Abandoned Packard Automotive Plant in Detroit, Michigan. Wikimedia.

I. Introduction

On December 6, 1969, an estimated three hundred thousand people converged on the Altamont Motor Speedway in Northern California for a massive free concert headlined by the Rolling Stones and featuring some of the era’s other great rock acts.1 Only four months earlier, Woodstock had shown the world the power of peace and love and American youth. Altamont was supposed to be “Woodstock West.”2

But Altamont was a disorganized disaster. Inadequate sanitation, a horrid sound system, and tainted drugs strained concertgoers. To save money, the Hells Angels biker gang was paid $500 in beer to be the show’s “security team.” The crowd grew progressively angrier throughout the day. Fights broke out. Tensions rose. The Angels, drunk and high, armed themselves with sawed-off pool cues and indiscriminately beat concertgoers who tried to come on the stage. The Grateful Dead refused to play. Finally, the Stones came on stage.3

The crowd’s anger was palpable. Fights continued near the stage. Mick Jagger stopped in the middle of playing “Sympathy for the Devil” to try to calm the crowd: “Everybody be cool now, c’mon,” he pleaded. Then, a few songs later, in the middle of “Under My Thumb,” eighteen-year-old Meredith Hunter approached the stage and was beaten back. Pissed off and high on methamphetamines, Hunter brandished a pistol, charged again, and was stabbed and killed by an Angel. His lifeless body was stomped into the ground. The Stones just kept playing.4

If the more famous Woodstock music festival captured the idyll of the sixties youth culture, Altamont revealed its dark side. There, drugs, music, and youth were associated not with peace and love but with anger, violence, and death. While many Americans in the 1970s continued to celebrate the political and cultural achievements of the previous decade, a more anxious, conservative mood grew across the nation. For some, the United States had not gone nearly far enough to promote greater social equality; for others, the nation had gone too far, unfairly trampling the rights of one group to promote the selfish needs of another. Onto these brewing dissatisfactions, the 1970s dumped the divisive remnants of a failed war, the country’s greatest political scandal, and an intractable economic crisis. It seemed as if the nation was ready to unravel.

II. The Strain of Vietnam

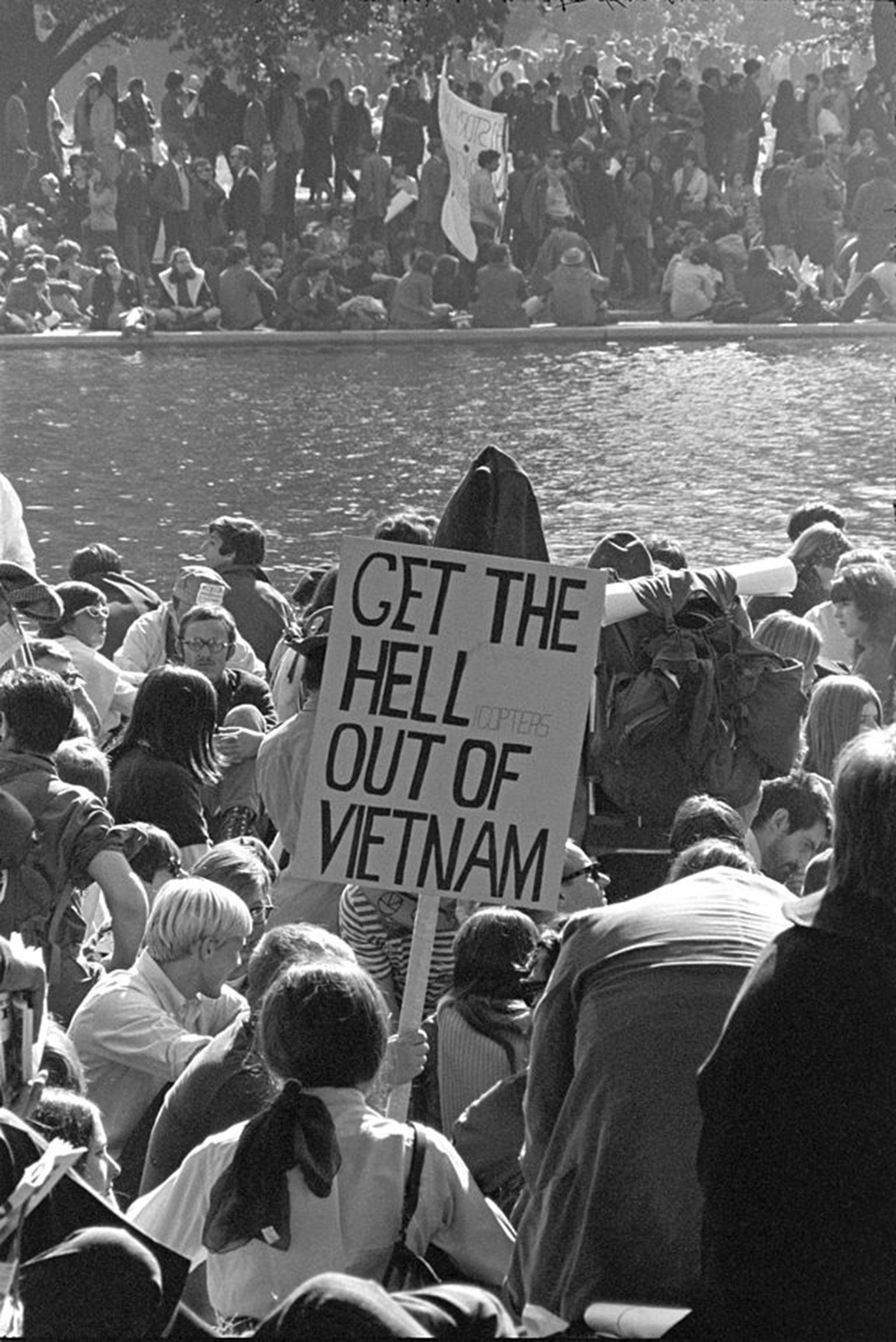

Vietnam War protestors at the March on the Pentagon. Lyndon B. Johnson Library via Wikimedia.

Perhaps no single issue contributed more to public disillusionment than the Vietnam War. As the war deteriorated, the Johnson administration escalated American involvement by deploying hundreds of thousands of troops to prevent the communist takeover of the south. Stalemates, body counts, hazy war aims, and the draft catalyzed an antiwar movement and triggered protests throughout the United States and Europe. With no end in sight, protesters burned draft cards, refused to pay income taxes, occupied government buildings, and delayed trains loaded with war materials. By 1967, antiwar demonstrations were drawing hundreds of thousands. In one protest, hundreds were arrested after surrounding the Pentagon.5

Vietnam was the first “living room war.”6 Television, print media, and open access to the battlefield provided unprecedented coverage of the conflict’s brutality. Americans confronted grisly images of casualties and atrocities. In 1965, CBS Evening News aired a segment in which U.S. Marines burned the South Vietnamese village of Cam Ne with little apparent regard for the lives of its occupants, who had been accused of aiding Vietcong guerrillas. President Johnson berated the head of CBS, yelling over the phone, “Your boys just shat on the American flag.”7

While the U.S. government imposed no formal censorship on the press during Vietnam, the White House and military nevertheless used press briefings and interviews to paint a deceptive image of the war. The United States was winning the war, officials claimed. They cited numbers of enemies killed, villages secured, and South Vietnamese troops trained. However, American journalists in Vietnam quickly realized the hollowness of such claims (the press referred to afternoon press briefings in Saigon as “the Five o’Clock Follies”).8 Editors frequently toned down their reporters’ pessimism, often citing conflicting information received from their own sources, who were typically government officials. But the evidence of a stalemate mounted.

Stories like CBS’s Cam Ne piece exposed a credibility gap, the yawning chasm between the claims of official sources and the increasingly evident reality on the ground in Vietnam.9 Nothing did more to expose this gap than the 1968 Tet Offensive. In January, communist forces attacked more than one hundred American and South Vietnamese sites throughout South Vietnam, including the American embassy in Saigon. While U.S. forces repulsed the attack and inflicted heavy casualties on the Vietcong, Tet demonstrated that despite the repeated claims of administration officials, the enemy could still strike at will anywhere in the country, even after years of war. Subsequent stories and images eroded public trust even further. In 1969, investigative reporter Seymour Hersh revealed that U.S. troops had raped and/or massacred hundreds of civilians in the village of My Lai.10 Three years later, Americans cringed at Nick Ut’s wrenching photograph of a naked Vietnamese child fleeing a South Vietnamese napalm attack. More and more American voices came out against the war.

Reeling from the war’s growing unpopularity, on March 31, 1968, President Johnson announced on national television that he would not seek reelection.11 Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy unsuccessfully battled against Johnson’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey, for the Democratic Party nomination (Kennedy was assassinated in June). At the Democratic Party’s national convention in Chicago, local police brutally assaulted protesters on national television.

For many Americans, the violent clashes outside the convention hall reinforced their belief that civil society was unraveling. Republican challenger Richard Nixon played on these fears, running on a platform of “law and order” and a vague plan to end the war. Well aware of domestic pressure to wind down the war, Nixon sought, on the one hand, to appease antiwar sentiment by promising to phase out the draft, train South Vietnamese forces to assume more responsibility for the war effort, and gradually withdraw American troops. Nixon and his advisors called it “Vietnamization.”12 At the same time, Nixon appealed to the so-called silent majority of Americans who still supported the war (and opposed the antiwar movement) by calling for an “honorable” end to U.S. involvement—what he later called “peace with honor.”13 He narrowly edged out Humphrey in the fall’s election.

Public assurances of American withdrawal, however, masked a dramatic escalation of conflict. Looking to incentivize peace talks, Nixon pursued a “madman strategy” of attacking communist supply lines across Laos and Cambodia, hoping to convince the North Vietnamese that he would do anything to stop the war.14 Conducted without public knowledge or congressional approval, the bombings failed to spur the peace process, and talks stalled before the American-imposed November 1969 deadline. News of the attacks renewed antiwar demonstrations. Police and National Guard troops killed six students in separate protests at Jackson State University in Mississippi, and, more famously, Kent State University in Ohio in 1970.

Another three years passed—and another twenty thousand American troops died—before an agreement was reached.15 After Nixon threatened to withdraw all aid and guaranteed to enforce a treaty militarily, the North and South Vietnamese governments signed the Paris Peace Accords in January 1973, marking the official end of U.S. force commitment to the Vietnam War. Peace was tenuous, and when war resumed North Vietnamese troops quickly overwhelmed southern forces. By 1975, despite nearly a decade of direct American military engagement, Vietnam was united under a communist government.

The Vietnam War profoundly influenced domestic politics. Moreover, it poisoned many Americans’ perceptions of their government and its role in the world. And yet, while the antiwar demonstrations attracted considerable media attention and stand today as a hallmark of the sixties counterculture, many Americans nevertheless continued to regard the war as just. Wary of the rapid social changes that reshaped American society in the 1960s and worried that antiwar protests threatened an already tenuous civil order, a growing number of Americans turned to conservatism.

III. Racial, Social, and Cultural Anxieties

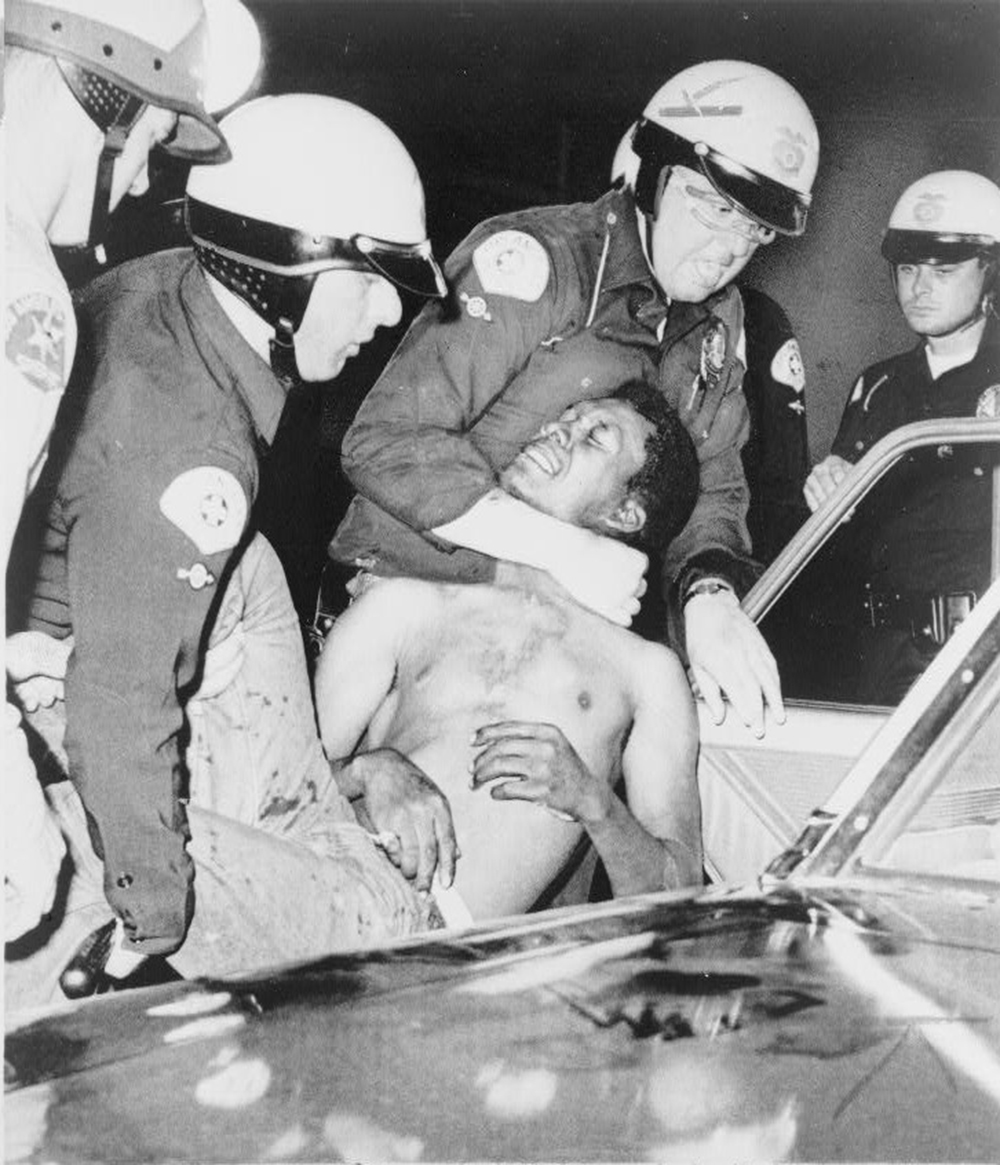

Los Angeles police violently arrest a man during the Watts riot on August 12, 1965. Wikimedia.

The civil rights movement looked dramatically different at the end of the 1960s than it had at the beginning. The movement had never been monolithic, but prominent, competing ideologies had fractured the movement in the 1970s. The rise of the Black Power movement challenged the integrationist dreams of many older activists as the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X fueled disillusionment and many alienated activists recoiled from liberal reformers.

The political evolution of the civil rights movement was reflected in American culture. The lines of race, class, and gender ruptured American “mass” culture. The monolith of popular American culture, pilloried in the fifties and sixties as exclusively white, male-dominated, conservative, and stifling, finally shattered and Americans retreated into ever smaller, segmented subcultures. Marketers now targeted particular products to ever smaller pieces of the population, including previously neglected groups such as African Americans.16 Subcultures often revolved around certain musical styles, whether pop, disco, hard rock, punk rock, country, or hip-hop. Styles of dress and physical appearance likewise aligned with cultures of choice.

If the popular rock acts of the sixties appealed to a new counterculture, the seventies witnessed the resurgence of cultural forms that appealed to a white working class confronting the social and political upheavals of the 1960s. Country hits such as Merle Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee” evoked simpler times and places where people “still wave Old Glory down at the courthouse” and they “don’t let our hair grow long and shaggy like the hippies out in San Francisco.” (Haggard would claim the song was satirical, but it nevertheless took hold.) A popular television sitcom, All in the Family, became an unexpected hit among “middle America.” The show’s main character, Archie Bunker, was designed to mock reactionary middle-aged white men, but audiences embraced him. “Isn’t anyone interested in upholding standards?” he lamented in an episode dealing with housing integration. “Our world is coming crumbling down. The coons are coming!”17

The cast of CBS’s All in the Family in 1973. Wikimedia.

As Bunker knew, African Americans were becoming much more visible in American culture. While Black cultural forms had been prominent throughout American history, they assumed new popular forms in the 1970s. Disco offered a new, optimistic, racially integrated pop music. Musicians such as Aretha Franklin, Andraé Crouch, and “fifth Beatle” Billy Preston brought their background in church performance to their own recordings as well as to the work of white artists like the Rolling Stones, with whom they collaborated. By the end of the decade, African American musical artists had introduced American society to one of the most significant musical innovations in decades: the Sugarhill Gang’s 1979 record, Rapper’s Delight. A lengthy paean to Black machismo, it became the first rap single to reach the Top 40.18

Just as rap represented a hypermasculine Black cultural form, Hollywood popularized its white equivalent. Films such as 1971’s Dirty Harry captured a darker side of the national mood. Clint Eastwood’s titular character exacted violent justice on clear villains, working within the sort of brutally simplistic ethical standard that appealed to Americans anxious about a perceived breakdown in “law and order.” (“The film’s moral position is fascist,” said critic Roger Ebert, who nevertheless gave it three out of four stars.19)

Perhaps the strongest element fueling American anxiety over “law and order” was the increasingly visible violence associated with the civil rights movement. No longer confined to the antiblack terrorism that struck the southern civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, publicly visible violence now broke out among Black Americans in urban riots and among whites protesting new civil rights programs. In the mid-1970s, for instance, protests over the use of busing to overcome residential segregation and truly integrate public schools in Boston washed the city in racial violence. Stanley Forman’s Pulitzer Prize–winning photo, The Soiling of Old Glory, famously captured a Black civil rights attorney, Ted Landsmark, being attacked by a mob of anti-busing protesters, one of whom wielded an American flag as a weapon.20

Urban riots, though, rather than anti-integration violence, tainted many white Americans’ perception of the civil rights movement and urban life in general. Civil unrest broke out across the country, but the riots in Watts/Los Angeles (1965), Newark (1967), and Detroit (1967) were the most shocking. In each, a physical altercation between white police officers and African Americans spiraled into days of chaos and destruction. Tens of thousands participated in urban riots. Many looted and destroyed white-owned business. There were dozens of deaths, tens of millions of dollars in property damage, and an exodus of white capital that only further isolated urban poverty.21

In 1967, President Johnson appointed the Kerner Commission to investigate the causes of America’s riots. Their report became an unexpected best seller.22 The commission cited Black frustration with the hopelessness of poverty as the underlying cause of urban unrest. As the head of the Black National Business League testified, “It is to be more than naïve—indeed, it is a little short of sheer madness—for anyone to expect the very poorest of the American poor to remain docile and content in their poverty when television constantly and eternally dangles the opulence of our affluent society before their hungry eyes.”23 A Newark rioter who looted several boxes of shirts and shoes put it more simply: “They tell us about that pie in the sky but that pie in the sky is too damn high.”24 But white conservatives blasted the conclusion that white racism and economic hopelessness were to blame for the violence. African Americans wantonly destroying private property, they said, was not a symptom of America’s intractable racial inequalities but the logical outcome of a liberal culture of permissiveness that tolerated—even encouraged—nihilistic civil disobedience. Many white moderates and liberals, meanwhile, saw the explosive violence as a sign that African Americans had rejected the nonviolence of the earlier civil rights movement.

The unrest of the late sixties did, in fact, reflect a real and growing disillusionment among African Americans with the fate of the civil rights crusade. In the still-moldering ashes of Jim Crow, African Americans in Watts and other communities across the country bore the burdens of lifetimes of legally sanctioned discrimination in housing, employment, and credit. Segregation survived the legal dismantling of Jim Crow. The perseverance into the present day of stark racial and economic segregation in nearly all American cities destroyed any simple distinction between southern de jure segregation and nonsouthern de facto segregation. Black neighborhoods became traps that too few could escape.

Political achievements such as the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act were indispensable legal preconditions for social and political equality, but for most, the movement’s long (and now often forgotten) goal of economic justice proved as elusive as ever. “I worked to get these people the right to eat cheeseburgers,” Martin Luther King Jr. supposedly said to Bayard Rustin as they toured the devastation in Watts some years earlier, “and now I’ve got to do something . . . to help them get the money to buy it.”25 What good was the right to enter a store without money for purchases?

IV. The Crisis of 1968

To Americans in 1968, the country seemed to be unraveling. Martin Luther King Jr. was killed on April 4, 1968. He had been in Memphis to support striking sanitation workers. (Prophetically, he had reflected on his own mortality in a rally the night before. Confident that the civil rights movement would succeed without him, he brushed away fears of death. “I’ve been to the mountaintop,” he said, “and I’ve seen the promised land.”). The greatest leader in the American civil rights movement was lost. Riots broke out in over a hundred American cities. Two months later, on June 6, Robert F. Kennedy was killed campaigning in California. He had represented the last hope of liberal idealists. Anger and disillusionment washed over the country.

As the Vietnam War descended ever deeper into a brutal stalemate and the Tet Offensive exposed the lies of the Johnson administration, students shut down college campuses and government facilities. Protests enveloped the nation.

Protesters converged on the Democratic National Convention in Chicago at the end of August 1968, when a bitterly fractured Democratic Party gathered to assemble a passable platform and nominate a broadly acceptable presidential candidate. Demonstrators planned massive protests in Chicago’s public spaces. Initial protests were peaceful, but the situation quickly soured as police issued stern threats and young people began to taunt and goad officials. Many of the assembled students had protest and sit-in experiences only in the relative safe havens of college campuses and were unprepared for Mayor Richard Daley’s aggressive and heavily armed police force and National Guard troops in full riot gear. Attendees recounted vicious beatings at the hands of police and Guardsmen, but many young people—convinced that much public sympathy could be won via images of brutality against unarmed protesters—continued stoking the violence. Clashes spilled from the parks into city streets, and eventually the smell of tear gas penetrated the upper floors of the opulent hotels hosting Democratic delegates. Chicago’s brutality overshadowed the convention and culminated in an internationally televised, violent standoff in front of the Hilton Hotel. “The whole world is watching,” the protesters chanted. The Chicago riots encapsulated the growing sense that chaos now governed American life.

For many sixties idealists, the violence of 1968 represented the death of a dream. Disorder and chaos overshadowed hope and progress. And for conservatives, it was confirmation of all of their fears and hesitations. Americans of 1968 turned their back on hope. They wanted peace. They wanted stability. They wanted “law and order.”

V. The Rise and Fall of Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon campaigns in Philadelphia during the 1968 presidential election. National Archives.

Beleaguered by an unpopular war, inflation, and domestic unrest, President Johnson opted against reelection in March 1968—an unprecedented move in modern American politics. The forthcoming presidential election was shaped by Vietnam and the aforementioned unrest as much as by the campaigns of Democratic nominee Vice President Hubert Humphrey, Republican Richard Nixon, and third-party challenger George Wallace, the infamous segregationist governor of Alabama. The Democratic Party was in disarray in the spring of 1968, when senators Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy challenged Johnson’s nomination and the president responded with his shocking announcement. Nixon’s candidacy was aided further by riots that broke out across the country after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the shock and dismay experienced after the slaying of Robert Kennedy in June. The Republican nominee’s campaign was defined by shrewd maintenance of his public appearances and a pledge to restore peace and prosperity to what he called “the silent center; the millions of people in the middle of the political spectrum.” This campaign for the “silent majority” was carefully calibrated to attract suburban Americans by linking liberals with violence and protest and rioting. Many embraced Nixon’s message; a September 1968 poll found that 80 percent of Americans believed public order had “broken down.”

Meanwhile, Humphrey struggled to distance himself from Johnson and maintain working-class support in northern cities, where voters were drawn to Wallace’s appeals for law and order and a rejection of civil rights. The vice president had a final surge in northern cities with the aid of union support, but it was not enough to best Nixon’s campaign. The final tally was close: Nixon won 43.3 percent of the popular vote (31,783,783), narrowly besting Humphrey’s 42.7 percent (31,266,006). Wallace, meanwhile, carried five states in the Deep South, and his 13.5 percent (9,906,473) of the popular vote constituted an impressive showing for a third-party candidate. The Electoral College vote was more decisive for Nixon; he earned 302 electoral votes, while Humphrey and Wallace received only 191 and 45 votes, respectively. Although Republicans won a few seats, Democrats retained control of both the House and Senate and made Nixon the first president in 120 years to enter office with the opposition party controlling both houses.

Once installed in the White House, Richard Nixon focused his energies on American foreign policy, publicly announcing the Nixon Doctrine in 1969. On the one hand, Nixon asserted the supremacy of American democratic capitalism and conceded that the United States would continue supporting its allies financially. However, he denounced previous administrations’ willingness to commit American forces to Third World conflicts and warned other states to assume responsibility for their own defense. He was turning America away from the policy of active, anticommunist containment, and toward a new strategy of détente.26

Promoted by national security advisor and eventual secretary of state Henry Kissinger, détente sought to stabilize the international system by thawing relations with Cold War rivals and bilaterally freezing arms levels. Taking advantage of tensions between communist China and the Soviet Union, Nixon pursued closer relations with both in order to de-escalate tensions and strengthen the United States’ position relative to each. The strategy seemed to work. In 1972, Nixon became the first American president to visit communist China and the first since Franklin Roosevelt to visit the Soviet Union. Direct diplomacy and cultural exchange programs with both countries grew and culminated with the formal normalization of U.S.-Chinese relations and the signing of two U.S.-Soviet arms agreements: the antiballistic missile (ABM) treaty and the Strategic Arms Limitations Treaty (SALT I). By 1973, after almost thirty years of Cold War tension, peaceful coexistence suddenly seemed possible.

Soon, though, a fragile calm gave way again to Cold War instability. In November 1973, Nixon appeared on television to inform Americans that energy had become “a serious national problem” and that the United States was “heading toward the most acute shortages of energy since World War II.”27 The previous month Arab members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), a cartel of the world’s leading oil producers, embargoed oil exports to the United States in retaliation for American intervention in the Middle East. The embargo launched the first U.S. energy crisis. By the end of 1973, the global price of oil had quadrupled.28 Drivers waited in line for hours to fill up their cars. Individual gas stations ran out of gas. American motorists worried that oil could run out at any moment. A Pennsylvania man died when his emergency stash of gasoline ignited in his trunk and backseat.29 OPEC rescinded its embargo in 1974, but the economic damage had been done. The crisis extended into the late 1970s.

Like the Vietnam War, the oil crisis showed that small countries could still hurt the United States. At a time of anxiety about the nation’s future, Vietnam and the energy crisis accelerated Americans’ disenchantment with the United States’ role in the world and the efficacy and quality of its leaders. Furthermore, government scandals in the 1970s and early 1980s sapped trust in America’s public institutions. In 1971, the Nixon administration tried unsuccessfully to sue the New York Times and the Washington Post to prevent the publication of the Pentagon Papers, a confidential and damning history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam commissioned by the Defense Department and later leaked. The papers showed how presidents from Truman to Johnson repeatedly deceived the public on the war’s scope and direction.30 Nixon faced a rising tide of congressional opposition to the war, and Congress asserted unprecedented oversight of American war spending. In 1973, it passed the War Powers Resolution, which dramatically reduced the president’s ability to wage war without congressional consent.

However, no scandal did more to unravel public trust than Watergate. On June 17, 1972, five men were arrested inside the offices of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) in the Watergate Complex in downtown Washington, D.C. After being tipped off by a security guard, police found the men attempting to install sophisticated bugging equipment. One of those arrested was a former CIA employee then working as a security aide for the Nixon administration’s Committee to Re-elect the President (lampooned as “CREEP”).

While there is no direct evidence that Nixon ordered the Watergate break-in, he had been recorded in conversation with his chief of staff requesting that the DNC chairman be illegally wiretapped to obtain the names of the committee’s financial supporters. The names could then be given to the Justice Department and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to conduct spurious investigations into their personal affairs. Nixon was also recorded ordering his chief of staff to break into the offices of the Brookings Institution and take files relating to the war in Vietnam, saying, “Goddammit, get in and get those files. Blow the safe and get it.”31

Whether or not the president ordered the Watergate break-in, the White House launched a massive cover-up. Administration officials ordered the CIA to halt the FBI investigation and paid hush money to the burglars and White House aides. Nixon distanced himself from the incident publicly and went on to win a landslide election victory in November 1972. But, thanks largely to two persistent journalists at the Washington Post, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, information continued to surface that tied the burglaries ever closer to the CIA, the FBI, and the White House. The Senate held televised hearings. Citing executive privilege, Nixon refused to comply with orders to produce tapes from the White House’s secret recording system. In July 1974, the House Judiciary Committee approved a bill to impeach the president. Nixon resigned before the full House could vote on impeachment. He became the first and only American president to resign from office.32

Vice President Gerald Ford was sworn in as his successor and a month later granted Nixon a full presidential pardon. Nixon disappeared from public life without ever publicly apologizing, accepting responsibility, or facing charges.

VI. Deindustrialization and the Rise of the Sunbelt

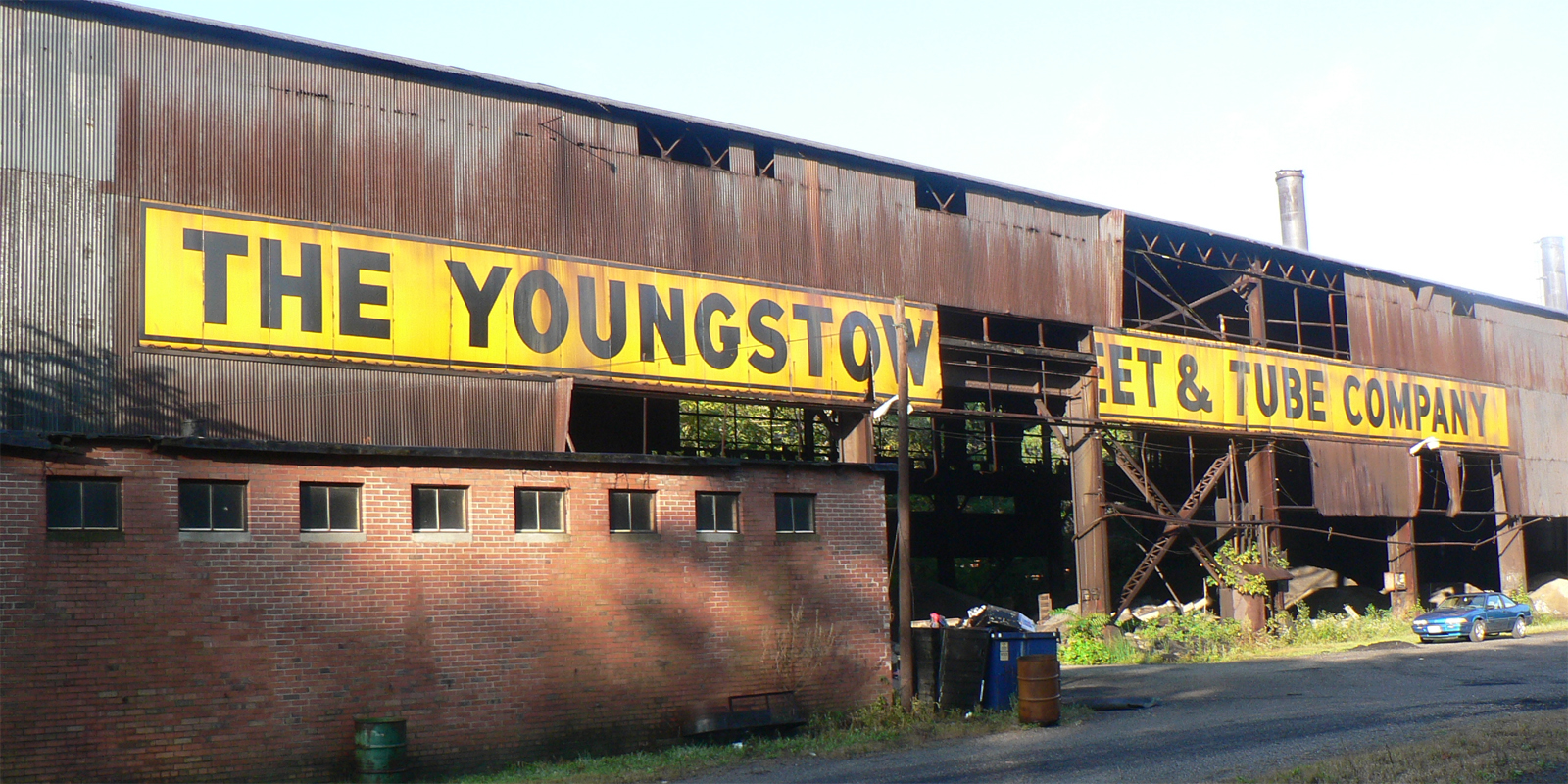

Abandoned Youngstown factory. Stuart Spivack, via Flickr.

American workers had made substantial material gains throughout the 1940s and 1950s. During the so-called Great Compression, Americans of all classes benefited from postwar prosperity. Segregation and discrimination perpetuated racial and gender inequalities, but unemployment continually fell and a highly progressive tax system and powerful unions lowered general income inequality as working-class standards of living nearly doubled between 1947 and 1973.

But general prosperity masked deeper vulnerabilities. Perhaps no case better illustrates the decline of American industry and the creation of an intractable urban crisis than Detroit. Detroit boomed during World War II. When auto manufacturers like Ford and General Motors converted their assembly lines to build machines for the American war effort, observers dubbed the city the “arsenal of democracy.”

After the war, however, automobile firms began closing urban factories and moving to outlying suburbs. Several factors fueled the process. Some cities partly deindustrialized themselves. Municipal governments in San Francisco, St. Louis, and Philadelphia banished light industry to make room for high-rise apartments and office buildings. Mechanization also contributed to the decline of American labor. A manager at a newly automated Ford engine plant in postwar Cleveland captured the interconnections between these concerns when he glibly noted to United Automobile Workers (UAW) president Walter Reuther, “You are going to have trouble collecting union dues from all of these machines.”33 More importantly, however, manufacturing firms sought to reduce labor costs by automating, downsizing, and relocating to areas with “business friendly” policies like low tax rates, anti-union right-to-work laws, and low wages.

Detroit began to bleed industrial jobs. Between 1950 and 1958, Chrysler, which actually kept more jobs in Detroit than either Ford or General Motors, cut its Detroit production workforce in half. In the years between 1953 and 1960, East Detroit lost ten plants and over seventy-one thousand jobs.34 Because Detroit was a single-industry city, decisions made by the Big Three automakers reverberated across the city’s industrial landscape. When auto companies mechanized or moved their operations, ancillary suppliers like machine tool companies were cut out of the supply chain and likewise forced to cut their own workforce. Between 1947 and 1977, the number of manufacturing firms in the city dropped from over three thousand to fewer than two thousand. The labor force was gutted. Manufacturing jobs fell from 338,400 to 153,000 over the same three decades.35

Industrial restructuring decimated all workers, but deindustrialization fell heaviest on the city’s African Americans. Although many middle-class Black Detroiters managed to move out of the city’s ghettos, by 1960, 19.7 percent of Black autoworkers in Detroit were unemployed, compared to just 5.8 percent of whites.36 Overt discrimination in housing and employment had for decades confined African Americans to segregated neighborhoods where they were forced to pay exorbitant rents for slum housing. Subject to residential intimidation and cut off from traditional sources of credit, few could afford to follow industry as it left the city for the suburbs and other parts of the country, especially the South. Segregation and discrimination kept them stuck where there were fewer and fewer jobs. Over time, Detroit devolved into a mass of unemployment, crime, and crippled municipal resources. When riots rocked Detroit in 1967, 25 to 30 percent of Black residents between ages eighteen and twenty-four were unemployed.37

Deindustrialization in Detroit and elsewhere also went hand in hand with the long assault on unionization that began in the aftermath of World War II. Lacking the political support they had enjoyed during the New Deal years, labor organizations such as the CIO and the UAW shifted tactics and accepted labor-management accords in which cooperation, not agitation, was the strategic objective.

This accord held mixed results for workers. On the one hand, management encouraged employee loyalty through privatized welfare systems that offered workers health benefits and pensions. Grievance arbitration and collective bargaining also provided workers official channels through which to criticize policies and push for better conditions. At the same time, bureaucracy and corruption increasingly weighed down unions and alienated them from workers and the general public. Union management came to hold primary influence in what was ostensibly a “pluralistic” power relationship. Workers—though still willing to protest—by necessity pursued a more moderate agenda compared to the union workers of the 1930s and 1940s. Conservative politicians meanwhile seized on popular suspicions of Big Labor, stepping up their criticism of union leadership and positioning themselves as workers’ true ally.

While conservative critiques of union centralization did much to undermine the labor movement, labor’s decline also coincided with ideological changes within American liberalism. Labor and its political concerns undergirded Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition, but by the 1960s, many liberals had forsaken working-class politics. More and more saw poverty as stemming not from structural flaws in the national economy, but from the failure of individuals to take full advantage of the American system. Roosevelt’s New Deal might have attempted to rectify unemployment with government jobs, but Johnson’s Great Society and its imitators funded government-sponsored job training, even in places without available jobs. Union leaders in the 1950s and 1960s typically supported such programs and philosophies.

Internal racism also weakened the labor movement. While national CIO leaders encouraged Black unionization in the 1930s, white workers on the ground often opposed the integrated shop. In Detroit and elsewhere after World War II, white workers participated in “hate strikes” where they walked off the job rather than work with African Americans. White workers similarly opposed residential integration, fearing, among other things, that Black newcomers would lower property values.38

By the mid-1970s, widely shared postwar prosperity leveled off and began to retreat. Growing international competition, technological inefficiency, and declining productivity gains stunted working- and middle-class wages. As the country entered recession, wages decreased and the pay gap between workers and management expanded, reversing three decades of postwar contraction. At the same time, dramatic increases in mass incarceration coincided with the deregulation of prison labor to allow more private companies access to cheaper inmate labor, a process that, whatever its aggregate impact, impacted local communities where free jobs were moved into prisons. The tax code became less progressive and labor lost its foothold in the marketplace. Unions represented a third of the workforce in the 1950s, but only one in ten workers belonged to one as of 2015.39

Geography dictated much of labor’s fall, as American firms fled pro-labor states in the 1970s and 1980s. Some went overseas in the wake of new trade treaties to exploit low-wage foreign workers, but others turned to anti-union states in the South and West stretching from Virginia to Texas to Southern California. Factories shuttered in the North and Midwest, leading commentators by the 1980s to dub America’s former industrial heartland the Rust Belt. With this, they contrasted the prosperous and dynamic Sun Belt.”

Urban decay confronted Americans of the 1960s and 1970s. As the economy sagged and deindustrialization hit much of the country, Americans increasingly associated major cities with poverty and crime. In this 1973 photo, two subway riders sit amid a graffitied subway car in New York City. National Archives (8464439).

Coined by journalist Kevin Phillips in 1969, the term Sun Belt refers to the swath of southern and western states that saw unprecedented economic, industrial, and demographic growth after World War II.40 During the New Deal, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared the American South “the nation’s No. 1 economic problem” and injected massive federal subsidies, investments, and military spending into the region. During the Cold War, Sun Belt politicians lobbied hard for military installations and government contracts for their states.41

Meanwhile, southern states’ hostility toward organized labor beckoned corporate leaders. The Taft-Hartley Act in 1947 facilitated southern states’ frontal assault on unions. Thereafter, cheap, nonunionized labor, low wages, and lax regulations pulled northern industries away from the Rust Belt. Skilled northern workers followed the new jobs southward and westward, lured by cheap housing and a warm climate slowly made more tolerable by modern air conditioning.

The South attracted business but struggled to share their profits. Middle-class whites grew prosperous, but often these were recent transplants, not native southerners. As the cotton economy shed farmers and laborers, poor white and Black southerners found themselves mostly excluded from the fruits of the Sun Belt. Public investments were scarce. White southern politicians channeled federal funding away from primary and secondary public education and toward high-tech industry and university-level research. The Sun Belt inverted Rust Belt realities: the South and West had growing numbers of high-skill, high-wage jobs but lacked the social and educational infrastructure needed to train native poor and middle-class workers for those jobs.

Regardless, more jobs meant more people, and by 1972, southern and western Sun Belt states had more electoral votes than the Northeast and Midwest. This gap continues to grow.42 Though the region’s economic and political ascendance was a product of massive federal spending, New Right politicians who constructed an identity centered on “small government” found their most loyal support in the Sun Belt. These business-friendly politicians successfully synthesized conservative Protestantism and free market ideology, creating a potent new political force. Housewives organized reading groups in their homes, and from those reading groups sprouted new organized political activities. Prosperous and mobile, old and new suburbanites gravitated toward an individualistic vision of free enterprise espoused by the Republican Party. Some, especially those most vocally anticommunist, joined groups like the Young Americans for Freedom and the John Birch Society. Less radical suburban voters, however, still gravitated toward the more moderate brand of conservatism promoted by Richard Nixon.

VII. The Politics of Love, Sex, and Gender

Demonstrators opposed to the Equal Rights Amendment protest in front of the White House in 1977. Library of Congress.

The sexual revolution continued into the 1970s. Many Americans—feminists, gay men, lesbians, and straight couples—challenged strict gender roles and rejected the rigidity of the nuclear family. Cohabitation without marriage spiked, straight couples married later (if at all), and divorce levels climbed. Sexuality, decoupled from marriage and procreation, became for many not only a source of personal fulfillment but a worthy political cause.

At the turn of the decade, sexuality was considered a private matter yet rigidly regulated by federal, state, and local law. Statutes typically defined legitimate sexual expression within the confines of patriarchal, procreative marriage. Interracial marriage, for instance, was illegal in many states until 1967 and remained largely taboo long after. Same-sex intercourse and cross-dressing were criminalized in most states, and gay men, lesbians, and transgender people were vulnerable to violent police enforcement as well as discrimination in housing and employment.

Two landmark legal rulings in 1973 established the battle lines for the “sex wars” of the 1970s. First, the Supreme Court’s 7–2 ruling in Roe v. Wade (1973) struck down a Texas law that prohibited abortion in all cases when a mother’s life was not in danger. The Court’s decision built on precedent from a 1965 ruling that, in striking down a Connecticut law prohibiting married couples from using birth control, recognized a constitutional “right to privacy.”43 In Roe, the Court reasoned that “this right of privacy . . . is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.”44 The Court held that states could not interfere with a woman’s right to an abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy and could only fully prohibit abortions during the third trimester.

Other Supreme Court rulings, however, found that sexual privacy could be sacrificed for the sake of “public” good. Miller v. California (1973), a case over the unsolicited mailing of sexually explicit advertisements for illustrated “adult” books, held that the First Amendment did not protect “obscene” material, defined by the Court as anything with sexual appeal that lacked, “serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”45 The ruling expanded states’ abilities to pass laws prohibiting materials like hard-core pornography. However, uneven enforcement allowed pornographic theaters and sex shops to proliferate despite whatever laws states had on the books. Americans debated whether these represented the pinnacle of sexual liberation or, as poet and lesbian feminist Rita Mae Brown suggested, “the ultimate conclusion of sexist logic.”46

Of more tangible concern for most women, though, was the right to equal employment access. Thanks partly to the work of Black feminists like Pauli Murray, Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act banned employment discrimination based on sex, in addition to race, color, religion, and national origin. “If sex is not included,” she argued in a memorandum sent to members of Congress, “the civil rights bill would be including only half of the Negroes.”47 Like most laws, Title VII’s full impact came about slowly, as women across the nation cited it to litigate and pressure employers to offer them equal opportunities compared to those they offered to men. For one, employers in the late sixties and seventies still viewed certain occupations as inherently feminine or masculine. NOW organized airline workers against a major company’s sexist ad campaign that showed female flight attendants wearing buttons that read, “I’m Debbie, Fly Me” or “I’m Cheryl, Fly Me.” Actual female flight attendants were required to wear similar buttons.48 Other women sued to gain access to traditionally male jobs like factory work. Protests prompted the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to issue a more robust set of protections between 1968 and 1971. Though advancement came haltingly and partially, women used these protections to move eventually into traditional male occupations, politics, and corporate management.

The battle for sexual freedom was not just about the right to get into places, though. It was also about the right to get out of them—specifically, unhappy households and marriages. Between 1959 and 1979, the American divorce rate more than doubled. By the early 1980s, nearly half of all American marriages ended in divorce.49 The stigma attached to divorce evaporated and a growing sense of sexual and personal freedom motivated individuals to leave abusive or unfulfilling marriages. Legal changes also promoted higher divorce rates. Before 1969, most states required one spouse to prove that the other was guilty of a specific offense, such as adultery. The difficulty of getting a divorce under this system encouraged widespread lying in divorce courts. Even couples desiring an amicable split were sometimes forced to claim that one spouse had cheated on the other even if neither (or both) had. Other couples temporarily relocated to states with more lenient divorce laws, such as Nevada.50 Widespread recognition of such practices prompted reforms. In 1969, California adopted the first no-fault divorce law. By the end of the 1970s, almost every state had adopted some form of no-fault divorce. The new laws allowed for divorce on the basis of “irreconcilable differences,” even if only one party felt that he or she could not stay in the marriage.51

Gay men and women, meanwhile, negotiated a harsh world that stigmatized homosexuality as a mental illness or an immoral depravity. Building on postwar efforts by gay rights organizations to bring homosexuality into the mainstream of American culture, young gay activists of the late sixties and seventies began to challenge what they saw as the conservative gradualism of the “homophile” movement. Inspired by the burgeoning radicalism of the Black Power movement, the New Left protests of the Vietnam War, and the counterculture movement for sexual freedom, gay and lesbian activists agitated for a broader set of sexual rights that emphasized an assertive notion of liberation rooted not in mainstream assimilation but in pride of sexual difference.

Perhaps no single incident did more to galvanize gay and lesbian activism than the 1969 uprising at the Stonewall Inn in New York City’s Greenwich Village. Police regularly raided gay bars and hangouts. But when police raided the Stonewall in June 1969, the bar patrons protested and sparked a multiday street battle that catalyzed a national movement for gay liberation. Seemingly overnight, calls for homophile respectability were replaced with chants of “Gay Power!”52

The window under the Stonewall Inn sign reads: “We homosexuals plead with our people to please help maintain peaceful and quiet conduct on the streets of the Village–Mattachine.” Photograph 1969. Wikimedia.

In the following years, gay Americans gained unparalleled access to private and public spaces. Gay activists increasingly attacked cultural norms that demanded they keep their sexuality hidden. Citing statistics that sexual secrecy contributed to stigma and suicide, gay activists urged people to come out and embrace their sexuality. A step towards the normalization of homosexuality occurred in 1973, when the American Psychiatric Association stopped classifying homosexuality as a mental illness. Pressure mounted on politicians. In 1982, Wisconsin became the first state to ban discrimination based on sexual orientation. More than eighty cities and nine states followed suit over the following decade. But progress proceeded unevenly, and gay Americans continued to suffer hardships from a hostile culture.

Like all social movements, the sexual revolution was not free of division. Transgender people were often banned from participating in Gay Pride rallies and lesbian feminist conferences. They, in turn, mobilized to fight the high incidence of rape, abuse, and murder of transgender people. A 1971 newsletter denounced the notion that transgender people were mentally ill and highlighted the particular injustices they faced in and out of the gay community, declaring, “All power to Trans Liberation.”53

As events in the 1970s broadened sexual freedoms and promoted greater gender equality, so too did they generate sustained and organized opposition. Evangelical Christians and other moral conservatives, for instance, mobilized to reverse gay victories. In 1977, activists in Dade County, Florida, used the slogan “Save Our Children” to overturn an ordinance banning discrimination based on sexual orientation.54 A leader of the ascendant religious right, Jerry Falwell, said in 1980, “It is now time to take a stand on certain moral issues. . . . We must stand against the Equal Rights Amendment, the feminist revolution, and the homosexual revolution. We must have a revival in this country.”55

Much to Falwell’s delight, conservative Americans did, in fact, stand against and defeat the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), their most stunning social victory of the 1970s. Versions of the amendment—which declared, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of sex”—were introduced to Congress each year since 1923. It finally passed amid the upheavals of the sixties and seventies and went to the states for ratification in March 1972.56 With high approval ratings, the ERA seemed destined to pass swiftly through state legislatures and become the Twenty-Seventh Amendment. Hawaii ratified the amendment the same day it cleared Congress. Within a year, thirty states had done so. But then the amendment stalled. It took years for more states to pass it. In 1977, Indiana became the thirty-fifth and final state to ratify.57

By 1977, anti-ERA forces had successfully turned the political tide against the amendment. At a time when many women shared Betty Friedan’s frustration that society seemed to confine women to the role of homemaker, Phyllis Schlafly’s STOP ERA organization (“Stop Taking Our Privileges”) trumpeted the value and advantages of being a homemaker and mother.58 Marshaling the support of evangelical Christians and other religious conservatives, Schlafly worked tirelessly to stifle the ERA. She lobbied legislators and organized counter-rallies to ensure that Americans heard “from the millions of happily married women who believe in the laws which protect the family and require the husband to support his wife and children.”59 The amendment needed only three more states for ratification. It never got them. In 1982, the time limit for ratification expired—and along with it, the amendment.60

The failed battle for the ERA uncovered the limits of the feminist crusade. And it illustrated the women’s movement’s inherent incapacity to represent fully the views of 50 percent of the country’s population, a population riven by class differences, racial disparities, and cultural and religious divisions.

VIII. The Misery Index

Supporters rally with pumpkins carved in the likeness of President Jimmy Carter in Polk County, Florida, in October 1980. State Library and Archives of Florida via Flickr.

Although Nixon eluded prosecution, Watergate continued to weigh on voters’ minds. It netted big congressional gains for Democrats in the 1974 midterm elections, and Ford’s pardon damaged his chances in 1976. Former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter, a nuclear physicist and peanut farmer who represented the rising generation of younger, racially liberal “New South” Democrats, captured the Democratic nomination. Carter did not identify with either his party’s liberal or conservative wing; his appeal was more personal and moral than political. He ran on no great political issues, letting his background as a hardworking, honest, southern Baptist navy man ingratiate him to voters around the country, especially in his native South, where support for Democrats had wavered in the wake of the civil rights movement. Carter’s wholesome image was painted in direct contrast to the memory of Nixon, and by association with the man who pardoned him. Carter sealed his party’s nomination in June and won a close victory in November.61

When Carter took the oath of office on January 20, 1977, however, he became president of a nation in the midst of economic turmoil. Oil shocks, inflation, stagnant growth, unemployment, and sinking wages weighed down the nation’s economy. Some of these problems were traceable to the end of World War II when American leaders erected a complex system of trade policies to help rebuild the shattered economies of Western Europe and Asia. After the war, American diplomats and politicians used trade relationships to win influence and allies around the globe. They saw the economic health of their allies, particularly West Germany and Japan, as a crucial bulwark against the expansion of communism. Americans encouraged these nations to develop vibrant export-oriented economies and tolerated restrictions on U.S. imports.

The 1979 energy crisis panicked consumers who remembered the 1973 oil shortage, prompting many Americans to buy oil in huge quantities. Library of Congress.

This came at great cost to the United States. As the American economy stalled, Japan and West Germany soared and became major forces in the global production for autos, steel, machine tools, and electrical products. By 1970, the United States began to run massive trade deficits. The value of American exports dropped and the prices of its imports skyrocketed. Coupled with the huge cost of the Vietnam War and the rise of oil-producing states in the Middle East, growing trade deficits sapped the United States’ dominant position in the global economy.

American leaders didn’t know how to respond. After a series of negotiations with leaders from France, Great Britain, West Germany, and Japan in 1970 and 1971, the Nixon administration allowed these rising industrial nations to continue flouting the principles of free trade. They maintained trade barriers that sheltered their domestic markets from foreign competition while at the same time exporting growing amounts of goods to the United States. By 1974, in response to U.S. complaints and their own domestic economic problems, many of these industrial nations overhauled their protectionist practices but developed even subtler methods (such as state subsidies for key industries) to nurture their economies.

The result was that Carter, like Ford before him, presided over a hitherto unimagined economic dilemma: the simultaneous onset of inflation and economic stagnation, a combination popularized as stagflation.”62 Neither Ford nor Carter had the means or ambition to protect American jobs and goods from foreign competition. As firms and financial institutions invested, sold goods, and manufactured in new rising economies like Mexico, Taiwan, Japan, Brazil, and elsewhere, American politicians allowed them to sell their often cheaper products in the United States.

As American officials institutionalized this new unfettered global trade, many American manufacturers perceived only one viable path to sustained profitability: moving overseas, often by establishing foreign subsidiaries or partnering with foreign firms. Investment capital, especially in manufacturing, fled the United States looking for overseas investments and hastened the decline in the productivity of American industry.

During the 1976 presidential campaign, Carter had touted the “misery index,” the simple addition of the unemployment rate to the inflation rate, as an indictment of Gerald Ford and Republican rule. But Carter failed to slow the unraveling of the American economy, and the stubborn and confounding rise of both unemployment and inflation damaged his presidency.

Just as Carter failed to offer or enact policies to stem the unraveling of the American economy, his idealistic vision of human rights–based foreign policy crumbled. He had not made human rights a central theme in his campaign, but in May 1977 he declared his wish to move away from a foreign policy in which “inordinate fear of communism” caused American leaders to “adopt the flawed and erroneous principles and tactics of our adversaries.” Carter proposed instead “a policy based on constant decency in its values and on optimism in our historical vision.”63

Carter’s human rights policy achieved real victories: the United States either reduced or eliminated aid to American-supported right-wing dictators guilty of extreme human rights abuses in places like South Korea, Argentina, and the Philippines. In September 1977, Carter negotiated the return to Panama of the Panama Canal, which cost him enormous political capital in the United States.64 A year later, in September 1978, Carter negotiated a peace treaty between Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian president Anwar Sadat. The Camp David Accords—named for the president’s rural Maryland retreat, where thirteen days of secret negotiations were held—represented the first time an Arab state had recognized Israel, and the first time Israel promised Palestine self-government. The accords had limits, for both Israel and the Palestinians, but they represented a major foreign policy coup for Carter.65

And yet Carter’s dreams of a human rights–based foreign policy crumbled before the Cold War and the realities of American politics. The United States continued to provide military and financial support for dictatorial regimes vital to American interests, such as the oil-rich state of Iran. When the President and First Lady Rosalynn Carter visited Tehran, Iran, in January 1978, the president praised the nation’s dictatorial ruler, Shah Reza Pahlavi, and remarked on the “respect and the admiration and love” Iranians had for their leader.66 When the shah was deposed in November 1979, revolutionaries stormed the American embassy in Tehran and took fifty-two Americans hostage. Americans not only experienced another oil crisis as Iran’s oil fields shut down, they watched America’s news programs, for 444 days, remind them of the hostages and America’s new global impotence. Carter couldn’t win their release. A failed rescue mission only ended in the deaths of eight American servicemen. Already beset with a punishing economy, Carter’s popularity plummeted.

Carter’s efforts to ease the Cold War by achieving a new nuclear arms control agreement disintegrated under domestic opposition from conservative Cold War hawks such as Ronald Reagan, who accused Carter of weakness. A month after the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in December 1979, a beleaguered Carter committed the United States to defending its “interests” in the Middle East against Soviet incursions, declaring that “an assault [would] be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.” The Carter Doctrine not only signaled Carter’s ambivalent commitment to de-escalation and human rights, it testified to his increasingly desperate presidency.67

The collapse of American manufacturing, the stubborn rise of inflation, the sudden impotence of American foreign policy, and a culture ever more divided: the sense of unraveling pervaded the nation. “I want to talk to you right now about a fundamental threat to American democracy,” Jimmy Carter said in a televised address on July 15, 1979. “The threat is nearly invisible in ordinary ways. It is a crisis of confidence. It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will.”

IX. Conclusion

Though American politics moved right after Lyndon Johnson’s administration, Nixon’s 1968 election was no conservative counterrevolution. American politics and society remained in flux throughout the 1970s. American politicians on the right and the left pursued relatively moderate courses compared to those in the preceding and succeeding decades. But a groundswell of anxieties and angers brewed beneath the surface. The world’s greatest military power had floundered in Vietnam and an American president stood flustered by Middle Eastern revolutionaries. The cultural clashes from the sixties persisted and accelerated. While cities burned, a more liberal sexuality permeated American culture. The economy crashed, leaving America’s cities prone before poverty and crime and its working class gutted by deindustrialization and globalization. American weakness was everywhere. And so, by 1980, many Americans—especially white middle- and upper-class Americans—felt a nostalgic desire for simpler times and simpler answers to the frustratingly complex geopolitical, social, and economic problems crippling the nation. The appeal of Carter’s soft drawl and Christian humility had signaled this yearning, but his utter failure to stop the unraveling of American power and confidence opened the way for a new movement, one with new personalities and a new conservatism—one that promised to undo the damage and restore the United States to its own nostalgic image of itself.

Notes

- Acts included Santana; Jefferson Airplane; Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young; and the Flying Burrito Brothers. The Grateful Dead were scheduled but refused to play.

- Bruce J. Schulman, The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Society, and Politics (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2002), 18

- Allen J. Matusow, The Unraveling of America: A History of Liberalism in the 1960s, updated ed. (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2009), 304–305.

- Owen Gleibman, “Altamont at 45: The Most Dangerous Rock Concert,” BBC, December 5, 2014, http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20141205-did-altamont-end-the-60s.

- Jeff Leen, “The Vietnam Protests: When Worlds Collided,” Washington Post, September 27, 1999, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/local/2000/vietnam092799.htm.

- Michael J. Arlen, Living-Room War (New York: Viking, 1969).

- Tom Engelhardt, The End of Victory Culture: Cold War America and the Disillusioning of a Generation, rev. ed. (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007), 190.

- Mitchel P. Roth, Historical Dictionary of War Journalism (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1997), 105.

- David L. Anderson, The Columbia Guide to the Vietnam War (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 109.

- Guenter Lewy, America in Vietnam (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), 325–326.

- Lyndon B. Johnson, “Address to the Nation Announcing Steps to Limit the War in Vietnam and Reporting His Decision Not to Seek Reelection,” March 31, 1968, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library, http://www.lbjlib.utexas.edu/johnson/archives.hom/speeches.hom/680331.asp.

- Lewy, America in Vietnam, 164–169; Henry Kissinger, Ending the Vietnam War: A History of America’s Involvement in and Extrication from the Vietnam War (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2003), 81–82.

- Richard Nixon, “Address to the Nation Announcing Conclusion of an Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam,” January 23, 1973, American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=3808.

- Richard Nixon, quoted in Walter Isaacson, Kissinger: A Biography (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005), 163–164.

- Geneva Jussi Hanhimaki, The Flawed Architect: Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 257.

- Cohen, Consumer’s Republic).

- Quotes from “Lionel Moves into the Neighborhood,” All in the Family, season 1, episode 8 (1971), http://www.tvrage.com/all-in-the-family/episodes/5587.

- Jim Dawson and Steve Propes, 45 RPM: The History, Heroes and Villains of a Pop Music Revolution (San Francisco: Backbeat Books, 2003), 120.

- Roger Ebert, “Review of Dirty Harry,” January 1, 1971, http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/dirty-harry-1971.

- Ronald P. Formisano, Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991).

- Michael W. Flamm, Law and Order: Street Crime, Civil Unrest, and the Crisis of Liberalism in the 1960s (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 58–59, 85–93.

- Thomas J. Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North (New York: Random House, 2008), 348.

- Cohen, Consumer’s Republic, 373.

- Ibid., 376.

- Martin Luther King, quoted in David J. Garrow, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (New York: Morrow, 1986), 439.

- Richard M. Nixon, “Address to the Nation on the War in Vietnam,” November 3, 1969, American Experience, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/primary-resources/nixon-vietnam/.

- Richard Nixon, “Address to the Nation about Policies to Deal with Energy Shortages,” November 7, 1973, American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=4034.

- Office of the Historian, “Oil Embargo, 1973–1974,” U.S. Department of State, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/oil-embargo.

- “Gas Explodes in Man’s Car,” Uniontown (PA) Morning Herald, December 5, 1973, p. 12.

- Larry H. Addington, America’s War in Vietnam: A Short Narrative History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000), 140–141.

- Schulman, Seventies, 44.

- “Executive Privilege,” in John J. Patrick, Richard M. Pious, and Donald A. Ritchie, The Oxford Guide to the United States Government (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 227; Schulman, The Seventies, 44–48.

- Sugrue, Origins of the Urban Crisis, 132.

- Ibid., 136, 149.

- Ibid., 144.

- Ibid., 144.

- Ibid., 261.

- Jefferson Cowie and Nick Salvatore, “The Long Exception: Rethinking the Place of the New Deal in American History,” International Labor and Working-Class History 74 (Fall 2008), 1–32, esp. 9.

- Quoctrung Bui, “50 Years of Shrinking Union Membership in One Map,” February 23, 2015, NPR, http://www.npr.org/sections/money/2015/02/23/385843576/50–years-of-shrinking-union-membership-in-one-map.

- Kevin P. Phillips, The Emerging Republic Majority (New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1969), 17.

- Bruce J. Schulman, From Cotton Belt to Sunbelt: Federal Policy, Economic Development, and the Transformation of the South, 1938–1980, 3rd printing (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 3.

- William H. Frey, “The Electoral College Moves to the Sun Belt,” research brief, Brookings Institution, May 2005.

- Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479, June 7, 1965.

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, January 22, 1973.

- Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15, June 21, 1973.

- Rita Mae Brown, quoted in David Allyn, Make Love, Not War—The Sexual Revolution: An Unfettered History (New York: Routledge, 2001), 239.

- Nancy MacLean, Freedom Is Not Enough: The Opening of the American Workplace (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 121.

- Ibid., 129.

- Arland Thornton, William G. Axinn, and Yu Xie, Marriage and Cohabitation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 57.

- Glenda Riley, Divorce: An American Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 135–139.

- Ibid., 161–165; Mary Ann Glendon, The Transformation of Family Law: State, Law, and Family in the United States and Western Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 188–189.

- David Carter, Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004), 147.

- Trans Liberation Newsletter, in Susan Styker, Transgender History (Berkeley, CA: Seal Press, 2008), 96–97.

- William N. Eskridge, Dishonorable Passions: Sodomy Laws in America, 1861–2003 (New York: Viking, 2008), 209–212.

- Jerry Falwell, Listen, America! (Garden City, NY: Doubleday), 19.

- Donald Critchlow, Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism: A Woman’s Crusade (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 213–216.

- Ibid., 218–219; Joel Krieger, ed., The Oxford Companion to the Politics of the World, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 256.

- Critchlow, Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism, 219.

- Phyllis Schlafly, quoted in Christine Stansell, The Feminist Promise: 1792 to the Present (New York: Modern Library, 2010), 340.

- Critchlow, Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism, 281.

- Sean Wilentz, The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974–2008 (New York: HarperCollins, 2008), 69–72.

- Ibid., 75.

- Jimmy Carter, “University of Notre Dame—Address at the Commencement Exercises at the University,” May 22, 1977, American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=7552.

- Wilentz, Age of Reagan, 100–102.

- Harvey Sicherman, Palestinian Autonomy, Self-Government, and Peace (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1993), 35.

- Jimmy Carter, “Tehran, Iran Toasts of the President and the Shah at a State Dinner,” December 31, 1977, American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=7080.

- Jimmy Carter, “The State of the Union Address,” January 23, 1980, American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=33079.