9 Common Change Theories and Application to Different Nursing Situations

Sonia A. Udod and Joan Wagner

Leaders take us to places we’ve never been before. But there are no freeways to the future, no paved highways to unknown, unexplored destinations. There’s only wilderness. To step into the unknown, begin with the exploration of the inner territory. We continue to discover that the most critical knowledge for all of us—and for leaders especially—turns out to be self-knowledge. (Kouzes & Posner, 2007, p. 346)

Introduction

Change is an essential component of nursing practice. Leading change is a challenge for nurse leaders amid the complexities and challenges of evolving health care environments in providing quality patient care. This chapter is designed to provide nurse leaders with guidance through various theories and frameworks to effectively support the change process in shaping healthy work environments. Additionally, you will learn about resistance to change and how to respond constructively to change. This chapter focuses on providing guidelines for nurse leaders on behaviours and practices for encouraging and facilitating change in the health care setting.

Learning Objectives

- Explain why nurses have the opportunity to be change agents.

- Identify how different theorists explain change.

- Discuss how the nursing process is similar to the change process.

- Discuss the medicine wheel as a change model.

- Describe the nurse leader’s role in implementing change and the call to action.

- Differentiate among change strategies.

- Recognize how to handle resistance to change.

The rapid pace of change in Canada’s health care system provides opportunities for nurse leaders to refine and advance their leadership and management skills for advancing change. Various forces that drive change in health care include rising costs of treatment, new technologies, advances in science, workforce shortages, and an aging population. Change initiatives must always be implemented for good reason within the context of advancing institutional goals and objectives. Balancing change is a key challenge within a patient- and family-centred model to provide safe and reliable patient care (Stefancyk, Hancock, & Meadows, 2013; Saskatchewan Ministry of Health, 2011).

9.1 The Nurse Leader as Change Agent

Nurse leaders must ensure the day-to-day operation of their unit(s) in a rapidly evolving health care system. Nurse leaders are often called upon to be agents of change and are often responsible for the success of a project. Yet the literature suggests that leaders continue to struggle with change despite the frequency with which they are involved in leading change (Gilley, Gilley, & McMillan, 2009; Quinn, 2004). A change agent is an individual who has formal or informal legitimate power and whose purpose is to direct and guide change (Sullivan, 2012). This person identifies a vision and rationale for the change and is a role model for nurses and other health care personnel.

Nurse leaders’ behaviours influence staff actions that contribute to change (Drucker, 1999; Yukl, 2013). The significant number of changes that nurse leaders face require new ways of thinking about leading change and adapting to new ways of working. Moreover, leaders work closely with frontline care providers to identify necessary change in the workplace that would improve work processes and patient care. As such, nurse leaders must have the requisite skills for influencing human behaviour, including supervisory ability, intelligence, the need for achievement, decisiveness, and persistence to guide the process (Gilley et al., 2009). Effective change management requires the leader to be knowledgeable about the process, tools, and techniques required to improve outcomes (Shirey, 2013).

9.2 Theories and Models of Change Theories

Knowledge of the science of change theory is critical to altering organizational systems. Being conversant with various change theories can provide a framework for implementing, managing, and evaluating change within the context of human behaviour. Change theories can be linear or non-linear; however, even linear theories do not unfold in a systematic and organized pattern. In the following section, we identify the role of leader and the typical pattern of events that occur in a change event.

Force Field Model and The Unfreezing-Change-Refreezing Model

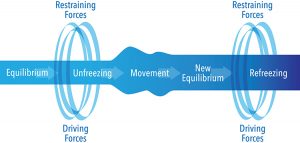

Kurt Lewin (1951) is known as a pioneer in the study of group dynamics and organizational development. He theorized a three-stage model of change (unfreezing-change-refreezing model) in order to identify and examine the factors and forces that influence a situation. The theory requires leaders to reject prior knowledge and replace it with new information. It is based on the idea that if one can identify and determine the potency of forces, then it is possible to know the forces that need to be diminished or strengthened to bring about change (Burnes, 2004).

Lewin describes behaviour as “a dynamic balance of forces working in opposing directions” (cited in Shirey, 2013, p.1). The force field model is best applied to stable environments and he makes note of two types of forces: driving forces and restraining forces. Driving forces are those that push in a direction that causes the change to occur or that facilitate the change because they push a person in a desired direction. Restraining forces are those that counter the driving force and hinder the change because they push a person away from a desired direction. Finally, change can occur if the driving forces override or weaken the restraining forces.

This important force field model forms the foundation of Lewin’s three-stage theory on change (1951) (see Figure 9.2.1). Unfreezing is the first stage, which involves the process of finding a method to assist individuals in letting go of an old pattern of behaviour and facilitating individuals in overcoming resistance and group conformity (Kritsonis, 2005). In this stage, disequilibrium occurs to disrupt the system, making it possible to identify the driving forces for the change and the likely restraining forces against it. A successful change ultimately involves strengthening the driving forces and weakening the restraining forces (Shirey, 2013). This can be achieved by the use of three methods: (1) increase the driving forces that direct the behaviour away from the existing situation or equilibrium; (2) decrease the restraining forces that negatively affect the movement away from the current equilibrium; or (3) combine the first two methods.

The second stage, moving or change, involves the process of a change in thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviours. Lewin (1951) describes three actions that can assist in movement: (1) persuading others that the status quo is not beneficial and encouraging others to view a problem with a fresh perspective; (2) working with others to find new, relevant information that can help effect the desired change; and (3) connecting with powerful leaders who also support the change (Kristonis, 2005). This second stage is often the most difficult due to the fact that there is a level of uncertainty and fear associated with change (Shirey, 2013). Therefore, it is important to have a supportive team and clear communication in order to achieve the desired change.

Lastly, stage three, which Lewin called refreezing, involves establishing the change as a new habit. The third stage is necessary to ensure that the change implemented (in the second stage) will “stick” over time (Kristonis, 2005). Success at this stage will create a new equilibrium state known to be the new norm or higher level of performance expectation (Shirey, 2013).

Although Lewin’s model on change is well known and widely accepted in health care settings, it is often criticized for being too simplistic and linear. Change is often unpredictable and complex, and an effective leader must be aware of many change models.

Figure 9.2.1 The Steps of the Unfreezing-Change-Refreezing Model

9.3 Planned Change

Lippitt, Watson, and Westley (1958) focus more on the role and responsibility of the change agent than on the process of the change itself. Their theory expands Lewin’s model of change into a seven-step process and emphasizes the participation of those affected by the change during the planning steps (Kritsonis, 2005; Lippitt et al., 1958). The seven steps of the planned change model include: (1) diagnosing the problem; (2) assessing the motivation and capacity for change in the system; (3) assessing the resources and motivation of the change agent; (4) establishing change objectives and strategies; (5) determining the role of the change agent; (6) maintaining the change; and (7) gradually terminating the helping relationship as the change becomes part of the organizational culture (see Table 9.3.1).

The steps in this model place emphasis on those affected by the change, with a focus on communication skills, rapport building, problem-solving strategies, and establishing mechanisms for feedback (Kritsonis, 2005; Lehman, 2008).

Phases of Change

Ronald Havelock (1973) also modified Lewin’s model of change to include six phases of change from planning to monitoring (see Table 9.3.1). It is believed that Havelock further developed the unfreezing-change-refreezing model to address two social forces that were gaining momentum in society at the time: “the explosion of scientific knowledge, and the increasing expectation by policy-makers, governments, business and society that scientific knowledge should be useful to society” (Estabrooks, Thompson, Lovely, & Hofmeyer, 2006, pp. 29–30). Havelock argued that adapting Lewin’s change model to include knowledge building, which focused on a systematic integration of theories rather than disjointed approaches, would respond more effectively to real-life situations in managing change (Estabrooks et al., 2006).

The six phases of Havelock’s model are as follows:

- Building a relationship. Havelock regarded the first step as a stage of “pre-contemplation” where a need for change in the system is determined.

- Diagnosing the problem. During this contemplation phase, the change agent must decide whether or not change is needed or desired. On occasion, the change process can end because the change agent decides that change is either not needed or not worth the effort.

- Acquire resources for change. At this step, the need for change is understood and the process of developing solutions begins as the change agent gathers as much information as possible relevant to the situation that requires change.

- Selecting a pathway for the solution. A pathway of change is selected from available options and then implemented.

- Establish and accept change. Individuals and organizations are often resistant to change, so careful attention must be given to making sure that the change becomes part of new routine behaviour. Effective communication strategies, staff response strategies, education, and support systems must be included during implementation.

- Maintenance and separation. The change agent should monitor the affected system to ensure the change is successfully stabilized and maintained. Once the change has become the new normal, the change agent can separate from the change event. (Tyson, 2010)

Innovation Diffusion Theory

Rogers’ five-step theory explains how an individual proceeds from having knowledge of an innovation to confirming the decision to adopt or reject the idea (see Figure 9.3.1) (Kritsonis, 2005; Wonglimpiyarat & Yuberk, 2005). A distinguishing feature of Rogers’ theory is that even if a change agent is unsuccessful in achieving the desired change, that change could be resurrected at a later, more opportune time or in a more appropriate form (Kritsonis, 2005). Roger also emphasizes the importance of including key people (i.e., policy-makers) interested in making the innovation happen, capitalizing on group strengths, and managing factors that impede the process. The five stages to Rogers’ theory are as follows:

- Knowledge. The individual is first exposed to an innovation but lacks information about the innovation.

- Persuasion. The individual is interested in the innovation and actively seeks related information and details.

- Decision. The individual considers change and weighs the advantages and disadvantages of implementing the innovation.

- Implementation. The individual implements the innovation and adjusts the innovation to the situation. During this stage the individual also determines the usefulness of the innovation and may search for further information about it.

- Confirmation. The individual finalizes the decision to continue using the innovation. (Rogers, 1995)

Essential Learning Activity 9.3.1

Watch the video “Lewin’s 3-Stage Model of Change: Unfreezing, Changing & Refreezing” (8:06) by Education-Portal.com for more about Lewin’s change model.

Watch the video “Rogers Diffusion of Innovation” (3:15) by Kendal Pho, Yuri Dorovskikh, and Natalia Lara (Digital Pixels) for more about Rogers’ theory of innovation.

Figure 9.3.1 The Five Steps of the Innovation Decision Process

Rogers’ innovation diffusion theory explains how, why, and at what rate new ideas are taken up by individuals. Rogers defines five-categories of innovation adopters. Innovators are willing to take risks; they are enthusiastic and thrive on change. They play a key role in the diffusion of innovation by introducing new ideas from the external system (Rogers, 1995). Early adopters are described as being more discreet in adoption choices than innovators. They are cautious in their adoption of change. The early majority are those people who take a significantly longer time to adopt an innovation as compared to the innovators and early adopters. The late majority comprise individuals who have a high degree of skepticism when it comes to adopting a change. Finally, the laggards are those who are last to adopt a change or innovation. They typically have an aversion to change and tend to be focused on traditions and avoid trends (Rogers, 1995).

9.4 Non-linear Change Models

Most organizations have viewed change as sequential and linear occurring in a step-by-step fashion. However, nursing has begun to explore non-linear models as a way of guiding more unpredictable change, as these models do not follow an orderly and predictable pattern.

Chaos Theory

Chaos theory, considered to be a subset of complexity science, emerged from the early work of Edward Lorenz in the 1960s to improve weather forecasting techniques. Non-human-induced responses in the environment indicate there is some predictability in random patterns (Thietart & Forgues, 1995; Wagner & Huber, 2003). Lorenz found that even small changes of randomness in a system that constantly changes can dramatically affect the long-term behaviour of that system and make it difficult to predict future outcomes. Interestingly, this non-linear model refers to a controlled randomness, which may be associated with recognizable and somewhat predictable patterns.

Chaos theory may be another way to structure change processes in a highly complex and evolving health care environment. Despite the best of intentions to improve organizational function and improve quality and safety of patient care, contextual factors may not be fully explored or considered in the change process. For example, instituting a care delivery model on a unit may not work well if staff have not been appropriated the necessary resources to provide care. Knowing how non-linear theories work can advance organizational functioning in health care organizations and systems in the twenty-first century.

Essential Learning Activity 9.4.1

Watch Claire Burge’s TEDx Talk titled “The Future of Work is Chaos” (13:43) for a more in-depth understanding of chaos theory.

Essential Learning Activity 9.4.2

Cindy is an RN with three years’ experience working on a busy surgical unit in a large urban hospital. Cindy enjoys her job and is keen to pursue an intensive care course after which she plans to work in the intensive care unit of the same hospital. She has received a one-year grant to establish a cardiac program for patients and caregivers. This project will be evaluated at the end of one year. Cindy, as the change agent, is tasked with implementing the change. Stephanie, the nurse manager, is highly supportive, but some of the nurses don’t have time and are not willing to help make the program a reality.

How should Cindy proceed with the change process? Could Lewin’s change theory be used to guide the change? If so, how would you envision the change occurring?

How can she persuade other nurses to buy into the change? What effective leadership and followership strategies could she implement in the change process?

9.5 The Nursing Process as the Change Process

The change process can be related to the nursing process and is described by Sullivan (2012) in four steps. Assessment, the first step, entails identifying the problem. It involves collecting and analyzing data. Pinpointing the problem enables individuals affected by a proposed change to have a clear and accurate understanding of the problem.

Once the problem is identified, the change agent collects external and internal data as needed (e.g., patient satisfaction questionnaires, staff surveys). A critical analysis of the data supports the need for change, at which point the change agent determines resistance, identifies potential solutions, and begins to develop consensus regarding change. Assessing the political climate by determining who will benefit from the change, accessing resources, and having credibility with and respect of the staff will enhance the leader’s ability to increase the driving forces and reduce the restraining forces (Lewin, 1951). Sullivan (2012) recommends converting data into tables or graphs, thus making the results easier for administration and frontline providers to understand, and perhaps accept, the change.

Planning requires the participation of staff that will be affected by the change. Relationships among staff may be altered if structures, rules, and practices are modified. This in turn alters workforce requirements, which may then lead to hiring new people with different skills, knowledge, attitudes, and motivations (Sullivan, 2012). It is anticipated that less resistance will be encountered if staff are involved at the planning stage, since attitudes, ways of thinking, and behaviours need to shift to accommodate a new way of working.

Weiss and Tappen (2015) recommend three tactics that can be used to unfreeze members or staff. First, sharing information is a way to help staff understand the rationale for a proposed change. Second, disconfirming currently held beliefs is a way to demonstrate that a current goal of the target system is inadequate, incorrect, or inefficient and therefore needs to be modified. Third, providing psychological safety is a tactic that minimizes risk by affording sufficient security to staff. This tactic is highly valuable as it generates a feeling of security and facilitates members’ ability to trust and accept the change. These three tactics decrease anxiety about the change. Establishing target dates and time frames to determine progress and providing opportunities for members to offer feedback will support the change.

In the implementation stage, plans are put into action. The change agent sets the tone for a positive and supportive climate, and methods are used to continue persuading members toward the change (providing information, training, assisting with personnel changes). Strategies are used to change the group dynamics to encourage members to act based on group decisions.

During evaluation, indicators are monitored to determine whether goals have been met, and what, if any, undesirable outcomes occurred and how to respond to unintended consequences. Once the desired outcome is reached, the change agent terminates the role by delegating responsibilities to members. Policies and procedures may be necessary to stabilize the change as part of everyday practice. The leader, as energizer and supporter, continues to reinforce behaviours through ongoing feedback.

9.6 The Medicine Wheel as a Change Model

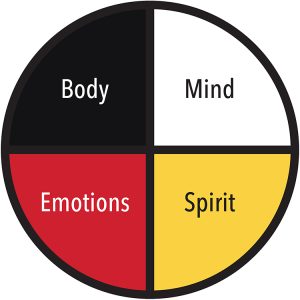

The medicine wheel, drawn as a circle with four quadrants, represents a holistic set of beliefs encompassing the mind, body, emotions, and spirit, which is foundational to the human being. These beliefs have been embraced by Indigenous cultures across the world for thousands of years (McCabe, 2008). Carl Jung and others emphasized this dialogue between the four aspects of the human being as a way to understand self and maintain health (McCabe, 2008). Psychologists recognize the medicine wheel as “the Jungian mandala—a symbol of wholeness” (Dapice, 2006, p. 251).

Figure 9.6.1 Medicine Wheel

The medicine wheel is found in the teachings of individual Elders in over 500 Indigenous nations across Canada. Teachings are similar between the nations; however there are slight differences regarding the location of the four dimensions on the wheel (Clarke & Holtslander, 2010). The medicine wheel is manifested within the community as a “process (healing), a ceremony (sweats, sharing circles) and teachings (a code for living)” (McCabe, 2008, p. 34). The Indigenous people consider the community participation in ceremonies to be an important part of the healing process (McCabe, 2008). The medicine wheel assists community members to connect with each other, while also supporting balance and harmony across the four dimensions of mind, body, emotions, and spirit for the individual and the extended community (Clarke & Holtslander, 2010).

Recent literature focuses on the use of the medicine wheel to recover from illness and regain health. The medicine wheel guides healthy change and can be individualized to the specific needs of the client or community, taking into account the context of culture, socioeconomic status, family situation, disease process, and other significant factors, culminating in balance, healing, and growth in all four aspects. Research literature documents the use of the medicine wheel in diabetes education (Kattelmann, Conti, & Ren, 2010), end-of-life care for Aboriginal people (Clarke & Holtslander, 2010), substance abuse prevention programs (Walsh-Buhl, 2017), adolescent group counselling (Garner, Bruce, & Stellern, 2011), and development of a retention program for diverse nursing students (Charbonneau-Dahlen, 2015). The medicine wheel provides a guide to holistic change for both the individual and the collective community.

Essential Learning Activity 9.6.1

Watch the video “Medicine Wheel: Beyond the Tradition” (9:20), for an explanation and overview of the Lakota (Sioux) medicine wheel, according to Don Warne, then answer the following questions:

- What does the medicine wheel represent?

- How does the use of the medicine wheel extend from traditional to modern times?

- Which gifts come from each of the four directions?

9.7 The Nurse Leader’s Role in Managing Organizational Change

The nurse leader’s role as change agent is complex and varied in nature, and it represents significant leadership challenges. Innovative organizational change can be effectively managed with proven leadership strategies and tools (MacPhee, 2007). The change agent has two main responsibilities: to change oneself and to build capacity in others. Stefancyk et al. (2013) introduced the idea of a change coach, which builds upon the traditional role of a nurse leader. A change coach or leader uses coaching behaviours that include guidance, facilitation, and inspiration (Stefancyk et al., 2013). The leader uses guidance to set behavioural expectations for staff performance and provides feedback on performance in the change project. As a facilitator, the change coach encourages staff to share in decision making, thereby creating and nurturing a culture that supports input from others, facilitates creative thinking, and enhances the process of finding the best solutions to address challenges. The leader takes on an inspirational role, expressing confidence and recognizing staff as providing meaningful contributions to the change process.

Building partnerships with staff that include two-way communication, both internally and externally, is critical to building trust and teamwork (Gilley et al., 2009; Yukl, 2013). Communication strategies can include informing those affected by the change how the change will affect their job, and providing information in a timely manner to help them make effective decisions. Nurse scholars (MacPhee, 2007; Morjikian, Kimball, & Joynt, 2007; Stefanyk et al., 2013) suggest that developing trust is a component of communicating effectively, and that this can be accomplished through demonstrating approachability, building rapport, listening, and restating the opinions of others (even when the leader disagrees with the opinion). Listening to staff also means being aware of change fatigue, a condition experienced by individuals subjected to unrelenting and overwhelming change in their work environments (Bowers, 2011). Leadership and management skills and behaviours can positively influence the execution of change initiatives (Gilley et al., 2009).

A call to action means the leader knows when strategies for change need to be altered to foster effective followership. Navigating complex organizational structures through formal and informal power networks is foundational to setting the stage for a successful change. Organizational agility requires the leader to know and understand how the organization works and to be familiar with key policies, practices, and procedures.

9.8 Change Strategies

According to the classic model developed by Bennis, Benne, and Chinn (1960), three strategies can be used to facilitate change. The characteristics of the change agent and the amount of resistance encountered will determine which of the following strategies should be used.

- Power-coercive strategies are based on the application of power through legitimate authority (Sullivan, 2012). Little effort is used by the nurse leader to enforce change, and staff has no ability to alter the course of the change process. Power-coercive strategies can be used when change is critical, time is limited, there are high levels of resistance, and there may be little or no chance of reaching organizational consensus (Sullivan, 2012).

- Empirical-rational strategies assume that providing knowledge is the most powerful requirement for change (Sullivan, 2012). This strategy assumes that people are rational and will act in their own self-interest when they understand that change will benefit them. It can work well if the change is perceived as reasonable or beneficial for individuals.

- Normative-reeducative strategies assume that individuals act in accordance with social norms and values that influence their acceptance of change (Sullivan, 2012). The nurse leader focuses on individual’s behavioural motivators such as roles, attitudes, feelings, and their interpersonal relationships as an effective way to implement change in the health care environment.

9. 9 Response and Resistance to Change

Several factors can influence resistance to change. It is not uncommon for staff to state that they were not involved in the decision making regarding changes in their practice and, as a result, be highly resistant to change. While not everyone will embrace change, individuals respond on a continuum that ranges from a lack of enthusiasm to overt sabotage (Gaudine & Lamb, 2015). Resistance may involve a personal loss, feelings of inadequacy, lack of competence, and lack of confidence to perform (Austin & Claassen, 2008). Leaders who can help members psychologically own the change are more likely to see the change initiative sustained and embedded in practice.

We offer the following strategies to counter resistance:

- Understand that resistance is a natural part of the process but must be constructively addressed for change to progress.

- Learn why an individual is resisting the change. Perhaps the resistance may be related to the lack of understanding in how the change process unfolds, which calls for supporting their ability to adjust to the change.

- Link some of the old ways of working with the new change as a way to bridge the old with the new and bring some familiarity to new practices (Austin & Claassen, 2008).

- Identify people who are willing to try new practices, which can reduce the possible resistance from others when change is introduced (Bowers, 2011).

- Assist staff in identifying with and valuing how the change will affect their practice (i.e., help them to assume ownership for the change) in order to ensure that the change is embraced and sustained.

- Communicate a clear vision of the benefits to be gained from the change (Yukl, 2013). Structured and transparent communication aids the participation and involvement of staff.

Summary

One of the most difficult activities for the nurse leader is leading change in an organization. The nurse leader needs to have excellent leadership skills, be conversant with change theories, and be able to partner and work effectively with staff in achieving the vision. Being a change coach involves navigating change, generating and mobilizing resources toward innovation, and improving outcomes.

After completing this chapter, you should now be able to:

- Explain why nurses have the opportunity to be change agents.

- Identify how different theorists explain change.

- Discuss how the nursing process is similar to the change process.

- Discuss the medicine wheel as a change model.

- Describe the nurse leader’s role in implementing change and the call to action.

- Differentiate among change strategies.

- Recognize how to handle resistance to change.

Exercises

- How do you normally respond to change in your personal life? How did you respond to your first clinical situation?

- Identify the leadership skills that a nurse leader must apply when implementing change.

- Identify a change occurring in your workplace. Using one of the change theories presented in this chapter, analyze how well the change process is working.

- What are some of the contributing factors to the failure of change projects?

- Reflect on how you as a follower can be a positive asset to a change process.

References

Austin, M. J., & Claassen, J. (2008). Impact of organizational change on organizational culture. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 5(1–2), 321–359. doi:10.1300/J394v05n01_12

Bennis, W., Benne, K., & Chinn, R. (1960). The planning of change (2nd ed.). New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Bowers, B. (2011). Managing change by empowering staff. Nursing Times, 107(32–33), 19–21.

Burnes, B. (2004). Kurt Lewin and complexity theories: Back to the future? Journal of Change Management, 4, 309–325.

Charbonneau-Dahlen, B. K. (2015). Hope: The dream catcher-medicine wheel retention model for diverse nursing students. Journal of Theory Construction and Testing, 19(2), 47–54.

Clarke, V., & Holtslander, L. F. (2010). Finding a balanced approach: Incorporating medicine wheel teachings in the care of Aboriginal people at the end of life. Journal of Palliative Care, 26(1), 34–36.

Dapice, A. N. (2006). The medicine wheel. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 17(3), 251–260.

Drucker, P. (1999). Management challenges for the 21st century. New York: Harper Collins.

Estabrooks, C. A., Thompson, D. S., Lovely J. J. E., & Hofmeyer, A. (2006). A guide to knowledge translation theory. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26(1), 25–36. doi:10.1002/chp.48

Garner, H., Bruce, M. A., & Stellern, J. (2011). The goal wheel: adapting Navajo philosophy and the medicine wheel to work with adolescents. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 36(1), 62–77. doi:10.1080/01933922.2010.537735

Gaudine, A., & Lamb, M. (2015). Nursing leadership and managing working in Canadian health care organizations. Toronto: Pearson.

Gilley, A., Gilley, J. W., & McMillan, H. S. (2009). Organizational change: Motivation, communication, and leadership effectiveness. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 21(4), 75–94. doi:10.1002/piq.20039

Havelock, R. (1973). The change agent’s guide to innovation in education. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology.

Kattelmann, K. K., Conti, K., & Ren, C. (2010). The Medicine Wheel nutrition intervention: A diabetes education study with the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(9), 44–51. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.003

Kouzes, J. M., and Posner, B. (2007). The leadership challenge (4th ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kritsonis, A. (2005). Comparison of change theories. International Journal of Scholarly Academic Intellectual Diversity, 8(1), 1–7. Retrieved from http://commonweb.unifr.ch /artsdean/pub/gestens/f/as/files/4655/31876_103146.pdf

Lehman, K. L. (2008). Change management: Magic or mayhem? Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 24(4), 176–184.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social sciences. New York: Harper & Row.

Lippitt, R., Watson, J., & Westley, B. (1958). The dynamics of planned change. New York: Harcourt Brace.

MacPhee, M. (2007). Strategies and tools for managing change. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 37(9), 405–413.

McCabe, G. (2008). Mind, body, emotions and spirit: Reaching to the ancestors for healing. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 21(2), 143–152. doi:10.1080/09515070802066847

Morjikian, R. L., Kimball, B., & Joynt, J. (2007) Leading change: The nurse executive’s role in implementing new care delivery models. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 37(9), 399–404. doi:10.1097/01.NNA.0000285141.19000.bc

Quinn, R. E. (2004). Building the bridge as you walk on it. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Rogers, E. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (4th ed.). New York: Free Press.

Saskatchewan Ministry of Health. (2011) Patient- and family-centred care: Putting patients and families first. Retrieved from https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/health-care-administration-and-provider-resources/saskatchewan-health-initiatives/patient-and-family-centred-care

Shirey, M. (2013). Lewin’s theory of planned change as a strategic resource. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 43(92), 69–72. doi:10.1097/NNA.0b013e31827f20a9

Stefancyk, A., Hancock, B., & Meadows, M. T. (2013). The nurse manager: Change agent, change coach? Nursing Administration Quarterly, 37(1), 13–17. doi:10.1097/NAQ.0b013e31827514f4

Sullivan, E. J. (2012). Effective leadership and management in nursing (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Thietart, R. A., & Forgues, B. (1995). Chaos theory and organization. Organization Science, 6(1), 19–31.

Tyson, B. (2010). Havelock’s theory of change. Retrieved from http://www.brighthubpm.com/change-management/86803-havelocks-theory-of-change/

Wagner, C. M., & Huber, D. L. (2003). Catastrophe and nursing turnover: Nonlinear models. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 33(9), 486–492.

Walsh-Buhl, M. L. (2017). Please don’t just hang a feather on a program or put a medicine wheel on your logo and think ‘oh well, this will work.’ Family and Community Health, 40(1), 81–87. doi:10.10 97/FCH.0000000000000125

Weiss, S. A., & Tappen, R. M. (2015). Essentials of nursing leadership and management (6th ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis.

Wonglimpiyarat, J., & Yuberk, N. (2005). In support of innovation management and Roger’s Innovation Diffusion Theory. Government Information Quarterly, 22(3), 411–422. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2005.05.005

Yukl, G. (2013). Leading in organizations (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.