Philip Brown

Tenzin Gyatso was born in 1935 to a small rural family in northeastern Tibet. The first two years of his life were uneventful—that is, until he was two years old, when he was recognized as the next incarnation the spiritual leader of the Buddhist faith. Ever since that day, he has been known across the world as His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama.

As an adherent of the Buddhist faith, one of the Dharmic religions that holds nonviolence (Ahimsa in Sanskrit) as one of its central precepts, the Dalai Lama has always strived to recognize, respect, and connect to the humanity that lies within all sentient beings, and strives to teach others to adhere to humanistic principles in every aspect of their lives. As the spiritual leader of his people, the Dalai Lama’s influence was initially focused on matters relating to scripture, meditation, and philosophy. This changed with the Chinese invasion and annexation of Tibet in 1950, when his people called upon him to assume the role of the country’s political leader. With this unexpected development, he was catapulted into the world’s political arena during the severest existential crisis Tibet had ever faced. Though the hostilities were quickly ended and Tibet was initially allowed a large degree of autonomy, relations began to deteriorate in 1956, and by 1959 the Dalai Lama was forced to dissolve the local Tibetan government and flee to Dharamsala, India, where he established the Tibetan Government-in-Exile and remains there to the present day.

Despite falling victim to Chinese aggression, regardless of its justification or political validity (which is still being debated), the Dalai Lama has continued to conscientiously object to the treatment of Tibet and raise awareness among the international community of the plight of the Tibetan people. Furthermore, he has endeavored to empower Tibetans by democratizing the Central Tibetan Authority, which he accomplished before resigning his political office in 2011 and devolved political authority to the democratically elected leadership. Throughout his tenure as a political leader and throughout his entire body of philosophical teachings, his resolute commitment to nonviolence in word and deed has become the most revered and distinguished characteristic of his spiritual and secular leadership.

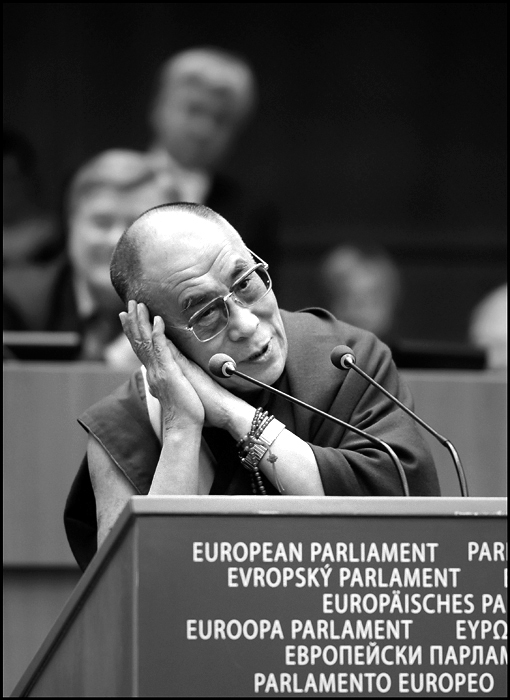

His tenet of nonviolence forms the cornerstone of his “Middle-Way Approach,” which seeks the autonomy of the Tibetan people, allowing them to uphold their democratic values, while remaining within the framework of the People’s Republic of China. This compromise, or “Middle-Way,” is “a non-partisan and moderate position that safeguards the vital interests of all concerned parties” (“The Middle-Way Approach”). The conflict in Tibet has seen great human suffering and injustice, and though the Dalai Lama has never missed an opportunity to bring attention to this issue, he has always maintained a respectful, patient, and compassionate attitude with the Chinese authorities, and his political rhetoric has never hinted at violence or called for retribution. Speaking to the European parliament in Strasbourg in 2001, the Dalai Lama summarized his embodiment and commitment to nonviolent theory and rhetoric as follows:

I have led the Tibetan freedom struggle on a path of non-violence and have consistently sought a mutually agreeable solution of the Tibetan issue through negotiations in a spirit of reconciliation and compromise with China […] While I firmly reject the use of violence as a means in our freedom struggle, we certainly have the right to explore all other political options available to us. I am a staunch believer in freedom and democracy and have therefore been encouraging the Tibetans in exile to follow the democratic process. (Gyatso)

In a lecture he delivered in 2015 entitled “A Human Approach to World Peace,” he expounded further on the fundamental meaning behind his conviction to nonviolence as it compels us to “revive our humanitarian values” because “universal humanitarianism is essential to solve global problems.” His teachings speak to a diverse multi-faith and multicultural audience because his primary motivation has always been to empower people through education, not indoctrination. To avoid the refractory obstacles that arise in the midst of ideological, political, and religious conflicts, the Dalai Lama continues to remind his listeners that we must always be mindful of the basic humanity that binds us all together.

Sources

- “A Human Approach to World Peace.” The 14th Dalai Lama.

- Gyatso, Tenzin. “Peace.” Vital Speeches of the Day, vol. 68, no. 3, Nov. 2001, p. 91.

- “The Middle-Way Approach.” The Office of Tibet – Pretoria, July 2005.