8 Chapter 8: Language and Culture

Learning Outcomes

After studying this chapter, you should be able to discuss:

- the definition of dialect and the types of dialects

- accents and their connection to dialect

- the definition of register

- the ways language changes

Dialect

Dialects and accents can vary by region, class, or ancestry, and they influence the impressions that we make of others. Research shows that people tend to think more positively about others who speak with a dialect similar to their own and think more negatively about people who speak differently. Of course, many people think they speak normally and perceive others to have an accent or dialect.

A dialect is a variety of a language that is spoken by a particular group of people. Although dialects include the use of different words and phrases, it’s the tone of voice that often creates the strongest impression. For example, a person who speaks with a Southern accent may perceive a New Englander’s accent to be grating, harsh, or rude because the pitch is more nasal and the rate faster. Conversely, a New Englander may perceive a Southerner’s accent to be syrupy and slow, leading to an impression that the person speaking is uneducated. Accent is the particular way words are pronounced. It’s important to note that accent is just one part of a particular dialect.

The term ‘dialect’ can be considered as a head term for various types of dialects. These can be defined on the basis of the type of variation from the standard language:

- Regional dialect

- Social dialect

- Phonological dialect

What’s the difference between a language, a dialect, and an accent?

Regional Dialects

Mostly, the term dialect is associated with some sort of regional difference between the speakers of a language. Their use of their language identifies their regional background.

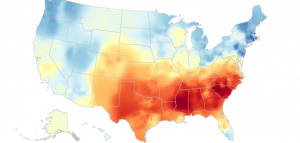

The United States has a great number of regional dialects. Many of them are based on geographic region of the country. Linguists can even tell with a reasonable degree of certainty where you are from based on your answers to questions like, “How would you address a group of people?” A linguist named Bert Vaux designed the Harvard Dialect Survey in the 1990s to do just this. It went online in 2002, revised with the help of Scott Golder, and was published by the New York Times in 2013 .

These regional differences in America are a result of the immigrants who settled into these areas and the migration routes of other settlers as they moved west to settle in new areas.

The first permanent English settlement of the New World began with the arrival of England’s second expedition in 1607. (Sir Walter Raleigh and his fellow-explorers, who arrived in 1584, had been forced to return to England as a consequence of conflicts with the native people). These ‘southern’ colonists came mainly from England’s ‘West Country’. Their ‘Tidewater Accents’ still exist today in some isolated valleys; this ‘variety’ is said to be the closest to the sound of Shakespeare’s English. Thus, it can be said that the first ‘variety’ of English spoken in North America was Early Modern English (or Shakespearean English). Then, in 1620, the first group of Puritans arrived on the Mayflower. These people did not want to return to England.

1681 brought new shiploads of immigrants, Quakers from the North of England and the North Midlands, who settled in Pennsylvania. Later there was a vast wave of immigration from northern Ireland and Scotland to this area. By the time independence was declared (1776), one in seven of the colonial population was Scots-Irish.

This video gives a great explanation of how these immigrants’ languages have influenced American dialects:

Here’s part II:

This video from the 1950s demonstrates some differences in common American dialects.

What follows are some examples of different United States dialects. Remember that a dialect includes both accent variation and other linguistic variations. Some of the videos refer to dialects as simply accents, but, if you pay attention, you’ll notice how vocabulary and usage are different, as well.

Northeastern American English

The Northeastern United States has a wide variety of distinct accents and dialects. The diversity that exists in the modern Northeast is partially a consequence of its older settlement history: communities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia have been around longer than similar-sized communities in the Western U.S. As a result, the speech of each urban community has had more time to diverge from the dialects of other nearby cities.

Smith Island, Maryland

Philadelphia

Moms of the Northeast

Pacific Northwest

Arizona

https://youtube.com/watch?v=FUkAhTIIFBU

Okracoke Brogue

The Okracoke brogue of North Carolina, which is disappearing, is an great example of how the origins of early immigrants to the US influenced the way language developed. After watching the video, check out the comments from folks in England who identify British dialects in the Okracoke brogue.

Southern States English

The term Southern States English refers to a number of varieties of English spoken in many of the Southern States, including Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Tennessee, North and South Carolina, Virginia, and parts of Arkansas, Maryland, Oklahoma, Texas, and West Virginia. Although these varieties are not uniform throughout these states, they share certain common characteristics that differentiate them from other varieties found in the Northern and Western United States.

Dialects were also influenced by speakers of other languages as settlers moved into new areas. Ways of speaking and words were borrowed from contact with speakers of Spanish, French, Native American languages, as well as enslaved peoples of African descent who spoke their native languages. Geographic boundaries (islands, mountains) would have kept some of these ways of speaking linguistically isolated from others (Light, 2018). (see the video below about the accent of Tangier Island, VA).

This PBS site explores more American dialects.

Social Dialects

When two people speak with one another, there is always more going on than just conveying a message. The language used by the participants is always influenced by a number of social factors which define the relationship between the participants. These factors must be considered in order to effectively convey the message to the other participant. They influence the choice of variety or ‘code’:

- Participants: How well do they know each other?

- Social Setting: formal or informal

- Interlocutors: Status relationship/Social role

- Aim or Purpose of Conversation

- Topic

Communication accommodation theory is a theory that explores why and how people modify their communication to fit situational, social, cultural, and relational contexts (Giles, Taylor, & Bourhis, 1973). Within communication accommodation, conversational partners may use convergence, meaning a person makes his or her communication more like another person’s. People who are accommodating in their communication style are seen as more competent, which illustrates the benefits of communicative flexibility. In order to be flexible, of course, people have to be aware of and monitor their own and others’ communication patterns. Conversely, conversational partners may use divergence, meaning a person uses communication to emphasize the differences between themselves and their conversational partner.

Convergence and divergence can take place within the same conversation and may be used by one or both conversational partners. Convergence functions to make others feel at ease, to increase understanding, and to enhance social bonds. Divergence may be used to intentionally make another person feel unwelcome or perhaps to highlight a personal, group, or cultural identity.

For example, African American women use certain verbal communication patterns when communicating with other African American women as a way to highlight their racial identity and create group solidarity. In situations where multiple races interact, the women usually don’t use those same patterns, instead accommodating the language patterns of the larger group.

While communication accommodation might involve anything from adjusting how fast or slow you talk to how long you speak during each turn, code-switching refers to changes in accent, dialect, or language (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). There are many reasons that people might code-switch.

Gender

In addition to geographic location, how we speak is often related to our age, as well as gender and ethnicity. For example, females are more likely to use “high rise terminal” or uptalk, which turns a declarative sentence into a question. (Say these two sentences aloud to hear an example: “The sky is blue.” “The sky is blue?”)

Females are also thought to use vocal fry more. Vocal fry, or the creaky voice (see click below), is the dropping of the pitch at the end of a word or phrase. It’s primarily associated with the Kardashians, but traces its roots to the 2000s with the way Paris Hilton speaks.

Uptalk and vocal fry are thought to be “obnoxious” or “unprofessional” by most people. National Public Radio’s “This American Life” received a number of complaints about female reports using vocal fry, but no one complained about the vocal fry of the host, Ira Glass. In fact, all genders use uptalk and vocal fry, though it is most associated with young women. Linguists have found that vocal fry and uptalk signal submissiveness or being non-threatening in social situations. Studies have found that while some see these vocal patterns as unprofessional, many young women perceive it as belonging to an upwardly mobile and well-educated group of women.

Ethnicity

Our ethnicity may also shape how we speak.

African American Vernacular English

African American Vernacular English (AAVE) is an example. This linguistic variety is also referred to as Black English (BE), Black English Vernacular (BEV), African-American Vernacular English (AAVE), Inner City English (ICE), or Ebonics.

AAVE is thought to have originated among polyglot enslaved Africans exposed to the English of the upper classes and poor whites, as it includes features of West African languages, Standard English, and non-standard English dialects of the 17th century British Isles.

There are three primary theories regarding the source of African-American English:

- Decreolized Creole:

Proponents of the decreolized creole theory maintain that African-American English arose from a pidgin that was created among slaves from various linguistic backgrounds, primarily from West Africa. This pidgin included features of both the West African languages and English. Over time, this pidgin developed into a creole, and then more recently, became decreolized, and began to resemble English more closely. - Variety of Southern States English:

Others state that African-American English is a variety of Southern States English, noting that the two varieties have many features in common, such as the Southern Vowel Shift or vowel lowering. - The “Unified” Theory:

Proponents of the unified theory state that African-American English arose from a number of sources, including West African languages and Southern States English, along a variety of evolutionary tracks.

Though viewed as not standard English, AAVE is a complex and functional language. It has its own grammatical rules, vocabulary, and pronunciations. It as just as much a vernacular as standard English, Scottish English, or a Southern accent.

American Indian English

The term American Indian English (AIE) refers to a number of varieties of English that are spoken by indigenous communities throughout North America. Each one is unique in its phonology, syntax and semantic properties. Examples of AIE are Mojave English, Isletan English, Tsimshian English, Lumbee English, Tohono O’odham English, and Inupiaq English. These varieties of American English can be associated with the following phonological features (but not all features are associated with all varieties of AIE):

- The central diphthong

- Final devoicing

- Deletion of final voiced stops

- Consonant cluster reduction

It has been proposed that the features of American Indian English either originate from the same sources as other nonstandard varieties of English, such as Southern States English or that features of American Indian English are the result of influence from the native language.

Here is an excerpt of a video describing the origins of the indigenous tribes in North America:

Sexuality

LGBT linguistics is the study of language as used by members of LGBT communities. “Language”, in this context, may refer to any aspect of spoken or written linguistic practices, including speech patterns and pronunciation, use of certain vocabulary, and, in a few cases, an elaborate alternative lexicon.

Traditionally it was believed that one’s way of speaking is a result of one’s identity, but the postmodernist approach reversed this theory to suggest that the way we talk is a part of identity formation, specifically suggesting that gender identity is variable and not fixed. There was a shift in beliefs from language being a result of identity to language being employed to reflect a shared social identity and even to create sexual or gender identities. The following video gives a balanced, linguistic perspective on this topic.

Phonological

Strictly speaking, a phonological dialect or accent differs from the standard language only in terms of its pronunciation.

The two variants: He did it vs. He done it are thus true dialectal variants, since more than just the pronunciation differs. Usually speakers of different dialects have different accents, too.

Accents are distinct styles of pronunciation (Lustig & Koester, 2006). There can be multiple accents within one dialect. For example, people in the Appalachian Mountains of the eastern United States speak a dialect of American English that is characterized by remnants of the linguistic styles of Europeans who settled the area a couple hundred years earlier. Even though they speak this similar dialect, a person in Kentucky could still have an accent that is distinguishable from a person in western North Carolina.

Regarding accents, some people hire vocal coaches or speech-language pathologists to help them alter their accent. If a Southern person thinks their accent is leading others to form unfavorable impressions, they can consciously change their accent with much practice and effort. Once their ability to speak without their Southern accent is honed, they may be able to switch very quickly between their native accent when speaking with friends and family and their modified accent when speaking in professional settings.

In the early 20th century, a new accent was created specifically for actors:

Register

In sociolinguistics, a register is a variety of language used for a particular purpose or in a particular communicative situation. For example, when speaking officially or in a public setting, an English speaker may be more likely to follow prescriptive norms for formal usage than in a casual setting, for example, by pronouncing words ending in -ing with a velar nasal instead of an alveolar nasal (e.g., “walking” rather than “walkin'”), choosing words that are considered more “formal” (such as father vs. dad or child vs. kid), and refraining from using words considered nonstandard, such as ain’t and y’all.

As with other types of language variation, there tends to be a spectrum of registers rather than a discrete set of obviously distinct varieties—numerous registers can be identified, with no clear boundaries between them. Due to this complexity, scholarly consensus has not been reached for the definitions of terms such as “register,” “field,” or “tenor”; different scholars’ definitions of these terms are often in direct contradiction of each other.

Additional terms such as diatype, genre, text types, style, acrolect, mesolect, basilect, sociolect, and ethnolect, among many others, may be used to cover the same or similar ground. Some prefer to restrict the domain of the term “register” to a specific vocabulary (which one might commonly call slang, jargon, argot, or cant), while others argue against the use of the term altogether. These various approaches with their own “register,” or set of terms and meanings, fall under disciplines such as sociolinguistics.

Slang/Jargon

In defining register as a specific vocabulary (slang or jargon), occupational registers might come to mind. A community college professor in Arizona, for example, will know that the AGEC is the Arizona General Education Curriculum and that the ATF refers to Arizona Transfer, and not Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms. Such registers can both create a cohesive understanding among members of a particular group, but it can also have the effect of excluding people from that group. For example, when faculty members discuss particular educational issues, students might feel they are hearing a foreign language.

This example of teacher jargon is pretty entertaining:

Another example of a register that might exclude a population who needs to understand the language is the medical profession. Medical professionals often speak in medical terms that patients might not be able to understand. While the language is necessary for doctors and nurses to communicate accurately, patients need to be educated about jargon that impacts their care.

The Language of Gamers

Gamer Speak is another example of a register based around a shared vocabulary.

Watch this video. Is she speaking English?

Here’s an explanation of how Gaming language evolved:

This site explores the unique language of gamers.

The language of gamers is just one example of how a particular hobby or career can create its own jargon or register. What registers do you use?

Language & Culture

Language Change

When languages meet, they change. More importantly, they often change each other. As we’ve learned, new words can be created as a result of languages and cultures mixing. Sometimes dialects and even new languages can form because of an interaction with another language/culture. Unfortunately, the meeting of cultures can also cause the extinction of languages, as one group dominates the other, as with many indigenous languages. Why is this important? Because often language is intimately tied to culture and identity. Blurring the Lines argues that language and culture are interwined.

Code-Switching

Increasing outsourcing and globalization have produced heightened pressures for code-switching. Call center workers in India have faced strong negative reactions from British and American customers who insist on “speaking to someone who speaks English.” Although many Indians learn English in schools as a result of British colonization, their accents prove to be off-putting to people who want to get their cable package changed or book an airline ticket.

Now some Indian call center workers are going through intense training to be able to code-switch and accommodate the speaking style of their customers. What is being called the “Anglo-Americanization of India” entails “accent-neutralization,” lessons on American culture (using things like Sex and the City DVDs), and the use of Anglo-American-sounding names like Sean and Peggy (Pal, 2004).

As our interactions continue to occur in more multinational contexts, the expectations for code-switching and accommodation are sure to increase. It is important for us to consider the intersection of culture and power and think critically about the ways in which expectations for code-switching may be based on cultural biases.

Pidgins

Not only can the connection of different cultures cause small changes in a language, they can also result in the creation of a new “bridge” language. An example of such a situation can be found with pidgins. Pidgins are not full languages, but communication systems with the bare minimum ability to communicate, usually for a specific context, like trade or colonialism. They are not spoken by anyone as a first language and are not learned by children. They’re only learned by adults for a specific application, and, for this reason, have risen in many colonial situations. For example, an English based pigeon in Canton and Guangdong China emerged when there was a large European presence in the region, but neither group needed or wanted to properly learn the other’s language. So, speakers of the languages made do with creating a pidgin that started in the 18th century. It had mostly English words with some Chinese grammar and a few words of Portuguese. The phrase, “sen one piece cooly come my sop look see” in the pidgin would translate to “send a servant to come to my shop and see.”

Creoles

A pidgin can become a full language. The result is called a creole. Creoles are learned by children, and there are full rules of grammar. There are a number of creoles spoken in the US including Gullah, which is spoken mostly off the coast of the Carolinas. Gullah was created from the pidgin spoken by enslaved West Africans and white plantation owners, and a Creole spoken in Hawaii, which is confusingly referred to as a pigeon. There is also a family of Caribbean English-based Creoles including Jamaican Patois, which is related to Gullah and developed for similar reasons. As such, it contains words from Scottish and other non-standard dialects of English that were picked up by enslaved people from the indentured servants who they worked alongside.

Language Extinction

Another aspect of language change is language extinction. There are currently 6,000 to 7,000 languages in existence today, but, in the next 100 years, over 80% of these could become extinct. Languages die because of contact with a larger, more powerful groups. For example, the indigenous residents of the British Isles spoke a Celtic language. Aspects of this language were incorporated into the Latin spoken in the area after the Roman invasion, which was then incorporated into the Germanic languages spoken by German invaders, with a bit of sprinkling of Viking language from their invasion. Together these became Old English.

If languages do not evolve into other languages, they become dead ends. This limits the diversity of the world because we know language, culture, and thought are intricately connected. Groups speaking languages facing extinction have sought revitalization efforts, such as teaching their language to the next generation. A project to protect the Omaha and Ponca languages was undertaken in 2006 to teach the language to college students and the larger community. You can explore the site here.

Indigenous people have been working for years to try to preserve their languages by increasing the number of people who can speak them. People with Linguistics training can play a valuable role in language preservation and revitalization efforts by helping to document the language and by contributing to the development of teaching materials for the languages.

Connections: Arizona’s Indigenous Languages

Navajo: Dark Winds has been criticized for its lack of authenticity.

Yavapai: Preserving Language is More than Just Words; The Yavapai Voice, A Struggle for Distinction; Havasupai Habitat;

White Mountain Apache: Issues in Language Shift

Attributions:

Content in this chapter adapted from the following:

“Language and Communication” by Taylor Livingston Licensed CC BY NC.

VLC205-Varieties of English

by Jürgen Handke, Peter Franke, Linguistic Engineering Team under CC BY 4.0

Essentials of Linguistics by Catherine Anderson licensed CC BY SA 4.0.

Communication in the Real World by University of Minnesota is licensed under CC BY NC SA.

LGBT Linguistics licensed CC BY SA.

References:

- Hockett, (1960) The Origin of Speech, Scientific American203, 88–111Reprinted in: Wang, William S-Y. (1982) Human Communication: Language and Its Psychobiological Bases, Scientific American pp. 4–1

- James, B. (2018). A Sneaky Theory of Where Language Came From. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/06/toolmaking-language-brain/562385/

-

Labov, W. 1972. The Social Stratification of (r) in New York City Department Stores. Sociolingusitic Patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.Light, L. 2018. Language. Perspectives:An open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 2nd edition. https://perspectives.pressbooks.com/chapter/language/

- Rauschecker JP. (2018). Where did language come from? Precursor mechanisms in nonhuman primates. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2018;21:195-204. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.

- Wesch, M. 2016. The Power of Language. The Art of Being Human. https://anth101.com/language/

- American Psychological Association, “Supplemental Material: Writing Clearly and Concisely,” accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.apastyle.org/manual/supplement/redirects/pubman-ch03.13.aspx.

- Crystal, D., How Language Works: How Babies Babble, Words Change Meaning, and Languages Live or Die (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2005), 155.

- Dindia, K., “The Effect of Sex of Subject and Sex of Partner on Interruptions,” Human Communication Research 13, no. 3 (1987): 345–71.

- Dindia, K. and Mike Allen, “Sex Differences in Self-Disclosure: A Meta Analysis,” Psychological Bulletin 112, no. 1 (1992): 106–24.

- Exploring Constitutional Conflicts, “Regulation of Fighting Words and Hate Speech,” accessed June 7, 2012, http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/conlaw/hatespeech.htm.

- Gentleman, A., “Indiana Call Staff Quit over Abuse on the Line,” The Guardian, May 28, 2005, accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2005/may/29/india.ameliagentleman.

- Giles, H., Donald M. Taylor, and Richard Bourhis, “Toward a Theory of Interpersonal Accommodation through Language: Some Canadian Data,” Language and Society 2, no. 2 (1973): 177–92.

- Kwintessential Limited, “Results of Poor Cross Cultural Awareness,” accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.kwintessential.co.uk/cultural-services/articles/Results of Poor Cross Cultural Awareness.html.

- Lustig, M. W. and Jolene Koester, Intercultural Competence: Interpersonal Communication across Cultures, 2nd ed. (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2006), 199–200.

- Martin, J. N. and Thomas K. Nakayama, Intercultural Communication in Contexts, 5th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2010), 222–24.

- McCornack, S., Reflect and Relate: An Introduction to Interpersonal Communication (Boston, MA: Bedford/St Martin’s, 2007), 224–25.

- Nadeem, S., “Accent Neutralisation and a Crisis of Identity in India’s Call Centres,” The Guardian, February 9, 2011, accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/feb/09/india-call-centres-accent-neutralisation.

- Pal, A., “Indian by Day, American by Night,” The Progressive, August 2004, accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.progressive.org/mag_pal0804.

- Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th ed. (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2010), 71–76.

- Southern Poverty Law Center, “Hate Map,” accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.splcenter.org/get-informed/hate-map.

- Varma, S., “Arbitrary? 92% of All Injuries Termed Minor,” The Times of India, June 20, 2010, accessed June 7, 2012, http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2010-06-20/india/28309628_1_injuries-gases-cases.

- Waltman, M. and John Haas, The Communication of Hate (New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, 2011), 33.

- Wetzel, P. J., “Are ‘Powerless’ Communication Strategies the Japanese Norm?” Language in Society 17, no. 4 (1988): 555–64.

- Wierzbicka, A., “The English Expressions Good Boy and Good Girl and Cultural Models of Child Rearing,” Culture and Psychology 10, no. 3 (2004): 251–78.