6 Cultures of Colonial North America, Part I: The Darker Side of Puritanism

Colonial Cultures

Jim Ross-Nazzal, PhD and Students

“The sermons of the seventeenth century were the very essence of America.” -Perry Miller on orthodoxy in America –The New England Mind

Assertion of Liberty of Conscience by the Independents of the Westminster Assembly of Divines, 1644

PILGRIMS OR PURITANS?

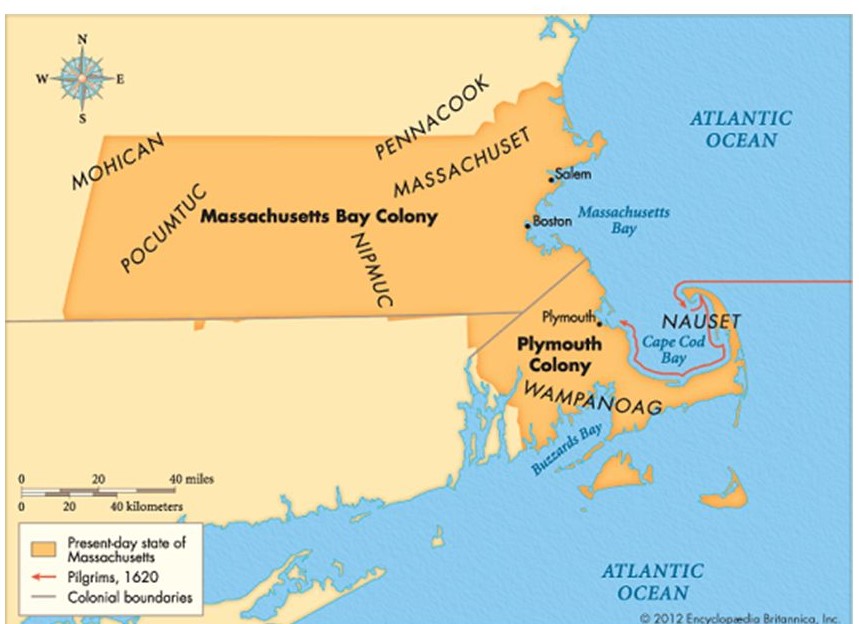

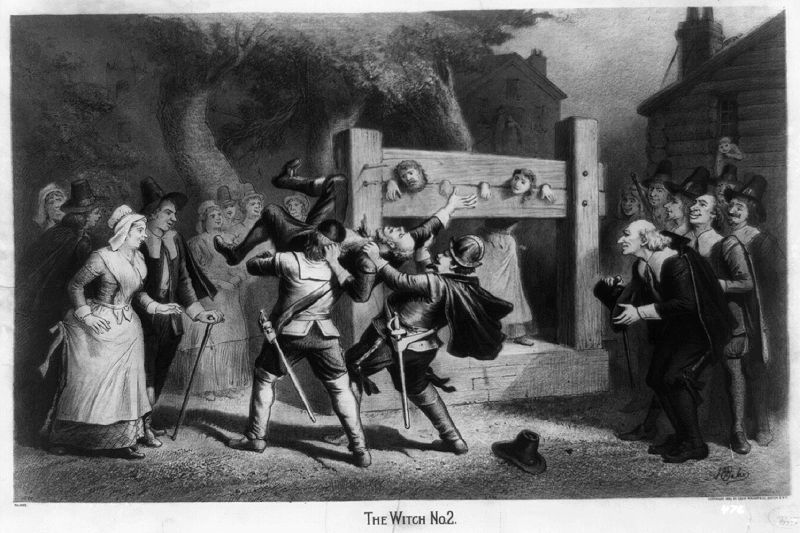

Just an oh so brief refresher of who was who so you do not confuse them at your next dinner party or cocktail event. First, Pilgrims settled Plymouth in 1620. Many arrived aboard the Mayflower. Pilgrims believed the Anglican church was corrupt to the extent that the church could not be fixed and thus they sought to completely break away from the Church of England. Puritans, on the other hand, showed up after the Pilgrims and established the Massachusetts Bay colony in the 1630s. The most famous of the ships that brought Puritans to British colonial North America was the Arbella. Puritans believed that breaking away from the Catholic church was a good first step, but that the Anglican church needed to divorce itself of all aspects of Catholicism. So, Puritans sought to reform the Church of England. The first painting is an idealized vision of the “first Thanksgiving” between Native Americans and Pilgrims, while the second is a look at one of the punishments inflicted by the Puritans upon those who broke their rules. The Puritans had a long list, some would say an entire alphabet of sins, such as “A” for adultery. Or in this case, is found to be a witch (1690s).

CALVINISM

The Pilgrims will not play a major role in the rest of the story so we will focus on the Puritans, which means we have to take a big step back to the Reformation and a fellow named John Calvin. Once upon a time, there was only one official type of Christianity. Then a German religious leader questioned the papacy’s roles in a whole bunch of ways setting off a civil war among the Germanic principalities. the war spread throughout Europe. One result was the manifestation of numerous types of Christianity, some more important to our story than others. One of the former was eventually called Calvinism established by John Calvin (he did not name the theology after himself). John Calvin preached that humans were inherently depraved but that a few would get into heaven -what he called the Elect. He preached that people could not earn or buy their way into heaven, rather God had predetermined who would get in. There was no sign, no indication who was predestined by God, but everyone was supposed to act as if they were. People had certain obligations towards each other, such as the covenant. Calvin believed that there existed a relationship between God and humanity. Humans promised to abide by God’s rules and God promised not to kill everyone prematurely and send them into Hell. Of course, breaking any of God’s rules could get that person cast into the fiery pit. So, they learned to read so they could know for themselves about God’s rules, which Calvin said were in their Christian literature. Every aspect of their lives was supposed to revolve around their Bible. If it wasn’t in the Bible, then they were not supposed to do it. So, slavery was OK but celebrating Christmas was no good.

Orthodoxy in America – The New England Mind

Puritans who came to New England were already Congregationalists (self-governing) possibly even introducing Anglicanism to the colony and answered the question “What are we doing here?” Puritan culture spread throughout the country. New England ‘Yankees” simply were adhering to certain Puritan traditions such as the work ethic and independence. The Puritan worldview was a program of “self-scrutiny to save oneself.”

Reformation

When Henry VIII in the 1530s repudiated the pope’s authority, some were already listening to Martin Luther while others adhered to the teaching of John Calvin. In 1536 Calvin published “The Institutes of the Christian Religion that taught several doctrines:

- Everyone was dammed due to original sin

- Some “elect” were chosen to be saved (predestination)

Calvin’s ideas were more popular in England than Luther’s. So, the Puritan movement grew through Henry’s heirs (except for Mary, of course.). Some were orthodox: Presbyterians (sought to slightly change church structure, Sine were reformers who wanted much change but were not willing to throw the baby out with the bathwater. And then there were Congregationalists (Separatists) who sought to do away with established church hierarchy and allow each church to govern itself by Calvinist doctrine.

Charles I (and his supporters) tried to chase the Puritans out of England. About 14,000 migrated to Massachusetts, 30,000 to the Caribbean, and 8,000 to Virginia. And many returned when civil war broke out in England.

Glorious Revolution (1688)

William and Mary were put on the English throne in a bloodless revolution (‘glorious” for protestants, not so much for England’s Catholics). Remember, aboard the Arbela, John Winthrop, Sr. gave his impassioned speech as to why his Puritan followers were in New England. His City on the Hill speech answered the question “What are we doing here?” The Puritans who settled in Massachusetts were what we would consider today to be middle class. Their ministers sought safe places to serve God and Puritans were fearful for their children’s souls in England. The Puritans focused on three things: Faith, Good Works, and the Conversion Experience.

PURITANS

Calvin’s theology spread and as ideas do, his ideas changed to meet the needs of the local social and political realities. And that brings us to the Puritans. The Puritans were Calvinists. They believed the Devil walked among them and tried to get them to break God’s rules in the hopes that God would kill them and cast them into Hell where the Devil would have more souls to mess with. Although their lives had to be biblically based, the family was seen as a covenant which meant any member of the family that broke a law could mean disaster for the whole family. The eldest male, usually dad, was the paterfamilias. He called all the shots, including “sentencing” any of his own kids to death. Better off a kid than risk losing the whole family. No premarital sex, no spousal abuse, no child abuse, and divorce was fine. Marriage was a social contract, not a religious one and so there was no stigma to getting divorced. Before getting married the parties would discuss their wants. They would write them down and sign them,. not unlike a contract. If either party broke the contract, that would be grounds for divorce. But there was tremendous anxiety: anyone could be turned against the society by the Devil, who was very real and very active in the lives of the community members, spelling instant damnation (which was especially concerning to those in town who were successful as some saw success as a possible sign that they had won the favor of God). Well, you can only live under so much pressure before snapping and we call that snapping the witchcraft craze of the 18th century or, the dark side of Puritanism. In a nutshell:

Humans are completely depraved.

Only the elect will be saved.

Election was totally unconditional upon action.

If you enjoyed the grace of God, you had many demanding and exacting obligations to pay back to the community.

The ‘true saints’ would persevere (the saints could be identified as economically successful who had great revelation of God).

God and humans had a covenant thus humans had to be careful who lived in their community. Roger Williams, for example, was expelled, also Anne Hutchinson, fearing their actions could incur God’s wrath upon the community.

SOCIAL LIFE OF PURITANS

They were far more literate than other colonists because they needed to read the bible to determine God’s rules and regulations without an intermediary.

They migrated as families (as opposed to single men who migrated to Virginia).

Climate and geography in New England discouraged slavery, but the Puritans were not against slavery.

They were conservative: maintain old ways; new ideas and innovation were bad. Some refer to this as cultural anxiety, which resulted in New England is almost frozen in time politically, socially, and economically.

The family was a covenanted association; they agreed to certain obligations to each other as well as the family to God. The community had a stake in the health of the family unit (the core of Puritanism in the colonies). Thus, the community was a bunch of busybodies. At one time, there was even a government agency established to monitor families such as ensuring that children were being treated well and that people were not living alone (the Devil could better influence people living outside of traditional family units). Sin and inequity were the companions of the solitary life.

The father was the head of the family (the paterfamilias if you would) and sons over the age of 16 could be put to death for not listening to their fathers. Marriage was not a religious practice but a civil contract. Thus Puritans allowed divorce because if either part broke their marriage contract divorce would be sought by the offended party and allowed by the community. Married women could own property and were protected against spousal abuse. Marriage should be a love match and the marriage contract was hammered out through the act of bundling. Both parties would be punished for adultery (both wore the “scarlet letter”) and premarital sex was prohibited.

WITCHES

The Puritans have been under a lot of pressure ever since John Winthrop Sr. gave his Modell of Christian Charity speech aboard the Arbella, suggesting that if they do not build the greatest city of all times, God will not be pleased. So that, and their belief in the Devil and the paterfamilias, resulted in the creation of a community of busybodies. But over time those Bible-based rules went to the wayside, church attendance dropped, women started to lie alone (that was a BIG no-no) and were not transferring their property to the eldest male in their families, and other societal rules or obligations.

In John Winthrop’s City on the Hill Speech, he convinced his followers that the Devil walked among them. He could appear in any form and he tried to get you to do his bidding to affect your status before God. The Devil likes to particularly target those who he belied were predetermined to go to heaven. This community of busybodies watched each other for signs that their neighbors were being controlled by the Devil, believing it was their Christian duty to fetter out evil in society and that evil was all around them. People can only live under so much anxiety before they crack and that cracking is known as the witchcraft craze.

Women were largely the target population and Catholics and Anglicans jumped on the bandwagon, thus spreading the fettering out of withes throughout the British colonies in the seventeenth century.

Although Salem is the most commonly known witch town, the witch craze extended beyond Salem, such as in Connecticut.[1]

Alse Young, also known as Achsah or Alice, was the first person in Windsor, Connecticut to be executed for witchcraft. She was hanged at Meeting House Square in Hartford which is now the Old State House. Young’s life details, her trial, and the consequences of her accusations are unknown. On May 26, 1647, Matthew Grant confirms the execution in his diary when he wrote that Alse Young had been executed.[2] Another case happened in 1648 with a woman named Mary Johnson, this was the first recorded confession of witchcraft in Connecticut. In 1646, Johnson was accused of theft, under the pressure of the minister and after the extended whipping, she confessed to being guilty of witchcraft. She described her crimes, including using the Devil to help her with her household chores with this she was sentenced to death.

Though the overwhelming majority of these accused of witchcraft were women, two men in Connecticut also hanged as witches: John Carrington and Nathaniel Greensmith.[3] John Carrington died along with his wife, Joan in 1651, they were executed for having entertained familiarity with Satan, the great enemy of God and mankind, and by Satan’s help, having done works above the course of human Powers.[4] Nathaniel Greensmith was executed with his wife Rebecca during a local outbreak in 1662-63 after she confessed.[5] Rebecca Greensmith claimed that she met up with the Devil and that her husband that he met strange creatures in the forest. Nathaniel Greensmith was sentenced to death for possessing supernatural strength, and for not having the fear of God before his eyes and with Satan’s help acted way beyond human abilities.[6]

In 1662, Connecticut’s Governor John Winthrop Jr, established more objective criteria for the witch trial, requiring a minimum of two witnesses for every alleged act of witchcraft. In late March eight-year-old, Elizabeth’s parents were grieving over her body in their home at Hartford. Elizabeth was well the past few days before when she had returned home with a neighbor, Goodwife Ayres. Her parents, John and Bethia Kelly, saw the hand of the devil at work, they were convinced that their daughter had been fatally possessed by Ayres. They testified that their daughter was ill the night she returned home with Ayres and that she claimed that Ayers was upon her and chokes her.[7]

According to some of my students, Paula Aguirre, Enrique Arana, Camila Arajuo, and Isabel Caballero, women were indeed the target.[8]

The people who were suspected in colonial New England varied from sex, age, marital status, or even just relations to someone who was being tried for showing signs of being a witch. Women were the ones mostly accused of practicing witchcraft on their neighbors or the neighbors’ animals. Witches were also characterized by their age, women over the age of 40 were more likely considered witches than if they were younger than 40, “Woman under forty were, in fact, unlikely witches in puritan society.”[9] This is because women under forty were thought to still be able to get pregnant and not having much time to do witchcraft since they had a responsibility to take care of their children.[10] Elizabeth Morse was found guilty and was punished. After spending almost, a year in prison, and after her husband had sent two petitions to the Boston magistrates, Morse was allowed to return home.[11] Women who were not married or widowed ran the most dangerous because if they were not married, they did not have a husband or a son to protect them of suspicions and if they were widowed they had someone that protected them as long as the husband or son was alive. Not only their marital status was a factor, but also in the accused women’s eco-social status and how she inherited her position.

Witches in the villages and towns of late 16th and early 17th England tended to be very poor. They were not usually the poorest of their communities, more like “moderately” poor. Some common factors that were used to find these “witches” would include property they owned, wealth, occupation, and political offices held. There was the stereotype of a witch being so poor that she would have to beg for her life. But in New England, there was evidence that women from every social class were at danger of being accused of being a witch. For instance, wives, daughters, and widows of “middling” farmers, artisans, and mariners were regularly accused. Now when it came down to the prosecution of these women, social class did have some sort of play in whether they ended up being hung. Unless they were single, or widowed, accused “witches” from wealthy families could be confident that the accusations would be ignored by the authorities or deflected by their male presence through suits for slander against their accusers. Many were able to escape prosecution through their husband’s influence.

By the late 1640’s New Englanders grasped on a witchcraft belief system as essential to social status. Throughout the 17th century, Puritans’ symbols, myths, and rituals believed that women posed dangers to human society. This is supported by Heinrich Institoris and Jakob Sprenger, who wrote, Malleus Maleficarum in (1486) (Ibid p.155). Which states women who interfere using herbs or other means to prevent conceptions are considered witches.[12] Puritan women were pressed on forming ideology, beliefs in which way serve them better in old hierarchies. Priest’s emphasized the importance of marriage, family, and the status of women’s relation. Moreover, Puritans were taught to complete God’s Divine as shown in the Bible. In other words, the “laws of god.”[13] For instance, it was most important to install good morals and values, pray daily and be the eye of the house. This shows a symbol to the family based on hierarchy.

Why the 17th Century?

There was an economic and gender aspect of witchcraft due to changes in private property traditions in New England in the 17th century. In Puritan New England, only men could transfer property although women could own property. Property laws were largely based on English jurisprudence, such as only men could inherit property. 75% of the accused witches in Salem, Massachusetts were women.

But due to social constraints, women had been inheriting land for some time thus establishing a tradition that flew in the face of British law. And for the most part, Puritan societies ignored that aspect of English common law, until the early part of the 17th century. So it is possible that the community tried to end this tradition and strictly adhered to British law on inheritance at a time of general economic downturn (somebody gets blamed whenever the economy gets sour).

He accused in Salem were predominately poor who owned small parcels of land. Some Puritans saw poor people as possible disruptors to Puritan communities and some Puritan communities banned poor people from residing in town (the strolling poor). But poverty does not fully answer the question because per British common law, women could inherit only one-third of the property but she could not control that inheritance. Rather the next male heir (a son for example) would decide what would be done with the land and when unmarried women (daughters) inherited land the closest make family member would hold the land in trust (femme couvere) until she got married (at which point control of the land passed to her husband). But in the early 17th century these rules were not being followed and so it is possible that the community leaders (older men) needed to maintain control, to conserve the old ways by better controlling women, and that control became being accused of being a witch.

So some men, but mainly women were concluded to be witches and properly killed such as Katherine Harrison in 1669 (not Salem) and Susana Martin in 1692 (Salem). Harrison was a widow, a landowner, and lived alone. She lived an uneventful life until her husband died leaving his good farmlands to her, elevating her wealth and thus status in Wethersfield, Connecticut. She refused to sell or transfer the land and so she must have been a witch! She was found guilty of witchcraft and sentenced to death. Her conviction will be overturned when she transferred her land to a male relative and left town. Martin tried to (and should have according to English common law) inherited part of her father’s estate but Martin’s husband had died so her father’s estate went to Martin’s half-sister. Trying to gain control of the property while living alone by someone who had a history of being accused of being a witch (yes, 1692 was not Martin’s first run-in with the law), Susana Martin was charged with being a witch. This time the charges stuck and Martin was put to death, along with a few other witches.

Now, to make things more interesting, most, but not all, of the accusers, lived in the west part of Salem and most of the defendants (and subsequent witches) lived in the east part of Salem. So, first, there is a gender aspect: women were behaving badly and so there was a response. Second, there was an economic aspect in which the accused were typically more well off than the accusers. And, the accused were typically older and lived in the older part of Salem (east) while the accusers were younger who lived in the west part of Salem. You see, those in the west part of Salem wanted to break away and form a new town but the established (more wealthy) part of Salem would have nothing to do with that, otherwise cutting their tax base off. Finally, there is a religious aspect because the accusers tended to be followers of a new kind of religious philosophy while the accused tended to be Puritans and Anglicans.

Possible Answers

Over 90% of those accused of witchcraft were female so some of this might be about control. Changes in the community resulted in women marrying later, or not at all. Those women were considered of questionable value and thus were watched more intensely than any other group in Salem. Expecting the Devil to walk among them eventually resulted in the watchers (the accusers) cracking.

The accusers tended to live in the west part of Salem while the accused tended to live in the east part of Salem. The west part was newer and wanted to break away from the city to form their own town while those in the eastern half of Salem needed community unity for taxation purposes and thus refused to allow their town to be cut in half. The accusers tended to be the New Lights while the accused tended to be the Old Lights (see the First Great Awakening, a reaction to the Enlightenment).

All of these arguments dove-tail nicely to better answer the question of how and why.

As a result of Salem (and the other witchcraft crazy towns) will be the rise of the idea of “innocent until proven guilty.”

Other students of mine investigated the witch craze outside of Salem. For example, Alejandra Cantu, Sarea Crouch, Devin Dembley, Luis Gonzalez, Rory Harris, and Thomas Hudson looked at witches in colonial Virginia and their research showed quite a different experience than Salem.[14]

The only case that resulted in death in Virginia in the case of Katherine Grady. She was aboard a ship when a horrible storm met them at sea. Her fellow passengers managed to convince Captain Bennett that she was the witch who caused it. He decided to try and end the storm by hanging Grady. There is no evidence as to whether the storm stopped after Grady was executed. The ship landed in Virginia and Captain Bennett was cleared of any wrongdoing. There are no records of the court’s findings. The only reason this case ended up in Virginia’s files is that that was the Captain’s destination.[15] So while this makes for the only death in Virginian history when it comes to witchcraft, death was not given through Virginia courts.

William Harding’s case is one of only two cases that resulted in a conviction during the witch craze in Colonial Virginia.[16] Being found guilty of sorcery, Harding was to be struck ten times publicly and then given two months to depart from the county – but not before paying all the costs of his own trial.[17] This case shows how Virginia carried out the law within its own colony. It did not follow English law word for word as sorcery, under the King James I statute, was considered a first-degree felony which punishment was to be death by hanging.[18]

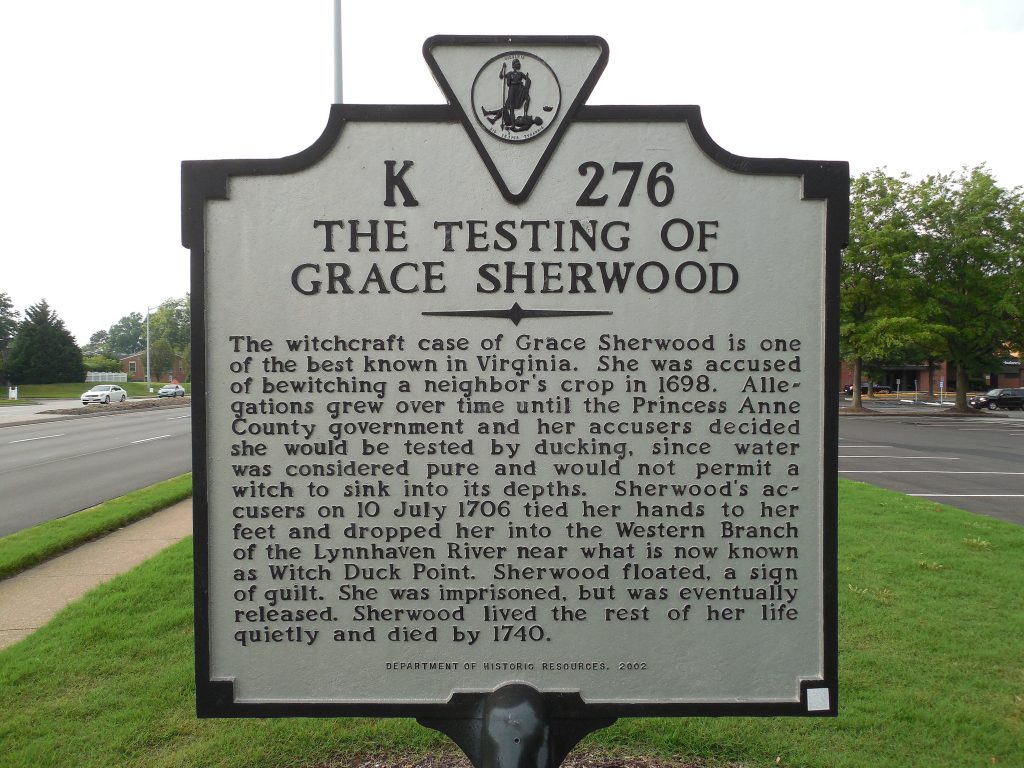

The only other conviction in Virginia was Grace Sherwood. Her case is the most famous case in Princess Anne County, Virginia since it is the only case that underwent the most scrutiny and is the only case in which multiple tests are performed. In 1698 began the legal troubles for Sherwood, she took her neighbors, the Gisburnes and the Barnes, to court for slandering her name. They had begun spreading rumors of Sherwood being a witch. The cause for which the rumors began is unknown, but the Giburnes claimed she bewitched their animals and crops and Mrs. Barnes claims Mrs. Sherwood turned into a cat right before her and went out through the keyhole of the door.[19] The courts ruled against the Sherwood’s and declared that they must pay the court for the transportation of his nine witnesses. After the death of Mrs. Sherwood’s husband, the hostility between her and her neighbors resumed and even got physical with one of her neighbors, Elizabeth Hill, causing Mrs. Sherwood to claim she was “assaulted, bruised, maimed and barbarously beaten”. The details of the altercation are unknown. Sherwood pressed charges of trespassing and assault.[20] She won the case, only getting a fraction of what she asked for in damages, and the Hill’s decided to prove her witchcraft in return. They claimed Mrs. Sherwood had performed witchcraft on Mrs. Hill and asked the court to get involved and investigate. The court summoned a jury of women to inspect Sherwood for a witch’s mark.[21] Another name used was devil’s mark. These marks were considered to be numb and unable to bleed. They were also thought to be in private areas such as armpits or genitals.[22] The searchers were of the same sex as the accused and in this case, the court demanded the women who were “ancient and knowing women” to ensure the women knew what they were searching for.[23] The accused was to be blindfolded and then pricked with a pin.[24] If no feeling was had in the mark then the searchers would conclude that the mark was supernatural.[25]

The old women found that several devil marks were indeed present on Sherwood’s body.[26] The court tried to summon another group of women to perform another test but was unable to assemble the women. With this being the case the court decided to impose another test, which was trial by ducking.[27] People believed a witch would be prevented from drowning because they had “thrown off the waters of baptism.”[28] A person would be placed in a bag with holes or inside a bed sheet with ropes tied around their waist. If the person started to drown then they were declared innocent; floating proved guilt.[29] Sherwood was bound hands to feet and lowered into the body of water and she stayed afloat.[30]

There are no records as to what actually happened to Sherwood, but what is known is she survived whatever it is she went through and grew to be roughly eighty years old.[31] With this being Virginia’s most famous case and despite all the evidence mounted against her, she was not murdered. This demonstrates how Virginia, by taking investigations seriously and not killing any person accused of being a witch, was lenient with suspected, or even what they believed to be guilty, witches.

Virginian courts followed English laws, but also dictated how they interpreted those laws especially when it came to punishments due to people such as Reginald Scot, who worked as a justice of the peace and member of Parliament, and John Webster, who wrote literature claiming not all bad luck should be blamed on witchcraft, who began to voice those investigations should be thorough considering the outcome of a guilty verdict could mean death.[32]

Colonial Virginians were also hesitant to kill due to their religion, Anglicanism. The settlers in Virginia took their religion seriously as they believed a trait of being an English person was to be an Anglican and remain part of the Church of England.[33] Anglicans rejected Calvinism, which stated that only a select few would be accepted to heaven and the rest could never earn salvation. Earning salvation and enlightenment by reason were factors that led to leniency in the Virginian courts.[34] Also, maybe due to England being across the ocean, the Virginian justices felt less pressure to follow the rules since there was no one from England there to enforce English laws and therefore Anglicans refused to kill any valuable women. During this time women were more valuable than any commodity due to men rapidly dying of illness, specifically malaria. There are only roughly twenty cases in Virginian court records and only one resulted in death.

Women & Families in Colonial America[35]

Early life in the American colonies was hard—everyone had to pitch in to produce the necessities of life. There was little room for slackers; as John Smith decreed in the Virginia colony, “He who does not work, will not eat.” Because men outnumbered women by a significant margin in the early southern colonies, life there, especially family life, was relatively unstable. But the general premise that all colonials had to work to ensure survival meant that everyone, male and female, had to do one’s job. The work required to sustain a family in the rather bleak environments of the early colonies was demanding for all.

While the women had to sew, cook, take care of domestic animals, make many of the necessities used in the household such as soap, candles, clothing, and other necessities, the men were busy building, plowing, repairing tools, harvesting crops, hunting, fishing, and protecting the family from whatever threat might come, from wild animals to Indians. It was true that the colonists brought with them traditional attitudes about the proper status and roles of women. Women were considered to be the “weaker vessels,” not as strong physically or mentally as men and less emotionally stable. Legally they could neither vote, hold public office, nor participate in legal matters on their own behalf, and opportunities for them outside the home were frequently limited. Women were expected to defer to their husbands and be obedient to them without question. Husbands, in turn, were expected to protect their wives against all threats, even at the cost of their own lives if necessary.

It is clear that separation of labor existed in the New World—women did traditional work generally associated with females. But because labor was so valuable in colonial America, many women were able to demonstrate their worth by pursuing positions such as midwives, merchants, printers, and even doctors. In addition, because the survival of the family depended upon the contribution of every family member—including children, once they were old enough to work—women often had to step into their husband’s roles in case of incapacitation from injury or illness. Women were commonly able to contribute to the labor involved in farming by attending the births of livestock, driving plow horses, and so on. Because the family was the main unit of society, and was especially strong in New England, the wife’s position within the family, while subordinate to that of her husband, nevertheless meant that through her husband she could participate in the public life of the colony. It was assumed, for example, that when a man cast a vote in any sort of election, the vote was cast on behalf of his family. If the husband were indisposed at the time of the election, wives were generally allowed to cast the family vote in his place.

Women were in short supply in the colonies, as indeed was all labor, so they tended to be more highly valued than in Europe. The wife was an essential component of the nuclear family, and without a strong and productive wife, a family would struggle to survive. If a woman became a widow, for example, suitors would appear with almost unseemly haste to bid for the services of the woman through marriage. (In the Virginia colony it was bantered about that when a single man showed up with flowers at the funeral of a husband, he was more likely to be courting than mourning or offering condolences.)

Religion in Puritan New England followed congregational traditions, meaning that the church hierarchy was not as highly developed as in the Anglican and Catholic faiths. New England women tended to join the church in greater numbers than men, a phenomenon known as the “feminization” of religion, although it is not clear how that came about. In general, colonial women fared well for the times in which they lived. In any case, the lead in the family practice of religion in New England was often taken by the wife. It was the mother who brought up the children to be good Christians and the mother who often taught them to read so that they could study the Bible. Because both men and women were required to live according to God’s law, both boys and girls were taught to read the Bible.

The feminization of religion in New England set an important precedent for what later became known as “Republican motherhood” during the Revolutionary period. Because mothers were responsible for the raising of good Christian children, as the religious intensity of Puritan New England tapered off, it was the mother who was later expected to raise children who were ethically sound, and who would become good citizens. When the American Revolution shifted responsibility for the moral condition of the state from the monarch to “we, the people,” the raising of children to become good citizens became a political contribution of good “republican” mothers.

Despite the traditional restrictions on colonial women, many examples can be found indicating that women were often granted legal and economic rights and were allowed to pursue businesses; many women were more than mere housewives, and their responsibilities were important and often highly valued in colonial society. They appeared in court, conducted business, and participated in public affairs from time to time, circumstances warranting. Although women in colonial America could by no means be considered to have been held “equal” to men, they were as a rule probably as well off as women anywhere in the world, and in general probably even better off.

Although women in colonial America were subject to the same prejudices that had existed in Western culture for centuries, the nature of life in America brought about more favorable circumstances for women. Because everybody had to work, and because labor was viable in America, the presence of women was seen as a blessing or leased a necessity. Men worked hard, and the women were responsible for the raising of the children. The children, in turn, were expected to be productive members of the family and as soon as they were old enough they began performing various chores and tasks around the household and farm to help ease the burdens of their hard-working parents. Girls learned the chores that were traditionally a woman’s lot, while boys learned how to assist their fathers in the fields and workshops. Family discipline was of necessity often strict; children who are slackers constituted a burden rather than an aid to their families. They expected to lead lives similar to those of their parents, but in a land that offered a modicum of opportunity for prosperity, such expectations were reasonable.

I wish to thank my Fall 2019 students Paula Aguirre, Enrique Arana, Camila Arajuo, Isabel Caballero, Alejandra Cantu, Sarea Crouch, Devin Dembley, Luis Gonzalez, Rory Harris, and Thomas Hudson for their interest in the intersection of women and culture. Their participation made this chapter more full and rich.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies. Please point them out to me so that I may make this chapter better. I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- This section was researched and written by Jessica Figueroa, Spring 2020. ↵

- Andy Piascik, Witchcraft in Connecticut, https://connecticuthistory.org/witchcraft-in-connecticut/, (Last accessed March 12, 2020) ↵

- Carol F. Karlsen, The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England pg 300. ↵

- Juliet Haines Mofford, Devil Made Me Do It!: Crime and Punishment in Early New England pg 109-110. ↵

- Elizabeth Reis, Spellbound: Women and Witchcraft in America pg 49. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Walter W. Woodward, New England’s Other Witch-Hunt: The Hartford Witch-Hunt of the 1660s and Changing Patterns in Witchcraft Prosecution, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25163616?seq=3#metadata_info_tab_contents, (Last accessed March 12, 2020) ↵

- These students wrote an essay on witchcraft using the book The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: The Witch in Seventeenth-Century New England. They wrote their essay in the Fall of 2019. ↵

- Karlsen, C. F. (1980). The devil in the shape of a woman: the witch in seventeenth-century New England page 64). ↵

- Ibid p. 71 ↵

- Ibid p.67 ↵

- Ibid p.157 ↵

- Ibid p.162 ↵

- These students wrote this essay primarily using the monograph Witchcraft in Colonial Virginia. ↵

- Carson O. Hudson Jr., Witchcraft in Colonial Virginia (South Carolina: The History Press, 2019), 81 ↵

- Ibid, 82. ↵

- Ibid, 81. ↵

- Ibid, 46. ↵

- Ibid, 90. ↵

- Ibid, 91. ↵

- Ibid, 92. ↵

- Ibid, 18. ↵

- Ibid, 20. ↵

- Ibid, 18. ↵

- Ibid, 19. ↵

- Ibid, 93. ↵

- Ibid, 94. ↵

- Ibid, 27. ↵

- Ibid, 28. ↵

- Ibid, 95. ↵

- Ibid, 97. ↵

- Ibid, 57 and 66. ↵

- Catherine Locks, Sarah Mergel, Pamela Roseman, Tamara Spike, History in the Making: A History of the People of the United States of America to 1877 (Georgia: UNG Pressbooks, 2013), 140. ↵

- Christine Leigh Heyrman, “Church of England in Early America,” Teacher Serve. ↵

- This entire section is from http://sageamericanhistory.net/colonial/topics/coloniallife.html ↵