different from the procedures suggested by most ID models (p.126).

Besides, K-12 curricular outcomes cover much of the groundwork for ID, which covers the instructional goals section when amended to include the use of online learning technologies. As for the completion of goals 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9, teachers, in such a rapid transition to online learning, would use them as a checklist to inform the creation of a basic, yet, interactive and fluid learning system for their students, which aligns with the model because of its fluidity.

The connection between constructivist and constructionist learning theory.

Although under pressure, educators still need to ensure their online learning environment embodies a theory of learning. For decades the Canadian educational system has followed the Objectivist Approach to Learning, which simplified by Kraiger (2008), views students as porous, “in a passive role, tasked only with absorbing that information identified through prior analysis (p.456),”or relayed through instruction. Although the Objectivist approached proved successful in producing higher test scores through memorization and summative testing, educators, over the past two decades, have begun to shift towards a student-centred Constructivist Approach to Learning. According to Kraiger (2008), “constructivist learning approaches were developed as a radical departure from objectivist approaches that were built on the notion of an objective world independent of the human mind to be communicated down from instructor to learner (p. 457).”

Presently, an instructor to learner objectivist educational environment is not possible in the newly online-based Canadian K-12 educational system. Luckily, as mentioned in the paragraph above, there has been a shift towards a Constructivist Approach to learning. Mohammad and Rob (2018) define “Constructivism [as] an educational philosophy proposed by Jean Piaget who suggested that knowledge is not simply transmitted from teacher to student, but actively constructed by the mind of the learner (p.274).” The notion that students actively construct their knowledge fits within the framework of online education because students are separated from their teachers and expected to have the autonomy to regulate their learning. Mohammad and Rob (2018) also detailed the evolution of the Constructivist Theory of Learning into a theory which embraces an elemental curiosity existing among 21st Century students, called Constructionism:

Constructionism is a learning theory initiated by Seymour Papert of the MIT Media Lab, who advocated that learning is most effective when the learner designs or constructs a tangible or meaningful product as part of an educational activity (Papert, 1980). Papert’s Constructionism is inspired by the constructivist perspective of learning proposed by Jean Piaget. However, Constructionism asserts that it is not only the constructing process of something that learning becomes truly meaningful for the learner, but that the creation process and the end product must be shared with others to get the full benefit of learning (p. 274).

In addition to Mohammad and Rob’s definition, Parmaxi and Zaphiris (2015) claim, “Constructionism assumes that knowledge is better gained when students find this knowledge for themselves when engaging in the making of concrete and public artifacts (p.33).” Therefore, K-12 educators, when using the principals of Constructionism to design online learning environments, are utilizing student’s natural inquisitiveness to construct their knowledge, and, according to researchers, gamification is an excellent way of doing so successfully. Especially during the COVID – 19 school closures and the hastened time frame for teachers to create online learning for their students.

Constructionist learning theory used in gamification redefined in creation.

According to An (2016), computer games are culturally significant as an influential factor to the motivation in the lives of the 21st Century learner. Upon realizing the motivational potential of gaming, Educators have been, for several decades, implementing the strategy of gamification into the classroom (p. 556). Gamification (n.d.), according to the Merriam Webster online dictionary is defined as “the process of adding games or game like elements to something (such as a task) so as to encourage participation (para. 1),” and with participation being key to the success of ID, it stands to reason, gamification would be an asset in ID for online learning. Kafai and Burke (2015) argued that educators who use gamification in their ID, are part of two leagues of thought, those who promote commercial gaming like Mind Craft, and those who focus on simple educational games like Dragon Box Algebra (p.313). They also “pointed out that while the first group embraces games and abandons school, this second group often embraces school to the detriment of anything that looks like real gaming (p.14).” Thus, meaning gamification within either group would be a hindrance for the use in the rapid creation of ID for online learning, like what is currently required by the Canadian education system. However, by redefining gamification through the theory of Constructionism, it once again becomes invaluable to the rapid creation of ID for K-12 online learning.

In addition to the rise of Constructionism, the K-12 educational system has also begun teaching the mastery of 21st Century competencies. The 21st Century competencies included in education are coding using modern-day technologies, and Constructionism, as stated by An (2016), “suggests that students learn best when they are actively engaged in the construction of concrete and meaningful [products] that can be shared with others. Therefore, technology becomes a medium for intellectual expression and exploration rather than a means of content delivery (p. 556).” Thus, by implementing the principals of Constructionism into their ID for online learning, educators will be using technology for more than a delivery system of content, they will be using it to engage students, on multiple levels, in their learning. According to Kafai and Burke (2015), the principals of Constructionism easily translate into video game making. Intern, awarding students the freedom to practice 21st Century skills, like coding and making, while at the same time providing infinite possibilities for the integration of multiple subject curricular outcomes, as well as necessary life skills (p.316), which is useful when engaging in a rapid transition to online learning.

Examples of technology for constructionist game-based K-12 online learning

This section intends to provide technological resources as a starting point for educators in their ID for online Learning to act as catalysts for student creativity. According to Parmaxi and Zaphiris (2015):

Over the past years, educators have been using different types of digital media for enhancing new forms of teaching and learning. Amongst these technologies are social media or social technologies that came into view as a major element of the Web 2.0 movement. Prevalent software of this movement is blogs, wikis, podcasting, videoblogs, microblogs, digital artifacts sharing platforms, social networks and social bookmarking tools. (p. 34).

However, with the popularity of coding, students are designing and sharing artifacts of their own. Below are a few examples of free programs teachers can use in an expedient transition to online learning to generate student engagement.

G-Suite

- is used by many school boards as their primary source of communication

- it has several apps for use online: Google Classroom, Flatt, Sites, Blog, Docs, Slides to name a few (Google, 2020)

Scratch

- block coding

- create games, music videos, stories, and animations (Scratch 2020)

Plotagon

- block coding

- video creation, animations (Plotagon 2020)

Conclusions

As the world fights COVID – 19, educators are swiftly mobilizing to provide students with online education and, in doing so, must consider many factors in their ID. Like wheater or not to use the Dick and Carey Model of ID discussed in this document, as well as a learning theory to inform their decision, akin to the Constructionist approach to leaning discussed. However, it is also vital, in such an accelerated transition to online learning, for teachers to consider student digital literacy and technological access as well. Reynolds (2016), assert, “reflecting inequalities stemming from variation in the sophistication of use and user expertise, is the condition of digital literacy (p.737).” He also states that access and frequency of engagement with technology at home is a crucial factor in students’ ability to self-motivate in an online learning environment (p.737). Thus, reiterating the importance of the need for educators to take a step back, during the chaos of deadlines, and assess what is essential in their ID for student success.

In times of crisis and upheaval, students do not need increased levels of stress or expectations and the results of An’s (2016) study “indicate that designing educational computer game[s] offers a rich context for developing many 21st century skills, such as creative thinking, critical thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, and digital media literacy (p.565).” As well as, in the words of Kafai and Burke (2015) “genuinely introduces children to a range of technical skills but also better connects them, addressing the persistent issues of access and diversity present in traditional digital gaming cultures (p.313).” Thus, creating a safe and caring learning environment, through technology, at home for students, during this time of uncertainty.

References

An, Y. (2016). A case study of educational computer game design by middle school students Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/s11423-016-9428-7

Çakirolu, Ü., Yildiz, M., Mazlum, E., Turan Güntepe, E., & Aydin, S. (2017). Exploring collaboration in learning by design via weblogs. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 29(2), 309-330. doi: http://dx.doi.org.qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/10.1007/s12528-017-9139-z

Gamification. (n.d.). In Merriam-Webster dictionary online. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gamification

Google. (2020, March 23). Spark learning with G Suite for Education. G Suite for Education. https://edu.google.com/products/gsuite-for-education/?modal_active=none

Kafai, Y. B., & Burke, Q. (2015). Constructionist gaming: Understanding the benefits of making games for learning Taylor & Francis Ltd. doi:10.1080/00461520.2015.1124022

Kurt, S. (2016, December 12). Dick and Carey Instructional Model, in Educational Technology [Web Page]. Retrieved from https://educationaltechnology.net/dick-and-carey-instructional-model/ (Original work published November 23 2015)

Kurt, S. (2017, March 26). “Instructional Design,” in Educational Technology [Web Page]. Retrieved from https://educationaltechnology.net/instructional-design/ (Original work published December 9 2016)

Kraiger, K. (2008). Transforming Our Models of Learning and Development: Web‐Based Instruction as Enabler of Third‐Generation Instruction. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1(4), 454 – 467. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9434.2008.00086.x

Mohammad, R., & Rob, F. (2018). Dilemma between constructivism and Constructionism. Journal of International Education in Business, 11(2), 273-290. doi: http://dx.doi.org.qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/10.1108/JIEB-01-2018-0002

Obizoba, C. (2015). Instructional design models–framework for innovative teaching and learning methodologies. International Journal of Higher Education Management, 2(1) Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/docview/1844699338?accountid=12378

Parmaxi, A., & Zaphiris, P. (2015). Developing a framework for social technologies in learning via design-based research Routledge. doi:10.1080/09523987.2015.1005424

Patricia J Slagter, v. T., McDonald, J., & Hirumi, A. (2018). Preparing the next generation of instructional designers: A cross-institution faculty collaboration. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 30(1), 125-153. doi: http://dx.doi.org.qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/10.1007/s12528-018-9167-3

Plotagon. (2020, March 23). Animate your message with Plotagon. Plotagon. https://www.plotagon.com/

Reynolds, R. (2016). Defining, designing for, and measuring ‘social constructivist digital literacy’ development in learners: A proposed framework Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/s11423-015-9423-4

Scratch. (2020, March 23). Create stories, games, and animations. Share with others around the world. Scratch. https://scratch.mit.edu/

Simonson, M., simsmich@nsu.nova.edu. (2016). Assumptions and distance education. (cover story) Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com.qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,url,uid&db=eue&AN=116352387&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Snow K. (2020). What ID is Not. The Skills, Attitudes, and Knowledge Needed by IDs [Online] Available at: https://courseware.cbu.ca/moodle [Accessed March 8 2020]