Unit 6: Nationalizing the Landscape

Section 3: Case studies

Before we look at two case studies, here is a summary of the historical background you will need to understand the cases in question:

3.1 What is meant by the ‘nationalizing state’?

Interwar Poland is often described as a ‘nationalizing state’.

Roger Brubaker defines this as a state in which national unity was still in the making (Brubaker 1996).

What were the consequences of this?

- The newly established Polish state incorporated regions with very different histories, previously under different empires.

- The new borders did not coincide seamlessly with pre-existing territories.

- The country included significant national minorities, particularly Ukrainians and Jews. The minority issue was complex and difficult to resolve.

- Uniting the newly acquired territories into a cohesive state required fostering a common national consciousness, achieved through language, culture, and symbols that were familiar and accessible to all citizens.

- The development of the tourist industry served the purpose of nationalization and inscription of the borderlands on the mental map, presenting them as ethnically and culturally ‘Polish’.

Example

The historian of interwar Poland, Jagoda Wierzejska, describes this process in detail through the ‘exploration’ of the Eastern Carpathians by Polish organizations such as the Polska Liga Turystyki.

The exoticization of the mountains served not only to transform the region into a popular tourist destination, but also to integrate it into Poland’s mental geography (Wierzejska 2021).

3.2 How did the development of Polish tourism serve ‘nationalization’?

Tourism in interwar Poland developed rapidly precisely during the period of ‘nationalization’, especially in the 1930s.

Key dates in the development of Polish tourism:

- In the 1920s: pre-war tourist societies such as the Polish Tatra Society (Polskie Towarzystwo Tatrzańskie) and the Polish Tourist Society (Polskie Towarzystwo Krajoznawcze) were primarily responsible for organizing travel under the supervision of the Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych (Ministry of Public Works).

- In the late 1920s: the Polish state took a more active role in the development of tourism.

- 1932: the Ministry of Communications (Ministerstwo Komunikacji) assumed control of the sector, reflecting its growing importance.

- By 1935: dozens of societies and tourist clubs had emerged, promoting tourism on a large scale (Gawkowski 2011).

- 1935: the League for the Promotion of Tourism (Liga Popierania Turystyki) was established to further popularize and support travel. Infrastructure was adapted to accommodate tourists, with new routes opening and train ticket discounts introduced to encourage domestic travel. Buses and airplanes also became increasingly available, expanding access to remote locations.

- 1930s: the tourism industry saw the publication of specialized journals and newspapers, such as Turysta w Polsce (1935–1938) and Wiadomości Turystyczne (1931–1939), which provided information on travel opportunities and encouraged tourism among the middle class (Tałuć 2021).

- By the mid-1930s, tourism had transformed from an elite leisure activity into a mass phenomenon.

- 1935: the Central Vacation Bureau (Centralne Biuro Wczasów), established in 1935, played a key role in this transformation. With the support of the state and insurance companies such as Zakład Ubezpieczeń Społecznych, the bureau helped finance and organize vacations for workers, making travel more accessible to broader segments of society (Gawkowski 2011).

Despite these developments, Jewish and Ukrainian communities were largely excluded from the official tourism discourse.

While these minorities could theoretically participate in travel organizations, their presence was rarely reflected in tourist brochures, guided tours, or state-sponsored initiatives.

This exclusion further reinforced the perception of tourism as a nationalizing practice, designed primarily for ethnic Poles.

3.3: Case studies: introduction and outline

Case 1: Zalishchyky (Zaleszczyki)

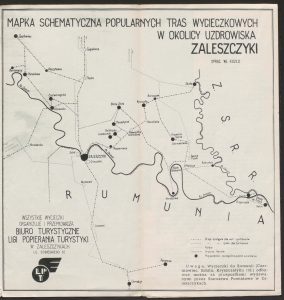

The first case is the promotion of tourism as a vehicle for national construction in interwar Poland, using the example of the border town of Zalishchyky (Zaleszczyki) in former Galicia.

During the interwar period, it became a popular resort and wine-producing center, attracting numerous visitors.

However, the guidebooks attempted to present Zalishchyky as a brand-new place, ignoring the presence of the Ukrainian and Jewish populations as well as the detrimental influence of the new border on the economy.

The case of Zalishchyky shows how the creation of tourist infrastructure in interwar Poland erased the past history of the area and replaced it with the modern idea of a resort, strongly linked to the national image.

Tourist brochures, images, and photographs reflect this attitude. The analysis of these documents in comparison with the other testimonies makes us think about how the narrative is constructed.

Case 2: Landkentenish

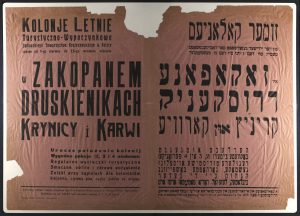

The second case study deals with the emerging Jewish interwar tourist movement ‘Krajoznawstwo/Landkentenish’.

This appeared in response to the exclusion of the Jewish minority from national Polish tourist practice and encouraged Jews to find their own connection to the country through travel.

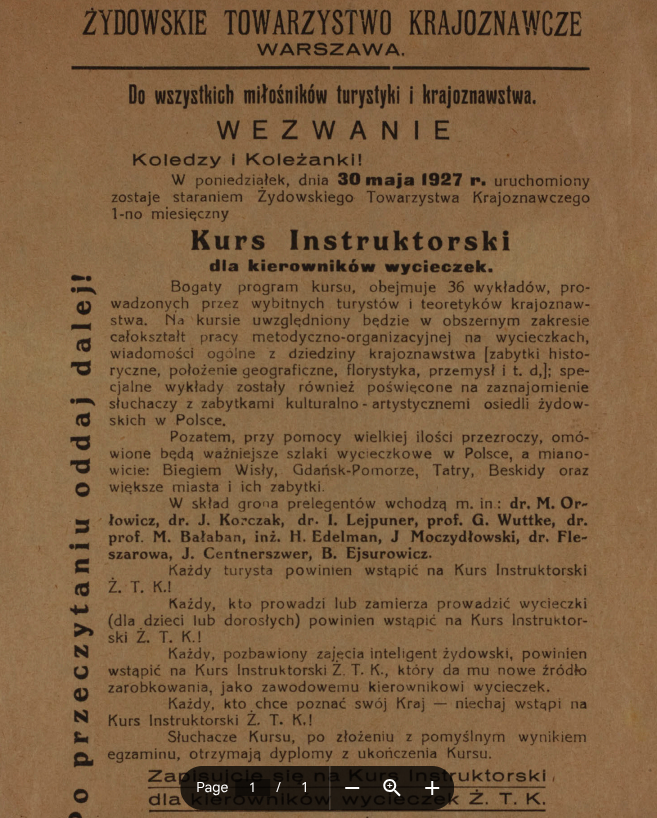

Żydowskie Towarzystwo Krajoznawcze (ŻTK) – the Jewish Krajoznawstwo Society was founded in 1926 as an attempt to fill a gap for Jews who wanted to explore the country in a touristic way, but did not feel welcome in Polish or Ukrainian tourist organizations.

The organization established branches in large cities such as Vilnius, Lodz or Lviv and by 1936 it had over 4,000 members. It organized tourist hostels in various places, including the Eastern Carpathians, e.g., Yaremche, Vorokhta, Zalishchyky.

The Polish interwar movement of the Jewish Touring Society published its own Yiddish-Polish newspaper, Landkentenish-Krajoznawstwo (Knowledge of the Land). In it they published reports, explained the idea of the movement, and various authors described interesting tourist destinations connected with Jewish history or culture, as well as generally popular tourist locations, such as the lakes or mountains (Borzymińska).

The Society’s mission was to familiarize people with the Polish land in order to become true citizens.

The movement not only focused on Jewish landmarks but also encouraged Jews to explore the country’s nature and folk culture.

3.4 Case study 1: Zalishchyky

Zalishchyky, a town in southern Galicia, was an important trading center before World War I and a border town with Romania after the war. In the Habsburg period in 1890, it had a predominantly Jewish population:

- 4,513 Jews (78.5%),

- 712 Roman Catholics (12.4%)

- 481 Greek Catholics (8.4%) (Słownik geograficzny, 1895).

Many Jewish merchants were involved in the wine trade with the neighboring Romanian towns, connected by business and family ties.

After the war, the Jewish population decreased both in number and percentage, although it remained the largest group. In 1921 there were:

- 2,485 Jews (60.5%),

- 971 Roman Catholics (23.7%)

- 537 Greek Catholics (13.1%) (Skorowidz miejscowości, 1923).

The change of borders in 1919 altered the area and made Zalishchyky a border town of the Second Polish Republic.

The economy was ruined by the war and then transformed by the border changes.

The possibilities of traveling across the newly established border with Romania were limited, and the wine merchants had to undergo economic hardships.

This situation is described in the 1928 travelogue of the Warsaw Yiddish writer Yoel Mastboym, who visited Zalishchyky and spoke with local Jews who had been separated from their families and trade routes by the border changes (Mastboym, 1929).

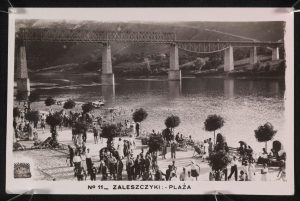

The official Polish narrative of the interwar period portrayed Zalishchyky as a successful resort, with modern buildings, comfortable infrastructure, spacious beaches, and crowds of visitors. There was no mention of the wartime destruction that left the town in ruins, nor of the population decline.

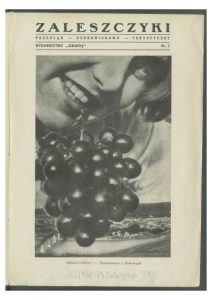

The tourist brochures promoted the town as one of the sunniest parts of the Second Polish Republic, explaining how the unique climate allowed the growth of such, for Galicia, exotic fruits as apricots and peaches. The brochures even compared it to North African climatic stations, California and Miami, using famous vacation spots abroad as the marketing tool.

Ironically, the comparison with non-Polish places was the most popular feature of Zalishchyky’s marketing (Gawkowski 2011; Zaleszczyki: Przegląd uzdrowiskowo, 1933).

The English traveler Bernard Newman remembers how he was advised to visit Zalishchyky because it reminded him of Italy and was “the least Polish” of all locations (Newman 1935).

The beaches near the Dnister River were organized in a modern way, including the nudist beach.

Another speciality of the area was winemaking and the big wine festival in September, called ‘The Feast of Polish Wine’ (Gawkowski 2011).

The target audience for this tourist destination came mainly from Warsaw: ‘Columbus discovered America! Warsaw discovered Zaleszczyki’ (Zaleszczyki: Przegląd uzdrowiskowo, 1933).

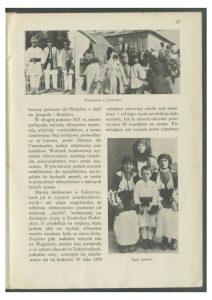

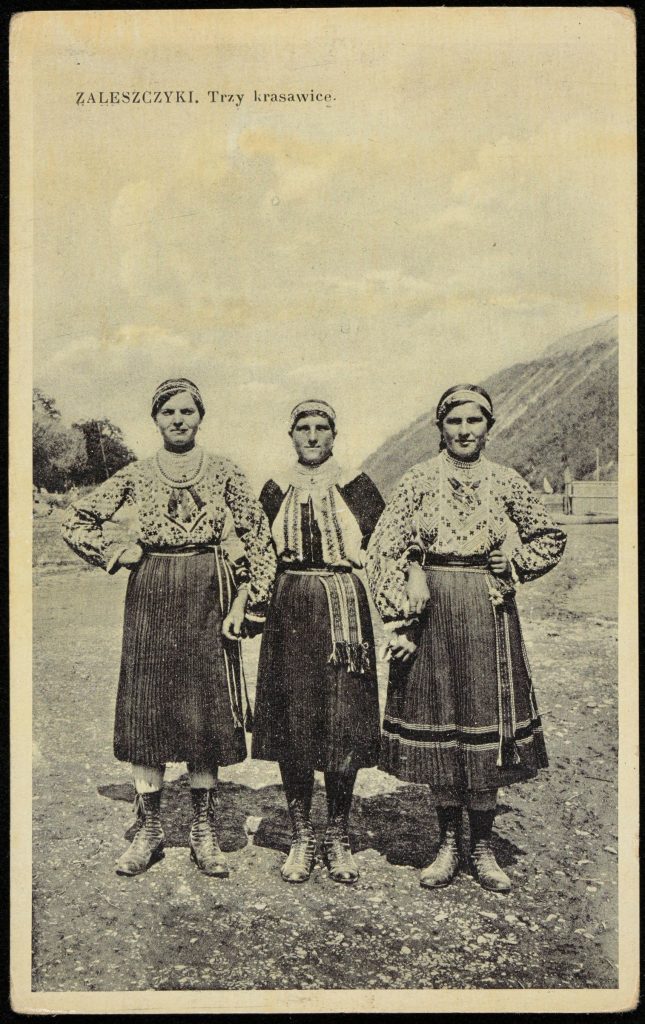

This slogan, as well as a few other elements in the tourist brochures, such as the photographs of locals in picturesque folk costumes and the juxtaposition of old, undeveloped Zaleszczyki with modern and civilized Zaleszczyki under the management of the Polish state, are reminiscent of the paternalistic and exoticizing approach of empires to their colonies.

The tourist gaze, shaped by guidebooks, directed the attention of visitors.

These narratives ignored the fact that the change in borders dramatically altered the relationships in the area.

Although the region had a long history of wine trade, the author of one of the pamphlets intended to promote wine production calling it “local and amateur” in the Habsburg period and predicted great opportunities for the industry in the Polish state because of the “direction of self-sufficiency” (kierunek samowystarczalności) in the state economy.

The tourist discourse, as reflected in the brochures of the League for the Promotion of Tourism, ignored the substantial ethnic groups: Poles and Ukrainians.

Ukrainians appear in postcard-like pictures with the caption “typy ludowe” (“ethnic types”). The Zalishchyky, represented in the guidebooks, seemed like a place created mostly from scratch.

The modern tourist industry was juxtaposed with the ethnicized traditional local population.

Exercise 6.5

Look at the article Gorąco! Gorąco! Gorąco! (English translation) in Zaleszczyki : przegląd uzdrowiskowo-turystyczny. 1933. nr 1, pp. 12-14 .

Now answer the following questions:

- How can you apply the concept of ‘tourist gaze’ to the new industry developed in Zalishchyky?

- Examine the visual materials advertising the tourist opportunities in Zalishchyky. What image do they convey? What is not shown in the images?

- Analyze the excerpt from the brochure and the fragment from the Yiddish travelogue. How do they represent the city?

- How is Zalishchyky located in the imaginary geography of the visitors?

3.5 Case study 2: Landkentenish – minority tourism in the national state

The idea of traveling to get to know the country was common in the national tourism of the interwar period.

What was new for the Landkentenish/Krajoznawstwo movement was that it came not from the state, but from a minority.

The Jews in interwar Poland were diverse in their ideological views. While the Zionist movement encouraged emigration to Palestine, the other options included integration into Polish society.

The historian Kenneth Moss, in his research on interwar Polish Jewry, noted that the interest of Polish Jews in tourism was a way to escape the growing hostility of the surrounding society and to find political refuge. He notes that in the late 1930s, when the number of Jews joining the ZTK (Żydowskie towarzystwo krajoznawcze) increased rapidly (Moss, 2021).

The newspaper Landkentnish/Krajoznawstwo represents the diasporic approach to Jewish politics in the interwar period, namely, the idea that it is possible to stay in the country.

In order to live in society, it was argued, Jews had to know the surrounding country, including its Jewish and non-Jewish places.

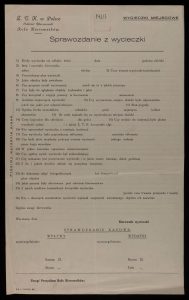

Different branches of the society had different directions of travel, which included photographic trips, hiking, traveling by car, winter sports, etc. The tourists could also participate in the documentation of the heritage, by photographing different sites and were trained in this (Pasternak and Zietkewicz 2019).

The organization of colonies was one of the most popular retreats, which could last several months and gather hundreds of people.

The most important destinations were places associated with nature, such as the Carpathians. This was connected with the need to take Jews out of the city and emphasize their rootedness in the land and nature.

Example

In 1933, the Lviv branch of the Society organized 9 trips to the mountains (20 people each), 22 trips to other places, and 8 industrial tours (Wiadomości ŻTK, 1933). The group would stay in one place, e.g. Yamna, and from there make excursions. In 1937, for example, the ‘colony’ lasted one and a half months, and more than 100 people participated. The one or two-day trips included the mountains, such as Howerla, Jaremcze waterfall, or a car trip to the Hutsul land (Jamna, Dilok, Mikuliczyn, etc.). The purpose of the trip was “rest for the working intelligentsia and getting to know the beautiful surroundings of the city” (Wiadomości ŻTK, 1937).

If we take a closer look at the itineraries in the Carpathians, there are no specific ‘Jewish places’. Most of the destinations were part of Polish or Ukrainian travel guides.

The idea of getting to know one’s own country included not only trips of physical activity, but also artistic reflections.

The newspaper Landkentenish published poems or essays by Jewish writers, such as Israel Ashendorf’s essay on the waterfall in Yaremche or Rokhl Korn’s poem on the mountain shepherds. The texts were usually accompanied by photographs of the place (Wiadomości ŻTK, 1937).

In Ashendorf’s poetic essay, man is inspired by the waterfall, which moves and remains in place at the same time; this sensitivity to nature and the motifs of the villages was part of the program of the movement, which aimed to reconnect Jews with nature (Moss 2021).

The unproductive life of the Jews in the cities was one of the problems that alienated them from society. Thus, tourism took on the political goal of reconnecting with nature, which was supposed to have a positive influence on the status of Jews in society.

Review Exercises

We have now come to the end of the final section in the unit. Complete the following exercise based on what you have learned.

Exercise 6.6

Look at the following material:

- Statut Żydowskiego Towarzystwa Krajoznawczego w Polsce. Warszawa, 1927, pp. 2-4.

- Fragment from the newspaper Landkentnish/Krajoznawstwo E.g., the issue dedicated to Lviv and Carpathians.

Examine the issue of the newspaper Landkentnish/Krajoznawstwo, dedicated to Lviv. What kind of landmarks do they choose to promote ‘familiarization with the land’?

Look over Case Study 2 and answer the following questions:

- How is the ‘tourist gaze’ of Jewish tourists shaped by societal conditions?

- Examine materials advertising tourist opportunities for Jews in interwar Poland. What kind of ‘familiarization with the land’ do they promote?

- Analyze the statute of the Jewish Tourist Society. What are its aims? How do they reflect the position of Jews in Polish society?

Exercise 6.7

Choose one of the following examples of tourist industries that have developed in East-Central Europe in recent decades. Access the sites given for information:

- Holocaust-themed tourism in Poland: Auschwitz tours from Kraków

- Soviet nostalgia tourism in Poland, Germany, and Ukraine

- Tourism to Chernobyl in Ukraine

Analyze the advertising strategies used by tour agencies, guidebooks, and the reviews and blogs of those who have participated in these tours.

Consider the following questions:

- Who founded the companies providing these tours?

- When did they emerge?

- Are they locally based or foreign owned?

- What kind of ‘gaze’ or ‘glance’ do these industries represent?

- Are these tours marketed as elite or mass tourism?

- How do they construct historical narratives?

Exercise 6.8

Design your own tour. Develop an itinerary and a historical narrative for the tour. Consider how you would market it and what perspective you would emphasize.

You have now completed Section 3 of Unit 6. Up next is a collection of resources and additional readings for this unit. See Module 2: Additional Readings for the full bibliography for Unit 6.