Unit 5: Defining Refugees

Section 1: What is the historical context to the developing concept of refugeedom?

This first section considers why this particular time and place in history is of such significance.

We’ll then go on to look at the importance of key concepts and definitions in the study of the topic.

The section finishes with a consideration of the ‘historicization of refugees’ and an account tracing the emergence of refugeedom.

1.1 What’s at stake?

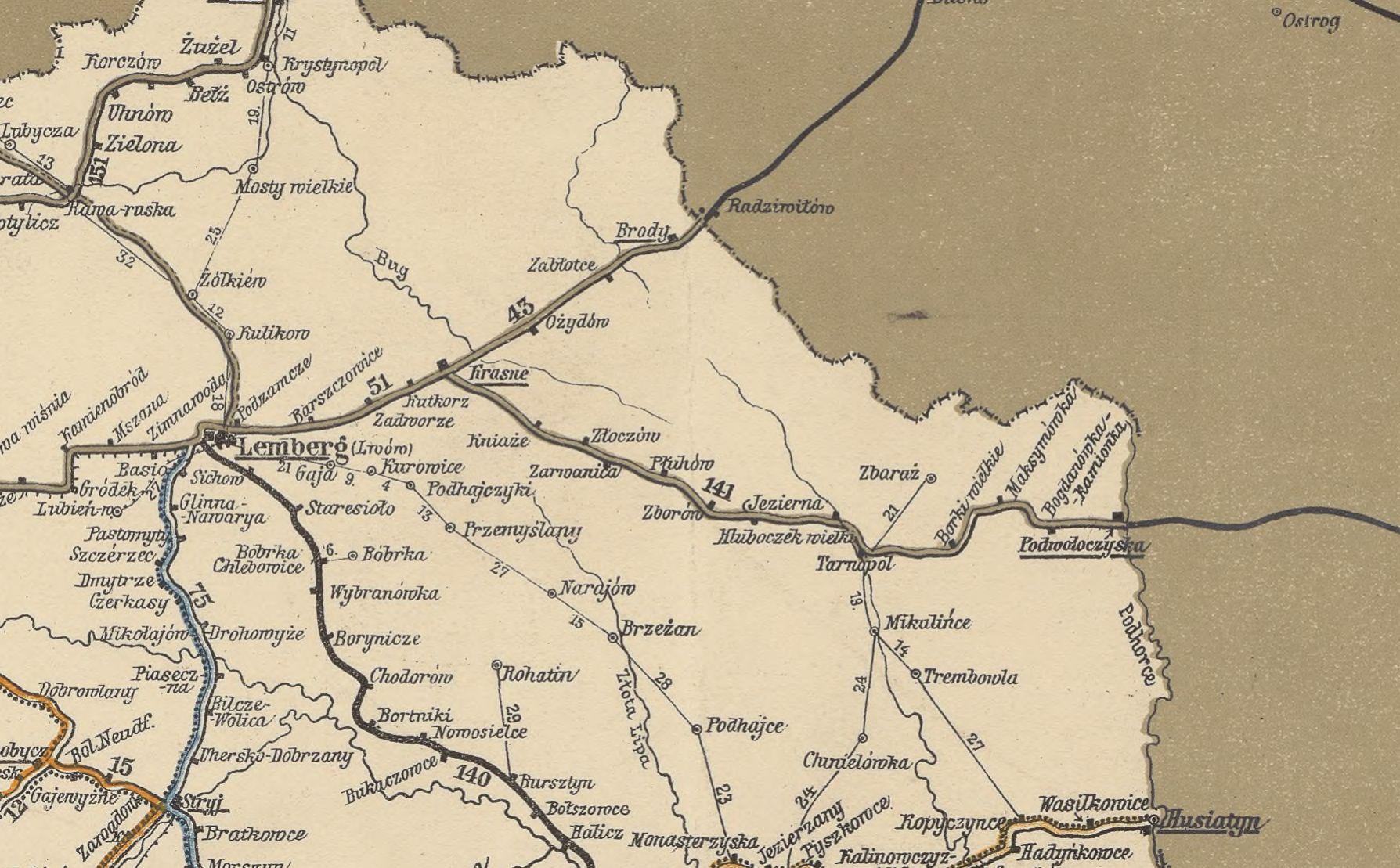

The late nineteenth century witnessed an unprecedented movement of people across and beyond East Central Europe. This region, situated between the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and German Empires, became a dynamic space where imperial border regimes, nationalist ideologies, and global migratory trends collided.

Among the most vulnerable populations were Jews fleeing escalating antisemitic violence and discrimination in the Russian Empire. Their flight, though unplanned and legally undefined, bears many of the hallmarks of modern refugee movements, such as:

- sudden departure;

- lack of documentation;

- dependence on humanitarian aid;

- contested political status.

In the absence of international refugee law or formal asylum mechanisms, states and societies responded in ways that were often improvised, fragmented, and politically ambivalent.

This unit examines how these actors—including imperial authorities, municipal administrations, and transnational Jewish organizations—navigated the crisis, as well as how the displaced individuals themselves experienced and negotiated their uncertain status.

By focusing on the province of Galicia, this unit examines how imperial peripheries became critical spaces for the articulation and contestation of emerging categories of mobility.

It reveals how the historical borderlands of East Central Europe anticipated many of the dilemmas that would later define refugee policy in the twentieth century.

1.2 What are the key concepts and definitions we need in studying this topic?

Understanding forced migration in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries requires careful attention to the vocabulary used to describe people on the move.

Terms such as ‘refugee’, ‘migrant’, ‘exile’, and ‘transmigrant’ carry specific legal, political, and cultural meanings that have shaped how displaced populations have been categorized and treated.

In the absence of an international legal framework, categories were often fluid, contested, and strategically employed by governments, relief organizations, and the migrants themselves.

This section introduces several key terms central to analyzing the Galician refugee crisis and situates them within the broader historical and administrative context of East Central Europe. These are:

- refugee

- migrant

- exile

- transmigrant

Definition: Refugee

In the modern sense, a refugee is a person who flees persecution, violence, or conflict and crosses an international border in search of protection. In the late nineteenth century, however, the term had no formal legal status and was applied inconsistently. Many displaced persons who would now be considered refugees were treated as irregular migrants or wanderers. The term often carried moral, rather than juridical, weight, and its usage varied depending on political context and the identity of the displaced.

Definition: Migrant

Migrant denotes a broad category encompassing all individuals who move from one location to another, either within a state or across borders, for reasons ranging from economic opportunity to personal security. The term is somewhat flexible, encompassing both voluntary and involuntary forms of movement.

Definition: Exile

Exile is a term often associated with politically motivated displacement. It implies a forced removal or flight due to persecution or opposition to state authority. Exile carries connotations of loss, injustice, and often a longing for return. In the context of Jewish history, exile also resonated with religious and historical narratives.

Definition: Transmigrant

A transmigrant is a person who crosses a territory en route to another destination. This term was often used by scholars of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to describe individuals passing through Europe en route to America or other distant destinations. The concept highlights the temporality and liminality of certain migratory experiences.

1.3 What do we understand by the ‘Historization of Refugees’?

As Peter Gatrell has compellingly argued, refugees are not merely the products of humanitarian crises — they are deeply embedded in the modern world’s political, social, and cultural histories.

This approach challenges us to view refugees not only as victims in need of compassion, but also as historical subjects whose status is shaped through specific institutional, legal, and discursive practices.[1]

Rather than assuming the existence of a static category of ‘refugee’, historicizing the phenomenon allows us to consider how this category has been constructed, contested, and used at different historical moments.

Moreover, this unit stresses the historical agency of people on the move. They were not simply forced out but often had agency over where and when to go, and how to move.

It is no coincidence that much of the historiography on refugees in Europe has focused on the First and Second World Wars—periods marked by the mass displacement of millions and the institutionalization of refugee protection.

The violence of these wars, along with the collapse of empires, ethnic cleansing, and shifting borders, created unprecedented levels of forced migration and drew international attention to the plight of displaced populations.

Scholars such as Peter Gatrell and Philipp Ther emphasized how these conflicts transformed the way states and humanitarian actors conceptualized and responded to displacement. [2]

Gatrell’s notion of ‘refugeedom’ captures the complex interplay between lived experience, administrative categorization, and humanitarian intervention. It refers not only to the condition of being a refugee, but also to the broader political and bureaucratic systems that emerged to manage, define, and often control displaced populations.[3]

Applying this concept to the Galician refugee crisis of the early 1880s enables us to trace the prehistory of refugee regimes and recognize how the mechanisms of labeling, surveillance, and assistance were already taking shape before the disasters of the twentieth century led to their global institutionalization.

1.4 How did the idea of refugeehood emerge?

In the late nineteenth century, refugees had an uncertain and ambiguous status.

There was no international legal framework, no Geneva Convention of 1951, and no High Commissioner to determine who qualified as a refugee or what rights they should be afforded.

Instead, the classification of displaced persons was negotiated on a case-by-case basis, influenced by political concerns, social prejudices, and humanitarian discourses.

The people who fled pogroms in the Russian Empire in 1881–1882 were not legally recognized as refugees by the Habsburg state. They were described as ‘newcomers’, ‘vagrants’, or simply ‘Russian Jews’, and their treatment varied depending on their location, the actors involved, and the prevailing political climate.

The absence of legal definitions did not mean the lack of recognition. Relief agencies and Jewish communal organizations framed the crisis in explicitly humanitarian terms.

International Jewish networks, such as the Alliance Israélite Universelle and the Anglo-Jewish Association, described the displaced as ‘refugees’ to appeal to Western donors and mobilize aid.[4]

Thus, the category of refugee functioned as a rhetorical tool and a moral claim, even though it lacked legal status, and a large number of Jews arriving from the Russian Empire did not fully qualify for this definition.

Scholars argue that the emergence of refugee regimes must be understood within the context of imperial decline, the rise of nation-states, and ideas of sovereignty and humanitarian responsibility.

The Jewish refugee crisis in Galicia was a precursor to later, more institutionalized forms of refugee governance, demonstrating how bureaucracies and civil societies alike experimented with systems of categorization, surveillance, and care.

To historicize refugees is not only to study their movements and hardships but to assess how societies have constructed their meaning critically.

The Galician case shows that even before refugee status was codified, displaced people were being labeled, managed, and governed in ways that laid the groundwork for the modern refugee regime.

Review Exercise

We have now come to the end of the first section in the unit. Complete the following exercises based on what you have learned.

Exercise 5.1

Look over the contents of Section 1 and answer the following questions to check your understanding:

- Why is it important to recover the voices and agency of displaced individuals in historical narratives?

- What are the reasons why scholars study early refugee movements like the one in Galicia, even though they occurred before international refugee law was established?

You have now completed Section 1 of Unit 5. Up next is Section 2: What is the historical context needed for our understanding of the topic?

- Peter Gatrell, The Making of the Modern Refugee (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 15–20. ↵

- See Philipp Ther, The Outsiders: Refugees in Europe Since 1492 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019); Peter Gatrell, A Whole Empire Walking: Refugees in Russia During World War I (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005). ↵

- Peter Gatrell, A Whole Empire Walking: Refugees in Russia During World War I, 171-196. ↵

- Klier, John D. Russians, Jews, and the Pogroms of 1881–1882 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 255-383. ↵