Unit 3: Migration Data

Section 3. How is migration data politicized?

3.1 Migration research and politics

Exercise 3.13

Before we dive into this section, you can take the QuantMig migration quiz in order to test your current knowledge and perception of the level of current migration and potential future trends of migration.

- Did your guesses correspond to the estimates provided by the Quiz?

- If not, have you overestimated or underestimated current and future migration levels?

- Why do you think this was the case?

Please remember that all migration numbers are only approximate. In reality, all estimates and future scenarios come with errors.

Even though the future of migration flows and stocks is uncertain, migration is usually a hotly debated topic in the public sphere and media. We see claims about the total number of migrants being ‘too high’ (compared to what and when?) and trends becoming ‘increasingly alarming’ (for whom? Why?).

Despite migration researchers’ attempts to bring facts and other collected evidence to the public sphere and to the attention of policymakers, “just spreading ‘facts’ doesn’t work. Politicians and other policymakers will ignore the facts they find inconvenient” (de Haas 2023).

So why is migration in general, and migration data in particular, so often politicized? How should we address this issue as (future) migration researchers?

Another challenge with migration data is that politicians might be interested in concealing ‘inconvenient data’, exaggerate or diminish the numbers of certain migrant groups for political purposes (Cardona-Fox 2020) or, as one data expert said: “around the world, the pressure to fiddle the figures is real and widespread” (Harford, 2020, p. 204 quoted in: Laczko, Mosler Vidal, and Rango 2024, p. 7).

The debate about to what extent migration research should be ‘policy-relevant’ has been going on for a long time (Bakewell 2008). The utilitarian and instrumental turn in the early 2000s also contributed to the reinforcement of the link between knowledge and politics, as research and researchers were increasingly “expected to be both useful and usable for solving political problems” (Dodevska 2024, p. 3).

A trend for technocratic ‘evidence-based policy’ (at least in name), supposedly free from emotions, personal interests and ideological preferences and capable of solving previous policy deficiencies, led to collaborations where scientific evidence was often used to legitimise necessary political decisions rather than challenging inefficient policies or providing working solutions.

For now, the impact of migration research on migration policies seems to be rather limited and sporadic (Natter and Welfens 2024).

Exercise 3.14

We started this unit with a quote “If it is not measured, it doesn’t exist. If it is not counted, it doesn’t count” (Andreas and Greenhill 2010, p.1). In a world where numbers are omnipresent, some experts argue that “having more migration data will lead to better lives, while others are more sceptical about the value of having more information” (J. Slootjes and Sohst 2024).

What is your view based on the information from this unit?

3.2. How do we define and characterise politicization?

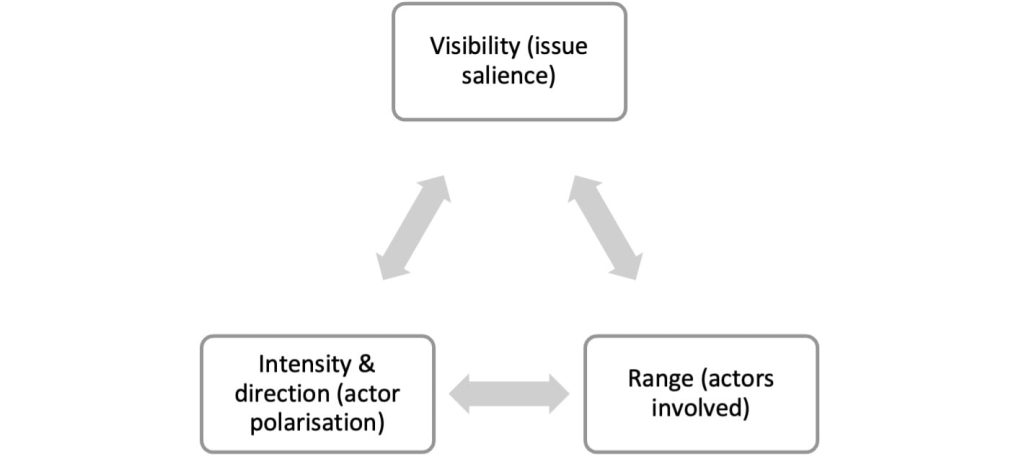

Politicization is “moving something into the realm of public choice” (Zürn 2019, p. 978). Usually, when a topic is politicized, it leads to “an expansion of the scope of conflict within the political system” (Hutter and Kriesi 2021, p. 3) by involving a larger number of actors, more intensified debates and increased visibility in the public sphere (Figure 3.7).

In short, when significant groups of people publicly disagree about an important topic which leads to political decisions, we can say it became politicized.

The easiest way to see the extent of the politicization of migration is to open any major national or international media outlet. You will most probably find news about some aspect of migration being discussed, be it the need for labour migration, the challenges of migrant integration, e.g. crimes and welfare ‘abuses’, reports about border closures to prevent irregular migration, descriptions of horrific conditions in refugee and IDP camps in one of the major displacement crises countries, and who is responsible for that, etc.

If elections in your country are on the horizon, the topic of migration, be it immigration or emigration, will most probably be high on the agenda of the major parties and a topic of controversial electoral proposals and debates.

Exercise 3.15

Choose one of your favourite national or international news media, look through the headlines and see if any topics related to migration appear to be in the middle of current political debates in your society.

- What are these debates about?

- Are they based on migration data and evidence? What kind of data?

- How do you evaluate the evidence used in the public sphere related to this topic?

- Is the debate well-informed in your view?

- Who are the main actors in the debate?

3.3. What are the ‘hot’ topics in migration?

Famous migration researcher Hein de Haas in his book How Migration Really Works (de Haas 2023) scrutinised 22 migration myths by using the wealth of migration data and research conducted by generations of scholars. He argues that debates around migration are often simplistic and force us to choose between either pro or anti-migration side, whereas, in fact, migration is neither a problem nor a solution to other problems.

Migration “as an intrinsic and therefore inseparable part of broader processes of social, cultural and economic change affecting our societies and our world, and one that benefits some people more than others, can have downsides for some, but cannot be thought or wished away” (ibid).

In other words, migration is a complex phenomenon that should be analysed in a particular social and geographical context. Migrants are neither all ‘good’ ‘victims’ or ‘heroes’, nor all ‘bad’ ‘criminals’ or ‘illegals’. Migrants are, first and foremost, people in search of better livelihood opportunities and safety. Migration has existed as long as humanity and is an inherent part of social life.

Politicization also makes the discussion not only simplistic but also narrowly focused. Current political debates about the levels and trends of migration tend to make alarming announcements about ‘unprecedented’ numbers of migrants coming to Europe or North America and build on corresponding fears of shrinking numbers of ‘natives’.

Yet, they ignore, for example, the concerns of the origin countries losing their young and educated labour force who are looking for better employment opportunities, or they remain blind to the legacies of settler colonialism and forced resettlement of indigenous populations.

Migration was and continues to be a complex and ambiguous social process where easy political pro- or anti-migration declarations will provide little in the way of substantive answers. Research shows that people have more nuanced opinions about migration and migrants by having simultaneously valid concerns about immigration, border protection or integration, and positive attitudes towards migrants they personally know.

Exercise 3.16

Check the 2024 Ipsos global report on attitudes towards refugees across the globe. Find your country or choose any other covered by the survey and compare it to other countries in the region or globally in terms of openness to refugees.

Why do you think these opinions differ?

Another ‘hot’ topic of political debate is the anticipation of huge waves of environmentally induced migration due to climate change (floods, droughts, tsunamis, etc.).

The World Bank has published two “Groundswell” reports predicting that climate change could force up to 216 million people across six world regions to move within their countries by 2050 (WBG 2018; 2021).

However, even this number will represent less than three percent of the likely total expected population in the affected regions, whereas other affected populations will most likely remain in the nearby areas or will return to the climate-affected regions if conditions permit.

To put it simply, the alarmist predictions that all those impacted will become migrants/refugees are not very likely to materialise.

Exercise 3.17

Check the World Bank reports Groundswell Part 1: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration and Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration reports for information about your country.

- What are the projections about the level of environmentally induced migration in your country/region?

- What kind of data are used to predict such migration flows?

You have now completed Section 3 of Unit 3. Up next is a collection of resources and additional readings for this unit.