10 Creating These United States, 1783-1800

1783-1800

Jim Ross-Nazzal, PhD and Students

“What is the most sacred duty and the greatest source of security in our Republic? An inviolable respect for the Constitution and Laws.” -Alexander Hamilton

“”It’s a very rough system. It’s an archaic system, . . . It’s really a bad thing for the country.” -Donald Trump on the constitutional system of checks and balances[1]

The period after the American War for Independence, when the country was under the Articles of Confederation, the failure of that compact, and the rise of the Constitution, is a period of the pulling away from the British colonial roots. An attempt to create an American reality that clearly diverged from their Britishness in politics and society. Many people and events went into creating these United States such as Africans both slave and free.

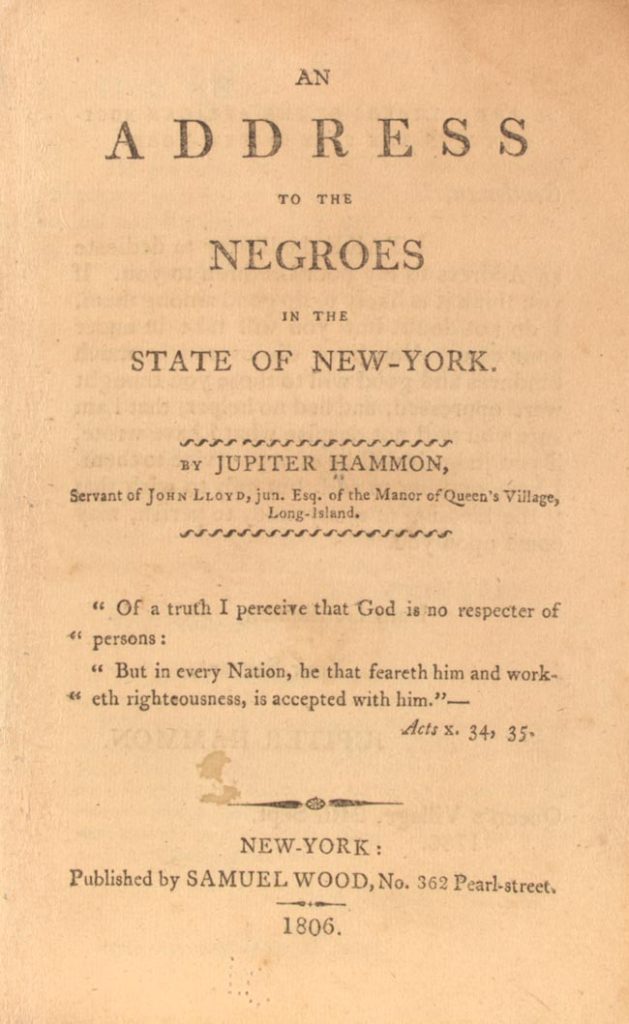

Jupiter Hammon

Jupiter Hammon was a slave from New York. His masters allowed him to learn to read and write and Hammon demonstrated a innate ability at prose. He was a preacher, more of an evangelical who wrote poetry and was a slave. Yet he wrote about the evils of slavery and frequently spoke out against slavery. He remained a slave until his death. Here is an excerpt from one of Hammon’s poems:[2]

An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ, with Penetential Cries

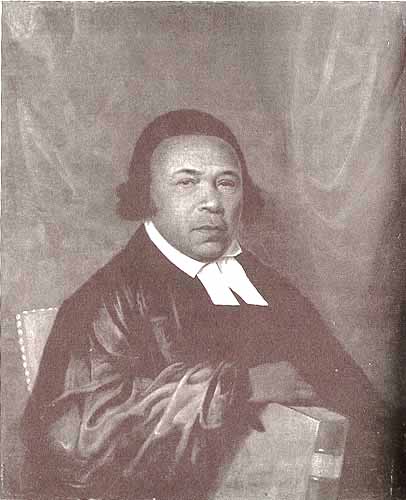

Absalom Jones

Reverend Jones was born into slavery in 1746 but was set free by his master in 1784. He helped establish the Free African Society in Philadelphia, an organization established to help newly freed slaves settle in Philadelphia. There was a religious aspect to the Society as well. During the Second Great Awakening, Jones established the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, the first all black congregation in Philadelphia. In February of 1808, Jones gave a sermon in which he briefly mentioned slavery:

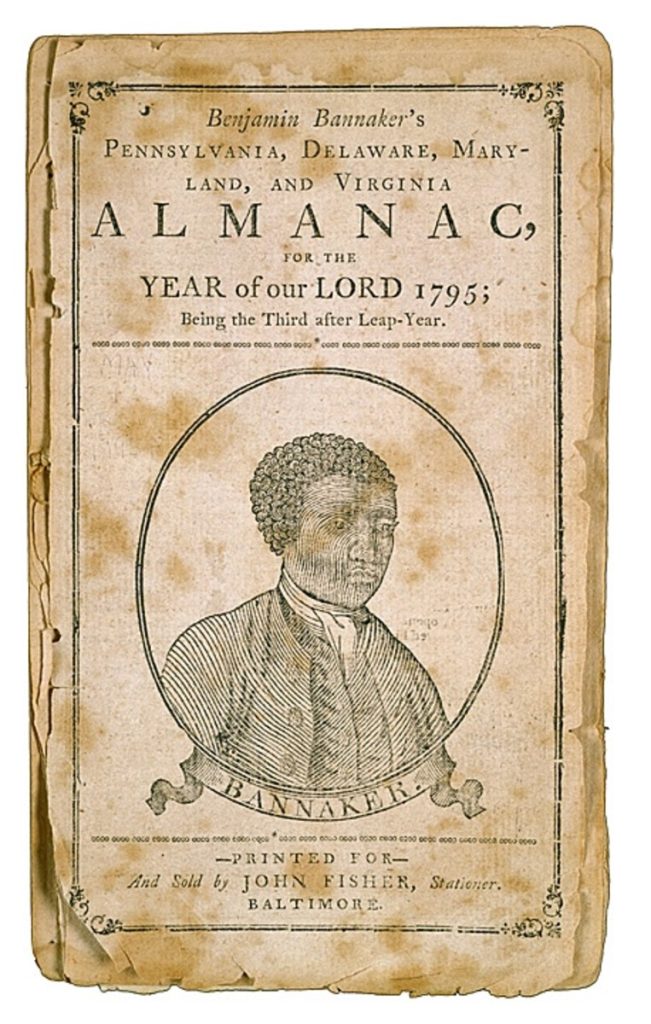

Benjamin Banneker was a free African who was a leading astronomer (published much on astronomy) and mathematician (he would help survey the streets of what became Washington, DC). He corresponded with Thomas Jefferson regarding slavery and abolition. His popularity resulted in much support among white scientists. In a 1795 edition of one of Banneker’s almanacs, a poem was written in his honor and ended with this tribute to his African heritage:

That Afric’s sable race have talents too.

And may thy genius bright its strength retain;

Tho’ nature to decline may still remain;

And may favour us to thy latest years

With thy Ephemeris call’d Banneker’s.

A work which ages yet unborn shall name

And be the monument of lasting fame;

A work which after ages shall adore,

When Banneker, alas! shall be no more![4]

Annapolis Convention

Disputes among the states arose due to a lack of a powerful central government. Each state tried to engage in its own foreign affairs and economic policies that at times ran counter to the goals of other states. More and more states refused to pay taxes to Congress, which only grew the national debt making foreign governments less likely to extend credit to the new nation. States engaged in a trade war with each other leavening tariffs on imported goods and argued over state boundaries. Civil War broke out in Massachusetts (Shay’s Rebellion) and Congress worried about unrest spilling to the other states. So, American leaders called for reform, a change in government, or a change in the relationship between the government and the governed. “It’s time to clip the wings of this mad democracy!” said Henry Knox. George Washington wrote to James Madison “We are fast verging to anarchy and confusion.” Representatives met in Annapolis to discuss issues pertaining to commerce. However, the representatives instead called for a nationwide meeting to be held in Philadelphia to discuss reforming all aspects of the Articles of Confederation. 55 representatives from 12 states (Rhode Island refused to participate) met in Philadelphia in 1787.

There were three intentions of the Convention. First, to protect property rights and to protect the nation from unbridled democracy. Second, the idealistic notion of creating “a more perfect union.” And, a pragmatic approach to dealing with issues of sovereignty and placing common interests over regional interests. Those in attendance were relatively younger than those who wrote the Articles of Confederation. They held professions besides farming and were of relative means. Most were war veterans and some of the traditional elites, such as Thomas Jefferson, boycotted the meeting.

The Constitution

Creation of a central government.

Congress has the right to levy and collect taxes.

Created a federal court system to deal with issues among the states and its citizens.

Created the Executive Branch with a President who selects his Cabinet.

Bicameral legislature with the Senate consisting of two representatives from each state and the House of Representatives based on population.

Provided a way to create and maintain an army.

Control interstate commerce.

The Fifth Amendment tothe US Constitution will be of particular importance to this period in US History. Article I of the Constitution gives the power to legislate for the territories to Congress. But the Fifth Amendment states that people cannot lose their life, liberty or (here’s the big one) property without due process. So what would happen if Congress established a free territory while pro-slavery folks use the Fifth Amendment to argue that Article I of the Constitution is unconstitutional? Both the power to restrict slavery in the territories and the ability not to lose your slaves without due process cannot exist in the same reality. Abraham Lincoln and the leader of the traitors, Jeff Davis, will both argue, initially, that the Civil War was not about slavery but about power. Did the federal government trump the states (Article 1) or do the states trump the federal government (Fifth Amendment)? Vamos a ver.

Ratification

Only 9 out of 13 states were needed to ratify the new agreement. Out of fear of state legislators (who were in the hands of those who supported radical democracy), conventions elected by the people were given authority to accept or reject the Constitution. Those who supported the creation of a strong central government and thus the Constitution were known as Federalists while those opposed were known as Anti-Federalists. Most Federalists were wealthy, educated, and enjoyed economic, political, or social status during the late colonial era while most Anti-Federalists were farmers who supported state governments over a federal government. The latter feared the taxation power of a federal government and worried that any federal government could rule such a large nation. The promise of an enumerated list of rights swayed many Anti-Federalists to support ratification. George Mason was put in charge of coming up with a list of specific rights. Mason’s list consisted of 200 rights, which would be whittled down to 12 in 1789, of which 10 would be ratified in 1791. Although James Madison believed that rights needed to be spelled out, he also supported the establishment of a strong, powerful, central government: “A spirit of locality was destroying the aggregate interests of the community.” And although Madison described slavery as a great evil, he also believed that “a dismemberment of the union would be worse” thus he ignored calls from some to support the abolition of slavery in the Constitution.

The Federalist Era

There were two competing ideas: those of Hamilton and his supporters and those of Jefferson and the Jeffersonians. Alexander Hamilton believed that people were inherently self-centered, egotistic, and would be what is their best interest at the expense of the community. He believed that the “unthinking many” must be controlled by something stronger (a federal government) in order to protect the rights of everyone. A philosophy popularized by Thomas Hobbs. Thomas Jefferson believed that government got in the way of people experiencing their liberties and freedoms. That people know what is best for them and if allowed to do so people, at the most common level, would create government that best mirror the community’s interests and needs. An idea put forth by John Locke. Both Hobbs and Locke witnessed the English Civil War and both had divergent ideas for how the Civil War came to be. One blamed the “unthinking many” while the other blamed an overreaching federal government.

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton was George Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury. As such he forwarded an economic plan based squarely on his convictions that the federal government was supreme. He called for protective tariffs to stimulate the national economy, that the federal government should assume the debts of the states, and create a national bank as a repository of national assets and to issue paper money based on those assets. A tax that Hamilton supported was a fee on whiskey. The tax was somewhat burdensome on western farmers who relied on the production and sale of alcohol to augment their household incomes. Whiskey producers in western Pennsylvania revolted against the government. The Whiskey Rebellion was to the Constitution as Shay’s Rebellion was to the Articles of Confederation. While the latter proved the ineffectiveness of the Articles of Confederation, the former proved the solvency of the Constitution. George Washington personally led the efforts that put down the revolt.

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson opposed Hamilton’s vision. First, Jefferson believed that government could only do what the Constitution specifically stated government could do, known as the strict constructionist view. For example, the creation of a national bank went beyond Congress’ authority as the Constitution did not call for the establishment of a national bank. Second, Jefferson believed this country’s future lay out west and that the West would be populated by yeoman farmers, independent from each other and government. People who would grow their own food. Make their own stuff. And what they could not grow and could not make they would do without. While Hamilton envisioned this country’s future in cities and an economy that was based on industry, not agriculture.

Furthermore, the French revolution further divided the Hamiltonians and the Jeffersonians with the former calling for a strong government to protect property rights and the latter supporting the idea that people can make their own governments (and remove those governments if need be). George Washington declared that the US would remain neutral (in large measure because choosing sides would cut off half of US trading partners). The idea of neutral rights was a corner stone of US foreign policy through World War I.

Foreign Entanglements

Two major treaties came about during the presidency of Washington. First, Jay’s Treaty (1794) resulted in England promising to abandon their forts in the American frontier and to stop seizing US ships traveling to France or French ports. Then in 1795, Pickney’s Treaty provided the US with unfettered navigation along the Mississippi River. However, the treaty did not allow US access to the Mississippi through the port of New Orleans. Thomas Jefferson will address that issue when he becomes president. A foreign affairs crisis erupted over the treatment of US officials in France. French authorities demanded that the US pay a bribe before France would negotiate treaties with the US so President John Adams launched a brief series of naval strikes against French ships called the Quasi War. The war came to end in 1800 with France capitulating to the American’s’ demands of free trade.

The Federalists got into hot water during the Quasi War then Congress passed two bills that extended the reach of the central government. The Alien Act, among other things, allowed the federal government to imprison aliens during a time of war and allowed the president to deport aliens without court proceedings. And the Sedition Act prohibited any speech that was deemed negative towards and by the federal government. A clear attack on the First Amendment. The first victim of any US war is the First Amendment. Luckily, that Amendment is resilient. Anti-Federalists and those in opposition to the extension of the federal government’s powers loudly protested in the streets and in the press. Jefferson and Madison, for example, authored the Kentucky and Virginia resolves, which stated that the states had the right to disobey Congress if laws enacted exceeded Constitutional authority. Intellectually, that was the first step towards the session crisis on the eve of the Civil War. The election of 1800 ended the reign of the Federalists with anti-Federalists, or Jeffersonians, or Democrats, controlling the Executive branch through the presidency of Andrew Jackson.

Speaking of elections and foreign entanglements, on December 6th, 1787 John Adams wrote to Thomas Jefferson about his concerns regarding foreign intervention in American elections.[5]. On December 18th, 2019 the House of Representatives impeached Donald Trump for his attempts to persuade a foreign power (Ukraine) to influence the 2020 presidential election and found Donald Trump a threat to national security.

Republican Motherhood

The press exploded after the War. almanacs, gazettes, Bibles, political memoirs, novels, and biographies such as Life of Washington by Mason Weems. Most of the fiction we grew up believing about Washington was created by Weems such as the cherry tree story. Even contemporaries of Weems panned the book as patently fiction. And more books and magazines were being published for and about women while girls began attending what they called “common schools.” Literacy rates rose. Charlotte Temple, by Susanna Rowson, was a novel about “a schoolgirl, Charlotte Temple, who is seduced by a British officer and brought to America, where she is abandoned, pregnant, sick and in poverty.” The book was in print for a century.[6]. Judith Sargent Murray published “On the Equality of the Sexes.” In the essay, Murrray lays forth her argument that woman are the religious and intellectual equals of men. Here is an excerpt:

“But our judgment is not so strong—we do not distinguish so well.”—Yet it may be questioned, from what doth this superiority, in this determining faculty of the soul, proceed. May we not trace its source in the difference of education, and continued advantages? Will it be said that the judgment of a male of two years old, is more sage than that of a female’s of the same age? I believe the reverse is generally observed to be true. But from that period what partiality! how is the one exalted, and the other depressed, by the contrary modes of education which are adopted! the one is taught to aspire, and the other is early confined and limitted. As their years increase, the sister must be wholly domesticated, while the brother is led by the hand through all the flowery paths of science. Grant that their minds are by nature equal, yet who shall wonder at the apparent superiority, if indeed custom becomes second nature; nay if it taketh place of nature, and that it doth the experience of each day will evince. At length arrived at womanhood, the uncultivated fair one feels a void, which the employments allotted her are by no means capable of filling. What can she do? to books she may not apply; or if she doth, to those only of the novel kind, lest she merit the appellation of a learned lady; and what ideas have been affixed to this term, the observation of many can testify. Fashion, scandal, and sometimes what is still more reprehensible, are then called in to her relief; and who can say to what lengths the liberties she takes may proceed. Meantimes she herself is most unhappy; she feels the want of a cultivated mind. Is she single, she in vain seeks to fill up time from sexual employments or amusements. Is she united to a person whose soul nature made equal to her own, education hath set him so far above her, that in those entertainments which are productive of such rational felicity, she is not qualified to accompany him.[7]

What did it mean to be an American? For many Americans that simply meant not being British. Culture, as believed, was transmitted from mother to children and thus arose in the early United States the definition of an American woman, called Republican Motherhood. Women existed to have children and to raise those children to be patriotic. Mothers would educate their children about American history, government, art, geography, and music. Young boys would grow up to serve the state and young girls would grow up to have the next generation of patriotic Americans. Therefore, American women needed to be educated. They needed to be literate so they could read books on American history and society in order to best train their children to understand and relish Americanism. Women’s participation both on the battlefield and back at home as the sole household providers during the Revolution spurred this new idea, which resulted in an expansion of liberties for women. These ideals (ideals) will be formulated and expressed by, in part, Dr. Benjamin Rush, a professor of Chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania. Rush was also an signatory of the Declaration of Independence. In his work “Thoughts Upon Female Education.” Women, he wrote, “must be stewards and guardians of their husbands’ property” thus women needed to be educated in such aspects as accounting and property rights. In addition, women needed good penmanship, an understanding on how geography affected the establishment of the US, knowledge of and ability to sing American songs, play musical instruments, how to dance the popular dances, history, travelogues, poetry and “moral essays” in addition to teachings of Christianity.[8]

Republican Motherhood came about due to the American War for Independence. The War propelled women to take over farms and businesses while their husbands or fathers went off to war. And, so many women demonstrated their capability in handling their new found roles as farmers and shopkeepers. Women participated in the Continental Army. Most as camp followers but even some as soldiers who experienced combat. And although men did not line up after the War to pledge their support for a change in the roles or position of women following the war (normally women were escorted back into their kitchens following these national emergencies), women sensed and began calling for a change. There were some men who believed it was time to reevaluate women’s roles in American society, such as Dr. Benjamin Rush.

So the value of motherhood became esteemed as the foundling nation discovered its cultural identity would be transmuted through mothers. This new “American” culture include four characteristics: rationality, patriotism, honor and civic duty. And although not permitted to have a direct role in politics, women were considered to have an indirect role through having an influence over their husbands’ political decisions and through their sons’ political choices through their education.[9]

Again, Dr. Rush outlined the specific type of education American women would first have to received if they were to properly bestow American culture upon their own children. Such education included writing “of a fair and legible hand,” bookkeeping, geography, history, biography, and travel literature in order in part “to be an agreeable companion for a sensible man.” Women would be taught to sing and dance and all these and other types of education would be wrapped up “with regular instruction in the christian religion.”[10]

Judith Sargent Murray

Lakecea Saffold found out a few things about Murray’s early years:[11]

Murray began writing in her adolescence. She was around nine years old when she began to write.[12] However, at that age she was just a babe in her writing adventure. The poems that she wrote during her early years were mere steppingstones that would lead up to a platform of literary mountains. As she grew older, she wrote under many pseudonyms. She wrote as a male in the Massachusetts Magazine as “The Gleaner”, where she discussed many issues that would lead to fearful times for her family.[13] Her family had to move to another city which led her to become a seed sower in the field of woman’s equality.

Murray was most passionate about the limited opportunities for a good education for women. She argued, “The female brain was inherently inferior, that women were not stifled by physical limitations but by the lack of access to education”.[14] Her writing pursued to persuade Americans that women were not indeed inferior, they were just not provided with the needed tools to prove that they deserved equality in a society where only what the male sex did mattered. Her passion for better education for women earned her a spot in what they would later coin the women advocates of this time as Republican Motherhood.

Judith Sargent Murray (1751-1820) was not viewed as a woman who displayed republican values because she spoke in favor of gender equality while Republican Motherhood necessarily concluded that women had specific roles to play in American society that were subservient to their husbands’ or fathers’ roles. Her second husband, John Murray, introduced Universalism to the United States. Universalism promoted numerous progressive tenets, such as the education of women, which in and of itself was a republican ideal. Judith Sargent Murray spent her life promoting women’s education. She wrote a regular column for the Massachusetts Magazine. Her topics covered all the great topics of the day from foreign affairs to recipes. She is probably best known for her essay “On the Equality of the Sexes” where she advocated equal educational opportunities for women. Opponents used their Christian bibles to denounce her ideas both on equality and on female education, starting with Eve’s “sin.”

Here is an excerpt from the appendix of On the Equality of the Sexes:

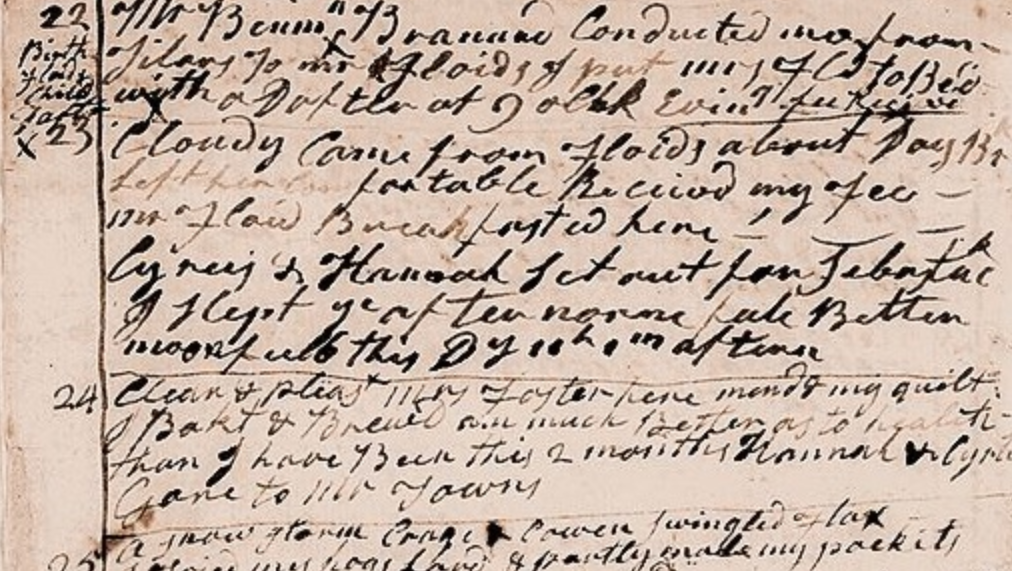

Martha Ballard

The ideal American women was quite different than the reality for American women presented by Dr. Rush. One example was Martha Ballard. Ballard was the first in her home to rise each morning. She would make breakfast then assign chores to her adult children who still lived at home. Then she paddled her canoe up and down what is today the Kennebunkport River attending to the needs of primarily women. She was a midwife. She delivered babies, created medicine, and attended to bruised and broken limbs of those farmers. She was paid in what was most needed: food. Chickens, eggs, meat, etc. She kept a diary of her life and so Ballard’s firsthand experience is vital to our understanding of the trials and tribulations of American women at this time in American history.

The type of education called for by Dr. Rush reached very few women of Ballard’s time. “Very few women of Martha Ballard’s generation left behind writing in any form. [Her] grandmother was able to muster a clear but labored signature on the one surviving document that bears her name, but [Martha Ballard’s] mother signed [her name] with a mark. However there were many highly educated men in her family to include her paternal uncle, a college-graduated physician, two brothers-in-law who were physicians, Jonathan Moore (her brother) was a librarian at Harvard who then became a Congregational minister. “Most New England girls were taught to read at least enough to understand the Bible. But writing skills were not essential for a girl’s education. However [Martha Ballard’s] ability to write cursive . . . tells us that someone in Oxford, Massachusetts in the 1740’s was interested in educating girls.[16] That would be decades before the rise of Republican Motherhood.

Here is what Dr. John Lienhard of the University of Houston had to say about Martha Ballard:

In 1777, 42-year-old Martha Ballard and her husband, Ephraim, moved to the town — if you could call it that — of Hollowell, Maine. Hollowell’s 100 log cabins were strung out along the wide, flat Kennebec River — an Atlantic seaport, 46 miles inland.

Ephraim was a 4th-generation millwright. Martha was literate but not educated. Her spelling was — well — highly creative. She’d mothered eight children, with one more to come. Three had died in a diphtheria epidemic eight years before. Now Martha, after a lengthy apprenticeship, took up midwifing in Hollowell. In 1785, she also began a diary, which she kept until she died in 1812.

The diary somehow survived, and what a window on early American life it gives us! 814 recorded births by 1812 and maybe 200 before she began writing. Her working conditions were appalling — crossing the Kennebec on breaking ice in the spring — death and incurable illness riding on everyone’s back — pulling flax when she wasn’t pulling babies. Here’s a typical entry:

Snow hail & rain. I left [Mr. Parker’s] lady at 4 pm as well as Could be Expected & walkt over the river. Wrode Mr. Ballard’s hors home. I had a wrestless night from fataug & weting my feet.

Her performance was astonishing. In over one thousand births she lost only five mothers and twenty babies. A mother was in far better hands with Martha Ballard than she would’ve been in a London hospital. Modern American deliveries weren’t any safer than hers until WW-II.

Of course her midwifing was just about all the medicine the good people of Hollowell had access to. So her diary also provides an 18th-century pharmacopoeia. Her biographer, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, lists her nostrums in her own words. For example:

Eunice had a very severe pain in her teeth & face. I aplyd some scorcht Tow & hett her face & and she got Ease, . . .

Or:

[Summer savory] expels tough phlegm from the chest and lungs.

Or:

Elisa very unwel. We aplyed Turnip poltis to her bowels which gave relief soon.

She didn’t mention abortion, though births out of wedlock were fairly common. By the time she died, patent medicines were on the market with the cloaked suggestion that they could aid a woman’s health but were dangerous if she was pregnant.

By then, commercial medicine, city medicine, and male medicine were all reaching Hollowell. The world was changing. So much that was good about Ballard would now be replaced, along with her obvious limitations.

Yet if you want to learn how America was really formed, then read Martha Ballard’s laconic diary — A Midwife’s Tale. For it is in the detail of a hard life, well lived, that civilization is made.[17]

Ulrich, L.T., A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990.

While the lofty goals of Republican Motherhood were experienced by women from the most wealthy of families, general ideas on female education, patriotic duties, and relative parity in the household did trickle down to the general population. Republican Motherhood would expand women’s liberties and roles in American society, albeit temporarily due to, in large measure, a reaction against the new roles for women in the Second Great Awakening.

An Nguyen examined Republican Motherhood.[18]

Republican Motherhood was a long-term history event where people had struggled fighting for influence of women in politics of American republic. In this chapter of Moral, Manners, and the Republican Mother, Rosemarie Zagarri demonstrated excitingly how this event was developed. “Originally articulated by contemporaries such as Benjamin Rush and Judith Sargent Republican motherhood affirmed that women had a profound influence on the political values of the American Republic.”[19] It was an important event because it gave women opportunities to be educated, which was not an option for women at that time.

The story of Zagarri began with Linda Kerber’s examination, which provided a negative conclusion that Western political had only considered women’s main role is in domestic relationship.[20] It was Linda Kerber’s book, Woman of the Republic, who sparked an explosion on finding woman’s role in politic. The women’s role in American politics was based partly on group of Scottish theorists: “the civil jurisprudential school.” It had many ideas that featured woman’s role in society. First, it stated “Yet the family remined the basis for the entire social structure.”[21] They also confirmed the important of “Manners”. Mothers are always an important part of family, and they straightly shape their family’s manner. By these ideas, they implied that women, especially mothers, had indirectly improved, even orientated to society. On the other hand, they used “the four-stage theory of history.”[22] In this theme, they experienced four stages: hunter, shepherd, farmer and merchant. As more civilized the stage was, as more influence women were. They confirmed that “in order for women to fulfill new role as men’s friend and companions, they would need to be educated.”[23] It is where women in Scottish get opportunities to go to school, to reach to education. However, both Scottish’s themes didn’t solve effectively the problem of women’s role in politic.

The four-stage theory was well-known in American. Many books were published. “In 1768, James Wilson and William White published a series of sixteen essays in the Pennsylvania Chronicle”. “In 1792, Thomas Odiorne published a work called The Progress of Refinement, A Poem in Three Books”. It became a hot topic that time. It was well-known by both women and men, by both the elite class and a middle-class. It was most important in American Republican that they had found women’s role in politic, especially in republic. “In a republic, the women must raise the future generations of male citizens and must support their husbands in the sacrifices they made for the government.”[24] Though a long-term of researching and developing, combining from both tradition and innovation, the most valuable insight was created. It is Anglo-American Womanhood. “It acknowledged the importance of female education, but generally saw its function in terms of women’s relationship to men.”[25]

The role of women in American politic now has changed significantly. They influence in politic greatly now, as a successful result of Republican Motherhood. Asian countries, where women’s role in politic is limited, reflect effectively why Republican Motherhood is so important. In China, “a woman has never been selected for the Standing Committee of the Politburo, the top governing body. Since 2013 two women have occupied seats in the 25-member Politburo, the first time since the early 1970s.”[26] These countries have not much participation of women in political work. Also, it partly limits women in getting chances of education. “While East Asia, with China at the centre, may be on the rise, it still lags behind in terms of women’s rights and political representation.”[27]

In conclusion, Republican Motherhood was an important event fighting for women’s role in politic and education for women in not only America, but also in many Western countries. What it had achieved in the past is now, still a challenge for many other countries in the world, especially those developing countries that women didn’t have any chance in politic.

Second Great Awakening

Another wave of religious revivalism had its roots in the 1790s. Hallmarks of this Great Awakening include the massive conversion of Africans, slave and free, to Christianity, women preachers, and the rise of more American religions that are still with us today such as Mormonism and the Seventh Day Adventists, as well as and new ways of ordering society. And there will be a push back from the established religious elite, resulting in a new, much more restrictive role for American women called the Cult of True Womanhood or the Cult of Domesticity. I will cover those events in the next chapter. That’s called a tease.

I’d like to thank my students Lakecea Saffold and An Nguyen for her dedication to women’s history.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies. Please point them out to me so that I may make make this chapter better. I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- https://www.salon.com/2017/05/01/donald-trump-doesnt-like-the-archaic-constitution-its-really-a-bad-thing-for-the-country/ ↵

- https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/52545/an-evening-thought-salvation-by-christ-with-penetential-cries ↵

- http://anglicanhistory.org/usa/ajones/thanksgiving1808.html ↵

- https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112037299119&view=1up&seq=57 ↵

- https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-12-02-0405 ↵

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Temple ↵

- http://www.digital.library.upenn.edu/women/murray/equality/equality.html ↵

- https://books.google.com/books?id=ibUicWY4SlIC&pg=PA76&lpg=PA76&dq=Rush+must+be+stewards+and+guardians+of+their+husbands+property&source=bl&ots=jaF3MfHu08&sig=ACfU3U0PbMJhpDf_R12PT08ZpLT7QbkYdg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjnvrSMofvkAhVLMawKHeV0D-0Q6AEwAnoECAcQAQ#v=onepage&q=Rush%20must%20be%20stewards%20and%20guardians%20of%20their%20husbands%20property&f=false ↵

- Originally attributed to www.geocities.com/jigmaster007/unit2/question15.html Last viewed 30 Sep 2002 ↵

- "Thoughts Upon Female Education Addressed to the Visitors of the Young Ladies' Academy in Philadelphia, 28 July 1787, By Benjamin Rush, M.D." ↵

- Ms. Saffold was one of my students in the Fall of 2019. ↵

- Michals Debra PhD. “Judith Sargent Murray”. National Women’s History Museum. 2015. Accessed 15 Oct. 19. womenshistory.org. ↵

- Murray Sargent Judith. “On the Equality of the Sexes”. National Humanities Center. Accessed 15 Oct. 2019. nationalhumanitiescenter.org/sargent.pdf ↵

- Michals Debra PhD. “Judith Sargent Murray”. National Women’s History Museum. 2015. Accessed 15 Oct. 19. womenshistory.org ↵

- http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/livingrev/equality/text5/sargent.pdf ↵

- http://dohistory.org/diary/about.html ↵

- https://www.uh.edu/engines/epi1035.htm ↵

- Ms. Nguyen was a student of mine in US History, Fall of 2019. ↵

- Republican Motherhood, “Moral, Manners, and the Republican Mother” by Rosemarie Zagarri, page 192 ↵

- Ibid. 193. ↵

- Ibid. 196. ↵

- Zagarri noted that “it was first suggested by Montesquieu in his Spirit of Laws, published in 1748”. ↵

- Rosemarie Zagarri, “Moral, Manners and the Republican Mother”, page 200 ↵

- Ibid. 206. ↵

- Ibid. 210. ↵

- Katharine H.S. Moon, Wellesley College, “Women and Politics in East Asia”, 19 June 2016 ↵

- Ibid. ↵