Vrixton Phillips

Poetics can be defined as a “theory of poetry” the way oratory or rhetoric can be defined as a “theory of speaking.” There is much argument about how broad or narrow such a definition should be. Just as rhetoric has been broadened from only speaking and persuading into digital media and hypertext, so too have people asked what constitutes a poem in an increasingly technologically advanced era.

There are many ways of measuring a poem: its meter, its form, its purpose, etc. One of the largest divisions of poetry is that between lyric and narrative (or, as in Greek and Roman times, lyric, dramatic, and epic poetry). Where lyric poetry is personal, expressive, and in the first person, narrative poetry tells a story and often has more than one scene.

Aristotle, in his Poetics, says that it is the tragic form that is superior because in addition to being able to use the epic meter (which we call dactylic hexameter) there is also the advantage of music, being vivid both when read and acted, and a tragedy is typically a much shorter work than an epic poem. Even in terms of the “unity” of plot, the tragedy is superior for Aristotle because from a single epic many plots for tragedies can be derived, all about different characters because of the great number of subplots and tangential characters.

The way we measure meter in Western poetry is primarily inherited from Greek poetry. Although English poetry is primarily a stressed language and Greek one in which syllables have long and short lengths, we still maintain their method of scansion involving anapests, dactyls, iambs, etc. A very clever poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge introduces the basic feet of Classical meter this way:

Trochee trips from long to short;

From long to long in solemn sort

Slow Spondee stalks; strong foot! yet ill able

Ever to come up with dactyl trisyllable.

Iambics march from short to long;—

With a leap and a bound the swift Anapæsts throng;

One syllable long, with one short at each side,

Amphibrachys hastes with a stately stride;—

First and last being long, middle short, Amphimacer

Strikes his thundering hoofs like a proud high-bred racer.

These may define the feet, but to define the meter itself one must count them. For example, the most common meter in the English tongue is “iambic pentameter,” a line of verse with five iambs in it. Not all meters are named this way, for historical reasons, such as the Alexandrine (a line of twelve syllables divided in the middle by a caesura, sometimes known in English as iambic hexameter, though they are not always equivalent), which has its origins in the medieval French poem, Roman d’Alexandre.

Not everyone scans poetry the Western way, however. India has its own classical tradition stretching back to ancient times, and one of the six Vedangas (Vedic studies) of Hinduism was an intense study of Sanskrit prosody. Much of the mathematical genius of India is on display here, in the bhashyas (commentaries) on other scholars of Sanskrit prosody, such as Pingala, whose Gaṇa (trisyllabic feet) organization system was set up in what turned out to be binary, bringing one of his commentators to the discovery of what is known in the West as Pascal’s Triangle, more accurately titled Halayudha’s Triangle.

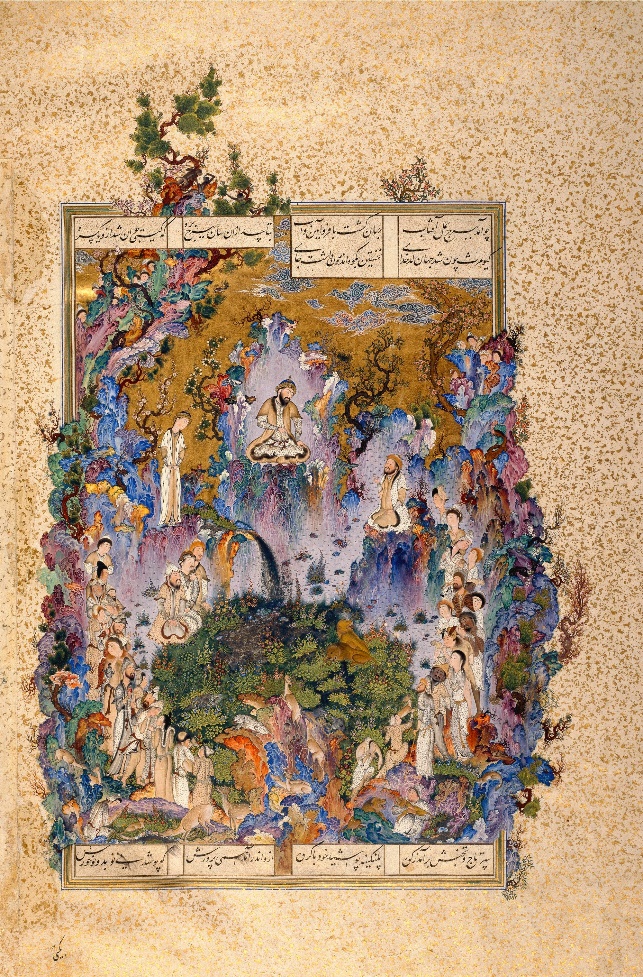

Furthermore, while epic poetry is a staple of Western literature, it is in Sanskrit that the epic truly shines. The Mahabharata is a mammoth epic ten times the length of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey combined, containing 100,000 rhymed couplets, called slokas, for a total of 200,000 lines. This and the other famous epic of Hinduism, The Ramayana, have furnished fodder for an immense number of other epics, including the strange but wonderful genre of South Asian, bi-textual śleṣa poetry described by Yigal Bronner in his book Extreme Poetry, in which two different stories (typically the Mahabharata and the Ramayana) are told simultaneously in the same poem. Another interesting form is the diction called chitrakavya or “picture-poetry,” in which poets draw pictures in their verse by strategically placing certain syllables in a design, sometimes as simple as a drum or a zig-zag, or as complex as a lotus flower, a chariot wheel, or the solution to a chess problem known as “the knight’s tour.”

Of course, poetry is not always incredibly complex. Sometimes, its simplicity and verisimilitude to life is what is valued most, and even in heavily artificial epochs like Tang China or Heian Japan poetry can be lyrical and touching, emotive and picturesque while short and unadorned. Often poetry was a pastime taken up by courtiers to show off their skills with language, to spar with rivals or with paramours as The Tale of Genji by Lady Murasaki Shikibu shows, or the sign of a scholar, along with being able to paint, play Go, and pass the imperial exam. Lady Murasaki Shikibu’s novel, the first novel ever written, is one of love and loss that takes place primarily through the poems passed between Prince Genji and the various women he seduces, with the manners surrounding the wit involved in writing these poems and the drama of reading his lovers’ riddles making much of the slow-burning plot.

Also of note is the history of poetry and poetics. For instance, before English began to adopt French and Classical forms, it was fully Germanic in nature, using alliterative verse like the Norse skalds across the North Sea. Jackson Crawford goes into detail on his video about the art of Viking poetry. More modern attempts to re-create Old and Middle English forms include the poetry of fantasy author and linguist J.R.R. Tolkien, which often involves alliteration and the use of the hemistich or half-line, popular in Germanic and Old English poetry.

Sources

- Aristotle, and James Hutton. Aristotle’s Poetics. Norton, 1982.

- Bronner, Yigal. Extreme Poetry: The South Asian Movement of Simultaneous Narration. Columbia University Press, 2010.

- “Chitrakavya – Chitrabandha.” Sreenivasaraos, 14 June 2020.

- Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. “Metrical Feet.” Bartleby, n.d.

- “Gaṇas.” Learn Sanskrit, n.d.