16 Emerging Nursing Leadership Issues

Brendalynn Ens; Susan Bazylewski; and Judy Boychuk Duchscher

A leader these days needs to be a host—one who convenes diversity; who convenes all viewpoints in creative processes where our mutual intelligence can come forth.

—Margaret Wheatley

Introduction

Health care in all sectors is changing at a rapid pace. As nursing leadership and nursing management evolve with this change, the need for new leadership approaches, strategies, and ideas to be actioned becomes more evident. This evolution includes two broad critical aspects:

- responsiveness, responsibility, accountability, and engagement of all nurses (regardless of position) within the health care system; and

- proactive and strategic, collaborative actions to be taken by nurse managers and others in formal leadership roles to ensure changing health care priorities are managed.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize rapidly changing approaches to nursing management and leadership within unit-level environments in Saskatchewan, in Canada, and around the world.

- Assess changing care priorities and turbulent issues within our current health system, and approaches to managing them.

- Identify the importance of business acumen skills and concepts as expectations for administrative roles.

- Recognize the importance of, and approaches for, client- and family-centred care and shared decision making as critical concepts for collaborative and effective care management.

- Determine the importance of the manager or leader’s personal journey planning for fruitful and fulfilling career development and professional growth.

- Recognize transition shock.

- Describe the five foundational elements of professional role transition for new nurses.

16.1 Transformational Leadership and Change: The Nursing Management Landscape

The rate of change is not going to slow down anytime soon. If anything, competition in most industries will probably speed up even more in the next few decades.

—John P. Kotter (1995)

An Evolving National and Provincial Landscape

Health care environments have evolved over the years to become highly complex with less predictability; they are constantly undergoing change and restructuring. This has been a result of many factors. The most crucial are changes in the health of populations served and their subsequent health needs paired with available resources and capacity of the health system to meet these needs. Additional factors impacting health care over the past two decades include: increases in the use of technology, a rapidly changing multigenerational workforce, changing requirements of management accountabilities, a greater emphasis on performance measurement, the challenge of managing with scarce resources, rapid growth in inter- and intra-professional teams with changes in scope of practice, and higher consumer expectations. These many factors have influenced and impacted the roles of nurse managers and leaders in ways that have not traditionally been experienced in organizations.

In July of 2011, the Canadian Nurses Association and the Canadian Medical Association published “Principles to Guide Health Care Transformation in Canada.” In response to health care system transformation and restructuring across Canada, this document was developed to provide a common framework to guide regional and jurisdictional change. It identifies the importance of following the five principles of the Canada Health Act and incorporates the Triple Aim Framework from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). The principles in this document are focused around three main themes: (1) enhance the health care experience, (2) improve population health, and (3) improve value for money. These three themes are now a critical focus in nurse managers’ work environments today (CNA & CMA, 2011).

A second document published by the Canadian Nurses Association titled “Registered Nurses: Stepping Up to Transform Health Care” (CNA, 2012) outlines many examples of how registered nurses are putting key principles into action based on the three main themes. Illustrations are provided of the innovative ways in which nurses are improving our health system across Canada today. On a national level, both publications serve as guiding framework documents for nurse managers and leaders in today’s health care environment pointing to new ways of working together across care boundaries to better meet the health needs of the populations we serve.

On a provincial level, Saskatchewan is now beginning a large-scale transformation of its health care system. In December of 2016, a report on system restructuring titled “Optimizing and Integrating Patient-Centered Care” was released by an appointed Advisory Panel of the Saskatchewan government. This panel released 14 recommendations, with a key recommendation focused on consolidating existing health authorities into one provincial authority to “achieve administrative efficiencies and improvements to patient care” (Saskatchewan Advisory Panel, 2016, p. 3).

Two earlier Saskatchewan reports that continue to influence the nursing management landscape in the province today include the “Primary Health Care Framework Report” (Saskatchewan Health, 2012) and the “Patient First Review” (Saskatchewan Health, 2009), both of which identify transformational opportunities for our health care system and nursing management.

Significance for Management and Leadership

These previously mentioned reports emphasize the need for nurse managers and leaders to employ the necessary skills to manage increased complexity in this changing landscape. Managers are required to think beyond the traditional silos and extend their view to focus on the patient journey along a care continuum. As our evolving Canadian health care system places more emphasis on health promotion, primary care, and community-based care, nurse leaders are also being challenged to move from organizations that have had a more controlling and directive style of management to one where engagement, empowerment, and recognition of the unique strengths of all individuals are essential. Because of system transformations, two key areas of change for nurse leaders in our health care system relate to workforce impacts and management system changes.

Workforce Impacts

Despite challenges associated with a changing workforce and increased accountability for scare resources, nurse leaders and managers provide a crucial function in creating healthy work environments. There is growing evidence in the nursing literature about the positive impact of a healthy work environment on staff satisfaction, retention, patient outcomes, and organizational performance (Sherman & Pross, 2010).

A key factor in the changing workforce is the multigenerational makeup of health care organizations today. Our current workforces consist of mixed generations at all levels. Sherman (2006) identifies four generations with distinct attitudes, beliefs, work habits, and expectations, noting that this age diversity will continue for years to come. Spinks and Moore (2007) reported on Canadian generational diversity along with cultural diversity seen at all levels of organizations.

Another major challenge facing nurse leaders today is creating healthy work environments, keeping staff engaged and effectively retained. Mate and Rakover (2016) examined the concept of sustaining improvement in health care, taking into account changes in the Saskatoon Health Region (now part of the Provincial Health Authority) during this time of transformation, emphasizing the critical role of leadership both at the unit level and on the front line. They emphasize that nurse leaders are local champions who must work directly with staff engagement through coaching, team building, daily communicating, and demonstrating the ability to consistently function and manage the new standard processes in order to sustain achievements.

Another workforce impact is the rapidly changing nature of intra- and interprofessional teams. As health systems transform and more attention is paid to the care continuum and the patient and family journey, there is a heightened focus on effective functioning of all teams in touch with the patient and family. Scope of practice changes required to keep up to the changing population needs have led to changes in health care providers’ role on the many teams with whom the patient intersects across the care continuum. The changing nature of teams now requires managers to be attuned to role and scope changes to ensure care is effectively coordinated and integrated during the patient journey.

As early as 1973, in his review of health care in Canada, Robertson recommended the education and deployment of nurse practitioners (NPs) across the health care system, as a way to improve continuity of care and promote efficiency in the system (Stahlke, Rawson, & Pituskin, 2017, p. 488). NPs are “registered nurses who have additional education and nursing experience, which enables them to:

- autonomously diagnose and treat illnesses;

- order and interpret tests;

- prescribe medications; and

- perform procedures.” (Canadian Nurses Association, 2016)

Dorothy Pringle (2007) stated that NPs meet the “needs of patients that are not being adequately met by the healthcare system with its current configuration of roles” (p. 5). Their additional education and advanced skill set support them in providing leadership in health care. The role and performance of NPs has been found to be comparable to physicians across many aspects of care (Stahlke et al., 2017). Their study, referenced in the Research Note below, examines patient perspectives on NP care and further identifies the value of the NP within the health care system.

Research Note

Stahlke, S., Rawson, K., & Pituskin, E. (2017). Patient perspectives on nurse practitioner care in oncology in Canada. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 49(5), 487–495. doi:10.1111/jnu.12313

Purpose

“The purpose of this study was to add to what is known about patient satisfaction with nurse practitioner (NP) care, from the perspective of breast cancer patients who were followed by an NP” (Stahlke et al., 2017, p. 487).

Discussion

Nine patients in an outpatient breast cancer clinic were interviewed about their experiences with NP-led care. These experiences were highly consistent among the patients. Patients were initially surprised that they would receive their ongoing care from a NP. However, as care progressed, several of them were relieved to be assigned to the NP, because those assigned to the doctor were the “sicker” people. They were seen by the NP for almost their entire course of treatment. Patients were comfortable and confident in the NP care; however, they continued to believe that the physician was in charge. The NPs were “described as being more ‘hands-on’ and it was said that ‘they look at the bigger picture . . . dealing more with the individual’ and tapping into the patient’s own strength and resources for healing” (Stahlke et al., 2017, p. 491).

“Despite any initial misgivings or misunderstandings, these patients unanimously felt strongly positive about their NP-led care experiences, explaining that the NP was ‘a bonus’ (P6). That ‘the experience was wonderful’ (P5) and ‘she was just terrific with me’ (P5). One summed up the general sentiment, saying, ‘I’ve just been so fortunate. It was a gift. She’s a gift’ (P9)” (Stahlke et al., p. 491).

Application to practice

Despite the role ambiguity between the physician and NP, the patients valued the leadership of the NP in their care. Patient satisfaction is documented as being closely linked with better patient outcomes (Thrasher & Purc-Stephenson, 2008) and consequently the value of the NP role has become more evident. “NPs hold the potential to transform the patient experience and offer access to excellent, patient-centred care” (Stahlke et al., p. 492).

Figure 16.1.1 Celebration of the Birth of the Saskatchewan Association of Nurse Practitioners

Focusing on Quality Improvement: Management systems changes

Saskatchewan has been engaged in a transformational approach to management systems through a method of provincial strategy-setting “to set priorities, determine goals for the system, establish plans to achieve the agreed-upon goals locally and provincially, and measure progress toward these goals” (Health Quality Council, 2010). These changes have lead to an increased inclusion of nurses in decision making at various levels. As of 2013, all management staff in Saskatchewan received training on the Lean management system, a quality assurance approach. The training contained a consistent management approach for all leaders and managers in the province with standard processes that cascade up and down the management hierarchy. This approach and increased transparency of organizational direction required managers and leaders to develop and sharpen their communication skills, along with their skills for engaging staff and leading change initiatives. A greater emphasis on performance measurement also required managers and leaders to develop new skills for data collection to monitor various aspects of their unit’s performance, to learn how to display data on charts and graphs, and to use this information to tell a story about how the care aligns with and contributes to the overall provincial strategic directions. Inherent in this approach are concrete activities such as visibility walls, daily huddles at all levels of the organizations, and quarterly and annual reviews. As leaders of these activities, nurse managers and local unit leaders are required to engage staff on a daily basis as they communicate overall direction to their staff and work to build engagement in outcomes. These new processes are highly inclusive of all members of the health care team including patients and families.

Overall Impact on Leadership Styles

Chapter 1 of this textbook described various leadership styles. Strengths-based nursing leadership “redirects the focus from deficits, problems and weaknesses to use strengths that include assets and resources to manage problems and overcome and contain weaknesses” (Gottlieb, Gottlieb, & Shamian, 2012, p. 1). This style is also seen to support an environment of intra-professional teams and is a perspective that places the person and family at the centre of care.

Essential Learning Activity 16.1.1

For additional local information on the role and scope of nursing practice, consult the Saskatchewan Registered Nurses’ Association webpage on Nursing Practice Resources.

From the Field

Be able to clearly articulate what the transformed organization will look like to staff by providing concrete information on what you know as a manager, and what you don’t know, and regularly getting up-to-date, reliable information during the change.

Increase communication frequency and methods with staff during transformative change, using a variety of methods and communicating the same message a minimum of seven times.

16.2 Managing Turbulent Times and Responding to Competing Priorities

Chapter 1 of this textbook outlined the necessity for nurse leaders and scholars to study and understand the principles of a complex adaptive system (Pangman & Pangman, 2010). Adding to these principles, nurse leaders need to be knowledgeable and responsive to environmental factors and changes affecting or creating turbulence within their local health care realms.

Turbulence Explained

Turbulence can be viewed as any upheaval or change (sudden or gradual) from normal. In health care, it relates to sudden or continuous times of uncertainty, or irregularities in resources, changing budgets, or adjusted strategic priorities. It involves issues impacted by changing political or administrative leadership, policy, or funding models, and by the evolution of care delivery methods, a refocusing on safety or risk issues, the introduction of new technologies or treatments, or staff attrition and adjustments in a facility. For nurse managers and leaders, it can result in competing priorities and complex decision-making processes.

In health care settings, it may be easiest for the nurse leader to consider turbulence as occurring on two separate levels: (1) broader changes at the high levels (i.e., national policy change or impact; national or provincial demographics or statistics); and (2) focused change at the more grassroots levels (i.e., regional, hospital, or unit). A change at the higher levels inevitably (and eventually) affects the grassroots levels over time.

Turbulence often intersects at the broad (federal) and local (regional) levels of health care. Both levels can have significant direct and indirect impact on local care and decision making for nurse leaders, even if at first glance they appear not to be relevant. Based on need and the span of control, nurse managers may find themselves having to respond promptly by making staffing adjustments, training staff on new skills, purchasing new equipment, decommissioning old or outdated treatments or equipment, re-directing program priorities, changing budget priorities, or even introducing new programs to ensure safety and quality. Decisions during turbulent times need to be thoughtfully and carefully made in a timely way, using the best available research, local data, and consultative sources.

Vigilance about relevant turbulence and knowing who to consult for accurate information and data will assist the nurse leader in being well informed and to anticipate turbulence before it occurs unexpectedly and leads to unanticipated results. Proactive responsiveness will support the development of trust and collaboration with colleagues and staff and ensure seamless transitions of care for clients.

Proactive Responsiveness: Being Well Informed

Being caught off-guard by unexpected turbulence requiring immediate change or a quick decision is never ideal for nurse managers or leaders. Whenever possible, they prefer to avoid having to react quickly and fix a local issue without thoughtful consideration. In order to move from reactive to proactive, nurse leaders and managers should understand both high-level and grassroots issues affecting their local health care environments.

This requires the nurse leader or manager to be well informed and know where to find the best resources. Table 16.2.1 provides credible information on emerging priorities and resources.

|

Priority |

Resources |

|---|---|

|

Changing demographics |

The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report On The State Of Public Health In Canada 2014—Public Health In The Future (The Public Health Agency of Canada) |

|

First Nations health priorities |

An Overview of Aboriginal Health in Canada (National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health) First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (Health Canada) |

|

Emerging drug and device issues |

Consumer Health Products Canada (Health Canada) What’s New— Drug Products (Health Canada new medication approvals) Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Common Drug Review (CDR) Joint Statement of Action to Address the Opioid Crisis (Health Canada) Safe Medical Devices in Canada (Health Canada) |

Domino Effects of Change

The mere introduction of a single new medical treatment, innovation, or health technology (e.g., device) into one department in a health care system can resonate and spread to other departments within that system rapidly. Hospital services that may be affected (directly or indirectly) include housekeeping, information technology/information management, health records, diagnostic imaging, laundry services, and other clinical departments. Unexpected costs, costly software updates, additional staffing, or process or protocol changes may be required to keep up with what is required from a new treatment introduction. For these reasons, it is critical for ongoing, open communication with other departments to occur in advance of any new changes.

A final turbulent adjustment for many health care systems and managers is the shift away from the focus on disease or illness and toward wellness and preventive strategies (PHAC, 2016). Health care leaders encourage funding models that support preventive programs and services, including screening programs. With limited budgets, managing this shift toward preventive approaches can be costly and must be balanced with urgent acute and long-term care service needs for all clients in the health system (CNA, 2012).

From the Field

Tips

- Know and use appropriate and credible online sources to verify facts, statistics, and data.

- Keep abreast of changing demographics both locally and nationally to anticipate change and need for modifications to service.

- Pay attention to local government priorities for funding to support local program development and respond to shifting priorities (e.g., preventive services).

- Communicate planned changes and new ideas effectively to others to ensure you have collaboration and support to move your new ideas forward. Consult with experts and others who may be affected (directly or indirectly) with planned innovations or changes.

- Refer to the SRNA’s “Standards and Foundation Competencies for the Practice of Registered Nurses.”

Essential Learning Activity 16.2.1

1. Imagine you are a nurse manager tasked with purchasing a new large piece of equipment for your department. Physicians and nurses from your unit just heard about it at a trade show in England. They would like you to purchase it as soon as possible to try out with patients here in Saskatchewan.

Review “13 Considerations for Making an Evidence-Informed Decision” on the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health website and consider which factors may be most important for you to assess prior to making a decision.

2. What thoughts do you have about the health of seniors in your community and growing old (in general)?

Make a brief list of what you believe about their seniors’ health, then read the Myths associated with an aging population section of “The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2014—Public Health in the Future” on the Public Health Agency of Canada website. How did you compare?

16.3 Business Acumen and Tangible Skills

Traditionally, the head nurse position within a hospital unit was primarily concerned with managing clinical issues and coordination of care with appropriate staff. These roles are changing rapidly as health care and leadership roles are evolving in nursing. Now more than ever, nurse managers may or may not require clinical expertise to fulfill their duties. Instead, they require practical business skills, tools, and tactics for comprehensively managing departments and ensuring personal career success.

To be successful change agents, managers, and leaders must strive to acquire and use business skills and develop acumen, the ability to make good judgements in an efficient and well-informed way.

Business Skills and Tactics

Table 16.3.1 highlights specific practical business skills and tactics now required for formal nurse leaders and managers to fulfill their roles effectively. Where appropriate, additional online resources and links have been included for further study.

|

Business Skill |

Resources |

|

Understand strategic planning |

|

|

Use statistics and data to prove your point |

https://www.ahrq.gov/research/data/index.html http://www.qp.gov.sk.ca/documents/english/Statutes/Statutes/H0-021.pdf |

|

Critically appraise published research to ensure quality and credibility of supporting data |

Communication at work must reflect an appropriate business writing style befitting professional practice environments. Table 16.3.2 outlines some of the considerations relevant to various methods of communication.

|

Method of Communication |

Factors to Consider |

|

Detailed written report outlining a full plan (multiple pages, including planning processes) |

|

|

Business case or business proposal (maximum 3–4 pages) |

|

|

Outline or business brief |

|

|

Presentation |

|

|

Newsletter or memo |

|

|

|

|

From the Field

- Educate yourself on necessary business acumen.

- Educate yourself and plan ahead, even if the future is unpredictable.

- What you do with your budget impacts others. Coordinate and share your budget plans with other similar departments that could be affected by plans you have for change, quality improvement, and enhancement in services and care.

- Focus on patient outcomes. For example, “If I make X change in care in my unit, it will result in a better care experience for the patient and shorter hospitalization times.”

16.4 Patient and Family Collaboration for Care Delivery

As health systems have moved from a disease-oriented approach toward a model focused more on health prevention, promotion, and wellness, so too has the philosophical foundation of how patients and families are engaged in care. Traditionally, patient and family involvement in care was more visible and more accepted by health care providers in specific clinical areas such as pediatrics, obstetrics, oncology, and palliative care. Now this expectation from consumers is being extended to all sectors of the care continuum. A key transformational shift in the health care landscape over the past two decades has been a focus on the concept of patient– and family–centred care (PFCC) also known as person–centred care (according to the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer), or client– and family–centred care (CFCC) (by Accreditation Canada). These definitions are now widely used to define the inclusiveness and collaboration with patients and families in determining their care and outcomes at all touch points of the care continuum. For purposes of this section of this chapter, the terms patient, client, and resident will be used interchangeably.

Definitions

The Institute of Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC, 2017) defines PFCC as “an approach to the planning, delivery, and evaluation of health care that is grounded in mutually beneficial partnerships among health care providers, patients, and families.” The four key concepts espoused by the IPFCC and followed within Canada and Saskatchewan are:

Dignity and respect. Health care practitioners listen to and honor patient and family perspectives and choices. Patient and family knowledge, values, beliefs, and cultural backgrounds are incorporated into the planning and delivery of care.

Information sharing. Health care practitioners communicate and share complete and unbiased information with patients and families in ways that are affirming and useful. Patients and families receive timely, complete, and accurate information to effectively participate in decision making.

Participation. Patients and families are encouraged and supported in participating in care and decision making at the level they choose.

Collaboration. Patients, families, health care practitioners, and health care leaders collaborate in policy and program development, implementation, and evaluation, in research, in facility design, and in professional education, as well as in the delivery of care.

Essential Learning Activity 16.4.1

For a historical perspective on the evolution of PFCC, see “Partnering with Patients and Families To Design a Patient- and Family-Centered Health Care System: A Roadmap for the Future,” published by the IPFCC.

The IPFCC’s definition is aligned with that of Accreditation Canada, which defines client and family centred care (CFCC) as “an approach that fosters respectful, compassionate, culturally appropriate, and competent care that responds to the needs, values, beliefs, and preferences of clients and their family members” (2015). In CFCC, the word client also means patients and residents. At the heart of PFCC is the concept of working “with” the patient instead of doing “to” or “for.” This key concept puts the client and family at the centre of the care as opposed to a model where the provider’s perspective is dominant, so the health care provider and the client have a true partnership.

Putting Patients First

In 2009, Saskatchewan released its “Patient First Report,” which started Saskatchewan on a focused transformational journey to embed PFCC/CFCC into the culture of health care in the province. The key recommendation from this report stated:

That the health system make patient- and family-centred care the foundation principal aim of the Saskatchewan health system, through a broad policy framework to be adopted system wide. Developed in collaboration with patients, families, providers and health system leaders, this policy framework should serve as an overarching guide for health care organizations, professional groups and others to make the Patient First philosophy a reality in all workplaces. (Saskatchewan Health, 2009, p. 8)

Saskatchewan is now actively engaged in strategic efforts to advance patient- and family-centred care in this province and has set targets and measures to achieve this culture change.

Essential Learning Activity 16.4.2

For more information on specific targets and goals of quality health work in Saskatchewan health care, please review the following websites and documents:

The Saskatchewan Patient- and Family-Centred Care Guiding Coalition’s newsletter (Fall 2016), Putting Patients First.

Saskatchewan Health Quality Council’s report, “Shared decision making: Helping the system and patients make quality health care decisions.”

Changing Effects of Patient- and Family-Centred Care

This new collaborative approach to care delivery has a major impact on how health care providers engage with patients and families in our system, and the subsequent involvement and influence of the nurse manager or leader. One specific area that managers and leaders must pay attention to is related to the changing expectations of clients and their family members who have increased access to information through technology. This includes expectations for information flow between care providers and increased expectations around shared decision making and meaningful engagement. One of the key tenets of PFCC is “every patient, every time.” This culture change involves all levels of health care providers from care providers to support service staff.

Essential Learning Activity 16.4.3

For more information on the changing effects of patient- and family-centered care, see the patient engagement resource hub on the website of the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement.

Review the following websites and consider how their information impacts local management environments:

Institute for Patient- and Family-Centred Care, Free Downloads—Reports/Roadmaps

For more information on innovations in advancing patient- and family-centered care in hospitals, see the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s web page Advancing the Practice of Patient- and Family-Centered Care in Hospitals.

From the Field

- Gain increased knowledge in PFCC as a sound foundation for a leadership role.

- Increase knowledge on specific examples of successful ways that patients and families have collaborated for their care, and work with patients and families to implement change in your work area (e.g., including patients and families during hospital rounds, changing meal times in long-term care to accommodate resident preferences).

- Enhance communication skills for collaboration and engagement with patients and families as individuals and in groups, such as patient councils. Learn the difference in stakeholder roles, in terms of which are input and consultation and which are decision making, and be able to articulate this to patients and family members.

- Develop communication skills to engage patients and families in participating in and improving care. See examples outlined in the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario’s clinical best practice guidelines (2015) for person- and family-centred care.

- Develop skills in coaching and mentoring diverse groups of staff, patients, and family members. Develop skill in conflict resolution for helping staff handle challenging patient or family issues.

- Be alert to current issues that will impact an increased emphasis on patient and family engagement in care, such as medical assistance in dying and advanced care directives.

- Learn how to educate and direct patients and families to credible resources, particularly on the internet.

- Learn communication processes for appropriate disclosure of errors in an effective manner and include patients as part of quality improvement.

- Ensure that you and your staff understand how to maintain patient privacy and confidentiality with increased family involvement.

- Sharpen skills in measuring patient experience. For example, develop mechanisms to hear routine feedback from patients and families and use this to improve care.

16.5 Managing Stress and Self-Care Practices

Today’s nurse manager roles are diverse and constantly changing. Multiple priorities and complex pressures affect nearly every aspect of a manager’s day-to-day activities. Urgent and non-urgent considerations often intersect and can negatively impact the time and resources available for efficient, optimal decision making. In some instances, ambiguity and missing data can complicate decision-making processes. Priorities are sometimes set and then re-adjusted based on time-sensitive data, higher-level turbulent issues, or patient care management needs. Leading and managing in this environment is the new health care norm.

Within this chaos and non-stop change, it is critical for the nurse manager or leader to keep top of mind their primary leadership responsibility to organizations and their staff and to ensure proactive and positive oversight and safe, appropriate quality care for patients. Managers need to expect and anticipate change and be able to communicate effectively and collaborate easily with others to move health care forward. The use of complexity theory to explain and provide a framework for the ever-changing environmental priorities was discussed in Chapters 1 and 3.

There is no one best way to manage change in an organization. Pragmatic and logical thinking must be at the forefront of every consideration. Proactively supporting and promoting change is both a demanding and fatiguing task. Without careful consideration of internal strengths, self-awareness, and resilience coping mechanisms, it is easy for nurse leaders to experience negative impacts on their lives and behaviours. Sometimes the deleterious effects such as fatigue may not be realized, but may eventually lead to burnout, which may be displayed as emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and personal inefficacy (Laschinger & Fida, 2014).

Now more than ever, self-care is essential for managers and leaders as a proactive and continuing activity. Self-care always begins with strategic awareness of strengths, skills, and abilities that you as a manager or leader possess. It has been said that the best leaders do not rely on their positional power, but rather focus on their best attributes and assets to enhance and succeed at their roles (Rath & Conchie, 2009). Similarly, Gottlieb et al. (2012) discussed strengths-based leadership as a multifaceted concept involving the development of not just tangible knowledge and skills but also of an un-anxious mindset that allows individuals to utilize their best developed strengths for problem management, while focusing on development of weaker skills over time. Their theory of strengths-based leadership extends beyond self-assessment to further recognize strengths in others on a team and among those we collaborate with. Additionally, evidence related to how you as a leader think and view the world also impacts your actions and behaviours. Mindfulness and mindset of the manager are critical in navigating this complexity, as discussed in previous chapters.

Connecting to a leadership framework assists in focusing the personal growth of managers. Closely tied to the work of Rath and Conchie (2009) is the management framework of LEADS in a Caring Environment, now supported and endorsed by the Canadian College of Health Leaders. LEADS correlates to: Leading self, Engaging others, Achieving results, Developing coalitions, and transforming Systems.

Leading self as the first step in the LEADS framework highlights how essential it is for a manager or leader to consciously embark on a personal journey of self-awareness, introspection, and recognition of their skills, intuitive character strengths, and expertise. It is not an expectation for managers or leaders to be good at everything, but a strategic plan for self-care and personal journey development can begin if they are first aware of their strengths as well as weaker areas to work on.

From the Field

- Consult and complete the leadership and management competency assessment tools from the following two documents to recognize areas of management or leadership strengths, as well as those that may need attention: SRNA’s Standards and Foundation Competencies for the Practice of Registered Nurses and CNA’s Canadian Nurse Practitioner Core Competency Framework.

- Consider approaches to using emotional intelligence for decision making and for engaging others effectively (Bradberry & Greaves, 2009), and consider your strengths as part of your strengths-based leadership approach (Gottleib et al., 2012).

- Use the results of competency assessment tools to help you set goals for career and professional development learning. Stick to these goals and evaluate them regularly (Echevarria, Patterson, & Krouse, 2017).

- Be aware of physical and mental cues from your body that you may be becoming overwhelmed or need a “time-out” from complex and fast-paced environments. Negotiating for time to ponder and strategically consider options almost always leads to more successful decision making.

- Take care of your personal health by practising healthy lifestyle habits; specifically, pay attention to adequate sleep, healthy eating, exercise, and stress management activities.

- Identify a mentor—someone in a similar or higher management or leadership position who you look up to and aspire to emulate. Consult with your mentor and coordinate a relationship for feedback, advice, and support to guide your personal growth as a manager or leader over time.

- Practise good time management and resource management skills to support efficiencies and streamlined processes. Self-motivation skills and cues are important to ensure you keep on task and that you meet deadlines for reports or commitments.

- Schedule protected time in your work schedule to periodically review your strengths and approaches. Think outside the box in terms of creativity and ways to enhance your personal growth.

16.6 International Nursing Leadership

This chapter has explored critical emerging leadership issues in nursing with a focus on the Canadian, and specifically the Saskatchewan, context. Now it is time to look at nursing around the world. In the following activity, spend time with Dr. Judith Shamian, President of the International Council of Nurses (2013–2017), as she discusses global health and nursing as part of the Global Leadership Series hosted by the Sick Kids Centre for Global Child Health.

Essential Learning Activity 16.6.1

Watch this video “Sustainable Development Goals: Global Health and Nursing” (56:10), which is part of the Global Leadership Series hosted by the Centre for Global Child Health. In this video, Dr. Judith Shamian discusses global nursing and sustainable development goals. Then answer the following questions:

- How is the Canadian Nurses Association (CNA) linked to the International Council of Nurses (ICN)?

- Why does Dr. Shamian state that money spent on health care workers is an investment?

- What are the three “buzzwords” that Dr. Shamian mentions?

- Identify the sustainable development goals (SDGs) for the world.

- How can you, as a nurse leader, work to assist citizens of the world to achieve these goals?

16.7 Foundational Elements of Professional Role Transition for New Nurses

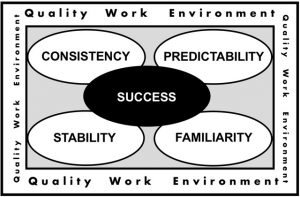

There are foundational intersecting elements that feed into the new graduate nurse’s (NGN) initial experience in the workplace: (1) stability, (2) predictability, (3) familiarity, (4) consistency, and (5) success (Duchscher, 2012). When all is in order, these elements put us in the driver’s seat of our own experience.

Figure 16.7.1 Quality Workplace Factors for New Nursing Graduates

Stability refers to how steady the circumstances and situation are for you during your transition experience; essentially, stability refers to that which is unlikely to change or deteriorate. Stability is a fundamental feature of homeostasis, which even from a purely bio-physiologic perspective is something all humans seek. When you think about optimizing stability remember to think personally as well as professionally. Try to consider work that provides you with clinical situations that are stable, in a context that doesn’t constantly change. For this reason, floating (or being on a team that goes from unit to unit on a daily basis) does not provide for stability of patient population. Further to this, contexts where a patient’s clinical presentation is highly dynamic, or whose level of illness is such that there is a near certain likelihood of instability or decompensation (i.e., emergency or critical care), are precarious for the NGNs growing knowledge base. The immature pattern recognition capacity of the new practitioner renders the NGNs response to this kind of clinical volatility challenging. Finally, if you feel like your home life is unstable (i.e., things feel chaotic or stressful at home), the stability of your workplace is even more important. The reverse is also true: a stable home life is critical if you lack stability in the workplace.

Predictability for NGNs relates to their ability to know: (1) WHAT they will do (e.g., What level of performance is expected of me now that I am a graduate nurse? What do I need to do in this role? Am I comfortable enough with those in charge to tell them when I am in over my head?); (2) WHERE they will do it (Where am I working? Am I going to the same workplace every shift or floating to multiple units? If I have to start as a casual employee, how can I get enough hours without exposing myself to too many unfamiliar workplaces?); (3) WHEN they will do it (Am I working 8-hour or 12-hour shifts? What is the rotation? When X happens [a code, a death, a distraught patient, a diagnosis of a sexually transmitted infection, a suicide in the community], how do I respond?); (4) WHO will they do it with (Who will I be working with? Who do I go to if I have questions? Who can fire me? Who can I trust?); and (5) HOW they will do it (What are the differences between what I did as a student and what is expected of me now as a graduate nurse? What will I do if I come up against something I have never done before? Are things done differently here relative to where I practised as a student?).

Familiarity speaks to the saying, “I’ve seen this before,” and perhaps even “…and I know what to do about it.” If you were privileged to be employed as a senior student or spend your final practicum (or capstone or consolidated learning experience) on the unit or in the practice context where you intend to work as a graduate nurse, the lack of familiarity may not contribute as much to your transition stress. Even knowing where to get what you need to do your work is a relief of transition stress (e.g., where the STD kits are in the clinic or where the special bags of N/S with 20meqK+/L are located on the unit).

Knowing who’s who in the practice area is very helpful. While many NGNs experience phenomenal collegiality with their senior counterparts, there are equal numbers who are quickly introduced to, or warned about, those individuals to avoid because they “eat their young.” A new workplace is a bit like a minefield—you obviously need to keep moving but no one tells you where the mines are planted (sometimes even they don’t know) and not all mines have obvious triggers that you can see before they explode. It is in the area of familiarity that nursing residency/internship programs (also sometimes called a graduate nurse program or a transition facilitation program) or less formal supernumerary staffing arrangements have significant impact on a transition experience. Supernumerary staffing means that you work with patients and your colleagues without being given an actual assignment. The advantage of this is that you can move around your new environment, taking advantage of various learning experiences, getting to know your colleagues and the patient demographic without the stress of predetermined workload expectations. Mentorship or preceptorship programs constitute another approach to familiarizing you with your roles and responsibilities as a new nurse. The concept of mentor usually encompasses a longer-term, more personally professional relationship between a novice and experienced nurse. Conversely, the role of preceptor is often associated with the transferring of skill knowledge and therefore is often used in the context of a pairing between a nursing student and a senior nursing guide. Having said that, preceptors can also be expert clinical nurses who are buddied with a new nurse for the purposes of teaching them about the roles, routines, and responsibilities related to their new workplace. Along those lines, it is thought that we can be assigned a preceptor, but that a mentor is someone we choose, as this relationship requires a more personal connection between mentor and mentee.

Consistency is the experience of being exposed to a similarly presenting event, situation, concept, or idea, which affords you a level of familiarity and predictability. From a purely logical perspective, consistency is defined as that which does not contain contradictions. Here are some of the inconsistencies to watch for as you enter professional practice:

- The practice environment is more often than not constructed to ensure efficiency and productivity over effectiveness and quality.

- Health care institutions must function within budgets that are influenced by many competing sociopolitical and economic factors. This means that there will often be tension between the ethics-based, value-driven motivations of health care providers and the fiscal and human resource limitations of the health care system.

- When you graduate from an educational program that encourages independent critical thinking, it is a bit disconcerting to find yourself relatively dependent on the experienced nurses around you. You may feel a sense that you should be independent—you think others are expecting you to perform independently and this is what you often expect of yourself. Confusion reigns when you quickly come to realize that so much of what you are doing and seeing is new. The inconsistency is between what you think people expect of you, what you expected of yourself as a student, and the recognition of your own limitations as a new practitioner.

When experiencing inconsistencies, remember to stay grounded in the fundamental objectives of a NGN:

- Gain a sense of the roles and responsibilities of a graduate nurse.

- Create a workload organizational system that works for you.

- Learn how to manage your time within a gradually increased workload complexity.

- Learn the routines of your workplace.

- See and experience a variety of “normal” and “abnormal” situations under controlled conditions.

- Debrief with a trusted experienced colleague, nursing educator, or mentor about clinical situations to gain a depth of understanding of clinical patterns and the relationships between those patterns and the judgements that arise out of them.

- Gain confidence in performing the fundamental skills required of a nurse in the setting where you work. (The skills of an expert nurse are not simply tasks, but a complex and layered portfolio of roles and responsibilities enacted in an infinitely varied set of sequences and combinations and under dynamic, fluid and often intense and risk-laden conditions.)

- Assess patients of increasing complexity at varying levels of stability.

- Learn how to work on a team—and learn about your team.

- Get to know the dynamics of your workplace. What is “nursing” to your colleagues and how is nursing valued within your institution and community?

- Pursue a balance between your personal life and professional life.

- Learn who you are (again) now that you are not consumed by studying and academic deadlines.

- Have fun again!

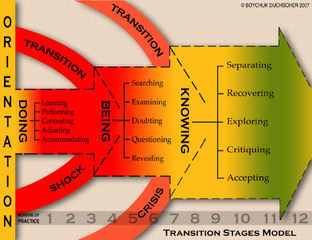

Essential Learning Activity 16.7.1

Watch the video “Duchscher’s New Graduate Nurse Transition Stages” (19:53) by Dr. Judy Boychuk Duchscher who discusses new graduate nurse transition stages. Refer also to the following Figures 16.7.2 and 16.7.3. More information on new graduate nurse transition can be found on the Nursing the Future website. Answer the following questions:

- Describe the stages of transition. What recommendations does Dr. Duchscher give for each stage?

- Where do the majority of new nurses usually find employment? Why?

- What is flow? Give an example of flow.

- What is the difference between accommodating and adjusting?

Figure 16.7.2 Transition Stages Model

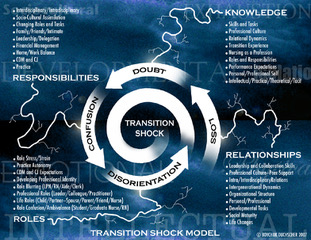

Figure 16.7.3 Transition Shock Model

Enlarge image: Dec10 Transition Shock Model

Summary

Given the multiple challenges and uncertainty now and into the future, it is imperative for nurse managers and leaders to continue to enhance their leadership effectiveness. Carroll (2006) describes several effective ways to become a nurse leader, regardless of your current training or position. Among these, the following relate directly to nursing management and the journey toward career success:

- Make a commitment to lifelong learning through a self-development plan.

- Find your passion and begin to build and develop your strengths in this area.

- Get involved in the nursing community and keep abreast of changing issues affecting nursing.

- Understand your personal leadership style and how it impacts your work.

After completing this chapter, you should now be able to:

- Recognize rapidly changing approaches to nursing management and leadership within unit-level environments in Saskatchewan, in Canada, and around the world.

- Assess changing care priorities and turbulent issues within our current health system, and approaches to managing them.

- Identify the importance of business acumen skills and concepts as expectations for administrative roles.

- Recognize the importance of, and approaches for, client- and family-centred care and shared decision making as critical concepts for collaborative and effective care management.

- Propose the importance of the manager or leader’s personal journey planning for fruitful and fulfilling career development and professional growth.

- Recognize transition shock.

- Describe the five foundational elements of professional role transition for new nurses.

Figure 16.7.4 Letter from Katherine McKenzie Ross to All New Nursing Graduates

Exercises

- Select a manager you know from one of your clinical sites. Interview this manager to gain insights into the nursing management. Consider asking the following questions: Why did you become a manager? How would you describe your management style? What turbulent changes have you seen in the health system in the past two to five years? How have you adapted to this changing management landscape?

- What are the key findings of the “Optimizing and Integrating Patient-Centred Care” 2016 report? How do you think these findings will impact managers and leaders in Saskatchewan?

- What are three key considerations for nurse managers when assisting with the implementation of an electronic health records system in a nursing unit?

- Review the current age of the patient population in a clinical setting you are or have been in. What are the key health challenges that each age group faces and how are they reflected in your chosen setting? What are you going to do to maximize this engagement in care for this patient group?

- Assess the current activities underway in each of your clinical settings to promote PFCC.

- Consider the rapidly changing and emerging uses of wireless devices and the internet in everyday patient care. Do you think that wireless applications in health care settings improve the efficiency of care delivery systems? Why or why not? How could we measure return-on-investment for these wireless delivery systems over the long term?

- Reflect on your own career path in nursing. What content in this chapter will be useful to you regardless of the type of leader you become in nursing (e.g., bedside, unit leader, manager, director)?

- Looking back to the Global Leadership Series video by Dr. Shamian, how will you find a “spot at the table”? What is your ten-year plan?

References

Accreditation Canada. (2015). Client Family Centred Care. Retrieved from https://accreditation.ca/patients-families/

Bradberry, T. & Greaves, J. (2009). Emotional Intelligence 2.0. San Diego, CA: TalentSmart.

Canadian Nurses Association [CNA]. (2016). Nurse practitioners. Retrieved from https://www.cna-aiic.ca/professional-development/advanced-nursing-practice/nurse-practitioners

Canadian Nurses Association [CNA]. (2012). Primary health care [Position statement]. Retrieved from https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/primary-health-care-position-statement.pdf?la=en

Canadian Nurses Association and Canadian Medical Association. (2011). Principles to guide health care transformation in Canada. Retrieved from https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/files/en/guiding_principles_hc_e.pdf

Carroll, P. (2006). Nursing leadership and management: A practical guide. Clifton Park, NJ: Thomson Delmar Learning.

Duchscher, J. E. B. (2012). From Surviving to Thriving: Navigating the First Year of Professional Nursing Practice (2nd ed.). Calgary, AB: Nursing the Future.

Duchscher, J. E. B. (2009). Transition shock: The initial stage of role adaptation for newly-graduated Registered Nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(5), 1103–13.

Duchscher, J. E. B. (2008). A process of becoming: The stages of new nursing graduate professional role transition. Journal of Continuing Nursing Education, 39(10), 441–450.

Echevarria, I. M., Patterson, B. J., & Krouse, A. (2016). Predictors of transformational leadership of nurse managers. Journal of Nursing Management, 25(3), 167–175. doi:10.1111/jonm.12452

Gottleib, L., Gottleib, B., & Shamian, J. (2012). Principles of strengths-based nursing leadership for strengths-based nursing care: A new paradigm for nursing and healthcare for the 21st century. Nursing Leadership, 25(2), 38–50. doi:10.12927/cjnl.2012.22960

Health Quality Council, Saskatchewan. (2010). Shared decision making: Helping the system and patients make quality health care decision. Retrieved from http://hqc.sk.ca/Portals/0/documents/Shared_Decision_Making_Report_April_08_2010.pdf

Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care [IPFCC]. (2017). Advancing the practice of patient– and family–centered care in hospitals. Retrieved from http://www.ipfcc.org/resources/getting_started.pdf

Kotter, J. P. (1995). Leading change: Why transformational efforts fail. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from http://www.gsbcolorado.org/uploads/general/PreSessionReadingLeadingChange-John_Kotter.pdf

Laschinger, H. K., & Fida, R. (2014). New nurses’ burnout and workplace wellbeing: The influence of authentic leadership and psychological capital. Burnout Research, 1(1), 19–28. doi:10.1016/j.burn.2014.03.002

Mate, K., & Rakover, J. (2016). Four steps to sustaining improvement in health care. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2016/11/4-steps-to-sustaining-improvement-in-health-care

Pangman, V. C., & Pangman, C. H. (2010). Nursing leadership from a Canadian perspective. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Pringle, D. (2007). From the editor-in-chief. Nurse practitioner role: Nursing needs it. Nursing Leadership (1910-622X), 20(2), 1–5. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=109846474&site=ehost-live

Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC]. (2016). Health status of Canadians, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/healthy-canadians/migration/publications/department-ministere/state-public-health-status-2016-etat-sante-publique-statut/alt/pdf-eng.pdf

Rath, T., & Conchie, B. (2008). Strengths-based leadership. New York: Gallup Press.

Saskatchewan Advisory Panel on Health System Restructure. (2016). Optimizing and integrating patient care. Retrieved from http://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/3251960/Saskatchewan-Advisory-Panel-on-Health-System.pdf

Saskatchewan Health. (2012). Patient centred, community designed, team delivered: A framework for achieving a high performing primary health care system in Saskatchewan. Retrieved from http://publications.gov.sk.ca/documents/13/81547-primary-care-framework.pdf

Saskatchewan Health. (2009). Forpatients’ sake:Patient First Review Commissioner’s Report to the Saskatchewan Minister of Health. Retrieved from https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/health-care-administration-and-provider-resources/saskatchewan-health-initiatives/patient-first-review

Sherman, R. (2006). Leading a multigenerational nursing workforce: Issues, challenges and strategies. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 11(2), manuscript 2. doi:10.3912/OJIN.Vol11No02Man02

Sherman, R., & Pross, E. (2010). Growing future nurse leaders to build and sustain healthy work environments at the unit level. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 15(1), manuscript 1. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol15No01Man01

Spinks, N., & Moore, C. (2007). The changing workforce, workplace and nature of work: Implications for health human resource management. Nursing Leadership, 20(3), 26–41. doi:10.12927/cjnl.2007.19286

Stahlke, S., Rawson, K., & Pituskin, E. (2017). Patient perspectives on nurse practitioner care in oncology in Canada. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 49(5), 487–495. doi:10.1111/jnu.12313

Thrasher, C., & Purc-Stephenson, R. (2008). Patient satisfaction with nurse practitioner care in emergency departments in Canada. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 20(5), 231–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00312.x

Wheatley, M. “35 Magnificent Margaret J. Wheatley Quotes,” BrandonGaille.com (blog) Retrieved from http://brandongaille.com/35-magnificent-margaret-j-wheatley-quotes/