Unit 3: Migration Data

Section 1. Migration data: definitions, importance, indicators

1.1 How do we define migration data?

The UN’s International Organization for Migration (IOM) states:

“Migration data includes all data that support the development of comprehensive, coherent, and forward-looking migration policies and programming, as well as those that contribute to informed public discourse on migration. This includes data on different forms of population movement, whether short or long-term, forced or voluntary and cross-border or internal, as well as data concerning characteristics of movement and those on the move, and the reasons for and impacts of migration” (IOM-UN Migration 2021b).

The UN recommends defining the short-term international migrant as “a person who moves to a country other than that of his or her usual residence for at least 3 months but less than a year” (United Nations 1998, p. 10).

The long-term international migrant is defined as “a person who moves to a country other than that of his or her usual residence for at least a year, so that the country of destination effectively becomes his or her new country of usual residence” (ibid).

Temporary travel abroad for purposes of recreation, holiday, visits to friends and relatives, business, medical treatment or religious pilgrimage does not change a person’s country of usual residence in either cases (ibid).

Even if a person obtained citizenship in their new country, they are still counted as immigrants in migration statistics.

For emigrants the rules are similar. If they have left their home country for more than a year, they are considered long-term emigrants, even if they acquired citizenship in their country of destination.

Please note that some national governments may use different definitions to those recommended by the UN.

Exercise 3.1

In your opinion:

- What is the benefit of having separate data on short-term and long-term international migrants?

- What role do the factors of time, distance and reason for migration play in choosing the appropriate definition?

1.2 What is the institutional framework for global migration data collection?

In 1976, the UN adopted the Recommendations on Statistics of International Migration encouraging countries to collect quality and comparable data on migrants. In 1998, these were revised and expanded to include special guidelines on data on asylum seekers (United Nations 1998).

However, these recommendations are not binding and require significant funding to be properly implemented across the globe, especially in countries with fewer resources to conduct regular and comprehensive population censuses.

The importance of migration data is highlighted by several, albeit non-binding, international agreements that encourage countries to collect relevant data to inform evidence-based policy decisions. These are:

- 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development;

- Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM);

- Global Compact on Refugees (GCR);

- Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030

To coordinate a broad range of actors working with migrants and on migration (national and regional authorities, NGOs, international agencies and the private sector), the UN established two expert groups to foster the collection of better migration data and provide recommendations on the collection of data about specific groups of migrants. They are:

- Expert Group on Migration Statistics (United Nations 2025)

- Expert Group on Refugee, IDP and Statelessness Statistics (EGRISS 2025).

Exercise 3.2

Choose one of the primary documents from the preceding list.

- How does it argue for the importance of migration data?

- What purposes does the document highlight for collecting and using migration data?

1.3 Where do we look for up-to-date migration data?

Several institutions collect and analyse different types of migration data related to various groups of migrants or migration-related social phenomena (migrant children, refugees, IDPs, remittances, diaspora, migrant health, etc.)

Among the most important sources of migration data are the following:

- the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs,

- the World Bank Group,

- the International Organisation for Migration,

- the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD),

- the International Labour Organisation,

- UNHCR,

- Eurostat,

- the Knowledge Centre on Migration and Demography (European Commission’s DG HOME).

Some of the key databases where you can find long-term comparative global or regional migration data are:

- Migration Data Inventory

- Our World in Data

- World Migration Report 2024

- IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix

- World Bank-UNHCR Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement

- UNHCR Global Trends Report

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre

- Mixed Migration Centre 4Mi data

- Knowledge Centre on Migration and Demography (KCMD) Knowledge4Policy

Exercise 3.3

Choose one of the databases and find the relevant section explaining how the data was collected and analysed.

- Are limitations to the data explicitly mentioned?

- How are these limitations explained?

For most up-to-date national-level statistics, you should consult the resources of relevant National Statistical Offices.

Please note that other state institutions may also collect migration-related data for their own purposes, and they could be using other methodologies of data collection (e.g. regional or local governments, divisions of national ministries responsible for labour, social policy, development, health).

Exercise 3.4

Go to the website of your national statistical office and look at the kind of migration data it collects and publishes.

- How is migration data collected?

- What kind of migration data is missing?

- Is the data up-to-date?

- Are there limitations to the migration data available from your national statistical office?

1.4 Why is migration data important?

We still know surprisingly less about migration than we should. Migration data experts agree that relatively few quality statistics on international migration are collected globally.

We know more about migrant stocks and remittances, but much less about migrant flows (especially emigration), about the health, working and living conditions, the integration of migrations, and the scale and dynamics of return migration (Laczko, Mosler Vidal, and Rango 2024, p. 17).

Nonetheless, migration data collection serves multiple purposes (see Figure 3.1).

Governments rely on information about the number, geographic distribution and flows of people on their territory to plan and manage public resources. Informed discussion and effective policymaking must rely on good migration data about the country, its different parts, but also about the wider region to forecast possible cross-border movements (van Teutem and Acisu 2024).

Policymakers are also interested in migration-related data, such as public attitudes to migrants, remittances (the money sent home by migrants), and data on the impact of migration policies and programmes.

Decision-makers also want to know past, present or future trends and forecasts of various migration flows (conflict or disaster-induced, environmentally-connected), different migrant groups and their characteristics, or to estimate the impact of global events on human mobility (such as COVID-19 pandemic).

However, having the data is not enough. Data requires careful analysis and effective communication to have an impact.

Migration data is also used for decision-making, advocacy, planning, and budgeting by governmental institutions and non-profit sectors working with specific migration-related issues or groups.

Exercise 3.5

Communication between researchers, policymakers and practitioners is essential if we want policy decisions and non-profit sector activity to be based on evidence and sound analysis.

Access The Migration to Research Policy Co-Lab to learn more about how your (future) research can be useful, practical and applicable for non-academic audiences.

- Who might be interested in your research from within the policy and practitioner community?

- How would you engage with them to make your research known and useful for them?

1.5 International migrant stocks and flows – key migration data indicators

Please note, in this topic we will use official definitions used in migration statistics – migrant stocks and migrant flows – yet keep in mind that they are sometimes criticized for giving negative connotations to migration and migrants.

Definition: Immigrant/Emigrant Stock

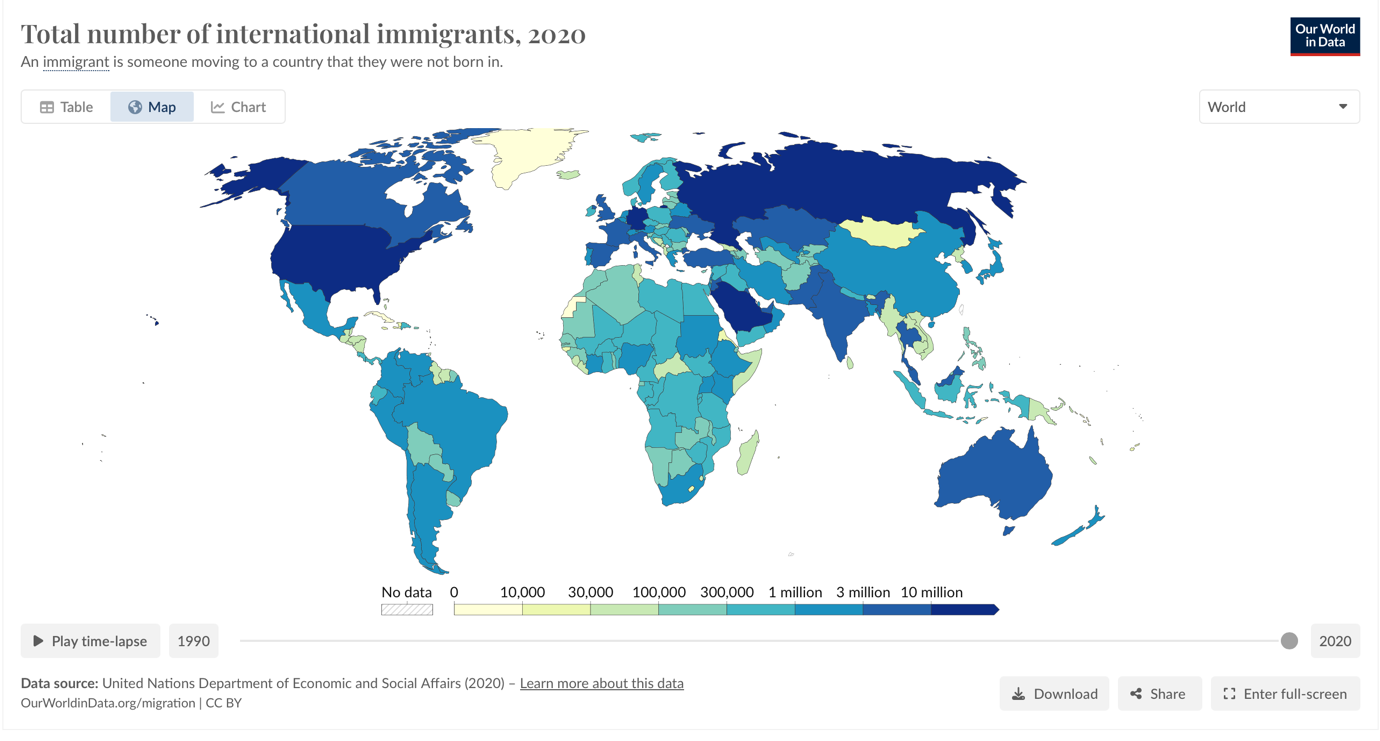

“The total number of international migrants present in a given country at a particular point in time” (United Nations 2022, p. 11) is called the international immigrant stock. (Figure 3.2)

“The emigrant stock is equal to the total number of emigrants from a given country at a particular point in time” (ibid).

International migrant stocks measure the number of ‘foreign-born’ populations living outside the countries of their birth.

These stocks are produced by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs based on national statistics derived from censuses (Laczko, Mosler Vidal, and Rango 2024). So far, such estimates are available for 232 UN countries/areas; they are updated regularly providing information about the labour migrants, family migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

However, they are not perfect measures due to a number of data limitations, for instance, difficulties with estimating the number of irregular migrants, homeless migrants or unaccompanied migrant children not included in national censuses.

Apart from censuses, the UN also uses data from population registers or surveys, as well as methods of interpolation (filling gaps in the data) and extrapolation (predicting future trends) (van Teutem and Acisu 2024).

Emigrants are also difficult to count for domestic governments as they are not included in national censuses or household surveys, and there are few incentives for emigrants to register their departure. Therefore, governments either have to survey the household members of emigrants and ask about them, or to use other countries’ data to estimate the number of their co-nationals in these countries (Laczko, Mosler Vidal, and Rango 2024).

National censuses are time-consuming, costly to collect and usually produce data with some delays. This is why the latest data we have in early 2025 is for the year 2020.

The second key migration data indicator are migration flows, defined as the “number of migrants entering and leaving a given country during a given period of time, usually one calendar year” (United Nations 2022, p. 11).

If more people come to a country, then its net migration rate (the difference between immigration and emigration) is positive: its population is growing. In contrast, a negative net migration rate indicates that more people are leaving the country than entering: its population is shrinking.

Exercise 3.6

Calculate the annual net migration rate for your country using the interactive Population & Demography Data Explorer from Our World in Data.

- Did your country of origin or current residence have more people immigrating or emigrating in 2023?

- How has the trend in net migration changed over time?

To count migration flows, countries use surveys and registration systems: residence permits, visas, asylum applications, and other immigration documents. Some countries also rely on population registers of moves when people must register when taking up employment; others rely on self-reporting by migrants, which is not always reliable.

Depending on a country’s resources, its ability to estimate migration flows using various sources differs. In particular, the ability to control its land borders is significant in making reliable migration flow estimates.

Emigration is again even more difficult to monitor as few countries have sufficient incentives in place to motivate their citizens to register or declare their departure from the country.

Knowing the gaps in the data and the limitations imposed by such gaps is necessary for anyone working with migration data.

Please remember that data about migration flows is often a byproduct of current political priorities, such as border security or concerns about ‘irregular migration’. Data are collected by different governmental agencies often without much coordination, and do not always correspond to the needs of other institutions or users.

Moreover, such data might be misinterpreted if users lack the necessary data literacy and expertise to evaluate the quality of data collected, its comparability with other time periods and across geographies.

Some data might be inaccessible due to legal, technical or practical obstacles or due to the lack of trust between different agencies or stakeholders.

Even if data is available, some institutional actors or users might decide not to use it because of their policy priorities or due to the lack of necessary resources to process such data (J. Slootjes and Sohst 2024).

Exercise 3.7

Check the website of your national border guards’ agency.

- Does it publish data about the number of border crossings from and to the country?

- How does this data correspond with the data on migration flows you have seen on the interactive Population & Demography Data Explorer?

- Do you see any discrepancies between the numbers? How can you explain them?

Please remember that the number of border crossings does not mean the number of persons crossing the border! One person can make multiple cross-border trips, and they will all be counted.

1.6 What is irregular migration?

What about data on ‘irregular migration’ (often referred to as ‘illegal’, ‘unauthorised’ or ‘undocumented’) – movement of people outside of the legal rules of entering, leaving and staying in the country?

There are many groups of migrants whose migration can be characterised as ‘irregular’:

- those who cross the border without the necessary legal permissions (e.g. visas) or outside of regular border crossing points;

- those who enter legally, but overstay their visas;

- those who enter the country under one permission (e.g. for study) but also engage in paid employment not allowed by their visas (J. Slootjes and Sohst 2024).

For governments, it is obviously difficult to track and count irregular migration, especially when it occurs in free movement zones, such as the Schengen zone in Europe, ECOWAS in Africa or MERCOSUR in Latin America. In addition, more people are working remotely with mixed tax and living residences.

Contrary to media images of migration as being dominated by irregular migration, the estimated numbers are much smaller. For instance, in the UK the share is 7%, in Germany 4%, in France 3%, and in the Netherlands 2% (van Teutem and Acisu 2024).

Exercise 3.8

Check the MIrreM Public Database on Irregular Migration Stock Estimates which provides estimates of irregular migration stocks in 13 European countries, the United States and Canada for the period 2008 to 2023.

- Which country has the highest estimated number of irregular migrants?

- What are the trends in the number of irregular migrations over the years?

- What are the sources of this migration data?

You have now completed Section 1 of Unit 3. Up next is Section 2: What are the sources of migration data, their strengths and limitations?