Supporters of defeated U.S. President Donald Trump cheer the breaching of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. Via Wikimedia.

The U.S. Capitol was stormed on January 6, 2021. Thousands of right-wing protestors, fueled by an onslaught of lies and fabrications and conspiracy theories surrounding the November 2020 elections, rallied that morning in front of the White House to “Stop the Steal.” Repeating a familiar litany of lies and distortions, the sitting president of the United States then urged them to march on the Capitol and stop the certification of the November electoral vote. “You’ll never take back our country with weakness,” he said. “Fight like hell,” he said. “If you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.”1 And so they did. They marched on the capitol, armed themselves with metal pipes, baseball bats, hockey sticks, pepper spray, stun guns, and flag poles, and attacked the police officers barricading the building.

“It was like something from a medieval battle,” Capitol Police Officer Aquilino Gonell recalled 2 The mob pulled D.C. Metropolitan Police Officer Michael Fanone into the crowd, beat him with flagpoles, and tasered him. “Kill him with his own gun,” Fanone remembered the mob shouting just before he lost consciousness. “I can still hear those words in my head today,” he testified six months later.3

The mob breached the barriers and poured into the building, marking perhaps the greatest domestic assault on the American federal government since the Civil War. But the events of January 6 were rooted in history.

Revolutionary technological change, unprecedented global flows of goods and people and capital, an amorphous decades-long War on Terror, accelerating inequality, growing diversity, a changing climate, political stalemate: our present is not an island of circumstance but a product of history. Time marches forever on. The present becomes the past, but, as William Faulkner famously put it, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”4 The last several decades of American history have culminated in the present, an era of innovation and advancement but also of stark partisan division, racial and ethnic tension, protests, gender divides, uneven economic growth, widening inequalities, military interventions, bouts of mass violence, and pervasive anxieties about the present and future of the United States. Through boom and bust, national tragedy, foreign wars, and the maturation of a new generation, a new chapter of American history is busy being written.

The War on Terror was a centerpiece in the race for the White House in 2004. The Democratic ticket, headed by Massachusetts senator John F. Kerry, a Vietnam War hero who entered the public consciousness for his subsequent testimony against it, attacked Bush for the ongoing inability to contain the Iraqi insurgency or to find weapons of mass destruction, the revelation and photographic evidence that American soldiers had abused prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison outside Baghdad, and the inability to find Osama bin Laden. Moreover, many enemy combatants who had been captured in Iraq and Afghanistan were “detained” indefinitely at a military prison in Guantanamo Bay in Cuba. “Gitmo” became infamous for its harsh treatment, indefinite detentions, and torture of prisoners. Bush defended the War on Terror, and his allies attacked critics for failing to “support the troops.” Moreover, Kerry had voted for the war—he had to attack the very thing that he had authorized. Bush won a close but clear victory.

The second Bush term saw the continued deterioration of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but Bush’s presidency would take a bigger hit from his perceived failure to respond to the domestic tragedy that followed Hurricane Katrina’s devastating hit on the Gulf Coast. Katrina had been a category 5 hurricane. It was, the New Orleans Times-Picayune reported, “the storm we always feared.”5

New Orleans suffered a direct hit, the levees broke, and the bulk of the city flooded. Thousands of refugees flocked to the Superdome, where supplies and medical treatment and evacuation were slow to come. Individuals died in the heat. Bodies wasted away. Americans saw poor Black Americans abandoned. Katrina became a symbol of a broken administrative system, a devastated coastline, and irreparable social structures that allowed escape and recovery for some and not for others. Critics charged that Bush had staffed his administration with incompetent supporters and had further ignored the displaced poor and Black residents of New Orleans.6

Hurricane Katrina was one of the deadliest and more destructive hurricanes to hit American soil in U.S. history. It nearly destroyed New Orleans, Louisiana, as well as cities, towns, and rural areas across the Gulf Coast. It sent hundreds of thousands of refugees to near-by cities like Houston, Texas, where they temporarily resided in massive structures like the Astrodome. Photograph, September 1, 2005. Wikimedia.

Immigration, meanwhile, had become an increasingly potent political issue. The Clinton administration had overseen the implementation of several anti-immigration policies on the U.S.-Mexico border, but hunger and poverty were stronger incentives than border enforcement policies were deterrents. Illegal immigration continued, often at great human cost, but nevertheless fanned widespread anti-immigration sentiment among many American conservatives. But George W. Bush used the issue to win re-election and Republicans used it in the 2006 mid-terms, passing legislation—with bipartisan support—that provided for a border “fence.” 700 miles of towering steel barriers sliced through border towns and deserts. Many immigrants and their supporters tried to fight back. The spring and summer of 2006 saw waves of protests across the country. Hundreds of thousands marched in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, and tens of thousands marched in smaller cities around the country. Legal change, however, went nowhere. Moderate conservatives feared upsetting business interests’ demand for cheap, exploitable labor and alienating large voting blocs by stifling immigration, and moderate liberals feared upsetting anti-immigrant groups by pushing too hard for liberalization of immigration laws. The fence was built and the border was tightened.

At the same time, Iraq descended further into chaos as insurgents battled against American troops and groups such as Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s al-Qaeda in Iraq bombed civilians and released video recordings of beheadings. In 2007, twenty-seven thousand additional U.S. forces deployed to Iraq under the command of General David Petraeus. The effort, “the surge,” employed more sophisticated anti-insurgency strategies and, combined with Sunni efforts, pacified many of Iraq’s cities and provided cover for the withdrawal of American forces. On December 4, 2008, the Iraqi government approved the U.S.-Iraq Status of Forces Agreement, and U.S. combat forces withdrew from Iraqi cities before June 30, 2009. The last U.S. combat forces left Iraq on December 18, 2011. Violence and instability continued to rock the country.

Afghanistan, meanwhile, had also continued to deteriorate. In 2006, the Taliban reemerged, as the Afghan government proved both highly corrupt and incapable of providing social services or security for its citizens. The Taliban began re-acquiring territory. Money and American troops continued to prop up the Afghanistan government until American forces withdrew hastily in August 2021. The Taliban immediately took over the remainder of the country, outlasting America’s twenty-year occupation.

The Great Recession began, as most American economic catastrophes began, with the bursting of a speculative bubble. Throughout the 1990s and into the new millennium, home prices continued to climb, and financial services firms looked to cash in on what seemed to be a safe but lucrative investment. After the dot-com bubble burst, investors searched for a secure investment rooted in clear value, rather than in trendy technological speculation. What could be more secure than real estate? But mortgage companies began writing increasingly risky loans and then bundling them together and selling them over and over again, sometimes so quickly that it became difficult to determine exactly who owned what.

Decades of financial deregulation had rolled back Depression-era restraints and again allowed risky business practices to dominate the world of American finance. It was a bipartisan agenda. In the 1990s, for instance, Bill Clinton signed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, repealing provisions of the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act separating commercial and investment banks, and the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, which exempted credit-default swaps—perhaps the key financial mechanism behind the crash—from regulation.

Mortgages had been so heavily leveraged that when American homeowners began to default on their loans, the whole system collapsed. Major financial services firms such as Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers disappeared almost overnight. In order to prevent the crisis from spreading, President Bush signed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act and the federal government immediately began pouring billions of dollars into the industry, propping up hobbled banks. Massive giveaways to bankers created shock waves of resentment throughout the rest of the country, contributing to Obama’s 2008 election. But Obama oversaw the program after his inauguration. Thereafter, conservative members of the Tea Party decried the cronyism of an incoming Obama administration filled with former Wall Street executives. The same energies also motivated the Occupy Wall Street movement, as mostly young left-leaning New Yorkers protested an American economy that seemed overwhelmingly tilted toward “the one percent.”7

The Great Recession only magnified already rising income and wealth inequalities. According to the chief investment officer at JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the United States, “profit margins have reached levels not seen in decades,” and “reductions in wages and benefits explain the majority of the net improvement.”8 A study from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) found that since the late 1970s, after-tax benefits of the wealthiest 1 percent grew by over 300 percent. The “average” American’s after-tax benefits had grown 35 percent. Economic trends have disproportionately and objectively benefited the wealthiest Americans. Still, despite political rhetoric, American frustration failed to generate anything like the social unrest of the early twentieth century. A weakened labor movement and a strong conservative bloc continue to stymie serious attempts at reversing or even slowing economic inequalities. Occupy Wall Street managed to generate a fair number of headlines and shift public discussion away from budget cuts and toward inequality, but its membership amounted to only a fraction of the far more influential and money-driven Tea Party. Its presence on the public stage was fleeting.

The Great Recession, however, was not. While American banks quickly recovered and recaptured their steady profits, and the American stock market climbed again to new heights, American workers continued to lag. Job growth was slow and unemployment rates would remain stubbornly high for years. Wages froze, meanwhile, and well-paying full-time jobs that were lost were too often replaced by low-paying, part-time work. A generation of workers coming of age within the crisis, moreover, had been savaged by the economic collapse. Unemployment among young Americans hovered for years at rates nearly double the national average.

In 2008, Barack Obama became the first African American elected to the presidency. In this official White House photo from May, 2009, 5-year-old Jacob Philadelphia said, “I want to know if my hair is just like yours.” The White House via Flickr.

By the 2008 election, with Iraq still in chaos, Democrats were ready to embrace the antiwar position and sought a candidate who had consistently opposed military action in Iraq. Senator Barack Obama had only been a member of the Illinois state senate when Congress debated the war actions, but he had publicly denounced the war, predicting the sectarian violence that would ensue, and remained critical of the invasion through his 2004 campaign for the U.S. Senate. He began running for president almost immediately after arriving in Washington.

A former law professor and community activist, Obama became the first African American candidate to ever capture the nomination of a major political party.9 During the election, Obama won the support of an increasingly antiwar electorate. When an already fragile economy finally collapsed in 2007 and 2008, Bush’s policies were widely blamed. Obama’s opponent, Republican senator John McCain, was tied to those policies and struggled to fight off the nation’s desire for a new political direction. Obama won a convincing victory in the fall and became the nation’s first African American president.

President Obama’s first term was marked by domestic affairs, especially his efforts to combat the Great Recession and to pass a national healthcare law. Obama came into office as the economy continued to deteriorate. He continued the bank bailout begun under his predecessor and launched a limited economic stimulus plan to provide government spending to reignite the economy.

Despite Obama’s dominant electoral victory, national politics fractured, and a conservative Republican firewall quickly arose against the Obama administration. The Tea Party became a catch-all term for a diffuse movement of fiercely conservative and politically frustrated American voters. Typically whiter, older, and richer than the average American, flush with support from wealthy backers, and clothed with the iconography of the Founding Fathers, Tea Party activists registered their deep suspicions of the federal government.10 Tea Party protests dominated the public eye in 2009 and activists steered the Republican Party far to the right, capturing primary elections all across the country.

Obama’s most substantive legislative achievement proved to be a national healthcare law, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare). Presidents since Theodore Roosevelt had striven to pass national healthcare reform and failed. Obama’s plan forsook liberal models of a national healthcare system and instead adopted a heretofore conservative model of subsidized private care (similar plans had been put forward by Republicans Richard Nixon, Newt Gingrich, and Obama’s 2012 opponent, Mitt Romney). Beset by conservative protests, Obama’s healthcare reform narrowly passed through Congress. It abolished pre-existing conditions as a cause for denying care, scrapped junk plans, provided for state-run healthcare exchanges (allowing individuals without healthcare to pool their purchasing power), offered states funds to subsidize an expansion of Medicaid, and required all Americans to provide proof of a health insurance plan that measured up to government-established standards (those who did not purchase a plan would pay a penalty tax, and those who could not afford insurance would be eligible for federal subsidies). The number of uninsured Americans remained stubbornly high, however, and conservatives spent most of the next decade attacking the bill.

Meanwhile, in 2009, President Barack Obama deployed seventeen thousand additional troops to Afghanistan as part of a counterinsurgency campaign that aimed to “disrupt, dismantle, and defeat” al-Qaeda and the Taliban. Meanwhile, U.S. Special Forces and CIA drones targeted al-Qaeda and Taliban leaders. In May 2011, U.S. Navy Sea, Air and Land Forces (SEALs) conducted a raid deep into Pakistan that led to the killing of Osama bin Laden. The United States and NATO began a phased withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2011, with an aim of removing all combat troops by 2014. Although weak militarily, the Taliban remained politically influential in south and eastern Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda remained active in Pakistan but shifted its bases to Yemen and the Horn of Africa. As of December 2013, the war in Afghanistan had claimed the lives of 3,397 U.S. service members.

Former Taliban fighters surrender their arms to the government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan during a reintegration ceremony at the provincial governor’s compound in May 2012. Wikimedia.

In 2012, Barack Obama won a second term by defeating Republican Mitt Romney, the former governor of Massachusetts. However, Obama’s inability to control Congress and the ascendancy of Tea Party Republicans stunted the passage of meaningful legislation. Obama was a lame duck before he ever won reelection, and gridlocked government came to represent an acute sense that much of American life—whether in politics, economics, or race relations—had grown stagnant.

The economy continued its halfhearted recovery from the Great Recession. The Obama administration campaigned on little to specifically address the crisis and, faced with congressional intransigence, accomplished even less. While corporate profits climbed and stock markets soared, wages stagnated and employment sagged for years after the Great Recession. By 2016, the statistically average American worker had not received a raise in almost forty years. The average worker in January 1973 earned $4.03 an hour. Adjusted for inflation, that wage was about two dollars per hour more than the average American earned in 2014. Working Americans were losing ground. Moreover, most income gains in the economy had been largely captured by a small number of wealthy earners. Between 2009 and 2013, 85 percent of all new income in the United States went to the top 1 percent of the population.11

But if money no longer flowed to American workers, it saturated American politics. In 2000, George W. Bush raised a record $172 million for his campaign. In 2008, Barack Obama became the first presidential candidate to decline public funds (removing any applicable caps to his total fund-raising) and raised nearly three quarters of a billion dollars for his campaign. The average House seat, meanwhile, cost about $1.6 million, and the average Senate Seat over $10 million.12 The Supreme Court, meanwhile, removed barriers to outside political spending. In 2002, Senators John McCain and Russ Feingold had crossed party lines to pass the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, bolstering campaign finance laws passed in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal in the 1970s. But political organizations—particularly PACs—exploited loopholes to raise large sums of money and, in 2010, the Supreme Court ruled in Citizens United v. FEC that no limits could be placed on political spending by corporations, unions, and nonprofits. Money flowed even deeper into politics.

The influence of money in politics only heightened partisan gridlock, further blocking bipartisan progress on particular political issues. Climate change, for instance, has failed to transcend partisan barriers. In the 1970s and 1980s, experts substantiated the theory of anthropogenic (human-caused) global warming. Eventually, the most influential of these panels, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded in 1995 that there was a “discernible human influence on global climate.”13 This conclusion, though stated conservatively, was by that point essentially a scientific consensus. By 2007, the IPCC considered the evidence “unequivocal” and warned that “unmitigated climate change would, in the long term, be likely to exceed the capacity of natural, managed and human systems to adapt.”14

Climate change became a permanent and major topic of public discussion and policy in the twenty-first century. Fueled by popular coverage, most notably, perhaps, the documentary An Inconvenient Truth, based on Al Gore’s book and presentations of the same name, addressing climate change became a plank of the American left and a point of denial for the American right. American public opinion and political action still lagged far behind the scientific consensus on the dangers of global warming. Conservative politicians, conservative think tanks, and energy companies waged war to sow questions in the minds of Americans, who remain divided on the question, and so many others.

Much of the resistance to addressing climate change is economic. As Americans looked over their shoulder at China, many refused to sacrifice immediate economic growth for long-term environmental security. Twenty-first-century relations with China remained characterized by contradictions and interdependence. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, China reinvigorated its efforts to modernize its country. By liberating and subsidizing much of its economy and drawing enormous foreign investments, China has posted massive growth rates during the last several decades. Enormous cities rise by the day. In 2000, China had a GDP around an eighth the size of U.S. GDP. Based on growth rates and trends, analysts suggest that China’s economy will bypass that of the United States soon. American concerns about China’s political system have persisted, but money sometimes matters more to Americans. China has become one of the country’s leading trade partners. Cultural exchange has increased, and more and more Americans visit China each year, with many settling down to work and study.

By 2016, American voters were fed up. In that year’s presidential race, Republicans spurned their political establishment and nominated a real estate developer and celebrity billionaire, Donald Trump, who, decrying the tyranny of political correctness and promising to Make America Great Again, promised to build a wall to keep out Mexican immigrants and bar Muslim immigrants. The Democrats, meanwhile, flirted with the candidacy of Senator Bernie Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist from Vermont, before ultimately nominating Hillary Clinton, who, after eight years as first lady in the 1990s, had served eight years in the Senate and four more as secretary of state. Voters despaired: Trump and Clinton were the most unpopular nominees in modern American history. Majorities of Americans viewed each candidate unfavorably and majorities in both parties said, early in the election season, that they were motivated more by voting against their rival candidate than for their own.15 With incomes frozen, politics gridlocked, race relations tense, and headlines full of violence, such frustrations only channeled a larger sense of stagnation, which upset traditional political allegiances. In the end, despite winning nearly three million more votes nationwide, Clinton failed to carry key Midwestern states where frustrated white, working-class voters abandoned the Democratic Party—a Republican president hadn’t carried Wisconsin, Michigan, or Pennsylvania, for instance, since the 1980s—and swung their support to the Republicans. Donald Trump won the presidency.

Donald Trump speaking at a 2018 rally. Photo by Gage Skidmore. Via Wikimedia.

Political divisions only deepened after the election. A nation already deeply split by income, culture, race, geography, and ideology continued to come apart. Trump’s presidency consumed national attention. Traditional print media and the consumers and producers of social media could not help but throw themselves at the ins and outs of Trump’s norm-smashing first years while seemingly refracting every major event through the prism of the Trump presidency. Robert Mueller’s investigation of Russian election-meddling and the alleged collusion of campaign officials in that effort produced countless headlines.

New policies, meanwhile, enflamed widening cultural divisions. Border apprehensions and deportations reached record levels under the Obama administration, and Trump pushed even farther. He pushed for a massive wall along the border to supplement the fence built under the Bush administration. He began ordering the deportation of so-called Dreamers—students who were born elsewhere but grew up in the United States—and immigration officials separated refugee-status-seeking parents and children at the border. Trump’s border policies heartened his base and aggravated his opponents. While Trump enflamed America’s enduring culture war, his narrowly passed 2017 tax cut continued the redistribution of American wealth toward corporations and wealthy individuals. The tax cut grew the federal deficit and further exacerbated America’s widening economic inequality.

In his inaugural address, Donald Trump promised to end what he called “American carnage”—a nation ravaged, he said, by illegal immigrants, crime, and foreign economic competition. But, under his presidency, the nation only spiraled deeper into cultural and racial divisions, domestic unrest, and growing anxiety about the nation’s future. Trump represented an aggressive, pugilistic anti-liberalism, and, as president, never missing an opportunity to fuel on the fires of right-wing rage. Refusing to settle for the careful statement or defer to bureaucrats, Trump smashed many of the norms of the presidency and raged on his personal Twitter account. And he refused to be governed by the truth.

Few Americans, especially after the Johnson and Nixon administrations, believed that presidents never lied. But perhaps no president ever lied so boldly or so often as Donald Trump, who made, according to one accounting, an untrue statement every day for the first forty days of his presidency.16 By the latter years of his presidency, only about a third of Americans counted him as trustworthy.17 And that compulsive dishonesty led directly to January 6, 2021.

In November 2020, Joseph R. Biden, a longtime senator from Delaware and former Vice President under Barack Obama, running alongside Kamala Harris, a California senator who would become the nation’s first female vice president, convincingly defeated Donald Trump at the polls: Biden won the popular vote by a margin of four percent and the electoral vote by a margin of 74 votes, marking the first time an incumbent president had been defeated in over thirty years. But Trump refused to concede the election. He said it had been stolen. He said votes had been manufactured. He said it was all rigged. The claims were easily debunked, but it didn’t seem to matter: months after the election, somewhere between one-half and two-thirds of self-identified Republicans judged the election stolen.18 So when, on the afternoon of January 6, 2021, the president again articulated a litany of lies about the election and told the crowd of angry conspiracy-minded protestors to march to the Capitol and “fight like hell,” they did.

Thousands of Trump’s followers converged on the Capitol. Roughly one in seven of the more than 500 rioters later arrested were affiliated with extremist groups organized around conspiracy theories, white supremacy, and the right-wing militia movement.19 They waved American and Confederate flags, displayed conspiracy theory slogans and white supremacist icons, carried Christian iconography, and, above all, bore flags, hats, shirts, and other emblazoned with the name of Donald Trump.20 Arming themselves for hand-to-hand combat, they pushed past barriers and battled barricaded police officers. The Capitol attackers injured about 150 of them.21 Officers suffered concussions, burns, bruises, stab wounds, and broken bones.22 One suffered a non-fatal heart attack after being shocked repeatedly by a stun gun. Capitol Police Officer Brian D. Sicknick was killed, either by repeated attacks with a fire extinguisher or from mace or bear spray. Four other officers later died by suicide.

As the rioters breached the building, officers inside the House chamber moved furniture to barricade the doors as House members huddled together on the floor, waiting for a breach. Ashli Babbitt, a thirty-five-year-old Air Force veteran consumed by social-media conspiracy theories, and wearing a Trump flag around her neck, was shot and killed by a Capitol Police officer when she attempted to storm the chamber. The House Chamber held, but attackers breached the Senate Chamber on the opposite end of the building. Lawmakers had already been evacuated.

The rioters held the Capitol for several hours before the National Guard cleared it that evening. Congress, refusing to back down, stayed that evening to certify the results of the election. And yet, despite everything that had happened the day, the president’s unfounded claims of election fraud kept their grip on on Republican lawmakers. Eleven Republican senators and 150 of the House’s 212 Republicans lodged objections to the certification. And a little more than a month later, they refused to convict Donald Trump during his quickly organized second impeachment trial, this time for “incitement of insurrection.”

In the winter of 2019 and 2020, a new respiratory virus, Covid-19, emerged in Wuhan, China. It was a coronavirus, named after its spiky, crown-like appearance under a microscope. Other coronaviruses had been identified and contained in previous years, but, by December, Chinese doctors were treating dozens of cases, and, by January, hundreds. Wuhan shut down to contain the outbreak but the virus escaped. By January, the United States confirmed its first case. Deaths were reported in the Philippines and in France. Outbreaks struck Italy and Iran. And American case counts grew. Countries began locking down. Air travel slowed.

The virus was highly contagious and could be spread before the onset of symptoms. Many who had the virus were asymptomatic: they didn’t exhibit any symptoms at all. But others, especially the elderly and those with “co-morbidities,” were struck down. The virus attacked their airways, suffocating them. Doctors didn’t know what they were battling. They struggled to procure oxygen and respirators and incubated the worst cases with what they had. But the deaths piled up.

The virus hit New York City in the spring. The city was devastated. Hospitals overflowed as doctors struggled to treat a disease they barely understood. By April, thousands of patients were dying every day. The city couldn’t keep up with the bodies. Dozens of “mobile morgues” were set up to house bodies which wouldn’t be processed for months.23

With medical-grade masks in short supply, Americans made their own homemade cloth masks. Many right-wing Americans notably refused to wear them at all, further exposing workers and family members to the virus.

Failing to contain the outbreak, the country shut down. Flights stopped. Schools and restaurants closed. White-collar workers transitioned to working from home when offices shut down. But others weren’t so lucky. By April, 10 million Americans had lost their jobs.24

But shutdowns were scattered and incomplete. States were left to fend for themselves, setting their own policies and competing with one another to acquire scarce personal protective equipment (PPE). Many workers couldn’t stay home. Hourly workers, lacking paid sick leave, often had to choose between a paycheck and reporting to work having been exposed or even when presenting symptoms. Mask-wearing, meanwhile, was politicized. By May, 100,000 Americans were dead. A new wave of cases hit the South in July and August, overwhelming hospitals across much of the region. But the worst came in the winter, when the outbreak went fully national. Hundreds of thousands tested positive for the virus every day and nearly three-thousand Americans died every day throughout January and much of February.

The outbreak retreated in the spring, and pharmaceutical labs, flush with federal dollars, released new, cutting-edge vaccines. By late spring, Americans were getting vaccinated by the millions. The virus looked like it could be defeated. But many Americans, variously swayed by conspiracy theories peddled on social media or simply politically radicalized into associating vaccinations with anti-Trump politics, refused them. By late summer, barely a majority of those eligible for vaccines were fully vaccinated. More contagious and elusive strains evolved and spread and the virus continued churning through the population, sending many, especially the elderly, chronically ill, and unvaccinated, to hospitals and to early deaths. By the end of the summer of 2021, according to official counts, over 600,000 Americans had died from Covid-19. By May 2022, the official death toll in the United States crossed one million.

Americans looked anxiously to the future, and yet also, often, to a new generation busy discovering, perhaps, that change was not impossible. Much public commentary in the early twenty-first century concerned “Millennials” and “Generation Z,” the generations that came of age during the new millennium. Commentators, demographers, and political prognosticators continued to ask what the new generation will bring. Time’s May 20, 2013, cover, for instance, read Millennials Are Lazy, Entitled Narcissists Who Still Live with Their Parents: Why They’ll Save Us All. Pollsters focused on features that distinguish millennials from older Americans: millennials, the pollsters said, were more diverse, more liberal, less religious, and wracked by economic insecurity. “They are,” as one Pew report read, “relatively unattached to organized politics and religion, linked by social media, burdened by debt, distrustful of people, in no rush to marry—and optimistic about the future.”25

Millennial attitudes toward homosexuality and gay marriage reflected one of the most dramatic changes in the popular attitudes of recent years. After decades of advocacy, American attitudes shifted rapidly. In 2006, a majority of Americans still told Gallup pollsters that “gay or lesbian relations” was “morally wrong.”26 But prejudice against homosexuality plummeted and greater public acceptance of coming out opened the culture–in 2001, 73 percent of Americans said they knew someone who was gay, lesbian, or bisexual; in 1983, only 24 percent did. Gay characters—and in particular, gay characters with depth and complexity—could be found across the cultural landscape. Attitudes shifted such that, by the 2010s, polls registered majority support for the legalization of gay marriage. A writer for the Wall Street Journal called it “one of the fastest-moving changes in social attitudes of this generation.”27

Such change was, in many respects, a generational one: on average, younger Americans supported gay marriage in higher numbers than older Americans. The Obama administration, meanwhile, moved tentatively. Refusing to push for national interventions on the gay marriage front, Obama did, however, direct a review of Defense Department policies that repealed the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy in 2011. Without the support of national politicians, gay marriage was left to the courts. Beginning in Massachusetts in 2003, state courts had begun slowly ruling against gay marriage bans. Then, in June 2015, the Supreme Court ruled 5–4 in Obergefell v. Hodges that same-sex marriage was a constitutional right. Nearly two thirds of Americans supported the position.28

While liberal social attitudes marked the younger generation, perhaps nothing defined young Americans more than the embrace of technology. The Internet in particular, liberated from desktop modems, shaped more of daily life than ever before. The release of the Apple iPhone in 2007 popularized the concept of smartphones for millions of consumers and, by 2011, about a third of Americans owned a mobile computing device. Four years later, two thirds did.29

Together with the advent of social media, Americans used their smartphones and their desktops to stay in touch with old acquaintances, chat with friends, share photos, and interpret the world—as newspaper and magazine subscriptions dwindled, Americans increasingly turned to their social media networks for news and information.30 Ambitious new online media companies, hungry for clicks and the ad revenue they represented, churned out provocatively titled, easy-to-digest stories that could be linked and tweeted and shared widely among like-minded online communities,31 but even traditional media companies, forced to downsize their newsrooms to accommodate shrinking revenues, fought to adapt to their new online consumers.

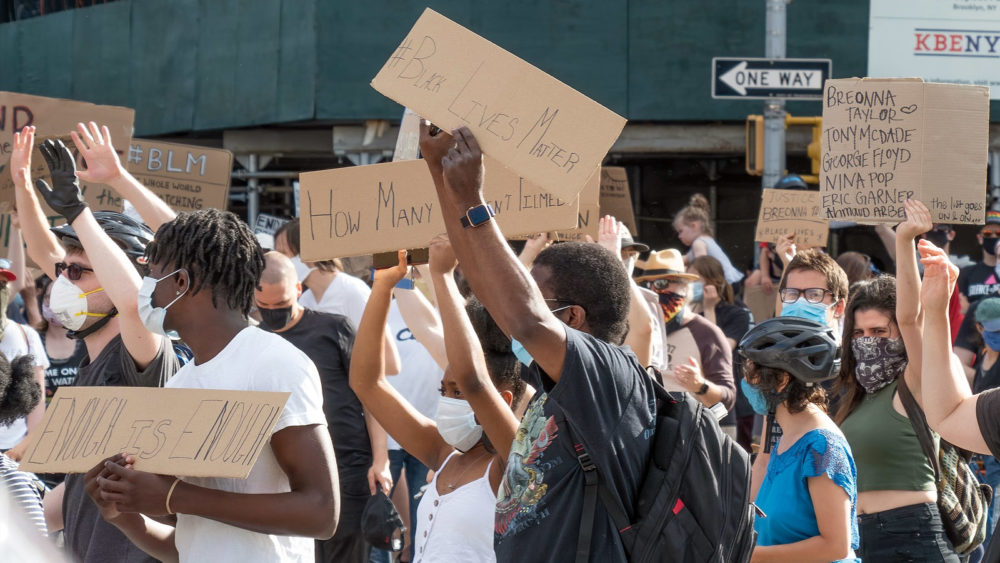

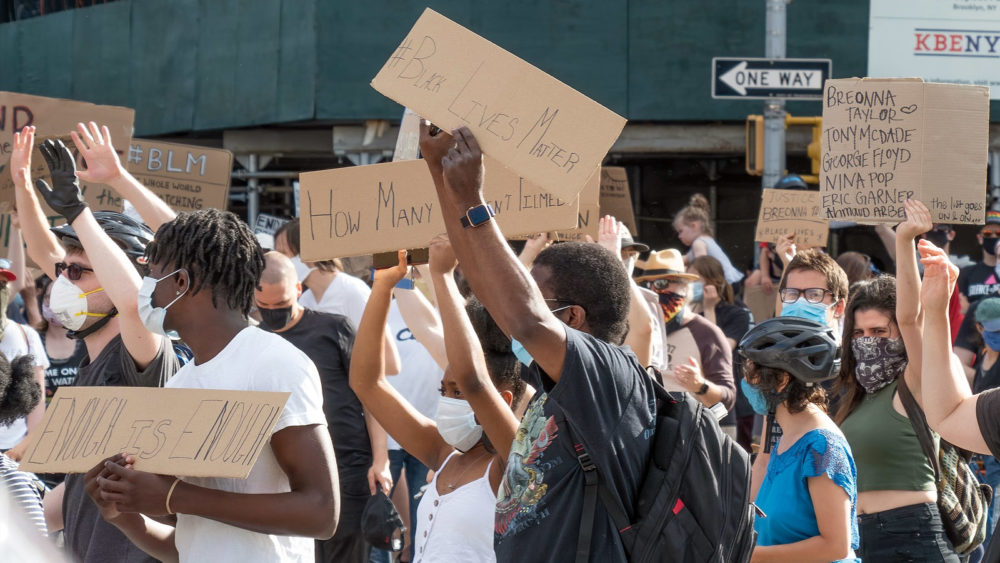

The ability of individuals to share stories through social media apps revolutionized the media landscape—smartphone technology and the democratization of media reshaped political debates and introduced new political questions. The easy accessibility of video capturing and the ability for stories to go viral outside traditional media, for instance, brought new attention to the tense and often violent relations between municipal police officers and African Americans. The 2014 death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, sparked protests and focused the issue. It perhaps became a testament to the power of social media platforms such as Twitter that a hashtag, #blacklivesmatter, became a rallying cry for protesters and counter hashtags, #alllivesmatter and #bluelivesmatter, for critics.32 But a relentless number of videos documenting the deaths of Black men at the hands of police officers continued to circulated across social media networks. The deaths of Eric Garner, twelve-year-old Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, and were captured on cell phone cameras and went viral. So too did the stories of Breonna Taylor and Botham Jean. “Say their names,” a popular chant at Black Lives Matters marches went. And then George Floyd was murdered.

George Floyd’s murder in 2020 sparked the largest protests in American history. Here, crowds holding homemade signs protest in New York City. Via Wikimedia.

On May 25, 2020, a teenager, Darnella Frazier, filmed Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin with his knee on the neck of George Floyd. “I can’t breathe,” Floyd said. Despite his pleas, and those of bystanders, Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck for nine minutes. Floyd’s body had long gone limp. The horrific footage shocked much of the country. Despite state and local lockdowns to slow the spread of Covid-19, spontaneous demonstrations broke out across the country. Protests erupted not only in major cities but in small towns and rural communities. The demonstrations dwarfed, in raw numbers, any comparable protest in American history. Taken together, as many as 25-million Americans may have participated in racial justice demonstrations that summer.33 And yet, despite the marches, no great national policy changes quickly followed. The “system” resisted calls to address “systemic racism.” Localities made efforts, of course. Criminal justice reformers won elections as district attorneys. Police departments mandated their officers carry body cameras. As cries of “defund the police” sounded among left-wing Americans, some cities experimented with alternative emergency services that emphasized mediation and mental health. Meanwhile, at a symbolic level, Democratic-leaning towns and cities in the South pulled down their Confederate iconography. But the intractable racial injustices embedded deeply within American life had not been uprooted and racial disparities in wealth, education, health, and other measures persevered, as they already had, in the United States, for hundreds of years.

As the Black Lives Matter movement captured national attention, another social media phenomenon, the #MeToo movement, began as the magnification of and outrage toward the past sexual crimes of notable male celebrities before injecting a greater intolerance toward those accused of sexual harassment and violence into much of the rest of American society. The sudden zero tolerance reflected the new political energies of many American women, sparked in large part by the candidacy and presidency of Donald Trump. The day after Trump’s inauguration, between five hundred thousand and one million people descended on Washington, D.C., for the Women’s March, and millions more demonstrated in cities and towns around the country to show a broadly defined commitment toward the rights of women and others in the face of the Trump presidency. And with three appointments to the Supreme Court, Donald Trump’s legacy persisted past his presidency. On June 24, 2022, the new conservative majority decided Dobbs v. Jackson, overturning Roe v. Wade (1973) and Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), cases that established a constitutional right to abortion. Meanwhile, other avenues of sexual politics opened across the country. By the 2020s, the broader American culture increasingly featured transgender individuals in media and many Americans began making their preferred pronouns explicit–as well as deploying “they” as a gender-neutral pronoun–to undermine fixed notions of gender. Many conservatives, however, fought back. State legislators around the country sponsored “bathroom bills” to keep transgender individuals out of the bathroom of their identified gender, alleging that they posed a violent sexual risk. In Texas, Attorney General Ken Paxton declared pediatric gender-affirming care to be child abuse.

As issues of race and gender captured much public discussion, immigration continued on as a potent political issue. Even as anti-immigrant initiatives like California’s Proposition 187 (1994) and Arizona’s SB1070 (2010) reflected the anxieties of many white Americans, younger Americans proved far more comfortable with immigration and diversity (which makes sense, given that they are the most diverse American generation in living memory). Since Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society liberalized immigration laws in the 1960s, the demographics of the United States have been transformed. In 2012, nearly one quarter of all Americans were immigrants or the sons and daughters of immigrants. Half came from Latin America. The ongoing Hispanicization of the United States and the ever-shrinking proportion of non-Hispanic whites have been the most talked about trends among demographic observers. By 2013, 17 percent of the nation was Hispanic. In 2014, Latinos surpassed non-Latino whites to become the largest ethnic group in California. In Texas, the image of a white cowboy hardly captures the demographics of a minority-majority state in which Hispanic Texans will soon become the largest ethnic group. For the nearly 1.5 million people of Texas’s Rio Grande Valley, for instance, where most residents speak Spanish at home, a full three fourths of the population is bilingual.34 Political commentators often wonder what political transformations these populations will bring about when they come of age and begin voting in larger numbers.

The collapse of the Soviet Union brought neither global peace nor stability, and the attacks of September 11, 2001, plunged the United States into interminable conflicts around the world. At home, economic recession, a slow recovery, stagnant wage growth, and general pessimism infected American life as contentious politics and cultural divisions poisoned social harmony, leading directly to the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol. And yet the stream of history changes its course. Trends shift, things change, and events turn. New generations bring with them new perspectives, and they share new ideas. Our world is not foreordained. It is the product of history, the ever-evolving culmination of a longer and broader story, of a larger history, of a raw, distinctive, American Yawp.

Notes