Lori Ann Feltham

Author

Lori Ann Feltham

Affiliation

Cape Breton University

Abstract

This literary review examines inquiry-based learning in an online setting. Within elementary schools, especially in primary grades (Kindergarten through three), play and inquiry-based learning is an encouraged learning process to facilitated in physical classrooms. However, there is little information on how to use this process when applied to an online setting for this demographic. To apply it to distance or online education, the constructivist model will be explored, and the principles of what makes inquiry learning will be examined. Social interaction and opportunities to share experience is how meaning is constructed according to the learning theory at hand. Both synchronous and asynchronous systems will be considered for collaboration, and Moore’s (1989, 1991) model for the theory of instructional distance will show how dialogue and structure is balanced in a constructivist online course design. Breaking down the elements of inquiry-based learning and presenting supportive research will help build understanding of application when the virtual primary classroom replaces the physical one.

Keywords

Inquiry-based learning, constructivist theory of learning, asynchronous setting, synchronous setting, distance education, online learning

Overview

Inquiry-based learning for the primary classroom – A literature review. (08:58)

Inquiry-based learning for the primary classroom – A literature review. (08:58)

Introduction

In an elementary school setting, inquiry-based learning has become a popular learning process. Within the four walls of the classroom, learning environments are set up to encourage students to interact with one another, engage in conversations, and spark curiosity. This follows the constructivist’s theory that meaning is constructed through both social interaction and personal experience (Ammenwerth, 2018). Students are therefore encouraged to share, discuss, and lead conversations. This practice is student-centered, and the teacher’s role is to guide students through inquiry to ensure outcomes are achieved. However, when the spread of the COVID-19 virus threatened the safety of our students, the physical classroom environment was no longer open to create opportunities for learning collaboratively. Teachers were forced to move classrooms online. And therefore, it seems more important than ever to understand how we can design and facilitate inquiry-based learning environments through technology that will allow students to participate in experiences that build meaning.

The study of online learning design is not new, nor is inquiry-based learning, however few cases of student-centered learning design look at technology and inquiry-based instruction (Dondlinger, 2021). As play and inquiry-based learning are encouraged in elementary schools, this literary review will explore the learning concepts and how they can be used for online instruction.

Literature Review

Constructivists Theory

The constructivist’s theory is an approach to learning that promotes learning as a constructive and social process. Learning is achieved when interaction and cooperation between the teacher and students takes place in a supportive environment (Ammenwerth et al., 2018). Ammenwerth et al. (2018) state that gradual construction of learning will lead to shared meaning, therefore there must be opportunities in an online setting for students to connect and build these shared experiences for the learning process to work best. According to Dondlinger (2021), constructivist learning theory follows three principles. Dondlinger (2021) states that learning is a result of both exploring personal experience and exploring other’s perspectives. That’s why collaboration is key in its process. Furthermore, it “is an active process occurring in realistic and relevant situations” (Dondlinger, 2021, p. 3).

While most of the literature supports inquiry-based learning as a process stemming from the constructivist theory, Schlesinger et al. (2019) believes that when applying the constructivist theory to an online context, it is best to use a metacognitive approach supported by the constructivist approach. A metacognitive approach encourages students to reflect and challenge their own views when faced with new ideas. Schlesinger et al. (2019) believes a combination of the two approaches allows for collaboration amongst novice and experts. These experiences of conversation and activity will then encourage students to look at their own understanding and challenge their own perspectives (Schlesinger et al., 2019).

While there is some debate on whether inquiry-based learning should be built off of a pure theory of learning or a blend, there is no debate that social interaction is imperative to its success. So how then, can we build the same social and collaborative opportunities online as there are in a physical classroom? How is this facilitated online? What are the challenges?

Interactions Online

Studies have shown that cooperative learning can lead to many advantages when practiced online. When students learn within a trusted community, effective and successful learning practices are created and there is a decrease in dropout rates (Ammenwerth et al., 2018). These cooperative learning communities increase student engagement, motivation, and can improve meta-cognitive and social skills along with increased knowledge retention (Ammenwerth et al., 2018). The benefits of inquiry and social interaction are dependent on the presence of both student and teacher, and how these interactions are promoted and accessed (Dondlinger, 2021).

Fallon (2011) supports these claims. He describes a virtual classroom as a synchronous online learning environment. The synchronous system is not only a place where instructional materials are available, it supports live interactions between students and teachers. Learning tools and opportunities for contextual discussion are required for its success. Interaction between students and teachers in this type of system, if performed regularly, will improve student attitudes towards learning. It also creates rich learning communities, improves motivation to complete assignments, academic performance, as well as retention rates (Falloon, 2011). These statements are further supported by additional research in which synchronous environments provide opportunities for teachers to monitor student understanding and provide prompt feedback in real time. This assessment of learning can allow instructors to make alterations in course design or provide students additional intervention and support (Schullo et. al., 2007). Furthermore, a synchronized environment encourages two-way communication and therefore encourages more dialogue (Fallon, 2011).

Mary Jo Dondlinger (2021) examined qualitative data through a case study while designing a Master of Education Course that examined the role of technology in inquiry-based instructional methods on technology-supported learning. Her goals were to investigate the context, challenges, and product of this course with its participants within technology and inquiry-based learning. She felt it was important to follow pure constructivist theory and ensured her course was student-led and rich with discussion. This brought her some difficulty. As she designed the course, she found she needed to add deadlines to discussion posts in order to promote timely discussion. This in turn, may inhibit the natural flow of discussion and participation and proved to be difficult in a synchronous environment. Instead, contrary to Fallon’s beliefs, the benefits of asynchronous online discussion promoted more participation. She found everyone had a turn to speak and felt heard without the pressure of larger groups. Additionally, the extra time it took to facilitate asynchronous discussions gives students an opportunity to think their answers over. This leads to making more personal connections and constructing relevant meaning. However, there was difficulty in maintaining constructivists’ learning theory as it hindered opportunities to consider multiple perspectives. Without multiple points of view, the discussion lacked the rich social environment necessary for student-led discussions and negotiating meaning (Dondlinger, 2021).

Inquiry-Based Learning

Inquiry-based learning requires students to become active participants in their understanding. It varies from traditional instruction where the teacher provides lectures for student understanding. Within play or inquiry-based learning, learning is guided by the teacher, while the student explores the knowledge on their own. In order for this to be effective, there must be an environment that encourages students to explore knowledge and spark curiosity. Dondlinger (2021) shares that there are four principles of student-centered learning environments formulated by Land, Hannifin, and Oliver (2012):

- The centrality of the learner in defining their own meaning

- Scaffolded participation in authentic tasks and sociocultural practices

- Importance of prior and everyday experiences in meaning construction

- Learning is enriched via access to multiple perspectives, resources, and representations

Crawford et al. (2005) confirms these principles as they explore scientific inquiry and the subject of evolution using technology and inquiry-based learning in their study. They believed that by providing students with a common authentic experience through this learning process and technology, students would earn a more enhanced perspective. They concluded that they were correct – by creating an interactive environment rich in discussions of inquiry, performance was improved (Crawford et al., 2005).

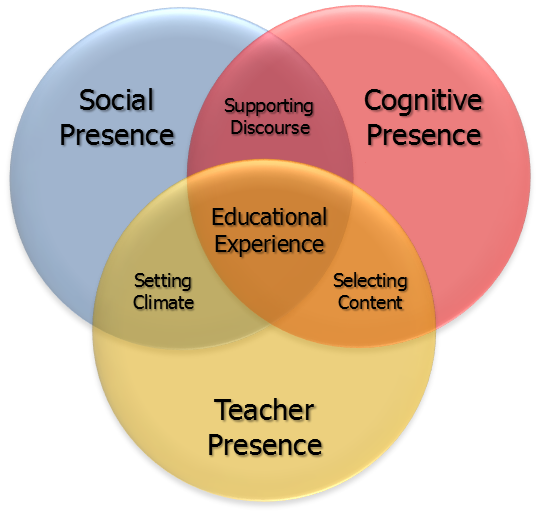

Ammenwerth et al. (2018) found similar findings in their own investigation of designing an online course. In their design, they followed the Community of Inquiry (CoI) model (Athabasca University, n.d.; Dron & Anderson, 2014; Garrison, et al., 2000). As illustrated in Figure 1, the CoI model describes principles critical to the success of inquiry-based cooperative learning as cognitive, social, and teaching presence. The cognitive presence is a student’s ability to construct meaning through their communication with others and their own point of view. The social presence refers to a trusting environment that encourages participant communication and creating a shared identity as a group. The social presence allows students to develop interpersonal skills and relationships. Finally, the teaching presence refers to the design of the course and how the instructor facilitates and guides understanding and student discussion that creates strong understanding of the desired outcomes (Ammenwerth et al., 2018).

Figure 1:

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) model (adapted from Athabasca University, n.d.)

The principles described in both the Community of Inquiry model and Land, Hannifin, and Oliver’s (2012) four principles of student-centered learning environments, give us the opportunity to consider how all of this is put into practice. Inquiry-based learning in an online design that has different challenges than other learning approaches. With the importance of social interaction and a rich learning environment being imperative to its success, how is it possible to create this learning environment when you remove the physical space?

Inquiry-Based Learning Online

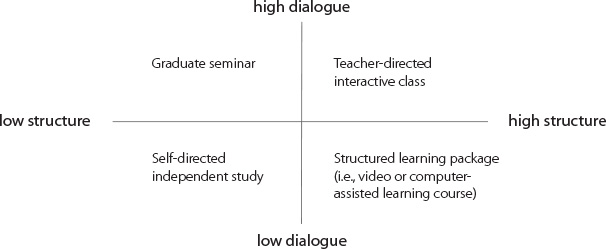

Moore’s (1989, 1991) theory of instructional distance has become very popular in its influence on distance education courses and the research surrounding it (Anderson & Dron, 2014). The model describes the effects that interactions have on the behaviour of its participants. It examines how to mix both social-constructivist and structured learning into one and runs off the assumption that learning must take place both formally and informally, whether it is over distance or in the classroom. Moore (1989, 1991) claims that distance in these terms should not be considered over time or geography but measured throughout structure and communication between the students and teacher. He says that transactional distance can be measured on a continuum and the instructional designer can manipulate the amount of dialogue and structure of the course (Anderson & Dron, 2014). This manipulation of variables will determine where they are placed within the four quadrants as seen in Figure 2 below. While the model assures us that learning still takes place no matter where a distance educational course falls on the continuum, we can again see the difficulty in designing highly communicative and active environments in a virtual space, as briefly described earlier with Mary Jo Dondlinger’s (2021) case study.

Figure 2:

The four quadrants of Transactional Distance (from Dron & Anderson, 2014, p. 43)

Ammenwerth (2018) describes the benefit of virtual learning is that it can take place anywhere at any time, which supports lifelong learning. However, its disadvantage is a by-product of just that: learning in isolation. Where learning asynchronously provides students and teachers with incredible flexibility, it doesn’t provide the sense of community and social engagement that comes with synchronous interaction or face-to-face discussion.

Dondlinger (2021) details several difficulties that come with designing online inquiry-based courses. The balance of creating content for the course and creating student opportunities to curate their own is at the top of her list. And creating authentic learning opportunities online can create issues for the designer. It is important that students are open-minded and want to share their perspectives. Time restraints can create pressure to perform and therefore hinder authentic student inquiry. Dondlinger (2021) also brings up the issue of formal assessment. Many online courses require examinations. Assessment restrictions prevent true inquiry.

Conclusions

While there was an adequate amount of research that looked at inquiry-based learning online, there was very little found concerning young students using online learning based on inquiry. While the research found can be applied to general learning, primary students in particular with limited digital literacy skills have not been represented. This particular demographic has participated in the inquiry-based learning process in our schools and have now been participants in online distance education over the past years. It is more important than ever that we understand how to design rich learning environments in online courses that will guide our students to deep understandings and shared perspectives for learning.

In exploration of the literature there seems to be a consistent struggle in the ability to apply true play or inquiry-based instruction to an online format. Removing the physical space of the classroom can remove some of the opportunity for students to lead inquiry and learn from each other. Perhaps the distance itself is naturally what prevents students from participating in socially constructed learning opportunities on par to what can happen in a traditional classroom. Regardless, there is no question that online learning is here to stay. While we may sacrifice some of the benefits of in-person learning when we use only online education, we are also gaining the opportunity to learn when distance is problematic. So perhaps it is pointless to wallow in what inquiry-based learning cannot do for us online, but what it can. It can still be achieved.

References

Ammenwerth, Hackl, W. O., Felderer, M., Sauerwein, C., & Hörbst, A. (2018). Building a Community of Inquiry Within an Online-Based Health Informatics Program: Instructional Design and Lessons Learned. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 253, 196–200.

Anderson, T., & Dron, J. (2014). Teaching crowds: Learning and social media. Athabasca University Press.

Athabasca University (n.d.). CoI Framework. https://coi.athabascau.ca/coi-model/

Crawford, Zembal-Saul, C., Munford, D., & Friedrichsen, P. (2005). Confronting prospective teachers’ ideas of evolution and scientific inquiry using technology and inquiry-based tasks. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 42(6), 613–637. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20070

Dondlinger. (2021). Technology and Inquiry-Based Instructional Methods: A Design Case in Student-Centered Online Course Design. International Journal of Designs for Learning, 12(2), 93–110. https://doi.org/10.14434/ijdl.v12i2.29583

Falloon (2011). Making the Connection: Moore’s theory of transactional distance and its relevance to the use of a virtual classroom in Postgraduate online teacher education. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 43(3), 187-209. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2011.10782569

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. http://cde.athabascau.ca/coi_site/documents/Garrison_Anderson_Archer_Critical_Inquiry_model.pdf

Moore, M. (1989). Three types of interaction. The American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1-6.

Moore, M. (1991). Editorial: Distance education theory. The American Journal of Distance Education, 5(3), 1-6. http://www.ajde.com/Contents/vol5_3.htm#editotial

Schellinger, Mendenhall, A., Alemanne, N., Southerland, S. A., Sampson, V., & Marty, P. (2019). Using Technology-Enhanced Inquiry-Based Instruction to Foster the Development of Elementary Students’ Views on the Nature of Science. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 28(4), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-019-09771-1