Women in Rhetoric

Brandy Clouatre

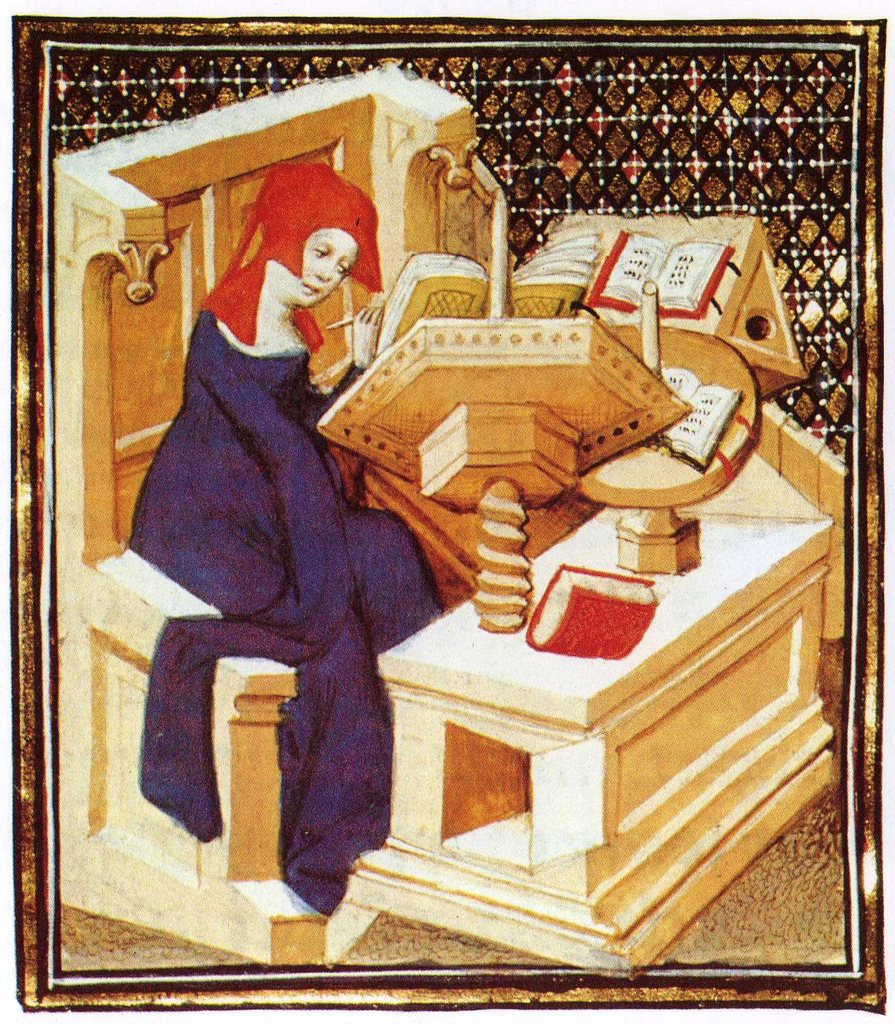

Often when rhetoric is discussed, its contributions lean toward men. However, it is often not realized that women participated in the rhetorical field of study. While women did not contribute to rhetorical theory to the same extent as men, many were born with the natural talent of speaking and writing. Christine de Pizan was born to Thomas de Pisan in Venice, Italy, in 1364 CE. Her father, a scholar, was assigned as an astrologer to French king Charles V. Living for a time in the court of Charles V allowed Christine access to the library and to be among educated people. Through self-education, Christine became a well-read woman in fields that included history, science, and poetry from Greek and Roman authors as well from contemporaries such as Dante and Boccaccio (Herrick 169–170). Language and classical rhetoric were also a part of her reading spectrum that included French, Italian, and Latin. Married at the age of 15 to Etienne du Castel in 1379 CE, she had three children with him. Ultimately, in 1389 CE the plague took her husband’s life, leaving Pizan to turn to writing to support her family, which included her three children, her mother, and a niece (Mark). Her initial poetry writing was dedicated to her late husband; however, she also engaged in political treatises, thus resulting in her title as Europe’s first professional woman writer.

Pizan’s ability as a rhetorician significantly contributed to feminism as she used her platform to correct discriminatory views of women during her time. Through Pizan’s authority, she claimed the right to “talk back” to men. The Book of the City of Ladies, first known as The Treasure of the City of Ladies, was published in 1401 and is Pizan’s most known work. In it, she challenges the writings of misogynist men such as Matheolus: “They all concur in one conclusion: that the behavior of women is inclined to and full of every vice” (Ritchie 34). Through her novel, Pizan questions why God would create such evil creatures that are inferior and incapable of genuine accomplishments. Basing her arguments on religious virtue, Pizan asserts a woman’s right to respect, education, public speech, and writing. Three allegorical women—Reason, Rectitude, and Justice—together with Pizan as the narrator construct a new history of women in contrast to that of her counterparts. Other impactful works of her time by Pizan include The Changes of Fortune (1400–1403) and Vision of Christine (1405).

Christine not only advocated for women’s virtue; she strived to empower women to become more involved in intellectual life: “Women’s success depends on their ability to manage and mediate by speaking and writing effectively” (Herrick 170). Becoming one of the first feminist writers of her time, she believed that all women should have the right to an education. Pizan wrote forty-one known pieces during her time, using the French vernacular. Pizan’s platform encouraged women to challenge the unethical ideas that women were not entitled to rights and were the property of men. Feminism is often seen as something from a more modern era such as the 1960s and the 1970s; however, Pizan is the originator of the first women’s rights movement. While rhetoric and the like did not consider gender, Christine de Pizan opened the doors that built the strong women we have today.

Born during the Hundred Years War, Pizan was inspired to write a treatise called The Book of Feats of Arms and of Chivalry published in 1410 CE. The treatise emphasized how to conduct a just war, the purposes of war, and a means of prevention on war-related matters. From Pizan’s view, women should encourage their husbands not to wage war due to how costly war becomes to everyone over time. However, Christine would not stop there. She later published another novel that stems from her perspective of war called the Book of Peace in 1413 CE. From a woman’s perspective, Pizan wrote about an ethical government, the obligation carried by the government for its people, and suggestions on how to prevent armed conflict (Mark). For a woman, Christine wrote and engaged in subjects that were mostly set out for men in discussion. Acknowledging her desire to learn, Pizan became a great writer of her time in poetry, literary criticism, and on the political sphere—thus contributing to the study of women in rhetoric.

Sources

- Herrick, James A. The History and Theory of Rhetoric: An Introduction. 6th ed., Routledge, 2018.

- Mark, Joshua J. “Christine De Pizan.” Ancient History Encyclopedia, Ancient History Encyclopedia, 8 Nov. 2020, www.ancient.eu/Christine_de_Pizan/.

- Ritchie, Joy S., and Kate Ronald. Available Means: An Anthology of Women’s Rhetoric(s). University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001.