Globally, many countries are contending with how to make multiple information systems across the health care domain “speak the same language.” This ability of applications and systems to connect and share health information—to interoperate—supports important capabilities, including continuity of care, health system management and surveillance, and the financial transaction processing needed to support UHC and monitor progress of UHC initiatives.[1] Thus, eHealth infrastructure, interoperability and standards, and UHC initiatives are inextricably intertwined.

If the key messages of this eBook had to be summarized in a single core piece of advice, it would be that a common, standards-based, national-scale eHealth infrastructure should support both care delivery and financial payments workflows as well as produce the analytics necessary to monitor and manage these.

This eBook is grounded in the JLN’s prior work to develop guidance and tools on the subject of interoperability of health insurance information systems. A first step a country should consider when planning for interoperability is the creation of a health data dictionary (HDD) to define and document common terminology. An HDD supports consistent, accurate, and systematic data definitions, which become extremely valuable when planning how organizations and systems will collect and exchange information. This topic is explored further in a JLN paper titled Promoting Interoperability of Health Insurance Information Systems through a Health Data Dictionary, available on the JLN website.[2] The JLN also developed the openHDD tool, which is a freely available, collaborative, web-based, open-source tool for creating data dictionaries in general and HDDs in particular. The tool contains HDDs from several countries, which can be used as examples or starting points in defining a dictionary, and is available on the JLN website.[3]

The need for interoperability of health information systems is well stated by the UN Commission on Information and Accountability:

The use of eHealth and mHealth [mobile health] should be strategic, integrated and support national health goals. In order to capitalize on the potential of ICTs, it will be critical to agree on standards and to ensure interoperability of systems. Health Information Systems must comply with these standards at all levels, including systems used to capture patient data at the point of care. Common terminologies and minimum data sets should be agreed on so that information can be collected consistently, easily and not misrepresented. In addition, national policies on health-data sharing should ensure that data protection, privacy, and consent are managed consistently. [4]

In many countries, health care providers and facilities are not yet using electronic information systems. In such a context, connectivity among systems is not an initial concern and is often not a high priority for policymakers. However, as the use of ICT inevitably grows and the cost to a nation for supporting UHC grows, system-to-system interoperability increasingly becomes a concern for all the providers, patients, payors, and policymakers who need data from information systems to monitor and manage health services. By establishing a standards-based approach early in the process, a network effect can be created that unlocks value from the many individual, disparate investments in eHealth and mHealth. Communication between providers, payors, policymakers, and even patients is critical to enabling transactions across the national health system to support care delivery, provider payments, and the generation of important health and health system metrics.

Interoperability between disparate health applications relies on the adoption of standards. Various chapters in this eBook:

- Outline the value proposition behind national-scale, eHealth infrastructure in a way that policymakers and IT professionals alike can readily understand.

- Provide examples of key implementation issues faced by countries on the journey toward developing national-scale, standards-based eHealth infrastructure and how they dealt with them.

- Introduce four key stakeholders—patients, providers, payors, and policymakers (the four P’s)—and their differing perspectives on the care delivery value chain.

- Describe a “storytelling approach” that may be employed to develop eHealth standards specifications appropriate to a country’s interoperability requirements.

- Provide a set of practical steps forward that a country may follow to develop this framework.

Although this eBook presents user stories and examples specifically related to UHC, its how-to guidance is generally applicable to any country addressing interoperability between health information systems.

Understanding Key Concepts

Let’s begin with some definitions and context of common terms and concepts used throughout this book.

WHO defines eHealth as “the use of information and communication technologies for health.”[5] And what is eHealth infrastructure? It is the collection of applications, databases, and networks that support sharing of health information. For the purposes of this eBook, we use the term eHealth to denote the full gamut of health-related ICT, including care delivery systems, insurance systems and health system management, and reporting and surveillance systems.

This broad use of the term “eHealth” underscores the eBook’s main message. Wherever a country may be on its eHealth journey and whatever its infrastructure implementation agenda, financial payment mechanisms should be considered a key requirement during the analysis and design phase of any new care-focused initiative, even if today those payments are covered by other sources (e.g., donors). Likewise, as UHC initiatives are launched and payment processing systems are being planned, ICT requirements related to care delivery should be taken into account. An eHealth infrastructure must be a bridge between the policies that apply to care delivery and those that apply to health system financing. It is expected that this shared infrastructure will also support the data analytics that enable disease surveillance, public health reporting, UHC progress monitoring, and overall health system management. As we will see in the chapters that follow, there is a high degree of commonality between the ICT assets needed to support these related sets of requirements and each of the actors in the system.

A definition for eHealth interoperability has been developed by the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society:

In healthcare, interoperability is the ability of different information technology systems and software applications to communicate, exchange data, and use the information that has been exchanged. Data exchange schema and standards should permit data to be shared across clinicians, lab, hospital, pharmacy, and patient regardless of the application or application vendor. Interoperability means the ability of health information systems to work together within and across organizational boundaries in order to advance the health status of, and the effective delivery of healthcare for, individuals and communities. [6]

This book is focused on how eHealth standards can be leveraged to support national interoperability among multiple systems. There is a crucial point that must be appreciated: there is no interoperability without standards. Some could argue that a point-to-point integration between two systems can be implemented without either party adopting standards—and this is true. Interoperability, however, can be thought of as many-to-many integration where the integrating parties do not know ahead of time with whom they will be connecting. To do this, there must first be agreement regarding how the connectivity will be achieved. This pre-agreement is accomplished via the adoption of standards.

Value Proposition for an eHealth Infrastructure

Many countries find themselves in the situation of having numerous disparate systems deployed that are not based on the same eHealth standards (and some are not based on any standard at all). These countries have many eHealth implementations, but they are pilot projects that cannot scale and “islands of automation” that are unable to share data.

A frustrating situation such as this can be avoided or addressed by developing and specifying a NeSF and eHealth architecture.[7] The NeSF provides a way to achieve interoperability among disparate applications, and the eHealth architecture describes the ICT assets that currently exist or should exist to execute the workflows and processes of the health system. As a fundamental starting point, countries must determine where and how eHealth infrastructure will be implemented. To inform this decision, it is useful to trace the role standards-based eHealth infrastructure plays in supporting the overall health production system.

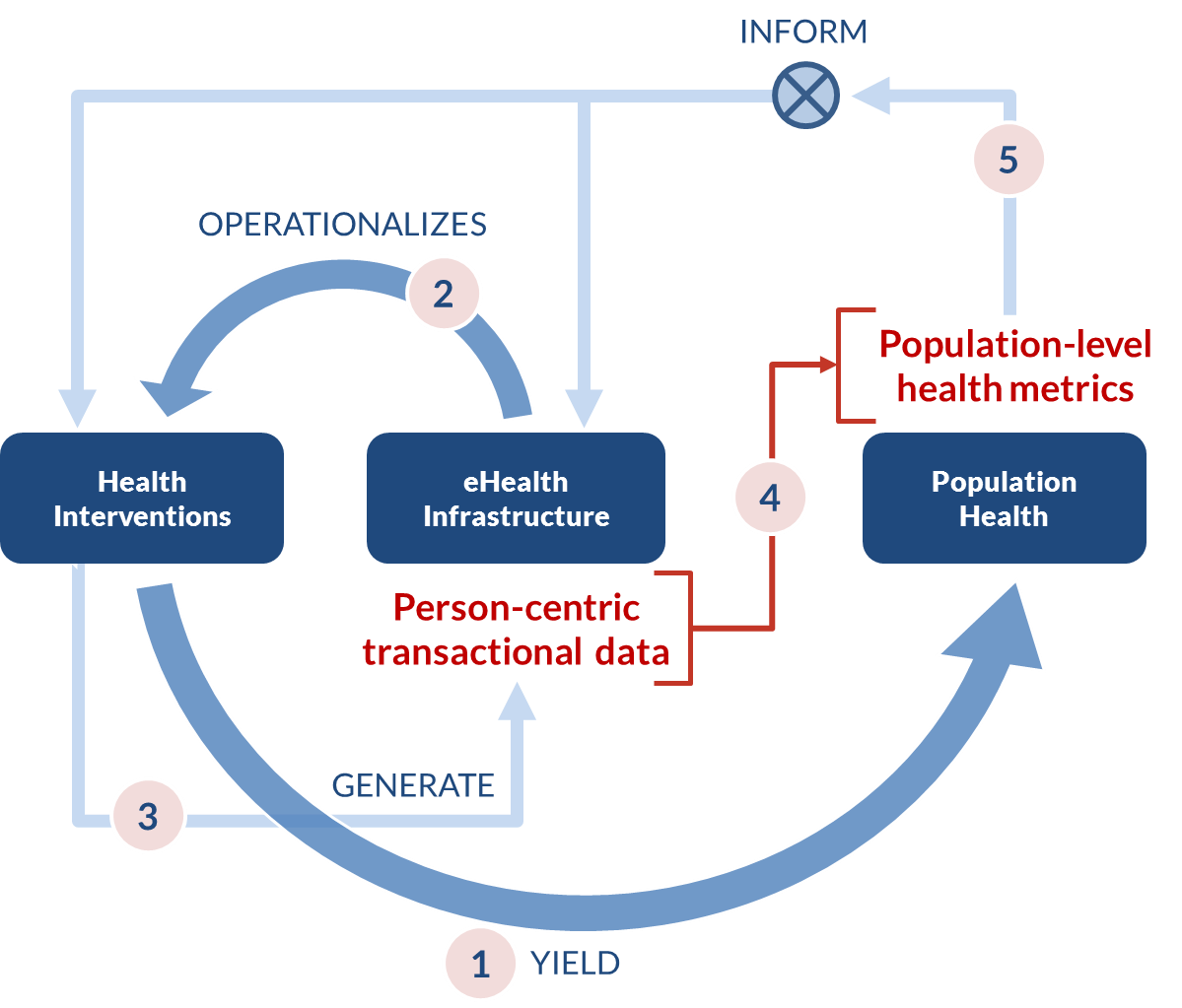

Figure 1 illustrates a model of how eHealth affects population health. To see the Figure 1 video, click the play button in the graphic below or follow the link here: https://vimeo.com/108627029.

As shown in Figure 1:

- Health interventions yield population health.

- eHealth infrastructure operationalizes, or puts into effect, health interventions (e.g., information systems that support care delivery and financial payments).

- Health interventions generate person-centric transactional data (e.g., electronic health records and claims records).

- Person-centric transactional data may be aggregated to develop population-level health metrics.

- Population-level metrics guide the development of new health interventions and the eHealth infrastructure that will operationalize them.

As shown by Figure 1, the eHealth infrastructure plays two key roles. First, it helps measure the health system’s performance. Person-centric transactions—if they are captured in a standards-based, computable format—provide consistent, comparable data that can be collected and analyzed to determine how a nation is doing in delivering health care services and paying providers for services rendered.

Second, the eHealth infrastructure provides a mechanism to exert process control, or feedback, upon the very system it measures. This idea of a feedback loop is at the heart of the World Bank’s “control knobs” model of health system management[8] and the US National Institute of Health’s concept of a “learning health system.”[9] A health system that is metered and has feedback (and “feed-forward”) process control loops can set itself on a path of continuous quality improvement. This can be incredibly effective over time.

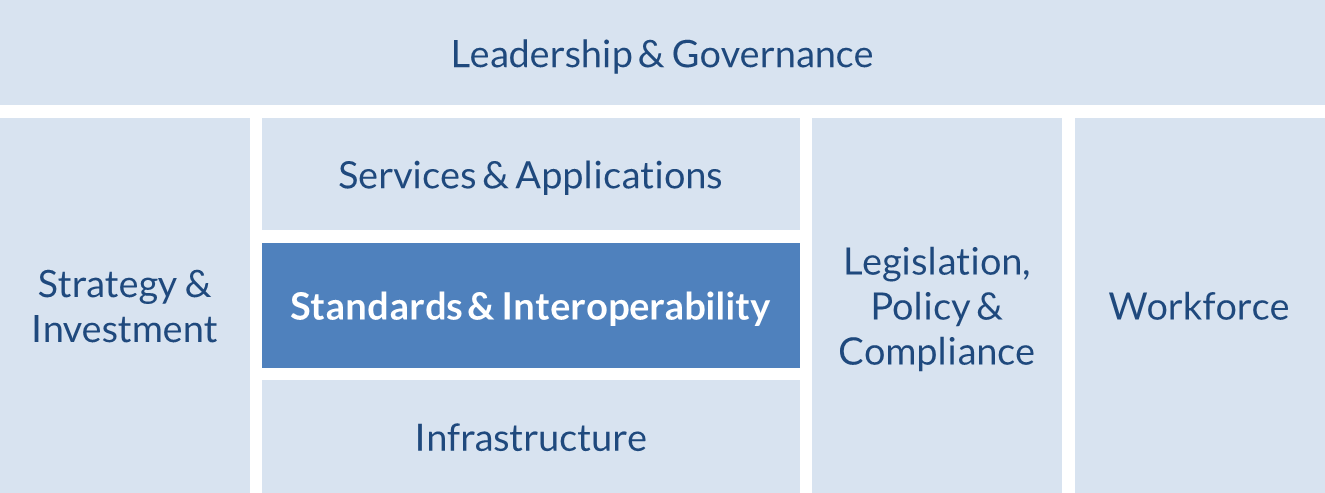

Fully realizing the investment value requires taking steps to operationalize the eHealth strategy, and a NeSF is a critical part of that strategy. In June 2012, the WHO and the International Telecommunication Union (WHO-ITU) National eHealth Strategy Toolkit[10] (henceforth referred to as “the WHO-ITU Toolkit”) was released. It recommended a step-by-step process to establish and document a NeSF that supports both care delivery and UHC-focused workflows. Figure 2 shows the context of the NeSF in relation to the other foundational elements of a national eHealth strategy.[11]

The NeSF is illustrated by the “Standards & Interoperability” block, which is only one of a number of foundational building blocks needed to operationalize a national eHealth strategy. Overarching any eHealth strategy initiative is the all-important leadership and governance, which oversees strategy and investment, the legislative and policy frameworks, the people who will implement the system, and those who will use it. The operational elements are also under the purview of the strategy’s leadership and governance; these include the NeSF and the standards-based services, applications, and infrastructure that “make it go.” All these are covered in more detail in the WHO-ITU Toolkit.

The eHealth infrastructure “footprint” and maturity differ by country. In some countries, eHealth investments are highly fragmented, focused on primary care delivery, and funded by multiple sources. In others, the investments are being driven by UHC initiatives addressing health financing. Although these investment strategies might logically be divided into chronological phases, in reality the investments are usually being made simultaneously with few linkages between them, despite needing similar data and infrastructure.

Regardless of the starting point, each country needs to:

- Articulate a health strategy.

- Articulate an eHealth strategy, aligned with the health strategy and sensitive to the existing eHealth landscape.

- Develop an implementation plan for national eHealth infrastructure that operationalizes the strategy.

- Secure funding to implement the plan.

To illustrate how these steps work in practice, experts from five countries provided background on how this process unfolded in their home country and lessons they learned from the experience. Insights from these interviews are discussed in the following chapter.

- World Bank. Monitoring progress towards universal health coverage at country and global levels: framework, measures and targets. Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 2014. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2014/05/19631447/monitoring-progress-towards-universal-health-coverage-country-global-levels-framework-measures-targets. ↵

- PATH. Promoting Interoperability of Health Insurance Information Systems Through a Health Data Dictionary. A series by Dennis J. Streveler and Cees Hesp. Seattle: PATH; 2012. Available at: http://jointlearningnetwork.org/uploads/files/resources/HealthDataDictionarySeries_8.5x11.pdf. ↵

- Page on openHDD. JLN website. Available at: http://www.openhdd.org/. ↵

- United Nations. Keeping promises, measuring results, First report of the UN Commission on Information and Accountability. New York: United Nations; 2011. Page 14. ↵

- Page on eHealth. World Health Organization website. Available at: http://www.who.int/ehealth/en/. ↵

- Page on the definition of interoperability. HIMSS Website. Available at: http://www.himss.org/library/interoperability-standards/what-is?navItemNumber=17763 ↵

- An excellent overview of health enterprise architecture was published by the Health Metrics Network: http://www.who.int/healthmetrics/tools/1HMN_Architecture_for_National_HIS_20080620.pdf. ↵

- Page on What is a Health System. World Bank website. Available at: http://go.worldbank.org/PZSJEFTTZ0. ↵

- Olsen LA, Aisner D, McGinnis JM. The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2007. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53481/. ↵

- World Health Organization. National eHealth Strategy Toolkit. Geneva: World Health Organization and International Telecommunication Union; 2012. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75211/1/9789241548465_eng.pdf ↵

- Figure 2 references Part I, page 8 of the WHO-ITU Toolkit. ↵