Abigail Logan

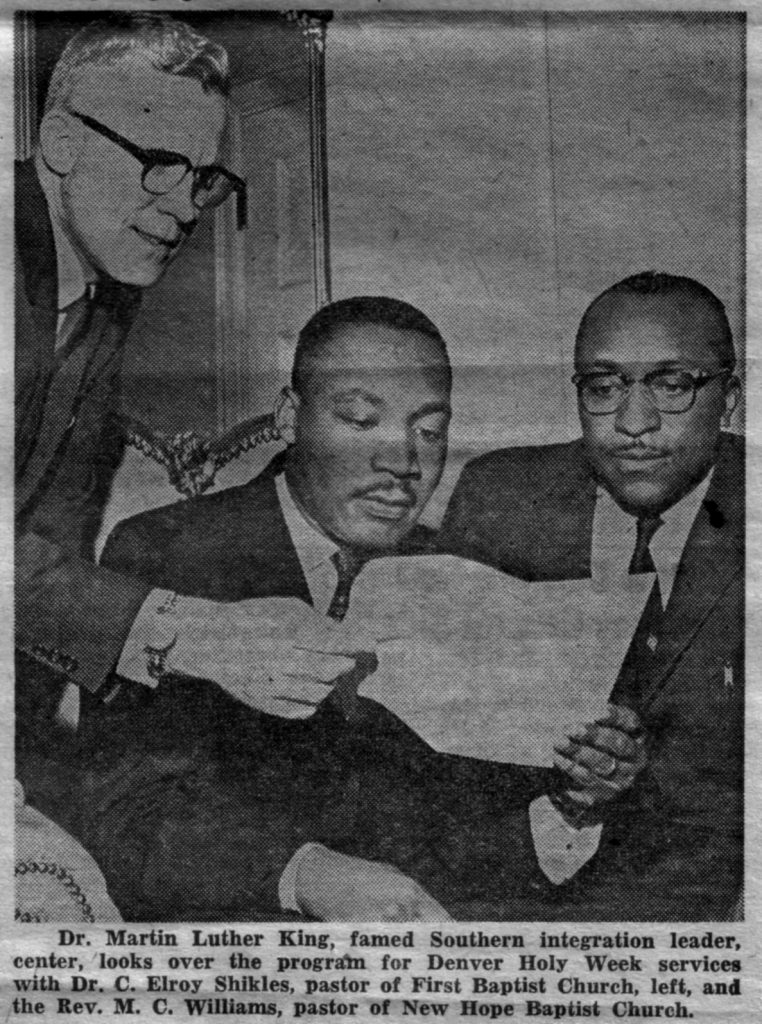

Nonviolent rhetoric is the theory that a peaceful yet determined stance can create more effective and long-lasting change than force or coercion. Much like invitational rhetoric, nonviolent rhetoric is characterized by its focus on empathy and understanding. However, a distinct difference between the two theories is the stance on persuasion. While invitational rhetoric has written off persuasion as violence, nonviolent rhetoric views persuasion more as a tool to be used in a variety of ways, including for promoting equality in social and political relationships. Nonviolent rhetoric was established under the guise that traditional rhetoric can be used to enact changes in life without violence. Despite the lack of recognition in the world of rhetoric, nonviolent rhetoric is by no means a new theory and has play a crucial part in some the greatest social revolutions of the modern age. Historical activists for nonviolent rhetoric include Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., both of whom accomplished their goals without a call to violence or a violent action. King even went on record saying, “Nonviolence is the answer to the crucial political and moral questions of our time; the need for mankind to overcome oppression and violence without resorting to oppression and violence” (Pt’chang). Such sentiments still drive those who advocate for nonviolence today. In her book Peaceful Persuasion: The Geopolitics of Nonviolent Rhetoric, Ellen Gorsevski, a major modern voice of the topic of nonviolent rhetoric, argues that it is better to take a slower road to healing than to use violence to accomplish one’s goal. This is considered one of the staple characteristics of nonviolent rhetoric. While nonviolent rhetoric definitely has a place in the political sphere, one of nonviolent rhetoric’s greatest strengths is in daily life when opposing opinions having a reasonable conversation for the sake of civility. In this space, nonviolent rhetoric can establish roots for long-term societal change while avoiding the many issues critics have found in the theory.

Despite all the seeming positives of the theory, nonviolent rhetoric, like all theories, has earned its fair share of criticism. Many who oppose nonviolent rhetoric do so with the belief that it is not nearly as effective as its advocates claim and is far too utopian for reality. One of the great concerns is that in the pursuit of nonviolence, people may take a passive role while atrocities happen. While stories like Gandhi ended in favor of nonviolent rhetoric, critics will quickly point to a case like the Holocaust and question how many more people would have suffered and died had the Allies’ main strategy been nonviolent rhetoric. Even Gorsevski acknowledges that the peace she advocates for could be seen as allowing heinous acts to go unpunished. Another major criticism of nonviolent rhetoric is that it is often portrayed as a “fix” to all of society’s issues and disagreements. As one with a relatively positive outlook on nonviolent rhetoric, Sarah Dempsey admitted that the list of claims made for nonviolent rhetoric is well beyond reasonable and likely contributes to the “utopian” view of the theory. Realistically, nonviolent rhetoric has a place to be studied in rhetoric as well as a place in global, political, and social change; however, it is not a “fix all” solution.

Sources

- Dempsey, Sarah E. “Peaceful Persuasion: The Geopolitics of Nonviolent Rhetoric (Review).” Philosophy and Rhetoric, vol. 38, no. 1, 2005, pp. 89–92.

- Gorsevski, Ellen W. “Conclusion: Toward a Theory of Nonviolent Rhetoric” and “Appendix 1: Rhetoric and Nonviolence.” Peaceful Persuasion: The Geopolitics of Nonviolent Rhetoric. State University of New York Press, 2004.

- Pt’chang. “A Collection of Nonviolence Quotes.” The Commons, n.d.