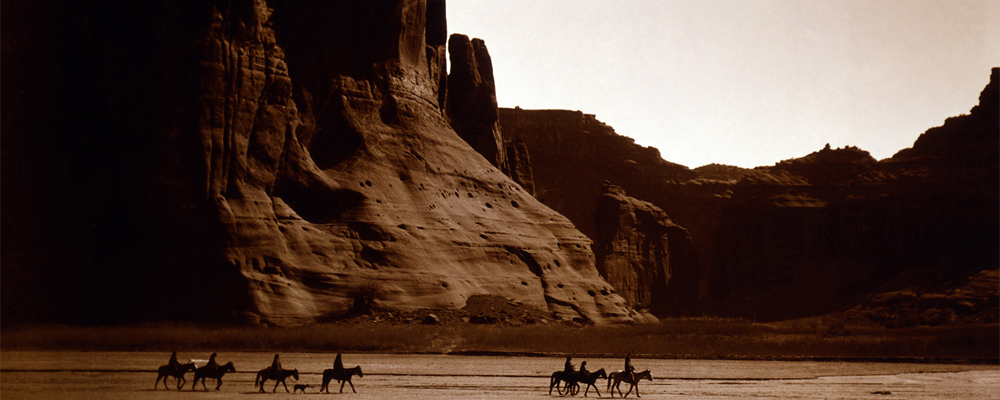

Edward S. Curtis, Navajo Riders in Canyon de Chelly, c1904. Library of Congress.

I. Introduction

Native Americans long dominated the vastness of the American West. Linked culturally and geographically by trade, travel, and warfare, various Indigenous groups controlled most of the continent west of the Mississippi River deep into the nineteenth century. Spanish, French, British, and later American traders had integrated themselves into many regional economies, and American emigrants pushed ever westward, but no imperial power had yet achieved anything approximating political or military control over the great bulk of the continent. But then the Civil War came and went and decoupled the West from the question of slavery just as the United States industrialized and laid down rails and pushed its ever-expanding population ever farther west.

Indigenous Americans have lived in North America for over ten millennia and, into the late nineteenth century, perhaps as many as 250,000 Native people still inhabited the American West.1 But then unending waves of American settlers, the American military, and the unstoppable onrush of American capital conquered all. Often in violation of its own treaties, the United States removed Native groups to ever-shrinking reservations, incorporated the West first as territories and then as states, and, for the first time in its history, controlled the enormity of land between the two oceans.

The history of the late-nineteenth-century West is not a simple story. What some touted as a triumph—the westward expansion of American authority—was for others a tragedy. The West contained many peoples and many places, and their intertwined histories marked a pivotal transformation in the history of the United States.

II. Post-Civil War Westward Migration

In the decades after the Civil War, American settlers poured across the Mississippi River in record numbers. No longer simply crossing over the continent for new imagined Edens in California or Oregon, they settled now in the vast heart of the continent.

Many of the first American migrants had come to the West in search of quick profits during the midcentury gold and silver rushes. As in the California rush of 1848–1849, droves of prospectors poured in after precious-metal strikes in Colorado in 1858, Nevada in 1859, Idaho in 1860, Montana in 1863, and the Black Hills in 1874. While women often performed housework that allowed mining families to subsist in often difficult conditions, a significant portion of the mining workforce were single men without families dependent on service industries in nearby towns and cities. There, working-class women worked in shops, saloons, boardinghouses, and brothels. Many of these ancillary operations profited from the mining boom: as failed prospectors found, the rush itself often generated more wealth than the mines. The gold that left Colorado in the first seven years after the Pikes Peak gold strike—estimated at $25.5 million—was, for instance, less than half of what outside parties had invested in the fever. The 100,000-plus migrants who settled in the Rocky Mountains were ultimately more valuable to the region’s development than the gold they came to find.2

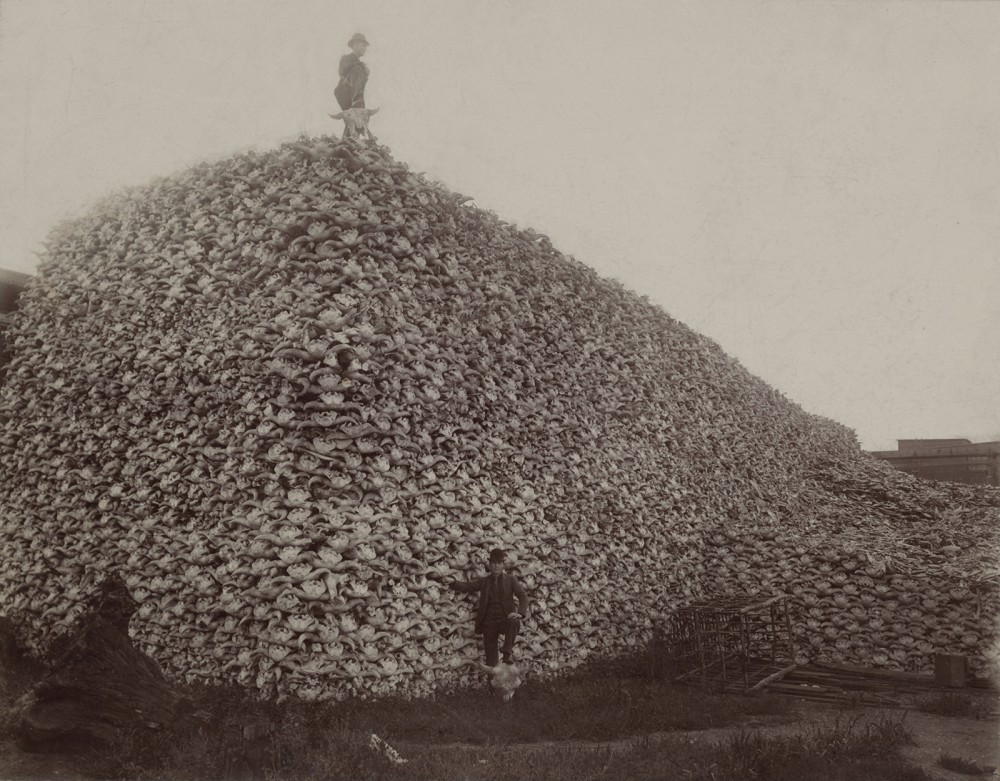

Others came to the Plains to extract the hides of the great bison herds. Millions of animals had roamed the Plains, but their tough leather supplied industrial belting in eastern factories and raw material for the booming clothing industry. Specialized teams took down and skinned the herds. The infamous American bison slaughter peaked in the early 1870s. The number of American bison plummeted from over ten million at midcentury to only a few hundred by the early 1880s. The expansion of the railroads allowed ranching to replace the bison with cattle on the American grasslands.3

While bison supplied leather for America’s booming clothing industry, the skulls of the animals also provided a key ingredient in fertilizer. This 1870s photograph illustrates the massive number of bison killed for these and other reasons (including sport) in the second half of the nineteenth century. Photograph of a pile of American bison skulls waiting to be ground for fertilizer, 1870s. Wikimedia.

The nearly seventy thousand members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (more commonly called Mormons) who migrated west between 1846 and 1868 were similar to other Americans traveling west on the overland trails. They faced many of the same problems, but unlike most other American migrants, Mormons were fleeing from religious persecution.

Many historians view Mormonism as a “uniquely American faith,” not just because it was founded by Joseph Smith in New York in the 1830s, but because of its optimistic and future-oriented tenets. Mormons believed that Americans were exceptional—chosen by God to spread truth across the world and to build utopia, a New Jerusalem in North America. However, many Americans were suspicious of the Latter-Day Saint movement and its unusual rituals, especially the practice of polygamy, and most Mormons found it difficult to practice their faith in the eastern United States. Thus began a series of migrations in the midnineteenth century, first to Illinois, then Missouri and Nebraska, and finally into Utah Territory.

Once in the west, Mormon settlements served as important supply points for other emigrants heading on to California and Oregon. Brigham Young, the leader of the Church after the death of Joseph Smith, was appointed governor of the Utah Territory by the federal government in 1850. He encouraged Mormon residents of the territory to engage in agricultural pursuits and be cautious of the outsiders who arrived as the mining and railroad industries developed in the region.4

It was land, ultimately, that drew the most migrants to the West. Family farms were the backbone of the agricultural economy that expanded in the West after the Civil War. In 1862, northerners in Congress passed the Homestead Act, which allowed male citizens (or those who declared their intent to become citizens) to claim federally owned lands in the West. Settlers could head west, choose a 160-acre surveyed section of land, file a claim, and begin “improving” the land by plowing fields, building houses and barns, or digging wells, and, after five years of living on the land, could apply for the official title deed to the land. Hundreds of thousands of Americans used the Homestead Act to acquire land. The treeless plains that had been considered unfit for settlement became the new agricultural mecca for land-hungry Americans.5

The Homestead Act excluded married women from filing claims because they were considered the legal dependents of their husbands. Some unmarried women filed claims on their own, but single farmers (male or female) were hard-pressed to run a farm and they were a small minority. Most farm households adopted traditional divisions of labor: men worked in the fields and women managed the home and kept the family fed. Both were essential.6

Migrants sometimes found in homesteads a self-sufficiency denied at home. Second or third sons who did not inherit land in Scandinavia, for instance, founded farm communities in Minnesota, Dakota, and other Midwestern territories in the 1860s. Boosters encouraged emigration by advertising the semiarid Plains as, for instance, “a flowery meadow of great fertility clothed in nutritious grasses, and watered by numerous streams.”7 Western populations exploded. The Plains were transformed. In 1860, for example, Kansas had about 10,000 farms; in 1880 it had 239,000. Texas saw enormous population growth. The federal government counted 200,000 people in Texas in 1850, 1,600,000 in 1880, and 3,000,000 in 1900, making it the sixth most populous state in the nation.

III. The Indian Wars and Federal Peace Policies

The “Indian wars,” so mythologized in western folklore, were a series of seemingly sporadic, localized, and often brief engagements between U.S. military forces and various Native American groups. More sustained and equally impactful conflicts were economic and cultural. New patterns of American settlement, railroad construction, and material extraction clashed with the vast and cyclical movement across the Great Plains to hunt buffalo, raid enemies, and trade goods. Thomas Jefferson’s old dream that Indigenous nations might live isolated in the West was, in the face of American expansion, no longer a viable reality. Political, economic, and even humanitarian concerns intensified American efforts to isolate Native Americans on reservations. Although Indian removal had long been a part of federal Indian policy, following the Civil War the U.S. government redoubled its efforts. If treaties and other forms of persistent coercion would not work, federal officials pushed for more drastic measures: after the Civil War, coordinated military action by celebrity Civil War generals such as William Sherman and William Sheridan exploited and exacerbated local conflicts sparked by illegal business ventures and settler incursions. Against the threat of confinement and the extinction of traditional ways of life, Native Americans battled the American army and the encroaching lines of American settlement.

In one of the earliest western engagements, in 1862, while the Civil War still consumed the United States, tensions erupted between Dakota Nation and white settlers in Minnesota and the Dakota Territory. The 1850 U.S. census recorded a white population of about 6,000 in Minnesota; eight years later, when it became a state, it was more than 150,000.8 The illegal influx of American farmers pushed the Dakota to the breaking point. Hunting became unsustainable and those Dakota who had taken up farming found only poverty. The federal Indian agent refused to disburse promised food. Many starved. Andrew Myrick, a trader at the agency, refused to sell food on credit. “If they are hungry,” he is alleged to have said, “let them eat grass or their own dung.” Then, on August 17, 1862, four young men of the Santees, a Dakota band, killed five white settlers near the Redwood Agency, an American administrative office. In the face of an inevitable American retaliation, and over the protests of many members, the tribe chose war. On the following day, Dakota warriors attacked settlements near the Agency. They killed thirty-one men, women, and children (including Myrick, whose mouth was found filled with grass). They then ambushed a U.S. military detachment at Redwood Ferry, killing twenty-three. The governor of Minnesota called up militia and several thousand Americans waged war against the Indigenous insurgents. Fighting broke out at New Ulm, Fort Ridgely, and Birch Coulee, but the Americans broke Indigenous resistance at the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, ending the so-called Dakota War.9

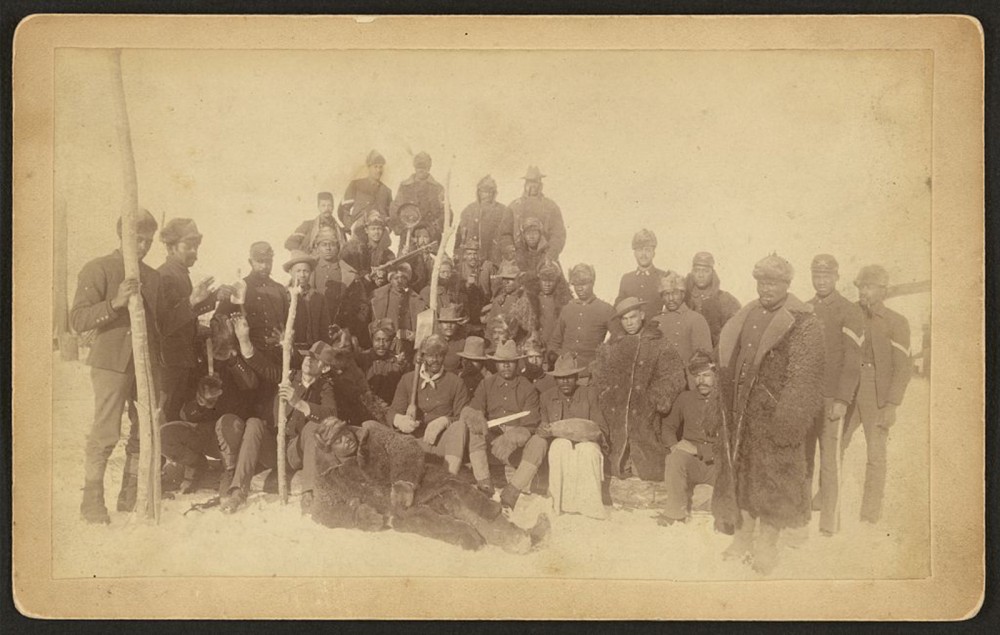

Buffalo Soldiers, the nickname given to African-American cavalrymen by the native Americans they fought, were the first peacetime all-black regiments in the regular United States army. These soldiers regularly confronted racial prejudice from other Army members and civilians but were an essential part of American victories during the Indian Wars of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. “[Buffalo soldiers of the 25th Infantry, some wearing buffalo robes, Ft. Keogh, Montana] / Chr. Barthelmess, photographer, Fort Keogh, Montana,” 1890. Library of Congress.

More than two thousand Dakota had been taken prisoner during the fighting. Many were tried at federal forts for murder, rape, and other atrocities, in a kind of legalistic choreography that conveyed American ideas of Native guilt and white innocence. Military tribunals convicted 303 Dakota and sentenced them to hang. At the last minute, President Lincoln commuted all but thirty-eight of the sentences. Minnesota settlers and government officials insisted not only that the Dakota lose much of their reservation lands and be removed farther west, but that those who had fled be hunted down and placed on reservations as well. The American military gave chase and, on September 3, 1863, after a year of attrition, American military units surrounded a large encampment of Dakota. American troops killed an estimated three hundred men, women, and children. Dozens more were taken prisoner. Troops spent the next two days burning winter food and supply stores to starve out the Dakota resistance, which continued to insist on Dakota sovereignty and treaty rights.Farther south, settlers inflamed tensions in Colorado. In 1851, the first Treaty of Fort Laramie had secured right-of-way access for Americans passing through on their way to California and Oregon. But a gold rush in 1858 drew approximately 100,000 white gold seekers, and they demanded new treaties be made with local Indigenous groups to secure land rights in the newly created Colorado Territory. Cheyenne bands splintered over the possibility of signing a new treaty that would confine them to a reservation. Settlers, already wary of raids by powerful groups of Cheyennes, Arapahos, and Comanches, meanwhile read in their local newspapers sensationalist accounts of the uprising in Minnesota. Militia leader John M. Chivington warned settlers in the summer of 1864 that the Cheyenne were dangerous, urged war, and promised a swift military victory. Settlers sparked conflict and sporadic fighting broke out. The aged Cheyenne chief Black Kettle, believing that a peace treaty would be best for his people, traveled to Denver to arrange for peace talks. He and his followers traveled toward Fort Lyon in accordance with government instructions, but on November 29, 1864, Chivington ordered his seven hundred militiamen to move on the Cheyenne camp near Fort Lyon at Sand Creek. The Cheyenne tried to declare their peaceful intentions but Chivington’s militia cut them down. It was a slaughter. Chivington’s men killed two hundred men, women, and children.10 The Sand Creek Massacre was a national scandal, alternately condemned and applauded.

As settler incursions continued to provoke conflict, Americans pushed for a new “peace policy.” Congress, confronted with these tragedies and further violence, authorized in 1868 the creation of an Indian Peace Commission. The commission’s study of Native Americans decried prior American policy and galvanized support for reformers. After the inauguration of Ulysses S. Grant the following spring, Congress allied with prominent philanthropists to create the Board of Indian Commissioners, a permanent advisory body to oversee Indigenous affairs and prevent the further outbreak of violence. The board effectively Christianized American Indian policy. Much of the reservation system was handed over to Protestant churches, which were tasked with finding agents and missionaries to manage reservation life. Congress hoped that religiously minded men might fare better at creating just assimilation policies and persuading Native Americans to accept them. Historian Francis Paul Prucha believed that this attempt at a new “peace policy . . . might just have properly been labelled the ‘religious policy.’”11

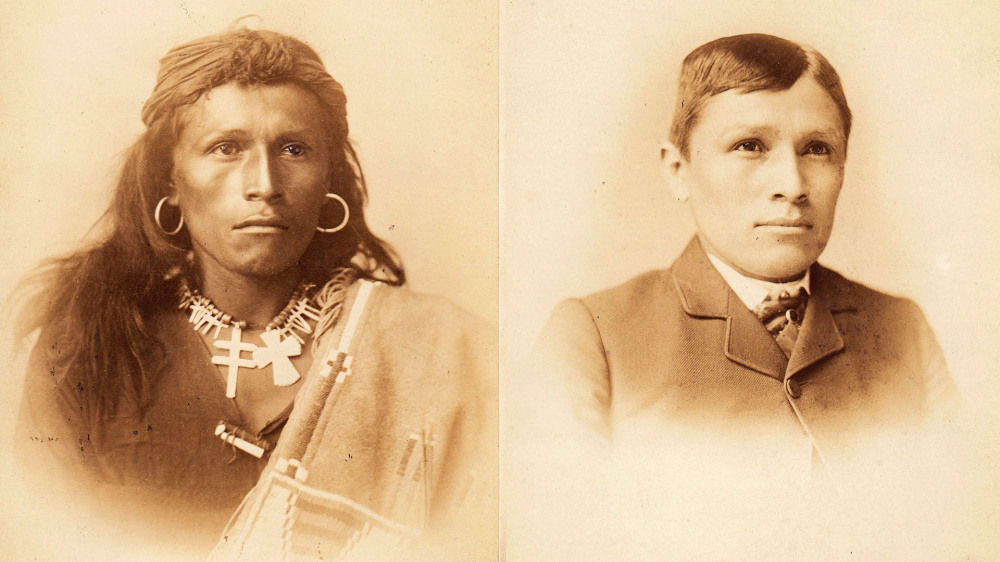

Tom Torlino, a member of the Navajo Nation, entered the Carlisle Indian School, a Native American boarding school founded by the United States government in 1879, on October 21, 1882 and departed on August 28, 1886. Torlino’s student file contained photographs from 1882 and 1885. Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

Many female Christian missionaries played a central role in cultural reeducation programs that attempted to not only instill Protestant religion but also impose traditional American gender roles and family structures. They endeavored to replace Indigenous peoples’ tribal social units with small, patriarchal households. Women’s labor became a contentious issue because few tribes divided labor according to the gender norms of middle- and upper-class Americans. Fieldwork, the traditional domain of white males, was primarily performed by Native women, who also usually controlled the products of their labor, if not the land that was worked, giving them status in society as laborers and food providers. For missionaries, the goal was to get Native women to leave the fields and engage in more proper “women’s” work—housework. Christian missionaries performed much as secular federal agents had. Few American agents could meet Native Americans on their own terms. Most Americans viewed Indigenous peoples on reservations as lazy and thought of Indigenous cultures as inferior to their own. The views of J. L. Broaddus, appointed to oversee several small tribes on the Hoopa Valley reservation in California, are illustrative: in his annual report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for 1875, he wrote, “The great majority of them are idle, listless, careless, and improvident. They seem to take no thought about provision for the future, and many of them would not work at all if they were not compelled to do so. They would rather live upon the roots and acorns gathered by their women than to work for flour and beef.”12

If Indigenous peoples could not be forced through kindness to change their ways, most Americans agreed that it was acceptable to use force, which Native groups resisted. In Texas and the Southern Plains, the Comanche, the Kiowa, and their allies had wielded enormous influence. The Comanche in particular controlled huge swaths of territory and raided vast areas, inspiring terror from the Rocky Mountains to the interior of northern Mexico to the Texas Gulf Coast. But after the Civil War, the U.S. military refocused its attention on the Southern Plains.

The American military first sent messengers to the Plains to find the elusive Comanche bands and ask them to come to peace negotiations at Medicine Lodge Creek in the fall of 1867. But terms were muddled: American officials believed that Comanche bands had accepted reservation life, while Comanche leaders believed they were guaranteed vast lands for buffalo hunting. Comanche bands used designated reservation lands as a base from which to collect supplies and federal annuity goods while continuing to hunt, trade, and raid American settlements in Texas.

Confronted with renewed Comanche raiding, particularly by the famed war leader Quanah Parker, the U.S. military finally proclaimed that all Indigenous peoples who were not settled on the reservation by the fall of 1874 would be considered “hostile.” The Red River War began when many Comanche bands refused to resettle and the American military launched expeditions into the Plains to subdue them, culminating in the defeat of the remaining roaming bands in the canyonlands of the Texas Panhandle. Cold and hungry, with their way of life already decimated by soldiers, settlers, cattlemen, and railroads, the last free Comanche bands were moved to the reservation at Fort Sill, in what is now southwestern Oklahoma.13

On the northern Plains, the Sioux people had yet to fully surrender. Following the military defeats of 1862, many bands had signed treaties with the United States and drifted into the Red Cloud and Spotted Tail agencies to collect rations and annuities, but many continued to resist American encroachment, particularly during Red Cloud’s War, a rare victory for the Plains people that resulted in the Treaty of 1868 and created the Great Sioux Reservation. Then, in 1874, an American expedition to the Black Hills of South Dakota discovered gold. White prospectors flooded the territory. Caring very little about Indigenous rights and very much about getting rich, they brought the Sioux situation again to its breaking point. Aware that U.S. citizens were violating treaty provisions, but unwilling to prevent them from searching for gold, federal officials pressured the western Sioux to sign a new treaty that would transfer control of the Black Hills to the United States while General Philip Sheridan quietly moved U.S. troops into the region. Initial clashes between U.S. troops and Sioux warriors resulted in several Sioux victories that, combined with the visions of Sitting Bull, who had dreamed of an even more triumphant victory, attracted Sioux bands who had already signed treaties but now joined to fight.14

In late June 1876, a division of the 7th Cavalry Regiment led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer was sent up a trail into the Black Hills as an advance guard for a larger force. Custer’s men approached a camp along a river known to the Sioux as Greasy Grass but marked on Custer’s map as Little Bighorn, and they found that the influx of “treaty” Sioux as well as aggrieved Cheyenne and other allies had swelled the population of the village far beyond Custer’s estimation. Custer’s 7th Cavalry was vastly outnumbered, and he and 268 of his men were killed.15

Custer’s fall shocked the nation. Cries for a swift American response filled the public sphere, and military expeditions were sent out to crush Native resistance. The Sioux splintered off into the wilderness and began a campaign of intermittent resistance but, outnumbered and suffering after a long, hungry winter, Crazy Horse led a band of Oglala Sioux to surrender in May 1877. Other bands gradually followed until finally, in July 1881, Sitting Bull and his followers at last laid down their weapons and came to the reservation. Indigenous powers had been defeated. The Plains, it seemed, had been pacified.

IV. Beyond the Plains

Plains peoples were not the only ones who suffered as a result of American expansion. Groups like the Utes and Paiutes were pushed out of the Rocky Mountains by U.S. expansion into Colorado and away from the northern Great Basin by the expanding Mormon population in Utah Territory in the 1850s and 1860s. Faced with a shrinking territorial base, members of these two groups often joined the U.S. military in its campaigns in the southwest against other powerful Native groups like the Hopi, the Zuni, the Jicarilla Apache, and especially the Navajo, whose population of at least ten thousand engaged in both farming and sheep herding on some of the most valuable lands acquired by the United States after the Mexican War.

Conflicts between the U.S. military, American settlers, and Native nations increased throughout the 1850s. By 1862, General James Carleton began searching for a reservation where he could remove the Navajo and end their threat to U.S. expansion in the Southwest. Carleton selected a dry, almost treeless site in the Bosque Redondo Valley, three hundred miles from the Navajo homeland.

In April 1863, Carleton gave orders to Colonel Kit Carson to round up the entire Navajo population and escort them to Bosque Redondo. Those who resisted would be shot. Thus began a period of Navajo history called the Long Walk, which remains deeply important to Navajo people today. The Long Walk was not a single event but a series of forced marches to the reservation at Bosque Redondo between August 1863 and December 1866. Conditions at Bosque Redondo were horrible. Provisions provided by the U.S. Army were not only inadequate but often spoiled; disease was rampant, and thousands of Navajos died.

By 1868, it had become clear that life at the reservation was unsustainable. General William Tecumseh Sherman visited the reservation and wrote of the inhumane situation in which the Navajo were essentially kept as prisoners, but lack of cost-effectiveness was the main reason Sherman recommended that the Navajo be returned to their homeland in the West. On June 1, 1868, the Navajo signed the Treaty of Bosque Redondo, an unprecedented treaty in the history of U.S.-Native relations in which the Navajo were able to return from the reservation to their homeland.

The attacks on Native nations in California and the Pacific Northwest received significantly less attention than the dramatic conquest of the Plains, but Native peoples in these regions also experienced violence, population decline, and territorial loss. For example, in 1872, the California/Oregon border erupted in violence when the Modoc people left the reservation of the Klamath Nation, onto which they had been forced, and returned to their homelands in an area known as Lost River. Americans had settled the region after Modoc removal several years before, and they complained bitterly of the Natives’ return. The U.S. military arrived when fifty-two remaining Modoc warriors, led by Kintpuash, known to settlers as Captain Jack, refused to return to the reservation and holed up in defensive positions along the state border. They fought a guerrilla war for eleven months in which at least two hundred U.S. troops were killed before they were finally forced to surrender. Despite appeals from settlers acquainted with the Modoc, the federal government hanged Kintpuash and three others leaders in a highly choreographed and publicized public execution.16

Four years later, in the Pacific Northwest, a branch of the Nez Perce (who, generations earlier, had aided Lewis and Clark in their famous journey to the Pacific Ocean) refused to be moved to a reservation and, under the leadership of Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt, known to settlers and American readers as Chief Joseph, attempted to flee to Canada but were pursued by the U.S. Cavalry. The outnumbered Nez Perce battled across a thousand miles and were attacked nearly two dozen times before they succumbed to hunger and exhaustion, surrendered, were imprisoned, and removed to a reservation in Indian Territory. The flight of the Nez Perce captured the attention of the United States, and a transcript of Chief Joseph’s surrender, as allegedly recorded by a U.S. Army officer, became a landmark of American rhetoric. “Hear me, my chiefs,” Joseph was supposed to have said, “I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.” Chief Joseph used his celebrity, and, after several years, negotiated his people’s relocation to a reservation nearer to their historic home.17

The treaties that had been signed with numerous Native nations in California in the 1850s were never ratified by the Senate. Over one hundred distinct Native groups lived in California before the Spanish and American conquests, but by 1880, the Native population of California had collapsed from about 150,000 on the eve of the gold rush to a little less than 20,000. A few reservation areas were eventually set up by the U.S. government to collect what remained of the Native population, but most were dispersed throughout California. This was partly the result of state laws from the 1850s that allowed white Californians to obtain both Native children and adults as “apprentice” laborers by merely bringing the desired laborer before a judge and promising to feed, clothe, and eventually release them after a period of “service” that ranged from ten to twenty years. Thousands of California’s Natives were thus pressed into a form of slave labor that supported the growing mining, agricultural, railroad, and cattle industries.

V. Western Economic Expansion: Railroads and Cattle

Aside from agriculture and the extraction of natural resources—such as timber and precious metals—two major industries fueled the new western economy: ranching and railroads. Both developed in connection with each other, accelerated the inrush of settlers displacing Native peoples out, and shaped the collective American memory of the post–Civil War “Wild West.”

As one booster put it, “the West is purely a railroad enterprise.” No economic enterprise rivaled the railroads in scale, scope, or sheer impact. No other businesses had attracted such enormous sums of capital, and no other ventures ever received such lavish government subsidies (business historian Alfred Chandler called the railroads the “first modern business enterprise”).18 By “annihilating time and space”—by connecting the vastness of the continent—the railroads transformed the United States and made the American West.

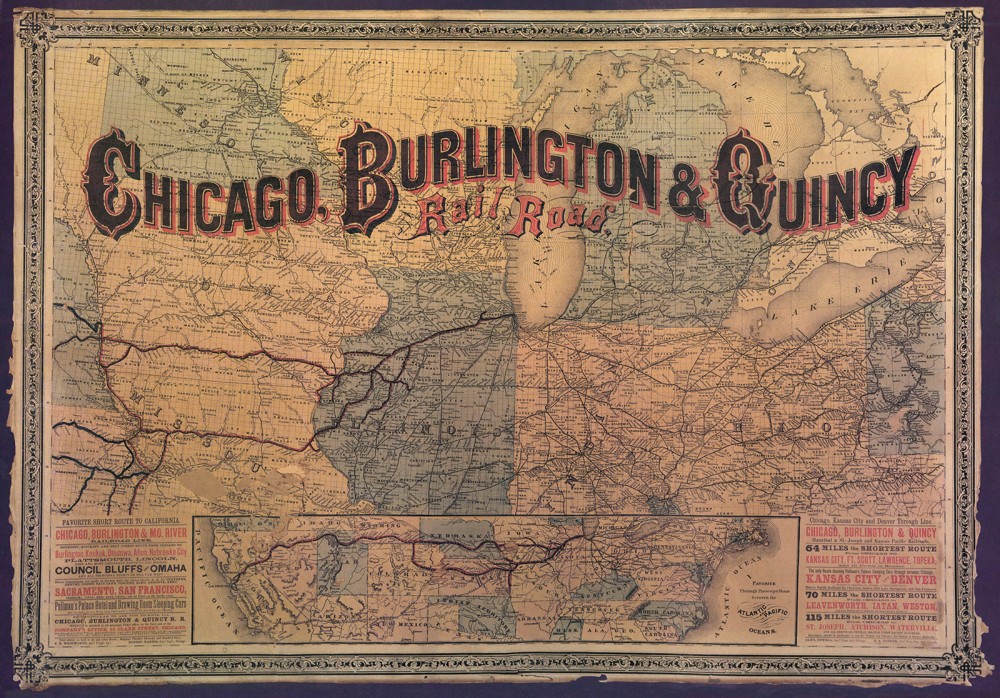

Railroads made the settlement and growth of the West possible. By the late nineteenth century, maps of the Midwest were filled with advertisements touting how quickly a traveler could traverse the country. The Environment and Society Portal, a digital project from the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, a joint initiative of LMU Munich and the Deutsches Museum.

No railroad enterprise so captured the American imagination—or federal support—as the transcontinental railroad. The transcontinental railroad crossed western plains and mountains and linked the West Coast with the rail networks of the eastern United States. Constructed from the west by the Central Pacific and from the east by the Union Pacific, the two roads were linked in Utah in 1869 to great national fanfare. But such a herculean task was not easy, and national legislators threw enormous subsidies at railroad companies, a part of the Republican Party platform since 1856. The 1862 Pacific Railroad Act gave bonds of between $16,000 and $48,000 for each mile of construction and provided vast land grants to railroad companies. Between 1850 and 1871 alone, railroad companies received more than 175,000,000 acres of public land, an area larger than the state of Texas. Investors reaped enormous profits. As one congressional opponent put it in the 1870s, “If there be profit, the corporations may take it; if there be loss, the Government must bear it.”19

If railroads attracted unparalleled subsidies and investments, they also created enormous labor demands. By 1880, approximately four hundred thousand men—or nearly 2.5 percent of the nation’s entire workforce—labored in the railroad industry. Much of the work was dangerous and low-paying, and companies relied heavily on immigrant labor to build tracks. Companies employed Irish workers in the early nineteenth century and Chinese workers in the late nineteenth century. By 1880, over two hundred thousand Chinese migrants lived in the United States. Once the rails were laid, companies still needed a large workforce to keep the trains running. Much railroad work was dangerous, but perhaps the most hazardous work was done by brakemen. Before the advent of automatic braking, an engineer would blow the “down brake” whistle and brakemen would scramble to the top of the moving train, regardless of the weather conditions, and run from car to car manually turning brakes. Speed was necessary, and any slip could be fatal. Brakemen were also responsible for coupling the cars, attaching them together with a large pin. It was easy to lose a hand or finger and even a slight mistake could cause cars to collide.20

The railroads boomed. In 1850, there were 9,000 miles of railroads in the United States. In 1900 there were 190,000, including several transcontinental lines.21 To manage these vast networks of freight and passenger lines, companies converged rails at hub cities. Of all the Midwestern and western cities that blossomed from the bridging of western resources and eastern capital in the late nineteenth century, Chicago was the most spectacular. It grew from two hundred inhabitants in 1833 to over a million by 1890. By 1893 it and the region from which it drew were completely transformed. The World’s Columbian Exposition that year trumpeted the city’s progress and broader technological progress, with typical Gilded Age ostentation. A huge, gleaming (but temporary) “White City” was built in neoclassical style to house all the features of the fair and cater to the needs of the visitors who arrived from all over the world. Highlighted in the title of this world’s fair were the changes that had overtaken North America since Columbus made landfall four centuries earlier. Chicago became the most important western hub and served as the gateway between the farm and ranch country of the Great Plains and eastern markets. Railroads brought cattle from Texas to Chicago for slaughter, where they were then processed into packaged meats and shipped by refrigerated rail to New York City and other eastern cities. Such hubs became the central nodes in a rapid-transit economy that increasingly spread across the entire continent linking goods and people together in a new national network.

This national network created the fabled cattle drives of the 1860s and 1870s. The first cattle drives across the central Plains began soon after the Civil War. Railroads created the market for ranching, and for the few years after the war that railroads connected eastern markets with important market hubs such as Chicago, but had yet to reach Texas ranchlands, ranchers began driving cattle north, out of the Lone Star state, to major railroad terminuses in Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska. Ranchers used well-worn trails, such as the Chisholm Trail, for drives, but conflicts arose with Native Americans in the Indian Territory and farmers in Kansas who disliked the intrusion of large and environmentally destructive herds onto their own hunting, ranching, and farming lands. Other trails, such as the Western Trail, the Goodnight-Loving Trail, and the Shawnee Trail, were therefore blazed.

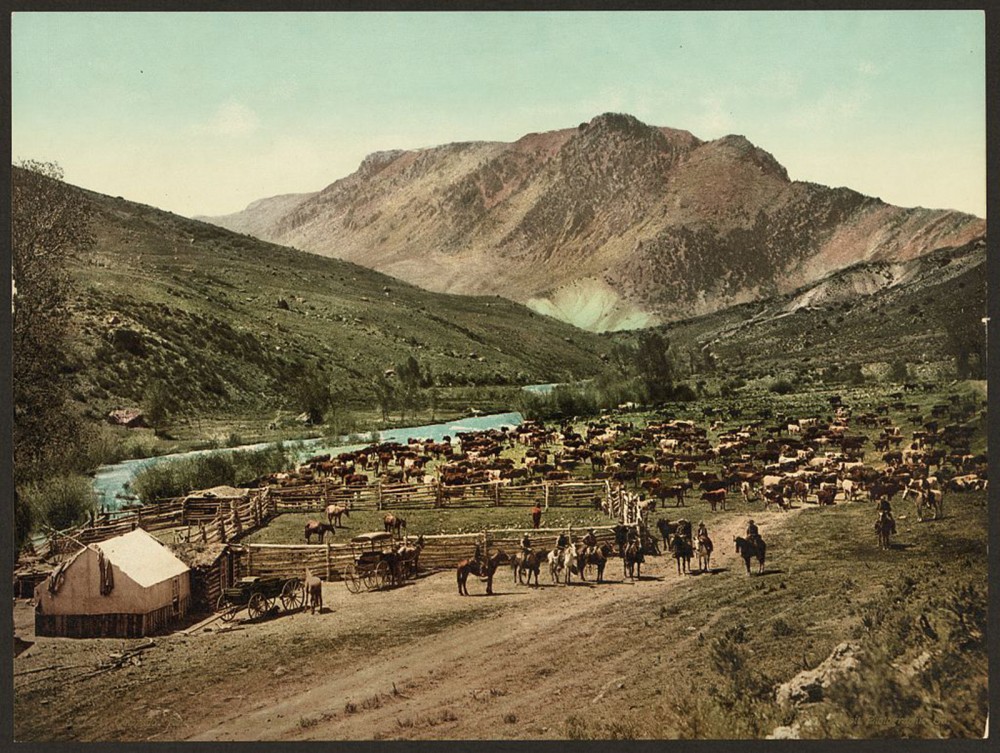

This photochrom print (a new technology in the late nineteenth century that colorized images from a black-and-white negative) depicts a cattle round-up in Cimarron, a crossroads of the late nineteenth-century cattle drives. Detroit Photographic Co., “Colorado. ‘Round up’ on the Cimarron,” c. 1898. Library of Congress.

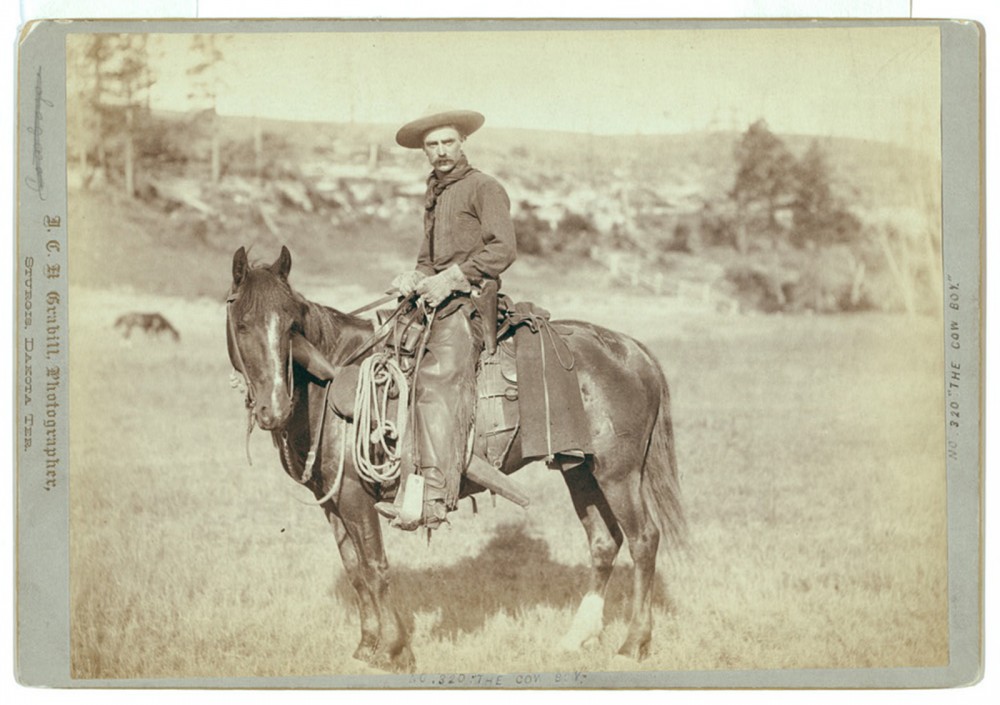

Cattle drives were difficult tasks for the crews of men who managed the herds. Historians estimate the number of men who worked as cowboys in the late-nineteenth century to be between twelve thousand and forty thousand. Perhaps a fourth were African American, and more were likely Mexican or Mexican American. Much about the American cowboys evolved from Mexican vaqueros: cowboys adopted Mexican practices, gear, and terms such as rodeo, bronco, and lasso.”

While most cattle drivers were men, there are at least sixteen verifiable accounts of women participating in the drives. Some, like Molly Dyer Goodnight, accompanied their husbands. Others, like Lizzie Johnson Williams, helped drive their own herds. Williams made at least three known trips with her herds up the Chisholm Trail.

Many cowboys hoped one day to become ranch owners themselves, but employment was insecure and wages were low. Beginners could expect to earn around $20–$25 per month, and those with years of experience might earn $40–$45. Trail bosses could earn over $50 per month. And it was tough work. On a cattle drive, cowboys worked long hours and faced extremes of heat and cold and intense blowing dust. They subsisted on limited diets with irregular supplies.22

Cowboys like the one pictured here worked the drives that supplied Chicago and other mid-western cities with the necessary cattle to supply and help grow the meat-packing industry. Their work was obsolete by the turn of the century, yet their image lived on through vaudeville shows and films that romanticized life in the West. John C.H. Grabill, “The Cow Boy,” c. 1888. Library of Congress.

But if workers of cattle earned low wages, owners and investors could receive riches. At the end of the Civil War, a steer worth $4 in Texas could fetch $40 in Kansas. Although profits slowly leveled off, large profits could still be made. And yet, by the 1880s, the great cattle drives were largely done. The railroads had created them, and the railroads ended them: railroad lines pushed into Texas and made the great drives obsolete. But ranching still brought profits and the Plains were better suited for grazing than for agriculture, and western ranchers continued supplying beef for national markets.

Ranching was just one of many western industries that depended on the railroads. By linking the Plains with national markets and rapidly moving people and goods, the railroads made the modern American West.

VI. The Allotment Era and Resistance in the Native West

As the rails moved into the West, and more and more Americans followed, the situation for Native groups deteriorated even further. Treaties negotiated between the United States and Native groups had typically promised that if tribes agreed to move to specific reservation lands, they would hold those lands collectively. But as American westward migration mounted and open lands closed, white settlers began to argue that Native people had more than their fair share of land, that the reservations were too big, that Native people were using the land “inefficiently,” and that they still preferred nomadic hunting instead of intensive farming and ranching.

By the 1880s, Americans increasingly championed legislation to allow the transfer of Indigenous lands to farmers and ranchers, while many argued that allotting land to individual Native Americans, rather than to tribes, would encourage American-style agriculture and finally put Indigenous peoples who had previously resisted the efforts of missionaries and federal officials on the path to “civilization.”

Passed by Congress on February 8, 1887, the Dawes General Allotment Act splintered Native American reservations into individual family homesteads. Each head of a Native family was to be allotted 160 acres, the typical size of a claim that any settler could establish on federal lands under the provisions of the Homestead Act. Single individuals over age eighteen would receive an eighty-acre allotment, and orphaned children received forty acres. A four-year timeline was established for Indigenous peoples to make their allotment selections. If at the end of that time no selection had been made, the act authorized the secretary of the interior to appoint an agent to make selections for the remaining tribal members. Allegedly to protect Native Americans from being swindled by unscrupulous land speculators, all allotments were to be held in trust—they could not be sold by allottees—for twenty-five years. Lands that remained unclaimed by tribal members after allotment would revert to federal control and be sold to American settlers.23

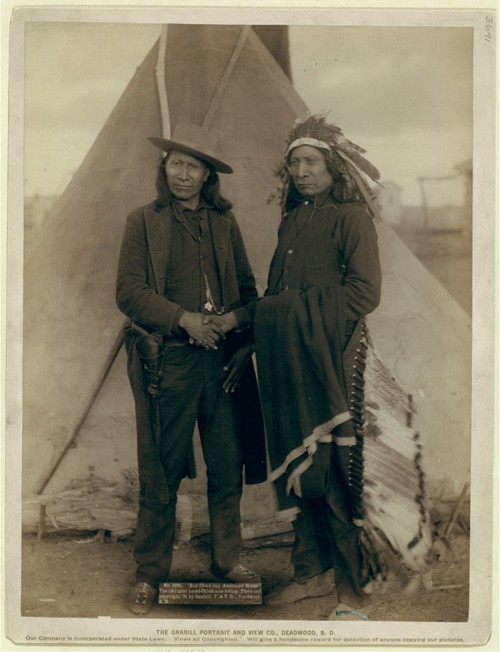

Red Cloud and American Horse – two of the most renowned Ogala chiefs – are seen clasping hands in front of a tipi on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Both men served as delegates to Washington, D.C., after years of actively fighting the American government. John C. Grabill, “‘Red Cloud and American Horse.’ The two most noted chiefs now living,” 1891. Library of Congress.

Americans touted the Dawes Act as an uplifting humanitarian reform, but it upended Native lifestyles and left Native nations without sovereignty over their lands. The act claimed that to protect Native property rights, it was necessary to extend “the protection of the laws of the United States . . . over the Indians.” Tribal governments and legal principles could be superseded, or dissolved and replaced, by U.S. laws. Under the terms of the Dawes Act, Native nations struggled to hold on to some measure of tribal sovereignty.

The stresses of conquest unsettled generations of Native Americans. Many took comfort from the words of prophets and holy men. In Nevada, on January 1, 1889, Northern Paiute prophet Wovoka experienced a great revelation. He had traveled, he said, from his earthly home in western Nevada to heaven and returned during a solar eclipse to prophesy to his people. “You must not hurt anybody or do harm to anyone. You must not fight. Do right always,” he allegedly exhorted. And they must, he said, participate in a religious ceremony that came to be known as the Ghost Dance. If the people lived justly and danced the Ghost Dance, Wovoka said, their ancestors would rise from the dead, droughts would dissipate, the whites in the West would vanish, and the buffalo would once again roam the Plains.24

Native American prophets had often confronted American imperial power. Some prophets, including Wovoka, incorporated Christian elements like heaven and a Messiah figure into Indigenous spiritual traditions. And so, though it was far from unique, Wovoka’s prophecy nevertheless caught on quickly and spread beyond the Paiutes. From across the West, members of the Arapaho, Bannock, Cheyenne, and Shoshone nations, among others, adopted the Ghost Dance religion. Perhaps the most avid Ghost Dancers—and certainly the most famous—were the Lakota Sioux.

The Lakota were in dire straits. South Dakota, formed out of land that belonged by treaty to the Lakota, became a state in 1889. White homesteaders had poured in, reservations were carved up and diminished, starvation set in, corrupt federal agents cut food rations, and drought hit the Plains. Many Lakota feared a future as the landless subjects of a growing American empire when a delegation of eleven men, led by Kicking Bear, joined Ghost Dance pilgrims on the rails westward to Nevada and returned to spread the revival in the Dakotas.

The energy and message of the revivals frightened settlers and Indian agents. Newly arrived Pine Ridge agent Daniel Royer sent fearful dispatches to Washington and the press urging a military crackdown. Newspapers, meanwhile, sensationalized the Ghost Dance.25 Agents began arresting Lakota leaders. Chief Sitting Bull and several others were killed in December 1890 during a botched arrest, convincing many bands to flee the reservations to join fugitive bands farther west, where Lakota adherents of the Ghost Dance preached that the Ghost Dancers would be immune to bullets.

Two weeks later, an American cavalry unit intercepted a band of 350 Lakotas, including over 100 women and children, under Chief Spotted Elk (later known as Bigfoot) seeking refuge at the Pine Ridge Agency. They were escorted to Wounded Knee Creek, where they camped for the night. The following morning, December 29, the American cavalrymen entered the camp to disarm Spotted Elk’s band. Tensions flared, a shot was fired, and a skirmish became a massacre. The Americans fired their heavy weaponry indiscriminately into the camp. Two dozen cavalrymen had been killed by the Lakotas’ concealed weapons or by friendly fire, but when the guns went silent, between 150 and 300 Native men, women, and children were dead.26

Burial of the dead after the massacre of Wounded Knee. U.S. Soldiers putting Native Americans in common grave; some corpses are frozen in different positions. South Dakota. 1891. Library of Congress.

Wounded Knee marked the end of sustained, armed Native American resistance on the Plains. Individuals continued to resist the pressures of assimilation and preserve traditional cultural practices, but sustained military defeats, the loss of sovereignty over land and resources, and the onset of crippling poverty on the reservations marked the final decades of the nineteenth century as a particularly dark era for America’s western tribes. But for Americans, it became mythical.

VII. Rodeos, Wild West Shows, and the Mythic American West

“The American West” conjures visions of tipis, cabins, cowboys, Native Americans, farm wives in sunbonnets, and outlaws with six-shooters. Such images pervade American culture, but they are as old as the West itself: novels, rodeos, and Wild West shows mythologized the American West throughout the post–Civil War era.

American frontierswoman and professional scout Martha Jane Canary was better known to America as Calamity Jane. A figure in western folklore during her life and after, Calamity Jane was a central character in many of the increasingly popular novels and films that romanticized western life in the twentieth century. “[Martha Canary, 1852-1903, (“Calamity Jane”), full-length portrait, seated with rifle as General Crook’s scout],” c. 1895. Library of Congress.

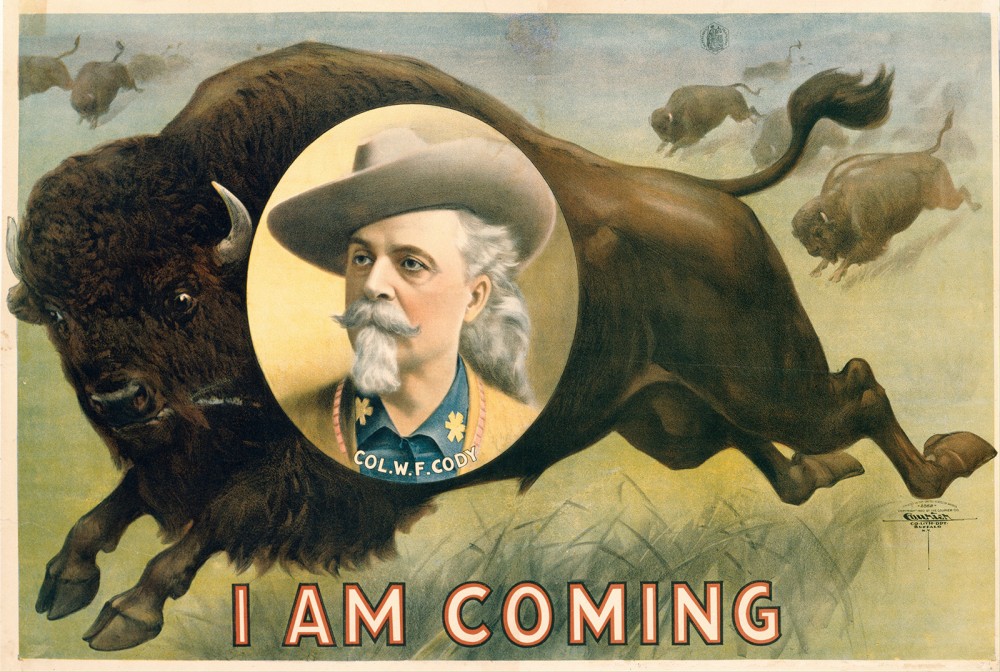

In the 1860s, Americans devoured dime novels that embellished the lives of real-life individuals such as Calamity Jane and Billy the Kid. Owen Wister’s novels, especially The Virginian, established the character of the cowboy as a gritty stoic with a rough exterior but the courage and heroism needed to rescue people from train robbers, Native Americans, and cattle rustlers. Such images were later reinforced when the emergence of rodeo added to popular conceptions of the American West. Rodeos began as small roping and riding contests among cowboys in towns near ranches or at camps at the end of the cattle trails. In Pecos, Texas, on July 4, 1883, cowboys from two ranches, the Hash Knife and the W Ranch, competed in roping and riding contests as a way to settle an argument; this event is recognized by historians of the West as the first real rodeo. Casual contests evolved into planned celebrations. Many were scheduled around national holidays, such as Independence Day, or during traditional roundup times in the spring and fall. Early rodeos took place in open grassy areas—not arenas—and included calf and steer roping and roughstock events such as bronc riding. They gained popularity and soon dedicated rodeo circuits developed. Although about 90 percent of rodeo contestants were men, women helped popularize the rodeo and several popular female bronc riders, such as Bertha Kaepernick, entered men’s events, until around 1916 when women’s competitive participation was curtailed. Americans also experienced the “Wild West”—the mythical West imagined in so many dime novels—by attending traveling Wild West shows, arguably the unofficial national entertainment of the United States from the 1880s to the 1910s. Wildly popular across the country, the shows traveled throughout the eastern United States and even across Europe and showcased what was already a mythic frontier life. William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody was the first to recognize the broad national appeal of the stock “characters” of the American West—cowboys, “Indians,” sharpshooters, cavalrymen, and rangers—and put them all together into a single massive traveling extravaganza. Operating out of Omaha, Nebraska, Buffalo Bill launched his touring show in 1883. Cody himself shunned the word show, fearing that it implied an exaggeration or misrepresentation of the West. He instead called his production “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.” He employed real cowboys and Native Americans in his productions. But it was still, of course, a show. It was entertainment, little different in its broad outlines from contemporary theater. Storylines depicted westward migration, life on the Plains, and Indigenous attacks, all punctuated by “cowboy fun”: bucking broncos, roping cattle, and sharpshooting contests.27

William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody helped commercialize the cowboy lifestyle, building a mythology around life in the Old West that produced big bucks for men like Cody. Courier Lithography Company, “’Buffalo Bill’ Cody,” 1900. Wikimedia.

Buffalo Bill, joined by shrewd business partners skilled in marketing, turned his shows into a sensation. But he was not alone. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie, another popular Wild West showman, got his start in 1886 when Cody employed him as an interpreter for Pawnee members of the show. Lillie went on to create his own production in 1888, “Pawnee Bill’s Historic Wild West.” He was Cody’s only real competitor in the business until 1908, when the two men combined their shows to create a new extravaganza, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East” (most people called it the “Two Bills Show”). It was an unparalleled spectacle. The cast included American cowboys, Mexican vaqueros, Native Americans, Russian Cossacks, Japanese acrobats, and an Australian aboriginal.

Cody and Lillie knew that Native Americans fascinated audiences in the United States and Europe, and both featured them prominently in their Wild West shows. Most Americans believed that Native cultures were disappearing or had already, and felt a sense of urgency to see their dances, hear their song, and be captivated by their bareback riding skills and their elaborate buckskin and feather attire. The shows certainly veiled the true cultural and historic value of so many Native demonstrations, and the Native performers were curiosities to white Americans, but the shows were one of the few ways for many Native Americans to make a living in the late nineteenth century.

In an attempt to appeal to women, Cody recruited Annie Oakley, a female sharpshooter who thrilled onlookers with her many stunts. Billed as “Little Sure Shot,” she shot apples off her poodle’s head and the ash from her husband’s cigar, clenched trustingly between his teeth. Gordon Lillie’s wife, May Manning Lillie, also became a skilled shot and performed as “World’s Greatest Lady Horseback Shot.” Female sharpshooters were Wild West show staples. As many as eighty toured the country at the shows’ peak. But if such acts challenged expected Victorian gender roles, female performers were typically careful to blunt criticism by maintaining their feminine identity—for example, by riding sidesaddle and wearing full skirts and corsets—during their acts.

The western “cowboys and Indians” mystique, perpetuated in novels, rodeos, and Wild West shows, was rooted in romantic nostalgia and, perhaps, in the anxieties that many felt in the late nineteenth century’s new seemingly “soft” industrial world of factory and office work. The mythical cowboy’s “aggressive masculinity” was the seemingly perfect antidote for middle- and upper-class, city-dwelling Americans who feared they “had become over-civilized” and longed for what Theodore Roosevelt called the “strenuous life.” Roosevelt himself, a scion of a wealthy New York family and later a popular American president, turned a brief tenure as a failed Dakota ranch owner into a potent part of his political image. Americans looked longingly to the West, whose romance would continue to pull at generations of Americans.

VIII. The West as History: the Turner Thesis

American anthropologist and ethnographer Frances Densmore records the Blackfoot chief Mountain Chief in 1916 for the Bureau of American Ethnology. Library of Congress.

In 1893, the American Historical Association met during that year’s World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The young Wisconsin historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his “frontier thesis,” one of the most influential theories of American history, in his essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.”

Turner looked back at the historical changes in the West and saw, instead of a tsunami of war and plunder and industry, waves of “civilization” that washed across the continent. A frontier line “between savagery and civilization” had moved west from the earliest English settlements in Massachusetts and Virginia across the Appalachians to the Mississippi and finally across the Plains to California and Oregon. Turner invited his audience to “stand at Cumberland Gap [the famous pass through the Appalachian Mountains], and watch the procession of civilization, marching single file—the buffalo following the trail to the salt springs, the Native American, the fur trader and hunter, the cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer—and the frontier has passed by.”28

Americans, Turner said, had been forced by necessity to build a rough-hewn civilization out of the frontier, giving the nation its exceptional hustle and its democratic spirit and distinguishing North America from the stale monarchies of Europe. Moreover, the style of history Turner called for was democratic as well, arguing that the work of ordinary people (in this case, pioneers) deserved the same study as that of great statesmen. Such was a novel approach in 1893.

But Turner looked ominously to the future. The Census Bureau in 1890 had declared the frontier closed. There was no longer a discernible line running north to south that, Turner said, any longer divided civilization from savagery. Turner worried for the United States’ future: what would become of the nation without the safety valve of the frontier? It was a common sentiment. Theodore Roosevelt wrote to Turner that his essay “put into shape a good deal of thought that has been floating around rather loosely.”29

The history of the West was made by many persons and peoples. Turner’s thesis was rife with faults, not only in its bald Anglo-Saxon chauvinism—in which nonwhites fell before the march of “civilization” and Chinese and Mexican immigrants were invisible—but in its utter inability to appreciate the impact of technology and government subsidies and large-scale economic enterprises alongside the work of hardy pioneers. Still, Turner’s thesis held an almost canonical position among historians for much of the twentieth century and, more importantly, captured Americans’ enduring romanticization of the West and the simplification of a long and complicated story into a march of progress.

Notes

- Based on U.S. Census figures from 1900. See, for instance, Donald Lee Parman, Indians and the American West in the Twentieth Century (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), ix.

- Rodman W. Paul, The Mining Frontiers of the West, 1848–1880 (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1963); Richard Lingenfelter, The Hard Rock Miners (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979).

- Richard White, It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own: A New History of the American West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), 216–220.

- Matthew Bowman, The Mormon People: The Making of an American Faith (New York: Random House, 2012).

- White, It’s Your Misfortune, 142–148; Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (New York: Norton, 1987), 161–162.

- White, It’s Your Misfortune; Limerick, Legacy of Conquest.

- John D. Hicks, The Populist Revolt: A History of the Farmers’ Alliance and the People’s Party (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1931), 6.

- Robert Utley, The Indian Frontier 1846–1890 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984), 76.

- Jeffrey Ostler, The Plains Sioux and U.S. Colonialism from Lewis and Clark to Wounded Knee (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

- Elliott West, The Contested Plains: Indians, Goldseekers, and the Rush to Colorado (Lawrence: Kansas University Press, 1998.

- Francis Paul Prucha, The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 482.

- Bureau of Indian Affairs, Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1875), 221.

- For the Comanche, see especially Pekka Hämäläinen, The Comanche Empire (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008).

- Ostler, The Plains Sioux and U.S. Colonialism.

- Utley, The Indian Frontier.

- Boyd Cothran, Remembering the Modoc War: Redemptive Violence and the Making of American Innocence (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

- Report of the Secretary of War, Being Part of the Message and Documents Communicated to the Two Houses of Congress, Beginning of the Second Session of the Forty-Fifth Congress. Volume I (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office 1877), 630.

- Alfred D. Chandler Jr. The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1977).

- Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (New York: Norton, 2011), 107.

- Walter Licht, Working on the Railroad: The Organization of Work in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), chap. 5.

- John F. Stover, The Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads (New York: Routledge, 1999), 15, 17, 39, 49.

- Richard W. Slatta, Cowboys of the Americas (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994).

- Limerick, Legacy of Conquest, 195–199; White, It’s Your Misfortune, 115.

- On the Ghost Dance Religion, see especially Louis S. Warren, God’s Red Son: The Ghost Dance Religion and the Making of Modern America (New York: Basic, 2017).

- See, for instance, Oliver Knight, Following the Indian Wars (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960).

- Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970).

- Joy S. Kasson, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: Celebrity, Memory, and Popular History (New York: Macmillan, 2001).

- Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (New York: Holt, 1921), 12.

- Kasson, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, 117.