“Women competing in low hurdle race, Washington, D.C.,” ca. 1920s. Library of Congress (LC-USZ62-65429)

I. Introduction

On a sunny day in early March 1921, Warren G. Harding took the oath to become the twenty-ninth president of the United States. He had won a landslide election by promising a “return to normalcy.” “Our supreme task is the resumption of our onward, normal way,” he declared in his inaugural address. Two months later, he said, “America’s present need is not heroics, but healing; not nostrums, but normalcy; not revolution, but restoration.” The nation still reeled from the shock of World War I, the explosion of racial violence and political repression in 1919, and, a lingering “Red Scare” sparked by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia.

More than 115,000 American soldiers had lost their lives in barely a year of fighting in Europe. Then, between 1918 and 1920, nearly seven hundred thousand Americans died in a flu epidemic that hit nearly 20 percent of the American population. Waves of labor strikes, meanwhile, hit soon after the war. Radicals bellowed. Anarchists and others sent more than thirty bombs through the mail on May 1, 1919. After wartime controls fell, the economy tanked and national unemployment hit 20 percent. Farmers’ bankruptcy rates, already egregious, now skyrocketed. Harding could hardly deliver the peace that he promised, but his message nevertheless resonated among a populace wracked by instability.

The 1920s, of course, would be anything but “normal.” The decade so reshaped American life that it came to be called by many names: the New Era, the Jazz Age, the Age of the Flapper, the Prosperity Decade, and, most commonly, the Roaring Twenties. The mass production and consumption of automobiles, household appliances, film, and radio fueled a new economy and new standards of living. New mass entertainment introduced talking films and jazz while sexual and social restraints loosened. But at the same time, many Americans turned their back on political and economic reform, denounced America’s shifting demographics, stifled immigration, retreated toward “old-time religion,” and revived the Ku Klux Klan with millions of new members. On the other hand, many Americans fought harder than ever for equal rights and cultural observers noted the appearance of “the New Woman” and “the New Negro.” Old immigrant communities that had predated new immigration quotas, meanwhile, clung to their cultures and their native faiths. The 1920s were a decade of conflict and tension. But whatever it was, it was not “normalcy.”

II. Republican White House, 1921-1933

To deliver on his promises of stability and prosperity, Harding signed legislation to restore a high protective tariff and dismantled the last wartime controls over industry. Meanwhile, the vestiges of America’s involvement in World War I and its propaganda and suspicions of anything less than “100 percent American” pushed Congress to address fears of immigration and foreign populations. A sour postwar economy led elites to raise the specter of the Russian Revolution and sideline not just the various American socialist and anarchist organizations but nearly all union activism. During the 1920s, the labor movement suffered a sharp decline in memberships. Workers lost not only bargaining power but also the support of courts, politicians, and, in large measure, the American public.1

Harding’s presidency would go down in history as among the most corrupt. Many of Harding’s cabinet appointees, however, were individuals of true stature that answered to various American constituencies. For instance, Henry C. Wallace, the vocal editor of Wallace’s Farmer and a well-known proponent of scientific farming, was made secretary of agriculture. Herbert Hoover, the popular head and administrator of the wartime Food Administration and a self-made millionaire, was made secretary of commerce. To satisfy business interests, the conservative businessman Andrew Mellon became secretary of the treasury. Mostly, however, it was the appointing of friends and close supporters, dubbed “the Ohio gang,” that led to trouble.2

Harding’s administration suffered a tremendous setback when several officials conspired to lease government land in Wyoming to oil companies in exchange for cash. Known as the Teapot Dome scandal (named after the nearby rock formation that resembled a teapot), interior secretary Albert Fall and navy secretary Edwin Denby resigned and Fall was convicted and sent to jail. Harding took vacation in the summer of 1923 so that he could think deeply on how to deal “with my God-damned friends”—it was his friends, and not his enemies, that kept him up walking the halls at nights. But then, in August 1923, Harding died suddenly of a heart attack and Vice President Calvin Coolidge ascended to the highest office in the land.3

The son of a shopkeeper, Coolidge climbed the Republican ranks from city councilman to governor of Massachusetts. As president, Coolidge sought to remove the stain of scandal but otherwise continued Harding’s economic approach, refusing to take actions in defense of workers or consumers against American business. “The chief business of the American people,” the new president stated, “is business.” One observer called Coolidge’s policy “active inactivity,” but Coolidge was not afraid of supporting business interests and wealthy Americans by lowering taxes or maintaining high tariff rates. Congress, for instance, had already begun to reduce taxes on the wealthy from wartime levels of 66 percent to 20 percent, which Coolidge championed.4

While Coolidge supported business, other Americans continued their activism. The 1920s, for instance, represented a time of great activism among American women, who had won the vote with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. Female voters, like their male counterparts, pursued many interests. Concerned about squalor, poverty, and domestic violence, women had already lent their efforts to prohibition, which went into effect under the Eighteenth Amendment in January 1920. After that point, alcohol could no longer be manufactured or sold. Other reformers urged government action to ameliorate high mortality rates among infants and children, provide federal aid for education, and ensure peace and disarmament. Some activists advocated protective legislation for women and children, while Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party called for the elimination of all legal distinctions “on account of sex” through the proposed Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which was introduced but defeated in Congress.5

During the 1920s, the National Woman’s Party fought for the rights of women beyond that of suffrage, which they had secured through the 19th Amendment in 1920. They organized private events, like the tea party pictured here, and public campaigning, such as the introduction of the Equal Rights Amendment to Congress, as they continued the struggle for equality. Library of Congress.

National politics in the 1920s were dominated by the Republican Party, which held not only the presidency but both houses of Congress as well. Coolidge decided not to seek a second term in 1928. A man of few words, “Silent Cal” publicized his decision by handing a scrap of paper to a reporter that simply read: “I do not choose to run for president in 1928.” That year’s race became a contest between the Democratic governor of New York, Al Smith, whose Catholic faith and immigrant background aroused nativist suspicions and whose connections to Tammany Hall and anti-Prohibition politics offended reformers, and the Republican candidate, Herbert Hoover, whose all-American, Midwestern, Protestant background and managerial prowess during World War I endeared him to American voters.6 Hoover focused on economic growth and prosperity. He had served as secretary of commerce under Harding and Coolidge and claimed credit for the sustained growth seen during the 1920s. “We in America to-day are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land,” he said when he launched his 1928 presidential campaign.” Given a chance to go forward with the policies of the last eight years, and we shall soon with the help of God be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this nation.”7 Despite Hoover’s claims–which, after the onset of the Great Depression the following year, would seem farcical–much of the election centered on Smith’s religion and his opposition to Prohibition. Many Protestant ministers preached against Smith and warned that he would be enthralled to the pope. Hoover won in a landslide. While Smith won handily in the nation’s largest cities, portending future political trends, he lost most of the rest of the country. Even several solidly Democratic southern states pulled the lever for a Republican for the first time since Reconstruction.8

III. Culture of Consumption

“Change is in the very air Americans breathe, and consumer changes are the very bricks out of which we are building our new kind of civilization,” announced marketing expert and home economist Christine Frederick in her influential 1929 monograph, Selling Mrs. Consumer. The book, which was based on one of the earliest surveys of American buying habits, advised manufacturers and advertisers how to capture the purchasing power of women, who, according to Frederick, accounted for 90 percent of household expenditures. Aside from granting advertisers insight into the psychology of the “average” consumer, Frederick’s text captured the tremendous social and economic transformations that had been wrought over the course of her lifetime.9

Indeed, the America of Frederick’s birth looked very different from the one she confronted in 1929. The consumer change she studied had resulted from the industrial expansion of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. With the discovery of new energy sources and manufacturing technologies, industrial output flooded the market with a range of consumer products such as ready-to-wear clothing, convenience foods, and home appliances. By the end of the nineteenth century, output had risen so dramatically that many contemporaries feared supply had outpaced demand and that the nation would soon face the devastating financial consequences of overproduction. American businessmen attempted to avoid this catastrophe by developing new merchandising and marketing strategies that transformed distribution and stimulated a new culture of consumer desire.10

The department store stood at the center of this early consumer revolution. By the 1880s, several large dry-goods houses blossomed into modern retail department stores. These emporiums concentrated a broad array of goods under a single roof, allowing customers to purchase shirtwaists and gloves alongside toy trains and washbasins. To attract customers, department stores relied on more than variety. They also employed innovations in service (such as access to restaurants, writing rooms, and babysitting) and spectacle (such as elaborately decorated store windows, fashion shows, and interior merchandise displays). Marshall Field & Co. was among the most successful of these ventures. Located on State Street in Chicago, the company pioneered many of these strategies, including establishing a tearoom that provided refreshment to the well-heeled female shoppers who composed the store’s clientele. Reflecting on the success of Field’s marketing techniques, Thomas W. Goodspeed, an early trustee of the University of Chicago, wrote, “Perhaps the most notable of Mr. Field’s innovations was that he made a store in which it was a joy to buy.”11

In the 1920s Americans across the country bought magazines like Photoplay in order to get more information about the stars of their new favorite entertainment media: the movies. Advertisers took advantage of this broad audience to promote a wide range of goods and services to both men and women. Archive.org.

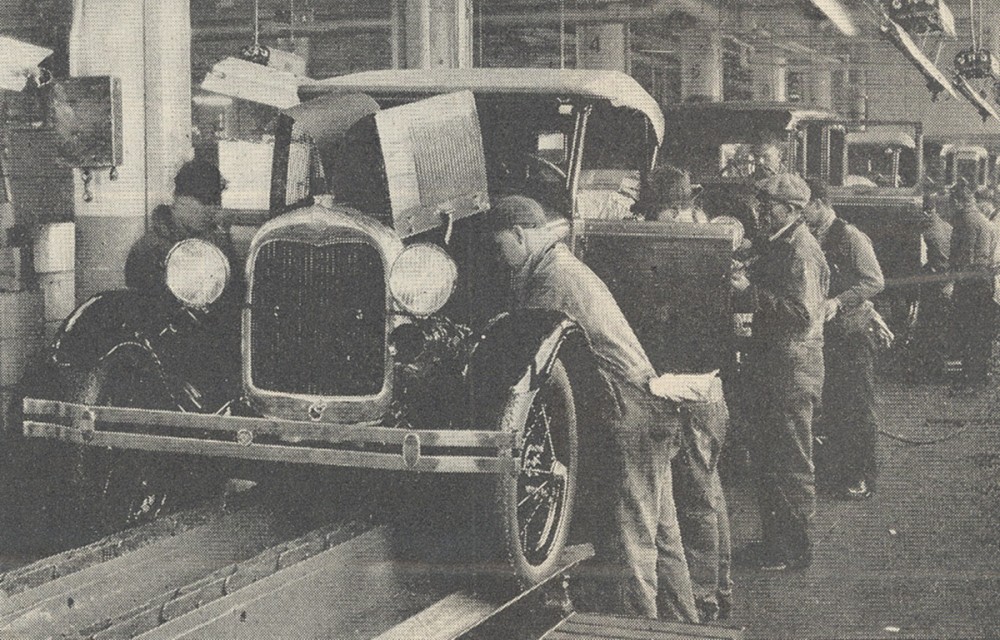

The joy of buying infected a growing number of Americans in the early twentieth century as the rise of mail-order catalogs, mass-circulation magazines, and national branding further stoked consumer desire. The automobile industry also fostered the new culture of consumption by promoting the use of credit. By 1927, more than 60 percent of American automobiles were sold on credit, and installment purchasing was made available for nearly every other large consumer purchase. Spurred by access to easy credit, consumer expenditures for household appliances, for example, grew by more than 120 percent between 1919 and 1929. Henry Ford’s assembly line, which advanced production strategies practiced within countless industries, brought automobiles within the reach of middle-income Americans and further drove the spirit of consumerism. By 1925, Ford’s factories were turning out a Model-T every ten seconds. The number of registered cars ballooned from just over nine million in 1920 to nearly twenty-seven million by the decade’s end. Americans owned more cars than Great Britain, Germany, France, and Italy combined. In the late 1920s, 80 percent of the world’s cars drove on American roads.

IV. Culture of Escape

As transformative as steam and iron had been in the previous century, gasoline and electricity—embodied most dramatically for many Americans in automobiles, film, and radio—propelled not only consumption but also the famed popular culture in the 1920s. “We wish to escape,” wrote Edgar Burroughs, author of the Tarzan series, “. . . the restrictions of manmade laws, and the inhibitions that society has placed upon us.” Burroughs authored a new Tarzan story nearly every year from 1914 until 1939. “We would each like to be Tarzan,” he said. “At least I would; I admit it.” Like many Americans in the 1920s, Burroughs sought to challenge and escape the constraints of a society that seemed more industrialized with each passing day.12

Just like Burroughs, Americans escaped with great speed. Whether through the automobile, Hollywood’s latest films, jazz records produced on Tin Pan Alley, or the hours spent listening to radio broadcasts of Jack Dempsey’s prizefights, the public wrapped itself in popular culture. One observer estimated that Americans belted out the silly musical hit “Yes, We Have No Bananas” more than “The Star Spangled Banner” and all the hymns in all the hymnals combined.13

As the automobile became more popular and more reliable, more people traveled more frequently and attempted greater distances. Women increasingly drove themselves to their own activities as well as those of their children. Vacationing Americans sped to Florida to escape northern winters. Young men and women fled the supervision of courtship, exchanging the staid parlor couch for sexual exploration in the backseat of a sedan. In order to serve and capture the growing number of drivers, Americans erected gas stations, diners, motels, and billboards along the roadside. Automobiles themselves became objects of entertainment: nearly one hundred thousand people gathered to watch drivers compete for the $50,000 prize of the Indianapolis 500.

Side view of a Ford sedan with four passengers and a woman getting in on the driver’s side, ca.1923. Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-54096.

Meanwhile, the United States dominated the global film industry. By 1930, as moviemaking became more expensive, a handful of film companies took control of the industry. Immigrants, mostly of Jewish heritage from central and Eastern Europe, originally “invented Hollywood” because most turn-of-the-century middle- and upper-class Americans viewed cinema as lower-class entertainment. After their parents emigrated from Poland in 1876, Harry, Albert, Sam, and Jack Warner (who were, according to family lore, given the name when an Ellis Island official could not understand their surname) founded Warner Bros. In 1918, Universal, Paramount, Columbia, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) were all founded by or led by Jewish executives. Aware of their social status as outsiders, these immigrants (or sons of immigrants) purposefully produced films that portrayed American values of opportunity, democracy, and freedom.

Not content with distributing thirty-minute films in nickelodeons, film moguls produced longer, higher-quality films and showed them in palatial theaters that attracted those who had previously shunned the film industry. But as filmmakers captured the middle and upper classes, they maintained working-class moviegoers by blending traditional and modern values. Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 epic The Ten Commandments depicted orgiastic revelry, for instance, while still managing to celebrate a biblical story. But what good was a silver screen in a dingy theater? Moguls and entrepreneurs soon constructed picture palaces. Samuel Rothafel’s Roxy Theater in New York held more than six thousand patrons who could be escorted by a uniformed usher past gardens and statues to their cushioned seat. In order to show The Jazz Singer (1927), the first movie with synchronized words and pictures, the Warners spent half a million to equip two theaters. “Sound is a passing fancy,” one MGM producer told his wife, but Warner Bros.’ assets, which increased from just $5,000,000 in 1925 to $230,000,000 in 1930, tell a different story.14

Americans fell in love with the movies. Whether it was the surroundings, the sound, or the production budgets, weekly movie attendance skyrocketed from sixteen million in 1912 to forty million in the early 1920s. Hungarian immigrant William Fox, founder of Fox Film Corporation, declared that “the motion picture is a distinctly American institution” because “the rich rub elbows with the poor” in movie theaters. With no seating restriction, the one-price admission was accessible for nearly all Americans (African Americans, however, were either excluded or segregated). Women represented more than 60 percent of moviegoers, packing theaters to see Mary Pickford, nicknamed “America’s Sweetheart,” who was earning one million dollars a year by 1920 through a combination of film and endorsements contracts. Pickford and other female stars popularized the “flapper,” a woman who favored short skirts, makeup, and cigarettes.

Mary Pickford’s film personas led the glamorous and lavish lifestyle that female movie-goers of the 1920s desired so much. Mary Pickford, 1920. Library of Congress.

As Americans went to the movies more and more, at home they had the radio. Italian scientist Guglielmo Marconi transmitted the first transatlantic wireless (radio) message in 1901, but radios in the home did not become available until around 1920, when they boomed across the country. Around half of American homes contained a radio by 1930. Radio stations brought entertainment directly into the living room through the sale of advertisements and sponsorships, from The Maxwell House Hour to the Lucky Strike Orchestra. Soap companies sponsored daytime dramas so frequently that an entire genre—“soap operas”—was born, providing housewives with audio adventures that stood in stark contrast to common chores. Though radio stations were often under the control of corporations like the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) or the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), radio programs were less constrained by traditional boundaries in order to capture as wide an audience as possible, spreading popular culture on a national level.

Radio exposed Americans to a broad array of music. Jazz, a uniquely American musical style popularized by the African-American community in New Orleans, spread primarily through radio stations and records. The New York Times had ridiculed jazz as “savage” because of its racial heritage, but the music represented cultural independence to others. As Harlem-based musician William Dixon put it, “It did seem, to a little boy, that . . . white people really owned everything. But that wasn’t entirely true. They didn’t own the music that I played.” The fast-paced and spontaneity-laced tunes invited the listener to dance along. “When a good orchestra plays a ‘rag,’” dance instructor Vernon Castle recalled, “one has simply got to move.” Jazz became a national sensation, played and heard by both white and Black Americans. Jewish Lithuanian-born singer Al Jolson—whose biography inspired The Jazz Singer and who played the film’s titular character—became the most popular singer in America.15

The 1920s also witnessed the maturation of professional sports. Play-by-play radio broadcasts of major collegiate and professional sporting events marked a new era for sports, despite the institutionalization of racial segregation in most. Suddenly, Jack Dempsey’s left crosses and right uppercuts could almost be felt in homes across the United States. Dempsey, who held the heavyweight championship for most of the decade, drew million-dollar gates and inaugurated “Dempseymania” in newspapers across the country. Red Grange, who carried the football with a similar recklessness, helped popularize professional football, which was then in the shadow of the college game. Grange left the University of Illinois before graduating to join the Chicago Bears in 1925. “There had never been such evidence of public interest since our professional league began,” recalled Bears owner George Halas of Grange’s arrival.16

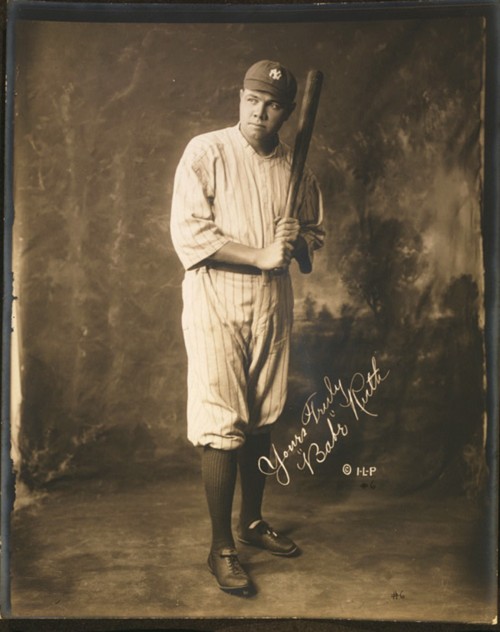

Perhaps no sports figure left a bigger mark than did Babe Ruth. Born George Herman Ruth, the “Sultan of Swat” grew up in an orphanage in Baltimore’s slums. Ruth’s emergence onto the national scene was much needed, as the baseball world had been rocked by the so-called Black Sox Scandal in which eight players allegedly agreed to throw the 1919 World Series. Ruth hit fifty-four home runs in 1920, which was more than any other team combined. Baseball writers called Ruth a superman, and more Americans could recognize Ruth than they could then-president Warren G. Harding.

After an era of destruction and doubt brought about by World War I, Americans craved heroes who seemed to defy convention and break boundaries. Dempsey, Grange, and Ruth dominated their respective sports, but only Charles Lindbergh conquered the sky. On May 21, 1927, Lindbergh concluded the first ever nonstop solo flight from New York to Paris. Armed with only a few sandwiches, some bottles of water, paper maps, and a flashlight, Lindbergh successfully navigated over the Atlantic Ocean in thirty-three hours. Some historians have dubbed Lindbergh the “hero of the decade,” not only for his transatlantic journey but because he helped to restore the faith of many Americans in individual effort and technological advancement. In a world so recently devastated by machine guns, submarines, and chemical weapons, Lindbergh’s flight demonstrated that technology could inspire and accomplish great things. Outlook Magazine called Lindbergh “the heir of all that we like to think is best in America.”17

The decade’s popular culture seemed to revolve around escape. Coney Island in New York marked new amusements for young and old. Americans drove their sedans to massive theaters to enjoy major motion pictures. Radio towers broadcasted the bold new sound of jazz, the adventures of soap operas, and the feats of amazing athletes. Dempsey and Grange seemed bigger, stronger, and faster than any who dared to challenge them. Babe Ruth smashed home runs out of ball parks across the country. And Lindbergh escaped the earth’s gravity and crossed an entire ocean. Neither Dempsey nor Ruth nor Lindbergh made Americans forget the horrors of World War I and the chaos that followed, but they made it seem as if the future would be that much brighter.

Babe Ruth’s incredible talent accelerated the popularity of baseball, cementing it as America’s pastime. Ruth’s propensity to shatter records made him a national hero. Library of Congress.

V. “The New Woman”

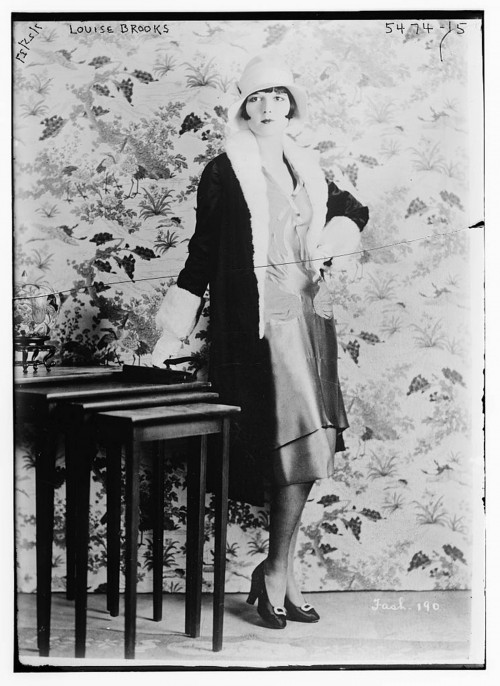

This “new breed” of women – known as the flapper – went against the gender proscriptions of the era, bobbing their hair, wearing short dresses, listening to jazz, and flouting social and sexual norms. While liberating in many ways, these behaviors also reinforced stereotypes of female carelessness and obsessive consumerism that would continue throughout the twentieth century. Library of Congress.

The rising emphasis on spending and accumulation nurtured a national ethos of materialism and individual pleasure. These impulses were embodied in the figure of the flapper, whose bobbed hair, short skirts, makeup, cigarettes, and carefree spirit captured the attention of American novelists such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sinclair Lewis. Rejecting the old Victorian values of desexualized modesty and self-restraint, young “flappers” seized opportunities for the public coed pleasures offered by new commercial leisure institutions, such as dance halls, cabarets, and nickelodeons, not to mention the illicit blind tigers and speakeasies spawned by Prohibition. So doing, young American women had helped usher in a new morality that permitted women greater independence, freedom of movement, and access to the delights of urban living. In the words of psychologist G. Stanley Hall, “She was out to see the world and, incidentally, be seen of it.”

Such sentiments were repeated in an oft-cited advertisement in a 1930 edition of the Chicago Tribune: “Today’s woman gets what she wants. The vote. Slim sheaths of silk to replace voluminous petticoats. Glassware in sapphire blue or glowing amber. The right to a career. Soap to match her bathroom’s color scheme.” As with so much else in the 1920s, however, sex and gender were in many ways a study in contradictions. It was the decade of the “New Woman,” and one in which only 10 percent of married women—although nearly half of unmarried women—worked outside the home.18 It was a decade in which new technologies decreased time requirements for household chores, and one in which standards of cleanliness and order in the home rose to often impossible standards. It was a decade in which women finally could exercise their right to vote, and one in which the often thinly bound women’s coalitions that had won that victory splintered into various causes. Finally, it was a decade in which images such as the “flapper” gave women new modes of representing femininity, and one in which such representations were often inaccessible to women of certain races, ages, and socioeconomic classes.

Women undoubtedly gained much in the 1920s. There was a profound and keenly felt cultural shift that, for many women, meant increased opportunity to work outside the home. The number of professional women, for example, significantly rose in the decade. But limits still existed, even for professional women. Occupations such as law and medicine remained overwhelmingly male: most female professionals were in feminized professions such as teaching and nursing. And even within these fields, it was difficult for women to rise to leadership positions.

Further, it is crucial not to overgeneralize the experience of all women based on the experiences of a much-commented-upon subset of the population. A woman’s race, class, ethnicity, and marital status all had an impact on both the likelihood that she worked outside the home and the types of opportunities that were available to her. While there were exceptions, for many minority women, work outside the home was not a cultural statement but rather a financial necessity (or both), and physically demanding, low-paying domestic service work continued to be the most common job type. Young, working-class white women were joining the workforce more frequently, too, but often in order to help support their struggling mothers and fathers.

For young, middle-class, white women—those most likely to fit the image of the carefree flapper—the most common workplace was the office. These predominantly single women increasingly became clerks, jobs that had been primarily male earlier in the century. But here, too, there was a clear ceiling. While entry-level clerk jobs became increasingly feminized, jobs at a higher, more lucrative level remained dominated by men. Further, rather than changing the culture of the workplace, the entrance of women into lower-level jobs primarily changed the coding of the jobs themselves. Such positions simply became “women’s work.”

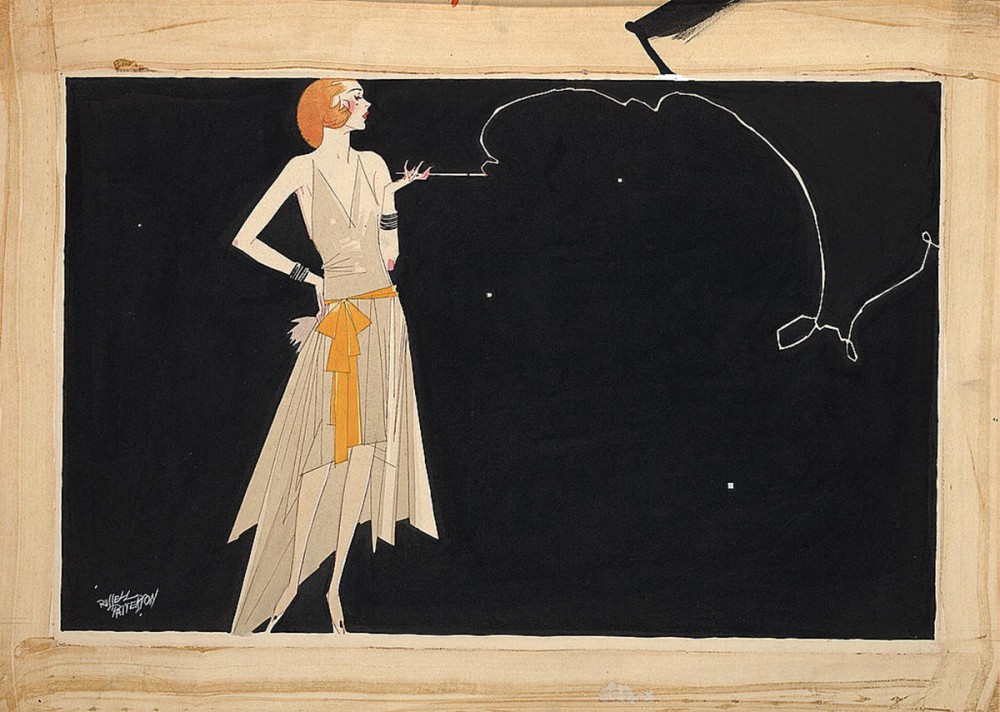

The frivolity, decadence, and obliviousness of the 1920s was embodied in the image of the flapper, the stereotyped carefree and indulgent woman of the Roaring Twenties depicted by Russell Patterson’s drawing. Library of Congress.

Finally, as these same women grew older and married, social changes became even subtler. Married women were, for the most part, expected to remain in the domestic sphere. And while new patterns of consumption gave them more power and, arguably, more autonomy, new household technologies and philosophies of marriage and child-rearing increased expectations, further tying these women to the home—a paradox that becomes clear in advertisements such as the one in the Chicago Tribune. Of course, the number of women in the workplace cannot exclusively measure changes in sex and gender norms. Attitudes towards sex, for example, continued to change in the 1920s as well, a process that had begun decades before. This, too, had significantly different impacts on different social groups. But for many women—particularly young, college-educated white women—an attempt to rebel against what they saw as a repressive Victorian notion of sexuality led to an increase in premarital sexual activity strong enough that it became, in the words of one historian, “almost a matter of conformity.”19

Meanwhile, especially in urban centers such as New York, the gay community flourished. While gay males had to contend with the increased policing of their daily lives, especially later in the decade, they generally lived more openly in such cities than they would be able to for many decades following World War II.20 At the same time, for many lesbians in the decade, the increased sexualization of women brought new scrutiny to same-sex female relationships previously dismissed as harmless.21

Ultimately, the most enduring symbol of the changing notions of gender in the 1920s remains the flapper. And indeed, that image was a “new” available representation of womanhood in the 1920s. But it is just that: a representation of womanhood of the 1920s. There were many women in the decade of differing races, classes, ethnicities, and experiences, just as there were many men with different experiences. For some women, the 1920s were a time of reorganization, new representations, and new opportunities. For others, it was a decade of confusion, contradiction, new pressures, and struggles new and old.

VI. “The New Negro”

The iniquities of Jim Crow segregation, the barbarities of America’s lynching epidemic, and the depravities of 1919’s Red Summer weighed heavily upon Black Americans as they entered the 1920s. The injustices and the violence continued. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, Black Americans had built up the Greenwood District with commerce and prosperity. Booker T. Washington called it the “Black Wall Street.” On the evening of May 31, 1921, spurred by a false claim of sexual assault levied against a young Black man–nineteen-year-old Dick Rowland had likely either tripped over a young white elevator operator’s foot or tripped and brushed the woman’s shoulder with his hand–a white mob mobilized, armed themselves, and destroyed the prosperous neighborhood. Over thirty square blocks were destroyed. Mobs burned over 1,000 homes and killed as many as several hundred Black Tulsans. Survivors recalled the mob using heavy machine guns, and others reported planes circling overhead, firing rifles and dropping firebombs. When order was finally restored the next day, the bodies of the victims were buried in mass graves. Thousands of survivors were left homeless.

The relentlessness of racial violence awoke a new generation of Black Americans to new alternatives. The Great Migration had pulled enormous numbers of Black southerners northward, and, just as cultural limits loosened across the nation, the 1920s represented a period of self-reflection among African Americans, especially those in northern cities. New York City was a popular destination of Black Americans during the Great Migration. The city’s Black population grew 257 percent, from 91,709 in 1910 to 327,706 by 1930 (the white population grew only 20 percent).22 Moreover, by 1930, some 98,620 foreign-born Black people had migrated to the United States. Nearly half made their home in Manhattan’s Harlem district.23

Harlem originally lay between Fifth Avenue and Eighth Avenue and 130th Street to 145th Street. By 1930, the district had expanded to 155th Street and was home to 164,000 people, mostly African Americans. Continuous relocation to “the greatest Negro City in the world” exacerbated problems with crime, health, housing, and unemployment.24 Nevertheless, it brought together a mass of Black people energized by race pride, military service in World War I, the urban environment, and, for many, ideas of Pan-Africanism or Garveyism (discussed shortly). James Weldon Johnson called Harlem “the Culture Capital.”25 The area’s cultural ferment produced the Harlem Renaissance and fostered what was then termed the New Negro Movement.

Alain Locke did not coin the term New Negro, but he did much to popularize it. In the 1925 book The New Negro, Locke proclaimed that the generation of subservience was no more—“we are achieving something like a spiritual emancipation.” Bringing together writings by men and women, young and old, Black and white, Locke produced an anthology that was of African Americans, rather than only about them. The book joined many others. Popular Harlem Renaissance writers published some twenty-six novels, ten volumes of poetry, and countless short stories between 1922 and 1935.26 Alongside the well-known Langston Hughes and Claude McKay, female writers like Jessie Redmon Fauset and Zora Neale Hurston published nearly one third of these novels. While themes varied, the literature frequently explored and countered pervading stereotypes and forms of American racial prejudice.

The Harlem Renaissance was manifested in theater, art, and music. For the first time, Broadway presented Black actors in serious roles. The 1924 production Dixie to Broadway was the first all-Black show with mainstream showings.27 In art, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Aaron Douglas, and Palmer Hayden showcased Black cultural heritage and captured the population’s current experience. In music, jazz rocketed in popularity. Eager to hear “real jazz,” whites journeyed to Harlem’s Cotton Club and Smalls. Next to Greenwich Village, Harlem’s nightclubs and speakeasies (venues where alcohol was publicly consumed) presented a place where sexual freedom and gay life thrived. Unfortunately, while headliners like Duke Ellington were hired to entertain at Harlem’s venues, the surrounding Black community was usually excluded. Furthermore, Black performers were often restricted from restroom use and relegated to service door entry. As the Renaissance faded to a close, several Harlem Renaissance artists went on to produce important works indicating that this movement was but one component in African American’s long history of cultural and intellectual achievements.28

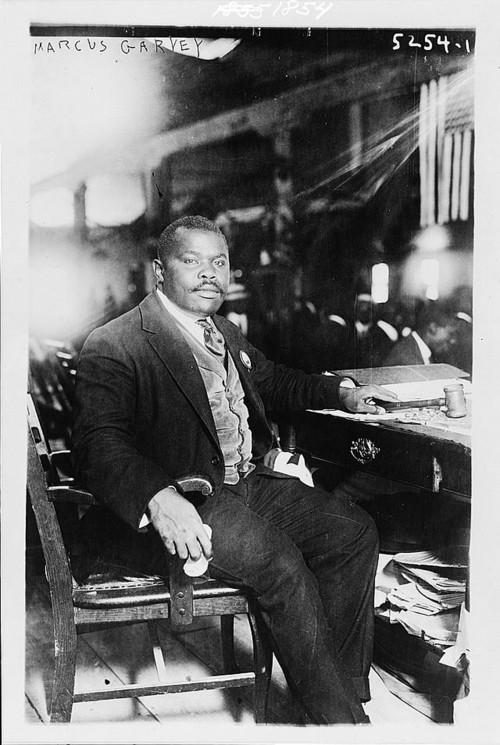

Garveyism, criticized as too radical, nevertheless formed a substantial following and was a major stimulus for later Black nationalistic movements. Photograph of Marcus Garvey, August 5, 1924. Library of Congress.

The explosion of African American self-expression found multiple outlets in politics. In the 1910s and 1920s, perhaps no one so attracted disaffected Black activists as Marcus Garvey. Garvey was a Jamaican publisher and labor organizer who arrived in New York City in 1916. Within just a few years of his arrival, he built the largest Black nationalist organization in the world, the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).29 Inspired by Pan-Africanism and Booker T. Washington’s model of industrial education, and critical of what he saw as Du Bois’s elitist strategies in service of Black elites, Garvey sought to promote racial pride, encourage Black economic independence, and root out racial oppression in Africa and the Diaspora.30

Headquartered in Harlem, the UNIA published a newspaper, Negro World, and organized elaborate parades in which members, known as Garveyites, dressed in ornate, militaristic regalia and marched down city streets. The organization criticized the slow pace of the judicial focus of the NAACP as well as its acceptance of memberships and funds from whites. “For the Negro to depend on the ballot and his industrial progress alone,” Garvey opined, “will be hopeless as it does not help him when he is lynched, burned, jim-crowed, and segregated.” In 1919, the UNIA announced plans to develop a shipping company called the Black Star Line as part of a plan that pushed for Black Americans to reject the political system and to “return to Africa” instead. Most of the investments came in the form of shares purchased by UNIA members, many of whom heard Garvey give rousing speeches across the country about the importance of establishing commercial ventures between African Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, and Africans.31

Garvey’s detractors disparaged these public displays and poorly managed business ventures, and they criticized Garvey for peddling empty gestures in place of measures that addressed the material concerns of African Americans. NAACP leaders depicted Garvey’s plan as one that simply said, “Give up! Surrender! The struggle is useless.” Enflamed by his aggressive attacks on other Black activists and his radical ideas of racial independence, many African American and Afro-Caribbean leaders worked with government officials and launched the “Garvey Must Go” campaign, which culminated in his 1922 indictment and 1925 imprisonment and subsequent deportation for “using the mails for fraudulent purposes.” The UNIA never recovered its popularity or financial support, even after Garvey’s pardon in 1927, but his movement made a lasting impact on Black consciousness in the United States and abroad. He inspired the likes of Malcolm X, whose parents were Garveyites, and Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana. Garvey’s message, perhaps best captured by his rallying cry, “Up, you mighty race,” resonated with African Americans who found in Garveyism a dignity not granted them in their everyday lives. In that sense, it was all too typical of the Harlem Renaissance.32

VII. Culture War

For all of its cultural ferment, however, the 1920s were also a difficult time for radicals and immigrants and anything “modern.” Fear of foreign radicals led to the executions of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two Italian anarchists, in 1927. In May 1920, the two had been arrested for robbery and murder connected with an incident at a Massachusetts factory. Their guilty verdicts were appealed for years as the evidence surrounding their convictions was slim. For instance, while one eyewitness claimed that Vanzetti drove the getaway car, accounts of others described a different person altogether. Nevertheless, despite worldwide lobbying by radicals and a respectable movement among middle-class Italian organizations in the United States, the two men were executed on August 23, 1927. Vanzetti conceivably provided the most succinct reason for his death, saying, “This is what I say . . . . I am suffering because I am a radical and indeed I am a radical; I have suffered because I was an Italian, and indeed I am an Italian.”33

Many Americans expressed anxieties about the changes that had remade the United States and, seeking scapegoats, many middle-class white Americans pointed to Eastern European and Latin American immigrants (Asian immigration had already been almost completely prohibited), African Americans who now pushed harder for civil rights, and, after migrating out of the American South to northern cities as a part of the Great Migration, the mass exodus that carried nearly half a million Black Southerners out of the South between 1910 and 1920. Protestants, meanwhile, continued to denounce the Roman Catholic Church and charged that American Catholics gave their allegiance to the pope and not to their country.

In 1921, Congress passed the Emergency Immigration Act as a stopgap immigration measure and then, three years later, permanently established country-of-origin quotas through the National Origins Act. The number of immigrants annually admitted to the United States from each nation was restricted to 2 percent of the population who had come from that country and resided in the United States in 1890. (By pushing back three decades, past the recent waves of “new” immigrants from southern and Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Asia, the law made it extremely difficult for immigrants outside northern Europe to legally enter the United States.) The act also explicitly excluded all Asians, although, to satisfy southern and western growers, it temporarily omitted restrictions on Mexican immigrants. The Sacco and Vanzetti trial and sweeping immigration restrictions pointed to a rampant nativism. A great number of Americans worried about a burgeoning America that did not resemble the one of times past. Many writers perceived that the country was now riven by a culture war.

VIII. Fundamentalist Christianity

In addition to alarms over immigration and the growing presence of Catholicism and Judaism, a new core of Christian fundamentalists were very much concerned about relaxed sexual mores and increased social freedoms, especially as found in city centers. Although never a centralized group, most fundamentalists lashed out against what they saw as a sagging public morality, a world in which Protestantism seemed challenged by Catholicism, women exercised ever greater sexual freedoms, public amusements encouraged selfish and empty pleasures, and critics mocked Prohibition through bootlegging and speakeasies.

Christian Fundamentalism arose most directly from a doctrinal dispute among Protestant leaders. Liberal theologians sought to intertwine religion with science and secular culture. These Modernists, influenced by the biblical scholarship of nineteenth-century German academics, argued that Christian doctrines about the miraculous might be best understood metaphorically. The Church, they said, needed to adapt itself to the world. According to the Baptist pastor Harry Emerson Fosdick, the “coming of Christ” might occur “slowly . . . but surely, [as] His will and principles [are] worked out by God’s grace in human life and institutions.”34 The social gospel, which encouraged Christians to build the Kingdom of God on earth by working against social and economic inequality, was very much tied to liberal theology.

During the 1910s, funding from oil barons Lyman and Milton Stewart enabled the evangelist A. C. Dixon to commission some ninety essays to combat religious liberalism. The collection, known as The Fundamentals, became the foundational documents of Christian fundamentalism, from which the movement’s name is drawn. Contributors agreed that Christian faith rested on literal truths, that Jesus, for instance, would physically return to earth at the end of time to redeem the righteous and damn the wicked. Some of the essays put forth that human endeavor would not build the Kingdom of God, while others covered such subjects as the virgin birth and biblical inerrancy. American fundamentalists spanned Protestant denominations and borrowed from diverse philosophies and theologies, most notably the holiness movement, the larger revivalism of the nineteenth century, and new dispensationalist theology (in which history proceeded, and would end, through “dispensations” by God). They did, however, all agree that modernism was the enemy and the Bible was the inerrant word of God. It was a fluid movement often without clear boundaries, but it featured many prominent clergymen, including the well-established and extremely vocal John Roach Straton (New York), J. Frank Norris (Texas), and William Bell Riley (Minnesota).35

On March 21, 1925, in a tiny courtroom in Dayton, Tennessee, fundamentalists gathered to tackle the issues of creation and evolution. A young biology teacher, John T. Scopes, was being tried for teaching his students evolutionary theory in violation of the Butler Act, a state law preventing evolutionary theory or any theory that denied “the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible” from being taught in publicly funded Tennessee classrooms. Seeing the act as a threat to personal liberty, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) immediately sought a volunteer for a “test” case, hoping that the conviction and subsequent appeals would lead to a day in the Supreme Court, testing the constitutionality of the law. It was then that Scopes, a part-time teacher and coach, stepped up and voluntarily admitted to teaching evolution (Scopes’s violation of the law was never in question). Thus the stage was set for the pivotal courtroom showdown—“the trial of the century”—between the champions and opponents of evolution that marked a key moment in an enduring American “culture war.”36

The case became a public spectacle. Clarence Darrow, an agnostic attorney and a keen liberal mind from Chicago, volunteered to aid the defense and came up against William Jennings Bryan. Bryan, the “Great Commoner,” was the three-time presidential candidate who in his younger days had led the political crusade against corporate greed. He had done so then with a firm belief in the righteousness of his cause, and now he defended biblical literalism in similar terms. The theory of evolution, Bryan said, with its emphasis on the survival of the fittest, “would eliminate love and carry man back to a struggle of tooth and claw.”37

During the Scopes Trial, Clarence Darrow (right) savaged the idea of a literal interpretation of the Bible. “Dudley Field Malone, Dr. John R. Neal, and Clarence Darrow in Chicago, Illinois.” The Clarence Darrow Digital Collection, University of Minnesota.

Newspapermen and spectators flooded the small town of Dayton. Across the nation, Americans tuned their radios to the national broadcasts of a trial that dealt with questions of religious liberty, academic freedom, parental rights, and the moral responsibility of education. For six days in July, the men and women of America were captivated as Bryan presented his argument on the morally corrupting influence of evolutionary theory (and pointed out that Darrow made a similar argument about the corruptive potential of education during his defense of the famed killers Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb a year before). Darrow eloquently fought for academic freedom.38

At the request of the defense, Bryan took the stand as an “expert witness” on the Bible. At his age, he was no match for Darrow’s famous skills as a trial lawyer and his answers came across as blundering and incoherent, particularly as he was not in fact a literal believer in all of the Genesis account (believing—as many anti-evolutionists did—that the meaning of the word day in the book of Genesis could be taken as allegory) and only hesitantly admitted as much, not wishing to alienate his fundamentalist followers. Additionally, Darrow posed a series of unanswerable questions: Was the “great fish” that swallowed the prophet Jonah created for that specific purpose? What precisely happened astronomically when God made the sun stand still? Bryan, of course, could cite only his faith in miracles. Tied into logical contradictions, Bryan’s testimony was a public relations disaster, although his statements were expunged from the record the next day and no further experts were allowed—Scopes’s guilt being established, the jury delivered a guilty verdict in minutes. The case was later thrown out on a technicality. But few cared about the verdict. Darrow had, in many ways, at least to his defenders, already won: the fundamentalists seemed to have taken a beating in the national limelight. Journalist and satirist H. L. Mencken characterized the “circus in Tennessee” as an embarrassment for fundamentalism, and modernists remembered the “Monkey Trial” as a smashing victory. If fundamentalists retreated from the public sphere, they did not disappear entirely. Instead, they went local, built a vibrant subculture, and emerged many decades later stronger than ever.39

IX. Rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK)

This photo by popular news photographers Underwood and Underwood shows a gathering of a reported three hundred Ku Klux Klansmen just outside Washington DC to initiate a new group of men into their order. The proximity of the photographer to his subjects for one of the Klan’s notorious night-time rituals suggests that this was yet another of the Klan’s numerous publicity stunts. Underwood and Underwood, “Klan assembles Short Distance from U.S. Capitol,” (ca. 1920’s). Library of Congress.

Suspicions of immigrants, Catholics, and modernists contributed to a string of reactionary organizations. None so captured the imaginations of the country as the reborn Ku Klux Klan (KKK), a white supremacist organization that expanded beyond its Reconstruction Era anti-Black politics to now claim to protect American values and the American way of life from Black people, feminists (and other radicals), immigrants, Catholics, Jews, atheists, bootleggers, and a host of other imagined moral enemies.

Two events in 1915 are widely credited with inspiring the rebirth of the Klan: the lynching of Leo Frank and the release of The Birth of a Nation, a popular and groundbreaking film that valorized the Reconstruction Era Klan as a protector of feminine virtue and white racial purity. Taking advantage of this sudden surge of popularity, Colonel William Joseph Simmons organized what is often called the “second” Ku Klux Klan in Georgia in late 1915. This new Klan, modeled after other fraternal organizations with elaborate rituals and a hierarchy, remained largely confined to Georgia and Alabama until 1920, when Simmons began a professional recruiting effort that resulted in individual chapters being formed across the country and membership rising to an estimated five million.40

Partly in response to the migration of Black southerners to northern cities during World War I, the KKK expanded above the Mason-Dixon Line. Membership soared in Philadelphia, Detroit, Chicago, and Portland, while Klan-endorsed mayoral candidates won in Indianapolis, Denver, and Atlanta.41 The Klan often recruited through fraternal organizations such as the Freemasons and through various Protestant churches. In many areas, local Klansmen visited churches of which they approved and bestowed a gift of money on the presiding minister, often during services. The Klan also enticed people to join through large picnics, parades, rallies, and ceremonies. The Klan established a women’s auxiliary in 1923 headquartered in Little Rock, Arkansas. The Women of the Ku Klux Klan mirrored the KKK in practice and ideology and soon had chapters in all forty-eight states, often attracting women who were already part of the Prohibition movement, the defense of which was a centerpiece of Klan activism.42

Contrary to its perception of as a primarily southern and lower-class phenomenon, the second Klan had a national reach composed largely of middle-class people. Sociologist Rory McVeigh surveyed the KKK newspaper Imperial Night-Hawk for the years 1923 and 1924, at the organization’s peak, and found the largest number of Klan-related activities to have occurred in Texas, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Illinois, and Georgia. The Klan was even present in Canada, where it was a powerful force within Saskatchewan’s Conservative Party. In many states and localities, the Klan dominated politics to such a level that one could not be elected without the support of the KKK. For example, in 1924, the Klan supported William Lee Cazort for governor of Arkansas, leading his opponent in the Democratic Party primary, Thomas Terral, to seek honorary membership through a Louisiana klavern so as not to be tagged as the anti-Klan candidate. In 1922, Texans elected Earle B. Mayfield, an avowed Klansman who ran openly as that year’s “klandidate,” to the U.S. Senate. At its peak the Klan claimed between four and five million members.43

Despite the breadth of its political activism, the Klan is today remembered largely as a violent vigilante group—and not without reason. Members of the Klan and affiliated organizations often carried out acts of lynching and “nightriding”—the physical harassment of bootleggers, union activists, civil rights workers, or any others deemed “immoral” (such as suspected adulterers) under the cover of darkness or while wearing their hoods and robes. In fact, Klan violence was extensive enough in Oklahoma that Governor John C. Walton placed the entire state under martial law in 1923. Witnesses testifying before the military court disclosed accounts of Klan violence ranging from the flogging of clandestine brewers to the disfiguring of a prominent Black Tulsan for registering African Americans to vote. In Houston, Texas, the Klan maintained an extensive system of surveillance that included tapping telephone lines and putting spies in the local post office in order to root out “undesirables.” A mob organized and led by Klan members in Aiken, South Carolina, lynched Bertha Lowman and her two brothers in 1926, but no one was ever prosecuted: the sheriff, deputies, city attorney, and state representative all belonged to the Klan.44

The Klan dwindled in the face of scandal and diminished energy over the last years of the 1920s. By 1930, the Klan only had about thirty thousand members and it was largely spent as a national force, only to appear again as a much diminished force during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Great Depression

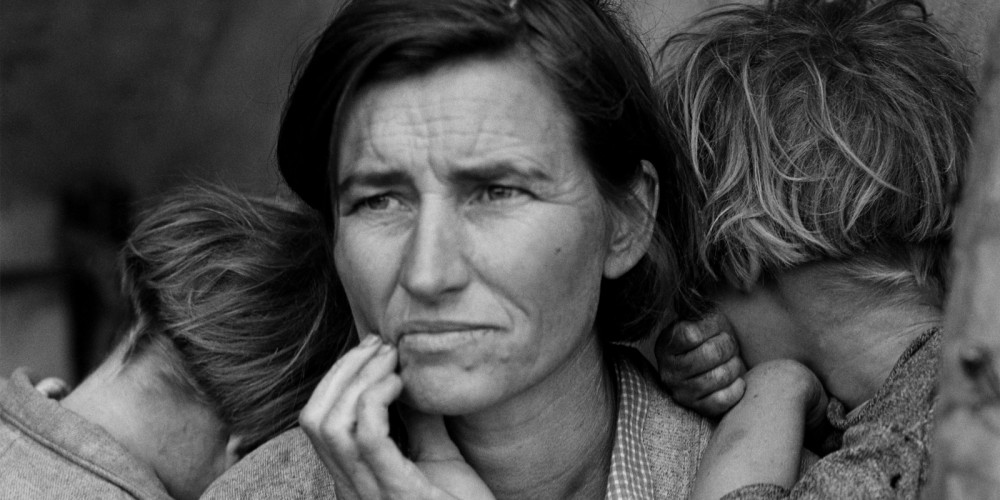

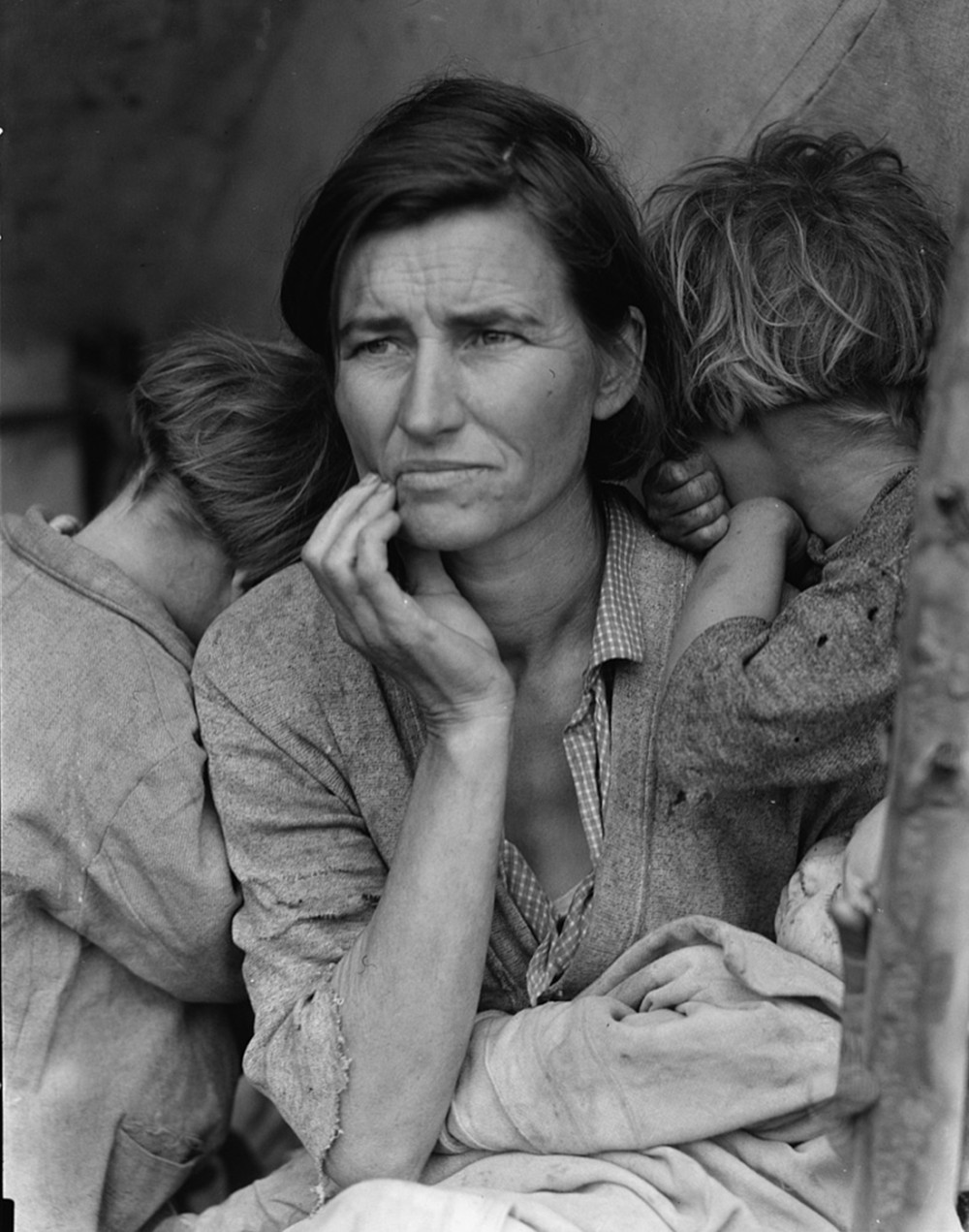

In this famous 1936 photograph by Dorothea Lange, a destitute, thirty-two-year-old mother of seven captures the agonies of the Great Depression. Library of Congress.

X. Introduction to the Great Depression

Hard times had hit the United States before, but never had an economic crisis lasted so long or inflicted as much harm as the slump that followed the 1929 crash. After nearly a decade of supposed prosperity, the economy crashed to a halt. People suddenly stopped borrowing and buying. Industries built on debt-fueled purchases sold fewer goods. Retailers lowered prices and, when that did not attract enough buyers to turn profits, they laid off workers to lower labor costs. With so many people out of work and without income, shops sold even less, dropped their prices lower still, and then shed still more workers, creating a vicious downward cycle.

Four years after the crash, the Great Depression reached its lowest point: nearly one in four Americans who wanted a job could not find one and, of those who could, more than half had to settle for part-time work. Farmers could not make enough money from their crops to make harvesting worthwhile. Food rotted in the fields of a starving nation.

The needy drew down whatever savings they had, turned to their families, and sought out charities for public assistance. Soon they all were depleted. Unemployed workers and cash-strapped farmers defaulted on their debts, including mortgages. Already over-extended banks, deprived of income, took savings accounts down with them when they closed. Fear-stricken observers went to their own banks and demanded their deposits. Banks that otherwise might have endured the crisis fell prey to panic, and shut down as well.

With so little being bought and sold, and so little lent and spent, with even bankers unable to lay their hands on money, the nation’s economy ground nearly to a halt. None of the remedies adopted by the president or the Congress succeeded—not higher tariffs, nor restriction of immigration, nor sticking to sound money, nor expressions of confidence in the resilience of the American people. Whatever good these measures achieved, it was not enough.

In the 1932 presidential election, the incumbent president, Herbert Hoover, a Republican, promised that he would stand firm against those who, he said, would destroy the U.S. Constitution to restore the economy. Chief among these supposedly dangerous experimenters was the Democratic presidential nominee, New York governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, who began his campaign by pledging a New Deal for the American people.

The voters chose Roosevelt in a landslide, inaugurating a rapid and enduring transformation in the U.S. government. Even though the New Deal never achieved as much as its proponents hoped or its opponents feared, it did more than any other peacetime program to change how Americans saw their country.

XI. The Origins of the Great Depression

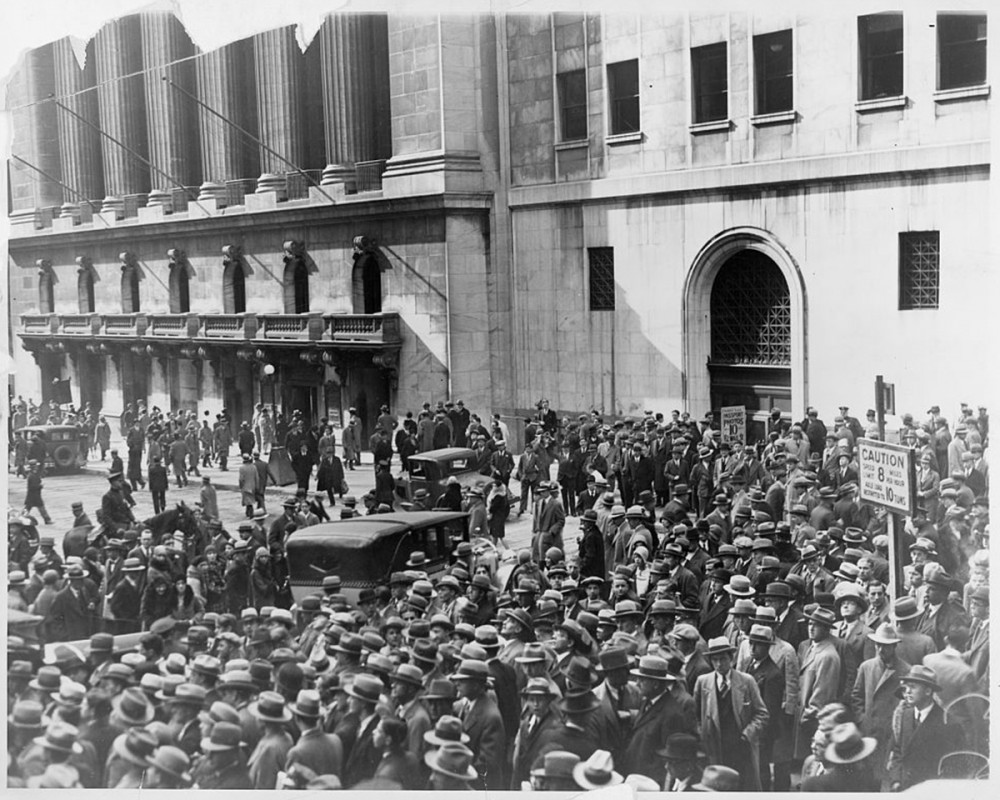

Crowds of people gather outside the New York Stock Exchange following the crash of 1929. Library of Congress.

On Thursday, October 24, 1929, stock market prices suddenly plummeted. Ten billion dollars in investments (roughly equivalent to about $100 billion today) disappeared in a matter of hours. Panicked selling set in, stock values sank to sudden lows, and stunned investors crowded the New York Stock Exchange demanding answers. Leading bankers met privately at the offices of J. P. Morgan and raised millions in personal and institutional contributions to halt the slide. They marched across the street and ceremoniously bought stocks at inflated prices. The market temporarily stabilized but fears spread over the weekend and the following week frightened investors dumped their portfolios to avoid further losses. On October 29, Black Tuesday, the stock market began its long precipitous fall. Stock values evaporated. Shares of U.S. Steel dropped from $262 to $22. General Motors stock fell from $73 a share to $8. Four fifths of J. D. Rockefeller’s fortune—the greatest in American history—vanished.

Although the crash stunned the nation, it exposed the deeper, underlying problems with the American economy in the 1920s. The stock market’s popularity grew throughout the decade, but only 2.5 percent of Americans had brokerage accounts; the overwhelming majority of Americans had no direct personal stake in Wall Street. The stock market’s collapse, no matter how dramatic, did not by itself depress the American economy. Instead, the crash exposed a great number of factors that, when combined with the financial panic, sank the American economy into the greatest of all economic crises. Rising inequality, declining demand, rural collapse, overextended investors, and the bursting of speculative bubbles all conspired to plunge the nation into the Great Depression.

Despite resistance by Progressives, the vast gap between rich and poor accelerated throughout the early twentieth century. In the aggregate, Americans were better off in 1929 than in 1920. Per capita income had risen 10 percent for all Americans, but 75 percent for the nation’s wealthiest citizens.45 The return of conservative politics in the 1920s reinforced federal fiscal policies that exacerbated the divide: low corporate and personal taxes, easy credit, and depressed interest rates overwhelmingly favored wealthy investors who, flush with cash, spent their money on luxury goods and speculative investments in the rapidly rising stock market.

The pro-business policies of the 1920s were designed for an American economy built on the production and consumption of durable goods. Yet by the late 1920s, much of the market was saturated. The boom of automobile manufacturing, the great driver of the American economy in the 1920s, slowed as fewer and fewer Americans with the means to purchase a car had not already done so. More and more, the well-to-do had no need for the new automobiles, radios, and other consumer goods that fueled gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the 1920s. When products failed to sell, inventories piled up, manufacturers scaled back production, and companies fired workers, stripping potential consumers of cash, blunting demand for consumer goods, and replicating the downward economic cycle. The situation was only compounded by increased automation and rising efficiency in American factories. Despite impressive overall growth throughout the 1920s, unemployment hovered around 7 percent throughout the decade, suppressing purchasing power for a great swath of potential consumers.46

While a manufacturing innovation, Henry Ford’s assembly line produced so many cars as to flood the automobile market in the 1920s. Wikimedia.

For American farmers, meanwhile, hard times began long before the markets crashed. In 1920 and 1921, after several years of larger-than-average profits, farm prices in the South and West continued their long decline, plummeting as production climbed and domestic and international demand for cotton, foodstuffs, and other agricultural products stalled. Widespread soil exhaustion on western farms only compounded the problem. Farmers found themselves unable to make payments on loans taken out during the good years, and banks in agricultural areas tightened credit in response. By 1929, farm families were overextended, in no shape to make up for declining consumption, and in a precarious economic position even before the Depression wrecked the global economy.47

Despite serious foundational problems in the industrial and agricultural economy, most Americans in 1929 and 1930 still believed the economy would bounce back. In 1930, amid one of the Depression’s many false hopes, President Herbert Hoover reassured an audience that “the depression is over.”48 But the president was not simply guilty of false optimism. Hoover made many mistakes. During his 1928 election campaign, Hoover promoted higher tariffs as a means for encouraging domestic consumption and protecting American farmers from foreign competition. Spurred by the ongoing agricultural depression, Hoover signed into law the highest tariff in American history, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, just as global markets began to crumble. Other countries responded in kind, tariff walls rose across the globe, and international trade ground to a halt. Between 1929 and 1932, international trade dropped from $36 billion to only $12 billion. American exports fell by 78 percent. Combined with overproduction and declining domestic consumption, the tariff exacerbated the world’s economic collapse.49

But beyond structural flaws, speculative bubbles, and destructive protectionism, the final contributing element of the Great Depression was a quintessentially human one: panic. The frantic reaction to the market’s fall aggravated the economy’s other many failings. More economic policies backfired. The Federal Reserve overcorrected in their response to speculation by raising interest rates and tightening credit. Across the country, banks denied loans and called in debts. Their patrons, afraid that reactionary policies meant further financial trouble, rushed to withdraw money before institutions could close their doors, ensuring their fate. Such bank runs were not uncommon in the 1920s, but in 1930, with the economy worsening and panic from the crash accelerating, 1,352 banks failed. In 1932, nearly 2,300 banks collapsed, taking personal deposits, savings, and credit with them.50

The Great Depression was the confluence of many problems, most of which had begun during a time of unprecedented economic growth. Fiscal policies of the Republican “business presidents” undoubtedly widened the gap between rich and poor and fostered a standoff over international trade, but such policies were widely popular and, for much of the decade, widely seen as a source of the decade’s explosive growth. With fortunes to be won and standards of living to maintain, few Americans had the foresight or wherewithal to repudiate an age of easy credit, rampant consumerism, and wild speculation. Instead, as the Depression worked its way across the United States, Americans hoped to weather the economic storm as best they could, hoping for some relief from the ever-mounting economic collapse that was strangling so many lives.

XII. Herbert Hoover and the Politics of the Depression

Unemployed men queued outside a depression soup kitchen opened in Chicago by Al Capone. February 1931. Wikimedia.

As the Depression spread, public blame settled on President Herbert Hoover and the conservative politics of the Republican Party. In 1928, having won the presidency in a landslide, Hoover had no reason to believe that his presidency would be any different than that of his predecessor, Calvin Coolidge, whose time in office was marked by relative government inaction, seemingly rampant prosperity, and high approval ratings.51 Hoover entered office on a wave of popular support, but by October 1929 the economic collapse had overwhelmed his presidency. Like all too many Americans, Hoover and his advisors assumed—or perhaps simply hoped—that the sharp financial and economic decline was a temporary downturn, another “bust” of the inevitable boom-bust cycles that stretched back through America’s commercial history. “Any lack of confidence in the economic future and the basic strength of business in the United States is simply foolish,” he said in November.52 And yet the crisis grew. Unemployment commenced a slow, sickening rise. New-car registrations dropped by almost a quarter within a few months.53 Consumer spending on durable goods dropped by a fifth in 1930.54

When suffering Americans looked to Hoover for help, Hoover could only answer with volunteerism. He asked business leaders to promise to maintain investments and employment and encouraged state and local charities to assist those in need. Hoover established the President’s Organization for Unemployment Relief, or POUR, to help organize the efforts of private agencies. While POUR urged charitable giving, charitable relief organizations were overwhelmed by the growing needs of the many multiplying unemployed, underfed, and unhoused Americans. By mid-1932, for instance, a quarter of all of New York’s private charities closed: they had simply run out of money. In Atlanta, solvent relief charities could only provide $1.30 per week to needy families. The size and scope of the Depression overpowered the radically insufficient capacity of private volunteer organizations to mediate the crisis.55

Although Hoover is sometimes categorized as a “business president” in line with his Republican predecessors, he also embraced a kind of business progressivism, a system of voluntary action called associationalism that assumed Americans could maintain a web of voluntary cooperative organizations dedicated to providing economic assistance and services to those in need. Businesses, the thinking went, would willingly limit harmful practice for the greater economic good. To Hoover, direct government aid would discourage a healthy work ethic while associationalism would encourage the self-control and self-initiative that fueled economic growth. But when the Depression exposed the incapacity of such strategies to produce an economic recovery, Hoover proved insufficiently flexible to recognize the limits of his ideology.56 “We cannot legislate ourselves out of a world economic depression,” he told Congress in 1931.57

Hoover resisted direct action. As the crisis deepened, even bankers and businessmen and the president’s own advisors and appointees all pleaded with him to use the government’s power to fight the Depression. But his conservative ideology wouldn’t allow him to. He believed in limited government as a matter of principle. Senator Robert Wagner of New York said in 1931 that the president’s policy was “to do nothing and when the pressure becomes irresistible to do as little as possible.”58 By 1932, with the economy long since stagnant and a reelection campaign looming, Hoover, hoping to stimulate American industry, created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to provide emergency loans to banks, building-and-loan societies, railroads, and other private industries. It was radical in its use of direct government aid and out of character for the normally laissez-faire Hoover, but it also bypassed needy Americans to bolster industrial and financial interests. New York congressman Fiorello LaGuardia, who later served as mayor of New York City, captured public sentiment when he denounced the RFC as a “millionaire’s dole.”59

XII. The Lived Experience of the Great Depression

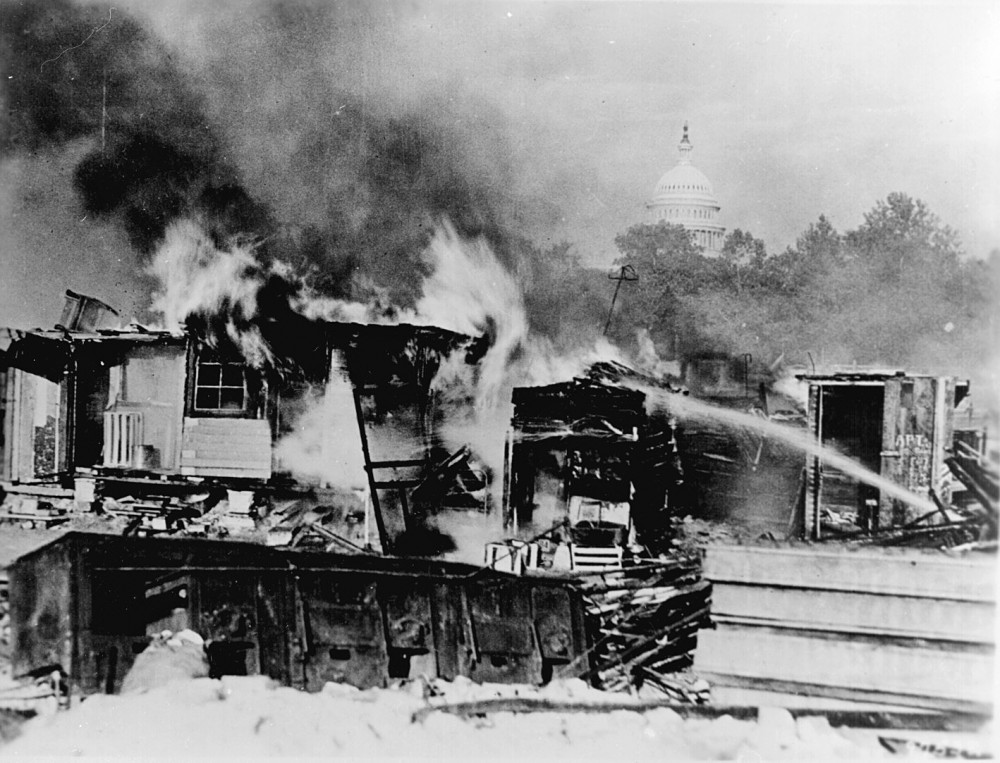

A Hooverville in Seattle, Washington between 1932 and 1937. Washington State Archives.

In 1934 a woman from Humboldt County, California, wrote to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt seeking a job for her husband, a surveyor, who had been out of work for nearly two years. The pair had survived on the meager income she received from working at the county courthouse. “My salary could keep us going,” she explained, “but—I am to have a baby.” The family needed temporary help, and, she explained, “after that I can go back to work and we can work out our own salvation. But to have this baby come to a home full of worry and despair, with no money for the things it needs, is not fair. It needs and deserves a happy start in life.”60

As the United States slid ever deeper into the Great Depression, such tragic scenes played out time and time again. Individuals, families, and communities faced the painful, frightening, and often bewildering collapse of the economic institutions on which they depended. The more fortunate were spared the worst effects, and a few even profited from it, but by the end of 1932, the crisis had become so deep and so widespread that most Americans had suffered directly. Markets crashed through no fault of their own. Workers were plunged into poverty because of impersonal forces for which they shared no responsibility.

With rampant unemployment and declining wages, Americans slashed expenses. The fortunate could survive by simply deferring vacations and regular consumer purchases. Middle- and working-class Americans might rely on disappearing credit at neighborhood stores, default on utility bills, or skip meals. Those who could borrowed from relatives or took in boarders in homes or “doubled up” in tenements. But such resources couldn’t withstand the unending relentlessness of the economic crisis. As one New York City official explained in 1932,

When the breadwinner is out of a job he usually exhausts his savings if he has any.… He borrows from his friends and from his relatives until they can stand the burden no longer. He gets credit from the corner grocery store and the butcher shop, and the landlord forgoes collecting the rent until interest and taxes have to be paid and something has to be done. All of these resources are finally exhausted over a period of time, and it becomes necessary for these people, who have never before been in want, to go on assistance.61

But public assistance and private charities were quickly exhausted by the scope of the crisis. As one Detroit city official put it in 1932,

Many essential public services have been reduced beyond the minimum point absolutely essential to the health and safety of the city.… The salaries of city employees have been twice reduced … and hundreds of faithful employees … have been furloughed. Thus has the city borrowed from its own future welfare to keep its unemployed on the barest subsistence levels.… A wage work plan which had supported 11,000 families collapsed last month because the city was unable to find funds to pay these unemployed—men who wished to earn their own support. For the coming year, Detroit can see no possibility of preventing wide-spread hunger and slow starvation through its own unaided resources.62

These most desperate Americans, the chronically unemployed, encamped on public or marginal lands in “Hoovervilles,” spontaneous shantytowns that dotted America’s cities, depending on bread lines and street-corner peddling. One doctor recalled that “every day … someone would faint on a streetcar. They’d bring him in, and they wouldn’t ask any questions.… they knew what it was. Hunger.”63

Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990), chap. 5).)) “A man is not a man without work,” one of the jobless told an interviewer.64 The ideal of the “male breadwinner” was always a fiction for poor Americans, and, during the crisis, women and young children entered the labor force, as they always had. But, in such a labor crisis, many employers, subscribing to traditional notions of male bread-winning, were less likely to hire married women and more likely to dismiss those they already employed.65 As one politician remarked at the time, the woman worker was “the first orphan in the storm.”66

American suppositions about family structure meant that women suffered disproportionately from the Depression. Since the start of the twentieth century, single women had become an increasing share of the workforce, but married women, Americans were likely to believe, took a job because they wanted to and not because they needed it. Once the Depression came, employers were therefore less likely to hire married women and more likely to dismiss those they already employed.67 Women on their own and without regular work suffered a greater threat of sexual violence than their male counterparts; accounts of such women suggest they depended on each other for protection68

The Great Depression was particularly tough for nonwhite Americans. “The Negro was born in depression,” one Black pensioner told interviewer Studs Terkel. “It didn’t mean too much to him. The Great American Depression . . . only became official when it hit the white man.” ((Studs Terkel, Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (New York: Pantheon Books, 1970), 81-82.)) Black workers were generally the last hired when businesses expanded production and the first fired when businesses experienced downturns. As a National Urban League study found, “So general is this practice that one is warranted in suspecting that it has been adopted as a method of relieving unemployment of whites without regard to the consequences upon Negroes.”69 In 1932, with the national unemployment average hovering around 25 percent, Black unemployment reached as high as 50 percent, while even Black workers who kept their jobs saw their already low wages cut dramatically.70

XIV. Migration and the Great Depression

On the Great Plains, environmental catastrophe deepened America’s longstanding agricultural crisis and magnified the tragedy of the Depression. Beginning in 1932, severe droughts hit from Texas to the Dakotas and lasted until at least 1936. The droughts compounded years of agricultural mismanagement. To grow their crops, Plains farmers had plowed up natural ground cover that had taken ages to form over the surface of the dry Plains states. Relatively wet decades had protected them, but, during the early 1930s, without rain, the exposed fertile topsoil turned to dust, and without sod or windbreaks such as trees, rolling winds churned the dust into massive storms that blotted out the sky, choked settlers and livestock, and rained dirt not only across the region but as far east as Washington, D.C., New England, and ships on the Atlantic Ocean. The Dust Bowl, as the region became known, exposed all-too-late the need for conservation. The region’s farmers, already hit by years of foreclosures and declining commodity prices, were decimated.71 For many in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Arkansas who were “baked out, blown out, and broke,” their only hope was to travel west to California, whose rains still brought bountiful harvests and—potentially—jobs for farmworkers. It was an exodus. Oklahoma lost 440,000 people, or a full 18.4 percent of its 1930 population, to outmigration.72

This iconic 1936 photograph by Dorothea Lange of a destitute, thirty-two-year-old mother of seven made real the suffering of millions during the Great Depression. Library of Congress.

Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother became one of the most enduring images of the Dust Bowl and the ensuing westward exodus. Lange, a photographer for the Farm Security Administration, captured the image at a migrant farmworker camp in Nipomo, California, in 1936. In the photograph a young mother stares out with a worried, weary expression. She was a migrant, having left her home in Oklahoma to follow the crops to the Golden State. She took part in what many in the mid-1930s were beginning to recognize as a vast migration of families out of the southwestern Plains states. In the image she cradles an infant and supports two older children, who cling to her. Lange’s photo encapsulated the nation’s struggle. The subject of the photograph seemed used to hard work but down on her luck, and uncertain about what the future might hold.

The Okies, as such westward migrants were disparagingly called by their new neighbors, were the most visible group who were on the move during the Depression, lured by news and rumors of jobs in far-flung regions of the country. Men from all over the country, some abandoning families, hitched rides, hopped freight cars, or otherwise made their way around the country. By 1932, sociologists were estimating that millions of men were on the roads and rails traveling the country.73 Popular magazines and newspapers were filled with stories of homeless boys and the veterans-turned-migrants of the Bonus Army commandeering boxcars. Popular culture, such as William Wellman’s 1933 film, Wild Boys of the Road, and, most famously, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, published in 1939 and turned into a hit movie a year later, captured the Depression’s dislocated populations.

These years witnessed the first significant reversal in the flow of people between rural and urban areas. Thousands of city dwellers fled the jobless cities and moved to the country looking for work. As relief efforts floundered, many state and local officials threw up barriers to migration, making it difficult for newcomers to receive relief or find work. Some state legislatures made it a crime to bring poor migrants into the state and allowed local officials to deport migrants to neighboring states. In the winter of 1935–1936, California, Florida, and Colorado established “border blockades” to block poor migrants from their states and reduce competition with local residents for jobs. A billboard outside Tulsa, Oklahoma, informed potential migrants that there were “NO JOBS in California” and warned them to “KEEP Out.”74

During her assignment as a photographer for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Dorothea Lange documented the movement of migrant families forced from their homes by drought and economic depression. This family, captured by Lange in 1938, was in the process of traveling 124 miles by foot, across Oklahoma, because the father was ill and therefore unable to receive relief or WPA work. Library of Congress.