Mark MacFadyen

Author

Mark MacFadyen

Affiliation

Middleton Regional High School

Abstract

Formative feedback is widely regarded as an essential educational practice. High-quality feedback helps students learn, promotes self-regulation and motivation. The Kemp model of Instructional Design is a good match for teachers who value frequent formative feedback and are reflexive in their instruction. New technologies are enhancing the ability of writing teachers to provide high-quality multi-modal feedback and are of particular importance during the worldwide pandemic. Teachers require training to use these technologies effectively and develop pedagogical digital competence. Specific applications discussed include Screencastify (2020, b), Google Workspace for Education applications (Google, n.d., e) and Mote (Mote Technologies, Inc., 2021). Research on each is given, if available, as well as tips for optimizing their use based on the author’s classroom experience.

Keywords

Formative feedback, multi-modal, instructional design, literacy, online teaching, student writing, Screencastify, Mote, Google Workspace

Overview

High-Quality Multi-Modal Formative Feedback (8:54)

High-Quality Multi-Modal Formative Feedback (8:54)

Introduction

High-quality formative feedback is essential for learning, student self-regulation, and motivation. In his review of the literature, Shute (2008) finds formative feedback a fundamental practice in helping students acquire new skills. A range of new technologies now exist that allow students to hear their teacher’s voices, watch videos created specifically for them, and interact synchronously and asynchronously with classmates and instructors. While these innovative technologies have been available for some time, the worldwide pandemic has brought them into focus.

Even with students returning to classes full time this year, absenteeism and periodic attendance in middle school are high. The reasons for this are varied. Students are confined to one classroom all day, are required to wear masks, and unable to participate in regular middle school life. Some parents have chosen to keep their kids home, while for others their mental health and stress level have made regular school attendance difficult. The technologies presented in this paper offer some ways teachers can reach these students in impactful ways. It is important that students still hear the excitement in a teacher’s voice as they talk about their writing, whether they are at their kitchen table or in the classroom. Teachers can now provide multi-modal feedback in timely and highly accessible ways.

Literature Review

Formative Feedback

Formative feedback is well supported in the literature as an essential educational practice (Graham, Hebert & Harris, 2015; Moreno, 2004; Shute, 2008). Like any term, there are multiple definitions found in the literature. Shute (2008) defines it as “information communicated to the learner that is intended to modify his or her thinking or behavior for the purpose of improving learning” (p. 154). Hattie and Timperley (2007), well-respected researchers in the field of formative assessment, give this description: “information provided by an agent (e.g., teacher, peer, book, parent, experience) regarding aspects of one’s performance or understanding” (p. 102). Most educators understand formative feedback as a way to help students understand where they are and how to hit a learning target. In this vein, Hattie and Timperley (2007) propose three questions for teachers to consider: “where am I going? How am I going? and Where to next?” (p. 102).

Unfortunately, much of the education system seems to be built on a summative assessment model. A mark on a test does not give the student any opportunity for revision and growth. Even rubric assessments are mostly summative. A student can determine why they received a final grade, but there is rarely a way to improve it. High-quality formative feedback, on the other hand, can encourage motivation and self-regulation. Nicol and Dick’s (2006) synthesis of the literature led them to formulate seven guiding principles for good feedback practices:

- helps clarify what good performance is (goals, criteria, expected standards);

- facilitates the development of self-assessment (reflection) in learning;

- delivers high quality information to students about their learning;

- encourages teacher and peer dialogue around learning;

- encourages positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem;

- provides opportunities to close the gap between current and desired performance;

- provides information to teachers that can be used to help shape teaching. (p. 205)

Feedback must consider the nature and quality of the message, the characteristics of the instructional context and the characteristics of the learner (Narciss & Huth, 2004). Teachers must be thoughtful about the purpose and nature of the feedback they are giving. How will it be used? How will it affect student self-efficacy, motivation, and their ability to learn?

A number of studies have focused on the role formative feedback has on helping students self-regulate their learning (Cakir, et al., 2018; Nocol & Dick, 2006). Xiao and Yang (2019) identify how formative assessment can help students play an active role in their learning, set learning goals, evaluate their performance against learning targets and take action to improve their work. In his seminal work on formative feedback, Sadler (1989) recognizes the importance of learners self-monitoring and evaluating the quality of their work. Gedye (2010) encourages making self-assessment a part of formative feedback to avoid dependency on instructor feedback alone.

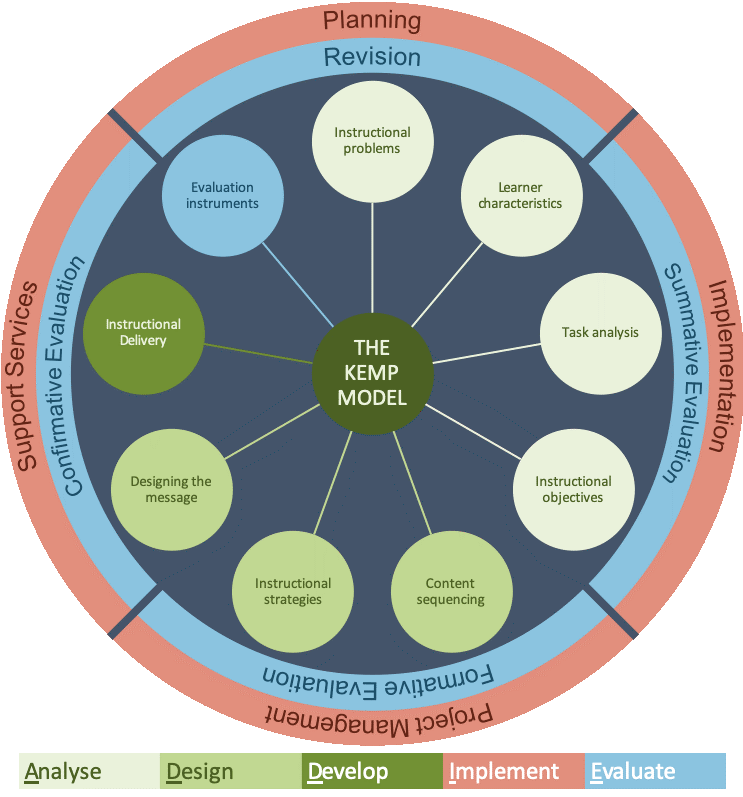

Formative Feedback and the Kemp Model of Instructional Design

McMillan, Venable and Verier (2013) highlight the importance of using formative feedback to not only support student learning, but also inform instructional adjustments. Evaluation and revision processes are ubiquitous in the Kemp Model of Instructional Design (Morrison, Ross, & Kemp, 2004). Due to the holistic and non-linear nature of the model, feedback and revision can happen at any time and are designed as encompassing features of it (Obizoba, 2015). This reflexive model is well-matched with teachers who value regular formative feedback and use it to inform instructional decisions.

Figure 1

The Kemp Model of Instructional Design (World of Work Project, n.d.)

Using New Technologies for Multi-Modal Feedback

When Denton et al. (2008) studied the effectiveness of giving feedback to students electronically in 2008, much of today’s current technological landscape did not exist. They identified the advantages and disadvantages of using standalone systems such as word processors and email. Just thirteen years later, the possibilities for integrating feedback across platforms has evolved substantially. Hung, Chiu and Yeh (2013) identify how new technologies are leading to a re-conceptualization of literacy and the ways we respond to it. Choi and Yi (2016) advocate a multi-modal approach to teaching and learning, particularly as a way of deepening engagement and connecting with students. Takayoshi and Selfe (2016) identify a range of benefits when teachers interact with students on a multi-modal level, including improving engagement, overall digital literacy, and opportunities for meaning-making.

A number of new technologies are creating opportunities for high-quality multi-modal feedback. Who will use them depends on several factors. In their analysis of factors predicting the Pedagogical Digital Competence of teachers, Guillén‑Gámez, Mayorga‑Fernández, Bravo‑Agapito and Escribano‑Ortiz (2020) discuss the importance of regular training and teacher access to resources. According to From (2017), “Pedagogical digital competence relates to knowledge, skills, attitudes and approaches in relation to digital technology, learning theory, subject, context, and the relationships between these” (p. 48). Teachers need access to frequent training and to the digital tools they need in a timely way. Barriers need to be addressed and funding models need to incorporate the use of new technologies.

Application

The following technologies are offered as ways to provide high-quality multi-modal feedback to middle school students about their writing. Where research has been found it has been included. I have also included helpful tips I have learned from my experiences.

Google Workspace for Education

The Google Workspace for Education Apps (Google, n.d., e), are impressive in many ways. They allow a high degree of collaboration amongst users both synchronously and asynchronously. Multiple users can contribute to a single document, offering for a wide range of possibilities. Teachers can offer immediate feedback to students on their writing.

Google Docs

Thre is some good research on Google Docs (Google, n.d., c), an application that provides students with many possibilities. They can use it as a stand alone word processor or collaborate with peers synchronously or asynchronously. Work is saved automatically and Google Docs works seamlessly with Google Read/Write, an important assistive technology extension. Looking at Google Docs in particular, Saman and Rahimi (2019) found positive correlations when instructors worked with students synchronously on their writing through Google Docs, as did Woodrich and Fan (2017). Liu and Yu-Ju (2016) found a lower level of anxiety when students collaborated through Google Docs. Suwantarathip and Wichadee (2014) found that Grade 12 students using Google Docs to write collaboratively appreciated the immediate feedback they received from their peers and high higher scores on their writing.

Helpful Tips:

- It is a good idea to set up some norms or expectations for peer collaboration or revision.

- Model collaborative practices on screen. What does this look like? This is a skill that needs to be modelled.

- Use a different colour to identify different collaborators, or have everyone tag their name.

Google Classroom

Google Classroom is a learning management system widely used by students in Nova Scotia P-12. It works seamlessly with Google Workspace for Education applications that students use daily. Many schools in Nova Scotia require teachers to use Google Classroom (Google, n.d., b), as was the case during the province-wide pandemic shutdown. Google Classroom can be leveraged to provide whole class or small group instruction in various ways. For example, a teacher can easily send a whole class formative feedback in the form of an attachment (document, video, etc) or using the class stream. Most teachers use it as a learning platform to organize units of study or individual lessons.

Helpful Tips:

- Create Topics to organize student materials. This makes everything, including assignments with feedback, more manageable and easier to find.

- Create a Master Classroom to store assignments and rubrics you would like to re-use in the future.

- Regularly check in with students about how you can make the classroom easier to navigate.

Screencastify

One technology garnering a lot of attention is Screencastify (2020), a Google Chrome (Google, n.d., a) extension that allows users to create videos of their screen with commentary. Henry, et al. (2020) found that student perceptions of receiving feedback through Screencastify were very positive and had some clear advantages over receiving feedback in the classroom. Students surveyed indicated “better quality feedback, better understanding of what to do with the feedback, feedback was not intimidating, positive feedback was provided” (p. 46). Some disadvantages students perceived included finding switching between the video and their document cumbersome and the fact that they could not have an immediate back and forth conversation with their teacher. In terms of a traditional student-teacher writing conference, this back-and-forth communication is an important aspect. While this is a limitation, the opportunity to provide detailed feedback through video and audio is very powerful.

Helpful Tips:

- Students have mentioned that seeing my face embedded in the video has helped them feel more connected.

- Be enthusiastic about student writing. This is especially important for students who are not confident. We want to motivate and encourage students.

- Keep videos relatively short. Mention some strengths you are seeing and point out one or two areas to revise.

- Demonstrate with mentor text so students have a clear example.

- Remember to ask open ended questions that help students self-reflect.

- This is a great chance to give a quick mini-lesson on a particular point!

Mote

Mote (Mote Technologies, 2021) is a Google Chrome extension that allows the user to easily add voice notes to a variety of Google Workspace for Education applications.

Helpful Tips:

- Because the main mode of communication is audio, teachers need to be aware of how they are sounding to students. We want students to feel motivated and open to our comments. They don’t have the benefit of seeing our expressions or body language.

- Hot keys can be useful for dropping in voice notes. For example, in Google Docs, select the text you want to comment on and press Ctrl + Alt + M and then click the Mote icon in the comment box.

- Mote has a very useful voice-to-text feature.

Privacy Considerations

Nova Scotia Student Information Policy

With so much student information online, The Government of Nova Scotia has created the Provincial Privacy of Student Information Policy (2016, July) to protect their privacy:

Provincial Privacy of Student Information Policy

Privacy Impact Assessment

The Nova Scotia Department of Education and Early Childhood Education conducted a Privacy Impact Assessment on Google Apps for Education (2015) that can be found here:

Google Workspace for Education

Education bodies around the world are turning to Google and their impressive suite of educational applications. In Nova Scotia, every public school student has access to a Google Workspace for Education account. Teachers, students and parents in Nova Scotia should be aware of the Google Workspace for Education Privacy Notice (Google, n.d., f):

Google Workspace for Education Privacy Notice

Screencasify

Screencasify’s Privacy Policy (2020, a) demonstrates compliance with the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, both American laws. Their privacy policy can be found here:

Conclusions

Providing students with high-quality formative feedback is widely recognized as an essential way to help students learn. Their motivation, self-regulation and learning can all benefit. New ways of giving multi-modal feedback are possible through a range of innovative technologies. These technologies enjoyed widespread adoption during the pandemic as teachers sought new ways to reach students. To use these technologies effectively, however, teachers need an adequate level of pedagogical digital competence. Professional development needs to be directed at helping teachers develop their knowledge and skills. Teachers also need easy access to apps they want to try. The fewer barriers there are, the more these technologies will be adopted and experimented with.

While many students have excellent access to the internet and digital tools like smartphones, laptops and tablets, many do not. Teachers and the public need to advocate on behalf of students for equal access. It doesn’t matter what technologies are available for teachers to use if kids can’t access the feedback.

While students have overwhelmingly given positive feedback when teachers use technology like Screencastify, we do need to be aware of limitations. Synchronous back and forth communication is an important aspect of writing conferences that move students forward, as it allows students to ask questions, communicate their thinking and clarify teacher comments.

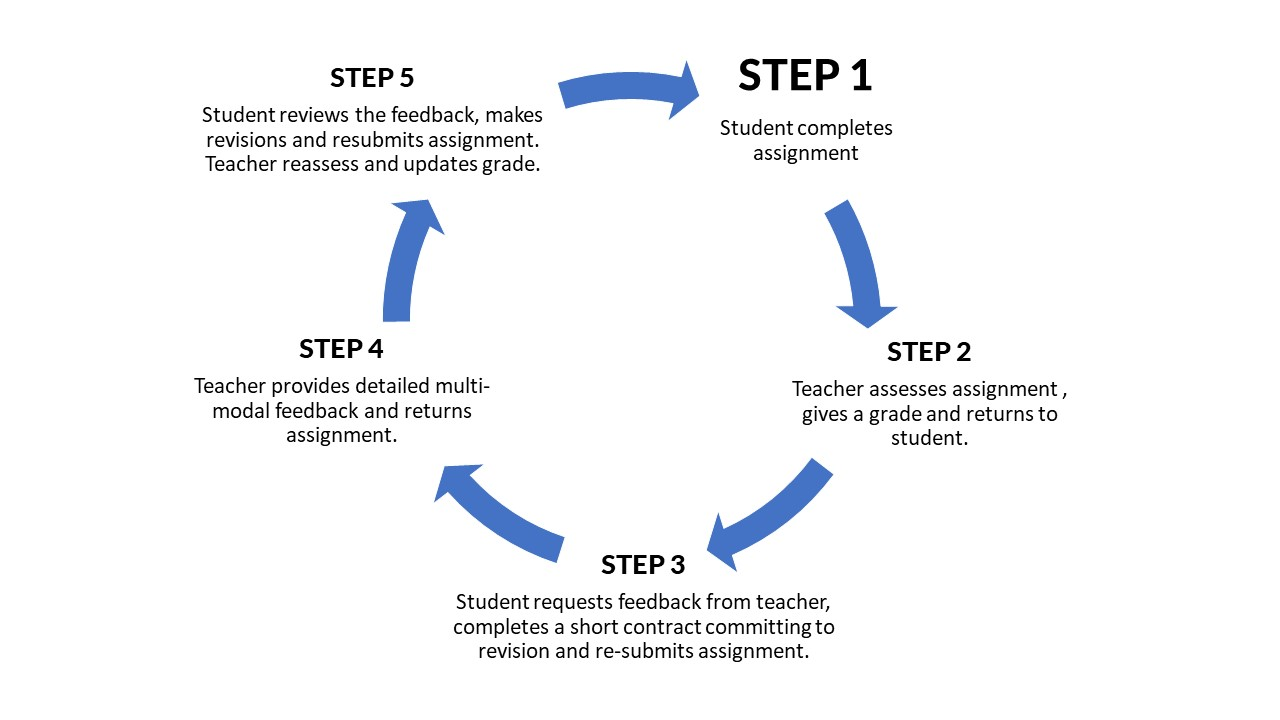

Time is also a critical factor for teachers to consider. On average, a writing teaching may spend about ten minutes reading and giving feedback for a three-page narrative. If the teacher has four classes of twenty-five students, this would equal sixteen hours of time. As there is little time during the school day to give detailed feedback, most of this comes from home time. Compounding this issue is the fact that some students do not value or use formative feedback. About sixty percent of my students make revisions to final drafts after being given detailed multi-modal formative feedback, leaving fourty percent of my time arguably wasted. As a result, I now require students to ask for feedback on such a piece before actually giving it. This is Step 3 of a process I use, as can be seen in Figure 2, and has allowed me to save countless hours of precious time. We do not want to create a dependency, and student effort needs to reflect the teacher’s.

Figure 2

Formative Feedback Steps

This process is not meant to limit the flexibility teachers have in giving frequent formative feedback. It is meant more for final pieces of writing that require significant time and effort to mark. Teachers can give feedback at any time and adapt their instruction to reflect student need. If many students in the class are asking, for example, about how to use strong verbs and limit adverbs in narrative writing, I know it is time for a whole class lesson. If a few students are not using punctuation correctly, a small group lesson is appropriate.

This process is not meant to limit the flexibility teachers have in giving frequent formative feedback. It is meant more for final pieces of writing that require significant time and effort to mark. Teachers can give feedback at any time and adapt their instruction to reflect student need. If many students in the class are asking, for example, about how to use strong verbs and limit adverbs in narrative writing, I know it is time for a whole class lesson. If a few students are not using punctuation correctly, a small group lesson is appropriate.

Providing multi-modal feedback to students is a powerful way to reach them. This is especially for students who are neurodiverse. In my classes I have students who have deficits in working memory, attention, processing speed and phonological reasoning. These students can play a teacher generated video about their writing as many times as they like. They can control the flow of information and review it with another professional (e.g., Speech Language Pathologist, Learning Disability Specialist, Resource Teacher) or with their parents. If a student is having a difficult day and is struggling to focus, they can choose a time when they are more regulated to review the video. These are some of the obvious benefits of multi-modal digital feedback.

The technology available to teachers to do this will continue to evolve. Looking to the future, Goldin, et al. (2017) indicate that “the social organizations and technologies we create to provide and improve formative feedback will continue to advance rapidly” (p. 390). They highlight the emerging technology of Virtual Reality and artificial intelligence. These new methods of interacting with students and providing feedback will no doubt be fascinating and hold promise. Teachers, students and parents will need support to access and grow comfortable with them. Education systems need to take a central role in facilitating this and advocating for equal access to technology for all learners.

References

Cakir, R., Korkmaz, Ö., Bacanak, A., & Arslan, Ö. (2018). An exploration of the relationship between students’ preferences for formative feedback and self-regulated learning skills. MOJES: Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 4(4), 14-30. https://ejournal.um.edu.my/index.php/MOJES/article/

view/12671

Choi, J., & Yi, Y. (2016). Teachers’ Integration of Multimodality Into Classroom Practices for English Language Learners. TESOL Journal, 7(2), 304–327. https://doi-org.qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/10.1002/tesj.204

Denton, P., Madden, J., Roberts, M., & Rowe, P. (2008). Students’ response to traditional and computer‐assisted formative feedback: A comparative case study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(3), 486-500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00745.x

From, J. (2017). Pedagogical Digital Competence–Between Values, Knowledge and Skills. Higher Education Studies, 7(2), 43-50. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v7n2p43

Gedye, S. (2010). Formative assessment and feedback: A review. Planet, 23(1), 40-45. http://dx.doi.org/

10.11120/plan.2010.00230040

Goldin, I., Narciss, S., Foltz, P., & Bauer, M. (2017). New directions in formative feedback in interactive learning environments. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 27(3), 385-392. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs40593-016-0135-7

Google (n.d. a). Google Chrome: Get more done with the new Chrome. [Web page]. https://www.google.com/intl/en_ca/chrome/

Google (n.d. b) Google Classroom. [Webpage]. https://classroom.google.com/

Google (n.d. c). Google Docs: About. [Web page]. https://www.google.ca/docs/about/

Google (n.d. d) Google Meet. [Webpage]. https://meet.google.com/

Google (n.d. e) Google Workspace for Education Overview. [Web page]. https://edu.google.com/intl/en_ca/products/workspace-for-education/

Government of Nova Scotia. (2016, July). Provincial Privacy of Student Information Policy. [PDF file]. https://www.ednet.ns.ca/docs/privacyofstudentinformationpolicy.pdf

Graham, S., Hebert, M., & Harris, K. R. (2015). Formative assessment and writing: A meta-analysis. The Elementary School Journal, 115(4), 523-547. https://doi.org/10.1086/681947

Guillén-Gámez, F. D., Mayorga-Fernández, M. J., Bravo-Agapito, J., & Escribano-Ortiz, D. (2020). Analysis of teachers’ pedagogical digital competence: Identification of factors predicting their acquisition. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-019-09432-7

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F003465430298487

Henry, E., Hinshaw, R., Al-Bataineh, A., & Bataineh, M. (2020). Exploring Teacher and Student Perceptions on the Use of Digital Conferencing Tools When Providing Feedback in Writing Workshop. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 19(3), 41-50. https://files.eric.ed.

gov/fulltext/EJ1261313.pdf

Hsueh-Jui Liu, & Yu-Ju, L. (2016). Social constructivist approach to web-based EFL learning: Collaboration, motivation, and perception on the use of google docs. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 19(1), 171-186. https://search-proquest-com.qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/scholarly-journals/social-constructivist-approach-web-based-efl/docview/1768612692/se-2?accountid=12378

Hung, H.-T., Chiu, Y.-C. J., & Yeh, H.-C. (2013). Multimodal assessment of and for learning: A theory-driven design rubric. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(3), 400–409. https://doi-org.qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01337.x

Moreno, R. (2004). Decreasing cognitive load for novice students: Effects of explanatory versus corrective feedback in discovery-based multimedia. Instructional Science, 32, 99–113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:TRUC.0000021811.66966.1d

Morrison, G. R., Ross, S. M., & Kemp, J. E. (2004). Designing effective instruction, 4th edition, John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Mote Technologies, Inc. (2021). Mote. [Web page]. https://www.justmote.me/

Nova Scotia Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (2015). Privacy Impact Assessment: Google Apps for Education. [PDF file]. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7Ev_gwf02s2RG5xM1M5d3VaekU/view

Obizoba, C. (2015). Instructional Design Models–Framework for Innovative Teaching and Learning Methodologies. International Journal of Higher Education Management, 2(1). https://ijhem.com/cdn/

article_file/i-3_c-22.pdf

Narciss, S., & Huth, K. (2004). How to design informative tutoring feedback for multimedia learning. Instructional design for multimedia learning. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/

228749053_How_to_design_informative_tutoring_feedback_for_multi-media_learning

McMillan, J. H., Venable, J. C., & Varier, D. (2013). Studies of the effect of formative assessment on student achievement: So much more is needed. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.7275/tmwm-7792

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane‐Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self‐regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in higher education, 31(2), 199-218. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03075070600572090

Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18(2), 119-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00117714

Screencastify (2020 a). Privacy Center. [Web page]. https://www.screencastify.com/privacy

Screencastify (2020 b). Video for everyone. [Web page]. https://www.screencastify.com/

Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of educational research, 78(1), 153-189. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0034654307313795

Suwantarathip, O., & Wichadee, S. (2014). The Effects of Collaborative Writing Activity Using Google Docs on Students’ Writing Abilities. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 13(2), 148-156. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1022935.pdf

Takayoshi, P., & Selfe, C. L. (2007). Multi-Modal Composition (C. Selfe, Ed). [PDF file]. Hampton Press. http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/students/envs3100/selfe2007.pdf

Woodrich, P., Megan, & Fan, Yanan. (2017). Google Docs as a Tool for Collaborative Writing in the Middle School Classroom. Journal of Information Technology Education, 16, 391-410. http://dx.doi.org/10.28945/3870

Xiao, Y., & Yang, M. (2019). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: How formative assessment supports students’ self-regulation in English language learning. System, 81, 39-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.01.004