26 The Great War Part II

“With all of the Fake News coming out of NBC and the Networks, at what point is it appropriate to challenge their License? Bad for country!” -Donald Trump[1]

Curbing Dissent at Home

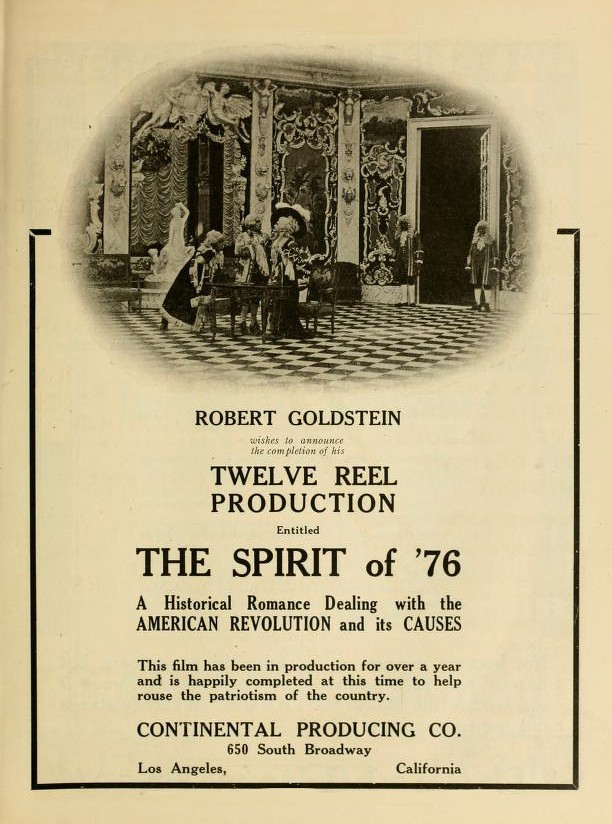

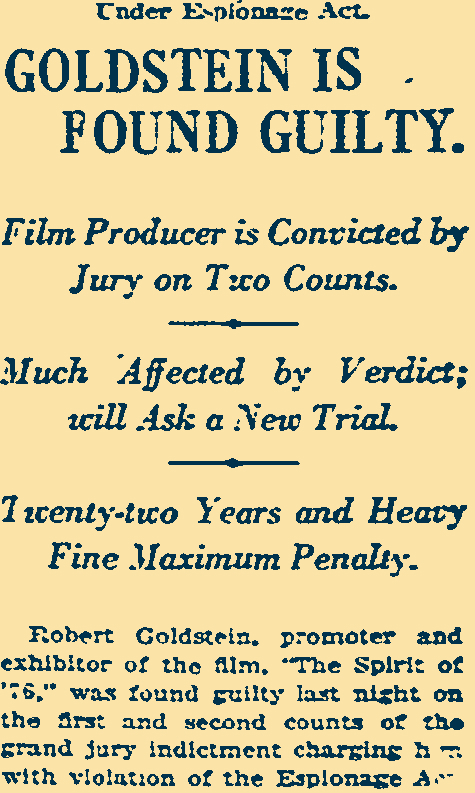

The Spirit of ’76 was envisioned as another patriotic movie. Set during the American Revolution, the idea behind the movie was that the colonists were unprepared to battle let alone win in a war against the largest, best military in the world. In the end, Americans were victorious and thus the message of the movie was that we were unprepared before yet we did what was necessary to win and we are unprepared now yet we will again do what is necessary to beat down the proud. The director of the movie, Robert Goldstein (a Jewish American of German descent) portrayed the British as not only the enemy (which they were) but unfortunately for him also decided to portray British acts of brutality (which there were many). It was an ill-fated decision for Goldstein because when the movie came out (1917) the British were our allies and thus portraying our allies in unfavorable light brought not only ridicule upon Goldstein, but also his arrest and imprisonment. He was arrested for and found guilt of breaking the 1918 Sedition Act by showing the two war-time allies (Great Britain and the US) fighting against one another. Wilson will cut short his ten-year sentence with a presidential pardon after serving 18 months in prison.

One of the first victims of nearly every US war is the First Amendment. Luckily, it is a resilient piece of work and thus will bounce back. The Alien Act (1917) and the Sedition Act temporarily trumped American’s rights to religious freedom, speak freely, publish freely, or to freely petition the government. The Espionage Act made it a crime to pass information with the intent of harming the success of American armed forces. Eugene Debs (labor leader, Socialist, perennial presidential candidate) was arrested for making an anti-American speech. He was tried and found guilty under the Espionage Act, even thought the Act did not specifically prohibit speaking against the government. Thus, to shore up the Espionage Act, Congress passed the Sedition Act which expressly prohibited speaking, writing, publishing or allowing to speak, write or publish anything against the federal government, the US war effort, or its allies or “incite insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty, in the military or naval forces of the United States” to include interfering with recruitment operations.

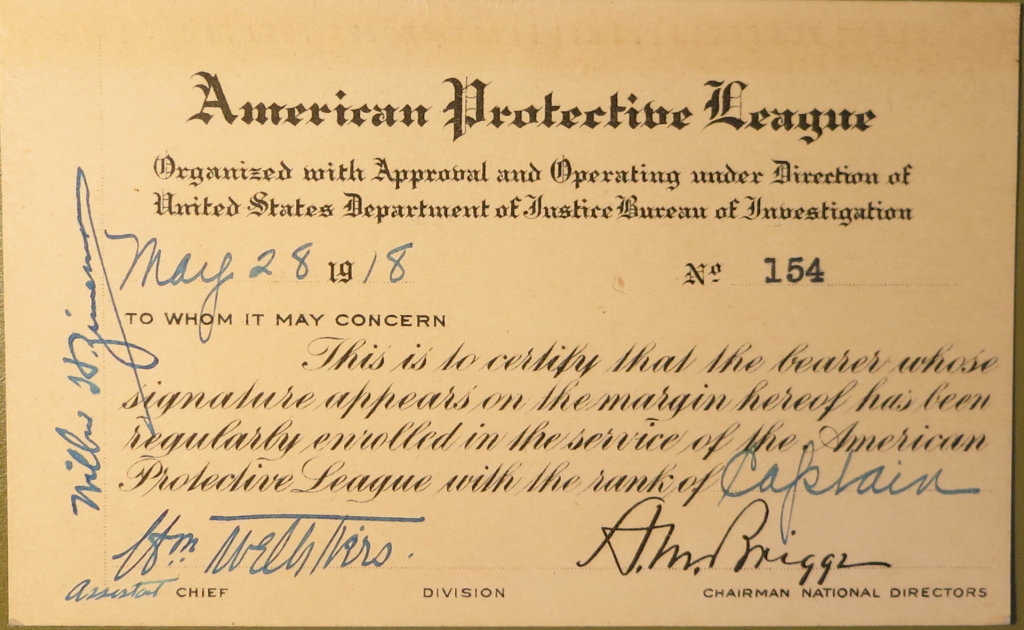

The Attorney General, Thomas Gregory, instructed the Postmaster General, Albert Burleson, to censure and if necessary discontinue delivering any anti-American or pro-German mail (letters, magazines, and newspapers). Gregory supported the work of the American Protective League’s (APL). The APL curbed dissent at home by compelling German-Americans to sign a pledge of allegiance. The APL also conducted extra-governmental surveillance on pro-German activities and organizations (such as unions).

Gregory and Burleson targeted thousands of suspected enemies of the state to include such prominent Socialists as Eugene Debs, Mary Harris Jones (aka “Mother Jones), Emma Goldstein and Max Eastman because of their use of the US mail to distribute what Gregory and Burleson considered to be un-American literature. Besides Socialist newspapers such as The Call, Burleson prohibited the delivery of what he considered to be anti-British publications such as The Irish World and The Gaelic American.

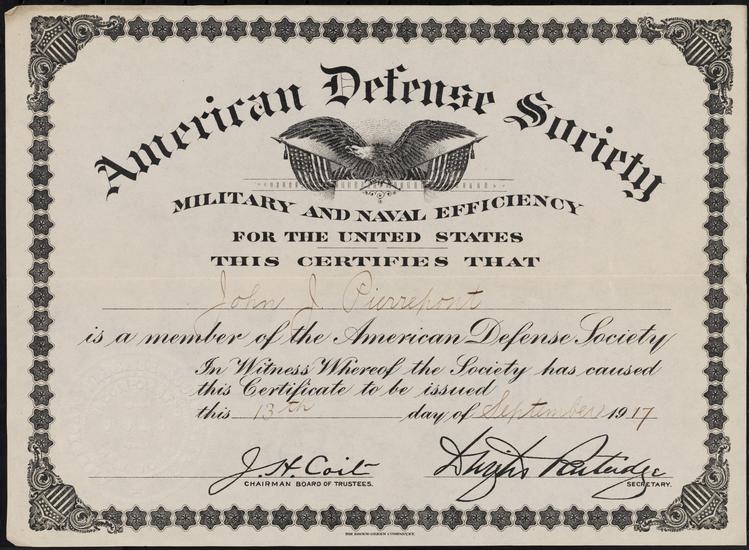

Anti-German fervor during the Great War resulted in the renaming of German (or German-sounding) food. Sauerkraut became liberty cabbage. Frankfurters became hot dogs, and Salisbury Steak turned into meat loaf. The American Defense Society (an organization established to protect the US in the wake of the Lusitania sinking), with President Teddy Roosevelt as its honorary president, petitioned Congress to prohibit the study of German in all public schools. They also called for compulsory military training for all men between 18 and 21, and for “greater activity in the internment of enemy aliens and sympathizers.”

Extralegal organizations, such as the Wisconsin Loyalty League sought to control their relatively large German population as well as their own elected officials who questioned the war. For example, Wisconsin Senator Bob LaFollette, a Progressive Democrat, decried American entry into the war on the basis that the US had indeed been breaking international law by shipping explosives on civilian ships (such as the Lusitania) and thus going to war to protect neutral rights was absurd. Ex-president Teddy Roosevelt called LaFollette a “shadow Hun” and “the most sinister enemy of democracy in the United States.”

Wisconsin voters from the industrial southeast part of the state seemed to side with LaFollette because the voters of Milwaukee, the state’s largest city, elected a string of Socialist mayors to include Emil Seidel (1910-1916) and the longest sitting Socialist politician on US history, Daniel Hoan (1916-1940). They also sent this nation’s first Socialist congressman to the US House of Representatives: Victor Berger (1910-1912, 1918-1920, 1922-1928). Wisconsin voters seemed to be out of step with the majority of American leader such as Gregory. “May God have mercy on [dissenters],” said the US Attorney General, “for they need expect none from an outraged people and an avenging government.”

In early September, Congress passed a bill that required all German-language newspapers published in the United States to print an English translation “of any comment respecting the Government of the United States, or of any nation with which Germany is at war, its policies, international relations, the state or conduct of the war, or any matter relating thereto,” according to Senator William King (D-Utah) in his attempt to rid this country of newspapers that spread, as he called it, “the blackest treason.”

In 1919, the US Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Espionage and Sedition Acts. Charles Schenck was one of the leaders of the Socialist Party of America and as such oversaw the distribution of pamphlets, to include tens of thousands sent to men of draft age, urging them to not serve if drafted arguing that the draft violated the Thirteenth Amendment. In a unanimous decision, the thrice-wounded Civil War veteran Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr, stated “[w]hen a nation is at war many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.” In other words, the needs of the state supersede the needs of the individual and thus dissent was codified.

Armistice did not end anti-German hysteria. While most Americans were celebrating the end of the war, 38 “dangerous enemy aliens” were rounded up in New York and were sent to Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia for undetermined lengths of time, to include three officers of the Bayer Company (a German pharmaceutical firm known for its aspirin that opened a branch office in the United States in the early twentieth century).

The Home Front

In 1914, Congress passed the Smith-Lever Act, which created the Cooperative Extension Service in order to develop more effective agricultural and animal husbandry classes, programs, and use in and of land grant institutions such as Washington State University, Texas Agriculture & Mining, and the University of Wisconsin. Yet the Act also mandated land grant universities to share their knowledge with non-students (hence the “Extension” part of the title).

Once the US openly joined the war, Congress worked to ensure that Americans at home and abroad had sufficient resources and thus Congress adopted the Fuel and Food Control Act in 1917. The Fuel Administration controlled the production, distribution, and price of fuels (oil, gas, and coal, for example) and was led by Dr. Harry A. Garfield –son of and witness to the assassination of President James B. Garfield in 1881. Like many of the men whom Wilson surrounded himself, Garfield was an academic serving as a professor at Princeton (when Wilson presided as the college’s president) and as the president of Williams College in Massachusetts.

Although Garfield was a Republican, Wilson and Garfield were connected as academics as well as Progressive thinkers who believed in the transformative nature of the human spirit. According to Garfield, academia was the place were “cultivated men, earnest and seeking by all ways to advance the cause of civilization.” And thus, as Wilson’s Secretary of War Newton Baker said, “The President had unlimited confidence in Garfield.” Unlike Garfield’s colleagues on Wilson’s Cabinet and heading various war time organizations, Garfield did not seek absolute power within the organization he led nor throughout American society.

At a meeting of the Academy of Political Science, Garfield offered a justification for the Fuel Administration’s existence as well as assurances that under his watch the Fuel Administration will not nationalize the fuel industry. In his speech entitled “Task of the Fuel Administration,” the gap between the fuel needs of a country at war compared to the needs of the US in 1916 would be largely met through conservation, he argued. In an example of the government-academic cooperation that will be a characteristic of American society ever since World War II, Garfield turned to scientists and mathematicians in academia to resolve some of the issues pertaining to fuel conservation.

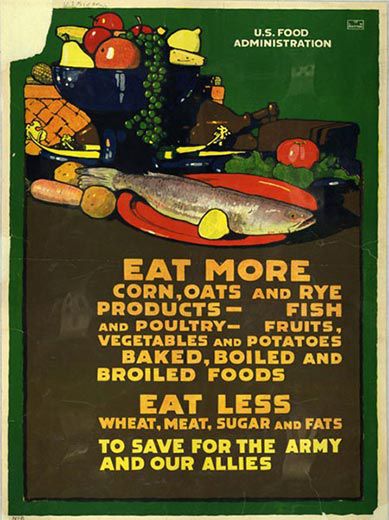

Using the authority of the 1917 Act, President Wilson issued Executive Order 2679A, creating the US Food Administration. Headed by future president Herbert Hoover, the Food Administration was tasked with assuring the supply, distribution, and conservation of food during the war, facilitating transportation of food, preventing monopolies and hoarding, and maintaining governmental power over foods by using voluntary agreements and a licensing system. In trying to get Americans to conserve what they have and to use less of what can be grown or made, Hoover promoted “Meatless Mondays” and “Wheatless Wednesdays.”

The Food Administration asked Americans to grow their own vegetables (called “Victory Gardens”) and to pledge to follow the call to preserve, consume less, and grow more in order to ensure that sufficient meat, wheat, fats, and sugars make it to the US troops and American allies. The Milwaukee Journal, the largest daily in Wisconsin, proclaimed that 100% of their citizens took the pledge to eat less and preserve more. Wisconsin had more German immigrants than any other state. Wisconsin also had an active Socialist movement and thus it was psychologically important for the owners of that newspaper to advertise a claim that was more than merely improbable. The publishers of Good Housekeeping urged its readers to support the government efforts believing that:

“its large circle of earnest, patriotic women readers will respond gladly to a call to service at home. It is a tremendous task—this one of conservation and elimination of waste. Every woman is urged to do her part. It can best be done through close cooperation with the government. Enlist now and pledge yourself to do your share.”

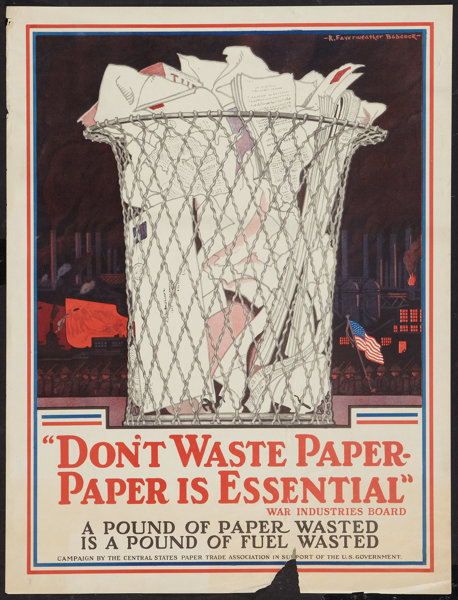

Finally, the War Industries Board (WIB), created in the mid-summer of 1917, was another federal agency tasked with ensuring that Americans at home and abroad had access to acceptably priced merchandise and equipment. The WIB was led by Bernard Baruch, a friend of Wilson’s in academia and business. A graduate of City College of New York, Baruch made his first million by his thirtieth birthday (1900) as a Wall Street trader and financier. Baruch was a major financial donor as well as unpaid adviser to the Democratic Party for most of his adult life. As part of Wilson’s “War Cabinet,” Baruch worked closely with Hoover. While Hoover’s emphasis was on agriculture, Baruch focused on American industry. The WIB was ordered into a series of divisions that oversaw all aspects of war needs from distribution of raw resources to control of prices on the finished goods to include chemical, steel, textile, rubber, and leather goods.

Secretary of Labor, William B. Wilson, created the National War Labor Board (NWLB) in 1918. While the WIB consisted of military personnel and public servants, the NWLB was composed of civilians, mainly from labor unions, industrial management, and the general public. This group was tasked with settling labor issues, disputes, and other issues that otherwise might negatively affect this country’s wartime production.

Wartime Diplomacy

Woodrow Wilson envisioned a quick war. A combination of coordination among the US and its allies in food production, equipment needs, and communications was facilitated by the various government programs and agencies that fell under the rubric of Wilson’s War Cabinet such as the War Industries Board, the Fuel Administration, and the Food Administration. International “cooperation” among the Allies was evident through the creation of the Supreme War Council. The US representative to this group was Wilson’s Army Chief of Staff, Tasker H. Bliss. Initially, the Council was tasked with coordinating allied military action. Ultimately, the Council will prove to be more effective as a space where the allies discussed diplomatic endeavors to include how to bring an end to the war, and what should be included in the peace treaty. Wilson’s outlined his goals for how the war will end as well as for how Europe (and the world) will be rebuilt in a speech he gave on January 8th, 1918.

Those ideas came from the work of academics: a group of men that Wilson called “The Inquiry.” Meeting in secret at the offices of the American Geographic Society in New York City, these scholars researched and discussed various post-war options for Europe. The Inquiry is very much the forerunner to today’s Think Tanks such as the Heritage Foundation and the Pew Research Center. “We are skimming the cream of the younger and more imaginative scholars,” declared Walter Lippmann, the 28-year-old Harvard graduate who recruited the scholars and managed the Inquiry in its formative phase. “What we are on the lookout for is genius—sheer, startling genius, and nothing else will do.”

The suggestions, ideas, and conclusions of the Inquiry culminated in fourteen particular ideas that Wilson publicly unveiled in early January of 1918 in what is called the “Fourteen Points Address.” Reminding the joint session of Congress that the US got involved in the war not only to protect American liberties at home but also to spread American liberties throughout the world, Wilson envisioned a world “made fit and safe to live in; and particularly that it be made safe for every peace-loving nation which, like our own, wishes to live its own life, determine its own institutions, be assured of justice and fair dealing by other peoples of the world as against force and selfish aggression.”

Wilson called for international trade unrestricted by law or tariffs, an end to secret treaties and military alliances, and an end to colonialism. The world would be made safe through vigilant international cooperation. As he described it in the final of his fourteen points, “A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.”

England and France (the two allies who fought the longest and sacrificed more in both material and human lives) did not great Wilson’s ideas for a new world order with open arms. For example, Arthur Balfour, the British Foreign Secretary and one-time Prime Minister, seemed to be uninterested in any sort of negotiated settlement, instead calling for Germany to provide England and France with “unconditional restoration and reparation” of all taken, plundered, and destroyed lands. Neither did the Belgian Prime Minister accept Wilson’s extensive plan. Baron Charles de Broqueville merely demanded “reparation for damages and guarantees against repetition of the aggression.” Earlier, Wilson had called for “peace without victory” which meant that the Allies did not need to crush Germany. The Inquiry and Wilson might have underestimated the Allies’ desire to punish Germany and so Wilson was out of step with his European counterparts regarding diplomatic goals.

The Peace to End All Peace

Russia had quit the war prematurely and had thus signed its own peace treaty with Germany. Known as Brest-Litovsk, Russia essentially ceded lands (such as the Ukraine, the Baltic states, Finland, the Caucasus Mountains and Poland) to Germany in exchange for the removal of German troops from Russian soil. However, six days before the Armistice, German officials repudiated the March 3rd, 1918 treaty.

With communists in charge of Russia, only England, France, Italy, and the US met to decide the fate of the Central Powers. Even though the Cold War would not begin for decades, the seeds of that twentieth-century conflict were planted at Versailles. Although the western powers wished to crush Germany, they could not leave Germany in such a state as to allow the Russian Revolution to spread west. For example, Germany was forced to give back some of Russia’s losses as a result of Brest-Litovsk and the League of Nations in turn created the Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia (important speed bumps in the mind of Soviet leaders to slow down the next German invasion) however American, British, and other Allies kept troops in Germany through the mid 1920s thus ensuring that the Communist army and its agents would not be able to move into the beaten, battered, and considerably smaller Germany.

Versailles will also acknowledge the German repudiation of Brest-Litovsk, but also does nothing to directly help Russia adjudicate, mediate, or guarantee any economic reimbursement from Germany, except to state that “[t]he Allied and Associated Powers formally reserve the rights of Russia to obtain from Germany restitution and reparation based on the principles of the present Treaty” (Part III, Section XIV, Article 116). In other words, Russia is on its own to negotiate with Germany.

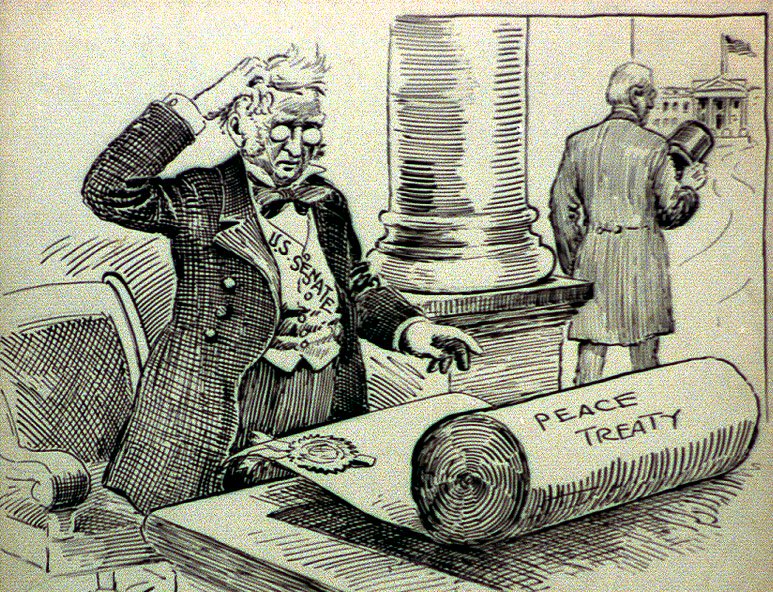

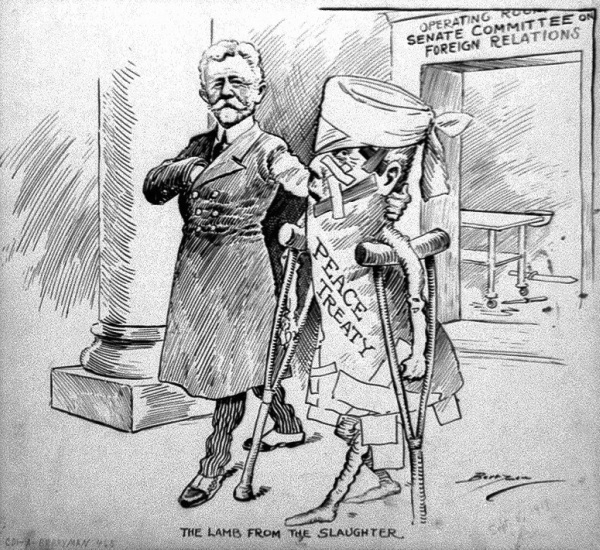

Wilson took nearly all of the members of the Inquiry, plus his closest friend and unofficial adviser, Col. Edmund House to France. Wilson also ignored leading Democratic and Republic senators and thus no one should be shocked to find out that the US Senate will never pass the treaty Wilson helped create in Versailles. The Republicans controlled the Senate, yet Wilson refused to consider adding the Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee chairman, Henry Cabot Lodge, to the American group that went to France.

Wilson’s second problem in Versailles was the Allies. France and England had no interest in discussing, analyzing or negotiating anything: they sought to carve up Germany and its colonies like a group of hunters carving up a bear after a successful hunt. With the massive destruction to property and lives in England and France, the allies were not willing to embrace Wilson’s “peace without victory” philosophy. The Allies blamed Germany for starting the war and for all damage and deaths during the war. Parts of Germany will be carved away and given to France, such as the coal-rich eastern parts of Germany (the Saar Valley). Germany will lose all of their colonies and Germany itself (or what’s left of Germany) will be an occupied nation until 1926 –the year that Germany is allowed membership into the League of Nations.

Wilson’s final problem in Versailles was his health. He had become physically exhausted in large measure because he decided to lead the US delegation. Some speculate that Wilson even suffered up to three strokes before he was elected president in 1912. Nonetheless, Wilson was determined to see his vision for a world “safe for democracy” come true and thus Wilson told a reporter who inquired into the president’s health, “I do not want to do anything foolhardy, but the League of Nations is now in its crisis, and if it fails, I hate to think what will happen to the world … I cannot put my personal safety, my health, in the balance against my duty — I must go.” Wilson embarked on a cross-country speaking tour as he attempted to whip up support for the Treaty in general and the League of Nations in particular. Wilson suffered a massive stroke in the early fall of 1919. He would not be seen in public for six months.

The Treaty of Versailles was a disaster and set the stage for World War II. Some historians look at the 1920s not as a period between world wars but rather as a lull in one great war that began in August of 1914 with a series of war declarations and ended in August of 1945 with the dropping of Fat Man and Little Boy on Japan.

Treaty Fight at Home

President Wilson’s decision to personally lead the US delegation to Versailles while also refusing to even keep senatorial leaders of his own party aware of the negotiations resulted in a contest back at home regarding foreign policy. While a fight between the Executive and Legislative branches of the federal government regarding foreign policy was not new, such a fight was also very rare. Nonetheless, ever since the Spanish-American War, culminating with the passage of the War Powers Act of 1973, US presidents and senators have been arguing over which branch of the federal government ultimately controls US foreign policy.

The treaty to end the war and to bring to a conclusion all of the issues and problems (as the victors of the war saw those issues and problems) was signed by all parties on June 28th, 1919. Known as the Treaty of Versailles, the treaty is divided into sixteen sections, containing a total of 440 articles. France gained control of some of Germany’s more productive coal fields, England seized German colonies in Africa and in Asia; France and England claimed the frontier of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East to include Palestine and Syria, and Germany was forced to disarm. The Treaty also demanded Germany to pay for all costs of the war, and approximately two thousand German politicians and military officers will be tried on a variety of crimes, mainly due to submarine warfare as the Allies viewed that as less military and more criminal in nature.

The US Senate had a difficult time getting past the first section of the Treaty, entitled “The Covenant of the League of Nations.” The tenth article of this section describes the collective nature of the League in so much that an attack against any one member will be considered an attack against all members and thus “[t]he Members of the League undertake to respect and preserve as against external aggression the territorial integrity and existing political independence of all Members of the League.” The common understanding of this clause was that if any member nation is attacked from a foreign power, then all member nations will mobilize their armed forces to aid in the defense of the attacked member state. Of course the underlying belief is that no country would dare attack any member of the League because such an attack would result in the full force of all member armed forces against the aggressor.

The Senate found Article 10 of the Covenant of the League of Nations to be exceptionally troubling because as they understood it, the US –as a member of the League – would be obligated to enter into every war that involves a foreign attack against any member nation. In other words, the US Senate’s authority under Article I, Section VIII of the US Constitution to declare war would be trumped by any tyrant, king, or madman who invaded a member state. Furthermore, in accordance with Article 16, if any member of the League attacked any other member, then all members were required to immediately end all trade and financial relations. The US went to war, in part, over the idea of neutral rights however if the US joined the League, the trade policy of the US could be determined not by the leaders of this country, but by the treaty requirements of the League of Nations.

Thirty-nine Senators openly rejected this attack on their Constitutional authority in a letter to include the Senator from Massachusetts, a leading Republican politician, and chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Henry Cabot Lodge. Lodge did not reject the whole treaty, he just held reservations on Article 10 and thus Lodge was known as a “Reservationist.” Democrats such as William Jennings Bryan supported this position.

The Republican William Borah served the people of Idaho in the US Senate from 1907 until his death in 1940. Known as the “Irreconcilables” senators such as Borah rejected the League, in any form, because of the old Washingtonian-Jeffersonian concern over entangling alliances. Borah spoke for two hours against the Treaty of Versailles in what one colleague called “one of the Senate’s oratorical masterpieces.” He began his attacks against supporting colonialism by reminding the audience of President-elect Abraham Lincoln’s advice to a friend of his in Washington, DC regarding discussions with Confederates on the issues of war: “Entertain no compromise; have none of it.”

Before the Allies completed their work in Versailles, the US had entered its second year of fighting in Russia. Russia prematurely quit the allied cause in large measure because the czar lost control of his country as a result of a revolution. By 1918 it was clear that communists had taken control of Russia and thus in 1918, the United States (along with Great Britain and other western nations) invaded Russia. By Labor Day, 1918, American troops took control of the Russian port town Vladivostok. Under the command of General William Graves, nearly 8,000 American troops protected the local railroad and supported Czech troops also fighting against the Russian communists. About 4,000 US troops fought under British command directly against communist forces in what was known as the Polar Bear Expedition. The United States actively participated in the Russian civil war until 1920.

One year and one week after the Guns of August fell silent, the US Senate voted to reject the Treaty of Versailles, US troops occupied and fought in various parts of Russia, President Wilson was recovering from his latest stroke, Americans were dying from a new illness (see below), and elements of the US Army were stationed throughout the country, such as on street corners in Omaha, Nebraska. The Treaty fight just might have been the least important thing on the minds of Americans.

Wartime Amendments

The Great War will indeed play a role in the adoption of two changes to the US Constitution. Although both changes had been looming on the cultural-political horizon since long before the Civil War, people and events during the Great War will propel this nation’s leaders to try two kinds of changes. One will be temporary and the other will be permanent.

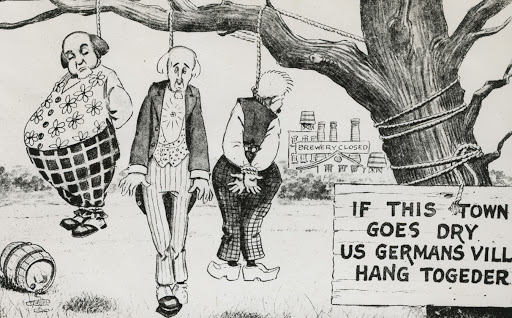

The push to end the availability of alcohol in the United States picked up steam in the years leading up to the US entry into World War I. As more and more states tried to codify the making, selling, and consumption of alcohol, some wondered if states had the power to do so and thus in 1913 Congress passed the Webb-Kenyon Act to help states enforce their prohibition laws in light of a Supreme Court decision that struck down dry states’ attempts to prohibit the importation of alcohol. In 1917, the Supreme Court ruled that no one had “a right” to alcohol, thus aligning the Judicial Branch with the Legislative Branch.

By New Years Day, 1916, eighteen states had gone “dry.” Leading the anti-prohibition charge was August Busch, president of Anheuser-Busch Brewing Association. Busch wanted to make it a crime to drink to excess, and pledged to work aggressively with the federal and state governments to address the issues of the day. He even announced that his company was developing a nearly alcohol free beer (less than one-quarter of one percent of alcohol) and was spending $3,00,000 to build a new plant in St. Louis specifically to make and distribute this new product.

Shortly after the US officially entered the war but seven months before Congress passed the Eighteenth Amendment, Dr. Irving Fischer (professor of Public Economy at Yale and adviser to Woodrow Wilson) called for either the immediate end of the war or the immediate acceptance of prohibition. The world needed bread, the member of the Council of National Defense reported. He said the US was on the verge of a “food crisis” and taking into consideration all of the food stuffs, energy, and manpower used to make alcohol, the US could instead produce 11,000,000 one-pound loaves of bread daily. “We shall be wise to adopt [Prohibition] before we have food riots on our hands” and he curbed his argument with patriotism: “The nation demands that [anti-prohibitionists] put love of country above love of whisky.”

One month before Congress adopted the Eighteenth Amendment and sent it off to the states for ratification, the Anti-Saloon League reported that making, selling, and consuming alcohol only aided the German war effort and questioned the loyalty of Americans of German descent. According to Wayne Wheeler, counsel for the League, trafficking in alcohol was how anti-American groups finance their “promotion of German ideals and German Kultur.” “We cannot serve two masters,” he said. “America must come first if we are loyal.” Thus, alcohol becomes a symbol of your allegiance during the war. One hundred and forty-four years earlier, England slapped a tax on tea and thus tea became a symbol of your allegiance. Those who consumed the taxed good supported England, while those who switched to coffee (an untaxed beverage) were considered loyal to the cause of the American colonists.

Once Congress passed the Eighteenth Amendment and sent it off to the states for ratification, the American Medical Association announced their support of Prohibition, likening alcohol to slavery and arguing that the future for the US if it continues to drink can be seen in Germany and likens that country “to a man suffering from the final stages of ‘a horrible disease, leading to insanity, with delusions of grandeur and magnificence.” Medical, social, and religious groups lined up in support of the Eighteenth Amendment.

In early January of 1919, Nebraska ratified the Eighteenth Amendment making it part of the Constitution. A small news item in the New York Times noted the passing of this nation’s oldest brewery, established in 1844. “The Pabst Brewing Company . . . passed out of existence today.” Near beer, or nearly alcohol-free beer, was produced and distributed in an early attempt to keep the brewery industry afloat. The report concluded, “Milwaukee does not take kindly to near beer.” Neither did the rest of this country.

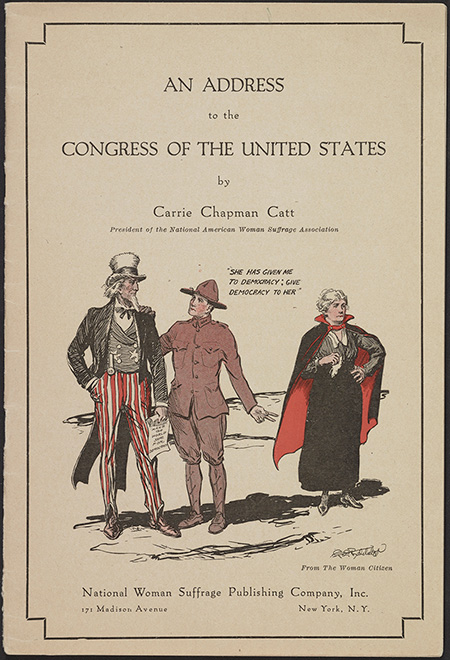

Wars and national emergencies tend to change this country –sometimes for the better and sometimes not. The adoption of Prohibition is a good example of the former, while the passage of universal suffrage is a good example of the former. If all you knew about the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment was from watching the 1976 ABC Schoolhouse Rock episode entitled “Sufferin’ Till Suffrage,” you would think that a bunch of happy, upbeat, women sporting red bell-bottom jeans, white boots, and blue t-shirts with a lone white star (note the obvious flag theme) pranced into election booths simply by singing: “Oh we were sufferin’, Until suffrage, Not a woman here could vote, No matter what age. Then the 19th Amendment struck down that restrictive rule.”

American women (and some men) had been trying to, and over time achieved varying degrees of voting rights for women. Generally speaking, women gained the right to vote in school board elections first, then municipal elections, and sometimes even in state or territory-wide campaigns. Of course, sometimes the Supreme Court removed women’s right to vote, such as in 1887 when the Court struck down an 1883 vote in the territory of Washington that granted full suffrage to women. By the Great War, women in Utah, Colorado, Washington, California, Alaska, Oregon, Arizona, Kansas, Nevada, and Montana have the same political rights as men while women in Illinois are allowed to vote only in presidential elections and white women could vote in primary elections in Arkansas. Five Midwestern states grant full suffrage to women in 1917 while Rhode Island endorsed partial voting rights. New York became the first eastern state to provide its female citizens with the same electoral rights as their male citizens. Yet, President Wilson was unable or unwilling to ride the wave of woman suffrage (not the singular, monolithic use of the noun) as they called it.

Counter to the popular belief that American suffrage suffragists called off their suffrage work in order to fully support the war efforts not unlike their British counterparts, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) affirmed their mission in 1917. Carrie Chapman Catt called a meeting of the Executive Council days after Secretary of State Robert Lansing announced that US was breaking diplomatic relations with Germany. The reason for the meeting was to decide is the NAWSA would follow in the footsteps of British suffragettes or if American suffrage supporters will continue to work in support of universal suffrage. The seventy-six members in attendance votes overwhelmingly (63 to 13) to continue to work for universal suffrage while also supporting the federal government if indeed the US went to war against Germany.

Many women did not support Catt’s twin goals, such as pacifists who believed that Catt was selling out the peaceful message inherent to women in order to further the goals of the NAWSA. Others believed that Catt and the NAWSA had not gone far enough, such as Alice Paul.

Alice Paul’s ideas on how to achieve the right to vote diverged from national leaders of the NAWSA such as Catt and Dr. Anna Howard Shaw or regional leaders such as Emma Smith Devoe. Catt, Shaw, DeVoe, and others asked for the right to vote. They were non-partisan. They used “womanly” tactics such as deferring, being demure, and dressing in the latest fashions. The womanly tactics served DeVoe well when she successfully facilitated full suffrage for women of Washington. Paul, on the other hand, demanded the right to vote, blamed those in power (the Democrats during the war) for preventing women to realize the right to vote, and embraced what were considered “militant” tactics. Paul’s militancy included loud protests, interrupting speeches of politicians, unfurling banners questioning political leaders’ judgments, chaining her to fences, allowing her to be arrested, and going on a hunger strike.

Paul even created and co-led (with Lucy Burns) her own suffrage organization called the National Woman’s Party (NWP). Her target was Wilson and to a lesser extent Catt. “We want to convict Wilson of evading us,” Paul wrote to Burns and Paul questioned Catt’s nonpartisanship. Paul also laid the blame of a lack of equal political rights at the feet of the Democrats in general and thus against Wilson in particular. Paul’s first attempt to win the right to vote was under the banner of the Congressional Union (CU). The CU believed the best way to obtain the right to vote was through a Constitutional Amendment. Three years later, Catt announced her “Winning Strategy” which included support of a Constitutional amendment.

The suffrage bill was not moving through the Legislative Branch as quickly as Paul had wished and thus to bring attention to this fact she led a small march/protest of a few dozen members of the NWP. The event took place at Lafayette Square, directly across from the White House on August 13, 1918. This was not the first time that the NWP marched in front of the White House nor was it the first time that the women were attacked by police. Earlier, plainclothes policemen (reportedly members of the Secret Service) broke up a NWP demonstration in front of the Russian embassy and tore up their banners and posters, some of which called into question Wilson’s support for democracy by referring to him as “Kaiser Wilson.” Paul and many others will be arrested.

Paul and other NWP members will be repeatedly arrested as the war waged on, and at the August 1918 protest, police were so violent that they broke fingers and wrists on some of the women. Thirty-eight were arrested. They were booked and released, then they went back to Lafayette Square and resumed their protest, thus they were arrested again. “We will continue to protest as long as our disenfranchisement exists,” proclaimed Paul. “Oppression and abuse at the hands of the law merely emphasized the great need of women for political power.” Refusing to eat, forced to sleep on concrete floors, urinate and defecate in communal pots, housed along side black women, and jailed along side prostitutes carrying syphilis, many of these middle class white reformers were shocked, as too as the American public who were served story after story in New York and Washington area newspapers.

Paul would be arrested in October and sentenced to seven months in jail. She would even be sent to a psychiatric hospital to determine if her actions were the result of some mental or organic disorder. Although she would be found sane, in November another group of NWP protestors joined Paul in prison. The sadistic superintendent, Alexander Whitaker, had the women thrown down stairs, threatened with sexual abuse, and had the women moved from cell to cell by being dragged by their hair. Dorothy Day was beaten by a group of guards. Alice Consu, who suffered a concussion by the hands of the guards, spent her first night in prison vomiting. The next Paul et al began a hunger strike. The superintendent responded by having the women tied down and forced fed by inserting tubes down their throats. Paul referred to these tactics as “administrative terrorism.” Letters and telegrams poured into the offices of Congressmen, Senators, and of course the Oval Office. Newspapers carried daily stories and Alice Paul’s sister, Helen, freely gave interviews in which she questions Wilson’s patriotism and humanity. After weeks of constant pressure, Wilson pardoned all the women and ordered their immediate release. Wilson was still unprepared to support suffrage however. His December message to Congress omitted any reference to the issue, later claiming that his messages to Congress were focused on war matters, not social matters. Yet shortly after the state of New York voted in support of suffrage, Wilson began pressuring members of Congress to vote in support of the federal amendment. The vote could not have been any closer: 274 to 136, the precise number of votes required to continue the process. Wilson, meanwhile, refused to publicly support the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment until the fall of 1918 when he connected suffrage at home with his desire to make the world safe for democracy as evidenced in his Fourteen Points Address of January 1918. “If we reject measures like this,” Wilson said of woman suffrage, the world will no longer believe in the civilizing mission of the United States. However, Wilson ultimately couched his support for granting women equal political status as a reward for their war work.

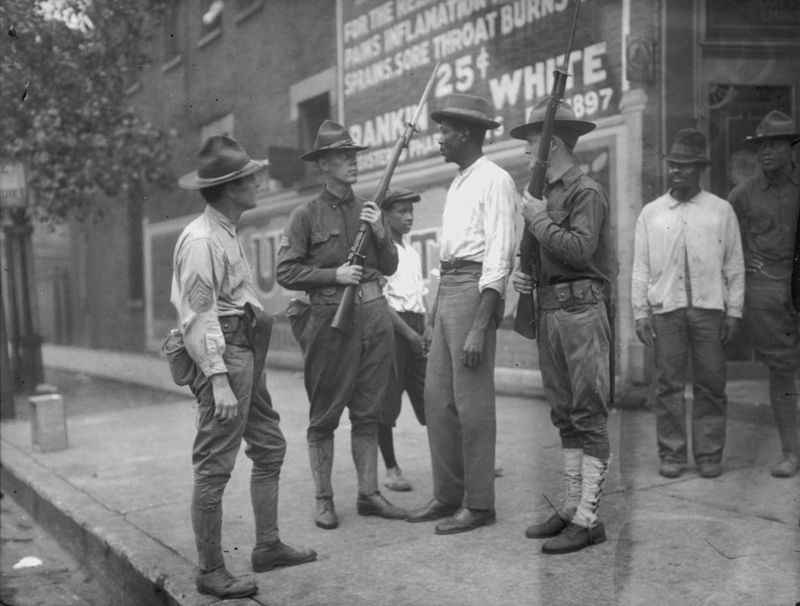

Wrath of God – Black Scare, Red Scare, Influenza

With the fighting in Europe and over the League of Nations behind them, Americans went back to old fashion fighting: against other races and against foreign ideas. As the African-Americans who served this nation during the Great War returned home, some believed that they would be treated as equal members of American society now that they finally proved their worth on the battle field. Others returned home and demanded that the US treat them as equal citizens after experiencing no racism from their French hosts. Simultaneously, white troops returning home noticed the increase in blacks among what were predominately white northern cities such as New York, Detroit, Cleveland, and Chicago. The unemployment rate rose, many black factory workers did not want to give up their new jobs and many white military veterans demanded that blacks be fired in order to give the whites their jobs back.

Armed black and white men attacked each other. Throughout the country massive race riots exploded in the summer of 1919. In Chicago white gangs attacked black neighborhoods. The National Guard eventually ended the attacks and counter attacks that resulted in the death of at least 38 people, nearly 500 wounded, and the destruction of hundreds of homes and businesses. A similar even unfolded in the nation’s capital, resulting in nearly 200 casualties.

What made the riots in Washington, DC particularly disturbing was that many white US military personal, freshly back from defending the liberty of England and France, turned against their own countrymen, women, and children. A few years later, whites in Tulsa attempted to remove all blacks from their town. The NAACP investigated the incident and reported that the prime reason why whites attacked blacks was because of the fear of “radicalism” among black residents. When questioned closely, the NAACP discovered that by “radical” white citizens of Tulsa meant that black citizens were refusing to follow the Jim Crow era codification of racism and “were asking that the Federal constitutional guaranties of “‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’ be given regardless of color.”

Race riots happened throughout the country. The most egregious may have been in Rosewood, Florida. The African American town of Rosewood, Florida was wiped off the face of the Earth and its residents chased away.

Although race riots will decline as the 1920s ramble on, lynchings will increase to include lynchings of blacks in northern towns such in Duluth, Minnesota when three black men will be lynched on suspicion of rape: Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie. Ray Stannard Baker, a reporter, author, biographer of Wilson as well as Wilson’s press secretary at the Versailles peace conference and once said that “Every argument on lynching in the South gets back sooner or later to the question of rape.”[2] Even outside of the South, whites justified rape on the suspected grounds that the lynched person had raped or tried to rape and that the victim was a white woman.

Walter White, a writer and the Executive Secretary of the NAACP published an article in The Crisis in which he outlined the reasons for these race riots, to include the attitudes of African-American veterans:

“These men, with their new outlook on life, injected the same spirit of independence into their companions, a thing that is true of many other sections of America. One of the greatest surprises to many of those who came down to ‘clean out the niggers’ is that these same ‘niggers’ fought back. Colored men saw their own kind being killed, heard of many more and believed that their lives and liberty were at stake. In such a spirit most of the fighting was done.”[3]

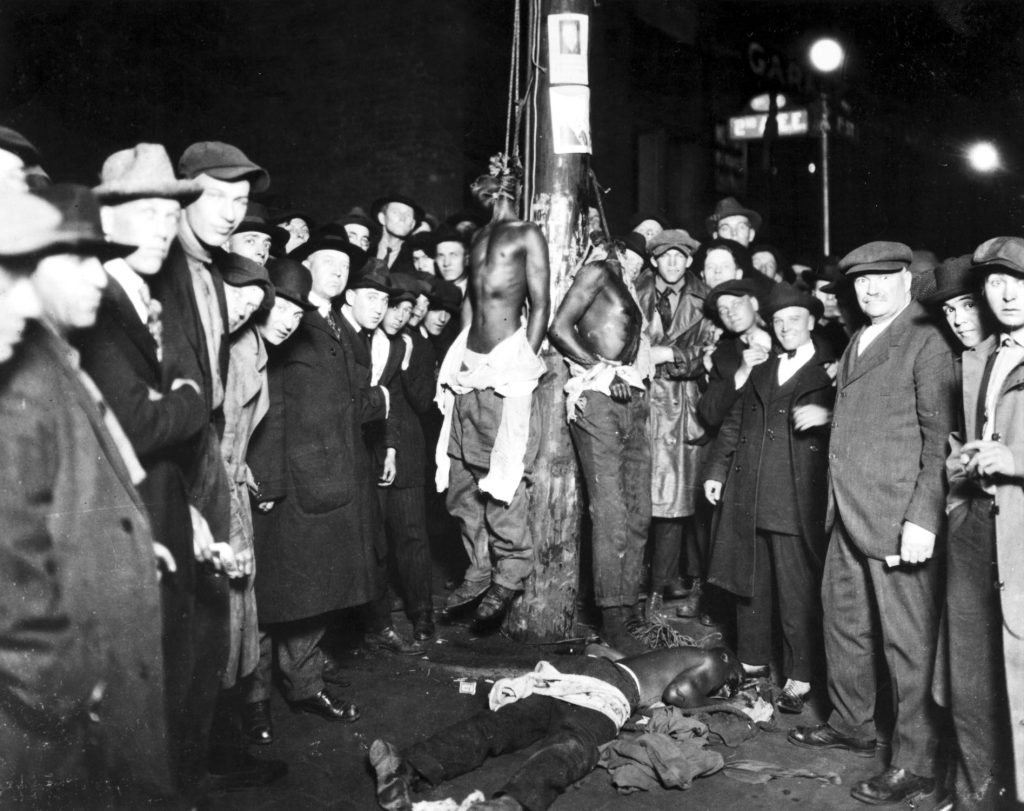

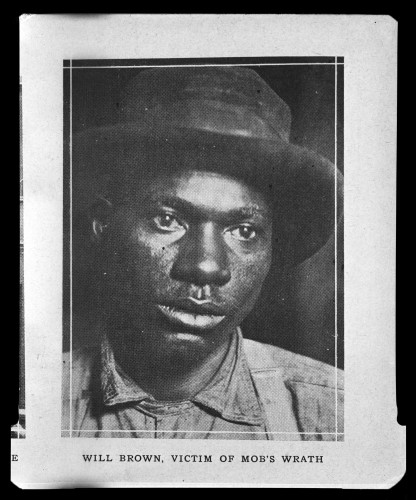

In Omaha, Nebraska, Agnes Loeback alleged that Will Brown robbed and raped her. Brown was arrested. Outside the police station/courthouse a mob grew. Dozens then hundreds then thousands. The governor went to the courthouse to try to get the mob to disperse and the mob almost lynched the governor. Eventually the mob set the courthouse on fire, took Will Brown out into the streets where he was shot dozens of times, then lynched, then set on fire:

“Until the killing of black men, black mothers’ sons, becomes as important to the rest of the country as the killing of a white mother’s sons, we who believe in freedom cannot rest.” –Ella Baker, Civil Rights leader

Racial tension, violence, and death during the “Black Scare” of the 1920s are but precursors to the racial tension, violence, and death that will characterize the civil rights movement following World War II and culminating with forced busing of the 1970s.

Simultaneously, Americans attacked (real and imagined) Socialists, Communists, and those who sympathized with Socialists or Communists. Sometimes those attacked fought back. Unions, union activists, and eastern Europeans in general (especially Poles and Germans) had been intimately linked with Socialism and Communism ever since the Haymarket Square incident in 1886. Unions had typically been viewed in this country as un-American because of the collective nature of unionism seemed to counter the individualistic nature of the United States.

In February of 1919, labor leaders throughout Seattle worked together to hold a city-wide strike. This “general strike,” as they called it, was in protest to a lack of raises. Part of the War Industrial Board’s role during the war was to work with labor organizations to keep the salaries low in order for businesses to make more war-related stuff. Workers were told they were being patriotic by participating in these war time wage controls. Many workers believed, and some were even led to believe, that once the war was over then wages would naturally rise.

Shipyard workers were refused a pay raise in 1919 and thus the Metal Trades Council union alliance declared a strike and closed the yards. Most of the city’s unions voted to strike in support of the shipyard workers. Seattle shut down as more and more businesses were unable to operate (a port town relies heavily on the use of its ports). By February 11th, the strike had ended as a result of pressure labor leaders felt from the stationing of thousands of federal troops, state police, and armed volunteers throughout the city. Most workers had returned to their jobs (expect those from the shipyards who originated the strike) yet local police decided to use the general strike as a justification for attacking a pro-communist union, the International Workers of the World as well as the headquarters of the Socialist Party in Seattle. The strike was a failure for the unions because neither public opinion, nor local media, politicians, even the leaders of the University of Washington supported their tactics of trying to shut down the city. Although the general strike in Seattle ended without almost no violence, a “Red Scare” swept across the United States.

Strikes happened in nearly every major city and local politicians reacted with the use of violence. The American Legion, an organization founded by military veterans in 1919, reported that it had evidence that communists were to lead a revolution following May Day parades (the first of May was a European day of celebrating workers although in the US anarchists, socialists, and communists used “May Day” to remember the Haymarket Square incident).

“Reds Planning to Overthrow U.S. on May Day” American newspapers warned in April on 1919. Package bombs addressed to prominent Americans were discovered in various US post offices and Boston newspapers informed the public of a “Bolshevik plot” to over throw this country under the banner headline “REDS PLAN MAY DAY MURDERS”.

The federal government responded to this (real or imagined) fear of a communist takeover by expelling suspected “alien radicals” such as Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman, and more than 500 others. Many states, such as California, adopted loyalty oaths in which you had to pledge to protect the state and the federal government if you wished to secure certain state jobs. Many of those arrested were denied bail, denied trial by jury, and in some cases there was no evidence against them except the word of the arresting authority. In reaction to this attack on Americans’ civil rights (especially the First, Fifth, and Fourteenth amendments), progressive reformers such as Helen Gurley Flynn helped create the American Civil Liberties Union.

In June of 1919, several bombs went off nearly at the same time throughout the Northeast and in Washington, DC. One in particular was set off in a carriage parked outside the home of the US Attorney General, A. Mitchell Palmer. At this time President Wilson was still recovering from his latest stroke and thus Palmer, working on his own, created a new national intelligence unit called the General Intelligence Division (GID) and hired a young attorney named J. Edgar Hoover to lead the GID. During the summer and fall of 1919, and using the broad powers of the Alien and Espionage Acts, Palmer ordered a series of attacks against suspected internal enemies. Known as the “Palmer Raids,” thousands of suspected radicals were arrested and held without bail.

One possible reaction to these raids was a massive bombing of Wall Street. On September 16th, 1920, a horse-drawn carriage parked near the entrance of the J.P. Morgan bank. Nearly forty people were killed and 400 were injured. “The horrible slaughter and maiming of men and women,” wrote the New York Call, “was a calamity that almost stills the beating of the heart of the people.” “There was no objective except general terrorism,” wrote the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “The bomb was not directed against any particular person or property. It was directed against a public, anyone who happened to be near or any property in the neighborhood.” The Washington Post labeled it an “act of war.” This 1920 attack will be the worst act of terrorism witnessed in New York for another 81 years.

Even elected officials were not safe during this “Red Scare.” Sam DeWitt was elected to the New York state assembly was expelled because he was a Socialist. The voters of Wisconsin elected Victor Berger to represent them in Washington, DC on the Socialist ticket. Berger was refused admittance into Congress and he was expelled from the national capital. The Washington Post applauded the Senate’s decision calling it an “impressive demonstration of Americanism.” Berger will be re-elected but will still be barred from taking his seat Washington, DC.

The political fear of the “Red Scare” following World War II is but a small example of the aligning of the political universe following World War II when the bipolar world of the Cold War will be the driving characteristic of the second half of the twentieth century.

But when I mentioned the flu, I said — actually, I asked the various doctors. I said, “Is this just like flu?” Because people die from the flu. -Donald Trump, Feb. 26, 2020 discussing the coronavirus (COVID-19)[4]

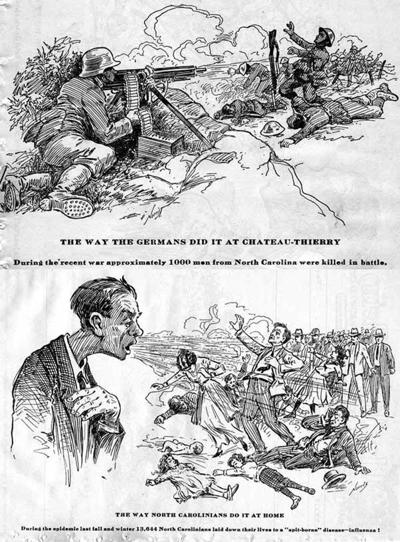

Soldiers returning from western Europe will bring back stories, medals, souvenirs, and influenza, which Americans will call the Spanish Flu in large measure because Spain will be the place where most Americans soldiers were kept before returning to the US. The disease inflected approximately 28% of the US population. Public events were cancelled, such as the Macy’s Thanksgiving parade. Congress appropriated $1 million to establish a new medical research facility that’s called today the Center for Disease Control.

Worldwide deaths averaged 30 million people, or, ten times as many people died from the 1918 influenza pandemic (which probably was born in the trenches and incubated in the overcrowded port towns of Spain while troops waited for ships to take them back home) than from fighting in the trenches during the Great War. 1918 saw the end of the Great War and before the first anniversary of the Armistice, 675,000 Americans will die from influenza.

Conclusion

The “War to End all War”, the “War to Make the World Safe for Democracy”, the “Great War”, and eventually “World War I” were all phrases used to describe the hostilities that erupted throughout Europe and the Middle East between 1914 and 1918. When the war came to an end tends of millions of people were dead, Germany was an occupied nation, American troops were still fighting in Russia (the White Army -about 4500 US Marines-invaded and fought in Russia from 1918 to 1920) and National Guardsmen had been deployed around this country in wake of the racial and political violence. Americans rejected being a player on the international stage, influenza ravaged the world, and American literature and art seemed to reflect this era of death and misery. The KKK reformed, this time out of Indiana. And, the Chicago White Sox threw the 1919 World Series.

The Versailles meeting among American, Italian, French, and British leaders certainly did not settle any of the big questions that Wilson posed in his January 1918 address. Most of the colonial holdings of the Ottoman Empire, Austria, and Germany were redistributed among Great Britain, France, and Italy. One group of people known as the Kurds desperately clung to Wilson’s idea on “self determination.” They tried to carve a country for themselves out of the remnants of the Ottoman Empire and the Persian Empire. They called their country Kurdistan and the League of Nations turned to the United States to tutor the country’s political, economic, and social leaders. The US refused and Kurdistan was consumed among Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria, not unlike how the world was consumed by the flu. Since the Great War, the Kurds have been but the fuzzy, yellow tennis ball being smacked around in a game in geo-political mixed doubles among the governments of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. We are still dealing with the Kurdish question today.

Palestine was a backwater province of the Ottoman Empire yet Palestinians sought independence and they were not willing to change one master (Istanbul) for another (England). A young Arab military leader named Faisal traveled to Versailles in the hopes of being able to convince the Allies to allow Palestine to become an independent country. The allies refused, Palestine was taken by England. We are still dealing with the question of Palestine today both in terms of billions of US dollars each year, the cost of the Israeli occupation, and in the loss of lives.

A young Vietnam nationalist leader named Ho Chi Minh traveled to Versailles in the hopes of meeting with President Wilson. Minh wanted the help of the US to transform his country from a colonial holding of France into an independent nation based on the political and economic example of the United States. Wilson refused to help and ultimately over one million American troops will be sent to fight against Ho Chi Minh’s forces resulting in the over 60,000 American deaths and nearly 400,000 wounded Americans.

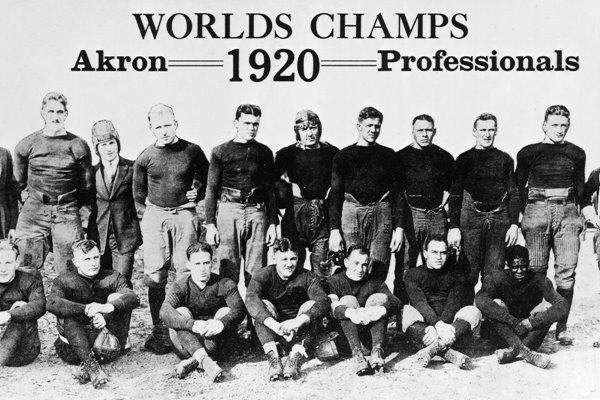

The Akron Professionals were the champs of the inaugural year of the American Professional Football Association (the forerunner to the NFL).

Initially, the NFL had African America players. Not until the 1930s would that change. Example of an African American football players who experienced success in APFA and later in the NFL were Frederick “Fritz” Douglass Pollard and Robert Marshall.

“Frederick Douglass Pollard was one of the first African American players to play professional football and also the first to become a head coach.”[5] Pollard’s pro football career began in 1919 when he became a member of the Ohio’s Akron Pros. Pollard was a victim of racism just like in high school from players that did not want him on the field. He played quarterback for the NFL. Later in 1921 he became the co-head coach of the Akron Pros still keeping his spot as a player. “After that he became the head coach Milwaukee Badgers, Hammond Pros, Providence Steam Roller, and his most famous and successful team The Harlem, New York-based brown bombers.”[6] That was until the “gentleman’s agreement” in 1933 when the NFL enacted the segregation of the league.

Robert Marshall known as Bobby Marshall was also one the first two African American to play for the NFL. “Marshall entered the University of Minnesota to play position of end. Making tying touchdown against their rivals University of Michigan in 1903. Also, he helped his team beat the University of Chicago. Later he was the first one African American to play for the Big Nine Conference.”[7] Marshall then played for the National Football League from 1920-1924. Both Marshall and Pollard helped them Pros win the championship in the NFL inaugural season.

In 1933-1945 the NFL banned African Americans from playing with the league. It was not until 1946 the NFL re-admitted the African Americans into the world of professional football and made an immediate impact. “The Los Angeles Rams became the first NFL team to integrate when they drafted Kenny Washington.”[8] Where he played for only 3 seasons and retired in 1948.[9]

Right around the corner is the “Roaring 20’s”. Just how can such a depressed and dejected nation seemingly bounce back into a decade of dancing, music, and never-ending celebration? They don’t. Just like the “War to End all War” failed in its titular objective, the Roaring 20’s were certainly not roaring for those in the center of the decade-long social, political, and economic hurricane as you will see.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies therefore, please point them out to me so that I may make this chapter better. Also, I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- October 11, 2017 in a tweet. https://www.cnn.com/2017/10/11/politics/donald-trump-media-tweet/index.html ↵

- http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/active_learning/explorations/lynching/baker2.cfm Last accessed 20 FEB 20. ↵

- African Americans in the Jazz Age: A Decade of Struggle and Promise, p. 108, by Mark Robert Schneider. ↵

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-vice-president-pence-members-coronavirus-task-force-press-conference/ ↵

- http://www.nfl.com/news/story/0ap2000000325958/article/fritz-pollard-a-forgotten-trailblazer ↵

- https://theundefeated.com/features/fritz-pollard-was-a-true-football-pioneer-black-quarterback/ ↵

- http://theweeklychallenger.com/african-american-firsts-in-pro-football-history/ ↵

- https://www.history.com/news/first-black-nfl-player ↵

- Damaris Morin, a student of mine from the Spring of 2020, provided this content. ↵