Unit 5: Defining Refugees

Section 3: Case Study: The Jewish Refugee Crisis in Galicia (1881–1882)

3.1 What was the scale of the crisis?

The arrival of Jewish refugees from the Russian Empire into Galicia in 1881–1882 constituted one of the earliest large-scale refugee crises in modern Eastern European history.

Sparked by the violent pogroms, which were followed by sudden and unregulated displacement, it placed extraordinary pressure on the social, political, and administrative fabric of Habsburg Galicia.

Although the crisis lasted less than two years, peaking between the summer of 1881 and spring 1882, it involved an estimated 12,000 to 15,000 refugees, making it a key case for examining the emergence of modern refugee governance in the region.[1]

3.2 Points of Entry and Immediate Reception

Most refugees entered Galicia via informal crossings along the eastern border, using familiar trade and smuggling routes.

The town of Brody—long known as a transimperial Jewish hub—served as the main reception point.

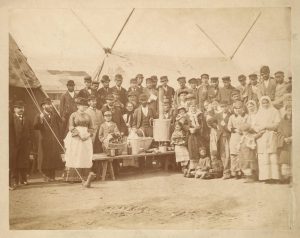

The local Jewish community initially responded with urgency and compassion, organizing food distributions, shelter, and clothing drives.[2]

However, the scale of the influx soon overwhelmed their capacity. Makeshift shelters were established in synagogues, schools, and private homes, but sanitary conditions deteriorated rapidly, sparking fears of disease.

Example

George Price, who arrived in Brody on May 10, 1882, described the situation as follows:

“We arrived in Brody yesterday, God! What a pandemonium! 15,000 Jews are stranded here awaiting their turn. For lack of accommodation, many are quartered in factories situated on the outskirts. Many of them have been here since the last winter. … Jews in different attire and from various cities crowd the streets, and their chattering pierces the heavens.[…]

There is a factory in the city which lodges about 3,000 emigrants and a stable which accommodates 300. In both dwellings, the condition of the emigrants is unbearable. They sit on the floor, huddled together, hungry and thirsty. Besides, there are many emigrants on the streets of Brody and in private homes.”

From: Leo Shpall, The Diary of Dr George Price. Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society Vol. 40, No.2 (December, 1950), pp. 174, 179-180.

3.3 How did the local and imperial government respond to the crisis?

Galician municipalities were largely unprepared.

Some attempted to register and quarantine the arrivals, while others expelled them or redirected them to larger cities such as Lemberg (today Lviv).

In official correspondence, city leaders expressed concern about economic strain, public unrest, and a possible rise in antisemitism.

At the provincial level, the Galician government petitioned Vienna for guidance and support.

The imperial government’s response was intentionally vague: it allowed the refugees to enter but avoided labeling them as ‘refugees’ and quietly promoted onward migration.

This strategic ambiguity allowed Vienna to balance humanitarian impulses with diplomatic caution toward Russia.[3]

3.4 What was the humanitarian response from Jewish Organizations?

In the absence of a coherent state-led effort, non-state Jewish actors took the lead.

Philanthropic networks, such as the Alliance Israélite Universelle in Paris and Vienna, the Anglo-Jewish Association in London, mobilized quickly.[4] They sent funds, dispatched representatives, and launched appeals for aid throughout Europe.

In addition to representatives of international organizations, local initiatives were active on the ground. For instance, the local Jewish community in Brody actively provided assistance to newly arrived Jews with basic necessities in the early stages of the crisis. Local relief committees emerged not only in Lemberg and Brody, but also in several European cities, especially those that were on the route of Jews continuing their journey westward from Galicia.[5]

These organizations framed the crisis in moral and humanitarian terms, portraying it as a moment of Jewish transnational solidarity.

Their interventions enabled many to survive the immediate crisis and to continue westward migration toward Germany, France, or North America.

Towards the end of spring 1882, given a new wave of refugees, the issue of building a permanent settlement for them was raised. However, when philanthropist Baron Hirsch learned about this situation, he bought a non-operational factory, which accommodated several thousand migrants at a time.[6]

Example

George Price, an 18-year-old Jew from Poltava, who stayed in Brody from May to July 1882, dramatically described events that took place at this factory:

“Approaching the entrance to the textile factory, I see thousands of people running back and forth. When I entered the courtyard, I beheld a mass of hungry and thirsty tattered humans. […]

The half of the building where the machines are situated and which is not occupied by the emigrants has 30 windows. The exterior of the building seems to be plastered with people. Since a hill made of sand stretched upward from the yard to the wall the heads of the people seem to join a series of steps… When one sees the picture from a distance, it looks as if the walls are plastered with ants moving one on top of another. Upon closer observation, one is chilled by what he sees. Here a Jew clad in rags and perspiring, who seems to have been here many hours, managed, thank God, to get to the middle. He tries to figure out a way to get to the window as quickly as possible. […] He is beaten, his clothes are rent and finally, still alive, he nears the window, only to be pushed back by a strong armed man who has tried to clear a space. He falls and drags others with him. Immediately, the space is occupied by others. In such an attempt, one is trampled by the mob. The mob pays no attention and goes on fighting and mawling each other in order to get closer to the windows.

[…] inside the building a member of the committee walks pompously from window to window and distributes cards at random. He gives a ticket to one man at one window and to several at another[…].”

From: Leo Shpall, The Diary of Dr George Price, loc. cit. p. 177.

3.5 Who Were the Refugees?

Relief reports highlight the socio-demographic diversity of the refugee population.

Most were poor artisans, peddlers, and laborers.

Families often included women, children, and elderly individuals, highlighting their vulnerable status.

While some hoped to settle in Galicia, most considered it a temporary refuge.

Lacking passports and funds, they were vulnerable and heavily dependent on aid. Local authorities viewed them with suspicion, as a public health and administrative burden.[7]

3.6 Political Effects and Public Debate

The crisis provoked heated debate in the Galician Sejm, the provincial parliament.

Jewish deputies advocated for humanitarian support, while Polish conservatives demanded tighter border controls and questioned the loyalty of the newcomers.

Local newspapers mirrored these divisions: Jewish publications emphasized solidarity and the moral imperative of aid, while Polish nationalist and Catholic outlets warned of social disruption and economic burden.

The refugee issue thus became a flashpoint in broader debates about empire, ethnicity, and migration.[8]

3.7 How was the crisis resolved?

By mid-1882, the crisis began to abate.

Due to support from Jewish migration networks and the reopening of transcontinental routes, many refugees continued westward.

However, a significant portion—especially those without means or support—were forced to return to the Russian Empire.[9]

The episode demonstrated both the potential and the limitations of civil society-led humanitarianism and exposed the institutional fragility of imperial refugee governance.

3.8 Conclusions

The Galician refugee crisis of 1881–1882 offers a case through which to understand how refugeehood was constructed and managed before the development of formal legal definitions.

To be more precise: What exactly was a refugee in the eyes of different actors? How did that change during the crisis? What was the lasting impact, e.g., for Habsburg bureaucrats?

It illustrates the ways in which imperial states, local authorities, and humanitarian actors responded to mass displacement using improvised tools of migration governance – balancing humanitarian concern with concerns about order, diplomacy, and control.

This case challenges simple distinctions between exile and migration.

Many of the displaced were in transit, seeking onward movement rather than long-term settlement, while others were returned to the Russian Empire.

The crisis unfolded in a space where legal categories were uncertain, and responses were shaped as much by local and transnational networks as by imperial policy.

By studying this episode, we see how the foundations of modern refugee regimes were laid not only through international agreements but also through historical practices of negotiation, categorization, and aid at the imperial periphery.

The Galician case helps us better understand refugeehood as a dynamic and historically contingent condition, defined not only by the experiences of those displaced, but by how states and societies choose to respond.

Review Exercises

We have now come to the end of the final section in the unit. Complete the following exercises based on what you have learned.

Exercise 5.3

These questions are designed to encourage you to think critically about the historical materials presented in the unit, connect them to broader themes in migration and refugee studies, and apply analytical concepts in discussion or writing.

- How did the lack of formal refugee law in the nineteenth century shape the treatment and categorization of displaced Jews in Habsburg Galicia?

Consider the implications of legal ambiguity on humanitarian responses, state responsibilities, and the lived experience of refugees. - In what ways did Jewish philanthropic organizations challenge or complement imperial policies during the Galician refugee crisis?

Analyze the role of transnational civil society in humanitarian governance and its influence on public discourse. - How did the social identity of the refugees, particularly as impoverished Eastern European Jews, influence their reception by local populations and authorities in Galicia?

Explore the intersections of class, ethnicity, religion, and migration status in shaping public and institutional reactions. - What can the Galician refugee crisis of 1881–1882 teach us about the origins of modern refugee governance and humanitarianism?

Reflect on how early episodes of displacement influenced the later development of international law and aid practices. - Peter Gatrell argues that refugees are not just humanitarian objects but historical agents. How does this case study support or complicate that view?

Think about how displaced people made decisions, shaped networks, and challenged the categories imposed upon them. - What parallels can you draw between the treatment of Jewish refugees in Galicia and contemporary responses to refugee crises today?

Identify continuities and changes in institutional responses, public attitudes, and media portrayals of forced migration.

Exercise 5.4

These assignments are designed to help you engage more deeply with the themes, sources, and analytical frameworks of the unit. They combine historical analysis with creative and critical thinking skills, and can be adapted for classroom discussion, written work, or group projects.

1. Primary Source Analysis

Assignment: Analyze selections from relief committee reports or testimonies of Jewish migrants related to the Galician refugee crisis (see reading list).

Instructions:

- Identify the author, intended audience, and purpose of the document.

- Analyze how refugees are described (in terms of terminology, tone, and perceived needs).

- Consider how the document reflects broader political or social attitudes toward migration.

Learning Outcome: Develop source analysis skills; understand how language shapes humanitarian narratives.

2. Comparative Essay

Assignment: Write an essay comparing the 1881–1882 Jewish refugee crisis in Galicia with another historical displacement event (e.g., the Armenian exodus from the Ottoman Empire, Russian Civil War refugees, or Syrian displacement today).

Instructions:

- Compare causes, responses, and outcomes.

- Use Gatrell’s framework[10] to analyze how refugeedom was constructed in both cases.

- Reflect on how the historical context shaped legal and humanitarian responses.

Learning Outcome: Apply comparative analysis to forced migration; connect historical and contemporary refugee studies.

3. Migration Mapping Activity

Assignment: Create a visual map tracing refugee routes from pogrom-affected regions of the Russian Empire to Galicia and beyond, including destinations such as Hamburg, New York, and Paris.

Instructions:

- Utilize historical data and digital mapping tools, or hand-drawn maps.

- Mark key border towns (Brody, Lviv), transit zones, and resettlement destinations.

- Add brief notes or symbols to indicate state responses or aid organizations.

Learning Outcome: Understand the spatial dimensions of refugee movement and visualize migration infrastructure.

You have now completed Section 3 of Unit 5. Up next is a collection of resources and additional readings for this unit.

- For more on history of border crisis, see Bӧrries Kuzmany, “Jüdische Pogromflüchtlinge in Österreich 1881/82 und die Professionalisierung der internationalen Hilfe,” in Aufnahmeland Österreich, eds. B. Kuzmany and R. Garstenauer (Wien: New Academic Press, 2017), 94–125; Benyamin Lukin, Olga Shraberman, “Documents on the Emigration of Russian Jews via Galicia, 1881–82, in the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem,” in: Gal-Ed. On the history of the Jews in Poland. (2007), 101–117; Tobias Brinkmann, Between Borders: The Great Jewish Migration from Eastern Europe (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024), 31–50; Oleksii Chebotarov, Jews from the East, Global Migration, and Habsburg Galicia in the Early 1880s (PhD diss., University of St. Gallen, 2021) ↵

- Oleksii Chebotarov, Jews from the East, Global Migration, and Habsburg Galicia in the Early 1880s, 60-74. ↵

- Ibid, 65-74. ↵

- Tobias Brinkmann, Between Borders: The Great Jewish Migration from Eastern Europe (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024), 31–50 ↵

- Oleksii Chebotarov, Jews from the East, Global Migration, and Habsburg Galicia in the Early 1880s, 80-82; Bӧrries Kuzmany, Jüdische Pogromflüchtlinge in Österreich 1881/82 und die Professionalisierung der internationalen Hilfe, 104-108. ↵

- Goldenstein, Leo. Brody und die russisch-jüdische Emigration. Nach eigener Beobachtung erzählt. Frankfurt am Main, 1882, p. 20-29. ↵

- Oleksii Chebotarov, Jews from the East, Global Migration, and Habsburg Galicia in the Early 1880s, 83-105 ↵

- Ibid, 109-121 ↵

- Ibid, 100-106 ↵

- Gatrell, Peter. “Refugees – What’s Wrong with History?” Journal of Refugee Studies 30, no. 2 (2017): 170–189 ↵